CHAPTER 21

Did You Make the Right Choice?

Reviewing Project Decisions

Post-project reviews of project decisions are important because they allow you to improve future decisions. However, these reviews can be influenced by a number of psychological biases. For example, management will often believe that project failures were more readily foreseeable than they actually were. A corporate knowledge base should provide a source of information about previous decisions and their outcomes.

Why Do We Need Post-Project Reviews?

Now that you have completed your project, you have reached the point where you need to review and understand any and all lessons learned from it. When you perform your project reviews, you need to address certain questions:

• Which choices were correct and incorrect? Why?

• Did you correctly identify risks and assign their probabilities and outcomes? Did you plan your risk responses properly?

• How do the results of your quantitative analysis compare with the actual data? If they are different, why?

Answering these questions during project review is one of the most important steps in the decision analysis process, because it will improve decision-making in the future. Most organizations perform these assessments, either formally or informally.

Unfortunately, not many organizations analyze how they selected their project plan from among the alternatives and determined the probabilities of the risk events. Moreover, few organizations have mechanisms in place to store this information where it can be easily retrieved. Often, the only record of this analysis is stored in the memories of the participants. Given normal staff turnover and the vagaries of human memory, this is a high-risk strategy in itself.

Before we explain how to set up a post-project review process in your organization, let’s examine a number of psychological biases related to project reviews.

How Could We Not Foresee It?

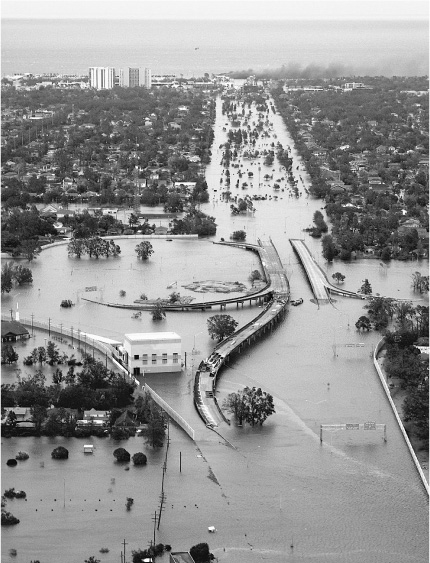

Well before Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans (figure 21-1) in August 2005, there were many predictions of how a hurricane would wreak disaster on the city (Wilson 2001; Fischetti 2001; Mooney 2005). In 2001, the Houston Chronicle published a story that predicted that if a severe hurricane hit New Orleans, it “would strand 250,000 people or more, and probably kill one of 10 left behind as the city drowned under 20 feet of water. Thousands of refugees could land in Houston” (Berger 2001).

Much of New Orleans sits below sea level. To prevent flooding, the city is defended by an extensive levee system. Parts of the system are quite old, and concerns had long been expressed about the system’s ability to withstand the stress that a strong hurricane would impose upon it. Following Hurricane Katrina’s landfall in August 2005, the levees failed in several places. Floodwater from Lake Pontchartrain inundated the city and caused many deaths and billions of dollars in damage. In the aftermath of Katrina, investigations have demonstrated that the levee failures were not caused by natural forces that exceeded the intended design strength. Rather, and alarmingly, the problem lay in the design of the structures, in addition to poor maintenance practices that exacerbated the condition of the levees. It is important to mention that the mechanism of potential levee failure was known years before Hurricane Katrina struck.

The question is, if so many warnings had been raised about potential problems with the levees and the risk of hurricanes, why weren’t more resources invested to improve the levee system? Now, years after the event, these warnings are considered not to be probabilities, but absolute certainties. Before Hurricane Katrina struck, federal, state, and municipal governments and other organizations did not believe that major improvements to the levee system were a main priority. This was because the probability of an event as destructive as Katrina was underestimated, even though a number of experts had warned about the risk. Because the cost of protection against such an extreme event must be juggled with other public priorities, only a limited amount of work to improve the levees was done.

This psychological phenomenon occurs not only in major calamities but in project failures, as well. Often, as we look back at a failed project, we just cannot understand how we did not foresee a catastrophic event when we were given so many warnings. What caused us to ignore those warnings?

In reality, we are experiencing a common psychological phenomenon that occurs when reviewing the results of project decision analysis: after the event, we tend to believe that project failures were more readily foreseeable than was in fact the case.

Figure 21-1. Flooding in Northwest New Orleans and Metairie after Hurricane Katrina (Credit: U.S. Coast Guard, 2005)

In any project there is a chance of failure or a major risk event that can significantly affect it. However, if the probability is deemed small, the project will proceed with risk mitigation in place. Risk mitigation does not mean that the risk will be completely removed, only that the probability of the risk’s occurring and its potential impact will be reduced. Let’s assume that an event occurred and caused major problems. In the aftermath of this event, management will believe that the wrong decision was made. But this is not necessarily true, for the decision could have been correct as long as decision analysis was performed using the most comprehensive information available at the time.

Situations are much more difficult when an unpredicted risk event occurs. Generally, these events were not foreseen because there was incomplete or imperfect data to perform an analysis. However, once an event has occurred, it is impossible to erase any knowledge of the event and to reconstruct the mental processes that occurred before the event.

During the decision process, a lot of irrelevant information must be sorted through (Wohlstetter 1962). Do you recall the movie Tora! Tora! Tora!, which dramatized the events leading up to and during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor? At the start of the movie, several scenes describe the warnings about an impending attack that the military and political leaders received and also the chain of events that led them to underestimate or disregard the threat. After watching this movie, you might wonder how all those people missed so many obvious signs of an impending attack and how so many could get it so terribly wrong. In reality, there were many, many other events occurring at the time that were not shown in the movie. Since we all have 20/20 hindsight, it always becomes clear to us after the fact which information was relevant and which was not. Because of this phenomenon, after a risk event occurs, management tends to believe that it should have been easy to foresee the risk and make the correct decision.

“I Knew It All Along”

Did the decision analysis process help us make better decisions for this particular project? How much more did we learn from the analysis than we already knew? These are very common questions raised by the members of management that approved the decisions.

“I knew it all along,” referred to in psychology as the hindsight bias, is an extremely common psychological bias. Management usually underestimates how much they learned from the decision analysis process. As a result, management tends to undervalue the process—after all, they think, “Why bother with decision analysis if we already know the answer!”

At the project initialization phase, you presented a risk management plan to your manager. One of the risks was a major delay in the delivery of a component. Based on the analysis, you believed it was a critical risk, and in response you created a mitigation plan for it—purchase the component from another vendor. Your manager was not so sure, but agreed to include it in the project plan. Sure enough, this risk event occurred. Fortunately for the project, you had lined up another vendor in advance, and the project was completed as planned. When you have your project review, your manager (who now possesses 20/20 hindsight) notes that the fact that the component delivery risk was critical was obvious, regardless of your risk analysis. He goes further, questioning the value of your quantitative analysis, as this was something he says he intuitively knew. Next time, the manager may not give you an opportunity to do another analysis.

Once an event occurs, many people, not just decision-makers, tend to exaggerate how much probability they had lent to the event’s occurring. Before it occurred, they might have thought the probability was 15%, but afterward they will probably confess that they were 99% sure that the event would occur.

Overestimating the Accuracy of Past Judgments

The two previous biases that we discussed affect managers when they try to evaluate project decisions. Yet project managers or analysts who perform the analysis are not immune from similar biases. In particular, both tend to overestimate the accuracy of past judgments.

Here is a small psychological experiment you can perform in your organization: ask a project manager to re-create, from memory, a risk list or risk breakdown structure he or she defined during a project initialization phase about a year ago. Now compare it with the original risk list. You will most likely find that in the new list the probabilities for risks that actually occurred are much higher than they were in the original list.

The knowledge of outcomes affects our memory of previous analyses. When analysts know the outcome, they will believe that they properly identified the event and assigned the correct probability. The more time that has passed since the original decision analysis was conducted, the greater the effect of this bias.

The Peak-End Rule

One curious heuristic is the peak-end rule, in which we judge our past experiences almost entirely on how they were at their peak (whether pleasant or unpleasant) and how they ended (Kahneman et al. 1999). When we do this, we discard other information, including net pleasantness or unpleasantness and how long the experience lasted. This heuristic affects project reviews because many project stakeholders remember only certain project details. You may recall the product launch itself (the first stage of the project) along with some highlights during the project (like the CEO’s visit and a subsequent dinner in a good restaurant), but you probably don’t remember why, how, and by whom certain choices were made.

The PMBOK Guide recommends identifying lessons learned at any point in the project. In other words, it recommends that you collect and record information about all major project decisions and events at all stages of the project. This helps to mitigate memory errors associated with the peak-end rule.

The Process of Reviewing Decisions

Actual project reviews or retrospectives are usually performed as part of other business processes. The PMBOK Guide recommends creating an organizational corporate knowledge base, which should include a “historical information and lessons learned knowledge base.” This information is collected during the project execution. The Closing Project process includes the Updates of Organizational Process Assets procedure, where “historical information and lessons learned information are transferred to the lessons learned knowledge base for use by future projects.” In practical terms, this means that the results of project reviews should be saved in an organization’s knowledge base so they can be referenced when planning future projects.

In software development processes, such as the Rational Unified Process (RUP) (Kruchten 2003), reviews help to determine whether the established goal was achieved. Such reviews or retrospectives include people, processes, and tools and can be performed after each project iteration. A similar process of reviewing project decisions is called project retrospectives (Kerth 2001). In retrospective, the entire team meets to review what the project goals were, what actually happened during the project, why it happened, and how to improve related processes going forward.

Certain steps should be taken to capture information that is necessary to evaluate project decision-making:

1. Assess input information that was created at the project planning stage:

• Project schedules

• Risk-management plans, including risk breakdown structures with assigned probabilities of certain events

• Strategy tables and other information used to select alternatives

• Results of quantitative analysis

2. Compare input information with actual data:

• Was the selected alternative correct?

• Which events occurred, and which did not?

• Were duration and cost estimates accurate?

3. Briefly document the conclusions, and store the document in a corporate knowledge base.

Corporate Knowledge Base

An organizational knowledge base is a repository, either paper or electronic, where one can find historical information about decisions, as well as lessons learned, in previous projects. How would a knowledge base work in reality?

In one engineering company, we met with a very interesting person. He was about 75 years old and had worked his entire life in the same organization. He probably had been working there for 50 years, serving in many different positions. Fresh out of college, he accepted a position as a junior engineer, and eventually he rose to become head of his department. For the last 20 years, he had worked as a full-time internal consultant to the various divisions in the company. Primarily, he himself was valued as the corporate “knowledge base.”

Although he was not able to generate new engineering ideas, this individual’s long-term memory was excellent. When asked, he analyzed each project to learn if there were any historical precedents that could be applicable. He looked to see if somebody had been faced with similar issues and what the results of their decisions were. By drawing on this knowledge, he was able to make some fairly accurate judgments about the actual probability of certain events.

While that human knowledge base seemed to work fine for the engineering company, human memory always has some limitations. First of all, it is hard to find a person or a group of people who have the capacity to remember and understand all relevant previous projects. Second, everyone has cognitive and motivational biases that can affect their judgment about previous decisions.

Fortunately, a number of computer tools are available to help establish a company’s knowledge base. Some of them are specifically designed for organizational knowledge bases, and many portfolio management software products have document management functionalities, as well.

Not all companies have corporate portfolio management software, and not all companies would choose to store documents related to decision analysis, even if it had the software to do so. Here is a simple and effective way to establish a corporate knowledge base: save all your documents on a corporate intranet in such a way that they can be searched using search tools like Google. These tools can be used effectively in internal sites where you can search your internal archives. Just make sure you use proper keywords for your documents so that the search tool can return the most relevant documents.