7

Management Support

7.0 INTRODUCTION

As we saw in Chapter 6, senior managers are the architects of corporate culture. They are charged with making sure that their companies’ cultures, once accepted, do not come apart. Visible management support is essential to maintaining a project management culture. And above all, the support must be continuous rather than sporadic.

This chapter examines the importance of management support in the creation and maintenance of project management cultures. Case studies illustrate the vital importance of employee empowerment and the project sponsor’s role in the project management system.

7.1 VISIBLE SUPPORT FROM SENIOR MANAGERS

As project sponsors, senior managers provide support and encouragement to the project managers and the rest of the project team. Companies excellent in project management have the following characteristics:

- Senior managers maintain a hands-off approach, but they are available when problems come up.

- Senior managers expect to be supplied with concise project status information, either in a written report format or using dashboards.

- Senior managers practice empowerment.

- Senior managers decentralize project authority and decision making.

- Senior managers expect project managers and their teams to suggest both alternatives and recommendations for solving problems, not just identify the problems.

However, there is a fine line between effective sponsorship and overbearing sponsorship. Robert Hershock, former vice president at 3M, said it best during a videoconference on excellence in project management:

Probably the most important thing is that they have to buy in from the top. There has to be leadership from the top, and the top has to be 100 percent supportive of this whole process. If you’re a control freak, if you’re someone who has high organizational skills and likes to dot all the i’s and cross all the t’s, this is going to be an uncomfortable process, because basically it’s a messy process; you have to have a lot of fault tolerance here. But what management has to do is project the confidence that it has in the teams. It has to set the strategy and the guidelines and then give the teams the empowerment that they need in order to finish their job. The best thing that management can do after training the team is get out of the way.

To ensure their visibility, senior managers need to believe in walk-the-halls management. In this way, every employee will come to recognize the sponsor and realize that it is appropriate to approach the sponsor with questions. Walk-the-halls management also means that executive sponsors keep their doors open. It is important that everyone, including line managers and their employees, feels supported by the sponsor. Keeping an open door can occasionally lead to problems if employees attempt to go around lower-level managers by seeking a higher level of authority. But such instances are infrequent, and the sponsor can easily deflect the problems back to the appropriate manager.

7.2 PROJECT SPONSORSHIP

Executive project sponsors provide guidance for project managers and project teams. They are also responsible for making sure that the line managers who lead functional departments fulfill their resource commitments to the projects under way. In addition, executive project sponsors maintain communication with customers and stakeholders.

The project sponsor usually is an upper-level manager who, in addition to his or her regular responsibilities, provides ongoing guidance to assigned projects. An executive might take on sponsorship for several concurrent projects. Sometimes, on lower-priority or maintenance projects, a middle-level manager may take on the project sponsor role. One organization I know of even prefers to assign middle managers instead of executives. The company believes this avoids the common problem of lack of line manager buy-in to projects. (See Figure 7-1.)

Figure 7-1. Roles of project sponsor.

Source: Reprinted from H. Kerzner, In Search of Excellence in Project Management (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 1998), p. 159.

In some large, diversified corporations, senior managers do not have adequate time to invest in project sponsorship. In such cases, project sponsorship falls to the level below corporate senior management or to a committee.

Some projects do not need project sponsors. Generally, sponsorship is required on large, complex projects involving a heavy commitment of resources. Large, complex projects also require a sponsor to integrate the activities of the functional lines, to dispel disruptive conflicts, and to maintain strong customer and stakeholder relations.

Consider one example of a project sponsor’s support for a project. A project manager who was handling a project in an organization in the federal government decided that another position would be needed on his team if the project were to meet its completion deadline. He had already identified a woman in the company who fit the qualifications he had outlined. But adding another full-time-equivalent position seemed impossible and was beyond his authority. The size of the government project office was constrained by a unit-manning document that dictated the number of positions available.

The project manager went to the project’s executive sponsor for help. The executive sponsor worked with the organization’s human resources and personnel management department to add the position requested. Within 30 days, the addition of the new position was approved. Without the sponsor’s intervention, it would have taken the organization’s bureaucracy months to approve the position, too late to affect the deadline.

In another example, the president of a medium-size manufacturing company wanted to fill the role of sponsor on a special project. The project manager decided to use the president to the project’s best advantage. He asked the president/sponsor to handle a critical situation. The president/sponsor flew to the company’s headquarters and returned two days later with an authorization for a new tooling the project manager needed. The company ended up saving time on the project, and the project was completed four months earlier than originally scheduled.

Sponsorship by Committee

As companies grow, it sometimes becomes impossible to assign a senior manager to every project, and so committees act in the place of individual project sponsors. In fact, the recent trend has been toward committee sponsorship in many kinds of organizations. A project sponsorship committee usually is made up of a representative from every function of the company: engineering, marketing, and production. Committees may be temporary, when a committee is brought together to sponsor one time-limited project, or permanent, when a standing committee takes on the ongoing project sponsorship of new projects.

For example, General Motors Powertrain had achieved excellence in using committee sponsorship. Two key executives, the vice president of engineering and the vice president of operations, led the Office of Products and Operations, a group formed to oversee the management of all product programs. This group demonstrated visible executive-level program support and commitment to the entire organization. The roles and responsibilities of the group were to:

- Appoint the project manager and team as part of the charter process

- Address strategic issues

- Approve the program contract and test for sufficiency

- Assure program execution through regularly scheduled reviews with program managers

Committee governance is now becoming commonplace. Companies that focus on maximizing the business value from a portfolio of strategic projects use committee governance rather than single project sponsorship. The reason for this is that projects are now becoming larger and more complex to the point where a single individual may not be able to make all of the necessary decisions to support a project manager.

Unfortunately, committee governance come with some issues. Many of the people assigned to these governance committees may never have served on governance committees before and may be under the impression that committee governance for projects is the same as organizational governance. To make matters worse, some of the people may never have served as project managers and may not recognize how their decisions impact project management. Governance committee members can inflict a great deal of pain on the portfolio of projects if they lack a cursory understanding of project management. Organizations that are heavy users of agile and Scrum practices use committee governance, and, in most organizations, committee members have a good understanding of their new roles and responsibilities.

Phases of Project Sponsorship

The role of the project sponsor changes over the life cycle of a project. During the planning and initiation phases, the sponsor plays an active role in the following activities:

- Helping the project manager establish the objectives of the project

- Providing guidance to the project manager during the organization and staffing phases

- Explaining to the project manager what environmental or political factors might influence the project’s execution

- Establishing the project’s priority (working alone or with other company executives) and then informing the project manager about the project’s priority in the company and the reason that priority was assigned

- Providing guidance to the project manager in establishing the policies and procedures for the project

- Functioning as the contact point for customers and clients

During the execution phase of a project, the sponsor must be very careful in deciding which problems require his or her guidance. Trying to get involved with every problem that comes up on a project will result in micromanagement. It will also undermine the project manager’s authority and make it difficult for the executive to perform his or her regular responsibilities.

For short-term projects of two years or less, it is usually best that the project sponsor assignment is not changed over the duration of the project. For long-term projects of five years, more or less, different sponsors could be assigned for every phase of the project, if necessary. Choosing sponsors from among executives at the same corporate level works best, since sponsorship at the same level creates a “level” playing field, whereas favoritism can occur at different levels of sponsorship.

Project sponsors need not come from the functional area where the majority of the project work will be completed. Some companies even go so far as assigning sponsors from line functions that have no vested interest in the project. Theoretically, this system promotes impartial decision making.

Customer Relations

The role of executive project sponsors in customer relations depends on the type of organization (entirely project-driven or partially project-driven) and the type of customer (external or internal). Contractors working on large projects for external customers usually depend on executive project sponsors to keep the clients fully informed of progress on their projects. Customers with multimillion-dollar projects often keep an active eye on how their money is being spent. They are relieved to have an executive sponsor they can turn to for answers.

It is common practice for contractors heavily involved in competitive bidding for contracts to include both the project manager’s and the executive project sponsor’s resumes in proposals. All things being equal, the resumes may give one contractor a competitive advantage over another.

Customers prefer to have a direct path of communication open to their contractors’ executive managers. One contractor identified the functions of the executive project sponsor as:

- Actively participating in the preliminary sales effort and contract negotiations

- Establishing and maintaining high-level client relationships

- Assisting project managers in getting the project underway (planning, staffing, etc.)

- Maintaining current knowledge of major project activities

- Handling major contractual matters

- Interpreting company policies for project managers

- Helping project managers identify and solve significant problems

- Keeping general managers and client managers advised of significant problems with projects

Decision Making

Imagine that project management is like car racing. A yellow flag is a warning to watch out for a problem. Yellow flags require action by the project manager or the line manager. There is nothing wrong with informing an executive about a yellow-flag problem as long as the project manager is not looking for the sponsor to solve the problem. Red flags, however, usually do require the sponsor’s direct involvement. Red flags indicate problems that may affect the time, cost, and performance parameters of the project. So red flags need to be taken seriously, and decisions need to be made collaboratively by the project manager and the project sponsor.

Serious problems sometimes result in serious conflicts. Disagreements between project managers and line managers are not unusual, and they require the thoughtful intervention of the executive project sponsor. First, the sponsor should make sure that the disagreement could not be solved without his or her help. Second, the sponsor needs to gather information from all sides and reflect on the alternatives being considered. Then the sponsor must decide whether he or she is qualified to settle the dispute. Often disputes are of a technical nature and require someone with the appropriate knowledge base to solve them. If the sponsor is unable to solve the problem, he or she will need to identify another source of authority that has the needed technical knowledge. Ultimately, a fair and appropriate solution can be shared by everyone involved. If there were no executive sponsor on the project, the disputing parties would be forced to go up the line of authority until they found a common superior to help them. Having executive project sponsors minimizes the number of people and the amount of time required to settle work disputes.

Strategic Planning

Executives are responsible for performing the company’s strategic planning, and project managers are responsible for the operational planning on their assigned projects. Although the thought processes and time frames are different for the two types of planning, the strategic planning skills of executive sponsors can be useful to project managers. For projects that involve process or product development, sponsors can offer a special kind of market surveillance to identify new opportunities that might influence the long-term profitability of the organization. Furthermore, sponsors can gain a lot of strategically important knowledge from lower-level managers and employees. Who else knows better when the organization lacks the skill and knowledge base it needs to take on a new type of product? When the company needs to hire more technically skilled labor? What technical changes are likely to affect the industry?

7.3 EXCELLENCE IN PROJECT SPONSORSHIP

In excellent companies, the role of the sponsor is not to supervise the project manager but to make sure that the best interests of both the customer and the company are recognized. However, as the next two examples reveal, it is seldom possible to make executive decisions that appease everyone.

Franklin Engineering (a pseudonym) had a reputation for developing high-quality, innovative products. Unfortunately, the company paid a high price for its reputation: a large research and development (R&D) budget. Fewer than 15 percent of the projects initiated by R&D led to the full commercialization of a product and the recovery of the research costs.

The company’s senior managers decided to implement a policy that mandated that all R&D project sponsors periodically perform cost–benefit analyses on their projects. When a project’s cost–benefit ratio failed to reach the levels prescribed in the policy, the project was canceled for the benefit of the whole company.

Initially, R&D personnel were unhappy to see their projects canceled, but they soon realized that early cancellation was better than investing large amounts in projects that were likely to fail. Eventually, project managers and team members came to agree that it made no sense to waste resources that could be better used on more successful projects. Within two years, the organization found itself working on more projects with a higher success rate but no addition to the R&D budget.

Another disguised case involves a California-based firm that designs and manufactures computer equipment. Let’s call the company Design Solutions. The R&D group and the design group were loaded with talented individuals who believed that they could do the impossible, and often did. These two powerful groups had little respect for the project managers and resented schedules because they thought schedules limited their creativity.

The company introduced two new products it onto the market barely ahead of the competition. The company had initially planned to introduce them a year earlier. The reason for the late releases: Projects had been delayed because of the project teams’ desire to exceed the specifications required, not just meet them.

To help the company avoid similar delays in the future, the company decided to assign executive sponsors to every R&D project to make sure that the project teams adhered to standard management practices in the future. Some team members tried to hide their successes with the rationale that they could do better. But the sponsor threatened to dismiss those employees, and they eventually relented.

The lessons in both cases are clear. Executive sponsorship actually can improve existing project management systems to better serve the interests of the company and its customers.

7.4 THE NEED FOR A PROJECT CANCELLATION CRITERIA

Not all projects will be successful. Executives must be willing to establish an “exit criteria” that indicates when a project should be terminated. If the project is doomed to fail, then the earlier it is terminated, the sooner valuable resources can be reassigned to projects that demonstrate a higher likelihood of success. Without cancellation criteria, perhaps even identified in the project’s business case, there is a risk that projects will linger on while squandering resources.

As an example, two vice presidents came up with ideas for pet projects and funded the projects internally using money from their functional areas. Both projects had budgets close to $2 million and schedules of approximately one year. These were somewhat high-risk projects because both required that a similar technical breakthrough be made. No cancellation criteria were established for either project. There was no guarantee that the technical breakthrough could be made at all. And even if the technical breakthrough could be made, both executives estimated that the shelf life of both products would be about one year before becoming obsolete, but they believed they could easily recover their R&D costs.

These two projects were considered pet projects because they were established at the personal request of two senior managers and without any real business case. Had these two projects been required to go through the formal portfolio selection of projects process, neither one would have been approved. The budgets for these projects were way out of line for the value that the company would receive, and the return on investment would be below minimum levels even if the technical breakthrough could be made. The project management office (PMO), which is actively involved in the portfolio selection of projects process, also stated that it would never recommend approval of a project where the end result would have a shelf life of one year or less. Simply stated, these projects existed for the self-satisfaction of the two executives and to get them prestige from their colleagues.

Nevertheless, both executives found money for their projects and were willing to let them go forward without the standard approval process. Each executive was able to get an experienced project manager from their group to manage their pet project.

At the first gate review meeting, both project managers stood up and recommended that their projects be canceled and that the resources be assigned to other, more promising projects. They both stated that the technical breakthrough needed could not be made in a timely manner. Under normal conditions, both of these project managers would have received medals for bravery in standing up and recommending that their project be canceled. This certainly appeared as a recommendation in the best interest of the company.

But both executives were not willing to give up that easily. Canceling both projects would be humiliating for the executives who were sponsoring the projects. Instead, both executives stated that their project was to continue on to the next gate review meeting at which time a decision would be made regarding possible cancellation.

At the second gate review meeting, both project managers once again recommended that their projects be canceled. And as before, both executives asserted that the projects should continue to the next gate review meeting before a decision would be made.

As luck would have it, the necessary technical breakthrough was finally made, but six months late. That meant that the window of opportunity to sell the products and recover the R&D costs would be six months rather than one year. Unfortunately, the marketplace knew that these products might be obsolete in six months, and very few sales occurred of either product.

Both executives had to find a way to save face and avoid the humiliation of having to admit that they squandered a few million dollars on two useless R&D projects. This could very well impact their year-end bonuses. The solution that the executives found was to promote the project managers for creating the products and then blame marketing and sales for not finding customers.

Exit criteria should be established during the project approval process, and the criteria should be clearly visible in the project’s business case. The criteria can be based on time to market, cost, selling price, quality, value, safety, or other constraints. If this is not done, the example just given can repeat itself again and again.

7.5 HEWLETT-PACKARD SPONSORSHIP IN ACTION

According to Doug Bolzman, consultant architect, PMP, ITIL Expert at HP:

Management supports the results of project management, and if the PMO is in a position to understand the current environment and how to improve the results, management will listen. If management is given a problem statement regarding how projects are not being managed effectively, then [the reports] will be of little value.

We share a story of when a fellow business associate came to us and asked why our Release Management Methodology was not formally implemented across the organization as a corporate method. This sponsor of ours had connections and scheduled a meeting with the chief information officer (CIO) of our company. (This was a few years after the turn of the century.) We presented the overall methodology, the value to the organization, the success stories of what we achieved. His response was “This is all fine and good, but what do you want me to do?” The sponsor of this meeting fell back into his chair and replied: “We are looking for ‘management commitment’ for this methodology.” As the meeting concluded, I realized that if it were not for the good meal we had the night before after we flew into headquarters, the meeting would have been a total loss. The point to be made here is that we did not define what specifically we were looking for from the management team. Now when we are in the same situation, we explain the investments, the funding, the resource needs, the cultural change, and the policies that they need to sanction and enforce. We describe their role and responsibilities for supporting the project, the practice, the PMO, or whatever we are looking for them to support.

7.6 ZURICH AMERICA INSURANCE COMPANY: IMPROVING STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT

In section 7.6, Kathleen Cavanaugh, PMP, Zurich—ZNA PMO lead, provides us with insight of sponsors may help improve stakeholder engagement. Project lessons learned offer valuable insights into what’s working and not working well within projects/programs. When lessons learned are rolled up to the portfolio level, the common problems faced by these projects/programs are revealed and trends appear that may otherwise have been overlooked.

* * *

One of the improvements opportunities identified from project lessons learned reviews in recent years at Zurich in North America (ZNA) was the need for a new project leadership role called the business lead. The aggregated project feedback showed that on large, transformational projects/programs stronger business engagement was a “must have” from the beginning of the effort all the way through postimplementation. It was also noted that middle layers of management can often pose the biggest alignment challenges for these types of large process- and/or people-related change projects/programs. The need was clear. Stakeholders at all levels must be kept informed, aligned with project goals, and involved in the project/program throughout the life cycle. Without stakeholder commitment and ownership, the project/program will suffer from low acceptance/adoption rates or, worse, may be canceled altogether.

So, to help solve this problem, leaders from across the business worked to define the responsibilities in order to bring the business lead role to life. The role was first piloted to help prove the concept and to gain agreement prior to rollout. Guidelines were provided to help clarify the business lead responsibilities, which originally included: aligning stakeholders, ensuring project goals continually support the business strategy, utilizing change management to prepare stakeholders for project impacts, ensuring postimplementation support and benefits realization. However, the actual duties of the business lead are ultimately determined by the project sponsor and may vary from project to project.

The role itself was designed to complement and collaborate with the project sponsor and project lead roles creating a project leadership team triangle. Together they form a strong partnership and join forces to make key decisions for the project/program. The project lead and business lead often work closely together throughout the project/program connecting the business and information technology (IT) worlds. To help ensure stakeholders stay engaged, a variety of methods may be used, including focus group meetings, user councils, and multiple feedback mechanisms. Middle management should be a focal point for project/program communications since these are the people who can ensure end users hear and understand key messages. The sponsor provides continual oversight and guidance for the project/program. If the project/program hits a roadblock, the escalation path usually goes straight to the sponsor and/or steering committee for resolution.

To be effective, the person filling the business lead role needs to be someone at a fairly high level in the organization, and they must possess a unique blend of skills . . . skills that include cross-functional knowledge, the ability to challenge the status quo and break down barriers and unite stakeholders. The role itself inherently calls for the chosen one to be strong in the art of change management and communication. But for this person to be truly successful, he/she must be allowed to devote himself/herself to the project/program especially on large, cross-functional efforts. We often find the role requires heavy involvement in the day-to-day activities of the project/program. So, in many cases the selected business lead relinquishes current duties for at least 12 to 18 months in order to become officially 100 percent dedicated to this key project/program role. Convincing leadership to take someone out of a role and to dedicate them to a large transformational effort for this amount of time is not always an easy task. But, if the project/program is truly important to the organization, then it’s a small price to pay to help ensure a successful implementation. It is a big decision to make and one that is usually driven by the sponsor who has the organizational awareness and knowledge to identify the right person for the role.

The value of the business lead role has grown significantly over the past couple of years, and a community of practice is being formed so that business leads can share their experiences and lessons learned in order to continue improving their capabilities. The role is becoming a solid cornerstone of the project leadership team for large, transformational projects/programs at ZNA. The collaboration and synergy between the project sponsor, project lead, and business lead roles is the key to their success. This project leadership structure is proving to be a viable model to help ensure stakeholder engagement and alignment throughout the project/program life cycle, which translates to more successful results and improved end user satisfaction.

7.7 PROJECT GOVERNANCE

All projects have the potential of getting into trouble, but, in general, project management can work well as long as the project’s requirements do not impose severe pressure on the project manager and a project sponsor exists as an ally to assist the project manager when trouble does appear. Unfortunately, in today’s chaotic environment, this pressure appears to be increasing because:

- Companies are accepting high-risk and highly complex projects as a necessity for survival.

- Customers are demanding low-volume, high-quality products with some degree of customization.

- Project life cycles and new product development times are being compressed.

- Enterprise environmental factors are having a greater impact on project execution.

- Customers and stakeholders want to be more actively involved in the execution of projects.

- Companies are developing strategic partnerships with suppliers, and each supplier can be at a different level of project management maturity.

- Global competition has forced companies to accept projects from customers that are all at a different levels of project management maturity and with different reporting requirements.

These pressures tend to slow down the decision-making processes at a time when stakeholders want the projects and processes to be accelerated. One person, while acting as the project sponsor, may have neither the time nor the capability to address all of these additional issues. The resulting project slowdown can occur because:

- The project manager is expected to make decisions in areas where he/she has limited knowledge.

- The project manager hesitates to accept full accountability and ownership for the projects.

- Excessive layers of management are superimposed on top of the project management organization.

- Risk management is pushed up to higher levels in the organization hierarchy, resulting in delayed decisions.

- The project manager demonstrates questionable leadership ability on some nontraditional projects.

The problems resulting from these pressures may not be able to be resolved, at least easily and in a timely manner, by a single project sponsor. These problems can be resolved using effective project governance. Project governance is actually a framework by which decisions are made. Governance relates to decisions that define expectations, accountability, responsibility, the granting of power or verifying performance. Governance relates to consistent management, cohesive policies, processes, and decision-making rights for a given area of responsibility. Governance enables efficient and effective decision making to take place.

Every project can have different governance, even if each project uses the same enterprise project management methodology. The governance function can operate as a separate process or as part of project management leadership. Governance is not designed to replace project decision making but to prevent undesirable decisions from being made.

Historically, governance was provided by a single project sponsor. Today, governance is a committee and can include representatives from each stakeholder’s organization. Table 7-1 shows various governance approaches based on the type of project team. Committee membership can change from project to project and industry to industry. Membership may also vary based on the number of stakeholders and whether the project is for an internal or external client. On long-term projects, membership can change throughout the project.

TABLE 7-1 Types of Project Governance

| Structure | Description | Governance |

| Dispersed locally | Team members can be full time or part time. They are still attached administratively to their functional area. | Usually a single person acts as sponsor but may be an internal committee based on project complexity. |

| Dispersed geographically | This is a virtual team. Project managers may never see some team members. Team members can be full time or part time. | Usually governance by committee and can include stakeholder membership. |

| Colocated | All team members are physically located in close proximity to the project manager. The project manager does not have any responsibility for wage and salary administration. | Usually a single person acting as the sponsor. |

| Projectized | This is similar to a colocated team, but the project manager generally functions as a line manager and may have wage and salary responsibilities. | May be governance by committee, based on project size and number of strategic partners. |

Governance on projects and programs sometimes fails because people confuse project governance with corporate governance. The result is that members of the committee are not sure what their role should be. Some of the major differences include:

- Alignment. Corporate governance focuses on how well the portfolio of projects is aligned to and satisfies overall business objectives. Project governance focuses on ways to keep a project on track.

- Direction. Corporate governance provides strategic direction with a focus on how project success will satisfy corporate objectives. Project governance is more operation direction with decisions based on predefined parameters on project scope, time, cost, and functionality.

- Dashboards. Corporate governance dashboards are based on financial, marketing, and sales metrics. Project governance dashboards have operations metrics on time, cost, scope, quality, action items, risks, and deliverables.

- Membership. Corporate governance committees are composed of the seniormost levels of management. Project government membership may include some members from middle management.

Another reason why failure may occur is that members of the project or program governance group do not understand project or program management. This can lead to micromanagement by the governance committee. There is always the question of what decisions must be made by the governance committee and what decisions the project manager can make. In general, the project manager should have the authority for decisions related to actions necessary to maintain the baselines. Governance committees must have the authority to approve scope changes above a certain dollar value and to make decisions necessary to align the project to corporate objectives and strategy.

7.8 TOKIO MARINE: EXCELLENCE IN PROJECT GOVERNANCE1

Executive Management Must Establish IT Governance: Tokio Marine Group

Section 7.8 contributed by Yuichi (Rich) Inaba, CISA, and Hiroyuki Shibuya. Yuichi Inaba is a senior consultant specialist in the area of IT governance, IT risk management and IT information security in the Tokio Marine and Nichido Systems Co. Ltd. (TMNS), a Tokio Marine Group company. Before transferring to TMNS, he had worked in the IT Planning Dept. of Tokio Marine Holdings Inc. and had engaged in establishing Tokio Marine Group’s IT governance framework based on COBIT 4.1. His current responsibility is to implement and practice Tokio Marine Group’s IT governance at TMNS. Inaba is a member of the ISACA Tokyo Chapter’s Standards Committee and is currently engaged in translating COBIT 5 publications in Japanese.

Hiroyuki Shibuya is an executive officer in charge of IT at Tokio Marine Holdings Inc. From 2000 to 2005, he led the innovation project from the IT side, which has totally reconstructed the insurance product lines, their business processes, and the information systems of Tokio Marine and Nichido Fire Insurance Co. Ltd. To leverage his experience from this project as well as remediate other troubled development projects of group companies, he was named the general manager of the newly established IT planning department at Tokio Marine Holdings in July 2010. Since then, he has been leading the efforts to establish IT governance basic policies and standards to strengthen IT governance throughout the Tokio Marine Group.

* * *

Tokio Marine Group is a global corporate group engaged in a wide variety of insurance businesses. It consists of about 70 companies on five continents, including Tokio Marine and Nichido Fire Insurance (Japan), Philadelphia Insurance (US), Kiln (UK), and Tokio Marine Asia (Singapore).

In addition to Tokio Marine and Nichido Fire Insurance, which is the largest property and casualty insurance company in Japan, Tokio Marine Group has several other domestic companies in Japan, such as Tokio Marine and Nichido Life Insurance Co. Ltd, as well as service providers, such as Tokio Marine and Nichido Medical Service Co. Ltd. and Tokio Marine and Nachido Facilities Inc.

Implementing IT Governance at Tokio Marine Group

Tokio Marine Holdings, which is responsible for establishing the group’s IT governance approach, observed that the executive management of Tokio Marine Group companies believes that IT is an essential infrastructure for business management, and it hoped to strengthen company management by utilizing IT. However, some directors and executives had a negative impression of IT—that IT is difficult to understand, costs too much, and results in frequent system troubles and system development failures.

It is common for an organization’s executive management to recognize the importance of system development but to put its development solely on the shoulders of the IT department. Other executives go even further, saying that the management or governance of IT is not anyone’s business but the IT department’s or CIO’s. This line of thinking around IT is similar to the thought process that accounting is the job of the accounting department and handling personnel affairs is the role of the human resources department.

These are typical behaviors of organizations that fail to implement IT governance systems. Tokio Marine Holdings’ executive management recognized that IT is not for IT’s sake alone but is a tool to strengthen business.

Tokio Marine Holdings’ management recognized that there were various types of system development failures (e.g., development delays for the service-in date, projects being over budget). Even more frequently, the organization was finding requirement gaps—for instance, where after building a system, the business people say, “This is not the system that we asked you to build” or “The system that you built is not easy to use. It is useless for the business.”

Why the Requirement Gaps Occur

The process of system development is similar to that of a buildings construction. However, there is a distinct difference between the two: system development is not visible, whereas building construction is. Therefore, in system development, it is inevitable that there are recognition and communication gaps between business and IT.

Tokio Marine Group’s Solution for System Development Success

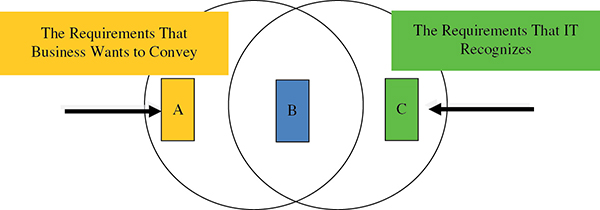

To fill these gaps, business and IT must communicate enough to minimize the gaps between A and C in Figure 7-2 and maximize a common understanding of B. The road to success for system development is to improve the quality of communication between business and IT.

Figure 7-2. The requirements gap.

Such communication cannot be reached or maintained in a one-sided relationship. Ideal communication is enabled only with an equal partnership between business and IT with appropriate roles and responsibilities mutually allocated.

This is the core concept of Tokio Marine Group’s Application Owner System.

Implementing the Application Owner System

Tokio Marine Holdings decided to implement the Application Owner System as a core concept of the Group It Governance System. Tokio Marine Holdings believes it is essential for the group’s companies to succeed in system development and to achieve the group’s growth in the current business environment.

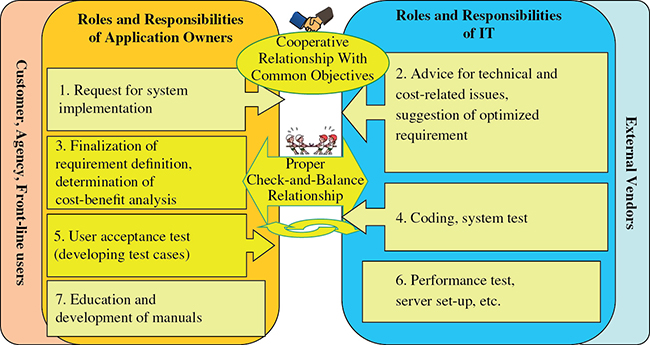

The basic idea of the Application Owner System (Figure 7-3) is:

- Mutual cooperation between business and IT with proper check-and-balance functions, appropriately allocated responsibilities and shared objectives.

- Close communication between business and IT, each taking their own respective roles and responsibilities into account.

Figure 7-3. The Application Owner System in Tokio Marine Group.

Early Success in Tokio Marine and Nichido Fire Insurance

Tokio Marine and Nichido Fire Insurance Co. Ltd., the largest group company, implemented the Application Owner System in 2000. Implementation of the Application Owner System immediately reduced system troubles and problems by 80 percent. (See Figure 7-4.)

Figure 7-4. Number of system troubles.

Mind-Set of IT

Tokio Marine’s mind-set is that only executive management can establish the enterprise’s IT governance system. Thus, IT governance is the responsibility of executive management.

Furthermore, the organization is of the mind-set that all employees, not only executive management, should understand the principle that strong IT systems cannot be realized by the IT department alone but require cooperation between business and IT. It is important that all employees recognize IT matters as their own, not as the matter of the IT function.

Establishing such a mind-set within the enterprise is a role of the executive management.

Tokio Marine Group’s IT Governance System

Characterized by the Application Owner System, Tokio Marine Holdings has introduced an IT governance framework, focused on the COBIT 4.1 framework, specifically the Plan and Organize (PO) domain.

The main goals of the IT Governance Framework are:

- Establishing basic policies for IT governance. Tokio Marine Holdings established the Basic Policies for IT Governance as the policies for the group’s IT governance framework.

- Establishing guiding principles for IT governance. Tokio Marine Holdings defines seven principles as the guiding principles. (See Table 7-2.) These cover the five focus areas defined in the Board Briefing on IT Governance, particularly focusing on strategic alignment and value delivery. The seven principles are included in the Basic Policies for IT Governance. Tokio Marine Holdings thinks that the most important principle is the Application Owner System, which is stated as follows:

In implementing the plan, it is important for the IT unit and the application owner units to cooperate with each other with proper checks and balance functions. Management shall clearly determine the appropriate sharing of roles between the IT unit and application owner units, secure human resources of adequate quality in both units, and establish a management system to assure that each unit will execute the plan according to its responsibilities.

- Establishing a governance and management system for Tokio Marine Group. Tokio Marine Holdings defines the governance and management system to be implemented in the group companies. It covers five domains and consists of three major components: establishment of the organizational structure; establishment of policies and standards; and execution of the plan, do, check, and act (PCDA) cycle for improvement. The governance and management system required for Tokio Marine Group companies is detailed in the Group IT Governance Standard.

- Establishing an IT governance standard (the definition of Tokio Marine’s priority processes). Tokio Marine Holdings has decided to utilize COBIT 4.1 to define the management system. However, the organization recognizes that it is difficult for a relatively small group of companies to implement mature processes for all COBIT 4.1 processes. To handle this concern, the organization focused on the minimal set and processes or more detailed control on objectives, which are essential for its group business in terms of IT governance and the most important controls for Tokio Marine Group.

TABLE 7-2 Seven Guiding Principles

| No. | Guiding Principles | Focus Area |

| 1 | Establish an IT strategic plan that enables management to achieve its business strategic plan, build the business processes for it, and develop an execution plan. | Strategic Alignment |

| 2 | In executing the plan, ensure that the IT unit and the application owner units cooperate with each other with proper check-and-balance functions. | Strategic Alignment |

| 3 | In the development or implementation of information systems, ensure that management scrutinizes the validity of the project plan from the standpoint of quality assurance, usability, commitment to service-in date, appropriate cost estimation, and matching to the human resources availability. | Value Delivery |

| 4 | Ensure that the information systems are fully utilized by all staff in the company in order to achieve the objectives for the development or implementation of the information systems. | Value Delivery |

| 5 | Conduct appropriate IT resource management, including computer capacity management and human resources management. | Resource Management |

| 6 | Conduct appropriate risk management and information security management, and establish contingency plans for system faults in consideration of the accumulation of various risk factors in IT, such as high dependency of business processes on IT, centralization of important information, and threats from wider use of the Internet. | Risk Management |

| 7 | Encourage the transparency of IT operations to be improved, and monitor their progress, which includes, for example, the progress of projects, the usage of IT resources, and utilization of information systems. | Performance Measurement |

In the IT Governance Standard, Tokio Marine Holdings defined the IT controls outlined in Figure 7-5 as priorities for the Tokio Marine Group. The priority IT controls are defined as five domains, 14 processes, and 39 control objectives, which are selected processes from the 210 control objectives of COBIT 4.1. (See Table 7-3.)

Figure 7-5. Tokio Marine group’s priority controls.

TABLE 7-3 Tokio Marine Group’s Priority Controls

| Domain Name | Id | Process Name | |

| a. | Planning and | a1 | Annual IT planning |

| organization | a2 | Definitions of roles and responsibilities of the IT unit and application owner units | |

| a3 | Establishment of an IT steering committee | ||

| b. | Projects management | b1 | Management of development and implementation projects |

| c. | Change management | c1 | Change control |

| d. | Operations | d1 | Incident/problem management |

| Management | d2 | Vendor management | |

| d3 | Security management | ||

| d4 | IT asset management | ||

| d5 | Computer capacity management | ||

| d6 | Disaster recovery and backup/restore | ||

| e. | Monitoring | e1 | Annual IT review |

| performance and | e2 | Monitoring the IT steering committee | |

| return on investment | e3 | Monitoring project management, change management, and systems operation management |

The group companies are required to improve the priority controls to reach a maturity level 3, according to the COBIT Maturity Model, and report the progress of improvements of Tokio Marine Holdings.

Toward the Future

Since the establishment of the IT governance system for Tokio Marine Group, Tokio Marine Holdings has extensively communicated not only with CIOs but also with CEOs and executive management of the group companies to ensure that they understand, agree on, and take leadership for IT governance implementation.

Through these activities, the organization is confident that the core concept of IT governance has become better understood by management and good progress is being made as a result of the implementation of the Application Owner System in group companies. Tokio Marine Holdings will continue its evangelist mission to the group companies, realizing the benefit for the group business and giving value to stakeholders.

7.9 EMPOWERMENT OF PROJECT MANAGERS

One of the biggest problems with assigning executive sponsors to work beside line managers and project managers is the possibility that the lower-ranking managers will feel threatened with a loss of authority. This problem is real and must be dealt with at the executive level. Frank Jackson, formerly a senior manager at MCI, believes in the idea that information is power:

We did an audit of the teams to see if we were really making the progress that we thought or were kidding ourselves, and we got a surprising result. When we looked at the audit, we found out that 50 percent of middle management’s time was spent in filtering information up and down the organization. When we had a sponsor, the information went from the team to the sponsor to the operating committee, and this created a real crisis in our middle management area.

MCI has found its solution to this problem. If there is anyone who believes that just going and dropping into a team approach environment is an easy way to move, it’s definitely not. Even within the companies that I’m involved with, it’s very difficult for managers to give up the authoritative responsibilities that they have had. You just have to move into it, and we’ve got a system where we communicate within MCI, which is MCI mail. It’s an electronic mail system. What it has enabled us to do as a company is bypass levels of management. Sometimes you get bogged down in communications, but it allows you to communicate throughout the ranks without anyone holding back information.

Not only do executives have the ability to drive project management to success, they also have the ability to create an environment that leads to project failure. According to Robert Hershock, former vice president at 3M:

Most of the experiences that I had where projects failed, they failed because of management meddling. Either management wasn’t 100 percent committed to the process, or management just bogged the whole process down with reports and a lot of other innuendos. The biggest failures I’ve seen anytime have been really because of management. Basically, there are two experiences where projects have failed to be successful. One is the management meddling where management cannot give up its decision-making capabilities, constantly going back to the team and saying you’re doing this wrong or you’re doing that wrong. The other side of it is when the team can’t communicate its own objective. When it can’t be focused, the scope continuously expands, and you get into project creep. The team just falls apart because it has lost its focus.

Project failure can often be a matter of false perceptions. Most executives believe that they have risen to the top of their organizations as solo performers. It is very difficult for them to change without feeling that they are giving up a tremendous amount of power, which traditionally is vested in the highest level of the company. To change this situation, it may be best to start small. As one executive observed:

There are so many occasions where senior executives won’t go to training and won’t listen, but I think the proof is in the pudding. If you want to instill project management teams in your organizations, start small. If the company won’t allow you to do it using the Nike theory of just jumping in and doing it, start small and prove to them one step at a time that they can gain success. Hold the team accountable for results—it proves itself.

It is also important for us to remember that executives can have valid reasons for micromanaging. One executive commented on why project management might not be working as planned in his company:

We, the executives, wanted to empower the project managers and they, in turn, would empower their team members to make decisions as they relate to their project or function. Unfortunately, I do not feel that we (the executives) totally support decentralization of decision making due to political concerns that stem from the lack of confidence we have in our project managers, who are not proactive and who have not demonstrated leadership capabilities.

In most organizations, senior managers start at a point where they trust only their fellow managers. As the project management system improves and a project management culture develops, senior managers come to trust project managers, even though they do not occupy positions high on the organizational chart. Empowerment does not happen overnight. It takes time and, unfortunately, a lot of companies never make it to full project manager empowerment.

7.10 MANAGEMENT SUPPORT AT WORK

Visible executive support is necessary for successful project management and the stability of a project management culture. But there is such a thing as too much visibility for senior managers. Take the following case example, for instance.

Midline Bank

Midline Bank (a pseudonym) is a medium-size bank doing business in a large city in the Northwest. Executives at Midline realized that growth in the banking industry in the near future would be based on mergers and acquisitions and that Midline would need to take an aggressive stance to remain competitive. Financially, Midline was well prepared to acquire other small- and medium-size banks to grow its organization.

The bank’s information technology group was given the responsibility of developing an extensive and sophisticated software package to be used in evaluating the financial health of the banks targeted for acquisition. The software package required input from virtually every functional division of Midline. Coordination of the project was expected to be difficult.

Midline’s culture was dominated by large, functional empires surrounded by impenetrable walls. The software project was the first in the bank’s history to require cooperation and integration among the functional groups. A full-time project manager was assigned to direct the project.

Unfortunately, Midline’s executives, managers, and employees knew little about the principles of project management. The executives did, however, recognize the need for executive sponsorship. A steering committee of five executives was assigned to provide support and guidance for the project manager, but none of the five understood project management. As a result, the steering committee interpreted its role as one of continuous daily direction of the project.

Each of the five executive sponsors asked for weekly personal briefings from the project manager, and each sponsor gave conflicting directions. Each executive had his or her own agenda for the project.

By the end of the project’s second month, chaos took over. The project manager spent most of his time preparing status reports instead of managing the project. The executives changed the project’s requirements frequently, and the organization had no change control process other than the steering committee’s approval.

At the end of the fourth month, the project manager resigned and sought employment outside the company. One of the executives from the steering committee then took over the project manager’s role, but only on a part-time basis. Ultimately, the project was taken over by two more project managers before it was completed, one year later than planned. The company learned a vital lesson: More sponsorship is not necessarily better than less.

Contractco

Another disguised case involves a Kentucky-based company I’ll call Contractco. Contractco is in the business of nuclear fusion testing. The company was in the process of bidding on a contract with the U.S. Department of Energy (DoE). The department required that the project manager be identified as part of the company’s proposal and that a list of the project manager’s duties and responsibilities be included. To impress the DoE, the company assigned both the executive vice president and the vice president of engineering as cosponsors.

The DoE questioned the idea of dual sponsorship. It was apparent to the DoE that the company did not understand the concept of project sponsorship, because the roles and responsibilities of the two sponsors appeared to overlap. The DoE also questioned the necessity of having the executive vice president serve as a sponsor.

The contract was eventually awarded to another company. Contractco learned that a company should never underestimate the customer’s knowledge of project management or project sponsorship.

Health Care Associates

Health Care Associates (another pseudonym) provides health care management services to both large and small companies in New England. The company partners with a chain of 23 hospitals in New England. More than 600 physicians are part of the professional team, and many of the physicians also serve as line managers at the company’s branch offices. The physician-managers maintain their own private clinical practices as well.

It was the company’s practice to use boilerplate proposals prepared by the marketing department to solicit new business. If a client was seriously interested in Health Care Associates’ services, a customized proposal based on the client’s needs would be prepared. Typically, the custom-designed process took as long as six months or even a full year.

Health Care Associates wanted to speed up the custom-designed proposal process and decided to adopt project management processes to accomplish that goal. The company decided that it could get a step ahead of its competition if it assigned a physician-manager as the project sponsor for every new proposal. The rationale was that the clients would be favorably impressed.

The pilot project for this approach was Sinco Energy (another pseudonym), a Boston-based company with 8,600 employees working in 12 cities in New England. Health Care Associates promised Sinco that the health care package would be ready for implementation no later than six months from now.

The project was completed almost 60 days late and substantially over budget. Health Care Associates’ senior managers privately interviewed each of the employees on the Sinco project to identify the cause of the project’s failure. The employees had the following observations:

- Although the physicians had been given management training, they had a great deal of difficulty applying the principles of project management. As a result, the physicians ended up playing the role of invisible sponsor instead of actively participating in the project.

- Because they were practicing physicians, the physician sponsors were not fully committed to their role as project sponsors.

- Without strong sponsorship, there was no effective process in place to control scope creep.

- The physicians had not had authority over the line managers, who supplied the resources needed to complete a project successfully.

Health Care Associates’ senior managers learned two lessons. First, not every manager is qualified to act as a project sponsor. Second, the project sponsors should be assigned on the basis of their ability to drive the project to success. Impressing the customer is not everything.

Indra

According to Enrique Sevilla Molina, PMP, formerly Corporate PMO Director at Indra:

Executive management is highly motivated to support project management development within the company. They regularly insist upon improving our training programs for project managers as well as focusing on the need that the best project management methods are in place.

Sometimes the success of a project constitutes a significant step in the development of a new technology, in the launch in a new market, or for the establishment of a new partnership, and, in those cases, the managing directorate usually plays an especially active role as sponsors during the project or program execution. They participate with the customer in steering committees for the project or the program, and help in the decision making or risk management processes.

For a similar reason, due to the significance of a specific project but at a lower level, it is not uncommon to see middle-level management carefully watching its execution and providing, for instance, additional support to negotiate with the customer the resolution of a particular issue.

Getting middle-level management support has been accomplished using the same set of corporate tools for project management at all levels and for all kind of projects in the company. No project is recognized if it is not in the corporate system, and to do that, the line managers must follow the same basic rules and methods, no matter if it is a recurring, a nonrecurring effort, or other type of project. A well-developed WBS [work breakdown structure], a complete foreseen schedule, a risk management plan, and a tailored set of earned value methods may be applied to any kind of projects.

7.11 GETTING LINE MANAGEMENT SUPPORT

Management support is not restricted to senior management, as the previous section showed. Line management support is equally crucial for project management to work effectively. Line managers are usually more resistant to project management and often demand proof that project management provides value to the organization before they support the new processes. This problem was identified previously in the journey to excellence in project management. It also appeared at Motorola. According to a spokesperson at Motorola, getting line management support “was tough at first. It took years of having PMs provide value to the organization.”

When organizations become mature in project management, sponsorship at the executive levels and at middle management levels becomes minimal and integrated project teams are formed where the integrated or core team is empowered to manage the project with minimal sponsorship other than for critical decisions. These integrated or core teams may or may not include line management. The concept of core teams became a best practice at Motorola:

Most project decisions and authority resides in the project core team. The core team is made up of middle- to low-level managers for the different functional areas (marketing, software, electrical, mechanical, manufacturing, system test, program management, quality, etc.) and has the project ownership responsibility. This core team is responsible for reviewing and approving product requirements and committing resources and schedule dates. It also acts as the project change control board and can approve or reject project scope change requests. However, any ship acceptance date changes must be approved by senior management.

7.12 INITIATION CHAMPIONS AND EXIT CHAMPIONS

As project management evolved, so did the role of the executive in project management. Today, the executive plays three roles:

- Project sponsor

- Project (initiation) champion

- Exit champion

The role of the executive in project management as a project sponsor has become reasonably mature. Most textbooks on project management have sections that are dedicated to the role of the project sponsor.2 The role of the project champion however, is just coming of age. Stephen Markham defines the role of the champion:

Champions are informal leaders who emerge in a somewhat erratic fashion. Championing is a voluntary act by an individual to promote a particular project. In the act of championing, individuals rarely refer to themselves as champions; rather, they describe themselves as trying to do the right thing for the right company. A champion rarely makes a single decision to champion a project. Instead, he or she begins in a simple fashion and develops increasing enthusiasm for the project. A champion becomes passionate about a project and ultimately engages others based upon personal conviction that the project is the right thing for the entire organization. The champion affects the way other people think of the project by spreading positive information across the organization. Without official power or responsibility, a champion contributes to new product development by moving projects forward. Thus, champions are informal leaders who (1) adopt projects as their own in a personal way, (2) take on risk by promoting the projects beyond what is expected of people in their position, and (3) promote the project by getting other individuals to support it.3

With regard to new product development projects, champions are needed to overcome the obstacles in the “valley of death,” as seen in Figure 7-6. The valley of death is the area in new product development where recognition of the idea/invention and efforts to commercialize the product come together. In this area, good projects often fall by the wayside and projects with less value often get added into the portfolio of projects. According to Markham:

Many reasons exist for the Valley of Death. Technical personnel [left side of Figure 7-6] often do not understand the concerns of commercialization personnel [right side] and vice versa. The cultural gap between these two types of personnel manifests itself in the results prized by one side and devalued by the other. Networking and contact management may be important to sales people but seen as shallow and self-aggrandizing by technical people. Technical people find value in discovery and pushing the frontiers of knowledge. Commercialization people need a product that will sell in the market and often consider the value of discovery as merely theoretical and therefore useless. Both technical and commercialization people need help translating research findings into superior product offerings.4

Figure 7-6. Valley of death.

Source: S. K. Markham, “Product Champions: Crossing the Valley of Death,” in P. Belliveau, A. Griffin, and S. Somermeyer (eds.), The PDMA Toolbook for New Product Development (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2002), p. 119.

As seen in Figure 7-6, the valley of death seems to originate somewhere near the fuzzy front end. The fuzzy front end is

the messy “getting started” period of product development, which comes before the formal and well-structured product development process, when the product concept is still very fuzzy. It generally consists of the first three tasks (strategic planning, concept generation, and, especially, pretechnical evaluation) of the product development process. These activities are often chaotic, unpredictable, and unstructured. In comparison, the new product development process is typically structured and formal, with a prescribed set of activities, questions to be answered, and decisions to be made.5

Project champions are usually neither project managers nor project sponsors. The role of the champion is to sell the idea or concept until it finally becomes a project. The champion may not even understand project management and may not have the necessary skills to manage a project. Champions may reside much higher up in the organizational hierarchy than the project manager.

Allowing the project champion to function as the project sponsor can be as bad as allowing them to function as the project manager. When the project champion and the project sponsor are the same person, projects never get canceled. There is a tendency to prolong the pain of continuing on with a project that should have been canceled.

Some projects, especially very long-term projects where the champion is actively involved, often mandate the existence of a collective belief. The collective belief is a fervent, and perhaps blind, desire to achieve that can permeate the entire team, the project sponsor, and even the most senior levels of management. The collective belief can make a rational organization act in an irrational manner. This is particularly true if the project sponsor spearheads the collective belief.

When a collective belief exists, people are selected based on their support for that belief. Champions may prevent talented employees from working on the project unless they possess the same fervent belief as the champion does. Nonbelievers are pressured into supporting the collective belief, and team members are not allowed to challenge the results. As the collective belief grows, both advocates and nonbelievers are trampled. The pressure of the collective belief can outweigh the reality of the results.

There are several characteristics of the collective belief, which is why some large, high-technology projects are often difficult to kill:

- Inability or refusing to recognize failure

- Refusing to see the warning signs

- Seeing only what you want to see

- Fearful of exposing mistakes

- Viewing bad news as a personal failure

- Viewing failure as a sign of weakness

- Viewing failure as damage to your career

- Viewing failure as damage to your reputation

Project sponsors and project champions do everything possible to make their project successful. But what if the project champion and the project team and sponsor have blind faith in the success of the project? What happens if the strongly held convictions and the collective belief disregard the early warning signs of imminent danger? What happens if the collective belief drowns out dissent?

In such cases, an exit champion must be assigned. Sometimes the exit champion needs to have some direct involvement in the project in order to have credibility, but direct involvement is not always a necessity. Exit champions must be willing to put their reputations on the line and possibly face the likelihood of being cast out from the project team. According to Isabelle Royer:

Sometimes it takes an individual, rather than growing evidence, to shake the collective belief of a project team. If the problem with unbridled enthusiasm starts as an unintended consequence of the legitimate work of a project champion, then what may be needed is a countervailing force—an exit champion. These people are more than devil’s advocates. Instead of simply raising questions about a project, they seek objective evidence showing that problems in fact exist. This allows them to challenge—or, given the ambiguity of existing data, conceivably even to confirm—the viability of a project. They then take action based on the data.6

The larger the project and the greater the financial risk to the firm, the higher up the exit champion should reside. If the project champion just happens to be the chief executive officer, then someone on the board of directors or even the entire board of directors should assume the role of the exit champion. Unfortunately, there are situations where the collective belief permeates the entire board of directors. In this case, the collective belief can force board members to shirk their responsibility for oversight.

Large projects incur large cost overruns and schedule slippages. Making the decision to cancel such a project, once it has started, is very difficult, according to David Davis:

The difficulty of abandoning a project after several million dollars have been committed to it tends to prevent objective review and recosting. For this reason, ideally an independent management team—one not involved in the projects development—should do the recosting and, if possible, the entire review…. If the numbers do not holdup in the review and recosting, the company should abandon the project. The number of bad projects that make it to the operational stage serves as proof that their supporters often balk at this decision.

. . . Senior managers need to create an environment that rewards honesty and courage and provides for more decision making on the part of project managers. Companies must have an atmosphere that encourages projects to succeed, but executives must allow them to fail.7

The longer the project, the greater the necessity for exit champions and project sponsors to make sure that the business plan has “exit ramps” such that the project can be terminated before massive resources are committed and consumed. Unfortunately, when a collective belief exists, exit ramps are purposefully omitted from the project and business plans. Another reason for having exit champions is so that the project closure process can occur as quickly as possible. As projects approach their completion, team members often are worried about their next assignment and try to stretch out the existing project until they are ready to leave. In this case, the role of the exit champion is to accelerate the closure process without impacting the integrity of the project.

Some organizations use members of a portfolio review board to function as exit champions. Portfolio review boards have the final say in project selection. They also have the final say as to whether or not a project should be terminated. Usually one member of the board functions as the exit champion and makes the final presentation to the remainder of the board.