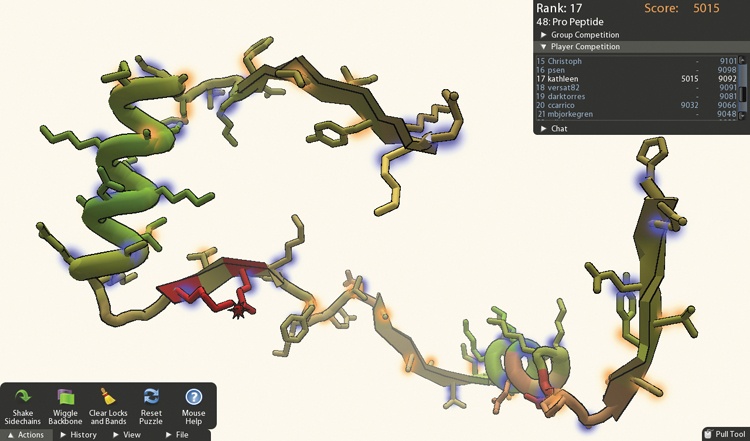

This puzzle is killing me. I’ve looked at the chain from 20 different angles, and I just can’t see the solution. I decide to take a stab in the dark and twist one of the blue pieces inward. It costs me 300 points. Crap. Then it hits me: if I bend the whole chain into thirds, all of the orange pieces will be on the inside, just where they’re supposed to be. That does the trick. I finish the puzzle and I’m off to the next level.

I’m playing Foldit on my home computer. Its look and feel is as familiar as that of any video game (that is, any game mediated by a computer), with its bloops and bleeps and multicolored flying sparkles. But the puzzle itself is actually modeled on an object from nature: a protein chain that must be folded into a particular shape (Figure 1-1). This is a complex challenge in modern biochemistry, and even supercomputers aren’t especially good at finding the solutions. But people’s natural aptitudes for spatial manipulation and creative thinking make them better suited to the task. “Without a human being to help out, a computer just kind of flails about trying to get the pieces to fit together,”[2] explains Seth Cooper, one of the designers of Foldit. He’s part of a team of computer scientists and biochemists at the University of Washington who collaborated to build Foldit as a way to make the task fun, engaging, and accessible to the general public.

You might recall that Foldit hit the news in September 2011 after its research team published the structure of a protein related to the growth of a virus that causes AIDS in monkeys—a solution that had eluded researchers for over a decade.[3] When the problem was put to Foldit players, they solved it in just 10 days. For the most part these are not trained scientists, but people who just play the game because they enjoy the challenge it presents. Given a discovery of sufficient magnitude, it’s conceivable that anyone playing this video game—even with no prior knowledge of biochemistry—could win a Nobel Prize.

As a user experience (UX) designer, I can’t help but think that an example such as this, in which a designer took a problem that we would normally handle through conventional software and instead successfully approached it through a video game, is something really worth our attention.

Today there are many experiences that, like Foldit, reach beyond the traditional role video games have occupied. There are games that serve as social glue between old friends, and games that bring strangers together to collaborate. There are games that help people meet their life objectives, and games that let people reward others for meeting theirs. There are games that facilitate creative self-expression, that help people understand the news, that train doctors to save lives, that advocate for human rights, and that work to engage people in politics. I would say that designers are pushing the boundaries of what it means to be a game, except that few boundaries now seem to exist.

Video game design and UX design share some common traits, and as games spread out into new realms where they create real benefits for individuals, families, schools, governments, businesses, and societies, the distinction between our disciplines will become fuzzier and less important. This is a great thing, because it exposes a space into which UX design can expand and gain access to entirely new ways of enabling more compelling, inventive, and enjoyable experiences. In this book I advocate that, as designers of conventional software and Web user experiences, we should incorporate video game design into our tool kit and learn how to appropriately apply game solutions to real problems of design. As I’ll show, we have everything to gain.

There is a strong cultural bias that games must necessarily be frivolous. When people say that something is “just a game,” they mean it would be a mistake to take it seriously. When they warn that something is “not a game,” they mean it should be treated with the proper gravity. So why should UX professionals, who design serious applications, take games seriously?

In fact, there are tangible reasons why it would be a serious mistake not to.

Above all things, games must be enjoyable. But that shouldn’t be taken to mean that they must necessarily serve frivolous ends. The fact that many familiar video games are pure entertainment is a matter of convention, not of necessity.

It’s not hard to find games that have effects in the real world. Gambling is one example. Most people would accept that poker, blackjack, and craps fit conventional definitions of games. Modern slot machines are, in every way, video games. But these games also have real impacts on players. They can be ruinous to those who develop compulsive gambling habits, and when that happens, to say “It’s just a game” has no real meaning.

Conversely, games can be directed toward positive ends. For example, there’s a rapidly growing sector of video games designed to improve people’s health. Exergames like Wii Fit and Just Dance build physical activity right into the gameplay and have proven to be massively popular among players. The annual Games for Health conference is dedicated to exploring ways that games can be used in physical therapy, health education, and disease management. Other designers have used video games to encourage charitable giving, build communities, increase awareness of social issues, educate students, and increase the fuel efficiency of cars. (I’ll return to each of these later in the book.)

This is the single greatest reason why we should care about video games: they have the capacity to solve real problems in the real world. Moreover, given the right circumstances (discussed in Chapter 2), they can do so more effectively than nongame user interfaces applied to the same problems. The cultural bias that games are necessarily frivolous only holds us back from exploiting a deep mode of interactivity. To take greatest advantage of the capabilities that game design can bring to our tool kit, we need to throw that prejudice into the trash.

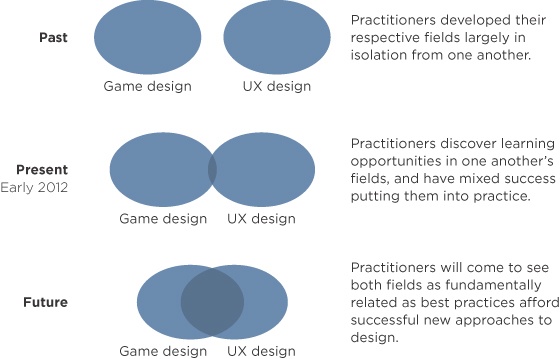

User experience design and video game design are something like siblings who were raised in separate homes. It’s easy to understand both as forms of human-computer interaction and as centrally concerned with the design of experience. But UX design creates experiences that help people meet their real-world needs, whereas game design is about the experience for the sake of the experience.

Although related, these disciplines diverged in the 1960s and ’70s when some software developers chose to pursue productivity applications and others chose to produce entertainment. Both camps grew into massive industries, developing their own methods, best practices, design patterns, gurus, and killer apps. Since we matured largely in professional isolation, today there is a great opportunity for us to learn from one another. Both UX designers and game designers can benefit from discovering the solutions that each has independently developed for similar problems. In the near future, I have every expectation that these disciplines will continue to merge, overlap, and become harder to delineate (Figure 1-2).

Popularity may be a crude measure of merit, but the pronounced success of the video game industry makes it impossible to ignore. The numbers speak to a cultural change under way, where gaming is becoming a part of everyday life.

Consumers are collectively spending huge amounts of money on video games, which are emerging as both an important sector of the global economy and a dominant form of recreation.

The video game industry saw total worldwide revenue of $24 billion in 2010.[4] More Americans now play video games (63 percent) than go out to the movies (53 percent).[5] People’s habits are shifting away from traditional media, with video games occupying a larger proportion of our downtime.

In November 2011, Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 3 took in more than $775 million worldwide in five days, making it the highest-grossing launch of any form of entertainment in history.[6] The title was actually just the latest in a succession of games to have claimed the same record, and video games now appear unbeatable by other media in terms of pure sales.

Guinness lists Microsoft’s Kinect controller for the Xbox as the fastest-selling consumer electronics device in history, with 8 million units sold in its first 60 days on the market.[7]

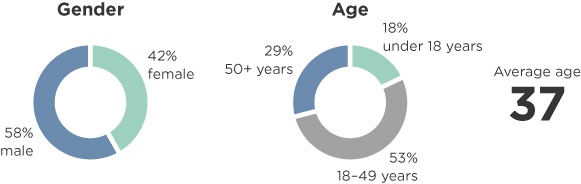

Video games were once very much a niche entertainment, played mostly by young boys on home consoles. That’s no longer the case. The video game industry has grown by branching out aggressively into other demographics, publishing titles with wide-ranging appeal and putting them on systems that are easier to use (and often already in your pocket). Today, video games are enjoyed by a very diverse set of consumers, and there is no longer a single profile for the typical game player (Figure 1-3).

Figure 1-3. Demographic profiles of US video game players as of 2011, according to survey data from the Entertainment Software Association.

Of all US video game players, 58 percent are male and 42 percent are female. Women 18 and older now actually represent a larger segment of all video game players than do boys 17 and younger.[8]

The average age of US video game players is 37. One reason for that relatively high number is that people who grew up playing video games never really stopped. Fifty-three percent of all players are between 18 and 49 years old, and 29 percent are over 50.[9]

Social games like FarmVille in particular have found a home among more mature people and among women. A 2010 survey found that 93 percent of social game players in the United States and the United Kingdom are over 21, with an average age of 43; and 55 percent are female.[10]

I could go on. But the real significance of these numbers lies in the effect that video games, with this level of popularity, are having on culture and society.

Particularly significant for UX designers, video games are becoming a normal way of interacting with machines. On average, people who play games in the United States spend 13 hours per week with them, and in extreme (but not uncommon) cases, more than 40 hours per week.[11] A 2008 survey found that fully 97 percent of American kids between the ages of 12 and 17 played video games.[12] Among younger age groups, gaming is a ubiquitous activity that will inevitably influence the way they think about interactive experiences. Those of us who work in the UX field want to leverage the conventions with which people have grown most familiar. UX designers need to understand games out of necessity, just to stay current.

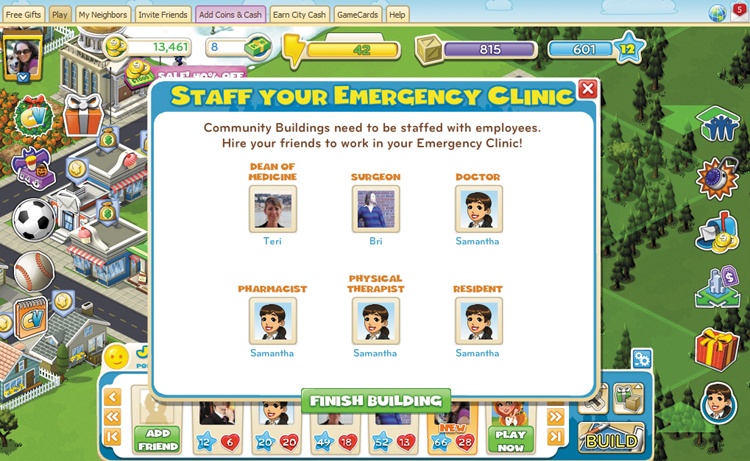

Video games are also building and shaping social relationships among people. For example, World of Warcraft allows players to form guilds with one another to pool resources and take on challenges collectively. Guilds facilitate a social experience that has resulted in friendships, rivalries, and even marriages among people who have no connection outside of the game universe.[13] Other games, such as CityVille, are created expressly to serve social ends, and they give players little choice but to involve as many friends as possible in the game experience in order to advance (Figure 1-4).

Figure 1-4. CityVille promotes a social experience by giving advantages to players who work together to progress in the game.

All of these games comprise entirely new ways for people to relate to one another through a shared experience in a separate universe driven by communal goals. As video games continue to gain in popularity and the generation growing up inside these virtual environments matures, we can be sure that the implications for society as a whole will be far-reaching—even if it’s not yet entirely clear what they will be.

As an inevitable consequence of their popularity, video games are gaining a new cultural legitimacy that’s elevating them to a central place in our shared consciousness. Emerging from a cultural backwater, video games have entered the mainstream in a big way.

Game design has built up a sea of creative thinking that runs both deep and wide. The fierce competition among modern game companies has forced them to innovate, and one way they try to differentiate themselves from one another is through interface design. Increasingly, game makers are experimenting with technologies like motion control, gestural interfaces, and linked displays (I discuss these in greater depth in Chapter 14). These will drive the development of inexpensive, high-quality consumer products that can be repurposed for applications well beyond gaming. If we’re not paying attention to games, then we’re missing out on some of the most exciting innovations in UX design.

The modern sophistication of computers and consumer electronics owes a lot to video games, which created a demand for devices that had faster processors, richer graphical displays, sophisticated sound, and intuitive means of input.[14] Games also predispose people to user interfaces that make the interaction feel like play. It’s easy to forget how much fun the original Macintosh was to use in 1984, but that was a big factor in its appeal. Today we get that same toylike feeling when we pick up an iPad.

I believe that UX designers’ core competencies predispose us to acquiring the methods and practices that lead to the design of high-quality player experiences. Even better, we can bring a unique perspective to game design that can give rise to fresh approaches. In particular, certain specific attributes of the UX community suit effective game design.

We’ve got experience in experience. Our practice is built entirely around elevating the user’s qualitative experience of a design. User-centered design is closely related to the player-centric thinking that’s common to all good game experiences.

Games are moving toward our areas of expertise. For those of us who have worked in the development of online systems (especially social and mobile applications), game design has arrived in our backyard. The collision between games and the Internet has opened new creative avenues for designers. Our aptitudes in these realms can bring new thinking to game design, just as demand is ramping up.

We know how to work the technology. We design experiences using software technology as our raw material. Video games arise from many of the same root technologies that we use to design software, and they’re often played on the same devices. The skills we’ve developed working on these platforms translate well to games.

We’re in touch with real-world problems. Businesses and public and private agencies are increasingly putting up funds for games that solve real-world problems. People working in the game design industry tend to be more focused on creating unique intellectual properties in service of pure consumer models, leaving a gap that creates a demand for skilled designers. With our established backgrounds developing products for diverse clients and projects, UX designers are well positioned to fill that gap.

I want to be careful to say that I’m not suggesting the UX design community is presently ready to just sit down and start making games. Game design is a robust and cerebral practice in its own right, and much of it turns our usual ways of thinking upside down. Operating successfully in the games domain means learning an entirely new set of competencies and gaining experience putting them into practice. This book is intended to get you started down that road.

Let’s suppose we accept that video games are important and that UX designers should be paying attention to them. How, then, do we actually make use of any new knowledge or skills we gain from deepening our understanding of game design? I can think of three ways that we can incorporate game design into our work.

Call this the direct method. Some everyday tasks can be redefined to be experienced as games. Users become players, following the rules and seeking the objectives set by the designers, and the game in and of itself is their motivation to engage in the experience. Many applications naturally lend themselves to such treatment, as I’ll discuss in Chapter 2.

This approach resembles a current fad that some people call “gamification.” I’m not a fan of the term, because it implies that the designed product remains fundamentally an application that just happens to have some game elements tacked on. Such an approach can lead to half measures that are transparently dressed up to obscure the application at its root. Instead, I’m talking about reconceiving applications first and foremost as true games that are enjoyed for their game-ness, but that also happen to have effects in the real world.

This approach requires a conceptual leap on our part to picture how everyday activities could succeed as games. Part III of this book explores some ways that inventive people have accomplished this.

Of course, not everything can be redefined as a game. Trying to force a game structure onto an application that’s just not suited to it won’t work, and I wouldn’t argue that you should try. But with the conventions of games becoming a familiar way for people to interact with machines, you can instead realize tremendous benefit from incorporating conventions and design patterns that are familiar to people from their interactions with games.

One of the most dramatic examples of this indirect approach is Second Life, which is at its heart a communications system akin to a chat room that lacks the objective-driven play of a true game. But Second Life adopts the convention of physical presence in games to transform the experience into something much richer (Figure 1-5).

Figure 1-5. Second Life is not a game, but it builds a rich interactive experience by adopting the conventions of games.

However, not all indirect approaches need to adopt a game skin so thoroughly. Just being tuned in to the ways that games operate can inspire new insights and creative solutions to everyday problems of design.

One last way that we could use games is as games. In other words, there’s no need to import them into the UX world in order to get something of value from them, because games themselves are valuable experiences. When we sit down to play a video game, we fully engage our consciousness to surmount a difficult challenge. We learn and acquire new skills at a fast pace. We apply strategic thinking, exercise creativity, and seek out the most efficient solutions to problems. We develop and deepen relationships with other people taking part in the play. We enjoy ourselves and then reflect fondly on the experience when it’s over.

Why shouldn’t these things, in and of themselves, be enough? If our central concern is the quality of an interactive experience, then there’s no reason why video games, which can satisfy people so richly, should be excluded. Interactions with software or websites can often be aimless and arbitrary anyway, without the clearly defined objectives we like to assume in their design. When no such goals exist, people can find much more meaning in solving a puzzle, outfoxing a friend, or building a virtual home. Our ability to deliver these experiences to people can only deepen the relevance of our field.

Video games present great new opportunities to UX designers, the limits of which are set only by the extent of our own imagination and creativity. At the same time, when we create a game we must take on a new set of responsibilities to our users (who we would need to get used to calling “players”) to support experiences that engage, excite, and entertain. Games have an obligation to their players’ sense of active enjoyment that goes beyond what UX designers normally need to deliver. That’s also precisely the thing that makes game design so interesting. Creating a new class of playful designs that can make life more captivating while also making it more successful is an opportunity that we should savor.

So let’s go. This is going to be fun.

[2] Phone interview with the author, March 8, 2010.

[3] Khatib, F., DiMaio, F., Foldit Contenders Group, Foldit Void Crushers Group, Cooper, S., Kazmierczyk, M.,... Baker, D. (2011). Crystal structure of a monomeric retroviral protease solved by protein folding game players. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, 18, 1175–1177. Note: This is by far the longest and stodgiest citation in the book. I promise.

[4] NPD Group. (2011, March). Games industry: Total consumer spend (2010). Referenced at www.npd.com/press/releases/press_110113.html.

[5] NPD Group. (2009, May). More Americans play video games than go out to the movies. Retrieved from www.npd.com/wps/portal/npd/us/news/pressreleases/pr_090520.

[6] Activision press release. (2011, November 17). Retrieved from investor.activision.com/releasedetail.cfm?ReleaseID=624766.

[7] Guinness world records 2011: Gamer’s edition. (2011). Brady Games.

[8] Entertainment Software Association. Essential facts about the computer and video game industry: 2011 sales, demographic and usage data. Retrieved from www.theesa.com/facts/pdfs/ESA_EF_2011.pdf.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Information Solutions Group. 2010 social gaming research. Retrieved from www.infosolutionsgroup.com/2010_PopCap_Social_Gaming_Research_Results.pdf.

[11] NPD Group. (2010, May 27). Extreme gamers spend two full days per week playing video games. Retrieved from www.npd.com/wps/portal/npd/us/news/pressreleases/pr_100527b.

[12] Lenhart, A., Kahne, J., Middaugh, E., Macgill, A., Evans, C., & Vitak, J. (2008, September 16). Teens, video games, and civics. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved from www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2008/Teens-Video-Games-and-Civics.aspx.

[13] Rushkoff, D., & Dretzin, R. (Writers); Dretzin, R. (Director). (2010, February 2). Digital nation: Live on the virtual frontier [Television series episode]. In Fanning, D. (Executive producer), Frontline. Arlington, VA: PBS. Retrieved from www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/digitalnation.

[14] Thompson, C. (2010, December 31). The influence of gaming [Radio interview]. In On the Media. New York, NY: WNYC. Retrieved from www.onthemedia.org/2010/dec/31/the-influence-of-gaming.