CHAPTER 14

Motivation and Morale

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Understand the meaning and characteristics of motivation

- Explain the importance of motivation

- Enumerate the forms of motivation

- Define the approaches to motivation

- List the factors influencing the motivational process

- Learn the steps of the motivational process

- Discuss the different content theories of motivation

- Explain the various process theories of motivation

- Understand McGregor’s theory X and theory Y

- Present an overview of Ouchi’s theory Z

- Understand the meaning and process of employee engagement

India’s Inspirational Managers

Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw is the chairman and managing director of Biocon, India’s largest biotech company. She is a first generation entrepreneur with over 36 years experience in biotechnology and industrial enzymes. She started Biocon in 1978. Within a year of its inception, Biocon became the first Indian company to manufacture and export enzymes to the USA and Europe. She spearheaded its growth from an industrial enzymes manufacturing company to a fully-integrated bio-pharmaceutical company through her single-minded determination, hard work, self-belief and self-motivation. She firmly believes that to create a great organization, the top leadership has to create a sense of ownership and excitement for its own people. According to her, the best way to motivate people is to make them feel that their organization is investing in their future. She also firmly believes in treating employees with respect and also respecting, recognizing and rewarding every individual’s contribution to the organizational growth. She has been included in Time magazine’s list of 100 most influential people and Forbes magazine’s list of 100 most powerful women of 2012. Kiran’s beliefs and values set the tone for discussion on motivation and morale in this chapter.

Introduction

Motivation is simply the process of encouraging employees to voluntarily give their best in the job so that the performance goals are achieved effectively. It is a drive that moves people to do what they do. Motivation involves identifying and influencing people’s behaviour in a specific direction. It actually works with the individuals’ desire, energy and determination and stimulates them to realize the predetermined goals. For instance, an employee in his job may decide to work as hard as possible or work as little as possible, depending upon his level of motivation. Generally, people’s desire for money, success, job satisfaction, recognition and team work can be used sensibly for motivating them. Motivating employees is important as lack of employee motivation can affect the organization’s initiatives and individuals’ performance.

Motivation is a challenging task for the managers as it arises from within persons and normally differs for each person.1 Since every person has different sets of needs and goals, it is essential to identify those needs and also the appropriate motivational techniques that fulfil them. Employees’ needs in organizations can broadly be classified as physiological needs, safety needs, belongingness needs, esteem needs and self-actualization needs.

Motivation, which is derived from the word “motive” (meaning needs or drives within individual), can be classified into intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation usually comes from inside an individual without any external rewards. Satisfaction in the successful completion of a work is an example of intrinsic motivation. In contrast, extrinsic motivation usually comes from outside an individual. In this case, rewards are independent of the job. They provide satisfaction that the job itself may not provide. Increased pay and promotion are example of extrinsic motivation.

Definitions of Motivation

Fulfilment of goals through willing and sustained cooperation from the employees is the essence of many definitions of motivation. We shall now look at a few definitions.

“Motivation is the willingness to exert high levels of effort to reach organizational goals, conditioned by the effort’s ability to satisfy some individual need.”—Stephen P. Robbins2

“Motivation is a decision-making process, through which the individual chooses the desired outcomes and sets in motion the behaviour appropriate to acquiring them.”—Huczynsk and Buchanan3

“Motivation refers to the forces either within or external to a person that arouse enthusiasm and persistence to pursue a certain course of action.”—Richard L. Daft1

“Motivation refers to forces that energize, direct and sustain a person’s efforts toward attaining a goal.”—Bateman and Snell4

We may define motivation as forces that originate internally or externally of individuals and drive them to voluntarily choose a course of action that produces a desired outcome.

Characteristics of Motivation

The essential characteristics of motivation are:

- Motivation is a psychological drive that forces individuals to act in a specific manner.

- Motivation is a complex and goal-directed behaviour. It aims at fulfilling the organizational and individual goals in the most desired manner.

- Presence of unfulfilled needs and wants is an important prerequisite for motivation.

- Motivation is a continuous process. This is because the fulfilment of one set of needs usually gives rise to another set of needs in a person.

- Motivation must always be comprehensive. As such, partial motivation is not achievable since needs are interrelated.

- Motivation is a situation-based and highly dynamic phenomenon. This is because the needs of individuals keep changing depending upon the trends and developments in the environment. The changed needs and drive may call for changes in the motivational techniques and tools.

- Motivation can be both internal and external to the individuals depending upon their needs, wants and the overall environment.

- Motivation is influenced by a variety of forces and pressures arising from an individual’s socio–cultural environment like family, social group, culture and value system.

- Motivation must always have a positive effect on employee behaviour and performance.

Importance of Motivation

Keeping a motivated and vibrant workforce is essential for organizations to succeed in today’s intensely competitive business environment. However, it is the most difficult task for managers because what motivates the employees changes constantly. Therefore the managers need to continuously motivate their people to get the best out of them and to retain them in the firm for a long duration. We shall now see the importance of motivation in detail.

- Motivation is an important tool to get people work hard in their job and for effective fulfilment of organizational goals and plans. Organizations can achieve high level of performance, productivity and quality through their motivated workforce. Certainly, workplace motivation infuses positive energy into the work environment.5

- It enables organizations to achieve the willing cooperation and voluntary support of the employees for its work methods, policies, programmes and practices. Employees may be more receptive to changes initiated by their management due to the goodwill and mutual trust generated by motivation.

- Motivation can keep employee absenteeism at lower levels in organizations by encouraging the employees to come to work regularly. When employees are dissatisfied they will suffer from low motivation and try to abstain from their duty. They may also quit their job if they are not properly motivated. Motivation thus ensures workforce stability.

- Motivation facilitates the maintenance of cordiality in the employer–employee relations within organizations. When employee needs are fulfilled, they develop a sense of loyalty. Indeed, motivated employees can understand their management better and avoid confrontations with it.

- Motivation enables organizations to build a positive image among the general public and more specifically in the labour market. Motivated employees contribute positively to any organizational initiatives that aim at building goodwill.

- Motivation, morale and job satisfaction are interrelated. Therefore, high employee motivation naturally boosts employee morale and increases job satisfaction.6 Morale is an employee’s attitude towards his or her job, superiors and the organization.

Forms of Employee Motivation

Motivation is usually associated with the unsatisfied needs of the employees. The nature of employee needs drives managers to choose a specific form of motivation. The motivation can be broadly be classified into intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation. We shall now discuss these two types of motivation.

Intrinsic Motivation

Intrinsic motivation refers to the drive or desire that arises from within an individual to do something or accomplish certain goals. Intrinsic motivation may simply be defined as “what people do without external inducement.”7 In organizations, intrinsic motivation emerges from an employee’s internal feelings. Individuals’ personal interest, desire, pleasure, satisfaction, fulfilment, etc. act as drives to internally motivate them. Intrinsically motivated employees will seek reward in the form of enjoyment, interest or satisfaction in work. It is generally stated that intrinsic motivation has better and more enduring results than extrinsic motivation.8 Experts on motivation feel that motivation from extrinsic sources is just complementary and additive to intrinsic source-based motivation.9 Factors that promote intrinsic motivation in individuals are: (i) challenge, (ii) curiosity, (iii) cooperation, (iv) control, (v) competition, (vi) recognition and (vii) fantasy.7 We shall now discuss each of them briefly.

- Challenge—Individuals are intrinsically motivated when they do personally meaningful tasks that present reasonable (intermediate) level of difficulty.

- Curiosity—Individuals’ eagerness to know the outcome of the activity performed by them.

- Cooperation—Satisfaction obtained by individuals through the help rendered to others in their goal accomplishment initiatives.

- Control—Individuals get satisfaction when their basic desire to exercise control over what happens to them are fulfilled.

- Competition—Satisfaction derived by individuals when they find their performance positive and superior in comparison to that of others. Competition is a powerful group-level intrinsic motivator.10

- Recognition—Satisfaction obtained by individuals when they receive recognition and appreciation for their achievements. It is capable of motivating both individuals and groups in organizations.

- Fantasy—Satisfaction received by individuals through their sheer imagination of situations and objectives that may not exist in reality.

It is to be noted that intrinsic motivation never means that an individual will not look for any external rewards for their accomplishments. It actually indicates to the management that external rewards alone are not sufficient to produce desired behaviour among employees.

Extrinsic Motivation

When the drive to do something or accomplish certain goals comes from outside of an individual, it is called extrinsic motivation. When external reasons influence a person’s behaviour, it is called external motivation. External factors influence employees’ needs and their behaviours. Pay raise, material rewards, promotion, praise, recognition, social approval, time off, special assignments and status are a few examples of extrinsic motivational factors. Work-linked extrinsic motivators are capable of dominating the intrinsic motivator to the end that intrinsic motivation simply disappears.11 The different kinds of motivational practices of a reputed power company are presented in Box 14.1.

Extrinsic motivation is often linked to the term engagement. The actual feeling of being motivated is often called employee engagement.12 This feeling enables employees to put their best efforts to the work (motivated behaviour). Engagement may also be described as a response or consequence linked to behaviour.13 The engagement can be classified into positive engagement and negative engagement. When appreciation, monetary reward or any other pleasant consequences follow the desired behaviour of the motivated employees, it is called positive engagement. The purpose of positive engagement is to encourage the desired behaviour and ensure its continuance in the future. As against this, when unpleasant outcomes like nagging and reprimands are stopped, removed or avoided as a consequence to desired behaviour, it is called negative reinforcement. These kinds of reinforcement convince the employees to do better in their job so that they can have the unpleasant condition removed from their work environment.

The total motivation can be greater only when the intrinsic and extrinsic motivations are high.14 In other words, the total motivation is likely to be lower if intrinsic motivation is low and extrinsic motivation is high and vice-versa.

Box 14.1

Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivational Exercises at Larsen & Toubro (L&T) Power

As a part of its motivational strategies, L&T Power develops the entrepreneurial skills of its workforce by enabling and empowering them to take appropriate risks. It encourages employee participation by inviting suggestions and opinions. It offers competitive compensation and rewards to motivate and retain the talented workforce. As a part of its intrinsic motivational strategies, it provides challenging, interesting and motivating assignments to its people that offer them a sense of professional fulfilment. This company also offers its employees freedom at work, unmatched leadership and the opportunity to grow at a rapid pace.

Besides the usual motivational practices, some of the L&T group companies offer fun-based innovative motivational activities like playing instruments, singing and dancing to its employees. For instance, this company provides music lessons to its employees through its online music academy. It also ensures that its employees participate in webcerts’ (online concerts), with willing employees logging on at the same time, and playing or singing. It also conducts dancing classes for its employees through a choreographer throughout the year. It also offers quizzing and a “management” film festival.85

Approaches to Motivation

As seen in Figure 14.1, the major approaches to enhancing employee motivation are compensation approach, job design approach,15 organizational culture approach and workplace relationship approach. We shall now discuss them briefly.

Compensation Approach

Compensation approach attempts to offer extrinsic motivation to employees while job design approach looks to increase their intrinsic motivation. Compensation approach of motivation is typically divided into direct compensation and indirect compensation. Direct compensation includes basic pay and variable pay, such as profit sharing, gain sharing and equity plans. Indirect compensation includes the benefits enjoyed by the employees but paid by the organization. Canteen facility and transport facility are a few examples of indirect compensation.

Figure 14.1

Approaches to Motivation

Besides the base salary, an organization also offers productivity-linked wage incentives to motive employees and enhance their performance. Wage incentives is any form of performance-based financial and/or non-financial rewards payable to attract, retain and motivate the best talents without any permanent financial commitment for the organization. Wage incentive plans are typically classified into three categories. They are individual incentive schemes, group incentive schemes and organization-wide incentive schemes.

Individual incentive schemes—Organizations adopt individual incentive programmes when the performance of each employee can be measured with a fair amount of accuracy. Usually, a portion of the employee’s pay is decided as a function of his/her performance. The aim of individual incentive programmes is to enhance motivation, efficiency, commitment, involvement and personal satisfaction of the employees. Without doubt, there is a direct and specific link between employee performance and earnings and, this link can be used to enhance productivity.16

Group incentive schemes—Organizations offer group incentive schemes for their employees to avoid the problems of interpersonal rivalry. Similarly, when the individual job performance cannot be measured with a fair amount of accuracy, organizations may opt for group incentive schemes. Many jobs in modern organizations require collective efforts from many persons. In such a situation, it becomes necessary for the organizations to offer group incentive programmes to accomplish the organizational and performance goals.

The essence of group incentive is gain sharing by the members through cost reduction measures. The two major factors influencing the group incentive scheme decisions are the size of the group and the nature of the activities. In any group incentive scheme, the total bonus payable to a group is determined on the basis of its overall performance.

Organization-wide incentive plans—Through organization-wide incentive plans, an organization aims at motivating all its employees to work hard both for the organization and for their own interests. The incentives available to the employees under organization-wide plans normally depend upon the overall performance of the organization for a specific period. The primary aim of this method is to develop employees’ unity, cooperation and eventually an ownership interest in the organization.

Job Design Approach

The primary purpose of a job design is to increase an organization’s ability to meet its objectives effectively through its motivated workforce. Job design intends to offer intrinsic motivation to its employees. The job design strategies that offer intrinsic motivation to employees include job enrichment, self-managing teams, job rotation, job reengineering, job enlargement, participative management, peer performance review and high performance work design. We shall now discuss the job design strategies briefly.

Job enrichment—Job enrichment refers to the development of work practices that challenge and motivate the employees to perform better. It often results in achieving desired improvements in productivity, safety of work, quality of products/services and job satisfaction.

Self-managing teams—Teams that are usually entrusted with the overall responsibility for the accomplishment of work or goal are called self-managing teams. They enjoy autonomy in decision making on matters involving when and how the work is done.

Job rotation—Job rotation refers to moving employees from one job to another in a predetermined way. This enables an employee to perform different roles and gain exposure to the techniques and challenges of doing several jobs.

Job reengineering—Job reengineering is the process of streamlining jobs in the form of combining a few jobs into one, redistributing the tasks among various jobs and reallocating the resources. It also involves reconsideration of the methods of job performance, physical layouts and performance standards.

Job enlargement—Job enlargement transforms the jobs to include more and/ or different tasks. Its basic aim is to make the job more attractive by increasing the operations performed by a person in that job.

Participative management—Participative management means allowing employees to play a greater part in the decision-making process.17 It has been found to be useful in improving the quality of work life, job enrichment, quality circles, total quality management and empowerment.

Peer performance review—Peer review is a performance evaluation technique adopted by an organization in which the employees in the same rank rate one another.

High performance work design—Developing a high performance work design is also considered as a strategy for job enrichment. Effective work groups are created in an organization through this technique to achieve a high level of performance.18

Organizational Culture Approach

The culture of an organization has a direct impact on the motivational levels of the organization. Corporate philosophy, leadership strategies, corporate goals and organizational setting typically determine the culture of an organization. Culture influences the way employees evaluate ideas and act on them.

Generally, employees associated with an organizational culture that promotes teamwork, collaboration, support and encouragement are likely to be better motivated. As against this, employees linked to an organizational culture that advocates centralization, dependence and close guidance are likely to be less motivated.

Workplace Relationship Approach

The nature and type of relationship existing between management and employees can significantly influence the motivational levels of an organization. In organizations where labour–management relationship is free of tension, conflict and distrust, employees are likely to be better motivated. When relationships are strained, employees are likely to lose faith in the management’s words and deeds. They will then remain less motivated. Poor superior–subordinate relationship has been found to be a major cause of low motivation in organizations.19 An open communication system can ensure that the actions of the managers are properly understood and interpreted by the employees. This can in turn help the managers to motivate their employees better and create a positive attitude in them. The motivational practices of an India-based Fortune 500 company are presented in Box 14.2.

Factors Influencing Work Motivation

Several researches have been carried out by psychologists to understand the reasons behind the different responses from organizational members to identical motivational measures. According to Michael G. Aamodt,20 four factors that are responsible for the differences in employee responses to the motivational measures of organizations are: personality, self-esteem, an intrinsic motivation tendency and need for achievement. We shall now discuss each of them briefly.

Personality—Researchers have found strong and consistent relationship existing between personality characteristics and performance motivation.21 For instance, the five dimensions of personality, i.e. openness to experience, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness and stability are strongly and logically related to different types of work motivation in different degrees. Research has indicated that stable, conscientious, disagreeable, and extrovert individuals have the highest level of motivation.22

Self-esteem—This is the degree to which people view themselves as valuable and worthy. Generally, individuals with high self-esteem are likely to be more motivated than those with low self-esteem.23 Employees who have a positive and good feeling about themselves are generally better motivated to do well in their job than those who have a negative feeling of themselves.

Box 14.2

Motivational Strategies at ONGC

The HR vision of ONGC, namely, “To build and nurture a world-class human capital for leadership in energy business,” provides clear direction to the HR department in its endeavour to develop effective motivational strategies. In fact, the HR policies of this company aim at developing a highly motivated, vibrant and self-driven team. This company has a reward and recognition scheme, a grievance handling scheme and a suggestion scheme to keep its employees motivated. It also has several incentive schemes to enhance the motivation and productivity of its employees. A few of these schemes are: (i) productivity honorarium scheme, (ii) job incentive, (iii) quarterly incentive, (iv) reserve establishment honorarium, (v) roll out of succession planning model for identified key positions and (vi) group incentives for cohesive team working, with a view to enhance productivity. Since this company strongly feels that motivation plays a pivotal role in HR development, it has in-built systems to recognize and reward its employees periodically.86

An intrinsic motivation tendency—Employees who incline more towards intrinsic motivation are more likely to persist in tough and challenging situations. In contrast, employees with extrinsic motivational orientation tend to give up early in their initiatives. Simply put, intrinsically motivated persons normally persist with their motivated behaviour for relatively longer periods than those who are more extrinsically motivated. Intrinsic motivation is thus associated with greater performance, more perseverance, creativity and higher level of satisfaction when compared to extrinsic motivation.24

Need for achievement—The need for achievement is possessed by all people in different degrees.25 Individuals who rate themselves high in achievement motivation are likely to work harder and more persistently than those who are low in achievement motivation. People who begin to believe in their ability to achieve are more likely to do so than those who expect to fail.26

Motivational Process

The word, motivation, which originates from the Latin word, movere, meaning “to move” is actually a process. The crucial role of managers in any motivational process is that of identifying the needs important to the employees, conditioning their behaviour and facilitating the fulfilment of identified needs and organizational goals. As Figure 14.2 shows, the motivational process of individuals typically includes steps like: (i) experiencing unsatisfied needs, (ii) searching for ways and means to satisfy needs, (iii) selection of goal-directed behaviour, (iv) implementation of the selected behaviour and (v) experiencing rewards or punishments.27 Let us now briefly discuss the different stages in the motivational process.

Experiencing Unsatisfied Needs

A need is something that remains to be fulfilled for an individual. It is also an internal state that makes some outcome more attractive. The unmet needs of a person act as drive or desire to attain motivated behaviour. Understandably, motivation is possible only when a person has one or more important but unsatisfied needs. Thus, the presence of strong needs is an essential prerequisite for the success of motivational process.

Figure 14.2

Steps in the Motivational Process

Searching for Ways to Satisfy Needs

It is but natural for the persons with needs to find ways and means to satisfy those needs. In fact, the unsatisfied needs are the driving force within individuals that propel them to desired behaviour or specific action. Each unsatisfied need is capable of producing a variety of behaviours, actions and goals in people. For instance, when an employee feels that his promotion is overdue, he may decide to either demand the management to sanction it or put in additional efforts in the job hoping to get that promotion or search for a new career befitting his knowledge, experience and ability.

Selection of Goal-directed Behaviour

Once individuals decide on their way of satisfying the needs, they choose a specific course of action and display a goal-directed behaviour. Unsatisfied needs are capable of activating, directing and sustaining the goal-directed behaviour of individuals. In the example of the employee whose promotion is overdue, if the employee decides to pursue the second option of working hard to earn his promotion, he will begin to exhibit appropriate behaviour necessary to accomplish the goals.

Implementation of Selected Behaviour

This stage involves the execution of the predetermined course of action and exhibition of appropriate behaviour. At this stage, an individual consciously enacts a specific goal-directed response (behaviour) in an expected situation.28 In the example of the employee whose promotion is overdue, these behaviours may include among others working long hours, exceeding performance targets, improving the relationship with superiors, etc.

Experiencing Rewards or Punishments

The outcome of any motivational process will be reward or punishment for an individual. When the motivational process eventually leads to the satisfaction of an individual’s targeted needs, it becomes a positive and rewarding experience for that individual. The rewarding experience indicates to the individuals that their behaviour was appropriate and can be repeated in the future. In contrast, if the needs of the individuals are not satisfied despite their best efforts, then it becomes an unproductive and punishing experience for them. In such situation, they need to have a relook at their needs, plans and behaviours.

Theories of Motivation

Motivational experts hold different views on what motivates the employees in their job. These different views have led to the development of multiple theories on motivation. Each theory advocates its own approach for effective motivation of people. The results of these theories are only suggestive and not conclusive. Broadly, the motivational theories are classified into two categories, i.e. content theories and process theories.29 Figure 14.3 shows the theories of motivation.

The content theories focus on the employees’ personal needs that they wish to satisfy through work. They focus on the basic needs that decide how people behave. They also focus on the characteristics in the work environment that facilitate the need fulfilment. In contrast, the process theories explain how various variables jointly influence the amount of efforts put in by the employees. They place emphasis on how human behaviour is initiated, sustained and extinguished.30 Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory, David McClelland’s acquired needs theory and Herzberg’s two-factor theory are a few examples of content theories. Equity theory, expectancy theory, social cognitive theory and goal-setting theory are some of the process theories. We shall now discuss the content-based motivational theories in detail.

Content Theories

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs theory

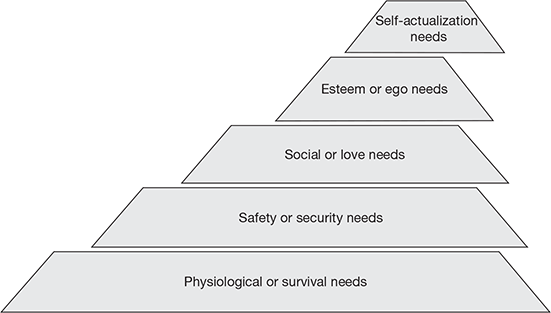

The hierarchy of needs theory proposed by Abraham Maslow in 1943 is one of the well-known theories of motivation. According to Maslow,31 human needs are hierarchical in nature. This need hierarchy has five stages indicating five needs. As seen in Figure 14.4, these needs are physiological needs, safety needs, social needs, esteem needs and self-actualization needs. The bottom-most needs in the hierarchy are usually survival (physiological) and safety needs. The topmost needs are self-esteem and achievement needs. Social needs are placed in the middle of the hierarchy. As per Maslow, when one set of needs are fulfilled, the individuals move to the next need as the satisfied need does not motivate them any longer. We shall now look at a brief explanation of each of these needs.

Physiological or survival needs—These needs usually include the need for basic necessities of life such as food, water, cloth, shelter, sleep and other physical requirements. As long as these needs remain unfulfilled for a person, the other higher order needs cannot motivate him/her. This is because the fulfilment of these lowest-level needs is essential for people to continue living. Organizations usually fulfil these basic needs of employees through the payment of basic salary and wages.

Safety or security needs—Once the basic physiological needs are adequately satisfied, the need for physical safety and job security arises for people. Here, physical safety refers to the need to be free from physical dangers such as bodily injuries and emotional harms such as psychological problems. Job security refers to the need to be free from the danger of losing one’s job and the resultant loss of food, cloth, shelter, etc. Safety and security needs thus include physical security, job security, order, stability, structure and freedom from fear, chaos and anxiety.32 Pensions and fringe benefits are the instruments available to organizations to fulfil the safety needs of the employees.

Social or love needs—Once safety and security needs are relatively well-satisfied, social needs become the dominant need for people. In this stage, people look to satisfy their need for love, friendship, affection, acceptance and the sense of belonging. Social needs are generally viewed as powerful motivators of human behaviour in organizations.33 Social or love needs primarily include an individual’s desire to be in the company of others. Socializing with co-workers, supervisors, customers and others in the organization enables the employees to fulfil their social or love needs.

Figure 14.4

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Theory

Esteem or ego needs—When the primary needs comprising physiological, safety and social needs are satisfied, the secondary needs such as esteem or ego needs become the predominant motivators of people. Esteem needs are generally classified into internal and external esteem. People satisfy their internal esteem (also called self-esteem) needs by acquiring competence, strength, confidence, mastery, freedom and independence. They satisfy their external esteem (also called esteem of others) needs by gaining prestige, status, dignity, glory, dominance, importance, recognition, appreciation and attention of others. Organizations may provide recognition, increased responsibilities, promotion to enable the employees to fulfil their esteem needs.

Self-actualization needs—These needs are the highest needs in the Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. They include a person’s need to grow and realise his or her full potential in life. Self-actualization is an open-ended need category as it is connected with the need “to become more and more what one is to become everything one is capable of becoming.”34 In other words, it is to achieve what one is capable of achieving and thus attaining self-fulfilment. In organizations, presence of opportunities for training, growth, advancement and creativity can facilitate the fulfilment of self-actualization needs of employees.

According to Maslow, people satisfy their needs in an ascending order by moving from one level to another in the hierarchy only after they substantially satisfy the needs of that level. He has described that the hierarchy may function in a different ascending order for some individual but for majority, it follows the order developed by him.35 Let us now evaluate Maslow’s need hierarchy theory.

Strengths of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory—Maslow’s needs theory became one of the most influential concepts in behavioural studies. We shall now see the strengths of the hierarchy of needs theory.

- Maslow’s need hierarchy is viewed as a simple and straightforward analysis of human motivation with human needs forming the basis for analysis.This theory has found wide acceptance among the practising managers for its logical explanation and easy-to-understand format.

- The emphasis of Maslow is in studying the healthiest and happy personalities when understanding the nature, needs and operations of the people. This is in contrast to many other personality theories that focus largely on the perspectives of maladjusted personalities.36

- Maslow has maintained a reasonably sensible and realistic view of the human nature. He has insisted that the process of self-actualization cannot occur automatically as it requires initiatives, desires and efforts on the part of the individuals.37

Weaknesses of hierarchy of needs theory—Even though Maslow’s theory is a widely acclaimed personality theory, it has quite a few weaknesses. We shall now discuss these weaknesses briefly.

- Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory is criticized on the ground that its major concepts are not supported by any empirical evidence. Moreover, very few researches have been carried out to test the validity of the theory.38

- This theory is also faulted for its assumption that the needs are satisfied in order or sequence only. In reality, higher order needs like self-actualization need not wait till the lower order needs like physiological needs are fulfilled. For instance, self-actualization needs may take precedence over physiological or security needs in some people in certain situations.

- Needs theory has also been criticized for the methodology adopted by Maslow for developing the concepts. For instance, he had finalized the characteristics of self-actualized individuals based on the biographies and writings of 21 people whom he stated as being self-actualized. This subjective judgment on self-actualization and self-actualizers cannot be accepted as a scientific fact.

- Another criticism against this theory is on its culture bias. Maslow’s theory is viewed as a western-oriented concept. This is because self-actualization is predominantly an individualized western concept and this may not be the case in non-western cultures.39 Further, the role and relevance of culture as a differentiator and determinant of need priority is not adequately recognized by this theory. For instance, the employees of European countries may feel that their esteem needs are better satisfied than their social and security needs, perhaps due to their cultural factors.

Herzberg’s Two–factor Theory

Frederick Herzberg, an American psychologist, developed the motivation-hygiene theory. This theory, popularly known as the two-factor theory, is also called satisfier–dissatisfier theory. The aim of Herzberg’s study is to know the problems of human motivation at work and find an answer to the question what do employees want from their job? Herzberg conducted a survey among 200 engineers and accountants to know when they felt exceptionally good or bad about their jobs. The responses were used to determine the events (factors) responsible for job satisfaction (good feeling) and job dissatisfaction (bad feeling). He eventually identified several important but different determinants for job satisfaction and job dissatisfaction.

Herzberg described the determinants of job satisfaction as “motivators” and those that prevent job dissatisfaction as “maintenance” or “hygiene” factors. Since the basic assumption of this theory is that two separate factors are responsible for job satisfaction and job dissatisfaction, it came to be known as the two-factor theory. Table 14.1 shows the factors responsible for the motivation and maintenance of employees in organizations.

According to Herzberg, the absence of maintenance factors results in job dissatisfaction. But the presence of maintenance factors does not automatically lead to job satisfaction because different kinds of factors are needed to provide job satisfaction. This is because job satisfaction and job dissatisfaction are not opposite of each other. They are in reality concerned with two different kinds of needs of employees. To put it differently, absence of job satisfaction cannot be considered as job dissatisfaction but as no job satisfaction only.

The two-factor theory presents four possible scenarios for organizations. They are as follows:

- In the first scenario, when both the motivation and maintenance factors are high in jobs, then employees will have higher motivation to work well and fewer complaints about work environment.

- In the second instance, when motivation factors are high and maintenance factors are low in jobs, then employees will have higher motivation but many complaints about work environment.

- In the third scenario, when the motivation factors are low and maintenance factors are high in jobs then employees will have lower motivation to work well but fewer complaints about the work environment.

- In the fourth scenario, when both motivation factors and maintenance factors are low in jobs, then employees will have low motivation as well as many complaints about the work environment.

Table 14.1 Factors Responsible for the Motivation and Maintenance of Employees

Figure 14.5 shows the motivation and maintenance factors of Herzberg’s two-factor theory.

According to this theory, motivational factors are more important of the two factors. Motivational factors have more enduring and effective impact on employees than those factors that prevent job dissatisfaction.40 Further, motivational factors directly affect the employees’ motivational drive leading to better employee engagement, higher productivity and enhanced job satisfaction. In its absence, employees are de-motivated to work efficiently. We shall now evaluate the two-factor theory.

Strengths of the two-factor theory—The two-factor theory advocated by Herzberg has the following strengths:

- Although Herzberg’s theory has been replicated many times in the past, the original results still hold true even today. Herzberg’s description of motivation and maintenance factors enable managements to gain deep insight into the factors that motivate the employees and those that retain them.41

- The two-factor theory has been appreciated for clearly making the management responsible for providing adequate motivators or hygiene to the employees through company policies, interpersonal relations, working condition etc.

Figure 14.5

Motivation and Maintenance Factors of Herzberg’s Two-factor Theory

Even though the Herzberg’s theory has been acclaimed as one of the most influential theories on human behaviour at work, it has a few important weaknesses. We shall look at them now.

- Herzberg’s theory has been criticized for the confusion in the classification of factors into motivational and maintenance factors. For instance, pay has got an almost equal rating as a motivational factor and as a maintenance factor from the employees involved in the study.42

- This theory is faulted for not considering the role of individual differences such as age, education, gender, sex, social status, experience and occupation in deciding the classification of motivational and maintenance factors.

- Herzberg has been questioned especially for the methodology adopted by him in the research work. The questionnaire techniques used by him are capable of prejudicing the results.43

- The two-factor theory has been criticized for ignoring the influence of situational variables in classifying the factors. Herzberg’s description of money as a mere maintenance factor and not a motivator for employees cannot always be true. This is because the role of money as a maintenance or motivational factor is decided more by the situation than by any other factors.

ERG Theory

Clayton P. Alderfer developed the ERG theory along the lines of Maslow’s hierarchy theory but with a few differences. He classified the human needs under three major categories, instead of Maslow’s five.44 These three need categories are: (i) existence needs, (ii) relatedness needs and (iii) growth needs. Let us discuss these needs briefly.

- Existence needs—It covers all forms of material and psychological desires of people. It includes all of the first and second level basic needs (physiological and safety needs) mentioned by Maslow.

- Relatedness needs—It involves the need for maintaining satisfactory relationship with other people in the organization. It focuses on the recognition, achievement and relationship needs of the people. It is similar to a part of Maslow’s third and fourth level needs (social and “esteem of others” needs).

- Growth levels—It refers to personal growth, creativity, competence and self-development needs of the people. It is similar to the fourth and fifth level needs (internal esteem and self-actualization needs) of Maslow.

According to Alderfer, people’s needs are not satisfied in any order. Different types of needs can be active at the same time. In other words, higher needs of a person need not wait for the lower needs to be fully or mostly satisfied before they become active. Alderfer introduced a frustration-regression principle as a part of his ERG theory.

According to ERG theory, Even if the lower-level needs are already satisfied, people will once again focus on these needs when their efforts to satisfy the higher-level needs are frustrated. For instance, if a person fails to fulfil his growth or relatedness needs, he will tend to over-satisfy his existence needs by making a lot of money.45 This theory thus assumes that people freely move up and down the need hierarchy depending upon the time, situation and expediency.

McClelland’s Acquired Needs Theory

American psychologist David McClelland developed the acquired needs theory. According to this theory, certain kinds of needs are learned or acquired during the life time of an individual. The three needs of such kind are: (i) need for achievement (nAch), (ii) need for affiliation (nAff) and (iii) need for power (nPow). People are usually driven by these three needs irrespective of their gender or culture. This theory insists that people are not born with these needs but learn them through life experiences.46 Let us now discuss these needs briefly.

- Need for achievement (nAch)—This is the desire to achieve, succeed and excel in challenging jobs. Persons with this need normally take up responsibility for finding solutions to difficult problems, set moderately tough goals and often get feedback on their progress and success. They do not attach importance for praise or rewards. This is because they generally consider the accomplishment of task itself as a reward. Most often, they prefer to work alone. People with need for achievement usually like to surpass others in competitive performance.

- Need for affiliation (nAff)—This is the desire to be friendly with others. Enjoying team work, giving importance for interpersonal relationship, avoiding conflict, showing desire to be liked by others, and reducing the level of uncertainty are a few examples of need for affiliation. People with this need normally prefer collaboration over competition. They are averse to high risk or uncertain situation. They tend to go along with the group and get influenced by the group behaviour.

- Need for power (nPow)—This is the need to influence and eventually control the behaviour of others. It involves making others behave in a way one wishes. Such people want to acquire authority over others and be responsible for them. Needs to win arguments, successful persuasion, etc. are examples of need for power. People with this need normally enjoy competition and triumphs. They like to protect and promote their status and recognition.

According to McClelland, people with high need for achievement display liking for tasks or jobs that are entrepreneurial and innovative in nature. People with need for affiliation are usually good at the job of integrating people (such as HR management). They achieve success in coordinating the activities of different people and departments.47 People with high need for power usually succeed in getting to the top positions in the organizational hierarchy. This need is closely associated with how people view or deal with their success and failure. For instance, fear of failure (and the resultant erosion of authority) may motivate some people with the need for power to succeed in their goals. In rare instances, fear of success (and the resultant loss of privacy) can also act as motivating factors.48

Evaluation of acquired needs theory—McClelland and his team developed the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT), a projective psychological personality test, for measuring the individuals’ level of need for achievement, affiliation and power. Participants of this test are shown a series of ambiguous pictures. Then they are asked to develop their own imaginary but spontaneous stories about each picture shown. According to McClelland, the participants, in all probability, will project their own needs through these stories. Based on the results, appropriate schemes may be drawn up for motivating the employees. It can also be used for determining the types of jobs for which an employee might be well-suited. However, it has a few major limitations and they are:

- The projective psychological personality test used by McClelland is criticized as being unscientific.

- The basic assumption of this theory—that the acquisition of motives or needs usually happens at the childhood of a person and is not prone to easy or frequent changes—is being questioned.49 Researchers have also questioned the wisdom of this theory that the needs are permanently acquired.50

Process Theories

Unlike the content theories that focus on people’s needs that cause certain behaviour, the process theories (also called goal theories) primarily focus on the process of motivation. Content theories attempt to find answers to questions like what motivates people while process theories focus on questions like how to motivate? We shall now look at the process theories.

Equity Theory

Equity theory was developed in 1965 by Stacy Adam. The essence of this theory is that people expect social justice in the distribution of rewards for the work done by them. According to this theory, job satisfaction and performance of employees depend upon the degree to which they perceive fairness and equity in their pay and promotion. The level of equity or fairness is decided by employees by comparing their efforts and rewards with others in the organization.

Equity theory states that people seek certain outcome in exchange for their inputs or contributions. The input may refer to employee’s efforts, experience, seniority, knowledge, skill, intelligence, etc. The outcome may include, among others, pay, promotion, benefits, praise, recognition, improved status and superior’s approval. Typically, most exchanges require a multiple of inputs as well as outcomes. This is quite similar to buying or selling of commodities.

According to Adam, the state of equity exists in an employee when he perceives that his ratio of efforts to rewards is equivalent to the ratio of other employees. This can be expressed though a simple expression:

In such comparison, when the ratios are found to be greater or lesser, the employee may perceive a state of injustice. For instance, when a person with higher qualifications and experience receives the same or less salary than another with lesser qualifications and experience, the employee may perceive inequality. Generally, the perception of such inequality may force (motivate) a person to bring equity and restore balance.51 Individuals normally adopt any one or more of the following methods to reduce their perceived inequality. They are:52

- Modifying the input to match the outcome. For instance, an underpaid employee may decide to work less or an overpaid employee may decide to work more to ensure equality.

- Modifying the outcome to match the input. For instance, a less paid person may demand more pay to match the efforts put in by him.

- Distorting perception happens when change in input or outcome is not possible. In such cases, people may tend to perceive the situation as per their convenience. For instance, when there is no equality in the rewards, an employee may distort the perceived rewards of others to make it equal to his own reward. For instance, an overpaid employee may believe and justify that his inputs are more than the underpaid employees of the same cadre. Similarly, employees may also tend to perceive a better status for their job than what it is actually.

- Quitting is the last option of employees to bring equality in efforts and rewards. This happens when all other options to achieve equality are not successful. The purpose of quitting is to find alternate jobs that are better in input–outcome ratio.

Evaluation of equity theory—Equity theory’s insistence on the need to treat people fairly and equally has received wide approval among managers. It enables managers to gain insight into employees’ perception of pay and other benefits. This theory rightfully insists that managers should consider the employee perception seriously as equity is more of a perceived phenomenon. It highlights the importance of comparison in the work situation and identification of reference persons.49 It also emphasizes the need to treat employees equally in unique ways. However, the equity theory has a few weaknesses. They are as follows:

- Researchers feel that it is difficult to practice equity theory because managers may not know exactly who the reference groups of employees are for their input–outcome comparison.53

- This theory has also been questioned for its assumption that overpayment of rewards (outcome) leads to the perception of inequality. This is because employees are rarely informed about overpayment to them. Moreover, employees tend to change their perceptions of equality to justify their overpayment.49

Victor Vroom’s Expectancy Model of Motivation

Expectancy model was developed by Victor Vroom in 1964. This theory is fundamentally based on a few assumptions such as: (i) individuals join an organization with clear expectations of their needs, motivation and environment, (ii) individual behaviour is usually their conscious decision, (iii) individuals seek to fulfil different goals and needs through their organization and (iv) individuals like to choose among the alternatives in order to maximise their outcome. This expectancy theory is based on the simple equation:

Here, expectancy refers to the probability perceived by a person that applying a given amount of effort will lead to a specific level of performance.54 It indicates the confidence level of an individual on the outcome of efforts. High levels of efforts and persistence are usually the result of high expectancy. An individual’s capability and experience and access to resources are the major determinants of his expectancy level.

Instrumentality refers to an individual’s estimate of probability that a given level of achieved task performance will lead to a particular outcome. People would like to perform at a high level only when they believe that such performances are the “ways and means” to the desired ends like monetary benefits, job security, promotion, etc. When an employee believes that a good performance will get him an increase in salary or promotion, the instrumentality will have high value. In contrast, if an employee perceives no correlation between good performance and pay or promotion, then the instrumentality will have low or no value.55

Valence refers to the worth of an outcome as perceived by an individual. When an individual attaches high value to the outcome, he would have greater motivation to perform at higher levels.

The motivation equation explains that the tendency of a person to act in a specific way depends on the strength of his expectation of the outcome (reward) of his effort and the attractiveness of such outcome to him. In other words, people are generally motivated when they think that they will be rewarded if they complete the task and such rewards for the task are worth the effort. The essence of this theory is that people can be motivated to work harder only when they perceive that better performance will get them better rewards like the accomplishment of career goals and aspirations.

Expectancy theory focuses on the three-way relationship. They are: relationship between efforts and performance, relationship between performance and reward and relationship between reward and individual goal fulfilment (level of satisfaction). Newsom identified “Nine Cs” as important for expectancy theory. They are: challenges, criteria, compensation, capability, confidence, credibility, consistency, cost and communication.56

Evaluation of Vroom’s theory—Several researches have supported the different elements of this theory. The strength of this theory is that it provides a process of cognitive variables that disclose the individual differences in work motivation.55 The assumption of this theory that employees are rational people whose decisions are guided by perceptions and probability of estimate makes it significantly different from several other theories in which unmet needs are the determining factors.

However, the major limitation of this theory is that in practice people rarely make decisions in such a calculating and complex manner.57 This theory has also been questioned for its claim that people are highly rational and objective in their decisions.

Porter and Lawler’s Motivational Model

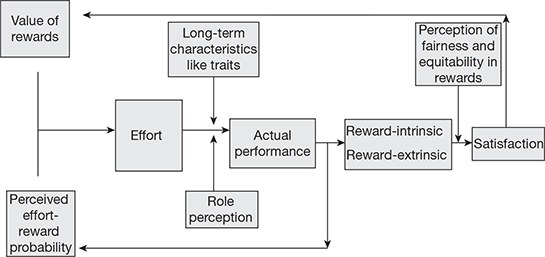

Porter and Lawler’s model (1968) is one of the complete models of motivation. This theory is based on the expectancy model developed earlier by Victor Vroom. Authors of this model have established a different kind of relationship between employee satisfaction and performance based on Vroom’s expectancy model. According to this model, when the rewards available to an individual are sufficient, he/she will then exert high level of performance that will lead to satisfaction. This is against the conventional thinking of “satisfaction leading to high level of performance.”

As shown in Figure 14.6, the amount of efforts (the energy spent to do a task) put in by a person in a job depends on his/her perception of the likely reward from the work, the probability of getting such rewards and the perceived energy levels required for the performance of such job. Further, the actual performance (accomplishment on task) in the job is influenced by an individual’s long-term characteristics, such as abilities and traits and also by his/her role perceptions (the type of efforts required for effective job performance as perceived by the individual).

The actual performance, in turn, leads to rewards. The reward for performance can be classified into two categories, i.e. intrinsic rewards and extrinsic rewards. Positive feeling, satisfaction and sense of achievement experienced by a person are examples of intrinsic rewards. Pay rise, better working conditions, improved status, etc. are examples of extrinsic rewards.

When the reward for performance is seen as fair and equitable by the individual, it leads to satisfaction. Lastly, the extent of satisfaction experienced by the individual tends to influence the future value of the reward for performance. Based on the extent to which performance leads to rewards, the perceived effort and reward probability (a perception whether differential rewards are based on differential efforts) is increased.58 The past performance and/or accomplishment of an individual can influence his/her perception relating to this effort–reward probability.

Finally, to make their motivational programmes more effective and result-oriented, managers should ensure that they: (i) recognize the individual differences among the employees, (ii) match people to job (right job for right people), (iii) utilize appropriate, specific and time-bound goals, (iv) make people believe that their goals are achievable, (v) ensure that the rewards are individual-specific, (vi) make sure that the rewards are performance-oriented, (vii) make employees perceive that the reward systems are fair and just, (viii) pay adequate importance for money as a motivator (ix) make people believe that the organization has genuine concern for their growth and well-being and (x) give necessary importance for non-monetary motivations such as recognition and appreciation.59

Figure 14.6

Motivational Model of Porter and Lawler87

Evaluation of Porter and Lawler’s motivational model—Porter and Lawler’s model is considered to be a complete model of motivation. It moves beyond the narrow concept of “motivational force” to the wider concept of “performance as a whole.” In fact, this is the first model that has directly studied the relationship between satisfaction and performance.60

The versions of Vroom and Lawler are found to be valid in several testing done in rationalized organizations.61 This motivational model succeeded in explaining most of the motivated behaviour, if not all.

This model clearly tells the managers that motivation is not simply a cause–effect factor. Instead, it requires them to carefully evaluate their reward structure, maintain good organizational structure and integrate effort–performance–satisfaction system into the whole system of management. This model however suffers from a few weaknesses. They are as follows:

- The effort–performance–satisfaction link is more difficult to be achieved at the team and organizational levels. This is because many other factors, other than employees own efforts, may also significantly influence the performance.62

- Porter–Lawler motivational model is viewed as a more complex motivational theory than most other theories on motivation.

- Similar to Vroom’s expectancy model, this model is also criticized on the ground that people may not be inclined to undertake a cumbersome exercise to make decisions.

Goal-setting Theory

Goal-setting theory was described by Edwin Locke and Gary Latham in 1968. This theory is based on the simple premises that a person’s intention to work towards a goal is an important source of motivation. The steps involved in goal-setting are: (i) setting the goals, (ii) getting goal commitment and (iii) providing support elements like resources, action plans, feedback, etc. According to this theory, managers can increase the motivational levels of the employees by formulating specific, tough goals that are acceptable to them. Managers should then provide regular and timely feedback that helps employees track their own progress towards goal attainment. In this regard, Locke has identified four parts of goal-setting theory. They are as follows:63

- Goal specificity—When goals are clear, specific and unambiguous, they will increase the motivational levels of the people. In other words, specific goals are more captivating than generalized goals. For instance, “visit your customer once in a week” is a more specific goal for a sales person than saying “do your best” to improve sales performance.

- Goal difficulty—Hard and ambitious goals are capable of providing more motivation to people than easy goals. This is because easy goals do not present any challenge to the employees in their work. The tough, but achievable, goals require employees to stretch their limits (in terms of talents and skills) to accomplish them.

- Goal acceptance—Prior to allocating tough and challenging goals, managers must ascertain the readiness and commitment of the employees to take up such types of goals. The best way to increase employee commitment to goal accomplishment is to involve them in the goal-setting process.

- Feedback—Constant feedback to employees on their progress in goal-related performance is an important way of increasing performance. Such feedback will enable employees to identify the performance gap (difference between actual performance and expected performance), if any, in a timely manner.

Evaluation of goal-setting theory—The major merit of this theory is that it offers good understanding of the goal the employees are to achieve and rewards available to them for successful goal completion. The researches done on goal-setting theory have shown that this theory is capable of improving cost control, quality control and the satisfaction levels of the workers.64 Further, researches on theories such as goal-setting have enabled organizations to shape job design programmes in a number of areas of work in the past two decades.65 Management techniques such as management by objectives (MBO) developed by Peter Drucker are consistent with the goal-setting theory. The popularity of MBO is a certain indicator of the success of the goal-setting theory.

However, this theory has an important weakness. The efficacy of goal-setting is mostly studied in simulated situations in laboratory setting and this obviously raises questions about its validity in actual situation.66

Reinforcement Theory

Reinforcement theory (also called behaviour modification theory) was developed by the Harvard psychologist, B. F. Skinner. Reinforcement may be explained as something that causes certain behaviour to be repeated. According to this theory, behaviour is simply a function of its consequences. The crux of this theory is that employees’ on-the-job behaviour can be modified through suitable and timely use of immediate rewards or punishments. For instance, the behaviour that gets rewarded is most likely to be repeated while the behaviour that gets punished is less likely to be repeated. Different forms of reinforcements can be used for different behaviour. The four important forms of reinforcements are: (i) positive reinforcements, (ii) negative reinforcement, (iii) punishment and (iv) extinction. We shall now briefly discuss each one of them.

- Positive reinforcements—These reinforce the desired behaviour. For instance, providing a reward; offering social recognition; giving positive feedback; praising the employees for certain behaviour such as reporting on time, doing extra work, well-execution of tasks; etc. are positive reinforcements. The aim of providing such pleasant and rewarding reinforcements is to enhance the chances of the desired behaviour happening again.

- Negative reinforcements—These strengthen the desirable behaviour by eliminating the undesirable situation or tasks. Here, an individual acts to avoid or escape something that is not pleasant. This is also called avoidance learning. For example, avoiding a noisy environment is a negative reinforcer, while achieving a noiseless or peaceful environment is a positive reinforcer. If an employee who gets repeatedly criticised by the supervisor for being late to office begins to come on time just to escape from reprimands, it is a negative reinforcement.

- Punishment—This is nothing but the undesired consequences of undesired behaviour. Punishment typically follows an undesired behaviour. The aim of any punishment is to lessen the chances of occurrence of negative behaviour. When an employee is sternly warned for his underperformance, then the expectation is that the negative outcome (severe warning) will discourage that person from repeating the undesirable behaviour (underperformance).

- Extinction—This relates to the removal of positive reward, where the positive reward will no longer be available to the employee. Extinction may involve the suspension of pay rise, increments, bonuses, praise, etc. The idea behind extinction is that any behaviour that is not positively reinforced is likely to be discontinued in the future.

Since the purpose of any reinforcement is to make the employees learn certain desired behaviour and leave certain undesired behaviour as quickly as possible, the timing of reinforcement becomes important. The reinforcement schedule normally includes: (i) continuous reinforcement and (ii) partial reinforcement. In continuous reinforcement, every incidence of the desired behaviour is reinforced. Companies usually prefer continuous reinforcement, for it enables the employees to connect their behaviour with the desired reward. When cash or reward points are given to sales people for every successful sales deal made, it is called continuous reinforcement.

In partial reinforcement schedule, only some occurrences of the desired behaviour are reinforced and not all. Partial reinforcement is further classified into the following:

- Fixed interval schedules—When employees are rewarded at particular time intervals, it is called fixed interval reinforcement (example, annual bonus).

- Fixed ratio schedule—When employees are rewarded after a specified number of desired behaviour or action (example, piece rate wage system).

- Variable interval schedule—When employees are rewarded in a random and unpredictable manner, it is known as variable-interval reinforcement (example, instant rewards to employees for good performance at surprise inspections).

- Variable ratio schedule—When employees are rewarded after unplanned or random number of desired behaviour (example, rewarding an employee, say, after five to ten instances of desired action).

Evaluation of reinforcement theory—The results of researches in reinforcement theory aimed at behaviour modification among employees have proved to be encouraging. Reinforcement programmes that reward the target behaviour are found to be successful in motivating the employees and increasing productivity.67

However, this theory has been criticized for a few reasons. For instance, this theory overstates the importance of extrinsic motivation for employees but in practice employees tend to get more satisfaction through intrinsic factors. Further, negative reinforcement, especially extinction, is not viewed as a good strategy to motivate the person for several reasons, such as the following:

- It may discourage undesirable behaviour but it cannot lead to desired actions.

- It may create ill-feeling and hostility among the aggrieved employees and also reduce employee morale.

- It is possible that employees might retaliate against the supervisors, which may further worsen the situation.

- Employees may tend to continue the undesired behaviour once the threat of punishment is withdrawn if he/she has not properly learnt the desired behaviour.68

Social Cognitive Theory

Social cognitive theory was discussed by Albert Bandura. According to this theory, an individual’s behaviour in a situation is a function of the meaning of that situation to him. People make meaning out of the situation through three interrelated components. They are: (i) personal goals and incentives, (ii) sense of self-characteristics and (iii) perceived behaviour options.69 This theory emphasizes that learning takes place in a social context and that much of what is learned is gained through observation of social environment. The basic assumption of this theory is that there are reciprocal interactions among personal, behavioural, social and environmental factors.

This theory states that people are motivated to develop a “sense of agency” (called human agency) in which individuals are proactively engaged in their own success and development. Sense of agency is something that enables individuals to recognize themselves as related to the world via complex causal chains/networks. This “sense of agency” enables individuals to apply a great extent of control over important events (thoughts, feelings and actions) of their life.70 This theory further states that people affect and get affected by individuals’ actions and environment in a reciprocal and bidirectional fashion. Thus, every individual’s behaviour is the product of constant interaction between cognitive, behavioural and contextual factors.

As per this theory, the process of motivation includes setting goals by individuals, self-evaluation of progress, deciding the outcome expectation, acting in accordance with values, social comparisons with other people (to obtain information about their learning and goal achievement) and lastly, self-efficacy (a measure of one’s own capability to complete tasks and attain goals).

Evaluation of social cognitive theory—Researches on the social cognitive theory support the fundamental assumptions of this theory, namely, cognitive factors have an effect on the personality development and this in turn affects the performance, productivity and motivation.71 However, this theory has been criticized for failing to connect all its concepts under one unified principle.

Attribution Theory

Attribution theory was popularized by Fritz Heider. This theory focuses on the causes that people attribute to the perceived successes or failures in their lives. This theory attempts to offer explanation for the beliefs individuals have about why they behave in the way they do. A person may attribute his/her failure in a particular task or mission to his/ her own lack of effort and ability or as another person’s fault. In the words of Kelly, “attribution theory concerns the processes by which an individual interprets events as being caused by a particular part of a relatively stable environment.”72 Earlier, people used to attribute the positive outcome or achievement–situation to four main causes. They are: ability, effort, task difficulty and luck. Subsequently, the causes have been expanded to include intrinsic motivation, interest, mood and superior’s competence as well.73

Attribution theory also deals with how superiors deal with the performances of others. For instance, a manager who attributes the outcome (success or failure at task) to an employee’s skills will adopt different approaches towards outcome. Their approach will be different from those who attribute the outcome to the situation. Some researchers insist that attribution theory is closely linked to achievement theory and control theory.74

Evaluation of attribution theory—Even though attribution theory is not strictly a motivation theory, it is viewed as a kind of motivation theory for the reason that it helps in understanding how people interpret their success or failure. This theory also emphasizes that organizations should first change the belief of the employees as to the cause of their success or failure before making changes in motivational tools and strategies. This theory also enables managers to understand why some people try hard to achieve success despite failure while others are not keen to persist with their efforts in the event of failure.75

However, this theory has a few weaknesses. For instance, it is difficult for the people themselves to understand the explanations of how they think of their success or failure. This theory fails to recognize the role of emotions in shaping individuals’ belief about their success or failure.

Control Theory of Motivation

Control theory (also called negative feedback loop theory) of motivation was discussed by Lord and Hanges. This theory initially focused on the machine-based system; it was then modified to suit the human system of motivation. According to this theory, the human action and motivation is based essentially on the negative feedback loop. The feedback loop comprises a series of inputs and outcomes that typically function on a circular path.76

The basic assumption of this theory is that an individual’s behaviour is controlled by a system under which his present condition (actual state of performance) is compared with the standard condition (desired state of performance). If there are any discrepancies (negative feedback) in the comparison between the current and desired conditions, necessary behavioural strategies within the system are adopted to reduce such discrepancies and bring performance back to standard.

This system is self-regulatory in the sense that the comparison and corrective actions are done as a part of the system itself. This theory aims at offering a viable model for the way the goals and feedback affect the behaviour and performance of people in their job.

Evaluation of the control theory—Control theory of motivation can facilitate the managers understand why people have goals, why they are motivated to achieve and why these goal should be dynamic. This is one of the few theories that talk more about an individual’s self-regulation than external stimuli like goals and incentives.

The weakness of this theory is that it assumes that individuals know exactly what they should do when they receive a negative feedback. But there may be situations when individuals know their deficit but are not clear about what needs to be done to deal with it. Besides content and process theories, McGregor’s theory X and Y and Ouchi’s theory Z have made important contributions to the study of employee motivation. We shall now discuss them.

McGregor’s Theory X and Theory Y

Douglas McGregor, in his book The Human Side of Enterprises, published in 1960, explains two different kinds of theories or assumptions about human behaviour. They are theory X and theory Y. Theory X holds a negative (traditional) view of the workers while theory Y holds a much refined and positive view of workers.

The scientific management school of thought inspired McGregor to develop theory X. This theory suggests that productivity could be increased through division of jobs into smaller units of work (tasks) and by assigning each worker a small range of well-defined tasks. The elements of these theories are:

Theory X—The general assumptions of this theory of workers are:

- Workers have an inherent or natural dislike towards their job and they will avoid their job if it is possible for them.

- Workers have little or no ambition in their work life and are not concerned about their career growth.

- They tend to resist changes and also avoid responsibilities.

- They are basically self-centred and do not care about organizational goals and objectives. In other words, their goals are contrary to the organizational goals.

- They prefer to be led by others rather than lead others.

- Workers in general are not intelligent and are mostly gullible or innocent.

- Workers are generally poor decision makers.

- They need to be monitored and controlled closely to make them work effectively.

The fundamental assumption of this theory is that people work only for money and personal safety and security. Theory X requires organizations to do the following to manage and motivate the workers and to increase productivity:

- Minimizing the number of situations in which workers are required to make decisions by themselves.

- Providing mainly extrinsic financial rewards to workers.

- Monitoring the activities of the workers through tight or very close supervisions.

- Imposing tight discipline and enforcing strict performance correction measures to encourage performance.

- Conducting extensive training programmes to workers on how they should do their work.

In contrast to theory X, the assumptions of theory Y are positive about workers. McGregor developed theory Y after becoming aware of the flaws in theory X. We shall now discuss the assumptions of theory Y.

Theory Y—The important assumptions of this theory about workers are:

- Workers enjoy their work if it can be as natural as playing or resting. Work may be a source of satisfaction for workers. They can perform jobs well without any threat of punishment.

- Workers are self-directed and self-controlled in fulfilling the objectives to which they are committed. Workers not only accept responsibilities but also seek it under proper condition.