CHAPTER 13

Leadership

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Understand the meaning of leadership

- Define the characteristics of leadership

- Distinguish between leadership and management

- List the steps in the process of leadership

- Enumerate the various theories of leadership

- Describe the recent trends in leadership approaches

- Understand the leadership succession planning

India’s Inspirational Managers

Shiv Nadar is the founder and chairman of HCL, a leading global technology and IT enterprise with annual revenues of USD 6.3 billion. The HCL enterprise comprises two companies listed in India, HCL Technologies and HCL Infosystems. The HCL team comprises 92,000 professionals of diverse nationalities operating in 31 countries including India. Time magazine has referred to HCL as an “intellectual clean room where its employees could imagine endless possibilities.” HCL, under Nadar’s leadership, developed an uncanny ability to read ahead of any market inflexion point and adapt itself to derive maximum advantage. Consequently, HCL revolutionized Indian technology and product innovation with many world firsts to its credit. With a capacity to think strategically and build organizations, Nadar as a visionary, believes in value creation, entrepreneurial and win–win relationship-driven culture, strong organizational growth based on the spirit of partnership and mixing aggressiveness with innovation. In recognition of his pioneering role in business and philanthropy, Nadar was awarded the Padma Bhushan by the Government of India. Keeping the leadership qualities of Nadar in the background, we shall now discuss leadership.

Introduction

Leadership is the process of influencing people to work hard to accomplish their organizational, departmental and individual goals. Leadership is what a leader does. It also means something that a leader does to a follower. Leading as a managerial function involves building commitment and enthusiasm among people so that they work willingly and effectively towards the task accomplishment. The success of leadership lies in the ability of the managers to make things happen in the way they wanted it to happen. Leadership involves the use of influence to get tasks accomplished through the group members. Since leading is one of the core managerial functions of the management, typically all managers should be leaders. The effectiveness of leadership usually depends on the relationship among the leaders (say, managers), followers (subordinates), and the circumstances involved.1 As leadership is a complex task, it needs to be developed through training, experience and analysis.

Power and influence are the terms closely associated with leadership. For instance, leaders need power to influence the activities of their group members. Here, power refers to the capability of people to influence or change the behaviour or action of members of group. Influence means any actions of the leaders that cause changes in the behaviour or attitude of an individual or group. Influence also means a kind of dynamic relationship prevailing among the people. Such influence must be multidimensional, non-coercive and reciprocal in nature. For instance, managers influence and also get influenced by the actions of their subordinates.

Definitions of Leadership

Influencing the activities of the group members is the primary focus of many definitions of leadership. We shall now look at a few definitions of leadership.

“Leadership is an influence relationship among leaders and followers who intend real changes and outcomes that reflect their shared purposes.2” —Richard L. Daft

“Leadership is the process of directing and influencing the task related activities of group members.”3 —James Stoner

“Leader is someone who can influence others and who has managerial authority.”4—Stephen P. Robbins

“Leadership is an attempt to use non-coercive influence to motivate individuals to accomplish some goals.”5 —James L. Gibson

“Leadership is the art or process of influencing people so that they will strive willingly and enthusiastically toward the achievement of group goals.”6 —Harold Koontz and Heinz Weihrich

We may define leadership as a process of influencing people in such a way that they willingly contribute to the accomplishment of intended goals.

Characteristics of Leadership

Even though there are differences in the style and approaches of leaders due to differences in their characteristics, the needs of followers and the organizational situation, the basic characteristics of leadership are broadly similar. They are as follows:

- Goal-based activity—Since leadership generally aims at influencing people towards the accomplishment of goals; it is a goal-based activity.

- Power-based activity—The power of the leader’s position has a definite influence on the employees. The greater the power, the greater the leader’s influence on followers.7

- Pervasive in nature—Leadership is needed at all levels of an organization. It cannot be confined to the top levels or to certain positions in the organization.

- Persuasive process—Leadership involves the process of persuading or inducing individuals or groups to pursue organizational goals and objectives. It does not typically involve the use of non-coercive methods to influence people

- Interactive process—Leadership is a dynamic and interactive process involving three dimensions, namely, the leader, the follower and the situation. Each dimension influences and gets influenced by the other dimensions.

Leadership vs. Management

Leadership is viewed as something different from management by many management experts.8 According to them, management works in the system whereas leadership works on the system.9 Generally, leadership can exist even for completely unorganized groups but managers need roles specified by organizational structure. In case of organizations, the typical role of managers in an organization is to promote stability, order and problem-solving ability all within the existing system and structure. In contrast, the leaders’ role is to encourage vision, change, improvements and creativity. However, leadership cannot be a substitute for management; rather, it is only a supplement. Managers’ job predominantly involves the maintenance of status quo in the organization. But leadership tends to question the status quo, so that the outdated and unproductive practices are questioned and replaced with challenging goals and tasks. In simple terms, “a manager takes care of where you are, a leader takes you to a new place.”10 Thus, good managers are essential for meeting the existing goals and objectives effectively while good leaders are important for keeping the organization moving forward.

To be effective, leaders of organizations should be proactive, creative, flexible, passionate, visionary, inspiring, courageous, innovative and experimental in nature. They should initiate changes and depend on personal power to lead others. As against this, successful managers usually need to be authoritative, analytical, rational, consulting, structured, persistence, tough-minded and stabilizing in nature. They normally adopt a problem-solving approach and use positional powers to manage others.

To be successful, managers must possess both managerial and leadership skills. Understandably, people who develop skills in leadership role and managerial functions will: (i) have long-term vision and remain futuristic (ii) look outwards towards the larger organization (iii) influence others beyond groups (iv) emphasize vision, values and motivation (v) be politically astute and (vi) think in terms of change and renewal.11

Process of Leadership

Leadership is viewed as a process by Jay Conger.12 According to him, this process typically consists of four steps. They are: (i) developing a strategic vision (ii) communicating the vision to others (iii) building trust among members and (iv) showing the ways and means to achieve the vision through role-modelling, empowerment and unconventional tactics. We shall now discuss them briefly.

- Developing a strategic vision—This stage in the leadership process involves the creation of vision for the organization. Through the formulation of vision, a leader decides what an organization wants to become. A leader’s vision helps in the establishment of a strong organizational identity. A well-formulated vision enables the organization to plan for its future and decide the long-term direction. It also indicates the company’s desire to achieve a specific business position.

- Communicating the vision to others—Once the vision is properly formulated, it becomes necessary for leaders to communicate it to the members of the organization. Since the vision is prepared in the present based on the past for the future, it typically acts as a bridge between the present and the future for an organization.

- Building trust among members—No vision can be established by coercion or diktat. Leaders need to use their persuasion skills and techniques to secure the cooperation and commitment of members to vision. Leaders can gain the trust and confidence of the members through their technical expertise, risk-taking attitude, self-sacrifice and unconventional behaviour. Generally, members adopt a vision and work towards it, if they believe that such vision serves the organizational as well as their own individual interests.

- Showing the ways and means to achieve the vision—Through role-modelling, empowerment and unconventional tactics, leaders can inspire members to work towards the fulfilment of the organizational vision. Leaders should establish motives and incentives for the members to share the vision and work in a unified manner towards the organizational success. A shared vision is capable of animating, inspiring and transforming purpose into action. Box 13.1 shows the leadership development initiatives of a private-sector organization.

Leadership Theories

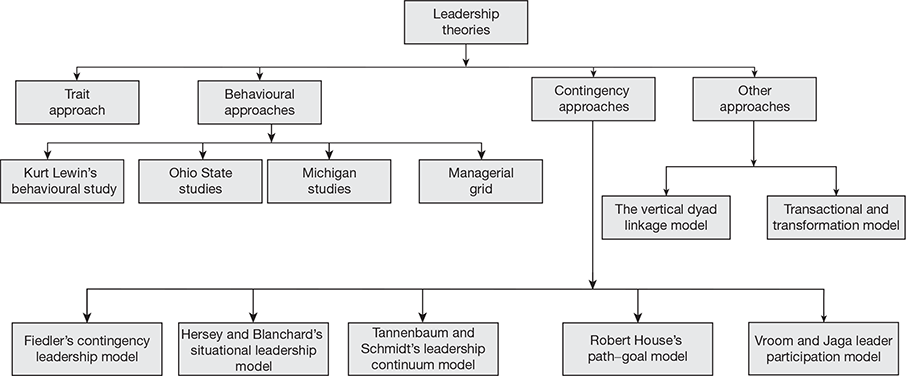

Many theoretical approaches are available to the study of leadership. As seen in Figure 13.1, some of the important theoretical approaches are: (i) trait approach (ii) behavioural approach, (iii) contingency approach and (iv) other approaches. We shall now discuss these approaches in detail.

Trait Approach

Traits are the distinguishing personal characteristics of a leader. They may also be defined as the recurring regularities or trends in a person’s behaviour. The trait approach to leadership was one of the first systematic efforts to study leadership. This approach is also called genetic approach as it assumes that leaders are born and not made.13 This approach is based on the assumption that great leaders possess certain innate qualities and characteristics that differentiate them from their followers. Trait approach is also called as great person theory. This theory also maintains that people behave in a particular way because of the strengths of the traits they possess. This theory believes leaders and non-leaders could be differentiated by a universal set of traits and characteristics. During the early 20th century, several researches focused on identifying those specific traits and characteristics.

Box 13.1

Leadership Development Initiatives at Wipro

Successful organizations develop high potential leaders to remain competitive in the market and grow over a long term. The success of any organization in developing leadership at different levels depends on its ability to make the leaders understand that their value lies not only in managing teams and organizational activities but also in inspiring others, developing purposeful goals, implementing strategic visions and fostering cultures of excellence. The leadership initiatives at Wipro are worth mentioning here.

The spirit of Wipro, which is the core of the organization, guides the actions of its leaders and their teams. The spirit of Wipro manifests itself in three important forms. They are: (i) intensity to win, (ii) act with sensitivity and (iii) unyielding integrity. The objectives of many leadership programmes at Wipro are to gear up the managers to take up the challenge of successfully heading large and strong teams. In this regard, Wipro has developed a unique competency framework called WIBGYOR, which stands for Wipro’s Career Bands Gives You Opportunities and Responsibilities. WIBGYOR defines the behavioural competencies that are to be demonstrated by organizational members in general and the leaders in particular. These competencies are usually defined role-wise and the members are evaluated on these competencies at the time of performance appraisal to stimulate role-based growth.59

After analysing the research studies conducted between 1904 and 1947, Ralph Stogdill14 identified the presence of eight traits in successful leaders. They are: (i) intelligence, (ii) persistence, (iii) initiative, (iv) self-confidence, (v) responsibility, (vi) insight, (vii) sociability and (viii) alertness. However, Stogdill maintained that leaders are not qualitatively different from their followers and a few characteristics such as intelligence, initiative, stress tolerance, etc. are modestly related to success. Generally, in these studies, people with exceptional follower performance, high status positions within an organization or salary levels that are higher than their peers were viewed as successful leaders.15

Though initial researches validated the perspectives of this approach, subsequent studies carried out in the mid-20th century questioned the fundamental premises that a specific set of traits defined leadership.16 Consequently, attempts were made to include the impact of situations and followers on leadership. The scope of trait approach was thus widened to include the interactions between leaders and the context, besides analysing the critical traits of leaders.

Behavioural Approach

While trait approach focuses on identifying the critical leadership traits, behavioural approach concentrates on identifying behaviours that differentiate effective leaders from non-effective leaders. The primary aim of the behavioural approach is to decide what behaviours are typically associated with successful leaders. The basic premises of this approach are: (i) the behaviour of effective leaders are different from that of less effective leaders and (ii) the behaviour of effective leaders will be the same or similar across all situations.17

While determining the behaviour of leaders, researchers generally focused on managerial aspects such as how the leaders communicate with their followers, how they do their tasks, how they delegate their tasks, and what do they do to motivate their subordinates. Behavioural approach to the study of leadership is vastly enriched by leader-behaviour studies such as the Kurt Lewin’s behavioural study, Ohio State studies, the Michigan studies and the managerial grid. We shall now discuss each one of them.

Kurt Lewin’s behavioural study—One of the earliest studies to identify the effect of leadership behaviour was carried out by a group of researchers led by Kurt Lewin in the 1930s. As a part of this study, different groups of children, all aged about 10 years, were exposed to three different kinds of leadership styles normally adopted by adults. These leadership styles were:

- Authoritarian or autocratic leadership style—In this case, leaders remain aloof and issue orders to the group members without consultation.

- Democratic leadership style—In this case, leaders constantly guide the activities of the group members and encourage their active participation.

- Laissez-faire style—This is also called “leave employee alone” style. In this case, leaders just provide knowledge to the group members. But they do not guide or direct the activities of the group members. Members are simply allowed to make and execute decisions without any follow-up by the leaders. They also avoid any participation in the activities of the group members.

The results of the study enabled researchers to claim that the leadership style has a direct impact on the group productivity and performance, group members’ behaviour and interpersonal relationship. For instance, group members under democratic leadership style have high work morale, friendly interpersonal relationship, high level of work quality and originality and less dependence on leaders. But their productivity will not be as high as that of the group under autocratic leadership style.

Under autocratic leadership style, group members exhibit aggressive and apathetic behaviour. They are defiant and blame each other for any failures. They also continuously seek the attention of their leader. Finally, under the laissez-faire leadership style, group members experience low level of satisfaction and low work morale and cooperation. Productivity and quality are lowest under the laissez-faire leadership style. In the final analysis, democratic leadership style emerged as the most successful leadership style in the study.18

The Ohio State studies—In the late 1940s, researchers at Ohio State University studied the subordinates’ perception of their leaders’ behaviour. In this regard, they developed and administered a specific questionnaire to people in both military and industrial settings to learn about their perceptions. Initially, the Ohio Studies identified more than a thousand dimensions or forms of leadership behaviour. But then they subsequently narrowed it to just two dimensions. As shown in Figure 13.2, these two dimensions are: (a) initiating structure behaviour and (b) consideration behaviour. Let’s discuss them briefly.

- Initiating structure behaviour—This behaviour dimension places importance on tasks and goals. In this form of behaviour, leaders clearly define their own role as well as their group members’ role in accomplishing the goals. Well-defined roles enable the subordinates to understand what is expected of them. Leaders also normally establish clear channels of communication and decide the specific methods for attaining group goals.19

- Consideration behaviour—In this kind, leaders’ work relationship with their subordinates is characterized by mutual trust, two-way communication and respect for group members. The leaders of this method recognize that individuals have needs and require relationships. This was also called relationship behaviour. Leaders of this behaviour category generally remained friendly, approachable and also helped the group members who experienced personal problems.

Figure 13.2

Ohio State Studies

The research results of the Ohio studies showed that the rates of employee turnover were lowest and employee satisfaction was highest under leaders who were high in consideration. In contrast, leaders who were high in initiating structure and low in consideration faced problems of high employee turnover and low employee satisfaction. According to this study, leaders who ranked high on both dimensions tend to influence the workforce to a higher level of satisfaction and performance. However, the weakness of this study is that it did not consider the influence of situational factors on leaders’ behaviour.

The University of Michigan studies—Almost during the same period as the Ohio studies were carried out, researchers at the University of Michigan were carrying out similar studies. These studies were carried out under the direction of Renis Likert.20 The primary purpose of these studies is to identify efficient leadership styles. They focused on two dimensions of leadership, i.e. production-centred leadership and employee-centred leadership. We shall now discuss them briefly.

- Production-centred leaders—These leaders focus fundamentally on the technical aspects of the job, setting rigid work standards, organizing tasks down to the last details, explaining work procedure and task accomplishment. They also firmly believe in the close supervision of their employees. Obviously, they view their employees as means and tools to accomplish the tasks. These leaders are also primarily concerned about the efficient completion of the job assignment.

- Employee-centred leaders—These leaders place more emphasis on developing interpersonal relations and cohesive work groups. They tend to take personal care and interest in the needs of the employees. They also encourage employees’ participation in goal-setting and decision-making process. Further, they recognize the individual differences among employees with regard to performance and behaviour. The primary concern of these leaders is on the well-being of the employees and their job satisfaction.

Researchers involved in the Michigan studies found that the employee-centred leaders were able to achieve higher level of productivity than the production-centred leaders. The study also showed that the most effective leaders were actually maintaining a supportive relationship with their employees. They were inclined more towards group decision making than individual decision making. They were also in favour of allowing their employees to set their performance goals to improve their commitment and motivation.21

Michigan and Ohio studies have a few similarities. For instance, both studies insisted that effective leader behaviour is primarily situational, i.e. leaders’ behaviour varied with the situation. Similarly, they emphasized on performance (for instance, production performance was considered in Ohio studies and goal performance in Michigan studies).

The managerial grid—The managerial grid was developed by Robert Blake and Jane Mouton.22 During the 1960s, they re-examined the two dimensions of leaderships identified by the Ohio and Michigan studies and came up with a two almost similar leadership behaviour dimensions. These two behaviour dimensions are: (i) concern for production and (ii) concern for people. However, the managerial grid is based on the assertion that one best leadership style exists. Managerial grid helps in evaluating the existing leadership styles of the managers and trains them to adopt ideal leadership behaviour.

The two dimensions of leadership behaviour namely, “concern for production” and “concern for people,” are typically measured through a questionnaire on a scale from 1 to 9. The scores for these two dimensions are plotted on a grid as shown in Figure 13.3. The horizontal axis in this grid represents concern for production whereas the vertical axis represents concern for people. Even though 81 combinations of concern for production and concern for people are possible, the managerial grid identifies five leadership styles only. These styles are: (i) impoverished at 1.1, (ii) authority compliance at 9.1, (iii) middle of the road at 5.5, (iv) country club at 1.9 and (v) team leader at 9.9. Let us now look at these leadership styles.

Figure 13.3

The Managerial Grid

- Impoverished leaders—These leaders put in minimum required efforts to retain their position or job in the organization. They are usually concerned more about their own well-being and survival in the organization than about the employees under their supervision. Further, these leaders normally have low concern for production as well as for people.

- Authority compliance leaders—The main focus of this category of leaders is to get work done through their employees. They usually tend to treat their people like machines. These leaders often exhibit autocratic behaviour while dealing with their employees. They normally have high concern for production and low concern for people. They care less for the problems of their people such as stress or conflict.

- Middle of the road leaders—These leaders tend to balance their concern for production and concern for people. They try to get work done by the employees even while maintaining their motivation and morale at satisfactory levels. The situation factors normally decide the attitude and style of these leaders. These leaders believe that adequate organizational performance is possible through fine balancing acts. However, such balancing acts are rather difficult on a long-term basis. Moreover, it is tough to maintain an equal concern for production and for people at the same time.

- Country club leaders—These leaders are most concerned with their employees’ well-being. They make sure that the needs and aspirations of the employees are adequately met and a friendly and affable environment exists within the organization. The fundamental belief of these leaders is that by satisfying the relationship needs of the employees, a positive work tempo and pleasant work ambiance can be established. However, the major weakness of this approach is that it fails to focus on the production concerns of the organization. Understandably, this approach can also lessen the overall capacity of the employees to accomplish or exceed the organizational goals and plans.23

- Team leaders—These leaders are viewed as ideal leaders by Blake and Mouton. According to them, interdependence through a “common stake” in organizational goals and plans can enhance the mutual trust, confidence and respect in relationship. The primary focus of this approach is on developing a sense of purpose and sense of accomplishment in both concern for production and concern for people. Box 13.2 shows the application of managerial grid in a private-sector business organization.

The managerial grid is viewed as an effective tool to identify and develop leadership qualities among managers. Managerial grid, especially the team leader model, has enabled many organizations to determine their multiphase training as well as development programmes required to achieve specific leadership behaviour. Since there is always scope for improvement in a leader’s behaviour and approach, it is difficult to attain ideal manager’s position and retain it.

Box 13.2

Nine Box Matrix for Leadership Differentiation at HUL

Organizations adopt leadership differentiation processes to classify leaders based on their performance. In this regard, they typically use techniques like performance reviews, leadership style assessments, assessments centres, cross-project assignments, etc. to clearly differentiate individual leaders with potential to meet the future leadership requirements of organizations. For instance, the multinational giant, Siemens, USA, adopted a global performance management process to achieve more accurate differentiation among employees with the aim of identifying future leaders for organizations. The leadership differentiation process of Hindustan Unilever Limited (HUL) is a case in point.

HUL makes use of the Nine Box matrix, namely, the managerial grid technique for identifying the future leaders of the company through leadership differentiation process. In HUL, every person is plotted in appropriate groups. For instance, all general managers are plotted together. Likewise, the executives belonging to similar categories of jobs are plotted together in the nine box matrixes. The purpose behind such exercises is to identify the higher performers who have the potential to go to the next level. In HUL, an employee should have completed a minimum of three years in the company before being included in the nine box matrix for leadership differentiation. In HUL, the Nine Box matrix not only measures the performance of managers but also their efficiency as leaders.60

Contingency or Situational Approaches

After extensive research on the trait and behavioural aspects of leadership, several researchers have come to the view that no one trait or style (behaviour) is common or effective to all situations. They also believe that the leadership style or behaviour differs from one situation to another. They have attempted to prove that the leadership effectiveness cannot be attributed to the leader’s personality alone. Consequently, they began to identify the factors in each situation that can influence the effectiveness of a specific leadership style.24 They also attempted to develop suitable leadership styles for specific situations. However, some researchers feel that it is easier for leaders to change the situation than to change their style.25 Research on leadership styles based on situations is categorized in contingency approach to leadership. The important contingency leadership theories are: (i) Fiedler’s contingency leadership model, (ii) Hersey and Blanchard’s situational leadership model, (iii) Tannenbaum and Schmidt’s leadership continuum model, (iv) Robert House’s path–goal model and (v) Vroom and Jaga leader participation model. We shall now discuss each of these models.

Fiedler’s contingency leadership model—According to Fred E. Fiedler who developed the contingency leadership model, the leadership style of a person reflects his or her personality. Such leadership style also remains basically constant. This model states that effective group performance depends on correctly matching the leader’s style and quantum of influence in the situation.26 Simply put, effectiveness of a group depends on the suitable match between the leader’s style and the demands of the situation. In this regard, Fiedler has advocated a two-step process. They are: (i) listing of the leadership styles that would be most effective for different situation and also the possible types of situations and (ii) identifying suitable combinations of leadership styles and situations.

The primary focus of this model is on determining whether a leadership style is task-oriented or relationship-oriented and also whether the situation suits the leadership style. To determine the nature of leadership style (whether it is task-oriented or relationship-oriented), Fiedler developed The Least-Preferred Co-worker (LPC) questionnaire and administered it to a group of employees. Least-preferred co-worker is a co-employee with whom a person (say, a colleague or superior) could work least well. The responses to LPC questionnaire were measured and averaged. Leaders who described their least-preferred co-worker in relatively mild and favourable manner would have high LPC scoring. This would indicate that these leaders have human relations orientation and adopt relationship-oriented style.

In contrast, leaders who described their least-preferred co-worker in an unfavourable manner would have low scores. This would indicate that these leaders adopt task-oriented leadership style. Through his model, Fiedler advocates that matching leader style to the situation can yield big dividends for the organization in the form of profit and efficiency. However, this model was criticized on the ground that it is tough for the leaders to change their style when the situational characteristics change.27

Hersey and Blanchard’s situational leadership model—The focus of this leadership model is on understanding the characteristics of the followers while deciding the appropriate leadership behaviour. In simple words, leaders adjust their style based on follower readiness to do the task in a given situation. Here, follower readiness refers to the ability, willingness or confidence levels of the followers to perform the specified tasks. According to this situational model, successful leadership practices are the outcome of interactions among three important dimensions. They are: (i) the quantum of guidance and direction provided by a leader, (ii) the amount of social and emotional leadership provided by a leader and (iii) task readiness of the followers. Based on the extent of guidance and direction required by the followers, a leader may respond to the situation on hand in any one of the following ways.28

- Delegating—This is a low task and low relationship style. The leader allows the group members to take responsibility for any task decisions. This style can be suitable when the followers have the capability, willingness, commitment and confidence to do the tasks entrusted. In this style, the task responsibility and control is with the leader, especially regarding when and how the leader should be involved. This style can work well when the followers’ readiness is high.

- Participating—This is a low task and high relationship style. Here, the leader focuses primarily on frank and open discussions with the employees and collective decisions on task planning and accomplishment. This style is preferred when the leaders have the ability, but not the willingness and confidence to successfully complete the tasks. This style is best when the followers’ readiness is low to moderate.

- Selling—This is a high task and high relationship style. This style is tried out when the followers lack adequate capability, but keep high commitment and willingness to do the task entrusted. Here, the leader just explains the task direction in an encouraging and persuasive manner. This style is most suitable when the followers’ readiness is moderate to high.

- Telling or coaching—This is a high task and low relationship style. Here, the leader defines the followers’ role, provides clear direction and also training, if necessary. They also extend personal, social and emotional support to them. Leaders tend to adopt this style when their followers are short on ability, willingness and confidence. This style can be appropriate when followers’ readiness is low.

According to this model, leaders should change their leadership styles as their followers change over time. This model also believes that when appropriate styles are adopted by the leaders, especially when the followers are in low-readiness situation, then these followers will grow in maturity and readiness over a period of time. However, adequate research has not been carried out on this model even though it remains intuitively appealing.29

Tannenbaum and Schmidt’s leadership continuum model—This model covers a range of leadership behaviours. According to this model, leadership behaviour or style could exist on a continuum (range) from boss-centred to subordinate-centred leadership. At one end of the continuum, a leader may take complete control of the situation by unilaterally making decisions and then just informing the subordinates (boss-centred leadership). At the other end of the continuum, the leader and subordinates collectively and collaboratively make decisions in a participative manner after clearly understanding the organizational constraints. Within these two extremes of behaviours, a leader may also exercise a variety of leadership pattern to include or exclude subordinates in the decision-making process.

The variety of leadership behaviour are: (i) leader sells the decision, (ii) leader presents the ideas and calls for questions, (iii) leader makes tentative or provisional decision and invites discussion for improvement or modification and (iv) leader just explains the situation and the problems. He/She then seeks suggestions and arrives at decisions (v) leader defines the parameters and limits and lets the subordinates make all the decisions and (vi) leader just defines the limits and permits the subordinates make the decision after identifying the problems and developing the options.30

A leader’s selection of a specific leadership pattern in a continuum is typically based on the nature and intensity of three forces. These forces are:

- Leader forces—Typically, these forces emerge as a result of a leader’s own personality and preferred behavioural style. A leader’s experience, expertise, values, knowledge, feeling of security and the degree of trust in the subordinates’ ability, influence their selection of specific leadership styles. Personality and behaviour are the major forces that drive the leaders to become autocratic or participative in their leadership style.

- Subordinate forces—These forces emerge as a consequence of the personality, behaviour and expectations of the subordinates towards their leader. These forces typically influence the followers’ preferred style for the leader. These forces influence the decisions of the leaders regarding the leadership styles. For instance, a highly participative leadership style can be tried by a leader when his followers are able, willing and motivated.

- Situational forces—These forces arise out of environmental variables like the organization, task, work group, etc. Specifically, the size, structure and climate of the organization, technology and goals, influence the selection of a specific leadership style by a leader. Further, the attitude of the superiors can also influence leadership style decisions of a leader. For instance, a low-level manager may prefer to follow the leadership style of their high-level managers.31

This model is viewed as another form of contingency approach to leadership as it also insists that the success of leadership depends on the match between the leader’s preferred style, subordinates’ expectation and behaviour and situational necessities. In any case, this model helps people to explore a range of possible leadership styles available.32 But this model is criticized for not considering the social aspects, while deciding the leadership styles. It has also failed to unambiguously attribute different behavioural effects to different leadership styles.33

Robert House’s path–goal model—The primary aim of the path–goal model is to find the right fit between leadership and situation. Through this theory, Robert House tries to explain how a leader’s behaviour influences the satisfaction and performance of the subordinates. This theory suggests that leaders are effective only when they enable their subordinates to accomplish their tasks. In this regard, a leader is supposed to adopt a suitable leadership behaviour, irrespective of their preferred traits and behaviour. The path–goal model recommends four distinct types of leader behaviours and suggests that the leaders can move back and forth from one type to another depending upon the subordinates and the environment. Research on the path–goal model suggests that a leader can try all these four styles under different circumstances.34 Let us now briefly discuss each of these four leadership behaviour.

- Directive leadership—In this style, leaders let the subordinates know what is expected of them. They also tend to provide precise guidance about what is to be done and how it should be done. They schedule the work to be done. They establish and communicate clear and definite performance standards to the subordinates. Then, they coordinate the activities of the subordinates. Importantly, they explain the role of the leaders to the group members in an unambiguous manner. When task objectives and assignments are unclear, then directive leadership can help in clarifying such task objectives and the likely rewards.35

- Supportive leadership—In this style, leaders adopt friendly and caring approach to the needs, status and well-being of the subordinates. These leaders make every effort to make the work environment pleasant and enjoyable. They also treat their subordinates as equals and treat them with due dignity. Supportive leadership can boost the confidence of subordinates by emphasizing individual abilities and providing customized assistance, especially when the subordinate’s confidence and self-belief is low.

- Participative leadership—In this style, subordinates are consulted by the leaders on work-related matters. Subordinates’ opinion, views, suggestions and ideas are given due consideration by the leaders when they make decisions. Participative leadership will be effective to clarify individual needs and identify suitable rewards, especially when performance incentives are inadequate.

- Achievement-oriented leadership—In this style, leaders adopt a task-oriented approach by setting challenging goals for their subordinates. These leaders normally display high confidence in the skill and ability of their subordinates in performing challenging tasks. They seek their subordinates to achieve excellence in performance. When the job does not have adequate task challenges, then achievement-oriented leadership can help in setting challenging goals and improving the performance aspiration of subordinates.

According to this model, it is possible for the leaders to alter their style or behaviour to suit the requirements of the situation. Generally, two situational factors influence the relationship between a leader behaviour and subordinate outcome. They are shown in Figure 13.4.

- Subordinates’ characteristics—A leader’s behaviour will be acceptable to the subordinates only to the extent that such behaviour acts as an immediate or future source of satisfaction to them. Subordinates’ characteristics, such as their ability, locus of control (degree to which a subordinate views the environment as systematically responding to his behaviour),36 needs and motives can influence a leader’s behaviour.

- Environmental forces—A leader’s behaviour can be motivational to the subordinates only to the extent that such behaviour makes their satisfaction dependent on their effective performance and other aspects of the work environment, including guidance, support and reward. Environment forces include the subordinates’ tasks, the primary work group and the formal authority system. 37

Figure 13.4

Path–Goal Model

Though the path–goal model is seen as improvement over the trait and behaviour models, the validity of the path–goal theory has not yet been determined.38 Occasional attempts to substantiate this model have achieved only mixed results.39

Vroom and Jaga leader participation model—According to this model, leaders are most effective only when the leadership style used by them best suits the problem being faced. This theory states that the degree of subordinates’ involvement in the decision-making process is a major variable in leader behaviour.40 This theory suggests that the leader’s choice for making decisions typically falls under three categories. They are:

- Authority decision—In this case, the decisions are made by the leaders and then communicated to the subordinates. Obviously the views and opinions of the subordinates or others may be obtained by the leaders without disclosing the problems.

- Consultative decision—In this case, the leaders obtain the views, advice and opinion of the subordinates while making decisions. Understandably, the decisions are made by the leaders and not by the subordinates. Consultative decision can be further classified into individual consultation and group consultation. In individual consultation, the leader discusses the problems with the subordinates individually while making decisions. In group consultation, the leader holds a group meeting for ascertaining the views of the members and making decisions.

- Group decision—In this case, the decisions are made by the subordinates themselves. The leaders may choose to adopt any one of the two styles. For instance, the leader may act as a facilitator by conducting the meeting, defining the problems and mentioning the limits within which the decisions are to be made. Leaders will not force their views or opinions on their subordinates and will encourage the subordinates to actively participate in the meeting and contribute to the decision-making process. In another form, leaders just let the group do everything, including problem diagnosis, alternatives (choice) development and decision making but within the limits prescribed by the leaders. Here, the leaders confine themselves to clarifying the subordinates’ queries and encouraging their participation.

A leader’s selection of a specific decision style is generally influenced by three vital factors. They are:

- Decision quality—This depends on the quality of source information or input, strength of the decision-making process and expertise of the decision maker.

- Decision acceptance—This refers to the importance of subordinates’ acceptance (of decisions) to the eventual success in the implementation of the decision.

- Decision time—This refers to the sufficiency of time available for making and implementing decisions.

The factors governing the decision style of the leaders can be classified into seven categories as follows: (i) decision significance, (ii) importance of commitment, (iii) leader expertise, (iv) likelihood of commitment, (v) group support for objectives, (vi) group expertise and (vii) team competence.41 Since each decision-making style has its advantages and disadvantages, it is imperative for the leaders to shift from one style to another depending upon the developments in the environment. This model enables managers to decide when they should make decisions and when they should let their subordinates make decisions.

Other Approaches to Leadership

In addition to the major approaches to leadership discussed, a few other approaches have also been developed. They are: (i) vertical dyad linkage model and (ii) transactional and transformation model. We shall now discuss these models briefly.

The vertical dyad linkage model—Dansereau and others developed this model based on the assumption that the leaders behave differently with different subordinates.42 The term “vertical dyad” in the model refers to the individual relationship that exists between the leader and the subordinate. In other words, this theory states that the leaders tend to develop some special kind of relationship with a few members. Understandably, leaders develop an “in-group” and “out-group” for themselves. The in-group members are more trusted and preferentially treated by the leaders. Since these members are viewed as best performers by the leaders, they get special assignments and privileges and enjoy better access to information. These members usually enjoy high exchange relationship with their leaders. In contrast, members of out-group are generally ignored and get fewer benefits. These members normally have low exchange relationship with their leaders.43

This theory has been found to be more useful in describing the relationship between the leaders and their subordinates.

Transactional and transformation model—This leadership model was first developed by James M. Burns and refined by Bernard Bass.44 According to this model, two different types of management activities are performed by leaders and each activity demands different types of skills on the part of the leaders. These two management activities are: (i) transactional leadership and (ii) transformational leadership. Let us now discuss them briefly.

- Transactional leadership—This kind of leadership is viewed as a traditional form of leadership. In this leadership kind, the leader–subordinate exchange primarily focuses on the accomplishment of pre-determined performance goals. Transactional leadership involves routing activities like allocation of tasks, making routine decisions, supervising subordinates’ performance and so on. In this kind of leadership, the exchange between the leader and the subordinates has four dimensions. They are: (i) contingent rewards including wage contracts, incentive for good performance and other recognitions, (ii) management by exception (active)—looking for performance deviations and rules violations and initiating corrective actions, (iii) management by exception (passive)—interventions only in the case of apparent performance failures and (iv) laissez-faire, avoiding decision and abdicating responsibility.45

- Transformational leadership—This kind of leadership requires the leaders to possess skills necessary for recognizing the need for change and introducing suitable course of action to achieve it. This leadership expects the leaders to influence the needs, values and beliefs of the subordinates in the desired manner. This model suggests three important ways to bring about changes in the values and beliefs of the subordinates. They are: (i) enhancing the subordinates’ awareness on the significance of their task and its accomplishment, (ii) letting subordinates be aware of the importance of achieving personal growth and development and (iii) motivating subordinates to give more importance to the organizational interest over that of their own personal interest.

The leader–subordinate exchange in transformational leadership has four dimensions. They are: (i) idealized influence—leaders behaving in a way that gets them admiration, respect and trust of the followers, (ii) inspirational motivation—leader’s behaviour builds enthusiasm and commitment among the subordinates, (iii) intellectual stimulation—leader’s behaviour challenges the subordinates to be creative and innovative and (iv) individualized consideration—leader’s behaviour enables the subordinates to reach their full potential.

According to Bass, transactional leaders are typically a hindrance to changes while transformational leaders are capable of achieving superior performance even in uncertain circumstances.46

Leadership and Organizational Life Cycle

In its evolution process, each organization goes through different stages and forms before it becomes matured. Each growth phase of an organization may require the managers to adopt different leadership styles. According to Clark, an organization typically goes through five phases and each phase requires the adoption of different leadership styles by the managers.47

In the first phase, for instance, the leaders are required to be highly individualistic, and innovative with high entrepreneurial spirit. This is primarily because this phase is often viewed as creativity phase as organizations mostly achieve growth through creativity.

In the second phase called the direction phase, leaders are expected to provide strong direction to the organizational members. Authority at this stage is largely centralized and members look to their leaders for direction and frequent guidance. At this stage, effective direction contributes to further growth of the organization.

In the third phase called delegation phase, leaders need to optimally delegate power to their subordinates so that the latter have adequate autonomy to perform their job efficiently. When the organization becomes large in size, delegation helps in faster decision making and better accountability at different levels. At this phase, effective delegation is largely responsible for the growth of the organization

In the fourth phase, organizations should seek to grow further through proper coordination. Understandably, this phase can be called coordination phase and the role of leaders is that of a “watch dog” as they assume the role of protector or guardian.

In the fifth phase, the participative approach of leadership facilitates the growth of the organization. In other words, organizations seek to grow through elaboration at this stage. Leaders should enhance their interpersonal skills and adopt team-oriented approach to achieve further organizational growth. Leaders should have to be more imaginative and ingenious in their approach.

In their further research on leadership style, Clarke and Bratt have identified four different leadership roles to be performed by managers during different phases of the organizational life cycle. These roles are: (i) the champion, who is the defender of a new business as it is fraught with numerous dangers, (ii) the tank commander, who carries the business forward to the next stages, (iii) the housekeeper, who keeps the business stable and balanced after it reaches the maturity stage and (iv) the lemon squeezer, who extracts the maximum out of the business after it shows sign of decline.

Recent Trends in Leadership Approaches

Even though many forms of leaderships are in existence, a few forms have recently gained importance due to their utility value to the managers in the present context. These leadership forms are: (i) ethical leadership, (ii) strategic leadership and (iii) cross-cultural leadership. We shall now discuss each of them.

Ethical Leadership

Ethics refers to the ethical principles that determine the behaviour of an individual or a group. The term ethics is an abstract concept and can be measured only through principles and practices adopted by the leaders in dealing with their subordinates. Of late, there is growing interest among management on ethical leadership. Organizations have begun to introduce high ethical standards for their managers to prevent any possible ethical misconduct and the consequent loss of organizational goodwill. Managers normally identify certain behaviour and motives like honesty, trustworthy, fairness and altruistic as representing ethical leadership. Value-based management, which means behaviour based on ethical principles and values, is a good formula for the long-term health and success of every organization. In fact, the practising of ethical values in management is an essential prerequisite for both individual success and organizational efficiency. However, when individuals practise ethical values within an organization, it does not mean that the entire organization is ethical. Only when the entire organization practices fairness and justice in a systematic way can it be called an ethical organization. The foundation of ethical organizations is mutual trust and respect.

A violation of ethical principles in decision making by an organization or its leaders can have a deep impact on its members’ life and character. A written statement of the policies and principles that guide the behaviour of all the persons is called the code of ethics. But the fact is that no amount of written rules can achieve ethical behaviour among the employees unless the organizational leaders conduct themselves in a fair, moral and legal manner. Ethical leadership is essential for creating an ethical workforce. The employees of an organization view their leaders as role models to determine their own behaviour. Indeed, those organizations where employees reported fair treatment by management showed proportionately less unethical behaviour.

Today, the survival and success of organizations in a globalized market depend more on the ethical standards adopted by them. In ethical organizations, people can trust one another to back up their words with action. These organizations often have contented employees and are usually identified by their high productivity and effectiveness compared to that of their competitors. We shall discuss the different types of ethics.

Types of ethics—Ethics can broadly be classified into three types, namely, descriptive ethics, normative ethics and interpersonal ethics.

- Descriptive ethics—It is mostly concerned with the justice and fairness of the process. It involves an empirical inquiry into the actual rules or standards of a particular group. It can also mean the understanding of the ethical reasoning process.48 For instance, a study on the ethical standards of business leaders in India can be an example of descriptive ethics.

- Normative ethics—It is primarily concerned with the fairness of the end result of any decision-making process. It is concerned largely with the possibility of justification. It shows whether something is good or bad, right or wrong. Normative ethics cares about what one really ought to do and it is determined by reasoning and moral argument.49

- Interpersonal ethics—It is mainly concerned with the fairness of interpersonal relationship between the leaders and their followers. It refers to the style of the managers in carrying out their day-to-day interactions with their subordinates. The manager may treat the employees either with honour and dignity or with disdain and disrespect.

Approaches to ethical issues in organizations—Though many leaders are interested in acting in an ethical manner, they often face dilemma in determining what constitutes ethical actions. For instance, organizational politics is viewed as an unethical act by many organizations, yet it is widespread in our country. Indeed, the difficulty surrounding ethics makes it hard to distinguish right from wrong.50 However, leaders can ensure that their policy satisfies as many persons as possible in the organization. Similarly, they should provide for the recognition of the rights of an individual while determining the ethical proportion of organizational polices. Velasquez et al.51 have provided a proposition for determining whether a particular policy or action is ethical or not.

- Utilitarian approach—In this approach, the managerial policy is based on the philosophy of utmost good for the greatest number of people. It evaluates the ethical quality of policies and practices in terms of their effects on the general well-being. For instance, decisions like lay-offs in a difficult situation for the organization are justified on the grounds that they benefit a majority of the employees.

- Approach based on rights—This approach is based on the principle that an organization should respect an individual’s dignity and rights. Each employee is entitled to be treated with due respect and be provided with safe working conditions, a reasonable and equitable pay system, and relevant and unbiased performance evaluation. An individual’s privacy and integrity should also be respected by the organization.

- Approach based on justice—The focus of this approach is on equal treatment, adoption of due procedure and consistency in application of policies and rules. The focal point of this approach is on fairness in ensuring a balance between the benefits and the burdens of the job, such as compensation and performance, compensation and job attendance, etc.

International business ethics—As a result of globalization, there has been a tremendous increase in the number of companies conducting business across national boundaries. Indeed, intense competition forces companies of different natures and sizes to enter global markets, in some cases with absolutely no knowledge on the diversity of business standards and practices in the host country (country of operation). Business leaders now have to learn how to adapt to diverse national cultures and socio–economic conditions, and new and diverse ways of communicating with and managing people.52

Guidelines for international business organizations on ethical issues—When the existing ethical standards of multinational companies are inadequate, these companies can adopt any one of the following guidelines to develop ethical standards for evaluating the decisions of their organizational members operating at global levels.

- Human rights obligation—This guideline is based on the fundamental human rights. The proponent of this guideline, Thomas Donaldson,53 advocates that organizations and their leaders have an obligation to recognize and respect certain rights as fundamental international rights. These rights are: the right to freedom of physical movement; the right to ownership of property; the right to freedom from torture; the right to a fair trial; the right to non-discriminatory treatment; the right to physical security; the right to freedom of speech and association; the right to minimal participation; the right to political participation; and the right to subsistence. Donaldson declares that each company is morally bound to discharge these fundamental rights, and any persistent failure to observe them would deprive the company of its moral right to exist.

- Welfare obligation—Based on moral considerations, Richard T. De George54 proposes a few guidelines for international organizations and their leaders with the twin aims of preventing damage and providing benefits to the host countries. These guidelines are:

- Multinational companies should desist from committing any intentional direct harm to the host countries.

- They should ensure that they create more good than harm for the host country as a result of their operations.

- They are morally bound to contribute to the growth and progress of the host country by their activities.

- They must see to it that their activities are, as far as possible, in compliance with the local practices and culture. They should also strive hard to respect the human rights of their employees in the host countries.

- They have a moral and legal responsibility to pay a fair share of taxes to the governments of these nations.

- They should work together with the local government in developing and maintaining institutions with a just and fair background.

- Justice obligation—It deals with the fairness of the activities of a multinational company in the host country. Leaders of multinationals have an obligation to help in the development of the host country, in addition to their business activity. Their organizations should be not only efficient but also responsible business houses. Foreign companies often attempt to avoid the payment of proper taxes by resorting to transfer pricing, which refers to the values assigned to raw materials and unfinished products that one subsidiary of the multinational company sells to another subsidiary in another country. Since pricing is done as an internal mechanism independent of market forces, companies tend to manipulate it to show profits in counties where taxes are low. Such manipulative practices must be avoided.

Strategic Leadership

Leadership literature earlier focused on the leadership roles performed by the supervisory- and middle-level managers. Of late, the focus has shifted to the strategic leadership roles performed by the top managerial executives and teams. Strategic leadership can be defined as “the complexities of both the organization and its environment and to lead change in the organization in order to achieve and maintain superior alignment between the organization and its environment.”55 Since strategic leadership clearly relates to the role of top management, managers who are a part of this leadership actually influence the overall effectiveness of large organizations.

To effectively discharge the strategic leadership functions, managers need to have a clear, complete and critical understanding of their organization. They should be familiar with the vision, mission, ethos, history, strengths and weaknesses of their organization. Strategic leaders must also be aware of the organization’s internal and external environment. They should also know the nature and kind of alignment existing between the organization and its environment. While making strategic decisions as a part of the strategic leadership, managers can adhere to certain guidelines like: (i) careful consideration of the long-term and short-term goals, objectives and priorities of the organization, (ii) evaluating the existing strengths and weaknesses, (iii) keeping the core competencies in focus, (iv) assessing the need for major changes in the strategies, (v) identifying the prospective strategies, (vi) assessing the possible outcomes of a strategy and (vii) choosing the appropriate strategy after wider consultation with other strategies.

Cross-cultural Leadership

Cultural values tend to influence and shape the perceptions, cognitions and preferences of organizational members and teams.56 Consequently, there will be wide differences in the behavioural norms of the members across cultures. It thus becomes essential for managers to adopt cross-cultural leadership (or shared leadership) and such leadership is widely prevalent in organizations with diverse cultural settings. The advancements in communication technology and transportation have vastly increased the cross-cultural interactions within organizations. The need for the development of cross-cultural leadership has arisen due to rapid social transformation, an enhanced access to education and increased labour mobility and the changing workforce profile of country. For instance, the proportion of women, religious minorities, physically challenged and socially backward people in the workforce has increased dramatically. This is a direct challenge for managers as they have to deal with culturally and racially diverse work groups. Thus, there is growing need among organizations to develop cross-cultural leadership among their managers. Many firms are now compelled to initiate new gender-specific and target-based policies to serve the interests of different sections of the employees.

The primary challenge of cultural leadership for managers is to motivate the organizational members of culturally different groups towards the accomplishment of valued goals by understanding and appealing to the shared knowledge of the culturally diverse groups.57

Leadership Succession Planning

A change in executive leadership at some point of time is unavoidable for an organization. It is also a critical and tough exercise for an organization to find the right replacement for those in the top levels of the management at the right time. An effective succession plan can facilitate the organization in being prepared for planned or unplanned absence of its top managers and also in guaranteeing stability in its business operations. The purpose of a management or leadership succession plan is to ensure that, to the extent possible, the firm has a sufficient number of competent managers to meet the future business needs. Succession planning is actually a process through which an organization plans for and appoints top-level executives. It usually requires suitable managers to fill the vacancies caused by retirement, promotion, death, resignation and transfer of the existing managers. By implementing a succession management programme that is transparent and equitable, an organization forms an environment for the employees to expand their skills in anticipation of future possibilities. This also enables a workplace to position itself to adequately face any situation that might arise in the organization on account of management changes.

Further, succession planning is also capable of reducing performance variations in key roles, reducing attrition among top performers, encouraging high internal recruitment and enhancing the motivation levels of managers. The concept of succession planning has gathered momentum in Indian companies. Many top companies have chalked out systematic plans for identifying and grooming talents, which would eventually take over the top positions in the company. For instance, a few years back, L&T, one of India’s leading engineering companies, declared the top 10 per cent of its executives as stars and developed fast-track career paths for them. In course of time, these executives replaced the senior managers when they retired.58

Need for Succession Planning

In a globalized economy, the scarcity of people qualified for important leadership positions has become one of the foremost challenges facing the management today. Companies are having an acute shortage of talent, especially at the top levels of the management. This is because the demand for able and experienced managers often exceeds their supply. There are several factors that have contributed to this situation. They are explained in the following paragraphs.

Growth of organizations—A typically growing organization will require additional leaders to fulfil its ambitious organizational goals and objectives. The expansion schemes of the companies and the tight labour market conditions may combine to create an acute shortfall in executive talent. This would in turn influence organizations to undertake succession programmes more seriously and on a priority basis.

Early retirements—Even though employees can remain in their jobs for a longer duration, especially in private firms, top managers are of late quitting the firms early to take up lucrative consultancy services. As a recent phenomenon, even those employees who are in their early- or mid-50s quit their job to take up career in other fields where they can make more money. These developments have further enhanced the importance of succession planning for an organization.

Coping with multiple competency requirements—Present-day organizations with a complex network and global presence are seeking to have executives with multiple competencies for the higher levels of management. For instance, companies are now looking for managers who can excel at collaboration and partnering, understand and handle vast ambiguities, and deal with global business issues. They should also be familiar with matters like business start-ups, mergers and acquisitions, management of change, the ability to manage new technology, and foreign assignments. Of course, these managers should possess these skills in addition to the conventional skills and knowledge, such as leadership skills, communication, behavioural skills and motivational skills. But, it is difficult for organizations to get a sufficient number of good managers with these qualities. Hence, organizations depend critically on succession planning to develop managers with complex skills and abilities.

Poaching—To deal with leadership scarcity, some organizations try to attract the managers of their rivals with attractive job offers. When the efforts of these organizations succeed, the organization losing the employee might face a tight situation, especially in the short run. To avoid such a predicament, it is necessary for organizations to develop and implement management succession plans.

Requisites for successful succession management—Organizations should understand clearly that succession planning cannot function in isolation and, in order to achieve success, it should be properly integrated with the corporate goals and plans. Similarly, it should get the full-fledged cooperation of all the stakeholders, namely, the trainer, the trainee manager, the management and the HR people. The following are the basic requirements in succession planning for developing leadership that delivers business results and assures stability:

- The succession planning programme should have the complete support and patronage of the top management.

- The management should forecast with maximum possible precision the skill requirements for the immediate and distant future.

- The organization should revise the list of jobs critical to it periodically and bring them under the succession planning programme.

- The organization should systematically identify the employees with potential managerial competence for developing their skills and knowledge.

- There should be a proper alignment of the HR strategy and the succession plans. While determining HR activities such as training and development, and performance evaluation, the succession plan requirements should also be considered.

- The knowledge, skills and abilities of the prospective employees must be developed on a sustained basis.

- A proper mechanism should be put in place to provide constant feedback to the potential successors on their performance and progress. There must also be a system for evaluating the efficiency of the trainers in succession planning.

- The organization should adopt a strategic and holistic approach towards succession planning and leadership development.

Box 13.3 shows the leadership succession initiatives at a large and reputed private industrial unit.

Impediments to Effective Succession Management

Organizations often fail to identify the factors undermining the success of their succession plans, and these factors eventually affect the efficiency of these programmes. It is hence essential for organizations to concentrate on the identification and elimination of factors that impede the effectiveness of succession planning. We shall now discuss the major impediments to succession planning process.

Box 13.3

Leadership Succession Initiatives at Reliance Industries Limited

Many organizations view leadership succession initiatives as an important strategy to sustain competitive advantages. Developing individuals for future leadership assignments is an ongoing and multifaceted activity in many organizations. Depending upon an organization’s specific needs, the management may develop its own customized succession management techniques and processes. Similarly, a management may employ different leadership development strategies for the different kinds of leadership roles in the company. RALP, the leadership development strategy of Reliance Group, is an interesting example.

Reliance Accelerated Leadership Programme (RALP) is an initiative of Reliance Industries Limited to create a strong leadership cadre that will supplement the pipeline for senior leadership roles likely to emerge in Reliance within the next 10 years. The purpose of RALP is to accelerate the development of young talent so that they become fit to take up leadership positions by their late 30s or early 40s, as the case may be. Participants of this programme will acquire different functional skills different. Since the primary focus of RALP is to get the requisite number of people ready for future leadership positions at the higher level, it focuses on training the participants across different functional and cross-functional domains with an accent on blended learning.61

Lack of criteria for the identification of the successor—Many organizations care little about developing clear and objective criteria for selecting the potential successor for filling the future positions. Many senior managers identify their successor through chance observation of people and their skills. An inaccurate identification can keep out the talented and deserving but less visible employees from the succession programme.

Presence of traditional replacement systems—In many organizations, the replacement planning process targets specific persons instead of identifying specific positions for succession planning. People-oriented succession planning often ends up with the identification of a few subordinates by the senior managers for inclusion in the succession planning. Instead, the organization should first identify the critical positions to be included in the succession planning. Then, it should develop a pool of high-potential candidates for inclusion in the planning process. Thus, a position-based replacement system is required for the success of the succession programme.

Improper diagnosis of development requirements—Often, organizations make wrong assessment of the skills requirements of potential successors. When the skills requirements are misjudged, it often leads to inaccurate selection of training and development techniques and performance evaluation methods. It is, therefore, essential for an organization to evolve scientific methods to identify the skills and knowledge requirements for its future positions and also the skill gaps of the trainee managers.

Inadequate focus on interpersonal skill requirements—On many occasions, organizations emphasize more on developing the technical skills and competencies of the future leaders and simply overlook their interpersonal and team- building skills. Consequently, the succession programmes pay no attention to leadership, motivational, communication and socialization skills of the participants. An organization should, therefore, develop a comprehensive succession programme by including both hard and soft skills components in the development programmes for its prospective future leaders.

Too little importance to lateral mobility—Quite often, organizations consider vertical mobility of the immediate subordinates to higher positions as the only option available in succession management. They simply ignore the prospects of lateral mobility, which considers other employees also for higher positions as an alternative in succession planning. Any narrow approach towards succession management would reduce the scope of succession planning in the organization. Hence, managements should include lateral mobility also as a part of succession management strategy.

Lack of sufficient and timely sharing of feedback—The absence of availability of feedback on the current performance and future assignments may drive a potential successor out of the organization. When prospective employees remain ignorant of what their management plans for their future, they may tend to quit the organization in search of better prospects elsewhere. Hence, it becomes important for the organization to ensure that the information on career plans concerning the employees is shared with them without any delay.

Lack of follow-up action—In many organizations, succession plans often remain in the plan stage and in paper form. These organizations lack the sustained enthusiasm and motivation required to follow-up the plans with necessary actions. In some organizations, the management simply fails to take succession management to its logical end, which is posting the identified and trained successors to the vacant positions. This occurs when the management changes its preference for the identified position and dumps the person groomed for that position through the succession planning process.

Absence of managerial initiative and support—The critical prerequisite for the success of any succession management programme is the active support and constant encouragement from the top management. Many organizations do not provide the importance that it deserves in the strategic planning. This is because the management is concerned more with its immediate future and short-term goals. It is important for managements to realize the benefits of succession management and they should strive to support this concept on a sustained basis.

Insecurity of the boss—Managers often feel threatened when succession issues are discussed with them. They view the move as the beginning of the end of their career with the organization. In such a situation, an insecure boss may display disinterest and even apathy in sharing his/her skills and knowledge with the potential successor. The top management should enlighten the managers about the purpose and intentions of succession planning and dispel any apprehensions that they may have about the whole programme.

Summary

- Leadership is the process of influencing people in such a way that they willingly contribute to the accomplishment of intended goals.

- There are four steps in the process of leadership. viz., (i) developing a strategic vision, (ii) communicating the vision to others, (iii) building trust among members and (iv) showing the ways and means to achieve the vision through role-modelling.

- The important leadership approaches are: (i) trait approach, (ii) behavioural approach, (iii) contingency approach and (iv) other approaches.

- The trait approach is based on the assumption that great leaders possess certain innate qualities and characteristics that differentiate them from their followers.