CHAPTER 4

Planning

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Understand the meaning, significance and characteristics of planning

- Enumerate the types and essentials of effective goals

- Understand the types of planning

- Enumerate the meaning and types of strategy

- Explain the approaches to planning

- Differentiate between strategic, tactical and operational planning

- Elucidate the steps in the planning process

- Understand planning premises

- List the barriers to effective planning

- Enumerate the steps to make planning effective

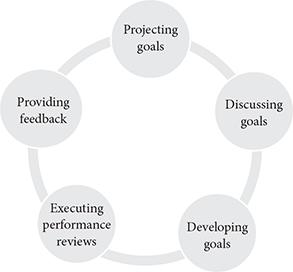

- List the feature and phases of MBO

- Explain the relevance of SWOT analysis

- Understand the steps involved in strategic quality planning

India’s Inspirational Managers

Indra Nooyi is the chairman and chief executive officer of PepsiCo. She became the first female to lead a company that ranked 41st in the Fortune 500 list of companies. She has been successfully directing the company’s global strategies and programmes for more than a decade. She has also designed the major restructuring programmes of the company including its divestiture and acquisition programmes. The crux of her administrative strategy is “adaptability,” “performance with purpose” and “performing while transforming,” especially when undertaking restructuring programmes. She explained performance with purpose as “doing what’s right for business by doing what’s right for people.” Nooyi has specifically focused on the areas of environmental sustainability, talent sustainability and health and wellness. She believes in: (i) scanning with open eyes, (ii) approaching every situation with open ears, (iii) following adaptive leadership, which is to approach things with an open mind and (vi) building an adaptive culture, which means leading with an open heart. Before joining PepsiCo, Nooyi worked for Motorola, where she was the vice president and director of Corporate Strategy and Planning.

Introduction

“Thinking before doing” is an act of planning. In any organization, planning is the first managerial function. Managerial planning helps an organization to decide where it wants to be in the future and how to get there.1 It offers direction to the whole organization and runs through the entire organization. It is a key to the success of other managerial functions, such as organizing, directing and controlling. It enables the organizational members to know clearly what is expected of them. Planning is essentially a complex, comprehensive, and continuous process of an organization. This process involves the identification of goals and determination of actions for accomplishment of those goals.

The planning expects the managers to foresee the future, anticipate the changes and get ready with the action Plans. It is capable of considerably reducing the uncertainties faced by the managers. Further, planning ensures that managers determine their resource requirements accurately, utilize them properly and also minimize the wastages continuously. Planning brings orderliness to the organization as all its activities are coordinated and executed in a predetermined manner. Planning avoids confusions as employees are informed in advance about their goals, roles and responsibilities in the organization.

Definitions of Planning

Preparing an organization to deal with the future events is the focus of many definitions of planning. We shall now see some of the important definitions.

“Planning is the design of desired future and of effective ways of bringing it about.” —Russell L. Ackoff.2

“Planning is a process concerned with defining ends, means and conduct at every level of organizational life.” —Gerald A. Cole.3

“Planning is deciding in advance what to do, how to do, when to do it and who is to do it.” —Koontz and O’Donnell.4

“Planning is the act of determining the organization’s goals and the means for achieving them.” —Richard L. Daft and Dorothy Marcic.5

“Planning is that function of management in which a conscious choice of patterns of influence is determined for decision makers so that many decisions will be coordinated for some period of time and will be directed towards the chosen broad goals.” —Joseph L. Massie.6

“Planning is essentially the analysis and measurement of materials and processes in advance of the event and the perfection of records so that we may know exactly where we are at any given moment.” —L. F. Urwick.7

“Planning means both to assess the future and make provision for it.” —Henri Fayol.8

Besides the above definitions, some other authors have also explained the term, planning. For instance, planning is “fundamentally choosing” for Billy E. Goetz.9 An anonymous expert has described planning “as a trap that is set to capture the future.”

We may define planning as a process of establishing need-driven goals that synchronize the organizational activities and develop ways for accomplishing those goals.

Characteristics of Planning

The following are the characteristics of planning:

- Planning is essentially a continuous activity of the management. Plans may be prepared for specific periods but planning as an activity is performed throughout the life of an organization.

- It is a dynamic function because it should be constantly evaluated and adapted to conform to the new developments in the organizational environment.

- It is all-pervasive in nature as plans are made at all levels of the management. The scope of planning usually covers the whole organization, especially the long-term plans.

- It is a future-oriented action as plans are prepared for the future and not for the present or past.

- It is a choice-based decision-making activity. As a part of planning, several alternative courses of actions are identified and analysed, and then the best alternative is selected.

- It is a goal-driven activity. This is because the goals formulated at the beginning of any planning process determine and direct all other activities necessary for its accomplishment.

- It is basically an intellectual exercise like any other decision-making activity. As a mental exercise, it first involves thinking through all aspects of an issue or a problem. This thinking later forms the basis of all actions.

- It is interventionist in nature in the sense that it tells the employees what should be done, how it should be done and when it should be done.

- Planning is a complex and challenging activity as it involves the selection of the best course of action in an uncertain and complex environment.

- It is a process because it passes through multiple stages like goals definition, policy (guidelines) formulation, resource (physical and human) mobilization, goal fulfilment and reviews.

In brief, plans must necessarily have four basic qualities. They are: (i) quality, (ii) accuracy, (iii) continuity and (iv) flexibility. The presence of these general qualities can get the desired outcome at the end of the planning period.

Significance of Planning

Planning is regarded as one of the most important functions of both small and large organizations.10 It involves the establishment of general guidelines to ensure that all organizational activities are carried out in a predetermined and an orderly manner. Let us now discuss the importance of planning in detail.

- Improved performance—Planning improves the success rate of the organization by constantly focusing on the end results (i.e. goal accomplishment) than on other activities.

- Proactive approach—It promotes a proactive approach by encouraging the organizations to look, plan and act ahead of the competitors in the market. It thus encourages managers to action rather than reaction.11

- Future-focused management—Planning ensures that management allots adequate time and resources for the future activities of the organization. This makes it certain that future risks are anticipated, assessed and minimized by the organization.

- Better coordination—Goals and objectives formulated as a part of plan provide direction to the whole organization. Goals and objectives ensure that there is a proper coordination among all the members and their activities.

- Basis for controlling—Plans predetermine the performance targets for different departments, divisions, units and individuals of the organization. These performance targets act as the standards for comparing the actual performance and also for determining performance efficiency at various levels.

- Enhanced employee communication and involvement—Planning facilitates better administration, as information on plans and goals are shared with the employees. Employees’ feedbacks are also routinely collected about plans. Frequent information exchange as a part of the planning process also improves the employment involvement and morale.

- Objectivity in decision making—The most effective way to ensure objectivity in decision making is to plan in advance the short- and long-term goals to be achieved. Planning ensures that the organization has adequate time to consider all options in detail before a final decision is arrived at.

- Cost-effectiveness—Planning ensures that the organizational resources are effectively mobilized and properly utilized. It also facilitates the managers to decide how and when they allocate the physical, financial and human resources. It thus makes sure that resource wastages are kept to the minimum.

- Legitimacy—Planning involves the framing of mission and vision goals for the organization. Mission and vision goals of an organization stand for the reason for the existence of the organization. They symbolize legitimacy to the stakeholders like investors, customers, suppliers and distributors, besides the local community.12

However, it should be noted that only effective plans can yield the desired results for organizations. To be effective, plans must be clear (easy to read and understand), concise (short and to the point), credible (accurate and believable), logical (arranged in an orderly pattern) and persuasive (convincing and motivating and results in goal accomplishment).13

Orientations to Planning

According to Ackoff,14 organizations can adopt any one of the four orientations to planning based on their own beliefs and philosophy. The four orientations to planning are: (i) reactivism, (ii) inactivism, (iii) preactivism and (iv) interactivism. Let us now discuss them briefly.

- Reactivism—Managers view the past as the best period and aim at returning the organization to its previous state. Such organizations normally adopt paternalistic hierarchy in planning and also look to preserve the traditions and ensure continuity. They attach great importance to tactical planning—a short-term operational planning. However, technologically-advanced organizations eventually replace those organizations that adopt reactive planning.

- Inactivism—Managers look to avoid changes and maintain status quo. In case of crisis, the intention of planning is limited to just reducing the discomfort and not tackling its root cause. These organizations normally adopt a bureaucratic approach to planning. Inactivist managers normally give higher emphasis for tactical and operational plans (discussed later in this chapter).

- Preactivism—Managers with preactive orientation to planning look to exploit the future opportunities by accelerating the change process. They aim at mastering technologies that are responsible for changes. Preactive organizations normally adopt management by objectives, inventiveness, decentralization, informality and permissiveness to planning.15 Preactivist managers often provide more importance to long-term planning.

- Interactivism—Managers firmly believe that the creation of a desirable future is possible. They meticulously design and develop ways and means to realize this belief. Interactivist organizations consider technology, experience and experiments as pivotal as they facilitate development, learning and adaptation. Interactivists usually place greater importance on normative planning.

Goals—An Overview

Planning will be an useless exercise for any organization, if it does not have well-defined and realistic goals. The goals guide the actions of the planner from the beginning till the end. Goals are the foundations of all planning activities. In the beginning, it provides direction to the planning exercise and, in the end, it controls the process by facilitating the measurement of the efficiency of the plan. Goals are thus critical to the organizational and planning effectiveness. Organizations can have different kinds of goals for serving different purposes, but all these goals must be aligned properly. Effective organizational goals would have hierarchical alignment. In other words, achievement of goals at lower levels leads to the achievement of goals at higher levels. This is called means–end chain.16

Though goals can be known by different names, such as mission, objectives, road maps, etc., they have a few common benefits. They are as follows:

- Goals offer guidance and unified direction to the organizational members.

- Goals keep the employees focused on their activities as they are aware of the expected outcome of their actions in a stable environment.

- Goals and plans are capable of effectively complementing one another. An effective goal setting facilitates sound planning which, in turn, brightens the chances of developing superior goals in future.17

- Goals that are transparent and rewarding can be a valuable source of motivation for employees. They can also keep the employee morale high since they may find their jobs challenging and result-oriented.

- Goals are effective instruments for performance evaluation and control. Goals become the standards for comparing the actual performance of employees and also for determining the efficiency level.

Kinds of Goals

Goals are the predetermined results organizations seek to achieve through their planned actions. However, organizations may call goals by different names, depending on their scope, purpose, duration, etc. Let us now look at the important forms of goals.

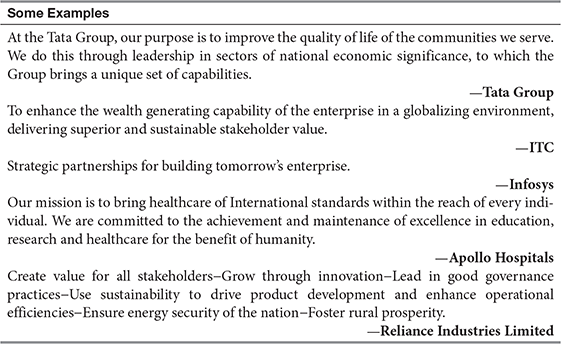

Missions—These are the official goals that describe an organization’s reason for existence. A mission statement provides a separate identity to each organization. It also sets organization’s business apart from its competitors and others. A mission statement normally contains information regarding: (i) the purpose of an organization’s existence, (ii) intended beneficiaries (customers, public, employees, etc.) and (iii) the likely impact of its existence. A mission statement offers broad guidelines to the managers when they determine priorities, make decisions and allocate resources.

Mission statements also form the basis for finalizing the objectives and goals of the organization. They also act as communication tools of the organizations. They officially and authoritatively communicate the values, beliefs and motives of the organization to the stakeholders. A mission statement is also the formal expression of an organization’s vision (statement of the organization’s future ambitions), values, belief and attitudes. It also provides legitimacy to the existence of an organization and improves its image in the eyes of the public. The mission statements of some leading organizations are presented in Table 4.1.

Objectives—The terms objectives and goals are often used interchangeably in management. However, there are subtle differences existing between objectives and goals. Time span and specificity are the two factors that distinguish objectives from goals.18 Objectives are specific and short-term targets to be achieved before the goals can be reached. Objectives are statements of specific and short-term nature that lead to the accomplishment of more general and long-term goals. Box 4.1 shows the objectives of SAIL.

Table 4.1 Mission Statements of Organizations

Box 4.1

Objectives/Strategies of Steel Authority of India Limited (SAIL)

The current strategies of SAIL expressed in the form of objectives are:

- To continue to be mainly in the business of Steel and Steel-related activities.

- To protect market share and grow by focusing on increasing share in growth segments.

- To aim at achieving international/national benchmarks on product cost and consumption ratios, especially in the new units with due allowance for prevailing conditions, technology, facilities, inputs, etc.

- To aim at excellence in quality across the value chain.

- To build customer-centric processes, systems, structure and procedures.

- To maintain financial health with rational investment and controlled borrowing.

- To carry out interventions to achieve all-round functional improvements in marketing, human resources, infrastructure and utilities, maintenance, information technology, environment and safety management, etc.

- To remain a socially responsible company by committing certain amount of profit towards society in the areas of peripheral development, education, health, sports, family welfare, etc.63

According to Donna Hardina, “Objectives are steps to reaching the goal and must be related to specific task or process. They must also be time-limited and measurable. For instance, the annual objectives of organizations play an important role in the accomplishment of their strategic goals.”19 Well-defined and well-designed objectives are accurately measurable and are linked to the organization’s long-term goals. According to James Stoner, “Annual objectives identify clearly what must be accomplished each year in order to achieve an organization’s strategic goals.”20

Objectives of organizations can broadly be classified into task objectives and process objectives. Task objectives concentrate on the completion of specific tasks (like production of a specific quantity of a particular brand) within a predetermined period. Process objectives focus on the means that are necessary for the completion of the task-related activity. For instance, process objectives may aim at recruiting and training the skilled persons to accomplish the task objectives. It is to be noted here that some management authors differ with the view that fulfilment of objectives are the means to realizing the goals of organizations. According to them,21 goals are specific and short-term exercises, whereas the objectives are used to indicate the end point of a management programme.

Goals—In simple terms, goals are the desired outcomes or targets of organizations.22 Goals are the broad and long-term targets of an organization. Managers must ensure that the goals are based on the idea of choice and clarity.23 Goals are usually considered as multidimensional since the number of objectives is incorporated into an overall goal. It is important for the managers to ensure that their goals are effective enough to guide the activities of their organization. In this regard, they must ensure the following:

- Goals should be specific and cover the key areas of results. Managers must not formulate goals for each and every activity or behaviour of the employees.

- Goals should define the period of time, from its formulation to achievement. It must specifically state the date of commencement and completion of the goals.

- Goals must be formulated on the principles of choice and clarity. Clear, direct and carefully-chosen goals can ensure optimum utilization of organizational resources.

- Goals must be realistic and attainable. If goals are too difficult to be achieved, they may cause frustration and disquiet among the employees.

- Goals must always be a fruitful exercise for the participants. Reward-based goals can get better cooperation and involvement of employees.

- Goals must be measurable in nature. Quantifiable goals can act as effective standards for measuring the performance of employees. Goals are thus meaningful when they are specific and measurable.

- Goals must be explicit and transparent. Written goals must be widely communicated to all its participants in order to ensure their effective participation.

Organizational goals can be classified as financial goals and strategic goals. Financial goals pertain to the financial performance of an organization. Strategic goals are linked to all other aspects of an organizational performance. For instance, fixation of profit target is a financial plan while determination of the number of units to be produced can be a strategic plan.

Goals can also be classified as stated goals and real goals. Stated goals are the official statements meant primarily for its stakeholders such as investors, customers and general public. Annual reports and other public statements of organizations usually have information about these goals. In turn, real goals are those goals (actions) that organizations actually follow. These goals may or may not be in conformity with the stated goals. Non-employment of child labour is the stated or official goal of business organizations but some have the practice of employing them in violation of their official goals.

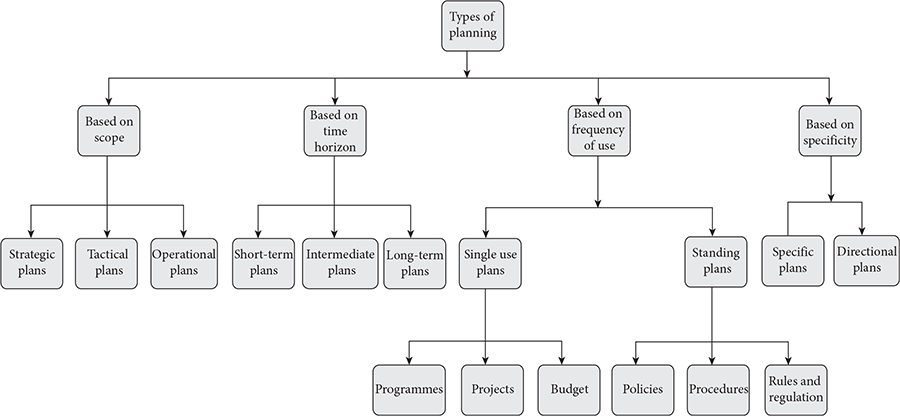

Types of Planning

Planning is applicable to all levels of management as plans can serve different purposes for different managers. Top management can formulate long-term plans for the whole organization. Similarly, first-line supervisors may develop short-term plans to manage the day–to-day activities at unit levels. An organizational plan can take different forms depending on its scope, time frame, degree of detail and frequency of use involved. In this:

- Scope refers to the range of activities covered by a plan. It may be sufficiently wide to cover the whole organization, or small and narrow to cover a unit.

- Time frame defines the period covered by a plan. The plan may be short-term or long-term.

- Degree of detail involves the specificity of the plan. The plan can be detailed or less-detailed.

- Frequency of use refers to the number of times a plan is actually used. It may be one time or multiple times.

Classifications of Planning

We shall now see the classifications of plans keeping these determinants in mind. Figure 4.1 shows the classifications of planning.

Classifications Based on the Scope and Degree of Details

Based on the scope and details, planning can be classified into three categories. They are: strategic planning, tactical planning and operational planning.

Strategic planning—Usually, strategic plans are formulated by the top authorities of organizations comprising the board of directors and top management. These plans pertain to the organization as a whole rather than to any specific department, division or individual. Strategic plans focus primarily on an organization’s environment, resources and mission. These plans are normally comprehensive in scope, relatively general (less detailed) and typically implemented over a long period of time. Strategic plans outline the broad goals for the whole organization and also state its mission (purpose of existence). It is a blueprint that drives an organization’s efforts towards goal accomplishment. However, these plans focus more on the relationship between the organizational members and those who work in other organizations. These plans must be adequately flexible to accommodate changes caused by the external environmental factors. These plans serve as basis for lower-level planning like tactical planning.

Tactical planning—Tactical plans are the detailed plans designed to implement the strategic goals and plans formulated by the top management. Tactical plans are derived from strategic plans. These plans normally offer details of how an organization will compete within its chosen area.24 Middle managers have the main responsibility of formulating and implementing tactical planning. Tactical plans can be defined as an organized sequence of steps designed to execute strategic plans.25 These plans focus primarily on people and actions.

Tactical plans normally have a shorter time frame than strategic plans. Plans that focus on the functional areas of an organization like marketing, manufacturing, financing and human resource are a few forms of tactical plans. The scope of tactical plans is generally broader than operational plans but is narrower than that of strategic plans.

Operational planning—Operational plans aim at converting the strategic plans into reality through specific, focused and short-term plans. It also aims at supporting the execution of tactical plans. Operational plans are usually derived from tactical plans. These plans are developed by department managers, and other low-level managers for carrying out the strategic and tactical plans through day-to-day activities. Operational plans identify the specific procedures and actions to be adopted by employees at the lower levels of the organization for goal accomplishment. These plans tell exactly what is expected from the departments, teams and individuals.

Operational planning involves the determination of specific steps, measurable goals and resource allocation necessary to fulfil the strategic goals. These plans can be prepared for a week, month or a year. These plans are typically viewed as a part of the implementation phase of strategic plans. Purchase plans, advertising plans, financial plans, facilities plans and recruitment plans are a few typical examples of organizational planning. Operational plans normally focus on the relationship prevailing among the people working within the same organization. A comparison of the characteristics of all three forms of planning is shown in Table 4.2.

Classifications Based on Time Horizon

Plans are normally classified into short-term plans, intermediate plans and long-term plans depending on the time period. Let us now see these plans in detail.

Short-term plans—These plans are formulated when the organizations want to accomplish their goals within a short span of time. The short-term plan period may not usually exceed a year. These plans normally become tools for management of day-to-day activities in departments, divisions, units, etc. Short-term plans are the steps that lead to the fulfilment of long-term objectives. In an uncertain environment, organizations prefer short-term goals and plans over long-term goals and plans. For instance, when technological, social, economical, legal and other changes are fast-paced, organizations may prefer short-term plans as they permit far more flexibility.26 These plans are normally expressed on a departmental basis like sales plans, purchase plans and manufacturing plans. Tactical planning generally belongs to short-term planning category. Lower-level managers are normally assigned with the responsibility of short-term planning.

Table 4.2 Comparison of Strategic, Tactical and Operational Planning

Short-term plans can be classified into: (i) action plans and (ii) reaction plans.27 Action plans are those plans that are formulated for accomplishing other plans (like tactical and operational plans) of the organization. Action plans offer detailed and sequential course of actions to be adopted for organizational goal accomplishment. Reaction plans are those plans that are prepared to tackle the organizational contingencies. Managers formulate reaction plans whenever there are unexpected or unforeseen developments in the environment that require some response from the organization.

Intermediate-term plans—Intermediate plans define the organizational activities important for the execution of long-term plans and goals. When the environment becomes uncertain organizations usually focus on intermediate planning as an alternative for goal accomplishment. Normally, long-term and intermediate-term plans are suitable for corporate and business level goals while intermediate- and short-term plans are fit for functional goals and strategies.28 These plans are useful for middle-level managers as they offer directions to them. Tactical planning is one form of intermediate planning. These plans normally cover a time horizon of one to two years.29

Long-term plans—Long-term plans are prepared when organizations require long periods of time to reach their goals. Strategic plans are usually the long-term plans of the organization. A long-term plan can provide a “big picture” of an organization and also indicate its future direction. Top management is normally involved in the formulation of long-term plans. Political, economic, legal and industrial conditions shape the long-term plans of a firm. These plans may cover a time period of two to five years or more. The major focus of long-term plans is on the profitability, return on investment, risk reduction, market share, new product development and market expansion of the organization. However, the time period of long-term plans will vary from one organization to another and from one industry to another.

Classifications Based on Frequency of Use

Plans can also be classified into single-use plans and standing plans depending on the number of times these plans are used in the organization. Let us see them now.

Single-use plans—These plans are generally prepared for one-time use. The aim of these plans is to meet the needs of a particular situation. They are developed to achieve non-routine and unique goals of an organization. The course of action developed as a part of these plans is less likely to be repeated in future and in the same form. Plans formulated by the management for completing acquisition or merger processes are examples of single-use plans. The important forms of single-use plans are: (i) programmes, (ii) projects and (iii) budget.

- Programmes—Programmes are single-use plans that are prepared to handle specific situations. They are helpful when a large set of activities are to be carried out on a target-oriented and time-bound basis. Each programme is normally a special and one-time activity for meeting a non-routine nature of goals. Programmes are expected to remain in existence only till the achievement of specific goals. They might contain procedures for uncommon activities such as introduction of new products, entry into new markets, opening new facilities, restructuring of business, etc. Each programme may also be associated with several projects. ISRO’s planned mission to the moon called Chandrayaan-2 is its ambitious programme for the future.

- Projects—Projects are another form of single-use plans but they are usually less complex in nature. Projects usually have shorter time horizon than programmes. Typically, projects can be a part of programme and also be independent, single-use plans. Special training to a group of employees who might be given special assignments after the planned business takeover can be a project, while the takeover itself is a programme. Similarly, development of cryogenic fuel by ISRO for its GSLV launch vehicle that will carry heavy payloads to the moon is an example of a project.

- Budgets—Budgets are another form of single-use plans. They are expressed in financial terms. A budget refers to the funds allocated to operate a unit for a fixed period of time.30 Budgets normally cover a specific length of time, say one year, and serve a specific purpose. Budgets can act as planning as well as controlling tools of an organization. In organizations, budget normally mentions how funds will be sourced and how such funds will be spent on labour, raw materials, overheads, marketing, capital goods, automation, etc. For instance, the Indian government has provided budget allocation of ₹ 82.50 crore for ISRO’s Chandrayaan-2 mission to the moon.31

Standing plans—These plans are used repeatedly because they focus on situations that recur regularly over a period of time. The primary purpose of standing plans is to make sure that the internal operations of the organization are performed efficiently. Standing plans are normally developed once and then modified to suit the changing business needs. These plans offers guidance for repetitively performed actions of the organization. Standing plans save the planning and decision-making time of the managers by guiding employees’ actions in the organization. These plans normally encompass a broader scope than single-use plans because they involve more than one department or function. Policies, procedures, and rules and regulations are important forms of standing plans.

- Policies—Policies are one form of standing plans that provide broad guidelines for routinely made decisions of the managers. Organization’s strategic plans and goals usually form the basis for framing the policies. In normal circumstances, policies are expected to define the boundaries within which decisions are to be made by the managers and supervisors. Policies are actually the general statements that are broad in scope and not always situation-specific. According to George R. Terry,32 policy is a verbal, written or implied overall guide, setting up boundaries that supply the general limits and direction in which managerial actions will take place. Policies can also explain how exceptional situations are to be handled by the managers.33

HR policies like hiring policies, compensation policies and performance evaluation policies are a few examples of an organization’s policies. Policies can be classified as: (i) originated policies (general policies formulated by top management for guiding employee actions, (ii) appealed policies (policies in full or part formulated in response to the specific request of the stakeholders), (iii) implied policies (policies that exist and guide decisions but are not explicitly approved by any competent authorities) and (iv) externally imposed policies (policies dictated by external agencies like government, unions, etc.).

- Procedures—Procedures are the standing plans that define specifically the steps to be followed for achieving specific goals. Procedures are also known by terms such as standard operating procedures (SOPs) or methods. Procedures are usually more specific than policies. Procedures state exactly what course of action is to be adopted by an employee in a particular circumstance. Past incidents and behaviours often provide the inputs for modifying and improving the existing procedures.

Procedures can be similar for more than one functional area of a business. For instance, organizations may adopt the same leave sanctioning procedure for all employees across the whole organization. Procedures can ensure consistency in the decisions of the managers in identical and recurring situations. Grievance handling procedure and disciplinary action procedure are a few instances of procedures.

- Rules and regulations—These are the narrowest forms of standing plans.34 Rules clearly state what is to be done by an employee in a specific situation. Regulations in turn regulate the behaviour of the organizational members in a programmed manner. Rules normally do not leave any scope for exercising options or decision making by managers. They do not supplement decision-making activities, rather they substitute them. For instance, when employees are late to the office, it drives the managers to a predetermined course of action. Similarly, when there is a non-payment by a trade debtor, it instructs the sales people to follow a standard practice without any deviation.

It is to be understood clearly that single-use plans and standing plans are not always used independently. Rather, single-use plans are often used with standing plans to aid in the accomplishment of the goals.

Prerequisites for effective policies—Policies are considered as an effective and indispensable management tool, every organization therefore expects these policies to be good, time-tested and realistic. The following characteristics can make policies effective.

- Clarity and brevity—To be effective, policies must be clearly written and laid out in an easy-to-read and understandable format. As far as possible, technical jargon and long sentences are to be avoided while writing policies.

- Adaptability—Since organizations operate in dynamic environments, it is important that their policies are sufficiently flexible. This flexibility will permit the management to carry out timely and need-based revisions in the policies. At the same time, it is also equally important to ensure that there is sufficient degree of stability in policies to achieve continuity in administration. There must be a reasonable balance between stability and flexibility.

- Comprehensiveness—Organizations must make sure that the policies are comprehensive enough to deal with any emergency situations that may arise when relevant plans are implemented.

- Ethicality—The policies of an organization must conform to the ethical standards of the organization and the society. Ethical policies specify an organization’s commitment to ethical practices. An organizational policy must respect human rights, ecology and social goodness to become an ethically sound policy.

- Ownership—The policy user must know clearly the ownership of a policy. They must know from where the policy originated and the management levels responsible for its maintenance. When the ownership of a policy is clear, it can substantially enhance its authority and effectiveness.

- Goal oriented—The aim of a policy is typically an organizational goal accomplishment. It is therefore important that the policy is linked to the broader objectives of the organization. Policies must also provide for proper coordination of activities of various interrelated units and subunits for effective goal achievement.

Classifications Based on Specificity

Based on the scope for different interpretations, plans can be classified into specific plans, directional plans, contingency plans and scenario plans.

Specific plans—Specific plans are well-defined plans that do not allow different interpretations by different managers. They ensure consistency and continuity in the decisions of managers. These types of plans are apt for organizations that enjoy stable external and internal environments. Clarity of organizational goals and objectives is an important prerequisite for formulating effective specific plans. A plan that aims at cutting the production cost by 3 percent in one year is an example of a specific plan. These plans are capable of minimizing and eliminating ambiguity, misunderstanding and other problems associated with any goal execution. However, these plans can restrict the freedom and creativity of resourceful managers.

Directional plans—Directional plans are general plans that offer a great deal of flexibility to the managers in goal formulation and execution. They provide a general direction in which the organization proposes to move forward but there are no specific plans or deadlines.35 Directional plans are best suited for uncertain and volatile organizational environments. The distinct feature of these plans is that they are sufficiently flexible to enable an organization to respond quickly to the unexpected developments in the environment.

Directional Plans provide focus to the managers without tying them down to any predetermined and specific course of action. However, these plans do not have the clarity of specific plans. They may cause misunderstanding and performance deviations. A plan that aims at increasing the corporate profit between 4 percent and 6 per cent is an example of a directional plan.

Contingency planning—Contingency plans are the specific actions to be taken by an organization in the case of crisis, setbacks or unforeseen circumstances. These plans become functional in the event of unexpected happenings with important consequences for the organization. Organizations operating in vastly uncertain environments usually develop contingency plans along with strategic, tactical and operational plans. Contingency planning is a process of identifying what can go wrong in a situation and getting ready with plans for managing them. Let us look at a few definitions of contingency planning.

“A contingency plan is a plan that outlines alternative course of actions that may be taken if an organization’s other plan of actions are disrupted or become ineffective.” —William M. Pride.36

“Contingency plans define company’s response to be taken in the case of emergencies, setbacks or unexpected conditions.” —Richard L. Daft.37

The need for contingency planning arises out of a thorough analysis of the risk that an organization faces. The risks may arise from internal factors like strikes, machinery breakdowns, key people’s resignation or hospitalization, accidents, fire or other disasters. It may also emerge from external factors like new technological developments, increase in cost of supplies, transport disturbances, sudden changes in interest rates, economic slowdown, government regulations, terror strikes, etc. Organizations can have separate contingency plans for internal contingencies and external contingencies. Typically, people who have given thought to contingencies and possible responses are more likely to meet major goals and targets successfully.38

Scenario planning—A scenario means a description of scenes. Scenario planning is basically a modern forecasting technique used in the planning process. It helps in learning about the future by understanding the nature and impact of the uncertain forces affecting the external environment of an organization. Scenario planning is an opportunity to generate a clear and imaginative background for thinking how to act in the future. In this type of planning, managers mentally rehearse different scenarios based on their expectation of diverse changes that could have an effect on the organization.39 In this type of planning, each scenario is seen as a story that has several possible endings. Group members discuss different endings for each scenario ranging from the most optimistic to the most pessimistic. They then decide how they would respond.

Scenarios can help in recognizing major changes and likely problems. They also help managers to improve their knowledge of the organizational environment. Further, they enhance and perfect the manager’s perception of possible future scenarios through mental rehearsals even before it actually happens. This allows for anticipation of the unexpected events and providing an early warning system. An automobile company can do a scenario planning for the impact of possible steep increase in fuel cost on its product sale.

Strategy

In a simple sense, strategy means “a systematic and detailed plan of action.” In business parlance, this term refers to the specific courses of action undertaken by the higher levels of the organization to accomplish pre-specified goals. Hill and Jones40 describe strategy as an action a company takes to attain superior performance.

The term, strategy, has its origin in the Greek word, strategus, which means commander-in-chief. It is actually a combination of two words—stratus meaning “army” and agein meaning “to lead.” Thus, it means to lead the army in its operations.

Levels of Strategy

Organizations can make strategies at three different levels. The focus and requirement of each strategy will differ depending upon the level at which these strategies are formed. The three major levels of strategy formulation are corporate, business and functional levels. However, the corporate level strategy is further classified as growth strategy, portfolio strategy and parenting strategy (Figure 4.2). However, it is absolutely essential that these strategies are internally consistent, mutually supportive and goal oriented.

Corporate-level strategy—This is the top level of strategy making in an organization. Corporate strategies usually deal with basic questions such as how to create value for the entire organization. Top-level managers make wide-ranging decisions concerning the scope and direction of the organization. Organizations usually make decisions on the market or industry product diversification, merger or amalgamation, and so on. Similarly, through corporate strategies, an organization decides on building organizational capabilities and core competencies. Corporate level strategy has three components: (i) growth strategy, (ii) portfolio strategy and (iii) parenting strategy. We shall discuss each of these strategies briefly.

- Growth strategy—Growth strategy deals with the development and accomplishment of growth objectives. It can be further classified into concentration strategy and diversification strategy. Concentration strategy is adopted by an organization when the business in the existing industry is safe, profitable and attractive for further expansion. The organization can implement concentration strategy through vertical or horizontal integration. In vertical integration, the organization develops strategies to expand within the existing industry by taking over the functions performed earlier by the supplier and others. In contrast, the horizontal integration involves the acquisition of additional business activities that are similar to the existing business activities. For instance, firms may acquire competitors’ business activities to reduce threat from competition. In diversification strategy, firms grow by expanding their operation into new markets, by introducing new products in the current market or by adopting both strategies. Growth strategies are often carried out through mergers, acquisitions and strategic alliances.

- Portfolio strategy—Portfolio strategy deals with determining the portfolio of business units for the organization. This strategy aims at constantly revising the portfolio of business units on the basis of risk and return. It views each business unit as an investment for the organization. As such, it aims at getting good returns out of each investment. The purpose of portfolio strategy is to allocate resources to those products or services that ensure continuous success or to those products that get greater returns but with high risk. Overall, portfolio strategy attempts to ensure that the collective profitability of all the businesses in the portfolio enables the organization to attain its performance objectives successfully.

- Parenting strategy—The parenting strategy, aims at allocating resources among the different business units of the organization with optimum efficiency. It seeks to build organizational capabilities across the business units of the organization. The strategy may involve, among others, identifying key factors of the organization, determining the priority in resource allocation, ensuring better utilization of resources and capabilities, and coordinating the different activities in an efficient manner.

Figure 4.2

The Levels of Strategy

Business-level strategy—The second level of strategy is the business-level strategy. It deals with questions like how to achieve a competitive advantage in each business that the organization is engaged. It is concerned with the development of the strategy for a single business organization. In the case of a diversified business organization, business-level strategy means formulating a strategy for any one of the strategic business units. Each business unit is treated as an independent unit and profit centre. It can develop its own business-level strategy in order to successfully compete in the market for individual products or services. It focuses mostly on creating and sustaining competitive advantage through price/cost leadership and product differentiation.41 For instance, factors like advanced technology, unique product features, superior HR skills, efficient distribution capabilities, and superior customer service can give competitive advantage to the unit. The strategy involves a deliberate decision to perform differently in the market to deliver a unique mix of values.42

Functional-level strategy—At the functional level, specific strategies are made for the functional activities of the organization. These are usually executable within a short period of time. Functional-level strategy may include production, marketing, purchase, finance, HR, research and development, and other similar activities of the firm. Each functional area covers several tasks. For instance, the HR function may include tasks like recruitment, selection and training. Here, the functional-level strategy will decide whether to carry out a task, (e.g., training) through in-house resources or to outsource the same. The functional strategies should effectively supplement and support the corporate and business strategies of the organization.

Finally, it is essential to ensure that all the strategies of the organization contribute effectively to the accomplishment of the overall objectives of the organization.

Approaches to Planning

The process of planning is closely linked to an organization’s internal and external environment. Planning is bound to change when there are changes in an organizations’ environments. Years ago, planning was viewed as the privilege of top managers with almost no role of employees. Consequently, traditional managements adopted a top-down approach towards planning. This attitude of managements began to change with the development of new management theories (like Management by Objectives (MBO)) and entry of knowledge workers in organizations. Now firms strongly believe that planning can be effective and successful only when employees are involved at every stage of the planning process. Approaches to planning can be classified as top-down execution and responsibility approach, bottom-up execution and responsibility approach and top-down policy and bottom up planning and executive approach. We shall now discuss the various approaches to planning.43

Top-down Execution and Responsibility Approach

This is the traditional approach to planning. As per this approach, planning is entirely the responsibility of the top management of the organization. Usually, these kinds of organizations keep an exclusive planning department to assist the management in formulating plans. The planning department will have specialized people with the responsibility to develop plans, procedures and policies. In this approach, plans developed by the top management will be sent down the organizational hierarchy for execution. At lower levels of the management, these plans are modified to suit the needs of individual departments.

The merit of this approach is that it makes the planning process a systematic and well-coordinated affair. The limitation of this approach is that the individual department may not get proper attention. For instance, department-centric issues can be overlooked. The planning personnel may not have the feel of the problems faced by the departments. Similarly, they may find it difficult to understand how data from various departments relate to the business on the whole. In an overseas survey of top-down approach, two-thirds of the managers viewed this approach as ineffective and disappointing.44

Bottom-up Execution and Responsibility Approach

In this contemporary approach, each department is assigned with the responsibility of developing and implementing plans according to the requirements. This approach ensures that organizational members at different levels are involved in the planning process. The involvement of employees also ensures their commitment to planning. Peter F. Drucker’s MBO is a classical example of the bottom-up approach (discussed later in this chapter).

In bottom-up planning departmental issues get due attention and the employees also get motivated to work harder for the success of the plans. However, the limitation of this approach is that planning could become a costly affair for the organization. Further, it becomes necessary for each department to train their staff in planning. The managers’ focus on core activity (like production activity for manufacturing department) could get distracted due to the planning activity. The department plans may not have the thoroughness and professionalism of centralized plans prepared by full-fledged planning departments.

Top-down Policy and Bottom-up Planning and Execution Approach

The purpose of this approach is to have the benefits of top-down and bottom-up approaches. In this approach, a centralized department like the planning department develops the planning policy and guidelines to be followed by all the functional departments. Conforming to these planning policies and guidelines, each department can develop and implement their own plans. This approach makes planning a collective endeavour of all levels of management. This approach ensures that plans are consistent and driven primarily by the overall organizational interests and priorities. But this approach can push up the cost of planning as people at different levels are involved in the planning process.

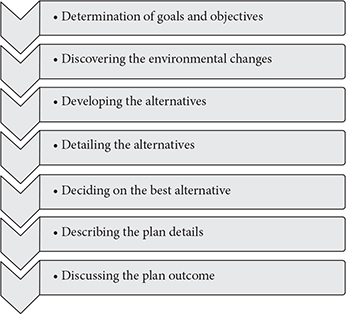

Steps in the Planning Process

Planning is never a one-time activity of a business, rather it is a continuous activity performed throughout the life of the organization. Planning is a process that involves several interrelated steps. A process is actually a system of operations that work together to produce an end result.45 The success of the whole organization is tied crucially to the effectiveness of its planning process. It is therefore essential for the management to have a proper process to develop plans in an efficient, orderly and recurring manner. Even though the steps in the planning process may vary from one organization to another, certain steps are important for all planning processes. Figure 4.3 illustrates the steps in the planning process.

Determining the organization’s goals and objectives—The success of planning depends on the ability of the managers to set and achieve goals and objectives. Organizational objectives should be set in the key areas of the operations. At the first stage of planning, managers must analyze the mission statement of the organizations to get inputs for goal-setting and planning activities. Mission statement profoundly influences the planning operations by providing it with focus, direction and limits. A well-defined mission is the basis for the development of all subsequent goals and objectives.46 Managers must also take into consideration the other influencing factors like environmental conditions, resources availability, employee skill inventory and ethical issues for determining the goals and objectives.

Managers must ensure that their goals and objectives are SMART, i.e. Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant and Time-based. These goals and objectives can be qualitative or quantitative in nature. In any case, goals must be verifiable. At the end of the planning period, managers must know whether they have accomplished the goals or not. For instance, if the goal is to conduct a 40-hour training programme for managers, it is a verifiable goal. In contrast, if the goal is to develop better managers, then it can become a non-verifiable goal. Once the goals are framed, managers get clarity on their target, time frame and direction.

Figure 4.3

Steps in the Planning Process

Discovering the environmental changes—Once the goals are established, managers should scan the internal and external environments to identify the factors facilitating and blocking the goal achievement. While evaluating the external environment, managers must first study the changes in the macroenvironment that affect all forms of organizations and industries. The macroenvironment analysis normally involves the analysis of social, political, technological, legal and political factors. Then, they should evaluate the changes in a microenvironment that comprises organizations belonging to a particular industry. They must specifically look for information pertaining to customer attitude and needs, recent trends in technological development, impact of technology on the organization and its existing product line, cost of labour, government policies, legal constraints, and strengths and weaknesses of suppliers and distributors.

Managers should then evaluate the internal environment of the organization. As a part of this analysis, managers must consider the need for and availability of various resources likes financial, physical, human, time and information resources. The internal environment analysis should also cover the internal factors like organizational culture, organizational structure, existing skill inventory of employees, operational capacity and efficiency, patent rights and market share. Managers would have a large amount of information on the organizational environment after the internal and external environmental analyses are done. This information should enable them to recognize the opportunities and challenges presented by the external environment and the strengths and weaknesses of the internal environment. This process can be done through SWOT analysis (discussed later in this chapter). By adopting appropriate forecasting techniques, managers can predict the future trends with a fair degree of accuracy and utilize them to accomplish the predetermined goals.

Developing the alternatives—Once the environment is scanned and the trend obtained, managers should identify different alternatives to reach the goals. Environmental analysis ensures that all possible alternatives are identified and included so that the best one can be chosen. The nature of the goal, the availability of information and the analytical ability of managers together determine the number and nature of alternatives generated by them. Though managers intend on developing organization-centred alternatives for goal accomplishments, a few generic (general) alternatives are also available. These generic alternatives can be applied to a wide variety of organizations. However, the development of alternatives can be limited by an organization’s objectives, philosophies and policies and also by the attitude of managers and employees.47

Detailing the alternatives—After managers develop all possible alternatives, they do Analysis of Alternatives (AOA). AOA is the analytical comparison of multiple alternatives before choosing the best alternative. The alternatives must be carefully analyzed in a systematic and logical way so that the most suitable alternative is chosen for implementation. The alternatives on hand can be evaluated by managers through qualitative and quantitative criteria. As a part of qualitative analysis, the strengths and weaknesses of each alternative are compared without the support of any numeric data and the best choice is made. It is actually a subjective analysis. In the case of quantitative analysis, alternatives are assigned with numeric values for comparison. For instance, when sales turnover, net profit, labour cost or any other numeric data on alternatives are used for comparison, it then becomes quantitative analysis. In the course of evaluation of alternatives, the performance of each alternative against the key parameters is assessed to identify the viable and non-viable alternatives. Finally, the managers must spell out clearly the possible positive and negative aspects of each alternative, especially as to how the alternatives address the goal requirements.

Deciding on the best alternative—After an analysis of the alternatives, managers must choose one best alternative for implementation. It is not possible for managers to pick up an alternative that has no possible negative consequences. Normally, they opt for a solution that has the highest probability of positive outcome with the least negative consequences. While choosing the best alternative, managers might consider the views and opinions of the higher authorities, employees and other participants. By choosing an alternative, the manager commits both time and organizational resources towards it. Quite often, such commitment becomes irreversible without substantial loss. Understandably, the managerial decision involving the selection of the best alternative has been the most crucial aspect of any planning process.

Describing the plan details48—Once the best alternative has been decided, it must then be implemented. Prior to its implementation, the plan details must be communicated to the employees responsible for its execution. Managers must describe the goals and plans to the employee in a comprehensive and timely manner to ensure their involvement and cooperation. Improper and inadequate information sharing may result in employee mistrust and apprehension about the motives of the plan.

Discussing the plan outcome—Once the plan is put into action, it is necessary for the managers to conduct “ongoing” or “end of plan” evaluation or both. Since planning is a continuous activity of the management, plan monitoring, evaluations and feedback are important aspects of the planning process. Midterm evaluation can help managers to check and ensure that the plans are leading to the desired end. In the event of deviations, managers can make instant corrections in the plan and avoid plan failures. The “end of plan period” evaluation can facilitate a thorough revision of future plans based on plan evaluation. Management can conduct feedback sessions with plan participants and beneficiaries to ascertain their views and complaints. Plans are usually evaluated in terms of costs, time limits and performance quality.

While formulating and implementing several plans at a time, managers must ensure that different plans are properly balanced and integrated so that they support one another and work in unison. In a dynamic environment, it is essential for the managers to continuously update the planning process by identifying and eliminating the weaknesses in the process on a real-time basis. The planning style of the Aditya Birla Group is discussed in Box 4.2.

Box 4.2

Corporate Cell—Planning Style of the Aditya Birla Group

Organizations carry out various kinds of planning ranging from highly complex to simple and basic. Depending on the needs and nature of the organization, managements can choose their own methods and techniques in the process of planning. The planning process of the Aditya Birla Group presents an interesting case.

The Aditya Birla Group has a corporate cell which provides a strategic overview to the management and also acts as a corporate consultant. This corporate cell is multi-dimensional in nature as it attends to the planning needs of the different group companies. The important cells of this group are Central Cell, Corporate Economics Cell, Corporate Affairs and Development Cell, Corporate Communications and CSR Cell, Corporate Finance Group Cell, Group Human Resources Cell, Group Information Technology Cell, Corporate Legal Cell, Corporate Management Audit Cell, Corporate Safety Cell, Health and Environment Cell and Corporate Strategy and Business Development Cell. Let us see the functioning of a couple of cells.

The Central Cell assists the chairman in strategic planning and monitoring of the group businesses. It supports the chairman in driving the planning and budgeting processes, conducting regular reviews and evaluating business performance, decision making on capital expenditure proposals, and formulating and implementing strategic initiatives.

The Corporate Economics Cell (CEC) interprets the business environment by continuously tracking, assessing, analysing and forecasting global and domestic economic trends and policies. It provides analytical inputs and economic information to different decision makers in the group at the corporate as well as business levels.64

Planning Premises

Planning premises refers to the assumptions or future settings against which planning would be carried out. In simple terms, planning premises can be viewed as the environment of plans in operation.49 It is concerned more with the external business environment of the organization. Planning premises can be defined as “the anticipated environment in which plans are expected to operate. They include assumptions and forecasts of the future and known conditions that will affect the operations of plans.”50 The anticipated environment of planning is often influenced by factors like marketing conditions, price levels, laws, government policies and regulations, political stability, population trends, tax structure, trade cycles, business location, labour market conditions, capital availability, material and spare parts availability and so on. Planning premises are capable of influencing the planning process, particularly the goal determination and plan implementation stages.

The determination of planning premises is actually the result of forecasting the future environment by managers. This forecasting is crucial not only to determine the plans but also to work out the planning premises. However, the focus of forecasting is on the general business environment when determining the planning premises. In contrast, the focus of forecasting in planning is on business-specific factors such as future returns from investments.

Planning premises are often organization-specific or industry-specific and they are rarely common for all types of organizations. Planning premises can be classified into internal premises and external premises. Internal premises are organizational-specific factors like sales forecasting, supplier constraints and distribution bottlenecks. External premises are general environmental factors that are external to the organization. Factors like socio-economic environment, political and legal environments, industry environment, product market conditions and labour market conditions constitute external premises.

Effective and accurate planning premises ensure the following: (i) development of well-organized plans, (ii) decrease the risks of uncertainty in environment, (iii) improve coordination among the different elements of planning, (iv) increase plan flexibility and (v) improve the success rate of plans.

Barriers to Effective Planning

Organizations are managed and controlled by the top executives only through a series of plans. The nature and type of planning also indicates the philosophy, attitude and the outlook of the management. Further, planning also helps the employees form an opinion about their employers. Through effective planning alone, management can assure itself of good governance, employee cooperation and mission accomplishment. However, the effectiveness of planning is undermined by the presence or absence of a few factors. It is essential for the managers involved in the planning process to know these factors. Let us now discuss barriers to planning.

Unsuitability of goals—Goals that are difficult to be measured or verified can undermine the effectiveness of planning. For instance, job satisfaction of employees is difficult to be quantified, and hence goals pertaining to employee satisfaction are difficult to be measured. Similarly, impracticable, unethical or over-ambitious goals can also affect the effectiveness of planning. For example, driving the competitor out of market through unethical methods or bribing official for receiving favours are examples of unethical goals. Further, misalignment among organizational goals like promotion of one goal to the disadvantage of other equally important goals can also harm the planning as well as the business interest. For instance, overemphasis on credit sales target may have a negative effect on the goals of the debt collection department.

Dynamic environment—Generally, plans are more suitable for stable environments. Managers operating in a rapidly changing and complex environment may find the environment difficult to develop effective planning. The problem of planning under dynamic environment is more difficult in long-term planning than in short-term planning.

Fear of failure—Plans are made for the future, which is full of uncertainty. The future may hold surprises for even meticulously prepared and well-laid out plans. The risk of unexpected and sudden developments often discourages managers from undertaking planning in a real and extensive manner. Further, goals and plans often create expectations about managers and the failure of plans can be viewed as the managers’ personal failure. The fear of failure and consequence of failures act as barriers to effective planning by managers.

Resistance to changes—Plans will arouse resistance when employees perceive the need to change the manner in which they do their job. Since plans are often viewed as an instrument of change, employees may tend to oppose them as a matter of routine. Such resistances may cause anxiety and hesitation among managers and also discourage them from undertaking the planning exercise.

Inadequate resources—The success of planning often depends critically on the resources made available to it. In the event of non-availability of adequate resources, managers may be forced to curtail plan-related activities. Inadequate budgetary support and the resultant compromises can undermine the effectiveness of planning. Further, the over- or underestimation of resources and capabilities can also cause problems for managers at the time of plan implementations.

Lack of effective communication—Adequate and timely communication of goal and plan details is a prerequisite for effective communication. When there is difficulty in communicating plans to the participants, the plans may fail due to the absence of proper understanding, coordination, employees’ commitment and cooperation. Poor communication may be caused by the employees’ language or cultural differences, managers’ poor communication skills, complexity of planning process and ineffective communication instruments.

Absence of creative thinking—A constant flow of new ideas is essential for planning in a dynamic environment. The development of new ideas, products, methods and technology is possible only for people with creative thinking. Managers with stale and standardized thoughts often fail as planners due to their inability to think originally and grow in new directions while formulating plans. These managers also fail to inspire the employees and bore them with unimaginative and unremarkable plans. The smartest managers are those who are able to spot and nurture great ideas from little expected sources.51 Understandably, the lack of creativity in the planning process can also be the result of exclusions of employees in idea generation and plan development.

Managers’ indifference—Managers’ preoccupation with routine work and their tendency to focus more on immediate results may make planning a less important activity in their busy schedule. Managers often find it difficult to allot the required time to plan properly due to their hectic nature of work. They are also less motivated to spend their time for preparing broad plans that may benefit them and their organization only in the long term.

Lack of follow-ups—Feedback allow the planning system to change its performance to achieve the desired results.52 However, in practice, little attention is paid to the participants’ feedback and plan follow-ups as long as the plan goals are attained. Managers fail to understand that it is not enough to know that the plan is working well, but they also need to know why and how it works. When they do not know, it will be difficult for managers to solve when a plan goes wrong or when circumstances change. Managers’ attitude of managing plans by results alone can affect the effectiveness of the planning process.

Inaccurate planning premises—The planning process is mooted under certain assumptions of future events. The accuracy of these assumptions is determined by the ability of the managers to forecast the role and relevance of mostly environmental factors in influencing the planning process. In the event of inaccurate assumptions, plans are bound to fail due to the increased risk of uncertainty, poor coordination, etc.

Informal and casual planning—Managers often make informal short-term plans to tackle an emerging situation. Such an informal approach to planning may lead to the negligence of long-term goals, problems and interests of organizations. The absence of formal planning guidelines may lead to ad hoc and inconsistent plan development and execution.

Expensive exercise—Planning is often viewed as a costly and time-consuming exercise by many organizations, especially the small and medium ones. The cost of planning further goes up as the planning becomes more complex, elaborate and formal. The difficulties of managers in justifying the high cost of planning, often reduce planning to an inconsequential exercise.

Steps to Make Planning Effective

Planning must lead to success rather than failure. If for some reasons planning fails, it may cause crisis and panic, which may be costly and painful for the organization. It is therefore imperative for managers to carry out continuous improvements in the planning process to make it effective. We shall now discuss a few requirements that can make planning an effective exercise.

Top management support—The success of any planning process critically depends on top management’s support, commitment and involvement. The active and sincere involvement of higher managements in the planning process usually inspires confidence and collaboration among lower levels of management. Moreover, the plans that require major changes in the organizations’ practices, structure and style must enjoy the full patronage of the top management for its successful implementation.

Proper and timely communication—Effective communication plays a pivotal role in the success of planning process. Without adequate communication within the organization, goals become unclear and plans lack coordination. Top management must make certain that managers are well-trained in communicating the plans, goals, policies and procedure to employees. It must also ensure the presence of a well-organized system for communication among different groups involved in planning and execution activities. This would ensure that everyone connected with planning has a common understanding of how and when plans are to be formulated and implemented.

Adequate availability of resources—Adequate resources must be committed to the development and implementation of effective plans. In this regard, managers must make an accurate assessment of plan requirements in terms of organizational resources and ensure that these resources are utilized in a timely and effective manner.

Constant revision and updating—Specific and sincere feedback about the efficacy of planning process should be obtained from the plan participants and other stakeholders of business. Such feedback must form the basis for reviewing the planning process and also for initiating changes and improvements, if necessary.

Participatory approach—It refers to the wider involvement of employees in the planning and goal-setting process. In organizations, participatory approach to planning improves motivation, learning, self-esteem and feeling of ownership among employees. Participation in planning also makes employees partly responsible for the success or failure of plan initiatives. Management can involve employees at every possible stage of the planning process. Employee participation is also the best way to overcome the resistance to the planning process.

Adequate rewards—Plan-linked rewards play a major role in securing the willing cooperation of organizational members for plan implementation. Management must ensure the presence of rewards for effective execution of organizational plans. It must also make sure that employees are aware of the existence of these rewards.

Sufficient and effective control—Planning and control are highly dependent on each other for effectiveness. For instance, effective planning is also a prerequisite for effective control.53 Management must analyse, identify and eliminate the deficiencies in the existing controlling practices. It should then put in place an effective mechanism for constantly monitoring and controlling the planning activities.

Positive attitude—Managers with a positive attitude can handle any situation courageously. Further, positive thinking enables managers to take chances or risks in their jobs. Further, positive managers tend to view difficulties in the environment as challenges and tackle them confidently. The principle of positive thinking helps managers to offer their best in any situation.54 Organizations must cultivate a positive attitude among its members by developing a positive culture and thought process.

Climate for creativity—Organizations need to develop a climate that encourages and rewards people who exhibit creativity, risk-taking attitude and free-wheeling thoughts in goal setting and planning. Members must also have enough freedom to express their ideas, opinions and oppositions while formulating plans. Since creativity in the planning process is important to avoid obsolescence and increase performance, managers must: (i) develop a desire to be creative, (ii) accept that each problem has some creative solution and (iii) believe that they are the ones to find it.

Accurate planning premises—Plans may fail due to wrong assumptions about the expected environmental conditions at the time of plan execution. Planning assumptions or premises often go wrong due to inept forecasting of the future. Managers must improve their forecasting skills and techniques to make more accurate planning assumptions and premises.

Proper integration of goals—Overall goals of organizations are typically accomplished through a series of interdependent but dissimilar goals and plans. In the absence of proper coordination, these goals and plans may work with cross purposes leading to their failure. It is hence essential for management to ensure proper coordination among two or more interdependent plans executed to achieve a common goal.

Management by Objectives