CHAPTER 9

Defining Project Objectives

A project can have several objectives and therefore a number of decision-making criteria. To select a viable alternative, decision-makers need to make a number of trade-offs. Aligning objectives is important to be able to achieve project goals. Project objectives and trade-offs can both be determined by defining a hierarchy of fundamental objectives or a network of means objectives.

Different Objectives and Different Criteria for Decision-Making

Sgt. Bilko was a hilarious 1996 movie (starring Steve Martin) and a long-running TV series (starring Phil Silvers). While on active duty in the U.S. Army, Bilko was involved in a number of operational and project-related activities (actually, they were more like escapades), including gambling, organizing of sport competitions, renting out military vehicles, and even planning for a day care center in the military barracks. Clearly, Bilko had different objectives than his employer, the U.S. Army. In the movie, one of the main objectives of the military unit at the fictional Fort Baxter was designing and developing a hover tank, not advancing Bilko’s fortunes.

Identification of project objectives can seem to be a trivial process. In many cases, project managers just skip this step because from their point of view everything is quite clear: the project must be completed on time, within budget, and according to requirements. However, project objectives can often conflict with each other, and decisions should be made by carefully balancing all of them.

According to the PMBOK Guide, one of the important steps in project management is “establishing clear and achievable objectives.” The Guide defines project objectives as something toward which work is to be directed, a strategic position to be attained or purpose to be achieved. According to the Guide, identifying project objectives belongs to the area of “project integration management,” and particularly to the stage for developing [a] preliminary project scope statement.

When making a decision, a project manager needs to use various indicators to determine which alternatives will best achieve the project’s objectives. These indicators are called decision criteria. If we take our example of Sgt. Bilko, we can see that because Bilko and the U.S. Army had different objectives, they also had different criteria for decision-making (table 9.1).

In fact, different project objectives are classic fare for any comedy. If you want to make a successful comedy, here is a simple step-by-step recipe:

1. Come up with a project; the most common comedy projects are engagements, divorces, bank robberies, and alien encounters.

2. Define different project goals for each project stakeholder.

3. Hire Steve Martin as a star.

4. Relax and have your accountant count your millions.

Regrettably, poor project management is never a comedy for those who suffer its consequences; therefore, realigning project objectives has to be a priority for project managers. In a project with multiple objectives, project managers should consider a number of decision criteria. This process is called multi-criteria decision-making. Examples of decision criteria can be:

• Economic indicators, such as net present value (NPV), rate of return (ROR), and project cost

• Project duration indicators, such as total duration, finish time, and duration of particular phase

• Resource usage, including material and work resources

• Project scope indicators, such as number of features implemented

• Quality indicators, such as number of defects

• Safety indicators, such as number of accidents

• Environmental indicators, such as level of emissions

Table 9-1. Different Goals and Decision-Making Criteria for U.S. Army and Sgt. Bilko

|

Sgt. Bilko |

U.S. Army |

Objectives |

1. Financial performance of Bilko’s army unit 2. Entertainment and gambling |

1. Improve military preparedness 2. Design and production of a prototype hover tank |

Decision-making Criteria |

1. Revenue 2. Quality of entertainment and gambling 3. No transfers to a location in Greenland |

1. Quality of military training 2. Completion of hover tank project on time and within budget |

Unfortunately, not all criteria can be quantified. For example, it is difficult to measure improvements in the work environment or in business communication. Still, these indicators should be considered decision-making criteria, as well.

Aligning Project Objectives

Why do we have different objectives and different criteria for making our choices? There are two principal reasons:

1. The project must satisfy different conditions and constraints, such as being completed within budget, brought in on time, and implemented according to the specifications.

2. Project stakeholders may have different expectations, and therefore they may use different objectives and decision-making criteria.

An example of conflicting objectives is found in the difference between long-term and short-term goals. Should a company complete a software development project as fast as possible? Contrariwise, should it extend the schedule to implement software architecture improvements that will ensure that future changes to the software will be easier to implement?

The PMBOK Guide includes a few examples of conflicting objectives. For instance, the vice president of research and development of an electronics manufacturing company wants to use state-of-the-art technology; the vice president of manufacturing wants to concentrate on world-class practices; and the vice president of marketing is focusing on a number of other features. This is not necessarily a bad thing. When different stakeholders hold different objectives, the project can benefit as long as the project manager is capable of balancing them properly.

In many cases, conflicting project objectives should not exist in the first place. Nevertheless, individuals, groups, project teams, and departments manage to come up with conflicting expectations. A classical example of conflicting goals is share price. Senior management’s goal to improve and maintain a company’s share price does not necessarily require improving the performance of the company’s projects.

Personal objectives may differ from organizational ones because each member of a project team may have personal considerations and specific incentives. If a person is trying to make a career in the organization, he or she may be risk-averse and might avoid any project that entails a large amount of risk, such as product improvements. In this case, the less the person is involved in changing the product, the less likely it is that he or she will be blamed if anything goes wrong. Not being associated with a bad project will help you in the promotion process, but it means that the organization will be less likely to take on risky projects and thus to gain the potentially larger benefit that they can produce.

Does this scenario sound familiar? Because of different objectives, personal criteria of success (promotion) may be different from the project’s success criteria.

There are many other situations of unaligned objectives. Often, project sponsors and project teams have different goals. Moreover, project objectives, and therefore the decision-making criteria, may change during the course of a project.

Decision Analysis as an Art of Trade-Offs

In many cases we will not be able to satisfy all our objectives at the same time. So, we must be prepared to make trade-offs. With a full understanding of the project objectives and decision-making criteria, project managers will be able to make an informed decision about when to sacrifice (in most cases, only partially) one objective to achieve another.

The decision analysis process will not resolve a difference in project objectives among project stakeholders. However, the process may expose potentially different expectations and goals.

How can decision analysis help identify objectives and potential trade-offs?

In reality, with most projects you will not need to perform a convoluted quantitative analysis. Instead, we provide you with the following three simple recommendations. Consider this a small mental exercise you may need to go through during the project initialization phase, or anytime you are required to make a critical project decision.

1. Identify project objectives. Include the objectives of the project stake-holders, and consider where and how they differ; based on these objectives, identify your decision-making criteria.

2. Rank these objectives. Determine which objectives are the most important.

3. Identify potential trade-offs. True, trade-offs are very subjective, but decision analysis methodologies offer a framework in which to make these trade-offs logically and consistently.

Decision analysis offers a number of tools that you can use to perform these steps. One of the common methods used to determine project objectives is a project objectives hierarchy.

Project Objectives Hierarchy

As you have already seen, a project can have a number of objectives, and there may be a complex relationship among them. The easiest way to discover these relationships is to create a diagram that includes objectives with their ranking, as well as trade-offs.

In general, there are two types of objectives:

1. Fundamental objectives are the goals that need to be accomplished during the course of the project. For example, maximizing the profit of Sgt. Bilko’s unit and providing entertainment are the fundamental objectives that Bilko wants to accomplish.

2. Means objectives help to achieve fundamental objectives. For example, “organizing golf tournament,” “selling Bilko beer,” or “renting out military vehicles” will help Bilko achieve his fundamental objectives.

How do you distinguish between means and fundamental objectives? The simplest way is to apply the WITI test (Clemen and Reilly 2013) by asking, “Why Is That Important?” This question is sometimes called the “Why does Sgt. Bilko need to sell magazine subscriptions to his soldiers?” test. The answer is: to maximize profit, which is Bilko’s fundamental objective.

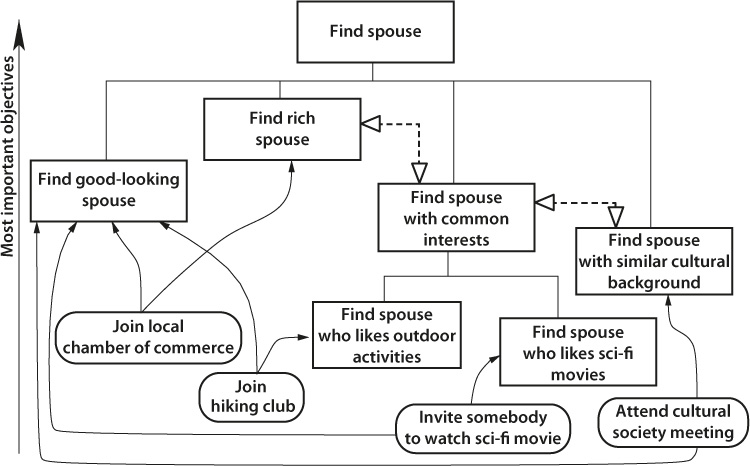

Relationships between objectives can be presented in the form of a hierarchy (for fundamental objectives) or a network (for means objectives) (Keeney 1996). Figure 9-1 is a type of diagram that we recommend for analysis of objectives. Let’s assume that you are involved in a project to find a spouse. Anybody who has been involved in such a project will realize that if this project is not well managed, the results can be frustrating. Finding the “right spouse” is the fundamental objective. Now, you can ask yourself, “What do I mean by that?” Your answer will probably be that you want to find a person who shares your interests; is reasonably attractive; belongs to a similar cultural, religious, or social group; doesn’t have too many bad habits; and is independently wealthy.

Figure 9-1. Project Objectives Hierarchy

Each of these objectives may have other, more specific, objectives. For example, if you are trying to find somebody who shares your interests, your partner may or may not have to like football. Fundamental objectives are shown in the diagram as rectangles.

After you have created this hierarchy, ask yourself this question: “How can I achieve these objectives?” It will help you come up with means objectives. For example, if you want to determine whether a person shares your cultural preferences, you can attend certain events, such as concerts, opera performances, duck hunts, or meetings of wiccans. Means objectives are shown on the diagram as ellipses.

The next step is to rank these objectives. Place the most important fundamental objectives at the top of the diagram. Finally, you may need to determine potential trade-offs. If you are trying to achieve several goals at the same time, you will likely not be able to complete the project at all. In our example of seeking a spouse, you may not want to put much weight on personal wealth if you meet a person with similar interests. (But if you do, don’t go making trouble in your FES-infected company.) These types of trade-offs can be depicted using dashed lines on the diagram.

Maximizing the Probability of Meeting Project Objectives

There is always a chance that project objectives may not be achieved. For example, the requirements may be uncertain and change over time. The goal of a project manager is to maximize the probability of meeting project objectives (Keisler and Bordley 2015). This is equivalent to maximizing project customers’ expected utility, as described in chapter 4. Solutions can be found using the multiattribute utility function when multiple project objectives need to be satisfied at the same time (Bordley and Kirkwood 2014).