CHAPTER 6

Group Judgment and Decisions

Group judgments can be different from individual judgments. Although the basic heuristics and biases that apply to individuals also apply at the group level, a number of biases are specific to groups. Group discussions such as brainstorming may lead to better decisions than those made by individuals. Game theory is a mathematical theory of human behavior in competitive situations, such as project management, in which players interact.

Psychology of Group Decision-Making

Project managers do not operate in a vacuum, and important decisions in project management are rarely made individually. They usually involve a number of people and are the result of discussions between various stakeholders. For example, project managers collaborate with project team members and communicate with clients to develop a balanced project plan.

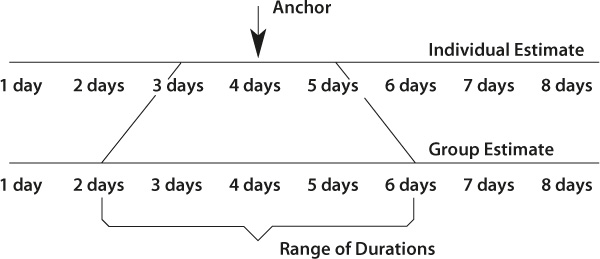

If decisions are made in groups, are they subject to the same mental errors as those made by individuals? For example, do heuristics such as availability and representativeness, which we discussed in relation to individuals in chapter 2, work at a group level? Simply put, the answer is yes: individual heuristics and biases do continue to operate at a group level. Moreover, these biases can be even stronger in groups than in individuals (Plous 1993). For example, when estimating the duration of an activity, if you are working alone you may use a certain number as a reference point or anchor (say, four days) and then come up with the range of durations using a reference point of between three and five days (figure 6-1). This bias results from the anchoring heuristic (which we discussed in chapter 2). A group may use the same reference point (four days) but come up with a wider range (between two and six days).

A number of biases are specific to groups. One of them is called group polarization (Moscovici and Zavalloni 1969), in which people are more likely to advocate risky decisions after participating in group discussions. This effect has major implications in project management. Group polarization leads to greater risk-taking on the part of the group than would occur with individuals. For example, project managers may be more inclined to agree to a risky extension of a project scope after a discussion with peers.

Figure 6-1. Developing a Range of Activity Durations

Group polarization affects more than risk-taking. Group discussions can amplify the preferences or inclinations of group members. If a project team member already had an opinion regarding a certain issue, after a discussion in a group he or she may have a much stronger opinion about the issue. In one experiment, simulated juries were presented with weak incriminating evidence. They became even more lenient after group discussion. At the same time, juries presented with strong evidence became even harsher (Myers and Kaplan 1976).

With this knowledge, it is fair to ask whether group discussions actually improve the quality of decisions. In other words, are several heads better than one? The psychologists’ answer is a qualified “yes.” The qualification is that it depends on the type and difficulty of the problem. Some problems are better handled in groups, while others are not. Reid Hastie (1986) reviewed three types of problems:

1. Judgment of quantities is related to the estimation of project cost, duration, and other parameters. Groups are usually more accurate than individuals in these types of decisions. Psychologists estimate that group judgments can be 23–32% more accurate than individual judgment (Sniezek and Henry 1989, 1990).

2. Logical problems are related (in project management) to finding solutions to complex business or technical issues. Groups perform better than the average individual; however, highly skilled or experienced team members who act alone usually outperform the team.

3. Judgments in response to general knowledge questions are related to finding factual data relevant to a project. Groups perform better than the average individual. Yet the best member of the team usually equals or surpasses the performance of the team.

Aggregating Judgment

Members of project teams often express differing opinions. Is it possible to mathematically calculate the judgment of a group, based on the judgments of its individual members? That is, can we average, say, the cost and duration estimates offered by different members of a group? And would doing so even be useful? Psychologists and decision scientists have extensively researched this problem (Goodwin 2014) and concluded that it is possible to do so if members of the group have similar expertise and work in the same environment. However, simple averaging of individual judgments can cause major errors. It is like the “average” body temperature in a hospital, which is always normal. Why? Because, while somebody may have a fever, there is also probably someone who is dead and therefore cold.

Is there a best way to come up with group judgments? The solution is to organize the discussion within a team in which the group as a whole makes a decision. For example, while the Supreme Court justices may have different opinions on a particular case, they deliver a common ruling in which they basically aggregate their judgments. The problem is that it is not always possible to come to a consensus as a result of a group discussion.

Group Interaction Techniques

Research in group judgment and decision-making confirms what we already know intuitively: group discussions can lead to better decisions. Now let’s see what techniques can be used to facilitate these types of discussions. Based on how team members communicate with each other, these discussions can be separated into four categories:

1. Consensus. These are face-to-face discussions between group members where one judgment is eventually accepted by all members. This is one of the most common techniques in project teams. Team members meet regularly to discuss certain issues in anticipation that they will come to a consensus. The problem with this method is that some team members, who often happen to be managers, can monopolize the discussion and significantly influence the final judgment. This effect can be called the “We discussed and I decided” outcome.

2. Delphi. The Delphi process helps to protect against the “We discussed and I decided” effect. Group members don’t meet face-to-face. Instead, they provide their opinions anonymously in a series of rounds until a consensus is reached. Delphi techniques require a facilitator, who sends out questionnaires to a panel of experts. Responses are collected and analyzed, and common and conflicting viewpoints are identified. The Delphi method was developed at the RAND Corporation, a nonprofit global policy think tank, at the beginning of the Cold War to forecast the impact of technology on warfare. The name of the technique derives from the Oracle of Delphi.

3. Dialectic. In this technique, members are asked to discuss those factors that may be causing biases in their judgments. Group members who hold differing opinions on a specific topic try to understand each other and resolve their differences by examining contradictions in each person’s position.

4. Dictatorship. This process uses face-to-face discussions that lead to the selection of one group member whose judgment will represent that of the group. Interestingly, according to Sniezek and Henry’s research (1989), judgments produced by the dictatorship technique were more accurate than those produced by any of the other techniques. The dictatorship technique may be useful when a project team is trying to solve business or technical issues that require specific knowledge or expertise. In this case, it is important to identify the person with the best knowledge of the subject and discuss the issue under his or her guidance.

5. Decision conferencing. This technique has been proven to be effective for analysis of complex problems. Decision conferencing involves having experts get together for one to three days in face-to-face meetings that are moderated by a decision analyst. The analyst acts as a neutral observer and applies decision analysis methods and techniques during the meetings. The analyst creates a computer-based model that incorporates the judgment of the experts. It is extremely important that he or she does this in parallel to the discussions so that the experts can examine the results as the discussions progress. Through examination of the models, experts are able to create a shared understanding of the problem and then to come up with a decision. Essentially, the analyst is applying the decision analysis process described in this book: framing decisions, creating a model, and performing analysis in parallel with the decision conference.

Brainstorming

A good technique for creating a list that includes a wide variety of related ideas is brainstorming. In theory, brainstorming can be performed individually, but it is more effective if it is performed by a group. Brainstorming can be a very effective method in project management, to decide questions such as these: What is the best course of action in a complex business situation? What features of the new product can be developed first? What are the potential risks and opportunities for this project?

A number of techniques and tools are used for brainstorming (Clemen and Reilly 2013). The main goal of these techniques is to promote creative thinking among group members. All these techniques have the following rules:

1. Do not present detailed analysis of the ideas.

2. All ideas are welcome, even the absolutely “far-out” ideas; groups should come up with as many ideas as possible.

3. Group members are encouraged to come up with ideas that extend the ideas of other members.

Psychologists have discovered that brainstorming can be more effective if several people work on a problem independently and then share and discuss their ideas (Hill 1982). Many effective brainstorming techniques are built around this idea.

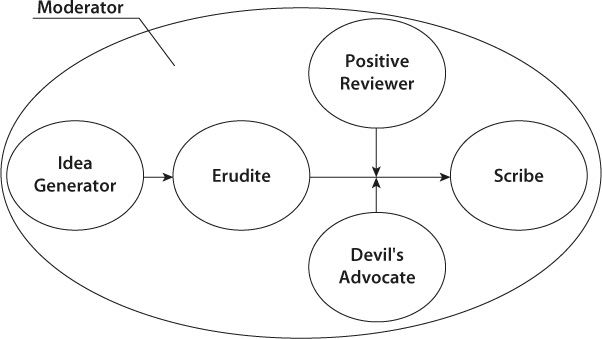

Figure 6-2 describes a brainstorming technique that we recommend as part of good project decision analysis. In it, each group member takes on a specific role. These roles are defined well before the meeting, so each participant can mentally prepare for the process. There are at least six roles, although some can be combined:

1. Idea Generator: develops as many ideas as possible but does not evaluate them

2. Erudite: provides more information about these ideas based on his or her own factual knowledge

3. Devil’s advocate: criticizes the ideas presented

4. Positive reviewer: finds positive elements in the ideas

5. Facilitator or Moderator: organizes the discussion and makes sure that all participants follow their roles

6. Scribe: writes down the ideas and distributes them to group members in an easy-to-digest format

Two important rules should be followed when using this process:

1. Everybody has the right to occasionally move outside the boundaries of his or her role; however, it is important to stay within one’s role for the discussion of a particular topic or for the duration of a brainstorming session.

Figure 6-2. Brainstorming Technique

2. Two to four meetings, each with very a short time frame (15–30 minutes), are conducted with breaks of a day or two in between. The limited time frame is strictly enforced. Long breaks between meetings give participants the opportunity to think more about the ideas. Roles can be changed for the next meeting.

Another brainstorming method is called the nominal group method (Delbecq et al. 1975). At the beginning, each group member writes down as many ideas as possible. During the meeting the members present these ideas, the group evaluates the ideas, and the moderator records them. After the discussion every group member ranks the ideas. These rankings are then combined mathematically to select the best ideas.

Effective brainstorming is an art. It takes practice to achieve good results.

If you and your team have not brainstormed before, you should not expect miraculous results from the first meeting. Don’t be discouraged, for brainstorming requires a certain amount of practice. Therefore, if you believe that brainstorming would be useful for your projects, we recommend beginning by practicing on less important project issues before getting into complex problems. And the role of the moderator is important, for an inexperienced moderator can block good ideas. Good moderators set a positive tone for discussions and encourage creative ideas.

Tools for Facilitating Discussions

A number of tools can help with strategy planning, brainstorming, process improvement, and meeting management. During discussions you can record ideas and conclusions, create several diagrams and flowcharts, and share them among others regardless of the particular geographical locations of group members. In addition to analytical tools such as cause-and-effect diagrams and decision trees, tools are available that help to organize meetings by creating agendas and minutes, facilitating online discussions, defining team action items, and so on.

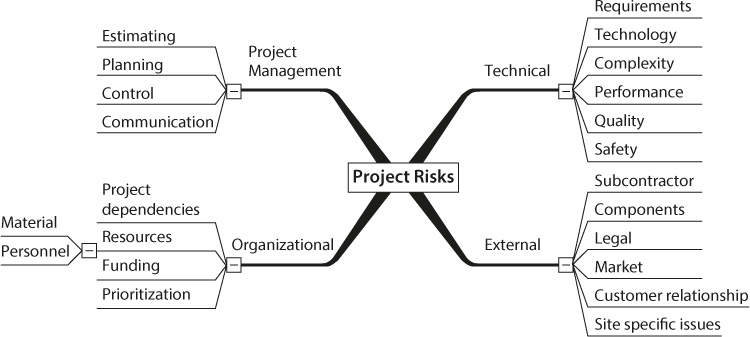

In recent years mind-mapping software tools have become popular in project management. Vendors of this software have sold hundreds of thousands of licenses, and we don’t believe that this is a temporary trend; apparently project managers have realized the benefits of mind-mapping tools. A mind map is a diagram used to represent ideas, activities, risks, or other items linked to a central theme. In a mind map, the central theme is often illustrated with a graphic image. The ideas related to the main theme radiate from that central image as “branches.” Topics and ideas of lesser importance are represented as “sub-branches” of their relevant branch. The mind map shown in figure 6-3 is based on a risk breakdown structure adapted from the PMBOK Guide (see appendix C).

A mind map helps you record ideas in a structured way and to review them later. You can find a list of vendors of these tools and other tools in appendix A.

When we think about project management tools, we mostly recall software tools, various paper templates, and checklists. But you don’t need expensive or fancy software to facilitate discussions. A number of simple hardware tools are useful. In addition to traditional flipcharts or chalkboards, many project teams use electronic whiteboards, which automatically record information written on the whiteboard to a computer.

A Few Words about Game Theory

“Life is but a game,” said Hermann, a character in Peter Tchaikovsky’s opera The Queen of Spades. Today we can view decision analysis through the lens of modern game theory, a mathematical theory of human behavior in competitive situations that studies decisions made in an environment in which players interact. In other words, game theory studies how an individual selects optimal behavior when the costs and benefits of each option depend upon the choices of other individuals. While Hermann wasn’t thinking about modern game theory, and was not even aware of it, he was right that “life is but a game.” Game theory helps to analyze many processes in the common conflicts we deal with in our lives, such as stock market behaviors; political processes, including wars and elections; business activities, such as negotiations, auctions, mergers, and investments; and, yes, project management.

Figure 6-3. Mind Map of Project Risks

Game theory studies how an individual behaves depending on the choices of others.

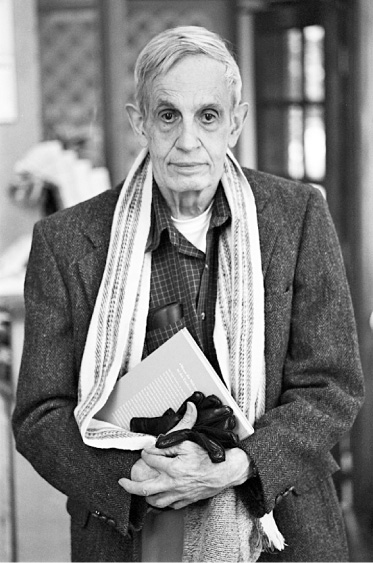

Game theory began with the classic book Theory of Games and Economic Behavior, by John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern (1947). The RAND Corporation used game theory to help define nuclear strategies. Do you remember the movie A Beautiful Mind? It is the biography of John Forbes Nash Jr., a mathematical genius who fell victim to schizophrenia after making amazing strides in game theory and economics. In 1994, Nash (figure 6-4) shared the Nobel Prize in economics with John C. Harsanyi and Reinhard Selten for their work in game theory. Eleven years later, Robert J. Aumann and Thomas C. Schelling received the Nobel Prize, also in economics, “for having enhanced our understanding of conflicts and cooperation through game-theory analysis.” And in 2012, the Nobel Prize in economics was awarded to Lloyd Shaple, of UCLA, and Alvin Roth, of Stanford University, also for their contribution to game theory.

Figure 6-4. John Forbes Nash in 2006 (Photo by Peter Badge)

Why do some projects succeed in promoting cooperation while others suffer from conflict between different stakeholders? Here is a very simple example of a situation in which you could apply game theory:

You are the manager of an IT project. Your client wants to make a change that he considers critical. You realize that this change will have major implications for your system and could significantly delay the project. Is this a source of potential conflict, or is there a way to compromise? Your decisions as a project manager are influenced by the choices and actions made by other stakeholders. Or, contrarily, the decisions of all project stakeholders are influenced by your decisions. The course of the project depends on the outcome of this “game.”

Game theory offers mathematical mechanisms that can be helpful in solving these issues. Here are a few examples of simple games. Schelling (1971) described the “mattress problem,” where there is a two-lane highway and one lane is jammed as people slow down to gawk at a mattress that has fallen from a car. The question is, who should stop to pick up the mattress? The people at the back of the traffic jam are only aware that there is a problem but do not know the cause. The people at the front can see the mattress but want to get out of the traffic jam as soon as possible. By the time they are at the mattress, they are at the end front of the traffic jam, and it will take them less time to ignore the mattress than to remove it. If they remove it, they will save everyone behind them a great deal of time—but at a cost to themselves.

The mattress dilemma can manifest itself in project management. If you have a software project for which your team cannot easily find the time to develop a testing tool, should you develop one anyway? You have completed your project, so you don’t need the tool, and it will only be used to test someone else’s software. When the application is done, why bother creating the testing tool, which can be used for future applications developed by somebody else? In psychology this effect is considered a mental trap, and this specific one is called the collective trap.

Another example of a game is deciding when to buy a ticket for a train. A limited number of trains will be leaving the station. If you arrive too late for the train for your destination, you may not get a ticket. If you arrive too early, you will have to stand in line for a long time. So, you will want to arrive at the station at a time when it maximizes your chances of getting a ticket while minimizing your wait standing in line. Your choice will depend upon when the other people decide to arrive. Game theory helps to find a mathematical answer to these types of problems.

One of the important concepts of game theory is called the “Nash equilibrium,” named after John Nash. The Nash equilibrium is a solution to a game in which no player gains by unilaterally changing his or her own strategy. In other words, if each player has chosen a strategy and no player can benefit by changing his or her strategy while the other players keep theirs unchanged, then the current set of strategies with their corresponding payoffs constitutes a Nash equilibrium. A Nash equilibrium can be reached in the train ticket game, where everybody arrives at the station in such a way that all waiting times are minimized.

As a project manager, you will most likely not use game theory directly. Applications of game theory to project management are still under research, but we believe that practical solutions and tools will soon be available for project managers. If you want to read more about game theory, you will find some references in this book’s Future Reading section.