CHAPTER 19

Making a Choice with Multiple Objectives

Multi-criteria decision-making is a process that helps you incorporate conflicting objectives into your decision-making. The mental strategies we use to make choices with multiple objectives are the recognition, lexicographic, and elimination-by-aspect heuristics, among others. There are two approaches to multi-criteria decision-making: (1) convert all nonmonetary criteria to monetary equivalents, and (2) use special models and methodologies, such as a scoring model, to combine criteria of a different nature.

What Is Multi-Criteria Decision-Making?

In 2018, Dutch security services expelled Russian spies over a plot targeting the chemical weapons watchdog named the “Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) in the Hague” (Harding 2018). Unlike James Bond, real-life spies need to submit an expense report. One of the expelled spies had retained his taxi receipt: he went by taxi from the Russian spy agency GRU’s headquarters in Moscow to the city’s international airport. He paid around $12. It is unknown if he was repaid, or if he left a tip. The taxi company later confirmed that receipt was real. The GRU has multiple objectives; among others, they need to ensure successful spying worldwide while managing expenses. Without controls in place, the entire Russian budget could possibly be spent funding the GRU’s various capers. So, how can the GRU balance these objectives? In practical terms, how should the agency plan its spying projects to ensure high quality results, the physical safety of spying personnel, the lowest costs, and accountability?

Here is another example: global warming is one of the most complex, controversial, and highly political topics in the world today—which makes it a good subject to use as we examine the process of weighting different criteria in decision-making. As a society we see the benefits of economic growth, yet we also want to protect the environment. Measuring the effect that economic development has on climate change requires dealing with many uncertainties, since predicting economic processes and forecasting climate change are both inexact sciences. The main question is how to balance these conflicting criteria and make correct decisions. Similar types of problems, though not as complex, arise all the time in our projects as well as in our personal lives:

• A software company’s dilemma: delivering software on time without jeopardizing quality

• A car manufacturer’s dilemma: ensuring the durability of car parts without increasing the car’s selling price

• A personal dilemma: determining the location of your home in either an expensive inner-city location close to work or an inexpensive location in the suburbs

In chapter 9 we discussed how to:

1. Determine project objectives and decision-making criteria.

2. Rank these objectives.

3. Identify potential trade-offs.

Eventually, we have to make a decision based on the criteria we have determined. In doing so, we need to understand how people make decisions with multiple objectives.

Here is a simple example: let’s assume that you need to buy a new printer for your home office and you have three alternatives. Let’s also assume that you need to use a single indicator for the analysis of these three alternatives—for example, cost, which is an indicator that captures all the positives and negatives of these alternatives. In this case, the decision is clear: select the printer with the lowest cost. Yet you will rarely come across criteria that allow for such an easy decision.

The problem is that in making decisions that contain multiple objectives, it is very difficult to put the different objectives into one equation. How do you translate quality-of-life issues (such as whether your chosen printer fits into your small home office, and how noisy it is) into monetary terms? In the same way, how does a corporation balance higher profits with a commitment to the environment? As a result, we tend to solve these problems intuitively, very often based on our emotions at a given moment.

Oil companies are not the cause of our ecological problems; rather, depending largely on the fossil fuels they produce has for a century been the way our economy operates. Businesses and commercial projects are basically concerned about a single criterion when they make decisions. This criterion has many different names: maximizing profit, improving NPV (net present value), maintaining cash flow. Essentially, they are all about money. Oil companies must weigh all their exploratory, production, and marketing decisions against this criterion.

In reality, in our economy if a company spends money on the environment, it is not a form of corporate altruism; it is doing so for the following reasons:

1. The company is going to make money out of it directly or indirectly. (For example, if a company invests in the environment to improve its public image, this should indirectly improve its profitability.)

2. The company is mandated to perform certain activities by government regulations.

Most projects are similar in that decisions are concerned with criteria that are directly associated with financial outcomes: scope, duration, and cost.

Other parameters, such as quality and customer satisfaction, can also be associated with money, although the associations are less direct. But what about other criteria, such as safety, the environment, and community and employee relationships? If these criteria are not accounted for, major problems can arise. To address all these issues, we need to use multi-criteria decision-making methods.

Multi-criteria decision-making helps incorporate multiple conflicting objectives formally into the decision-making process.

The Psychology of Balancing Multiple Objectives

As we have already learned, people make judgments about complex issues, using simplification strategies or heuristics. One of these rules of thumb is called the recognition heuristic (Goldstein and Gigerenzer 1999). Basically, if we have two alternatives, we usually make a choice based on the alternative we recognize. For example, if you are making choices between two components for your classic car, instead of analyzing all the pros and cons of the components, you will probably select the component that comes from a manufacturer you know. This explains why we often select a product based on brand name instead of performing a detailed analysis of features and benefits.

But what if both suppliers are equally recognizable? You may just make a random selection or go with your previous choice. Often your choice is affected by recent events, news, good presentations, or speeches—the availability heuristic we discussed in chapter 2. For example, you attended a presentation about the importance of quality management processes. The speaker presented examples of some successful projects where quality management processes were followed. But what impressed you most was a case study that showed the obverse: how the neglect of quality management led to disastrous consequences.

After that presentation, you will probably think that quality is the only criterion you need to consider. As a result, you may concentrate on quality improvement, to the detriment of cost, safety, and the environment. If you ignored the other competing objectives, you would deliver a high-quality but over-budget project and would possibly face lawsuits from workers’ safety organizations and environmental groups.

Another mental strategy is called the lexicographic heuristic (Tversky 1969). In it, you rank criteria from the most to the least important. For example, the price of a component will be the most important, performance will be less important, and the country of manufacturing will be the least important. If all components have the same price, you make a selection based on performance. If all components have the same performance, you make a choice based on your preferred country of manufacturing.

This heuristic is called lexicographic because a similar algorithm is used to order words in dictionaries. For example, “dusk” will follow “desk” because when first letters are the same (d), second letters are used to order the word. This is called a ranking heuristic.

If one criterion is significantly more important than another, the lexicographic heuristic works well. However, if the relationship between various criteria is complex, this heuristic can cause problems. If you are basing your decision on a weighting of price, performance, and the manufacturer’s delivery history, the ranking becomes much more complex, and the ability to make the correct choice becomes more difficult.

Another heuristic is called elimination by aspect (Tversky 1972). We already discussed the analytical formal method of creative thinking by using filters (see chapter 5), which is conceptually similar to this heuristic. Elimination by aspect is a mental strategy in which you eliminate a potential choice if it does not satisfy certain conditions. For example, you can eliminate all alternatives that have high prices, show low performance, and are manufactured outside your country. As a result, only a few potential alternatives (if any) will remain. The problem with this heuristic is that some potentially good alternatives can be eliminated because this approach does not include an analysis of trade-offs. For example, the price of a component may not be preferable; however, all other attributes may be very good. Alternatively, the price of a component may be very good, but the quality is poor. If you use the elimination-by-aspect heuristic, depending upon your ranking schema, you could unintentionally reject good alternatives and select alternatives that are less than optimal.

If you feel that intuitive strategies are not enough to help you make a choice with multiple objectives, you can use a variety of analytical methods to solve these puzzles.

Two Approaches to Multi-Criteria Decision-Making

Two approaches can help you make a decision when dealing with multiple objectives (Schuyler 2016):

1. Convert all nonmonetary criteria to their monetary equivalents.

With this approach, you convert all your criteria into dollar equivalents. The problem is that this type of accounting does not always work. For example, as of 2011, the Environmental Protection Agency set the value of a human life at $9.1 million. The Food and Drug Administration put it at $7.9 million, while the Department of Transportation figure was approximately $6 million (Partnoy 2012). These numbers are used in decision-making performed by these agencies, in particular deciding how much money they should be willing to spend to save a person from dying.

How much do you think your own life is worth? Are you worth more or less than your manager? Clearly, it is difficult to come up with some cost estimates, especially for criteria like the value we put on a human life that everyone will agree with.

2. Use special models and methodologies to combine criteria of a different nature.

Health, safety, environment, job satisfaction, corporate cultures—these are criteria that are used to make project decisions but are extremely difficult to convert to monetary equivalents. After you identify and rank these criteria, you must come up with a formula or algorithm to rank alternatives based on them. We will review one of the simplest methods: the scoring model.

Ranking Criteria with the Scoring Model

The scoring model is a relatively easy method for identifying the best alternative in a multi-criteria decision problem. Here is how it works:

1. Identify your decision-making criteria. This occurs during the identification of the project objectives (see chapter 9).

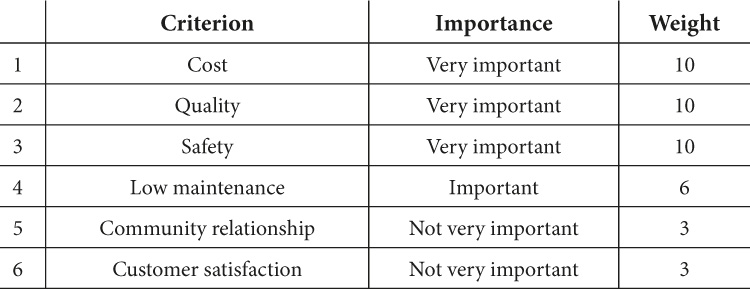

2. Assign a weight for each criterion, which is its relative importance in relation to the other criteria. An example is shown in table 19.1.

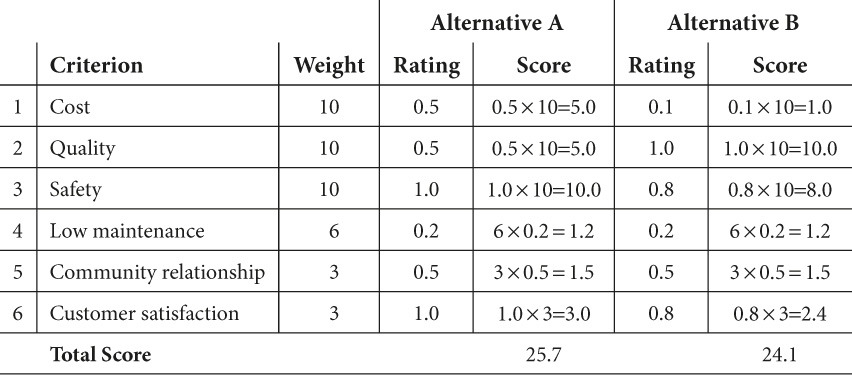

3. Assign a rating to each criterion that shows how well each decision alterative satisfies the criterion.

4. Compute the score for each alternative. The example is shown in table 19.2.

Table 19-1. Decision-Making Criteria and Their Relative Weights

Table 19-2. Score Calculation for Two Alternatives

In this example, alternative A has highest score and should be selected.

A major flaw with this method should be obvious right away: weights for different criteria, as well as ratings, are highly subjective. In table 19.2, why, for example, does “cost” have a rank of 10 and “customer satisfaction” a rank of 3? These weights actually reflect an organization’s decision policy, which is usually well established long before a ranking is done, and the selection of criteria and assigning of weights for all portfolios or projects is based upon that policy. The selection of criteria and assignment of weights can be the responsibility of a panel of experts that coordinates the decision analysis process while taking into account the organization’s decision policies.

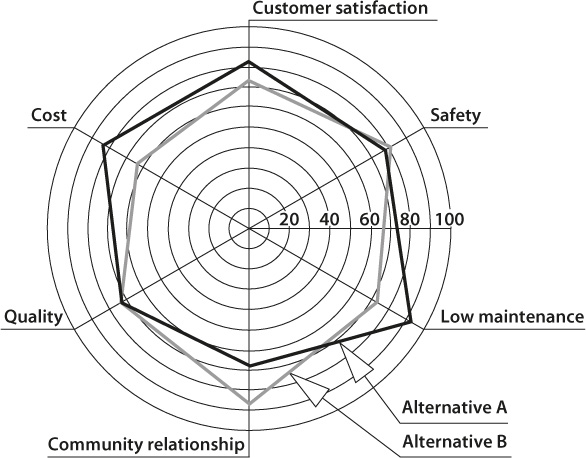

David Skinner (2009) recommends using a radar chart to visualize different strategies against multiple objectives. When you select multiple objectives and rank different strategies based on these objectives, you can display them on a chart similar to figure 19-1. The only limitation is that in this example the criteria have been assigned the same weight.

Advanced Methods of Multi-Criteria Decision-Making

If you can take only one key point away from this chapter, it is that the roots of many problems, such as global warming, lie in our inability to balance different objectives in our decision-making processes. A critical mistake that many project managers make is to base their decisions on a single criterion—usually money—and then select the alternative that is the cheapest or has the most revenue potential.

Figure 19-1. Radar Chart Used to Compare Strategies against Multiple Objectives

In most cases, the simple scoring method and the radar chart will provide good solutions for problems involving multiple criteria. However, if you are dealing with large and complex projects, we strongly recommend that you engage the services of an independent consultant. Consultants have experience with many tools and methodologies to deal with multi-criteria decision-making. We include a list of these methods with references in appendix D.