CHAPTER 7

Organizational Structure

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Understand the meaning and characteristics of organizing

- Enumerate the importance of organizing

- Explain the principles of organizing

- Describe the process of organizing

- Understand the meaning and definitions of organizational design

- State the meaning and definitions of organizational structure

- List the factors affecting organizational design and structure

- Describe the types of organizations

- Understand the meaning and definitions of organizational chart

- Explain the benefits and limitations of job specialization

- Enumerate the factors influencing the span of management

- Describe the meaning and purposes of departmentalization

- Understand the bases and types of departmentalization

India’s Inspirational Managers

Lakshmi Mittal is the chairman and CEO of ArcelorMittal, the world’s leading steel and mining company. Mittal founded Mittal Steel in 1989, and guided its strategic development till it merged with Arcelor in 2006. He is today considered as a pioneer in mergers and acquisitions after this mega merger deal. This company has presence in more than 60 countries and has employed 198,517 people as on 2017. It has earned a revenue of US $68.67 billion (2017). Mittal believes that the lean organizational structure of ArcelorMittal has played a vital role in its efficiency. Mittal strongly believes in decentralization, since his company has a commitment to ensuring different parts of the business are empowered to make decisions, and ensuring accountability at the right level within the company. Moreover, Mittal’s company has created a flexible organizational structure that facilitates the smooth acquisition of numerous steelmaking and other companies. The global steelmaker Mittal uses the size, structure and worldwide reach of his company to optimize the resources and services across the company and also to achieve economies of scale in operation. With this information in the background, let us discuss the different aspects and importance of organizing in this chapter.

Introduction

As a managerial function, organizing aims at bringing together the necessary physical and human resources to achieve the organizational goals and plans. If organizational goals and plans define what to do, organizing defines how to do it.1 The primary purpose of organizing is to bring order to the organization so that there is no confusion and commotion in the conduct of the business. It involves determining how necessary resources and activities of an organization can be effectively arranged and integrated to perform the predetermined functions. It is actually a process of defining and grouping of activities and then establishing authority−responsibility relationship among them. Organizing also helps managers to build, develop and maintain working relationships, which is essential for achieving organizational objectives. The basic principles of organizing are universal in nature even though each organization may have different size, stature, goals and environment.2

An organization is nothing but a whole consisting of several unified parts (departments). The role of organizing here is to properly divide the whole into parts and then unify these parts in an orderly manner to achieve the organizational goals, vision and mission. We shall now see a few definitions of organizing.

Definitions of Organizing

The ultimate result of organizing as a process is the creation of an organization. Most definitions of organizing focus on the organizational goal accomplishment through proper arrangement and allocation of activities, authority and resources among people.

“Organizing is the process of designing jobs, grouping jobs into units and establishing pattern of authority between jobs and units.” —Ricky W. Griffin.3

“Organizing may be defined as arranging and structuring work to accomplish an organization’s goals.” —Stephen P. Robbins.4

“Organizing is the process of engaging two or more people working together in structured way to achieve a specific goal or set of goals.” —James Stoner.5

“Organizing is defined as the deployment of organizational resources to achieve strategic goals.” —Richard L. Daft

We may define organizing as a process that involves the arrangement and grouping of organizational activities and resources, and establishment of relationship among them with a view to fulfil the organizational goals.

Characteristics of Organizing

Based on the definitions, the following are the characteristic features of organizing:

- Organizing is a goal-directed activity, i.e. the common purpose of organizing is the accomplishment of organizational goals and objectives.

- Organizing is a differentiating activity. This is because it involves the identification and classification of activities into a variety of processes and activities for accomplishing the larger task (namely the goals) of the organization.

- It is a grouping activity as organizing involves the grouping of activities into manageable units like department, teams, etc.

- It is assigning or delegating activity as organizing involves the assignment of groups to different competent authorities (such as managers and supervisors) with necessary authority to oversee their performance.

- Organizing is an integrating activity as it involves proper coordination of the efforts of various manageable units to achieve the organization’s overall purpose.

- It is a dynamic and constantly evolving activity as organizing likely to change intermittently depending upon the significant changes in an organization’s environment.

Box 7.1

Flat and Flexible—RAL’s Organizational Structure

Whether big or small, each company must consider the way in which its organization is designed and structured. It should also determine the basic characteristics that its organizational structures should possess. These essential characteristics normally help organizations to operate effectively and efficiently and to grow continuously. A small organization, for instance, may need a simple organizational structure. As it grows in size and becomes more complex, the organizational structure too needs to grow and change. As such, the designing of an organizational structure is often considered as a continuous process. Radiohms Agencies Limited (RAL)—one of India’s largest FMCG marketing companies—has the following characteristics in its organizational structure.

The chief characteristics of RAL are as follows: (i) it has a flat structure with fixed levels of reporting or increased responsiveness. This should also enable the organizational members to play enriching roles and diversify their skillsets, (ii) it has a dynamic and constantly evolving structure in tune with the fast and feverishly changing national and world business parameters and (iii) its structure clearly defines the role and relationships of organizational members, even while remaining flexible.60

Box 7.1 shows the characteristics of the organizational structure of an FMCG marketing company.

Importance of Organizing

Organizing is an important function of management that facilitates the implementation of planning. Managers use organizing function to make best use of the available resources and also to get things done through others in the organization. For instance, organizing enables managers to concentrate their physical and human resources in a unified way to convert their plans into reality. We shall now discuss how important the organizing function is to managers.

- Facilitates goal accomplishment—The outcome of an organizing function is the creation of a basic structure in the organization. This structure acts as a tool of management to realize the organizational goals and plans. It guides and regulates the deployment of resources by organizations for achieving their strategic goals.

- Clarifies the work environment—Organizing enables managers to determine clearly the tasks to be done, persons to whom these tasks are to be entrusted with and how these tasks are to be done. Organizing thus brings clarity to individuals, teams and departments about their tasks, authority and responsibility. Well-defined authority and responsibility enables the management to keep the work environment free of any job-related misunderstanding, tensions, and disturbances.

- Enhances job specialization—Organizing involves the division of larger task into several smaller tasks to be performed by departments and individuals on a continuous basis. When these tasks are repeatedly performed by the same departments, teams or individuals, it eventually helps them to become experts in their activities. This specialization is essential for improving the productivity of organizations and the efficiency of individuals.

- Improves coordination—Various activities of the organization are planned and carried out in different departments. There are further divisions and sub-divisions of operations within these departments depending on the nature of tasks involved. It is necessary to effectively coordinate the activities of the different departments to achieve the common goals. Requirements for effective coordination among departments, units and teams are better served through the organizing function. This is because the organizational structure creates authority heads for each designated task. These heads normally coordinate all the activities related to the tasks.6

- Allows well-defined reporting relationship—Organizing allows managers to develop reporting relationship among the organizational members in a systematic manner. This well-defined reporting relationship provides for orderly progression of information from bottom to top and top to bottom for decision making and decision implementation in an uninterrupted way.

- Facilitates staffing—Organizing enables the management to determine the staff requirements by indicating the nature and number of people required at different levels of the organization. It also helps organizations in determining the knowledge, skills and ability requirements of the employees to fill the roles designed into the structure. The outcome (staff vacancies) of the organizing process becomes the input for deciding the hiring plans of the organization.

- Avoids duplication of efforts—As a part of organizing, managers identify all activities necessary to accomplish the goals. These activities are then classified and assigned to different departments and teams. This process ensures that none of the tasks remains unassigned, wrongly assigned or assigned twice. Organizing thus helps organizations to make certain that there is no overlapping or duplication of efforts and initiatives.

- Boosts employee satisfaction and motivation—Organizations that have strong and consistent structure created through organizing normally make employees feel secure and motivated. Managers, through the organizing function, clearly define the job, authority and responsibility of each employee of the organization. Clarity in the organizational structure and work environment allows employees the opportunity to fulfil the organizational goals as well as their personal needs. Organizational structure is capable of boosting the employee satisfaction and motivation. In contrast, when there are cracks in the structure, managements run the risk of losing their best employees due to lack of job satisfaction and motivation.

Principles of Organizing

Principles of organizing refer to the basic assumptions or beliefs underlying the organizing function. Most of these principles are drawn from the famous management thinker and practitioner Henri Fayol’s fourteen principles of management. As illustrated in Figure 7.1, the important principles of organizing are as follows: (i) principle of chain of command, (ii) principle of unity of command, (iii) principle of unity of direction, (iv) principle of span of control, (v) principle of specialization, (vi) principle of coordination, (vii) principle of delegation, (viii) principle of flexibility, (xi) principle of parity of authority and responsibility. We shall now discuss them briefly here.

- Principle of chain of command—The chain of command refers to the line of authority or reporting relationship that exists within an organization. The principle of chain of command states that the line of authority should be hierarchical and the authority flows from the top to the bottom. This principle also states that an unbroken and clear chain should connect all the employees with their higher authorities all the way to the highest levels. This principle usually favour a mechanistic structure with a centralized authority. It also ensures that all employees know whom they report to and also who reports to them.

- Principle of unity of command—This principle states that every employee of the organization should report to one boss or superior only. They should also be answerable and accountable to that boss for all their activities. Similarly, this superior should be responsible for giving orders and information to employees, evaluate their performance and assist them in performing their duties well. Further, the superior must be responsible for encouraging and motivating the employees to do better. Again the superior should appreciate the employee’s good performance or initiate corrective actions in the case of performance deficiency. The principle of unity of command aims at ensuring that there is: (i) no confusion among the employees about whom they should get orders from, (ii) no duplication or conflict in the orders passed down; for instance, an employee may get two conflicting messages from two bosses, (iii) mutual understanding and supportive relationship between the superior and the subordinate, (iv) an opportunity for the superior and the subordinate to be aware and appreciative of one another’s strengths and weaknesses and (v) less opportunity for avoiding or shirking duties and responsibilities by the employees under the pretext of carrying out another boss’s instruction.

- Principle of unity of direction—The principle of unity of direction states that all the activities of the organization should be directed towards the accomplishment of the same objectives. It also advocates that all activities that have similar goals should be placed under a single supervisor.7 Further, this principle insists that every organization should have only one master plan or one set of overriding goals.8 This principle is violated when, for instance, purchase department buys materials which are low cost and low quality while the overall commitment of the organization is to sell quality goods.

- Principle of span of control—This principle deals with the number of employees a supervisor can effectively manage. This principle states that there is limit to the number of persons reporting to one supervisor. The more the number of employees supervised by a supervisor, the wider the span of control. Similarly, the fewer the number of employees supervised, the narrower the span of control. Usually, an organization with narrower spans will have comparatively more number of levels in its structure than the one with wider spans. Thus, the span of control is normally in proportion to the height of the organizational structure.9

- Principle of specialization—This principle states that each employee should perform one leading function. According to this principle, when employees carry out limited number of tasks assigned to them, they eventually acquire specialization in those tasks. Division of labour is an important prerequisite for specialization. In this regard, all related functions are grouped together under one manager. For instance, all production-related activities can be grouped and assigned to the production department under the control of the production manager. In this way, the entire organization can be divided into different functional departments through the process called departmentalization. Specialization through departmentalization is the best way to use individuals and groups.10 Job specialization is discussed in detail in the later part of this chapter.

- Principle of coordination—This principle states that the organizational resources and activities should be coordinated through collaborative relationships. Combining and correlating all the organizational activities is the essence of coordination. The principle of coordination aims at ensuring that different departments, teams and individuals of the organization work collectively for the common purpose. Normally, the degree of coordination between various tasks depends on their interdependence. The greater the interdependence between departments, the greater the coordination required.

- Principle of delegation—Delegation is the process of allocating authority and responsibility for the goal achievement of an organization. Delegation of authority means the downward transfer of the right to act, to decide and to fulfil the job responsibilities. The purpose of delegation is to get the work done more efficiently by another. The principle of delegation assumes that organizational tasks will be distributed to members according to their skills, knowledge, experience, training and other relevant qualities.

- Principle of flexibility—Flexibility means the adaptability to changes in an environment. The principle of flexibility insists that some exceptions to rule must be permitted. This is important because of the uncertain and unpredictable nature of the organizational environment. Therefore, organizational structure must be sufficiently flexible to accept the changes in its internal and external environments. This principle also states that the factors affecting the flexibility of the organization like red tape, excessive control and burdensome procedures must be eliminated. At the same time, organizations cannot afford flexibility by sacrificing stability altogether. They need to strike a balance between flexibility and stability as reasonable stability is also equally important for accomplishing the long-term goals of the organization. Box 7.2 discusses the organizing principles of HUL.

- Principle of parity of authority and responsibility—The principle of parity states that the authority delegated to employees should equal the responsibility entrusted with them. This is necessary to get the work done through them without any job dissatisfaction and frustration. In the absence of sufficient authority, employees cannot fulfil their job responsibility. At the same time, they may try to misuse their authority without corresponding responsibility.

Figure 7.1

The Different Principles of Organizing

These principles of organizing are important guidelines for managers at every stage of the organizing process. They can guide them effectively when they have to make decisions relating to organizing functions.

Box 7.2

Principle of Organizing—The HUL Approach

The management approach towards the organizing function is normally guided by more than one principle. Managements look to achieve a precise combination of principles that facilitate the smooth conduct of the business activities and effective accomplishment of organizational goals. The approach of Hindustan Unilever Limited (HUL)—India’s largest fast-moving consumer goods company—towards organizing presents an interesting case.

The fundamental principle determining the organizational structure of HUL is to empower the managers across the company’s nationwide operations and infuse speed and flexibility in its decision making and implementation processes. This company also considers transparency and accountability in decision making and execution as the two basic tenets of its corporate governance. All the activities of HUL including its organizing function are driven by an aspiration to serve consumers in a unique and effective way.61

The Process of Organizing

Organizing process is vital for the organizations to achieve their goals and objectives. The primary purpose of organizing is to make possible an orderly use of the organizational resources. The organizing process aims at converting the plans into reality through the planned and purposeful deployment of physical and human resources within the decision-making framework called organizational structure.11 The end result of this organizing process is the creation of an organization. Organizations created through efficient organizing process can have improved capabilities, superior productivity and performance, and employee satisfaction and motivation. The basic steps in the organizing process, as shown in Figure 7.2, are generally universal in nature.

- Recognizing the organization’s goals, plans and operations—The organizing process usually begins as soon as the goals and workable plans are formulated. Plans guide the organizing process by influencing the decisions regarding the activities to be carried out for goal accomplishment. It is therefore necessary for the managers to first examine and recognize the nature and duration of the organizational goals and plans as a part of the organizing process. Plans and goals are dynamic in nature, managers must therefore review them from time-to-time to decide whether any changes in the organizational structure or activities are required.

- Deciding the goal-related activities—Managers must determine the specific activities required for achieving the plans and goals of the organization. They can prepare a list of all the activities or tasks that need to be carried out for plan execution. At this stage, managers usually break down a potentially complex job into several simpler tasks or activities.

- Grouping of work activities—Once managers know what specific tasks or activities are to be done, they classify and group these activities into workable units. They normally group these activities into a logical pattern or structure.12 Such grouping of activities is known as departmentalization. Usually managers adopt the principle of functional similarity (similarity of activities) for classification and grouping activities. For instance, grouping of activities can be done on the basis of functions (marketing, production, etc.), products, customers, geographical locations, etc.

- Assigning activities and authority to specific positions—Once the activities necessary for goal accomplishment are identified, classified and grouped, managers allocate these work activities to specific individuals. They should also assign the required resources to the people for successful completion of the work. Appropriate authority must be delegated to the employees to enable them to complete their tasks. Management generally applies the principle of functional definition for assigning activities and authority to specific positions. This principle insists that the type and quantity of authority to be delegated to the individuals should be in proportion to the nature and significance of the activities assigned to them.13

- Coordinating the divergent work activities—Managers should coordinate the activities of different individuals, groups and departments within the organization. Normally, managers are expected to decide between vertical and horizontal relationships for various levels within the organizational structure.

A vertically structured relationship indicates the decision-making hierarchy of the organization. This kind of structuring normally leads to establishment of different levels in the organizational structure from the bottom to the top of the organization. It also provides details of who should report to whom in the organization and also within in the various teams, departments and divisions.

A horizontally structured relationship indicates the working relationship prevailing among the different departments. It also indicates the span of control for different managers and supervisors of the organization. The organizational structure becomes complete once the various activities of the organization are coordinated and directed towards goal accomplishment. At this stage, managers can use organizational charts to develop the diagrams of the relationships.

- Evaluating the outcome of organizing process—Organizational goals and plans are dynamic in nature, organizational structure should therefore be flexible enough to accommodate the changes in the goals and plans. It is hence essential for managers to periodically evaluate the results of the organizing process to know the effectiveness of organizing functions in achieving the stated goals and mission. Based on the results of such evaluation, managers can modify the existing organizing process and organizational structure. They can also introduce a new organizing process to replace the old ones for developing vibrant organizational structures. Box 7.3 outlines the structure transformation initiatives of a telecommunications company.

It should be clear by now that the organizing process helps managers to establish working relationship among the members necessary for goal accomplishment. Managers may choose a specific organization type for establishing relationship among the members of choice making is known as organizational design.

Figure 7.2

Steps in the Process of Organizing

Organizational Design

The first major task of managers engaged in organizing is the development of an organizational design. Organizational design involves the creation of a new organizational structure or modification of an existing organizational structure. Designing organizational structure is not a one-time event for an organization.14 It is actually a formal and guided process of integrating the activities and resources of an organization on a continuous basis. Organizational design process helps managers to solve two important but complementary problems of organizations. They are: (i) how to divide a big task (organizational goals) of the whole organization into smaller tasks or sub-units and (ii) how to coordinate these smaller tasks efficiently to accomplish the bigger task.15 Organizational design involves multidimensional approach as it deals with human components and structural components. The human component normally includes, among others, the people, processes, rewards, coordination and control. The structural components include organizational objectives, goals, plans, strategies and structure. Management normally adopts a top-down approach to the organizational design process by working from the top to the bottom.

Box 7.3

Customer-centric Structure—Airtel’s Transformation

Managements generally prefer organizational structures that enable them to proactively embrace change in a timely manner to make the best use of opportunities in their environment. The new organizational structure introduced by Bharti Airtel Limited—a leading integrated telecommunications company—is a case in point.

Bharti Airtel’s business operations have been structured based on its technologies into three strategic business units, i.e., mobile services, Airtel telemedia services and enterprise services. However, it has introduced a new organizational structure in 2011 for its business operations in India and South Asia. The guiding factor for Airtel in shaping its organizational structure has changed from “technology” to “ customer.” The new customer-centric structure is aimed at achieving greater business and functional synergies, offering a common interface to customers, and creating a de-layered and more agile organization. Airtel’s transformation from its conventional tall structure to the flat structure will also facilitate enhanced employee empowerment, job autonomy and employee engagement. Further, this new “business to customer” (B2C) and ”business to business” (B2B) based structure is aimed at providing enhanced business efficiency and employee value to the company.62

While designing the organizational structure, managers normally consider the nature of goals, strategies, people, environment, technology and activities of their organization. Effective alignment of structure, process, people, strategy, metrics and rewards with the goals and plans of the organization is the primary aim of any organizational design. The key elements that influence the decisions relating to organizational design are job specializations, job grouping (known as departmentalization), reporting relationships among positions (known as chain of command and span of management), distribution of authority (centralization and decentralization) and coordination.

Definitions of Organizational Design

The primary focus of definitions on organizational design is on the creation or modification of organizational structure. We shall now look at a few definitions of organizational design.

“Organizational design is the process of assessing an organization’s strategy and environmental demands and then determining the appropriate organizational structures.” —Hitt.16

“Organizational design is the process by which managers select and manage aspects of structure and culture so that an organization can control the activities necessary to achieve its goals.” —Jones.17

“Organizational design is the determination of the organizational structure that is most appropriate for the strategy, people, technology, and tasks of the organization.” —James Stoner.18

“Organizational design is the design of the process and people systems to support organizational structure.” —Richard M. Burton.19

The ultimate aim of organizational design is to produce a structure that fits the strategic plans of the organization. Organizations may face disturbances in the event of mismatch between their goals and structure.

Organizational Structure

Organizational design involves the designing of organizational structure by managers for grouping the activities and then allocating them to different units, departments and teams. As discussed earlier, once these activities are assigned, formal authority and responsibility relationship is established among these departments and teams. To make the organizational structure viable, authority is delegated throughout the organization and a mechanism is established for coordinating diverse organizational activities.

Organizational structure is a powerful instrument for reaching organizational goals and objectives. In this regard, managers must ensure a perfect fit between the organizational plans and organizational structure to achieve success. Generally, the goals and size of organizations determine the nature and types of organizational structures. For instance, large organizations may keep extensive and complicated organizational structure. In contrast, small organizations may have comparatively simple and straightforward structure. In any case, while designing or modifying a structure, managers must have thorough knowledge of the existing environment, technology and system of social relationships among members. Generally, organizational structure can be classified into tall structure and flat structure based on the number of subordinates managed by each manager called span of management (discussed later in this chapter).

Definitions of Organizational Structure

Managerial experts explain organizational structure as a framework for gathering, dividing and allotting resources for goal accomplishment. We shall now look at a few definitions of organizational structure.

“Organizational structure is the framework in which the organization defines how tasks are divided, resources are deployed and departments are coordinated.” — Richard L. Daft.20

“Organizational structure is defined as the sum of the ways an organization divides its labour into distinct tasks and then coordinates them.” —Hitt.21

Types of Organizations

Based on how authority is distributed, decisions are made and tasks are performed, organizations can be classified into three fundamental types. They are: (i) line organization, (ii) line−staff organization and (iii) committee organization. Even though several other forms of organizations may exist, they are only the variation or combination of these three basic forms. We shall now discuss these three forms.

Line Organization

Line organization is the oldest and simplest method of organization. This type of organization is found to be suitable mostly for smaller firms. However, the true form of line organization mostly exists in military systems. Line organizations are also called ‘doing’ organizations where all activities from the production to marketing of goods are controlled by the managers/owners. In the case of companies with line authority, managers maintain direct control over all the activities carried out in their respective departments. They are also directly responsible for achieving the organizational goals and plans.

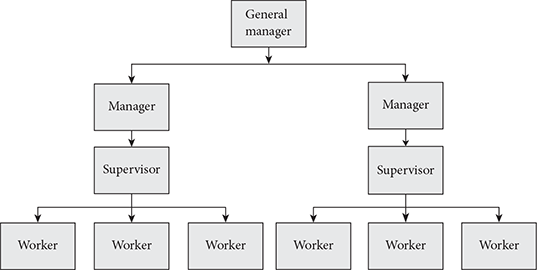

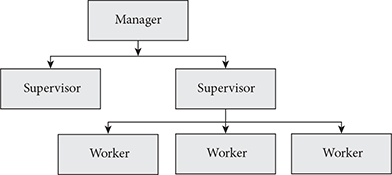

In line organization, a well-defined line of authority and communication flows downwards from the top-level managers to the workers at the bottom through various hierarchical levels. As such, authority will be greatest at the top level and then gets gradually reduced through each successive level in the hierarchy. Line organizations are ideal for slow-paced and stable organizations, where moderately educated people are employed in significant numbers. The authority of managers in line organization is primarily legitimate and formal. Figure 7.3 depicts the line organizational structure. We shall now discuss the merits and limitations of line organizations.

Merits of line organization—The important merits of a line organization are as follows:

- It is a simple and “easy to understand” form of organization without any complex organizational structure or chain of command.

- It encourages managers to act independently and improve their decision-making ability.

- It facilitates an organization to make managers wholly accountable for all their decisions and actions. Thus, they will be more careful while exercising their authority and doing their duties.

- As the whole department operates under the direct control of one manager, it is easy to coordinate the activities within his area of operation. Managers can also ensure better discipline among the employees as they report to an undivided authority.

- As too many persons are not involved in the decision-making process, managers in line organizations can make faster and timely decisions in unstable environment. They can thus make the best use of available opportunities to improve organizational interest.

- This structure can also be cost-effective as there will be less time and resources spent on meetings and consultations. The cost of staffing can also be less as there would be fewer or no advisors to assist the managers of line organization.

Figure 7.3

Line Organizational Structure

Limitations of line organization—Line organizations have several weaknesses too. They are as follows:

- There may be less technical depth and specialization in the decisions of managers in line organizations. This is because managers do not normally get any specialized advice from experts while making decisions. So, there are more chances that managers make arbitrary, hasty and unbalanced decisions.

- The Line organizations place greater emphasis on one-way top to bottom communication. The job involvement and satisfaction of employees at lower levels can be less in these organizations. Employees at the lower levels may not get adequate opportunities to communicate their complaints, suggestions and feedback to the higher authorities.

- When absolute authority is given to managers, they may try to misuse their position and authority which may harm the organizational interest. This method may encourage the employees to be passive and too dependent on their managers. At the same time, it may encourage the managers to be more autocratic and impulsive in their approach.

- When there is overreliance on line managers for administration and decision making, organizations may not be able to develop the administrative, leadership and decision-making skills of non-managerial personnel in the organization. This can affect the succession planning and leadership development programmes of the organization.

- Effective coordination of activities across departments or divisions may be difficult in this form of organization. This is because line managers without any centralized advice may focus more on their departmental issues and interest. They may fail to consider the needs and interest of other departments adequately while making decisions.

- The job of line managers may become tiring and exhaustive due to heavy work pressure. This is because line managers are expected to plan, implement, monitor and control the organizational activities all by themselves.

To improve the operational efficiency of line organizations, a modified version of line organization, namely, line−staff organization was introduced. Let us now discuss line−staff organizations.

Line−Staff Organization

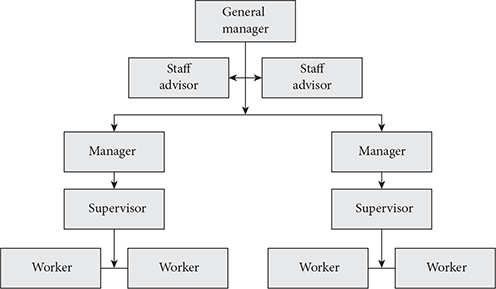

A line–staff organization is one in which the line manager gets advice and assistance from the staff manager (also called advisor). This kind of organization includes both line and staff positions in its structure. Large and more complex organizations normally prefer line−staff setup to improve the quality of the managerial decisions.

The role of line authority in these organizations is to make decisions and issue directives necessary for goal accomplishment. The role of staff advisors is to offer advice to the line authorities when needed. The staff departments in these organizations normally provide expert advice and other specialized support services to the line managers. This advice should enable line managers to make sensible, balanced and technically superior decisions. Figure 7.4 shows the line−staff organizational structure.

Thus, the major function of staff department is to collect or create necessary information, analyse them carefully and present them in the form of advice to aid line managers in goal accomplishment. However, they cannot compel the line managers to accept their advice. Line managers have the right to take or leave the advice of the staff managers. The staff function mostly remains a behind-the-scene activity in these organizations. This is because the staff managers do not normally have any authority over the staff of line departments. The staff advisors do not have any legitimate or formal authority over line departments.22 The core activities in organizations like production, marketing and finance are normally carried out by line managers. However, they can seek the advice of staff departments like human resources management, legal counselling and public relations, whenever necessary. We shall now do an evaluation of line−staff organizations.

Benefits of line−staff organizations —Let us first see the important benefits of line−staff organizations.

- This method enables the line managers to make well-informed and technically superior decisions with the aid of specialized staff advisors. This method is capable of combining the unique features of line departments like faster decisions, and direct communication with staff departments for specialized advice.

- Since thinking and acting are largely separated in line−staff organizations, line managers can allot more time for administrative works. This is possible because they can leave activities like problems analysis, data gathering, information processing and decision making to their staff advisors.

- This method eventually enables line managers to learn the techniques of effective decision making through consultations with staff experts. In this way, it provides training to the line manager in decision-making aspects.

- Due to the involvement of staff advisors, decision-making processes are now more methodical and disciplined. This should reduce the chances of decision failures as line managers are prevented from making any arbitrary and hasty decisions.

- Line−staff organization can help the management in achieving enhanced productivity, performance and profitability of the organization. This is possible as better and more accurate decisions mean reduced risk, better resource utilization and less wastage, and improved job satisfaction for managers and subordinates.

Figure 7.4

Line−staff Organizational Structure

Limitations of line−staff organizations—Let us now discuss the limitations of line−staff organizations.

- Even if authorities are clearly defined, the possibility of conflict between line managers and staff advisors cannot be completely ruled out. This is because their understanding of the problem itself can be different due to their dissimilar backgrounds and different approaches. For instance, labour disturbances in the production department can be viewed differently by the production manager, a line authority, and the HR manager, a staff advisor. Production managers may view it as a wilful disturbance of production schedule while HR may consider it as an outcome of strained labour−management relations. Ego clashes between the line manager and staff advisor can also cause conflicts in their relations, especially when latter’s advice is ignored.

- This method can push up the cost of administration as organizations have to pay for their specialist staff advisors in addition to the usual staff cost of line managers.

- Line managers blindly and indiscriminately following all the advice of the staff advisors are a distinct possibility in these organizations. This can happen when line managers become too dependent on the staff advisors.

- Since staff advisors often have little or no exposure to line managers’ tasks, responsibilities and difficulties, their advice may lack practicality.

- Since line managers alone get the recognition and appreciation for best decisions and efficient administration, staff managers may lack proper motivation to perform their job well.

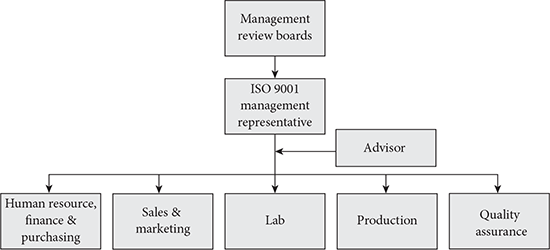

Committee Organization

When groups of individuals are given the authority and responsibility necessary for performing certain tasks or for making decisions on certain matters, it is called a committee organization. This type of organization is often viewed as another form of line−staff organization. In committee organizations, certain specific tasks will be performed not by an individual manager but by a group of individuals. Figure 7.5 shows the committee type of organizational structure.

The primary purpose of committee organizations is to supplement line−staff functions.23 These committees can exist either permanently or temporarily in organizations. Permanent committees perform the job of staff advisor by providing specialized advice to managers almost on a recurring basis. In contrast, temporary committees are formed for specific purposes and get dissolved when these purposes are fulfilled. Development of new products, fixation of revised pay for employees and identification of the cause of the declining sales are a few reasons for which committees can be formed. We shall now discuss the merits of committee organizations.

Merits of committee organization—Some of the merits of committee organizations are as follows:

- Recommendations of committees are more practical and acceptable because their decisions reflect the views of members with varied expertise and interests. This is possible as committee members are usually drawn from different functional areas like production, marketing, HR, etc.

- Committees act as an important forum for the organizational members to share their views, ideas and suggestions either directly or through their representatives. These committees are thus capable of improving employee motivation as they can find their views and opinions included in the recommendations of the committees.

Figure 7.5

Committee Organizational Structure

Limitations of committee organization—The important weaknesses of committee organizations are as follows:

- Decision making is normally a slow and time-consuming process in committee organizations. As such, committees are not usually effective when decisions are to be made quickly without any waste of time.

- In committee organizations, members may prefer a “mid-path” in decision making as a part of compromise to settle conflicting interest of the members. This may prevent the committees from choosing the best solutions to the organizational problems.

- Committees may push up the cost of administration as it may involve additional expenditures for organizations. For instance, managements have to bear the cost of committee meetings, time loss and work disturbances when members attend these meetings.

- Status and designations of the individual members may influence the outcome of group deliberations in committee organizations. Powerful members may attempt to put pressure on other members to get their views and decisions accepted. This may affect the sanctity and purpose of the decision making in committee organizations.

- The authority to make decisions is collectively exercised. It is therefore difficult to fix individual responsibility for decision failures. This may make members reckless and adventurous in making decisions.

In addition to the above, management can also opt for one more form of organization called matrix organizations. We shall now discuss the features of this organization.

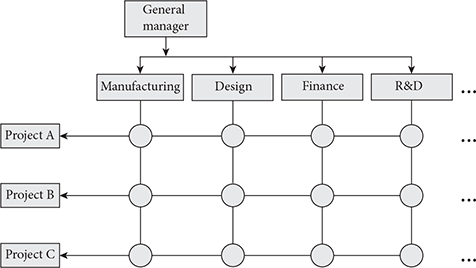

Matrix Organization

Matrix organization is usually formed when employees from different functional departments are required collectively for the execution of a project. The primary purpose of matrix organizations is to get the advantages and eliminate the disadvantages of other forms of organizations.24 Matrix organization usually has a grid form of organizational structure, where employees from different departments are linked. Figure 7.6 shows the matrix organizational structure.

The two-boss structure and dual reporting relationship are the essence of any matrix organization. In matrix organizations, each member should report to the manager of the cross-functional project as well as the manager of the functional department that deputed them to the project. For instance, when an executive of the fabrication department of an engineering unit is deputed to a large project under the control of another manager, he would report to both the fabrication department manager and the project manager. Matrix organizations facilitate the horizontal flow of skills and information within an organization. We shall now discuss the merits and limitations of matrix organizations.

Merits of matrix organizations—The merits of matrix organizations are as follows:

- They facilitate the effective integration of individuals and groups from different functional departments as members of one single matrix organization. This can encourage the members to work more unitedly and purposefully towards project goal accomplishment.

- These organizations are capable of increasing the effectiveness of communication system, conflict resolution process and coordination among members. It can also enhance the team spirit, commitment and involvement of the members.

- The cross-functional nature of matrix organizations enables every member to understand the needs and difficulties of other functional group members. This makes the members more empathetic and sensitive towards the problems of other departments even after they return to their own functional departments.

Figure 7.6

Matrix Organizational Structure

Limitations of matrix organizations—Matrix organizations suffer from a few limitations. They are as follows:

- The scope for conflict between the functional managers and project managers are high in matrix organizations, especially when the roles are not well defined

- The two-boss system and divided authority can create stress for the members of project organizations. When conflicting orders are given by the functional boss and project boss, members may feel anxious and confused in deciding whose orders are to be carried out immediately.

- It is difficult to design, develop and understand the structure of matrix organizations as they are often vague and complex.

- The cost of administration can go up when separate structure and organizations are created to manage projects. Establishment of a matrix organization may call for recruitment of managers, development of new infrastructure and fixations of higher remuneration for deputed staff. The result of all these would be high administration cost.

Organizational structures are normally written in the form of a chart for defining and outlining the role and responsibility of the organizational members.

Organizational Chart

Organizational chart is a tool used by the management for describing the organizational relationship. It is a visual representation of the organization presented in a diagrammatic form. This chart serves different purposes for the organization. For instance, it shows the major functions performed by the department, nature of relationship of functions or departments, channels of supervision and communication, line of authority, titles of positions or jobs located within the departments or units.25 We shall now look at a few definitions of the term organizational chart.

Definitions of Organizational Chart

Most definitions of organization chart describe the visual representation of the organizational structure. We shall now look at a couple of these definitions.

“Organizational chart is defined as the visual representation of the whole set of underlying activities and processes in an organization.” —Richard L. Daft.26

“The visual representation of an organization’s structure is known as organizational chart.” —Stephen Robbins.27

Organizational chart assists managers in different ways. In employee orientation programmes, it can be used by managers to show where each job is located in the organizational structure and also its relationship with other jobs in the department. Organizational chart can also depict the relationship of one department with the others and also to the whole organization. It also maps the flow of authority lines of different managers within an organization. It is an essential and effective tool for managerial audit at the time of auditing the management practices. Organizational chart enables the management to spot and recognize, discrepancies and inconsistencies in the organizational structure with ease.

However, these charts will be of little use if they are not updated periodically. Further, organizational charts recognize only the formal lines of authority and communication. More often, it ignores the informal channels of communications. Organizational charts can only supplement, and not substitute any organizational manual in employee orientation programmes.

Elements of Organizational Design and Structure

While designing the organizational structure, managers normally consider six key elements. These elements are: (i) division of labour and job specialization, (ii) departmentalization, (iii) chain of command, (iv) span of management, (v) hierarchy of authority—centralization vs. decentralization and (vi) formalization. Organizing thus involves decisions by managers regarding each of these key elements. We shall now discuss these elements in detail.

Division of Labour or Job Specialization

When the total workload is divided into different activities or tasks, it is called division of labour. In other words, the breakdown of jobs into narrow and repetitive tasks is known as division of labour.28 Through division of labour, individual employees can gain job specialization by performing a part of an activity rather than the whole activity. This job specialization enables individuals to perform their jobs attentively, comfortably and effectively. An organization may opt for any one of the three different degrees of specialization, namely, low, moderate or high specialization. Job specialization is often seen as a normal extension of organizational growth.29 Let us now discuss the benefits of job specialization.

Benefits of job specialization—Job specialization offers several benefits to organizations. They are as follows:

- Employees gain expertise and competency when they perform simple and small tasks repeatedly.

- Job specialization helps in reducing the training requirements of the employees as they perform single or specific tasks only.

- It simplifies the selection process as employees are often required to have specialization in any one area only.

- It reduces the transfer time loss between tasks as the employees rarely perform different tasks. Transfer time loss refers to the time gap between the end of one task and the beginning of another task.

- It helps organizations to develop task-specific and specialized equipment to assist with the job since the tasks are clearly and narrowly defined.30

- It enables supervisors to manage relatively large number of employees as they are well-versed with their job and seek little assistance from their supervisors.

- It enables managers to set exact performance standards for the employees and facilitates faster detection of job-specific performance problems.

- It is easier for managers to find replacements for the employees who perform single and specialized task as the substitutes can be trained within a short time and at less cost.

Limitations of job specialization—Though job specialization can provide multiple benefits, it also causes certain disadvantages to the organization. They are as follows:

- Employees performing specialized jobs may become bored and disillusioned with their jobs as the jobs do not normally offer any challenge or inspiration. Job boredom may lead to high level of absenteeism, attrition and other productivity problems.

- Overconfidence arising out of job specialization may tempt employees to compromise their safety, resulting in accidents and injuries.

- Lack of intrinsic satisfaction (satisfaction obtained from the performance of the job) may affect the quality of work life of employees. It may also make it difficult for them to strike proper balance between the work and family.

Departmentalization

An organization does not feel the need for division of its activities into different units as long as it remains small, simple and straightforward. This is because the owner-cum-manager can personally supervise the activities of all his/her employees. However, such personalized supervision may not be possible when the organization reaches a certain size, volume of trade or geographical dispersion. At this stage, organizational activities are divided (departmentalized) and assigned to managers who would look after these activities on behalf of the owners. In academic institutions, for instance, the need for departmentalization is considered as a function of growth in size, specialization of knowledge and faculties desired for autonomy.31

Since the activities cannot be randomly grouped, organizations follow certain norms, bases or plans. The grouping of organizational activities based on these norms and processes is called departmentalization. Adopting any of the logical bases, managers can classify and group activities into related, manageable work units. The ultimate purpose of any such grouping is the effective accomplishment of organizational goals and plans. Groupings can be done by managers on the basis of functions, geographical locations, products or service types, process used for manufacturing or customer categories. Sales people working together in the sales department or production people working together in the production department are examples of departmentalization. Organizations may also create hybrid organizational structures through the combination of various departmentalization types.32

Definitions of Departmentalization

The primary focus of departmentalization is on the grouping of organizational activities. Let us now look at a few definitions of departmentalization.

“Departmentalization may be defined as the process by which a firm is divided by combining jobs in accordance with shared characteristics.”—Jerry W. Gilley.33

“Departmentalization is the process of grouping jobs according to some logical arrangement.”—Ricky Griffin.34

“The grouping into departments of work activities that are similar and logically connected is called departmentalization.”—James stoner.35

Departmentalization thus refers to the grouping of organizational activities according to certain logical bases for organizational goal accomplishment. Let us now discuss the purpose of departmentalization as derived from these definitions.

Purpose of Departmentalization

The major purposes of departmentalization are to:

- Group the individuals with common background and shared characteristics.

- Define the relationship of positions within an organization.

- Establish formal lines of authority and fix clear responsibility and accountability.

- Provide job specialization to organizational members.

- Increase the economies of scale (cost reduction through enhanced production).

When management achieves success in forming effective departments, it can expect desired improvements in: (a) organizational performance and productivity, (b) managerial communication, (c) employee commitment, involvement and motivation and (d) the quality of decisions.36

Having seen the purposes of departmentalization, we shall now discuss the common bases for departmentalization.

Bases for Departmentalization

As a part of organizing function, activities of an organization can be divided and grouped on any one of the bases discussed here.

Functional departmentalization—When departments are formed on the basis of the specialized activities or functions performed by an organization, it is called functional departmentalization. Organizational functions like finance, production, purchasing, human resource and marketing form the basis for this type of departments. Organizational functions are different from the managerial functions such as planning and organizing. Functional departments are the traditional and most common form of departmentalization. Moreover, the functional approach to departmentalization is considered to be the logical way to organize departments.37 Functional departments are interdependent in nature and frequently interact with one another to accomplish organizational goals. Members of each functional department normally report to the functional managers of the departments. Smaller organizations generally prefer functional forms of departments. We shall now do an evaluation of functional departments.

Merits of functional departments—As a traditional form of department, functional departments offer several benefits to organizations. They are as follows:

- In functional departments same or similar activities are performed by the members, it is therefore easier for the functional managers to supervise the activities of their departments. For instance, a manager with market expertise manages the marketing department and so on.

- Functional departmentalization simplifies the training procedure and also reduces the cost of training. This is because departmental members are required to have relatively narrow sets of skills only.

- It facilitates in-depth specialization as employees perform same or similar activities on a repetitive basis.

- Effective coordination of the activities within the department is made simple and possible.

- Functional managers can effectively guide and motivate their department members as all of them have a similar technical background. Managers are usually well aware of the nature and requirements of each job and also of the skills, knowledge and orientation of their employees.

Limitations of functional departments—Functional departments also have some major limitations. They are as follows:

- As functional managers and members usually have specialized knowledge and narrow perspective, it may be difficult for them to understand and appreciate the problems of other functional departments. They may also overlook the organizational priorities and goals by giving undue importance for departmental matters, interests and priorities.

- Decision making is likely to be slower in organizations with functional departments. This is because inter-departmental coordination may not be effective due to the homogenous nature of the individual departments.

- Fixation of responsibility and accountability for organizational results may be difficult. This is because the individual functional department cannot be held directly responsible for any failed organizational mission. For instance, it is tough to decide whether a new product failed due to marketing factors, production factors or finance factors.

Product departmentalization—When organizational activities are classified and grouped on the basis of the product or services sold, it is called product departmentalization. In this kind of departmentalization, all activities connected with each product, including its production, marketing, etc., are grouped together under one department. In this way, an organization will have a separate department for each of its products. An organization may prefer product departmentalization when its products require distinct production strategies, marketing strategies, dedicated distribution channels, etc. The top managers of the product departmentalization normally have complete autonomy over the operations. Large, diversified companies often adopt product departmentalization for grouping their activities.38 Box 7.4 provides information on the production departmentalization of the Michelin Group.

Box 7.4

Many Facets of Michelin Group’s Organizational Structure

Even though managements may use different bases for creating departments at different levels, the basis for departmentalization at the highest level usually reveals the direction, dimensions and priorities of organizations. In this regard, the organizational structure of Michelin—the world’s leading tyre manufacturer—is worth mentioning here.

The Michelin Group is organized into product lines to gain superior understanding of its market condition and customer needs and preferences. It has eight product line departments each with its own marketing, development, production and sales resources. To support its product lines, it has eight geographical zones, 13 group departments in charge of support services and four performance departments like logistics and supply chain performance departments. Through its organizational structure, Michelin looks to increase responsiveness while dealing with customers, to expedite decision making by decentralizing responsibilities, to enhance the group’s profitability and performance, to strength research to achieve lead-in technological advances over their competitors and to accelerate growth by achieving better access to new markets.63

Merits of product departmentalization—Product departmentalization brings in many benefits to organizations. They are as follows:

- Decisions can be made quickly as the managers in charge of these departments deal with all aspects of products, such as production, marketing, financing, etc.

- It is easier to integrate and coordinate all the activities or functions connected with a product or service.

- Product departmentalization makes it possible for the management to fix accountability for the performance of each department directly, objectively and accurately.

- It facilitates the departments to remain in close touch with the customers and also keep their needs and requirements in constant focus.

- It enables the organization to obtain specialization in specific products or services.

- It helps organizations to develop managers in a comprehensive manner in all aspects of the organization like production, marketing, etc. This in turn assists the management in succession planning, especially for top managerial positions.

Limitation of product departmentalization—This form of departmentalization has some limitations. They are as follows:

- Since each department performs the same set of functions, such as market research and financial analysis, it often leads to duplication of functions and resources. It eventually leads to increased administrative cost for the organization.39

- Managers may view their products as more important even to the exclusion of other products from their organization. In this process, they may also compromise the overall interest of the organization.

Customer departmentalization—When the organizational activities are grouped on the basis of the type of customers served, it is called customer or market departmentalization. The primary purpose of customer departmentalization is to ensure that organizations respond to the requirements of a specific customer or a group of customers efficiently. It also enables organizations to have continuous interaction with their customers. For instance, banking companies normally use customer departmentalization to deal with the needs of their different class of customers such as business people, salaried people, agriculturists, etc. It has some strengths and weaknesses. They are as follows:

Merits of customer departmentalization—Customer departmentalization can assist an organization in several ways. Some of them are as follows:

- Customer departmentalization helps organizations to better understand their customers so that they can be more effectively segmented and targeted by their products or services. This should enable organizations to create best possible products or services necessary for increasing customer satisfaction, loyalty and organizational revenues.

- It enables organizations to provide specialized skills to the staff to deal effectively with the customers assigned to them. It thus enables organizations to provide personalized services to valuable customers through specialized staff.

- The customer-centric approach to departmentalization implies that the customers are central to the organization. This approach keeps the focus of the organizations on the customer requirements rather than on the products or functions.

Limitations of customer departmentalization—This method has some weaknesses and they are as follows:

- Customer departmentalization requires organizations to have more staff to look after the requirements of different classes of customers. This can obviously push up the administrative cost of these organizations.

- Management may find it difficult to achieve effective coordination across different customer departments of the organization.

- In customer departments, employees may take decisions that delight the customers immediately without ascertaining the long term effects of such decisions. For instance, trade discounts, special schemes and other offers can make the customers happy but have the potential to affect the organizational interest in the long run.

- Similar to product departmentalization, customer departmentalization can also lead to duplication of functions and resources affecting the profitability of the organization.

Geographical Departmentalization

When the activities of an organization are grouped on the basis of the geographical territory, it is called geographical departmentalization. The purpose of this departmentalization is to locate the operations of an organization, such as the sales office, production plants and after-sales service centres, close to the market area. These departments are responsible for carrying out the activities in the assigned geographical areas. It enables organizations to provide local focus to their operations. For instance, Life Insurance Corporation of India (LIC) has adopted geographical departmentalization for grouping its activities. It has a central office, eight zonal offices, 105 divisional offices and 2048 branch offices across the country to serve different regions. Transportation companies too normally prefer geographical departmentalization when they operate in several market areas. Similarly, global companies that market their products or service across nations often adopt geographical departmentalization. Let us now look at the merits and limitation of this method.

Merits of geographical departmentalization—Departmentalization based on geography can offer several benefits. These benefits are as follows:

- Geographical departmentalization enables organizations to respond quickly and effectively to the customer needs and requirements without needless loss of time.

- It helps organizations to be aware of the changes in the customer needs, tastes, preferences and other aspects of the market.

- Region-specific issues and problems get due attention in the decision-making process of the organization. This method also provides for faster and effective solution of regional issues.

- Experience gained at the regional levels is a good training for managers at higher levels.40

- It can help organizations to reduce cost by keeping the unique organizational resources closer to the market.41

Limitations of geographical departmentalization—This form of departmentalization has some weaknesses. They are as follows:

- Since the departments are geographically dispersed and physically separated from one another, it is difficult to coordinate their activities effectively. This problem becomes more acute when the departments are located in different countries, separated by thousands of miles.

- Organizations usually require large administrative staff for supervising the activities of the employees working in different geographical departments.

- This kind of departmentalization often results in the duplication of organizational resources and functions. For instance, high inventory cost is often the outcome of geographical departmentalization.

Process departmentalization—When the organizational activities are grouped on the basis of product or service processes used, it is called process departmentalization. Usually, the technical functions involved in a manufacturing type organization form the basis for process departmentalization. Mostly, economic and technological factors guide the decisions relating to departmentalization based on process. In this type, the need for coordination is more as the quality of output often depends on the degree of coordination among different processes. Process departmentalization is better suited for organizations that have environment and technology, which is homogenous, clear and stable.42 Manufacturing organizations that have machines requiring special operating skills and technical facilities prefer process departmentalization.43 The typical process departments for a sugar-manufacturing company are cleansing and grinding, juicing, clarifying, evaporation and crystallization, refining, separation and packing. Now we shall discuss the merits and limitations of process departments.

Merits of Process Departmentalization

The merits of process departmentalization are as follows:

- Process departmentalization helps the members to gain an in-depth job specialization by enabling them to sharpen their technical skills and knowledge in specific and limited areas.

- It ensures logical and effective flow of work activities necessary for smooth and hassle-free production of goods.

- This method is better suited for work activities which involve the use of specialized equipment and skills. This is possible because specialized equipment is vested with separate departments, which are made responsible for their operation and maintenance.

- It facilitates effective supervision of employees as they often have a common background with the same or similar knowledge and skills.

- It makes the departments interdependent and collectively responsible for productivity and performance. This necessitates the departments to foster better cooperation and coordination.

Limitations of process departmentalization—A few limitations of this method are as follows.

- This method is not universal in nature as it cannot be adopted by all forms, sizes and nature of organizations. This method is ideal only for certain types of products or goods.

- Though the departments are interdependent, it is difficult to ensure effective coordination. This is because the departments may concentrate more on department-level issues and problems, even overlooking the overall organizational interest and goals.

- It will be difficult for organizations to provide comprehensive skills and knowledge to the managers due to their limited exposure and experience.

Matrix departmentalization—When two or more forms of departmentalization are used for grouping the organizational activities, it is called matrix departmentalization. It is a hybrid nature of organizational structure.44 This structure is usually a mixture of functional, product, geographical, process, customer or any other traditional form of departmentalization. The primary objective of matrix department is to take advantage of the strengths of conventional forms of departments and to avoid their inherent weaknesses.

The well-known form of matrix departmentalization involves a combination of functional and product forms of departmentalization. For instance, the sales department of an organization may be classified and grouped on the basis of the various products manufactured. However, an organization may also combine other forms of departmentalization (like geographical and functional) to form matrix department. For example, a matrix department may be formed by locating the marketing department of an organization at different geographical locations of the country. Generally, matrix department is ideal for project type of works because they cover some or all of the organization’s departmental areas. Matrix departmentalization is commonly found in multinational corporations. It provides necessary flexibility to deal with multiple projects, programmes or product needs and to take care of the regional differences, if any.45 Let us take an evaluation of the matrix form of departmentalization.

Merits of matrix departmentalization—Matrix departmentalization can offer multiple benefits to an organization. They are as follows:

- Matrix departmentalization is helpful in ensuring high level of cross-functional interaction among members of different departments.

- It is capable of reducing and eliminating duplication of functions and resources. This is possible because the functional departments depute specialized employees from their department to matrix departments on a need-based manner for a specific time period.

- This method is appropriate for effective execution of huge and complicated projects as necessary physical resources and human resources (experts) can be quickly drawn from other departments.46

Limitations of matrix department—The major limitations of this method are:

- There is a scope for misunderstanding and conflicts among the managers of matrix departments and functional departments leading to confusion in project executions. Managers of functional departments may not be too willing to relieve their best people for matrix departments fearing work disturbances in their own departments.

- Coordination may be difficult among different departments, especially when the organization has several ongoing projects at a time.

- Scarcity of managers with diverse skills required for managing complex matrix departments may affect the formation and performance of these departments.

Time-based departmentalization—Organizations can also form time-based departmentalization to organize their activities. In time-based departmentalization, time becomes the basis for classifying and grouping the organizational activities. Organizations operating on a shift basis are an example of departmentalization by time. For instance, factories may operate on three-shift basis for all 24 hours in a day with separate functional departments and managers for each shift. This form of departmentalization ensures optimum utilization of the organizational resources.

Even though each type of department can bring some benefits to the organization, management should choose a departmentalization type that best suits the organizational needs and helps it to fulfil the short- as well as long-term goals. We shall now discuss the common benefits of departmentalization to organizations.

Benefits of Departmentalization

Organizations can get several benefits from departmentalization of its activities. They are as follows:

- Departmentalization enables managers and members of the departments to acquire specialization in their work because they perform certain repetitive works available within their department.

- Since different departments work under the care of different specialized managers, it is easier for an organization to achieve faster and balanced growth. In the absence of departmentalization, it is difficult for organizations to grow beyond certain levels.

- As each department is assigned with specific and well-defined work and goals, it is relatively easy for the higher management to fix responsibility for any performance lapse, failure and incompetency.

- Through departmentalization, managerial authority is decentralized across the organization. This ensures that the department managers have real and meaningful autonomy to make decisions and also involve the workers in the decision-making process.

- Organizations can make best use of the resources as duplication of functions and resources are considerably reduced through the departmentalization process.

- Top management can train and develop its managers for higher positions by initially assigning them administrative duties and responsibilities at different departments.

- Performance measurement and comparison for career advancement and wage fixation can be done more effectively at departmental levels. This is because employees at the departmental level are often involved in similar and comparable nature of activities only.

- Departmentalization enables organizations to respond quickly and effectively to the customer needs and complaints. It thus ensures better customer service.

Limitations of Departmentalization