1 PROJECTS AND PROJECT WORK

LEARNING OUTCOMES

When you have completed this chapter you should be able to demonstrate an understanding of the following:

- the definition of a project;

- the purpose of project planning and control;

- the typical activities in a system development life cycle;

- system and project life cycles;

- variations on the conventional project life cycle;

- implementation strategies;

- the purpose and content of the business case;

- types of planning documents;

- post-implementation reviews.

1.1 PROJECTS

A project may be defined as a group of related activities carried out to achieve a specific objective. Examples of projects include building a bridge, making a film and re-organising a company. We will be focusing on projects that implement new information technology (IT) applications within organisations. These are technical but also involve changing the organisation in some way.

Before a project starts, one or more people will have an idea about a desirable product or change. Before this idea can become the subject of a project, a business case will need to be made showing that the value of the benefits of completing the project will be greater than the costs of implementing and operating the new (or revised) system that the project would create. This will not only need to consider business concerns, but also the technical difficulties of the project. This is underlined by the alternative name of feasibility study for the business case.

![]()

COMPLEMENTARY READING

Exploiting IT for Business Benefit, Bob Hughes, BCS

If the proposal is accepted by the organisation, the project that emerges should have the following attributes:

- A defined start point, which is when:

- the exploration of the idea is converted into an organised undertaking;

- the idea obtains business backing and a project sponsor – an individual or group within the organisation who will take ownership of the project and ensure that it has the appropriate financial resources;

- a commitment is made to provide the necessary resources;

- responsibilities are defined;

- initial plans are produced.

- A set of objectives, which:

- drive the actions of the project team towards achieving a common goal;

- should be stated and understood at the start of the project;

- should be clear and unambiguous.

- A set of outputs or deliverables, which allow the objectives to be satisfied.

- A date by which the objectives should be met and a budget setting the maximum allowable cost of the project.

- A unique purpose – routine activities are not projects.

- Benefits for the organisation which justify carrying out the project, and which are:

- ideally, measurable;

- greater than the costs.

In some cases, the cost of the project might be greater than the immediate benefits, but completion of the project may enable other projects to be implemented which will reap the benefits – this is often the case with IT infrastructure projects.

1.2 SUCCESSFUL PROJECTS

To be successful, a project should:

- enable the stated objectives to be achieved;

- be delivered on time and within budget;

- deliver a system that performs to agreed specifications, including those relating to quality;

- satisfy the project sponsor and other interested parties. The term stakeholder refers to anyone who has an interest in the project: their role is discussed further in Section 8.3.

These are project objectives. The IT functions that are delivered, including both hardware and software, should enable the organisation to meet its business objectives. For example, the development of a new website could enable an organisation to sell its products online to a wider market. However, while the project objective of delivering the new website might be achieved, the business objective of selling more products might be denied because of external factors such as a general downturn in the market.

Objectives are often called success criteria. If they are satisfied then the project can be deemed a success. They should focus on the desired state of affairs that should exist when the project is completed, rather than on the details of how the project is to be done.

There is a mnemonic to help recall the characteristics of good success criteria. They should be SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Resource-constrained and Time-constrained). The success criteria should be specific and measurable – for example, ‘increasing market share’ is too vague: this could be the outcome of lots of different activities and the amount of increase expected is not defined. ‘Creating an online booking system that will be used by at least 30 per cent of customers in its first year’ is more specific. As well as being specific and measurable, success criteria must be clearly achievable. If it is clear that they are not, people are likely to ignore them. Finally, part of the statement of objectives will always define a deadline and an overall target cost.

In summary, this means developing the project at a specified cost, within a specified time, to meet a specified business requirement. These three specifications are closely linked and any change to one will affect the others. The project objectives which relate to cost, time and the degree to which requirements are satisfied (‘scope’) are often called the ‘iron triangle’.

The sponsor and users typically want a system with a broad scope – capable of a multitude of functions – to be delivered immediately and at low cost. As a general rule, not all of this can be delivered, and so the agreed project objectives will be a compromise between the three corners of the iron triangle of cost, time and scope.

If the scope of requirements strays outside this area of compromise, it will increase cost or delivery time and the project could cease to be viable. The costs of the project could as a result exceed the value of the benefits of the project. Generally an increase or decrease in any of the three factors of the triangle will affect the others. Thus if the deadline for project completion has to be brought forward, either the scope would have to be reduced or more staff could be employed to work in parallel on the project, which would increase costs – and some project risks. There may be exceptional circumstances in which a project can, with the sponsor’s agreement, fail to meet one or more of these success criteria and yet still be considered a success, usually because the business objectives can still be met.

While this book-keeping element of successful project management is important, note that the perceived value of the benefits of a project may be quite subjective. The final judges of the success or failure of a project will be the project sponsor and the users of the delivered IT applications. Being sensitive to their needs will be as important as sticking to the letter of a contract.

CANAL DREAMS BOOKING SYSTEM PROJECT SCENARIO

Canal Dreams is a major holiday company that specialises in canal holidays. The present organisation is the result of the acquisition of six regional canal boat leasing operators, as Canal Dreams has expanded over a number of years. Currently there is a central call centre that deals with holiday bookings using an in-house computer-based booking application, which is now some years old.

Business development analysts have identified the need for an enhancement of the system so that customers can book boating holidays directly over the internet. One advantage of this is a possible increase in bookings by overseas customers.

The current IT system was developed by an external software development company some time ago, and currently there are two software developers who maintain the current system and implement relatively minor enhancements. However, the management of Canal Dreams does not believe that it has sufficient in-house resources to develop the new functionality, particularly as they see the required extension to the system as an urgent business need. The intention is therefore to contract out the system design and building of the system to an external company.

This Canal Dreams project scenario will provide examples throughout the text. The main objective in this scenario is the enhancement of the Canal Dreams holiday booking system to allow potential customers to book holidays over the web. This will have business benefits for Canal Dreams. With the new system, potential customers can browse an online brochure of boats and start and finish locations, check if there is one available where and when they wish to go on holiday and, if available, make the booking – all via the internet. The new system will thus make booking possible 24 hours a day and seven days a week, and this improved accessibility, it is hoped, will increase sales. An automated online system should eventually allow staff reductions as the internet becomes the preferred medium for bookings.

In order to meet these business objectives, the proposed system will need certain functionalities. For instance, it should allow the potential customer to check the availability of a boat at a particular boatyard in a particular week. These functional requirements will include not just those of the organisation but also legal requirements, such as those relating to distance selling.

![]()

COMPLEMENTARY READING

A Manager’s Guide to IT Law, Jeremy Holt and Jeremy Newton, BCS

There will also be quality requirements: for example, the time it takes the computer to respond to a user query on boat availability needs to be quick so that frustrated potential customers do not abandon their queries and try a competitor’s website.

If the system were to exceed the cost requirement, the potential additional income through extra bookings and staff savings might not be enough to meet the cost of implementing the system. Canal holidays are a seasonal business and so implementation of system enhancement will need to be at a quiet time of the year before the bookings for the next season start to come in. This implies a certain deadline for system implementation.

1.3 PROJECT MANAGEMENT

Having established and agreed objectives, how do we then achieve them? The first step is good planning. Having produced good plans, monitoring and effective control of the project is needed to fulfil the plans and achieve the agreed objectives. Someone has to take responsibility for controlling the work in accordance with the plans. This is the role of the project manager.

A successful project cannot be guaranteed, but certain things will contribute to success, such as:

- Clearly defined responsibilities: it is essential that project roles and responsibilities be clearly defined, documented and agreed.

- Clear objectives and scope: any manager who embarks upon a project without clearly establishing the scope of the expected deliverables, together with cost, time and quality objectives, is creating problems for the future. These should be laid down in terms of reference or some other document that defines the scope of the project objectives.

- Control: despite their individual differences, all projects can be controlled. It is important to establish at the outset how best to control the work and how to exercise that control.

- Change procedures: ideally the project manager would like to work in a world where there is no change or uncertainty. Unfortunately it has to be recognised that there is uncertainty and that change will happen. Appropriate change procedures are needed to deal with it.

- Reporting and communication: clear reporting of project progress and any problems allows action to be taken quickly to resolve problems. Effective communication with all stakeholders can help avoid conflicts.

A project management method is a set of processes used to run a project in a controlled and, therefore, predictable fashion. The design and development procedures by which the objectives of the project are satisfied – for example, the use of object-oriented analysis – constitute the development methods.

There are various project management methods which complement the development methods that can be used – a well-known one in the UK is PRINCE2. In general, project management methods are applicable to a range of project types, whereas development methods tend to be specific to projects with particular types of deliverables or objectives. This is because the development tasks will vary according to the objectives of the project. Organising an office move, developing a software application and providing disaster recovery facilities are all projects in their own right. Each has a different method of development but all are controllable using the same project management processes. Following a method does not guarantee that a project will be successful. If applied carefully, however, it will provide management with the means to be successful.

ACTIVITY 1.1

Assume that you are a manager of an office department that is going to be relocated to a building five miles away. Day-to-day management of the move will be delegated to one of your staff. What would be the main sequence of activities needed to plan and carry out the move? You want to leave as much of the detailed work as possible to your subordinates, but at which key points would you need to be involved to check progress?

Solution pointers for the activities can be found at the end of the chapter.

1.4 SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT LIFE CYCLE

Dividing a development method into a number of processes is a widely accepted practice. This allows systems to be designed and implemented using a methodical and logical approach. The number and names of these processes will vary from organisation to organisation. In some cases, stages will be combined or split. Generally speaking, the following processes belong to the system development life cycle (SDLC) that applies to IT projects:

- initiation;

- identification of the business case;

- project set-up;

- requirements elicitation and analysis;

- design;

- construction;

- acceptance testing;

- implementation/installation;

- review and maintenance.

This suggests a particular sequence of processes. However, different parts of an application under development could be at different stages. For example, one component could be still being designed while another is being coded. The key point is that all these technical processes have to be dealt with somewhere within the project.

Each process creates one or more tangible products or deliverables. Delivery of the products of each process can act as a milestone at which we can judge the progress and continuing viability of the project.

One variation of this model is where software and/or hardware components are to be acquired off the shelf. Because the components already exist, the design and construction processes are not carried out. Instead, a selection process is devised consisting of methods of evaluating the suitability of candidate products. The products to be used are then selected. Some element of customisation may be needed to modify the product for use in the organisation. An acceptance test could be carried out.

![]()

ADVANCED TOPIC Build versus buy

The question of whether in fact new software has to be written must always be asked. Existing software bought off the shelf has the following advantages:

- It already exists, so it can be installed more quickly.

- It can be seen in action, so users can get a good idea of its quality.

- Existing users will have effectively tested it by reporting any defects, which will then have been removed by the supplier, so the software is likely to be more reliable.

- As there are many different organisations using the software, development costs will be shared and the cost of the software should be cheaper than if you had built it yourself.

- You do not have to employ software developers to build the new system, who may then become surplus to requirements.

- The vendor should supply updates to deal with statutory changes so maintenance of the installed system will not be a responsibility of the host organisation.

However, there are disadvantages in buying off-the-shelf software, which may encourage the building of new software:

- Off-the-shelf software may not meet all the particular requirements of the host organisation.

- The organisation may have to change its business processes to fit in with the way in which the off-the-shelf application works.

- If you adopt an off-the-shelf application, you can be as good as your competitors – who may have the same system – but you cannot be better than them.

- Once you have adopted a particular off-the-shelf package, it may be difficult to change. Off-the-shelf software is often leased on an annual licence and if the vendor increases the licence fee, you may be trapped into having to pay it.

- If the vendor ceases to trade, this may put you in a difficult situation if changes to software are needed.

1.4.1 Initiation

The first two processes – initiation and the identification of the business case – are, strictly speaking, not part of the project. Their purpose is to establish the justification for the project: an outcome could be a decision not to go ahead with the project, which means the planning of the project only starts in earnest after these two processes have been completed.

The objective of project initiation is to decide the most appropriate way to respond to a request for some work to be done, taking into account any business or technical strategies that the host organisation might have.

It begins with recognition by an organisation’s managers that it has a need that can only be satisfied by some form of project. The need might be a perceived problem to be solved, a request for something new to add to an existing system or the identification of some new way of delivering value to the organisation. The initiation process checks that a problem or opportunity really exists and decides whether the proposed change appears to be desirable, and whether a project is the best way to implement the change. This phase is typically short. The end result is a decision by the project sponsor on whether resources should be spent on further investigation of the feasibility of the proposal, including the business case for it. Terms of reference should be drawn up, outlining the scope of the proposal to be investigated and authorising staff to carry out the investigation. Staff carrying out the investigation need to have permission to gather information from those working in the areas affected, along with other stakeholders.

1.4.2 Identification of the business case

The business case or feasibility study assesses whether the proposed development is practical in terms of the balance of costs and benefits, the technical requirements and the organisation’s information system objectives. The deliverable is a feasibility report which, among other things, presents the business with a range of options aimed at providing a solution.

Apart from the question of business viability – the benefits being greater than the costs – factors influencing the decision about the appropriate option include:

- Budget constraints: the benefits may be greater than the estimated costs, but does the organisation have the resources to pay for the investment?

- Technical constraints: can the proposed project be completed with the technology currently available?

- Time constraints: can the proposed project be completed in the available time?

- Organisational constraints: can the organisation cope with the changes that the new development will demand?

One or more of these constraints may prevent a project from being developed any further. The content of the business case is discussed in more detail in Section 1.9.

1.4.3 Project set-up

Based on the recommendation of the business case report, the organisation will decide whether to go ahead with the full project. At this point a group variously called the steering committee, project board or project management board is set up to oversee the project in the organisation’s interests. A project manager needs to be appointed and an initial project team set up to start work.

More detailed planning for the project takes place. Important decisions will be taken about how the declared project objectives are to be fulfilled. Terms of reference for the project to implement the new system, as opposed to simply investigating its feasibility, are drawn up.

1.4.4 Requirements elicitation and analysis

This phase defines the requirements of the new system in detail and identifies each business transaction. Some work on identifying requirements will already have been done when the business case was being identified. The elicitation or gathering of requirements could involve:

- interviewing users and their managers;

- examining documentation describing the current operations;

- analysing operational records created by the current system;

- observation of work practices;

- joint application development (JAD) sessions – where groups of stakeholders and business analysts meet in intensive (usually day-long) sessions to identify and agree detailed requirements;

- questionnaire surveys.

In some cases, mock-ups or prototypes of parts of the new system could be used to help the users clarify their ideas about the requirements.

ACTIVITY 1.2

What kinds of people should the business analyst interview in the Canal Dreams ebooking enhancement project in order to obtain the requirements for the new system?

Business analysis techniques such as business process modelling or data analysis will usually be applied to organise the raw data collected.

![]()

COMPLEMENTARY READING

Business Analysis 2nd Edition, edited by Debra Paul, Don Yeates and James Cadle, BCS

At the end of this phase, some form of requirements statement is produced. This describes what the final system should be able to accomplish and lists all the major features of the end product. It forms the basis of the contract between the customer for the new system and the developers.

At this point an outline of the test cases, consisting of test transactions and the results expected from them should be drafted. As will be seen, these will be used to check that the delivered system conforms to the requirements statement when acceptance testing is done.

1.4.5 Design

If it is decided to build a new system, rather than buying a ready-made or off-the-shelf application, then a design phase is needed. This activity translates the business specification for the automated parts of the system into a design specification of the computer processes and data stores that will be needed.

Where a new application is to be built, the elements to be designed include:

- inputs;

- outputs;

- processing;

- data and information structures.

The identification of the inputs, outputs, business rules and information that the system will process is known as logical design. The physical design is concerned with the actual appearance of the input and output screens and the printed reports that will be produced by the implemented system. Several different physical designs could satisfy the same underlying logical design. Physical design in this phase is essentially concerned with the system as it will appear to the outside world. Further internal physical design of the software and data structures will take place in the next phase.

Where an off-the-shelf application is to be used, because it already exists, its design will already have been carried out. In this case, the issue is finding the package whose features most closely match the business requirements. The process by which available packages are to be evaluated, and those which represent good value selected, must be planned. Evaluation may involve trying out demonstration versions of the software, site visits to existing users of the software, and careful study of the suppliers’ documentation. In some cases the existing software will need to be customised – that is, modified – to meet the organisation’s particular needs.

ACTIVITY 1.3

List some of the screens and other possible inputs and outputs that the new Canal Dreams ebooking enhancement might need and which might need to be designed.

1.4.6 Construction

This process has the objective of designing, coding and testing software and ensuring effective integration between different software components. For example, the new Canal Dreams holiday ebooking enhancement would need the development of a application to record holiday bookings made by customers online. It is very rare these days for new IT applications not to be linked in some way with existing applications. In the case of the Canal Dreams ebooking enhancement, an existing database of holiday bookings used by telesales staff can be accessed and updated, and much existing functionality can be used. It is therefore likely that as well as new code being developed, some existing code may need to be amended to deal with the enhancement.

Procedure manuals will also be produced and new hardware may have to be acquired. In the case of Canal Dreams, additional servers will be needed to deal with the increase in internet transactions. During this phase, the requirements statement will be re-examined to ensure that it is being followed to the letter. Normally any deviations have to be approved through a formal change procedure (see Chapter 4).

1.4.7 Acceptance testing

In Section 1.4.4, we suggested that test cases to ensure that the requirements had been met should be outlined at the requirements analysis stage. These can now be used to check the delivered system. This testing could be carried out by knowledgeable representatives of the users and IT support staff before its implementation as an operational system. It is inevitable that during this stage, the user will uncover problems that the developer has been unable to detect.

In the case of the Canal Dreams ebooking enhancement, a problem is that users of the new facility will be members of the public who we do not currently know. Usability tests using external members of the public recruited for this purpose will be needed to test the customer-facing interfaces.

These acceptance-testing activities may overlap with implementation. For example, some tests need to be carried out on the system when it is actually installed on the equipment that will be used operationally.

1.4.8 Implementation/installation

Here the project reaches fruition. Hardware that has been purchased is delivered and installed. Software is installed, users trained, and the initial content of databases set up. In the case of the Canal Dreams ebooking enhancement, the general public will need to be informed of the new facility for online booking. There are various strategies for implementation; these are discussed later in Section 1.10.

1.4.9 Project closure

Although we have put this after implementation/installation, a project could have been abandoned at an earlier stage because its business case was no longer valid.

In the case of successful project completion, certain tasks will need to be done on closure, including:

- sign-off of acceptance documents by the project sponsor – this may be conditional on other key stakeholders giving approval first;

- handing over responsibility for maintenance and support to a permanent team;

- closing down accounts relating to the project;

- the project manager writing a lessons learnt report;

- releasing and re-allocating project resources, including the project team and the project manager;

- arranging publicity to tell the outside world about the project’s success.

1.4.10 Review and maintenance

At an agreed interval after the system has been made operational, a post-implementation review should be carried out by a business analyst who was not involved in the original project. The review checks that the operational system has actually delivered the benefits envisaged in the original feasibility report. Changes may sometimes result from this review if the system does not completely fulfil its original requirements, but they may also be the result of users identifying new requirements. Changes may also come about because of changes to government regulations or alterations in the way the organisation does business. These changes can be made as part of maintenance work, or they can become projects in their own right.

1.5 PROJECT MANAGEMENT AND THE DEVELOPMENT LIFE CYCLE

The processes described above represent groups of development activities which have to be performed to complete the project. There is also a need for management reviews at which the progress and direction of the project can be formally assessed.

Most projects contain elements of uncertainty which make it difficult to meet exactly all planned targets. This uncertainty tends to be greatest at the beginning of the project, when little may be known about detailed requirements or any novel technologies to be deployed, but gradually decreases as the project progresses. This makes it difficult, at the beginning of the project, to plan its later phases in detail. For example, it would be difficult for Canal Dreams to plan in detail the software code to be developed without a detailed understanding of the new requirements and how they will affect the current system.

For the purposes of control there is a need to break the project into manageable units of work. These are variously called stages or phases. This is similar to dividing development into processes, except that it focuses on how best to manage the project. No two projects will be broken down identically because no single project structure can provide the best management control for all projects. In some cases – perhaps in smaller projects – two activities of the system development life cycle, such as design and construction, might be treated as one stage for management purposes. On larger projects a single activity of the development life cycle might be split into several management stages. For example, the construction phase might be broken into different management stages dealing with the construction of different parts of the system.

The end of each stage is marked by a formal review, involving the project sponsor, which assesses the work done and the work still to be done on the project as a whole, and whether the business case is still valid. The review concludes with a formal sign-off of the last stage and the project sponsor’s approval to continue to the next stage of the project.

1.6 ELEMENTS OF PROJECT MANAGEMENT

The motivation behind consolidating or splitting up development processes is to ensure controllability of work. In addition, the project manager has to tailor project management procedures to maintain control over the project, while avoiding excessive management bureaucracy. Although the overall project management process remains the same, different projects require different levels of control. The amount of effort required for project management, for example, needs to be appropriate to the size of the project. However, the fact that a project is small does not mean it requires no control.

The processes that need to be tailored relate to the following:

- planning and estimating;

- monitoring and control;

- issue management;

- change control;

- risk management;

- project assurance;

- project organisation;

- business change management.

All of these will be described in greater detail in later sections of this book, but a brief overview will be useful at this point.

1.6.1 Planning and estimating

Good planning increases confidence within the project team. Without a plan there is no means of knowing whether dates can be achieved, nor whether the project is adequately resourced.

The aim is to detail all the activities, the sequence in which they are carried out and the resources they need. The plan shows when activities are to be performed and helps to estimate the staff effort needed and the most likely finish dates. An outline plan for the whole project will be made initially, then a detailed plan for each stage will be created nearer the time at which that stage is to start. Chapter 2 looks at planning in more detail.

1.6.2 Monitoring and control

The project plans form the basis for monitoring progress against the expected achievements. Tracking and control aim to ensure that the project meets its commitments in terms of deliverables, quality, time and cost by tracking the current state of the project against the plan and identifying any need to re-plan. Chapter 3 examines project control in more detail.

1.6.3 Issue management

During the course of a project, problems will be identified which are considered likely to affect the project’s success. These problems or project issues may or may not be within the control of the project manager, but do not include authorised changes to the project requirements – these have their own special procedures (see Section 1.6.4). The project manager should ensure that a system is in place for recording these issues, monitoring their status and starting any actions needed.

1.6.4 Change control

Any project will be subject to change. A change may result from a modification to requirements or may come as a result of errors found in testing. Any requests for change should be made through a formal change management process. Failure to incorporate necessary changes reduces the benefit obtained from the project. However, accepting changes in an uncontrolled manner can cause problems related to the cost, time scales and overall business case for the project.

Chapter 4 examines change control and configuration management.

1.6.5 Risk management

All projects are subject to risk. If these risks are not managed, they can have a detrimental effect. A suitable risk management process assesses and manages project risks.

Risks are different from issues. A risk is an unplanned occurrence which could happen, but has not yet done so. An issue is an unplanned occurrence which has already happened and which requires the project manager to request or initiate action not previously planned.

Risk management identifies and quantifies risks before they happen, and plans and implements actions to eliminate risks or reduce their probability or impact. Risk management ensures that projects are only undertaken with a full understanding of the potential implications of the risks involved. Chapter 7 deals with risk in more detail.

1.6.6 Project assurance

As noted above, project monitoring and control involves assessing various aspects of work, including progress, cost, changes, issues, risk and quality. When pressure mounts on a project to meet its deadline, it is tempting to ignore some of the checks and balances imposed by project control and to focus exclusively on the work to be done. This lack of control can be dangerous and can lead to project failure. Project assurance is a set of procedures which ensures correct project control is maintained. This involves auditing by staff outside the project team.

1.6.7 Project organisation

A key factor in any project is effective project organisation, wherein the roles and responsibilities of all participants are clearly defined and understood. Chapter 8 explicitly addresses this topic.

1.6.8 Maintaining stakeholder engagement

Winning stakeholders’ support for a project is important for project success. Unless time has been spent communicating with stakeholders and making sure that users know exactly what to expect of the new system, the project could meet its formal requirements but still be seen as a failure by its users.

1.7 DEVELOPMENT PROCESS MODELS

It was noted in Section 1.4 that organisations involved in IT development need a well-defined, repeatable and predictable system development life cycle. Projects creating different types of products need different development life cycles. Whatever the life cycle, it will be a set of activities which, after completion, results in one or more products that are delivered to a customer. Each activity in the process will have a defined input and output.

Effective development methods have certain characteristics. They are made up of an overall set of techniques and activities from which team members working on a new project of a particular type can select the most appropriate subset. The method should never require a task that does not produce something useful to the project.

The conventional system development life cycle for IT projects was described in Section 1.4. This has certain general characteristics that could apply to a number of different life cycles. However, it assumes that technical processes will vary according to the type of project. For example, it distinguishes as different project types (with differences in the types of processes carried out) those in which software is to be developed and those in which existing software is to be obtained off the shelf. In Section 1.5, however, it was noted that to make projects more manageable, the processes could be split up or sequenced in different ways. Here we look at some of the options for this.

1.7.1 Waterfall model

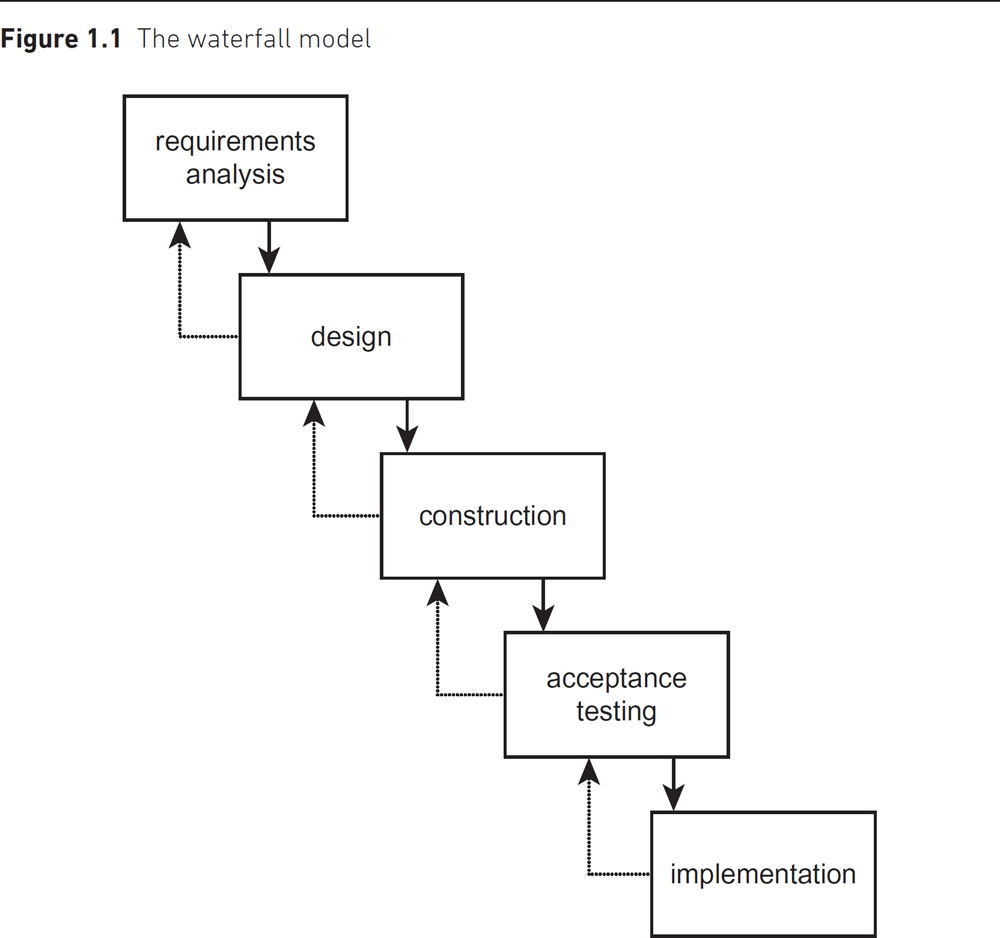

The waterfall model (see Figure 1.1) is the basic phased model of a development cycle. It is also known as the one-shot or once-through approach. The model takes its name from the way each phase cascades into the next. It is assumed that activities are normally done in a strict sequence, although there is some scope for re-working stages once they have been completed. Phases should produce a sequence of deliverables, such as the requirements statement, design documents and software structures, where the output from each phase is an input to the next.

This approach provides for feedback loops which are activated when there is a need to revisit an earlier stage to redesign, recode and so forth. It is possible to return to any previous phase, although this could well require extensive replanning. The ideal is for quality control activities to be associated with each phase, so that once the deliverables of a stage have been signed off they should not need to be reworked.

This model is probably best used on projects where requirements have been clearly defined and agreed. Unfortunately, most projects do not have clear requirements at the beginning. As the model relies upon having each phase completed and signed off, it can become bureaucratic and time-consuming. It works best where there are few changes to requirements during the development cycle.

Another drawback is the amount of project documentation which can be created. The distinct testing phase at the end of the project means major defects could be undetected until late in the project, when they are more difficult to repair. It is also easy to misjudge progress: just because the requirements have been signed off, it does not necessarily mean the requirements have been clearly understood.

1.7.2 Agile project practices

![]()

ADVANCED TOPIC Agile practices

A response to the limitations of the waterfall approach has been that some have argued for the adoption of what are called agile practices. These tend to be practices that reduce bureaucratic obstacles by encouraging intense, informal, communication between project participants. Some of these work at the level of individual work teams. Scrum, for example, breaks a project into a number of increments (see Section 1.7.3) of about two-week duration called sprints. Within sprints, Scrum breaks individual activities into a series of small steps which are listed in a backlog. Each day the project team members report on their progress in implementing the items in the backlog in short ‘stand-up’ meetings. Other agile approaches – such as Extreme Programming (XP) – focus on software development practices. XP, for example, calls for software developers to work together in pairs, so the coding decisions of one developer are always checked by the other as the code is entered at a work station. Another XP practice is the integrating of all existing software components on a daily basis to ensure consistency.

From the point of view of those who manage projects, a common theme of the different agile approaches is the adoption – to differing degrees – of the principles that support the incremental and iterative models described in the next two sections, and which actually predate the first use of the description ‘agile’ (and are part of the BCS Foundation Certificate syllabus). The Dynamic Systems Development Method/Atern Method (DSDM Atern) is the approach that most closely reflects the principles described in the next two sections.

We will be returning to other relevant agile practices in later chapters, particularly Chapter 5, which discusses quality issues.

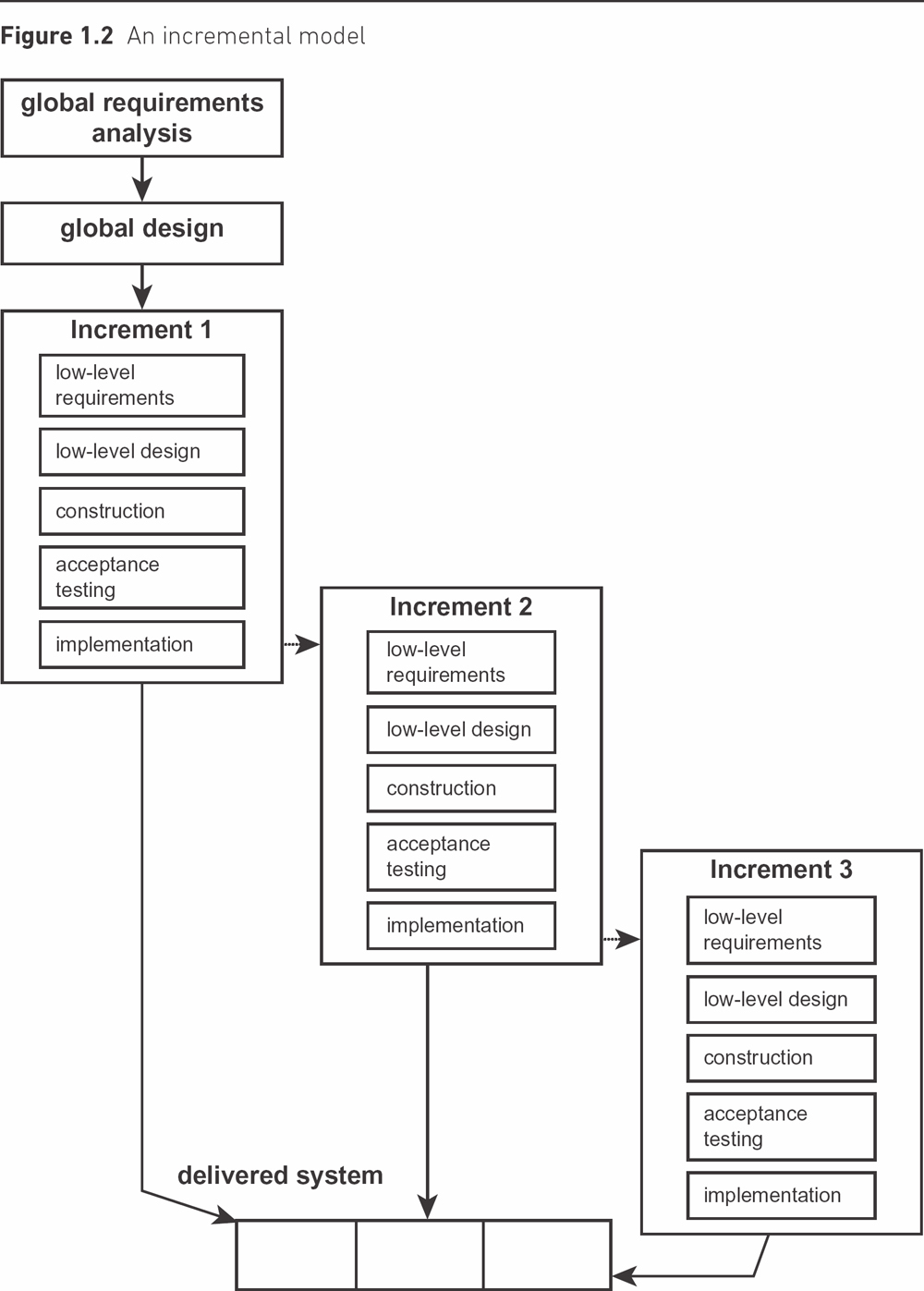

1.7.3 Incremental model

Although the incremental model (see Figure 1.2) is similar to the waterfall model, it involves the development and delivery of functionality in fragments or increments. Typically, global requirements are defined and an overall architecture designed. Then the product is developed in increments. After each increment is designed, developed and tested, it is system tested and then becomes operational, so that users get their new system in instalments. This approach works best when the requirements are relatively well-known. It can work well with larger projects, as these are effectively broken into a series of mini-projects, each delivering an increment.

The incremental model is often used in conjunction with timeboxes. The deadline for completion of the increment is fixed and the features to be delivered by the increment are ranked according to importance. The least important features may be dropped to ensure that the deadline is met. The dropped features can be implemented in a subsequent increment if they are still required.

1.7.4 Iterative model

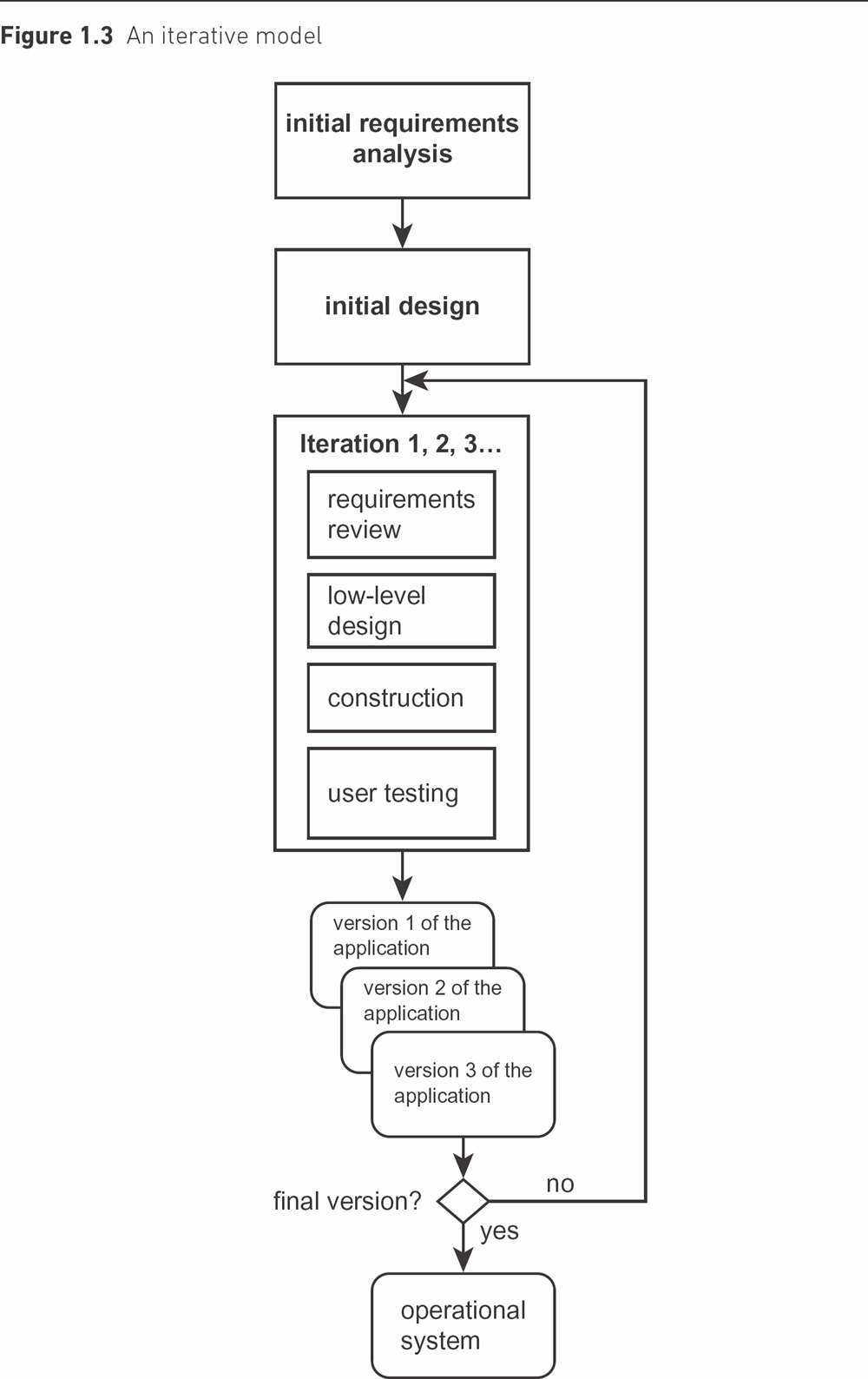

This model (see Figure 1.3) is suited to situations in which the requirements are not clearly understood and where there is a need to begin development quickly to create a version of the product which will demonstrate its look and feel. Early versions, or prototypes, of the system are created to help the customer identify and refine requirements and design features. The customer can make suggestions for possible changes to be incorporated into a further version of the software which is then evaluated.

A risk associated with this model is not knowing when to stop iterating. The iterative approach is potentially difficult to monitor and control.

The incremental and iterative models work well together. An application can be broken down into a number of increments, each of which can be implemented through a series of iterations.

1.8 THE PROJECT PLAN

During the project set-up phase (see Section 1.4.3), a project plan is produced that consists of several different types of documents, including activity networks and Gantt charts (see Chapter 2).

The project plan is a set of documents that co-ordinates all the various project processes, bringing together all the planning documents used to manage and control the project. It is not cast in stone and will be amended as necessary during the lifetime of the project. The plan defines the project’s scope, schedule and cost, as well as the supporting processes related to risk, procurement, human resources, communication and quality.

1.8.1 Project initiation document

A good starting point is the preparation of a project initiation document (PID) or project management plan. Different project management methods give this document different names, but in essence it serves as an agreement between the sponsors and the developers of the project. It has the following key elements.

- An introduction, which describes:

- the project background;

- the document’s purpose;

- the business justification for the project, including a brief summary of costs and benefits (see Section 1.9).

- Project goals, objectives and deliverables.

- A project organisation chart which names:

- the project sponsor(s);

- the project manager;

- any sub-project or stage managers;

- the lead user representative(s);

- the lead supplier representative(s), if appropriate.

The organisation chart should detail the reporting relationships of all members of the project team and identify any steering committee (or project board or project management board) established for the project. It should show the reporting relationship between the steering committee and the project team. It should also specify the levels up to which named individuals, groups (such as the steering committee) or roles can authorise:

- the commitment of resources;

- the sign-off for documentation and other project products;

- changes to goals, objectives, deliverables cost or time scale.

Chapter 8 discusses many of the issues involved in project organisation.

- A project structure section that describes how the project will be broken down into manageable portions of work which will be administered as stages.

- A list of project milestones, i.e. significant events in the project for which dates need to be clearly specified. Milestones are used to measure the progress of a project and can be the start or completion of a major project phase. Milestones are events that consume no resources in themselves, but enjoy a great deal of attention from management at a senior level. Additional resources may be used in reviewing the state of the project before or after the milestone has been reached.

- Project success and completion criteria.

- A management control section that covers:

- the frequency, timing, recipients and format of progress reports;

- how the plan will be produced and maintained;

- what information will be monitored and recorded;

- how the information will be recorded;

- how packages of work will be signed off and reviews conducted;

- the people responsible for recording and assessing the impact of any changes;

- the people responsible for authorising different levels of change to goals, objectives, deliverables, cost or completion date.

Chapter 3 is devoted to monitoring and control.

- A risks and assumptions section that should identify any high-level risks to the project and propose specific actions to reduce or eliminate each risk. It is useful to include in this section a list of assumptions made in producing the report. See Chapter 7 for more on risk and its management.

- A communication plan that provides an overview of how the project will communicate with the wider business organisation, particularly with regard to changes needed in the business in order to make the implemented IT application effective.

- A report sign-off section.

The document should be signed off by staff able to represent all areas and functions committing resources to the project and those who will be affected by the project. In so doing they implicitly accept the assumptions listed. Final sign-off should be obtained from the project sponsor. The project manager should not initiate any work which has not been explicitly or implicitly authorised in the project initiation document and signed off by the project sponsor.

1.8.2 Schedule planning

Scheduling is a key project planning technique and must take place prior to the start of work. The resources required and the consequent costs will depend on the schedule decided for the work. Effective scheduling requires:

- a definition of requirements that is agreed and unambiguous;

- a careful breakdown of work;

- the creation of a coherent and internally consistent schedule which shows when activities will start and end and the resources that they will need;

- careful monitoring of progress against the schedule.

It is the responsibility of the project manager to make sure these requirements are fulfilled. Schedules will generally be produced at several levels of detail:

- project level, at which the project steering committee or board reviews plans and progress and takes decisions;

- phase/stage level, at which project or stage managers break down the main stages of the project into activities which are then allocated to teams;

- activity level, at which team leaders allocate work to team members so that activities allocated to the team can be completed.

As will be seen in Chapter 2, the Gantt chart is an important planning document for showing the schedule.

1.8.3 Cost planning

Once the activities have been identified, the costs they incur should be assessed. The business case for a project is based on it not costing more than a specific amount. If the costs of the project exceed the value of its benefits, the project becomes uneconomic. It is also possible for an organisation to simply run out of money for a project.

Internal IT projects are usually paid for out of a user department’s budget. Where a project is being carried out for an external customer, there may be a fixed price contract. Whatever the case, it is necessary to estimate quantities and costs, set budgets and eventually control expenditure.

Effective cost planning helps:

- decision-making and control, by allowing the costs of alternative actions to be assessed;

- prompt and up-to-date collection of progress information;

- integration of expenditure projections into the project plan.

Cost planning should be done at the same levels as schedule planning; that is, at project, phase/stage and activity level (see Section 1.8.2).

Project costs may be plotted on a cumulative resource chart (see Section 3.7.2).

1.8.4 Resource planning

The project plan needs to account for various types of resources, including people, equipment and facilities. With internally resourced IT/business change projects, management must obtain resources from other parts of the company to work on a project. Functional managers responsible for various specialist departments will be key providers of resources like office space, computer equipment and specialist expertise. If you need to obtain goods or services from outside the organisation, the person responsible for contract management will be important.

A resource plan will help the project manager identify the skills needed for the project and when they are needed. For example, in many cases a project will not need a testing expert throughout its life, but only at certain times.

A useful communication tool for the project manager is the responsibility assignment matrix (RAM), a simple matrix showing individuals associated with the project on one axis and the activities for which they are responsible on the other. By plotting tasks against staff on a matrix and labelling each person’s assignments, it provides a quick and easy view of who is responsible for each task.

![]()

ADVANCED TOPIC Sources of development staff

A major IT project often requires an abnormal temporary amount of technical work that the business cannot, by itself, provide. Additional development skills might be acquired by:

Recruiting individual specialists on temporary contracts, either directly or by using agencies. Day rates for temporary staff are often greater than those for permanent staff and recruitment and training costs need to be taken into account. Depending on the type of work, temporary staff could work from their own premises, but more often they will need other facilities within the business.

In the case above, the temporary staff are employed directly by the business. An alternative approach is to have a contract with an outside specialist company where the developers used are and remain the employees of the specialist company. The specialist company is paid for the hours that their employees work.

A more radical approach is to outsource one or more project activities, such as design and construction, to an outside specialist company. The outside company will have management responsibility for delivery of a subset of the project requirements, often for a fixed price. In this case, the supplier selection and deliverable acceptance processes would still consume some of the customer’s resources.

1.8.5 Communication planning

Stakeholders, including the project team, have varying needs for communication about the project. These needs and the means by which they may be satisfied are recorded in a communication plan. The communication plan includes, among other things:

the flows of communication during the project;

how various communication tools will be used;

what meetings will be held with what attendees, and at what times.

These issues are explored further in Chapter 8.

1.8.6 Quality planning

In order to develop a system which meets all users’ functional and system performance requirements documented during analysis, a carefully considered quality plan is needed.

Quality criteria can be applied both to project deliverables and to the processes by which the deliverables are created. It is possible to check that the end products have the required qualities, and also that the processes that created them were the correct ones. Because the importance of quality often gets lost among deadline pressures and budget cuts, the project manager should emphasise it throughout the entire project life cycle, from planning to completion.

The customer must be the final judge of the product’s quality, and must therefore be involved in quality evaluation. Chapter 5 further explores the role and content of the quality plan.

1.9 THE BUSINESS CASE

This is a key document for any project. As noted in Section 1.4.1, the proposal for a project may be triggered in a variety of ways. Once a proposal has been made, senior management will decide whether to go ahead with a proposal by using a combination of qualitative and quantitative criteria, as no single method gives enough information.

Qualitative criteria include organisational fit. Does the project fit with the organisation’s strategic objectives? How does the proposed project contribute to the organisation’s future capabilities and growth? The business risks associated with a particular project should also be assessed qualitatively at this point (see Chapter 7).

A more persuasive reason for going ahead with a project, however, is often financial justification, where two of the most common quantitative financial criteria are net present value and payback period – see Sections 1.9.1 and 1.9.2 below.

The contents of the business case document would include a description of the project, its objectives and scope, a cost benefit analysis, a risk analysis, a conceptual solution, resource requirements and success criteria. Some organisations include alternative options in the business case in order to compare the recommended solution against other approaches. The business case needs to be carefully reviewed by project sponsors.

1.9.1 Net present value

The financial business case is based on the calculation of whether the value of the benefits produced by the project exceeds the money spent on developing and installing the system and eventual costs of operation. The value of costs and income, however, is influenced by when they are incurred or received. The net present value technique looks at the benefits of having money sooner rather than later. Because money in hand can be invested to make more money, the earlier you bring money into the organisation, the more it is worth.

![]()

ADVANCED TOPIC

Calculation of Net Present Value – not needed for the BCS Foundation Certificate examination

Present value calculations translate future costs and benefits to a present day value using the formula

Present Value = Future Value × (1 / (1 + i)n)

where i is the interest rate (or discount rate) and n is the number of time periods (usually in years) from today. The discount rate is the rate of interest that one could expect to receive elsewhere for an investment of comparable risk.

Say we were to receive £100 in one year’s time and the interest rate was 10 per cent (for ease of calculation!). The present value of that £100 would be

£100(1 / (1.10)1) i.e. £90.90.

In other words, if I put £90.90 into an account at 10 per cent interest then in a year I will have earned £9.09, which would give me a fraction under £100 in all.

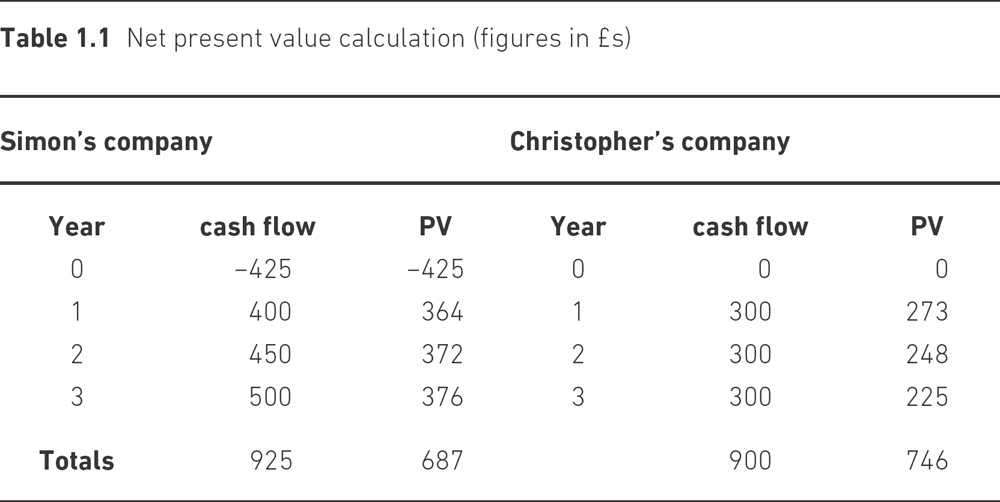

The difference between the money generated by a delivered project less the costs in a particular year is called the cash flow for that year. The net present value of a project is the sum of the net present value of each annual cash flow for the delivered project. The net present value technique allows an organisation to estimate the value of money earned several years into the future and can be used to compare the expected results of investing in different projects with leaving money in a bank at a specified rate of interest.

Here is a more detailed example, which uses a discount rate of 10 per cent. Remember that for the BCS Foundation Certificate you do not need to remember the details of the calculations.

A small organisation decides to outsource its catering to outside caterers and invites companies to tender. Whichever caterer wins the contract will pay the host organisation an agreed amount of money from the revenues that it will receive from charges for meals.

The table above represents bids from the two contractors. It can be seen that Simon’s company wants some money initially to help set up the operation. If you calculate the total cash flows for both proposals, then despite the initial subsidy paid to him, Simon’s seems slightly better, at £925 rather than £900. When the figures are converted to reflect net present value, however, Christopher’s is revealed as being much better – at £746 as opposed to £686.

![]()

COMPLEMENTARY READING

Finance for IT Decision Makers, Michael Blackstaff, BCS

1.9.2 Payback period

![]()

ADVANCED TOPIC Calculation of payback period

Net present value calculations draw attention to the fact that money received early on in the delivered system’s life cycle is more valuable than that received later. It is also true that forecasts of income become progressively less accurate as we look further into the future. Interest rates could change, or the economy could go into recession and undo our calculations. Thus how quickly you begin to make money is critical. This is what payback period calculations measure. From an organisational point of view, the shorter the payback period the better. Indeed, many organisations will be looking for a payback period of one year or less.

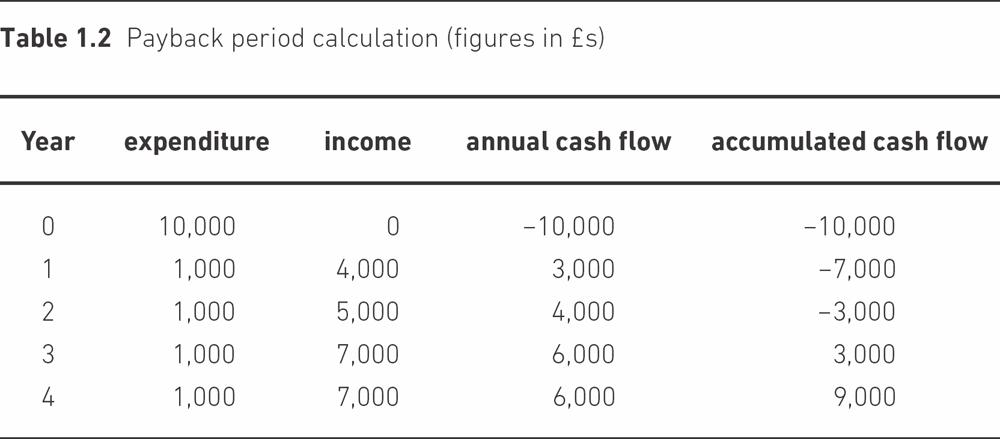

In the Canal Dreams ebooking enhancement project, say that the expenditure to set up the online booking system is £10,000. This is allocated to year 0, which really means ‘the period up to the system going live’. In the table below, the income is made up of the value of the additional bookings that the new system allows and the savings in booking staff. It can be seen the accumulated cash flow becomes positive somewhere near the middle of year 3, so the payback period is about 2.5 years.

![]()

COMPLEMENTARY READING

Finance for IT Decision Makers, Michael Blackstaff, BCS

1.10 IMPLEMENTATION STRATEGIES

At the other end of the project, there will come a time when it is necessary to convert from the old method of working to the new one brought about by the implementation of the new system. The project team, in consultation with the users, will recommend to the project board or steering committee the most suitable changeover method for the project, which may include installing IT equipment, software applications or both. The following options may be considered.

1.10.1 Direct changeover

In this case, the old system is discarded and immediately replaced by the new one. It can be considered a risky approach, but is relatively inexpensive if thorough testing has been done. The more complex and important the new system, the riskier this approach will be, especially if there is no possibility of falling back on the old system in the case of failure.

1.10.2 Parallel-running

This involves running the old and new systems together for a period of time using the same inputs and comparing the related outputs – so it serves as a continuation of the testing process. It is a safe, low-risk approach but can be expensive, particularly in terms of duplicated labour costs. An important management decision is how long to run the two systems in parallel.

1.10.3 Phased take-on

The phased approach breaks the system into components that will be introduced in sequence. It helps minimise risks but can delay the implementation of the entire integrated system. However it does present the opportunity to allow users to learn one system component at a time. It also fits neatly with incremental delivery.

1.10.4 Pilot changeover

Like the phased approach, this is a risk-reducing approach. With pilot changeover the entire new system is introduced to just one business unit or location. It can only be used if the business unit or location can use the entire system independently. Problems can be addressed and fixed before the system is introduced company-wide, but company-wide deployment of the entire system is consequently delayed.

ACTIVITY 1.4

What would be the best implementation strategy for the Canal Dreams ebooking enhancement project?

1.11 POST-IMPLEMENTATION REVIEW

The post-implementation review (PIR), or project evaluation review, is usually scheduled to take place some 6 to 12 months after the sign-off of the project. Its objective is to review the implemented system in terms of its contribution to business objectives, its usability, operating costs and reliability. It considers the following:

- whether the business and system requirements have been met;

- cost and benefit performance;

- operational performance;

- controls, auditability, security and contingency;

- ease of use.

The output from this process is a post-implementation review report. The review should be led by someone who is independent of the project and should solicit feedback from users, operations and the support team. The review should address the operational system and not the development project. The additional effort required of them might lead to users not engaging with this review. If this is the case, it is essential to explain to the users the benefits of the process – for example, that changes that could improve the system may be identified as a result.

The PIR report needs to be distinguished from a lessons learnt report. When the project has been delivered by the project team, the project manager should write a report describing the major challenges experienced during the project and how they were managed. The purpose of this report is to identify lessons that would improve the execution of future projects.

SAMPLE QUESTIONS

1. Which of the following is NOT a characteristic of a project?

(a) Ongoing nature

(b) Uniqueness

(c) Clear objectives

(d) Integration of interrelated tasks and resources

2. Which of the following is NOT managed by the project manager?

(a) Time, cost and scope

(b) The project team

(c) The project sponsor

(d) Expectations of the stakeholders

3. Which of the following tools indicates who is responsible for what?

(a) A responsibility assignment matrix

(b) A resource levelling chart

(c) An activity network chart

(d) A resource histogram

4. With which one of the following does the calculation of the payback period provide the organisation?

(a) An assessment of how quickly an implemented system will produce a profit

(b) How much future income from an implemented project will be worth in present day terms

(c) The discount rate that would give a payback with a net present value of zero

(d) The overall income that the implemented system should produce, less any initial investment

ANSWERS TO SAMPLE QUESTIONS

1. (a) 2. (c) 3. (a) 4. (a)

POINTERS FOR ACTIVITIES

ACTIVITY 1.1

Among the activities that may be considered are the following.

(i) Survey existing office requirements (for example, how many desks and chairs there are) and IT infrastructure, including servers and printers, used by the office.

(ii) Survey new office space.

(iii) Plan new office layout – who and what will go where?

(iv) Schedule the sequence of moves – it might be that not all staff should be moved at once as this will allow for some continuity of service.

(v) Select a removal company.

(vi) Organise the setting up of the infrastructure.

(vii) Pack up the old office.

(viii) Transfer to the new office, including supervision of placement of furniture etc.

(ix) Unpack in the new office.

(x) Connect telephones, etc.

As project manager you will probably want to be consulted when decisions have to be made, possibly at points (iii), (iv) and (v) as money is involved here. Useful checkpoints would be just before (vii) to check everything is in order to go ahead and after (x) to check out any outstanding problems.

ACTIVITY 1.2

There will be some interviews with fairly high-level managers, including the project sponsor (who may be the managing director, who also owns the company), to clarify the business requirements of the proposed system. Given the nature of this project. marketing specialists will need to be consulted. It is essential that this consultation take place when the business case is being prepared.

Staff who currently carry out the clerical booking operations would need to be interviewed to see how the existing system works, what data has to be held and what problems there are with the current system. Operations staff at boatyards also have to be consulted as users of the new system who need information about the bookings each week so that boats can be allocated and prepared and holiday-makers checked in. Staff in other departments need to be approached to document the interfaces between the booking operation and other parts of the overall Canal Dreams business, for example the central finance function and the maintenance staff who may need to schedule boat maintenance. In many cases, existing functionality is unaltered, but performance requirements may change. For example, the move towards online bookings may increase the number of online debit and credit payments.

Note that users include IT operational staff who would, for example, have requirements about system security as well as concerns about the move to a 24/7 service.

We usually say that end-users should be consulted, but of course, in internet transactions with the public, it is not possible beforehand to identify who these will be. In this case market research with recent telesales customers, for example, could provide insights into the needs of online customers.

ACTIVITY 1.3

Although there will be the existing functionality used by telesales, functions where potential customers have to ‘volunteer’ to use the system need more careful design than those which employees are compelled to use. It is assumed that these external transactions will be the subject of redesign to ensure their ease of use:

- Browse locations and boats,

- Check availability,

- Record boat booking,

- Cancel boat booking,

- Change allowable details, for example amend existing address, and ‘crew list’.

In order to make an internet booking, the customer must have internet access. Other communications that were previously sent by post could now be sent by email. These would include booking confirmation, final payment reminders and proof of booking and other details needed when starting the cruise.

ACTIVITY 1.4

The canal holidays business is seasonal, with very busy times of the year and times in the off-season when the business is dormant. This would seem to favour a direct changeover during a quiet period. This would allow a gradual build-up of traffic, making it easier to deal with any initial teething troubles. Note, however, that direct changeover is often avoided because of the risk that if the new system is faulty there is no alternative system to fall back on.