8 PROJECT ORGANISATION

LEARNING OUTCOMES

When you have completed this chapter, you should be able to demonstrate an understanding of the following:

- relationship between programmes and projects;

- identification of stakeholders and their concerns;

- the project sponsor;

- establishment of the project authority (e.g. project board, steering committee, etc.);

- membership of project board/steering committee;

- roles and responsibilities of the project manager, stage manager and team leader;

- desirable characteristics of a project manager;

- role of the project support office;

- the project team and matrix management;

- reporting structures and responsibilities;

- management styles and communication;

- team building and dynamics.

8.1 INTRODUCTION

This book endeavours to describe what could be called ‘best practice’ in project management. Unfortunately, not all organisations follow these good practices, which is one of the reasons why there are so many project failures. In this chapter, we describe the elements of the project management structure that should exist in an organisation that is planning and executing a project. In many cases, these roles will be known by different names to the ones we use. Many of the terms we use are loosely based on those used by PRINCE2, the project management standard sponsored by the UK government. Note that we will use capitalised initial letters, for example Senior User, where this refers to a very specific PRINCE2 concept.

8.2 PROGRAMMES AND PROJECTS

A programme is a collection or group of related projects. IT projects were often treated as individual and separate undertakings with their own distinct aims and objectives. However it became clear that grouping projects into programmes has advantages:

- Reduction of duplication – two projects may be developing a similar product.

- Co-ordination of resources – projects inevitably place demands on an organisation’s resources and it is far better to co-ordinate than compete for them.

- Management of interdependencies – if projects are dependent on one another they have to be properly co-ordinated. In such circumstances, a change in one project may introduce a delay or a consequential change in another.

- Common objectives – sometimes several different projects need to be completed for a particular business objective to be achieved.

Typically each project is assigned a project manager, while a programme is led by a programme director who ideally should be an influential member of the organisation’s senior management team and will act as a champion for the programme. The senior status needed for this role means that it is usually only part-time. The role of programme manager is likely to be full-time and deals with the day-to-day co-ordination of the programme.

In the Canal Dreams ebooking enhancement project, the booking application may be one of a portfolio of projects. Canal Dreams may wish to expand and diversify their business by extending the types of holidays that they have on offer to include, for example, rented cottages or boating holidays abroad. This would require ebooking transactions with slightly different functionalities to be developed. A co-ordinated approach to implementing these varying requirements would seem to need some kind of a programme to be initiated.

8.3 IDENTIFYING STAKEHOLDERS AND THEIR CONCERNS

A stakeholder is defined as anyone with a valid interest in an IT project or the products delivered by it. This group includes:

- all project personnel including managers, designers and developers;

- users, sponsors and other members of the organisation affected by the project;

- suppliers of software, hardware, consultancy, etc. to the project;

- contractors and subcontractors;

- members of the business community and, of course, financial backers.

Part of the project initiation process is to establish who these people are and to identify their needs and concerns. Processes will have to be set up to ensure that their interests are represented and that they are consulted and kept informed.

ACTIVITY 8.1

List the main stakeholders in the Canal Dreams ebooking enhancement project.

8.4 THE ORGANISATIONAL FRAMEWORK

A formal management structure is needed with defined project roles:

- Named personnel should be allocated to the roles – but several people may share a role and a single person may have more than one role.

- Roles must carry appropriate authority and responsibility.

- Individuals must carry out their roles correctly and willingly and must clearly understand their objectives.

- Status within the organisation is not sufficient qualification for a particular role. Previous experience and/or training in the role is needed.

At the top of the project organisation is a project sponsor. This person would be a senior person within the organisation who would be able to champion the project at an appropriately high and influential level – normally board level. Crucially, the sponsor controls the funds to pay for the project. Below the project sponsor is the following structure:

- project board (or steering committee or project management board);

- project manager;

- stage manager;

- project team leader;

- team member.

In parallel to this structure are three other functions:

- project assurance team;

- project support office;

- configuration management team.

Most of these titles are based on the PRINCE2 terminology, so whether or not they exist within a particular project organisation will depend on the extent to which the organisation embraces the PRINCE2 approach. However, the roles that they represent should be present in all projects to a greater or lesser degree, although they may have different names. Where a project is small, for example, the project manager, stage manager and project team leader roles could be carried out by a single person.

Having established who the project sponsor is, it is necessary to establish a body to control the project – the project authority. The British Standards Institution’s Guide to project management (BS 6079) states that the authority for a project lies with the project sponsor. In PRINCE2, the Project Board performs this role. Project boards become more important with larger projects that have many influential stakeholders. It must be made clear who has the ultimate responsibility for the project – inevitably, this will be whoever holds the purse-strings.

8.4.1 Project board

The Project Board provides a forum in which critical issues can be discussed and decisions taken which are outside the remit and competence of the project manager. If PRINCE2 is not being followed, the same function may be served by a steering committee or a project management board. This group should include the project sponsor or their representative. In PRINCE2 terms this person is known as the Executive and is joined by a Senior User and a Senior Supplier, although in certain circumstances the Executive and the Senior User could be the same person.

Members of the board must be able to make decisions for their areas of responsibility without having to refer to higher authority. If they are at too low a level they will constantly be referring decisions back to their managers, which can delay the project. It can also be a problem if they are at too high a level, as important and busy staff may attend meetings infrequently, leading to ineffective decision-making.

All projects should derive from the organisation’s business strategy and be designed to meet specific business and corporate objectives. It is therefore the role of the Executive, apart from looking after the money, to ensure that the project:

- stays in line with the corporate objectives;

- meets the business requirements;

- retains its business case (that is, that the benefits continue to outweigh the costs of the project).

The role of the Senior User is to safeguard the interests of the users and make sure that their requirements are met. He or she will be responsible for ensuring that the user requirements have been captured and deliverables have been signed off as acceptable. With the best will in the world, requirements will change over time. The Senior User must therefore ensure changes to requirements are in line with the business needs, can be justified and do not jeopardise the project as a whole. As was seen in Chapter 4, perfectly valid changes can delay the project to such an extent that it will not deliver the expected benefits.

The role of the Senior Supplier includes ensuring that adequate technical resources, in terms of both skilled staff and the software and equipment that they need, are available to the project. They should also support the development team and, when necessary, represent their interests as difficulties arise, for example in the face of continual change requests.

If all or part of the project is contracted to an external supplier, the Senior Supplier should come from that organisation. If there are a number of contractors then more than one supplier representative may be required. However, this could detract from the main purpose of the Project Board and therefore it may be more effective to set up a separate group to manage the external suppliers.

The quality assurance function could also have a representative on the board or may report via another member of the board, usually the Executive.

If the project is large, it may be necessary to have several user representatives. Similarly, if it is geographically dispersed then additional representatives may be required. Care must be exercised to ensure that the board does not get too big and thus become ineffective. Subgroups may have to be set up to give a voice to all those who should have one, without detracting from the efficient working of the board. This is always a balancing act, but smaller groups are usually more effective when it comes to decision-making.

The infrastructure management of the business, responsible for the platforms on which the delivered IT system will run, may also be represented. If the development staff have a different manager to the infrastructure support staff there could be a conflict of interest between the two. However, infrastructure management is often represented through the Senior Supplier.

The Project Board is a decision-making body. It holds the purse-strings through the Executive and therefore has ultimate control of the project. The project manager would normally be appointed by and report to the board. The board establishes the terms of reference and provides the management framework within which the project manager operates. It is the final arbiter on whether the project has met its objectives. In summary, the board initiates the project, controls its execution and eventually closes it down. It approves the following:

- project terms of reference (including the project initiation document);

- business case;

- budget;

- project plans;

- changes to project plans;

- quality plans, control and assurance processes;

- risk assessment and contingency plans;

- major changes to project requirements.

It receives feedback on the progress of the project from the project manager and also from the quality assurance function. The feedback enables them to sign off each stage of the project or other activity as defined in the plan, or require that it be reworked. It thus exercises overall control of the project.

8.4.2 Project manager

The project manager is pivotal in the organisation of the project and has overall responsibility for the day-to-day management of the project. The role of the project manager is to ensure that the project is delivered on time, within budget and to the specified quality. A daunting task!

The project manager produces, with the help of others, the various plans for the project (see Chapter 2). Monitoring progress against the plan and making adjustments are ongoing for the duration of the project. As milestones are reached, progress will be reported to the board and team members (see Chapter 3). The project manager is set tolerances for activity completion and costs within which to work. Any deviation in the plans likely to take the project outside these should be reported to the board with recommendations about the actions the project manager feels are necessary to correct the situation or to mitigate its effect.

Inevitably, changes come along; the project manager assesses their impact on the project and reports to the board. It is the responsibility of the board to decide whether or not changes should be implemented although, as seen in Chapter 4, this responsibility may be delegated, within constraints, to a change control board.

Should a risk materialise, the project manager will approach the board for permission to put into effect the agreed contingency plan. Logs of both change requests and risks are kept (see Chapters 4 and 7, respectively). The project manager has the responsibility of making sure that they are kept up to date.

Because project managers have to lead their projects, they must be able to set clear goals so that those who report to them are aware of what is required. The simple production of plans and schedules does not by itself achieve this.

8.4.3 Stage manager

In larger projects, someone may be appointed to the position of stage manager. This role is similar to that of the project manager but is specific to the particular stage. Detailed plans, work schedules and monitoring then become the responsibility of the stage manager rather than the project manager. This does not mean that the project manager gives up all responsibilities; more that much of the routine work is carried out by someone else, who may have particular technical expertise in dealing with a particular stage. The project manager is still responsible to the board for the progress and success of the project.

The appointment of stage managers appears to be rare as team leaders are usually able to carry out these team leadership roles. The Stage Manager role has therefore been dropped from more recent versions of PRINCE2.

8.4.4 Team leader

Team leaders are close to the action. A team leader may be responsible for a specialist group of analysts, designers or programmers and hence work on a very specific part of the life cycle. Alternatively, a team leader may lead a mixed team, in which case the responsibilities would encompass the whole of the life cycle. A team leader usually needs technical experience and knowledge. One very specialised area is that of testing, where a team becomes expert at the creation of test data based on the requirements specification, which is then run through the software to see whether or not they meet those requirements.

Team leaders have the task of allocating authorised work packages to specific individuals and helping them to complete the activities within the scheduled time scales. They also act as mentors or advisers when necessary. They will be most aware of how well a particular part of the project is going. They should be able to quickly notify the project manager of delays so that action can be started to bring the project back on course before it goes seriously adrift.

8.4.5 Team member

At the bottom of the pile is the team member. However good the structure may be, without competent team members the project will not succeed. Ideally, project managers should be able to select their teams. This is rarely possible, so the project manager has to be familiar with the qualities of the staff allocated to them and assign them to the tasks which most match their capabilities. In larger organisations in which team leaders or stage managers exist, they may undertake this task or share it with the project manager.

As we will see in the section on matrix management, specialist staff often have only a short-term project relationship with the team leader, while their longer term development and deployment is the responsibility of a separate technical head.

8.4.6 Project assurance team

This is usually a function rather than an actual team. The project board could fulfil the role. However, depending on the size and nature of the project, it is normally delegated to one person or a small group. The tasks are the same; it is just the degree of activity that differs. Members of the project assurance function are appointed by and report directly to the project board, not to the project manager. Their role is primarily quality assurance (see Chapter 5). They are responsible for checking that the quality control activities in the quality plan are carried out, standards are observed and procedures are followed. Being independent of the project manager, they can give an objective view on the quality of the products delivered and not just the timeliness of their arrival.

In the early stages of a project, the team would contribute to the setting of standards, the creation of procedures, the establishment of the quality review and quality assurance processes and the quality plan. This is particularly useful if the project is venturing into areas of technology that are new to the organisation.

A large, complex IT project may need several people for this activity, each with their own specialism, such as security. Three specific roles sometimes identified are:

- business assurance co-ordinator, who would, for example, make sure that the IT application under development is compatible with existing business procedures;

- technical assurance co-ordinator, who would ensure that the operational environment is not compromised by the new system;

- user assurance co-ordinator, who ensures the application meets user needs.

ACTIVITY 8.2

In the Canal Dreams ebooking enhancement project, the main driving force behind the new internet-based booking system is the managing director. He has given you a contract to manage the project. You are in regular contact with the manager of the telesales call centre, local boatyard managers and the directors of marketing and of finance. You also need to communicate regularly with the IT infrastructure manager at Canal Dreams. The software is to be supplied by the XYZ software house and you have had several meetings with one of their account managers. Identify which type of role on the Project Board would be likely to represent each of the various stakeholder groups in the scenario.

8.5 DESIRABLE CHARACTERISTICS OF A PROJECT MANAGER

The role of the project manager is pivotal. IT project managers have traditionally progressed from technical areas such as software development through system design and team leadership to project management. This, however, may be changing, as the project management role nowadays often involves managing the external suppliers of services. Thus, while it is useful to have a good technical background this is not always essential in order to manage an IT project.

It is more important to have other skills and characteristics. A key quality is good communication skills at all levels. The project manager may need to present to higher management a convincing case for a course of action. Stakeholders have to be kept informed and the project teams must be motivated. If project managers are to gain the respect and confidence of those around them, they have to be effective communicators, good managers and effective organisers.

They need to have skills in:

- leadership;

- motivation;

- planning;

- negotiation (being firm, flexible, and able to compromise where appropriate);

- delegation.

They need to be:

- responsible;

- reliable;

- available (not just for this project but contactable at all reasonable times);

- intelligent;

- sociable (able to mix well);

- approachable (they should be good listeners);

- knowledgeable in the business area for the particular project.

These characteristics do not just arrive with seniority. A potential project manager must possess some of these attributes and will need development in deficient areas before becoming fully effective.

Although this list may seem daunting, the ability of people who seem quite ‘ordinary’ to become competent project managers through application, self-discipline and appropriate training is remarkable.

8.6 PROJECT SUPPORT OFFICE

The qualities we have associated with project leadership seem heroic, but projects have many mundane clerical activities which have to be performed regularly, effectively and efficiently. The project manager is accountable for them, but given the pressures on project managers, it is more effective to delegate these tasks. This gives rise to what has become known as the project support office (PSO).

The organisational structure that has been described above is usually set up for a specific project. This means that the project board and project manager are appointed for a single project. The project support office, on the other hand, may be to a greater or lesser extent a permanent organisation which supports several often inter-related projects. In these cases it is convenient to combine project support with programme support – hence we have a programme and project support office (PPSO) or simply a programme management office (PMO).

The precise tasks this office undertakes will vary, but the following list is typical:

- time recording;

- updating of project plans;

- risk log maintenance;

- issues (change) log maintenance;

- arranging meetings;

- issuing agendas;

- taking minutes;

- chasing actions;

- configuration management.

8.6.1 Time recording

Time recording is essential for project control. Clerical staff can collect and process the information required. The team leaders or project managers should be aware of what is happening but, relieved of the routine work, they can focus on checking that effort expended is consistent with that expected and, if not, take the necessary action.

8.6.2 Updating plans

As details of progress are passed to the PSO, staff can update the plans and highlight problems to the team leader or project manager. In the event of changes to project team membership, the PSO can revise the plans so that the project manager is aware of the impact of such changes and can make any modifications necessary or alert the board to potential problems.

8.6.3 Maintenance of logs

The PSO can maintain project logs. The project manager can be warned of approaching risks via the risk register (see Chapter 7). Risks that have passed can also be noted. Requests for change (RFC) are recorded as they arrive and then passed on for action (see Chapter 4).

8.6.4 Arranging meetings

A great deal of time, most of which involves finding dates and times at which all parties are available, can be spent on arranging meetings. Aids such as electronic diaries make this easier, but it can still be time-consuming. Delegation to the PSO is natural. Having agreed dates and times, the PSO can:

- organise the necessary room and other requirements such as catering;

- issue the agenda – most meetings have a set agenda and it is simple to check with the chair of the meeting to see if any changes are required;

- circulate other documents needed – the PSO may already carry out the configuration control function which controls the versions of documents;

- record and distribute the minutes of meetings – the key thing is to ensure that all actions are identified, along with who is responsible for carrying them out and in what time frame.

8.6.5 Configuration management

The whole of Chapter 4 has been given over to change control and configuration management. The ability to keep track of documents and products to ensure that everybody is working with the latest version is very important to the success of the project. Like the PSO, within which it may function, configuration management has a life beyond the duration of the project, as the delivered IT system will continue to require amending and updating until it is finally replaced.

8.7 PROJECT TEAM

‘A project team is defined as a small number of people with complementary skills who are committed to a common purpose, performance, goals and approach who are directly or indirectly accountable to the project manager.’

Michael W. Newell and Marina N. Grashina, The Project Management Question and Answer Book, American Management Association, 2004.

Project teams work in a different way from operational staff. A project team is brought together for the sole purpose of achieving the project objectives. On completion of the project, the team is disbanded. Team members may be drawn from a specialist division within the organisation, such as the IT department, to work on the project and may be assigned to other projects when it is over. Others may be drawn from functional departments and will go back to their original jobs at the end of the project. The impact of being in a project team will be quite different for the two types of people, as will their expectations during and after the project.

Project team members are not always located together, although this is best. If the team is drawn from different departments, they could be located in different parts of the country. It may be possible to bring them together for short periods. However, they could be located in different countries, which would make that much more difficult. Part of the solution to these problems could be matrix management.

8.8 MATRIX MANAGEMENT

So far it has been assumed that all staff report to the project manager, either directly or through team leaders or stage managers. This is the best way of managing a project but is not always practical, particularly if team members are drawn from a variety of departments.

Senior staff on a project – that is, the stage managers and team leaders where they exist – should always report to the project manager. If this is not the case the exercise of managerial control may be weakened to a point where it would be impossible, with any certainty, to keep to a delivery plan.

In matrix-managed teams, an individual reports to more than one person. One example of matrix management can be found on board a naval ship. The captain of the ship has overall responsibility for everything that happens on the ship when it is at sea. Its complement of sailors will include navigators, engineers, electricians, cooks, medical staff and others. Each specialised trade will also have a shore-based manager to whom they will report and who is responsible for their performance on the ship and their training when ashore.

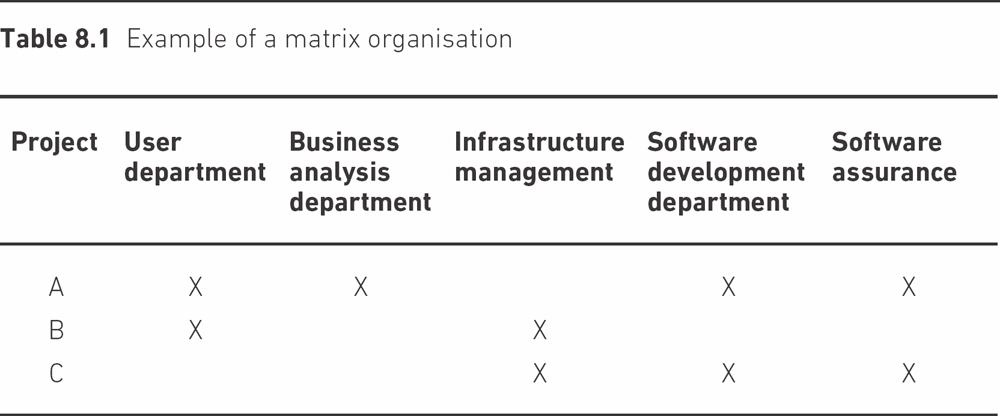

In any organisation, it is probable that a number of projects would be under way at the same time, each requiring a range of different skills. For example, business analysts may help to elicit requirements from the users and ensure that they are clearly understood by the technical members of the project team. Analysts and designers would then be required to convert the requirements into a design specification. They could well be part of a specialist department within the organisation and report to a separate manager. There is likely to be another department which manages the IT infrastructure. They could second someone to the team to look after their interests and guide the designers so that the proposed solutions are compatible with the existing structures.

The developers (or programmers) may be part of a separate pool of development specialists, or even come from a specialist group outside the organisation. The testing team may come under a different department with its own line management. Putting all these together gives rise to a matrix structure as shown in Table 8.1.

This sort of structure has the advantage that the project manager has a team of specialists and can concentrate on the project in hand and not be concerned with issues such as the long-term development of the staff involved, as this would be the responsibility of the line managers. The big disadvantage is that the line managers may call their staff off the project for some more urgent task because of an unforeseen event such as staff illness, making planning and control more difficult. These issues should be discussed at the beginning of the project and a strategy agreed by the project board, to which all line managers sign up.

Even where all staff, including the project managers, work for the same line manager, they could be allocated to more than one project. Each person may have their own perceived priorities and may put more effort into one project than another, perhaps because one task is easier or more interesting or more rewarding. This can lead to slippage on some projects, while others progress to schedule.

We noted in Section 8.2 that where there are many projects being carried out at the same time, particularly if they are related, there is often an umbrella organisation known as programme management. Where resources are limited, which is the normal situation, a programme board would have the remit to make the final decisions about the allocation of resources between projects. While this may be irksome for the individual project manager, it is to the benefit of the organisation as a whole. Obviously plans have to be revised to take account of this situation and project managers cannot be held responsible for delays to their projects due to such changes.

With matrix management, the level of control that the project manager will have over the project team will vary. Where an individual is seconded to the project for its duration then the project manager has greater control – as with the ship’s crew. This is in many ways the ideal, but it does have its drawbacks. With every project, the level of resource required will vary over time. For example, in the early, analysis stages of a project, several analysts but only one part-time designer may be required. However, as the analysis phase is completed, more designers may be required, but fewer analysts. If these staff were permanently with the project they would be under-utilised at times, adding unnecessary costs to the project.

ACTIVITY 8.3

List the types of people (including external suppliers) required to implement the Canal Dreams ebooking enhancement project.

8.9 TEAM BUILDING

A team in an IT project is usually a collection of specialists with a requirement to work together towards a common goal. It is usual for the composition of the team to be based on a number of compromises; it will never offer the ideal combination of skills and personal characteristics. Making the group of individuals into an effective team is an interesting and rewarding management challenge. There are many commonsense aspects and a number of theoretical approaches to developing an effective team.

The Tuckman-Jensen model describes four basic phases through which a team goes before it becomes fully effective:

- Forming. The group members have just been brought together and are probably hesitant about their new environment, unsure of their new colleagues and possibly nervous about future developments. Members are polite to one another, tend to accept authority and tread carefully. Some initial contact with colleagues reveals common ground and possible allegiances.

- Storming. Individuals within the group have started to assert themselves and to form alliances. Conflict may arise as ‘pecking orders’ become established. Aims and objectives are becoming clearer but there are different views on how to proceed with the tasks ahead. Members now have a sense of belonging to a team, are gaining confidence and are likely to challenge the proposed methods of working.

- Norming. Internal conflicts are hopefully resolved and the team members feel more comfortable and relaxed with their colleagues and their new surroundings. An acceptance of common values and behaviours develops, with open communication and constructive cooperation. The team starts to work as it should, with its overall capability being greater than the sum of its parts.

- Performing. The team is fully functional and has become a cohesive unit. Team morale is high, with good cooperation between members and a shared responsibility for the common goal. Team members are working hard and getting satisfaction as the team achieves its goals.

A fifth stage, adjourning, is sometimes added to describe when the team breaks up at the end of the project. The Tuckman-Jensen sequence of phases clearly represents the ideal team development. Good team leadership and people management are essential to allow the team to progress through the phases, and indeed the final stage may never be achieved if the personnel or the project circumstances are not right. It is quite possible to slip back a stage or two if unexpected developments are not well managed – for example:

- changes in team personnel – new arrivals can disrupt team morale and stability;

- a change in direction of the project, which means much team effort has been wasted;

- a change of leadership, which may mean the team needs to adapt to a new management style and could revert to the storming stage.

8.10 TEAM DYNAMICS

Building a team involves finding people with the appropriate skills who are available when you need them and are motivated to perform the tasks required of them. However, if the team are to work well together, a satisfactory mix of personality types and personal attributes is essential. A system for analysing and categorising people’s personal characteristics was developed by Belbin, who defined nine team roles:

- Shaper – an energetic team member with a strong need for achievement who drives the team along;

- Plant – a creative and innovative team member (the term ‘plant’ is used because it was found that planting such a person in an uninspiring team was a good way to improve its performance);

- Resource investigator – a team member who makes contacts outside the group to bring in ideas and information and to acquire materials/resources;

- Co-ordinator – a chairperson who promotes decision-making and delegates well (not necessarily the team leader);

- Monitor evaluator – a team member who is analytical and able to assess ideas and options but is not creative;

- Team worker – a team member who helps to maintain team spirit and cohesion;

- Completer finisher – a conscientious and painstaking team member who is concerned with getting things finished (this is a very important team trait);

- Implementer – a team member who attends to details, is hard-working and organises the practical side of the project;

- Technical specialist – someone who can provide the team with technical expertise.

![]()

COMPLEMENTARY READING

For further details, see R.M. Belbin, Management Teams: why they succeed or fail, 2nd Edition, Elsevier, 2003

It is not suggested that a team has to have one person of each type or that each team member falls into only one role. An individual can have attributes from a number of different roles. The idea is that a team needs a satisfactory mix of roles played by its members to perform well. A Belbin analysis may help to define a team weakness, or indeed to clarify the reasons why a team is not performing well or why conflicts keep arising in an otherwise skilled, competent team.

8.11 MANAGEMENT STYLES

There are as many styles of management as there are managers. The different styles and approaches depend as much on the personality and capability of the manager (or leader) as on the environment and the prevailing circumstances. The manager may well have a natural preference for a certain style, but will have to vary their approach depending on the circumstances in order to be successful.

For example, a task-orientated leadership style is sometimes distinguished from a relationship-orientated leadership style. Task orientation focuses on the technical aspects of the work, while relationship orientation emphasises such things as individual motivation and team morale. When a team is developing – the forming stage – it will need more direction than when it is fully functioning – the performing phase. A task-orientated approach would be more effective than a relationship-orientated approach because the team members are not yet familiar enough with the tasks to be carried out and the environment in which they are to be carried out.

This distinction between task orientation and relationship orientation overlaps with that between autocratic and democratic styles of management. When staff are new to a project a more autocratic approach may be called for, as staff are not yet sufficiently knowledgeable to be involved in complex decision-making. Individual team members will react differently to these two approaches. Some people prefer to have clear direction and to leave decision-making to others, whereas other team members like to feel they have a part to play in establishing the direction of the project and wish to provide an input to the decision-making process. An intermediate approach is described as consultative.

- Autocratic management provides clear direction and quick decisions. The leader is seen to be decisive, firm and effective. However, it can be synonymous with an uncaring, remote, unapproachable, controlling or bullying management style. An autocratic leader can demotivate a team that is working in a climate of fear (members may seek an alternative project).

- Democratic management shares responsibility for decision-making and for the team’s performance: thus the team is likely to be more committed to the project. This style can be perceived as weak and management can be seen as avoiding responsibility for difficult decisions. It may be difficult to enforce discipline if conflicts develop.

- Consultative management seeks the opinions and views of the team prior to a decision being made. Although team members are consulted, the final course of action may or may not reflect their views. Consultative management is seen as a compromise between autocratic and democratic management, with the benefits, and possibly the pitfalls, of both.

A politically acceptable and effective manager would need to stay away from extremes and be able to adapt styles of management to the situation and the people involved. Ideally such a manager could be decisive and effective where a quick decision was required and approachable and consultative on other occasions, and thus gain commitment from the team where joint decisions and consensus were appropriate.

Whichever approach is used, the project manager must be an accomplished communicator and have the ability to use the most appropriate methods of communication in order to be fully effective.

8.12 COMMUNICATION METHODS

Methods of communication for IT projects can include:

- memos;

- newsletters;

- meetings;

- noticeboards;

- presentations;

- progress reports;

- telephone conversations;

- text messages;

- email messages;

- letters;

- drawings;

- one-to-one conversations;

- video conferencing;

- intranets and extranets;

- social networks.

Methods can be categorised as active or passive and as formal or informal. Active methods, such as a telephone conversation, require a response or reaction so that there is reinforcement or confirmation that the information or message has been received and understood. Passive methods such as a newsletter require no such confirmation. They leave to chance whether anyone reads or understands the material and should not be used for important messages.

Formal methods of communication have a set structure, such as a meeting of a project board, in contrast to informal methods such as a conversation, which carries no particular format and is not usually recorded.

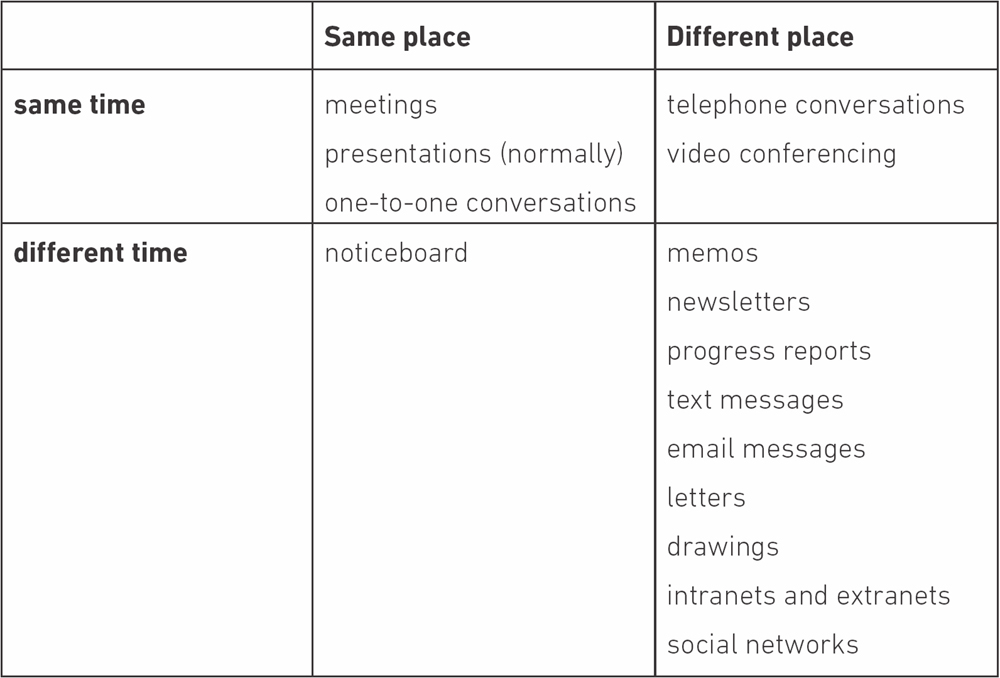

It is also possible to categorise methods depending on whether the participants have to be available at the same time and/or in the same place for communication to take place.

ACTIVITY 8.4

Categorise each of the methods listed above as same time/same place, same time/different place, different time/same place, or different time/different place.

By categorising methods in this way it is possible to assess the suitability of a particular method. It is best to put together a communications plan setting out the methods of communication that should be used during the project for each set of circumstances and exactly how they should be applied. For example, you may decide that a short weekly face-to-face meeting (an active, formal method) with the project sponsor would be better than an email.

By setting out a detailed communications plan with all stakeholders, rather than leaving things to chance, you stand a much better chance of getting it right. Below is an example of an entry for one of the types of communication selected for a project:

| Name/description | Joint application development session | |

| Target audience | User representatives and business analysts | |

| Purpose | To elicit user requirements | |

| Frequency/event | 23rd April | |

| Method of communication | Away day | |

| Responsibility | Ann Smith (Project Manager) |

8.13 CONCLUSION

This chapter has only been able to touch briefly upon some aspects of organisational behaviour as it relates to projects. A good book on the important issues of organisational behaviour that goes beyond the immediate demands of the BCS Foundation Certificate in Project Management for Information Systems is:

![]()

COMPLEMENTARY READING

John Arnold, Cary Cooper, and Ivan Robertson, Work Psychology: Understanding human behaviour in the workplace (4th Edition), FT Prentice-Hall, 2004

SAMPLE QUESTIONS

1. Which of the following is not a name given to the group which has responsibility for committing resources to the project and approving variations to the project’s objectives?

(a) project board

(b) project management board

(c) project support office

(d) steering committee

2. Which of the following terms is used to describe an organisational structure where staff are responsible to a project manager for the duration of a project but also have a manager who is responsible for their long-term staff development and work programme?

(a) the Tuckman-Jensen model

(b) configuration management

(c) matrix management

(d) task orientation/relationship orientation

3. At which stage of team formation does a team become fully functional as a cohesive group?

(a) performing

(b) norming

(c) storming

(d) forming

4. Which of the following is an example of different time/different place communication?

(a) a project board meeting

(b) a checkpoint report

(c) a telephone conversation discussing a problem a user has with an IT system

(d) video conferencing with the supplier of a software application

ANSWERS TO SAMPLE QUESTIONS

1. (c) 2. (c) 3. (a) 4. (b)

POINTERS FOR ACTIVITIES

ACTIVITY 8.1

Stakeholders in the Canal Dreams project include existing IT support staff, customers, boatyard staff (who will be checking in customers at the start of their canal holiday), current telesales booking staff, the managing director, the marketing director, the central finance department, the personnel department, the premises manager (who has to find room at head office for a network support centre), IT equipment suppliers and software suppliers.

ACTIVITY 8.2

The Senior User represents the interests of boatyard staff, telesales booking staff and the marketing and central finance department.

The Senior Supplier reflects the views of existing IT support staff, IT equipment suppliers and software suppliers.

The Executive represents the interests of the managing director and the marketing director (who may be the member of the senior management team with the strongest interest in the project).

It could be argued that the personnel department, who will have to recruit new network support staff and perhaps relocate existing staff as a result of this project, and the premises manager, who will have to find accommodation for the new network support centre, are suppliers of services to the project.

Who will represent the interests of the customers of Canal Dreams? It may be the marketing department, who may have conducted market research into the preferences of potential customers, or the booking and boatyard staff, who have had most contact with customers in the past. These would be represented on the project board by the Senior User.

Note that terms like ‘Senior User’ simply represent roles, and more than one person might undertake that role. Each project must form a project board with representation that is sensible for that project.

ACTIVITY 8.3

- Users;

- Analysts;

- Designers;

- Database designers;

- Network/telecommunications specialists;

- Hardware specialists;

- Software developers;

- Testers;

- Trainers.

ACTIVITY 8.4