CHAPTER 24

Foldback

The performing environment for the musicians. Constant voltage distribution systems. Impedance calculations. Stereo vs mono. Mixing by the musicians. Types of headphones. Advantages of different options.

A very important aspect of any recording studio is its monitoring environment, as this is the means by which all the studio proceedings are ultimately judged. However, it should not be forgotten that there is another very important monitoring environment; the foldback system. When musicians are using foldback, it is their world. The acoustic sounds of the studios, the real sounds of the instruments, or the sounds as heard by the recording engineers in the control rooms are all only peripheral concepts to a musician wearing headphones. What is of utmost importance to a performance at the time of recording is the ambience created for the musicians in the foldback systems. This subject was introduced in Section 9.3, which may be worth re-reading before beginning this chapter.

24.1 A Virtual World

In large studios, ‘tracking loudspeakers’ are sometimes used, as shown in Figure 24.1, but only certain types of room lend themselves to being optimally usable with this form of foldback. The system has always been popular because many musicians prefer not to use headphones if they can avoid it. Some of this is no doubt because our perception via headphones is different from our perception via our pinnae (outer ears), and musicians tend to like to perform in a familiar world. However, it could well also be that many musicians have shunned the use of headphones not only because they find them to be an unnatural ‘world’, but also because they have too often had to endure some pretty appalling foldback mixes.

To an alarming number of recording personnel, foldback is something via which a musician keeps in time and in tune to a backing track, and little else. To musicians, the foldback is their creative space. Badly balanced foldback will distort the musicians’ perception, and nobody can be expected to perform with appropriate expression and feeling if they are not hearing a balance which is conducive to such a performance. A musician cannot be expected to build up a feel for a track if levels are going up and down, and instruments are cutting in and out as recording engineers adjust their balances, while hoping that the musicians can use such run-throughs for their own rehearsals. Musical performances can be fragile, and this fact should be taken into account before any atrocities are committed via the foldback.

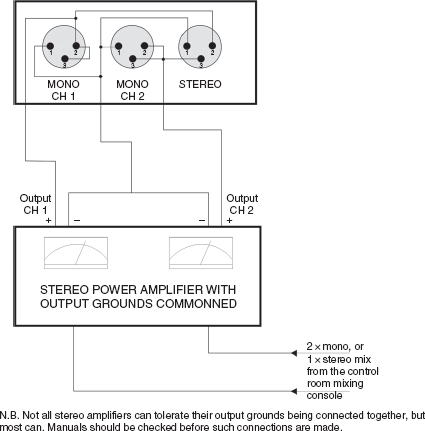

Figure 24.1:

Use of tracking loudspeakers. In this situation, a directional microphone is used to record the vocalist, with a loudspeaker providing the foldback. A typical arrangement would be for the loudspeaker to be placed directly behind the microphone and pointing towards an absorbent surface in order to control the amount of reflexions of the foldback signal returning to the front of the microphone.

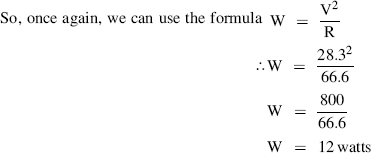

24.2 Constant Voltage Distribution

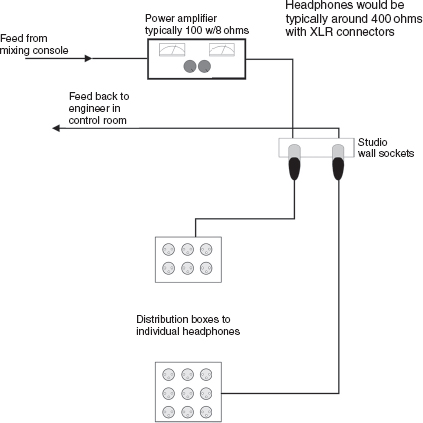

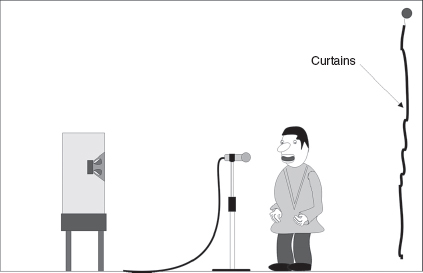

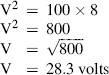

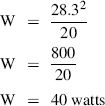

The time-honoured tradition of providing foldback in many large studios has been to use a power amplifier as a constant voltage source, and to use medium impedance headphones to bridge the line. Such a system is depicted in Figure 24.2. The principle of such a system is to take a feed from the auxiliary output of the mixing desk and to feed this into the inputs of the amplifier. The amplifier gain control is usually set such that 0 VU from the desk would produce about 3 dB below clipping at the output terminals of the amplifier. For a typical amplifier producing 100 W into 8 ohms, the output voltage at full power would be given by the formula:

![]()

where:

W = power in watts

V = voltage in volts

R = resistance (or the impedance for a complex load) in ohms

Figure 24.2:

Constant voltage foldback system. NB: if individual volume controls are used for each set of headphones, they should be potentiometers of about 600 ohms, linear track and should each be capable of dissipating at least 5 watts, or they will tend to burn up.

∴ For 100 watts into 8 ohms, the voltage would be:

To be 3 dB down on this would be half power, so:

(Note: 3 dB down is half power, 6 dB down is half voltage)

The output from a typical power amplifier is referred to as a constant voltage source because when an input voltage causes an output voltage to appear at the loudspeaker terminals, differing load impedances do virtually nothing to cause the voltage to vary. At least, that is, until an impedance is reached which is so low that the amplifier power output becomes limited by its ability to supply current into the load, when either the voltage will begin to sag or protection devices cut in.

From the formula W = V2/R it can be seen that if the voltage remains fixed, then changing R will change W. In fact, reducing R will always increase W. That is, if the voltage remains fixed, if the resistance (or impedance) goes down the power will go up. The power output is thus dependent upon the load impedance. As more headphones are added in parallel to such a foldback circuit, the impedance of the load to the amplifier will drop, and it will be able to supply proportionately more power. (See Glossary for a discussion on resistance and impedance.) If headphones of suitable impedance are chosen, then it can be ensured that they cannot be overloaded if the inputs (from the mixing desk outputs) are inadvertently turned up excessively, or if a feedback should occur.

A typical studio headphone would be something like the Beyer DT100. Each capsule has a maximum power rating of 2 watts, and they are available in a variety of impedances from 8 ohms to over 1000 ohms. A common value for studio use is 400 ohms. It was calculated earlier that an amplifier rated at 100 watts into 8 ohms could give a maximum output voltage of 28.3 volts. If 400 ohms is substituted into our above formula, it can be seen that such an amplifier could deliver, at maximum:

i.e. 2 watts (into a 400 ohm load).

Consequently, even if driven to maximum output voltage, the amplifier could not deliver enough power to destroy the headphones.

If six headphones were used, the combination of six 400 ohm loads in parallel would give a total impedance of:

![]()

Twelve watts into six headphones is still 2 watts per headphone.

Making the same calculation for 20 headphones, 20 × 400 ohm loads in parallel would give 400 ohms ÷ 20 = 20 ohms

which, divided by the 20 headphones is, yet again, 2 watts per headphone.

It can thus be seen that if the headphone impedance is correctly chosen the amplifier will simply provide more current (and therefore more power) as the number of headphones is increased; at least until the maximum output rating of the amplifier is reached. However, below this limit, adding more headphones will not affect the loudness of any of the headphones already connected, nor will there be a risk of burning out headphones if other parallel devices are disconnected, because for any given input signal, the peak output voltage remains constant, and independent of load impedance.

Nevertheless, one precaution which is worth taking with such systems is to feed the foldback amplifiers via un-normalled jacks on the jackfield/patchbay so that they must be patched in when needed. All too frequently, people wire them via jacks that are normalled to the auxiliary outputs of the console. During mixdown, when the auxiliaries are being used to drive effects processors, headphones are often unintentionally left connected in the studio. When the effects processors are plugged into the half-normalled auxiliary outputs, the feeds to the amplifiers are not disconnected, so the high levels which are being sent to the effects units will also be feeding the foldback amplifiers. Although the amplifiers may not be able to overload the headphones with clean power, if the amplifiers do overload, then the distorted signal waveforms continuously running into the headphones may destroy the capsules after some time of such abuse. However, by making it necessary to physically patch the amplifier inputs into the auxiliary outputs when foldback is required, the headphones will automatically be disconnected when the auxiliaries are needed for other purposes, and damage to the headphones will be prevented.

With the type of foldback system under discussion here, all the feeds are sent from the auxiliary outputs of the mixing console. As all the headphones on one circuit share one amplifier, the foldback balance is thus entirely in the hands of the recording engineer. It is usual for the engineer to be provided with a headphone socket in the vicinity of the mixing desk, fed from the same amplifier output so that he or she will always be able to check, at any time, the exact balance and level that is being fed to the musician(s). In order to optimise this facility, it is the usually preferred method for the engineer to use identical headphones to the musicians.

Of course, not all of the musicians want to hear the same mix, so multiple foldback systems are often provided. Drummers may need to hear lots of bass but little drums in the headphones, whilst bassists may need to hear lots of drums and little bass. No matter how many systems are in operation, there would be a feed from each one back to the engineer, so that the balance can be carefully set on each channel in the sure knowledge that the musicians will be hearing the selfsame sound.

24.3 Stereo or Mono

Without doubt, a stereo foldback presentation is easier for musicians to work with compared to an ‘above the head’ mono jumble. In general, because of the spacial separation, individual instruments can be readily detected in a stereo mix even if their level in the mix is on the low side, or if they are in a frequency range which is shared by other instruments which are playing at the same time. Nevertheless, mono foldback is still common, especially when multiple mixes are needed, as there may not be enough auxiliary outputs or foldback channels to send stereo feeds to everybody. Mono mixes usually require much more delicate balancing if the musicians are to hear the detail that they need, and it is often wise not to send unnecessary instruments to the mix. Simplicity can be the key to clarity in mono mixes.

Some recording engineers, when overdubbing, send a stereo feed to the foldback which is derived from the monitor feed in the studio, plus a little extra boost on what is being recorded. This system can work well, but it must be done in such a way that any muting or soloing on the main monitors does not affect the foldback, or it can be very disturbing and frustrating for the musicians. It may also, at times, be an inappropriate balance, because perception via headphones can be very different to perception via loudspeakers. Once again, though, if the engineer has a headphone feed from the same power amplifier output that feeds the musician’s headphones, then the appropriateness of the balance can readily be checked.

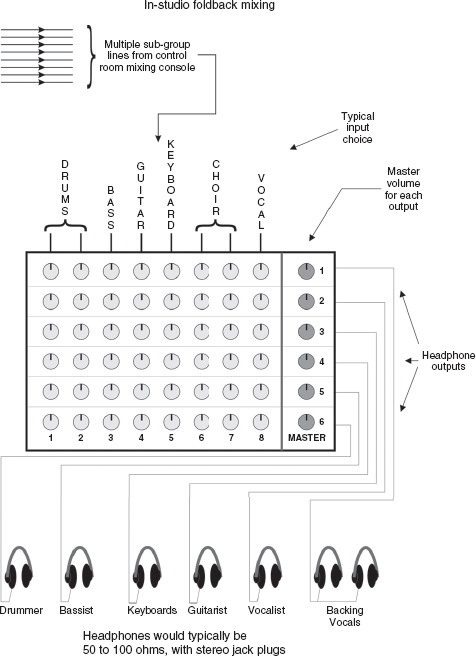

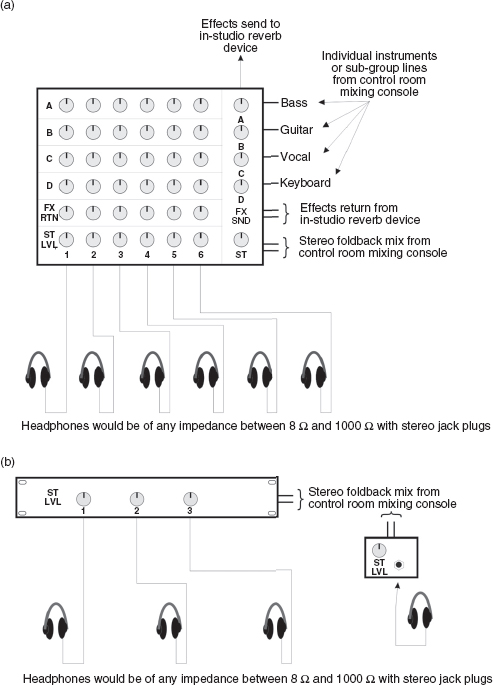

24.4 In-Studio Mixing

An alternative foldback philosophy to the one outlined in Section 24.2 sends line-level sub-group outputs to the rooms where the musicians are recording, and small mixers are provided for each musician, or group of musicians. Three variants of this concept are shown in Figures 24.3 and 24.4(a) and (b). By this means, sets of sub-groups such as drums, guitars, keyboards, vocals, brass and other such sections can be sent to the studio, where the musicians can set their own balance and level, at least to the degree that the subgroups can provide discrete feeds. Whilst this may sound like an ideal system, with much greater flexibility than with mixes sent from the control room, things may not be quite as beneficial as at first sight. The system tends to work very well in small studios where only one or two musicians are recording at any one time. However, with large groups of musicians there are potential risks of the band not playing together if they are all listening to different balances. To highlight this point, consider the case of a foldback system where the drums were fed to four foldback mixer channels; say bass drum, snare, tom-toms and overheads. Dependent upon whichever drum was prominent on any particular foldback mix, the individual musicians may be led to emphasise different beats. During larger recording sessions it is usually the producer or musical director who dictates which beats are to dominate; it is not a question of chance, determined only by an individual musician’s choice of foldback balance. Setting the foldback sets the mood, and it is a particular skill of experienced engineers and producers to be able to use the foldback balance to drive the musicians to play in a desired way. Remember, if the musicians are all going their own ways with the foldback mix, then who is in control of the proceedings? Probably nobody! Quite literally, the musicians may not all be playing to the same beat. In some cases, this is not a problem, but in other cases it could be like an orchestra playing without a conductor and with no agreement as to what to emphasise or where.

It should also be noted that the musicians do not all necessarily know how to make an appropriate foldback mix, especially of a song with which they are not familiar. Foldback balances are really jobs for the engineers and producers to make, with frequent reference to the musicians to confirm their comfort with the balances. A problem with individual mixes is that without the ability for the recording staff to monitor the headphones in the control room, a foldback mix can be living a life of its own, which may or may not be relevant to the producers’ wishes.

Many project studios have begun with a small, individual foldback mixing system on grounds of cost, and have augmented the number of mixers as the studios have grown. Often, the staff of such studios is totally unaware of the constant voltage system because they have never received any professional training. In truth, the different systems have their strengths and weaknesses, and when studios develop there is no reason why they should not offer both the options of local and remote mixing. Many experienced engineers have been appalled when they have gone into a studio and heard the mixes that some musicians were actually trying to work with. Conversely, many musicians have been appalled with what they have been sent from a control room. Getting the foldback balance right is a fundamental necessity for any good recording, so very careful attention should be given to foldback systems, because they form a very important part of the infrastructure of any studio.

Figure 24.3:

In-studio foldback mixing. In this arrangement, single instruments or sub-groups of instruments are fed at line level into the studio. These go to the inputs of a mixer/amplifier matrix which allows each musician, or group of musicians, to set their own foldback mix and overall volume level. The system allows great flexibility in terms of each musician being able to choose an optimum mix, but it needs to be used by musicians who have some skill in mixing, and presumes that they know the score. Its drawbacks are that it splits the concentration of the musicians between mixing and playing, it denies the producer or engineer control over the foldback, and it isolates the engineer from knowing what the musicians are hearing.

Figure 24.4:

In-studio foldback mixing (commercially available alternatives): (a) In this arrangement the stereo input level serves as the output level for each one of the headphones. Effects return level can also be used as a spare stereo input, for a stereo sub-group sent from the control room mixing console; (b) Single output and multi-output headphones amplifiers. Most of these devices come provided with a mono/stereo switch, and some have an alternative stereo input, which may be used both as effects return or as a second foldback mix input.

24.5 Types of Headphones

Where possible, groups of musicians on a common foldback feed should all be using identical headphones. If mixtures of different impedances are used, or mixtures of headphones with different sensitivities, the loudness in all the headsets will not be equal. This is why it is important for the engineer who is monitoring the headphone mix in the control room to be on the same circuit and to use identical headphones whilst making or checking a mix. However, the preferences of musicians towards open or closed headphones are another factor for consideration. Many prefer open headphones, because they feel less cut off from their environment, but there can be situations when their use is inappropriate. Drummers, or other musicians playing loud instruments, may prefer closed headphones. Open headphones provide virtually no isolation from outside noise, so a drummer playing with a kit in a live room, and producing a local 120 dB SPL, will need a potentially ear-damaging level of foldback if using open headphones. On the other hand, headphones with good ear seals may provide 30 dB of isolation, and so from a resulting ambient 90 dB, the drummer could be fed with a mix of instruments which could be heard above the drum level without risk to the ears.

In fact, one must always be careful about the use of excessive level in headphones. The level required in the ear canals for headphones to sound equally as loud as loudspeaker listening can be up to 6 dB higher. This is probably due to the loss of the contribution which the tactile sense and bone conduction provide as augmentation to the ear-canal-only sound, which means that the ear drum could receive four times the acoustic power from headphones than when listening to equally loud loudspeakers. This extra power can cause unexpected ear damage at levels which do not seem to be subjectively too loud. It should therefore be apparent that if a drummer wears open headphones, the levels necessary to overcome the acoustic 120 dB of the drums by an in-ear subjective 125 or 126 dB, would perhaps, in reality, be subjecting the ears to SPLs equivalent to around 130 dB from loudspeakers. This is way over any level which could be considered to be safe. For musicians, whose ears are their tools, the results could be disastrous. To put things into perspective, 130 dB represents over 1000 times the acoustic power to which European industrial workers would be allowed to be exposed, and whose ears are not so necessary for their work.

The above description shows clearly why closed headphones should be used to keep sound out, but vocalists often should wear closed headphones to keep the sound in. The problems can occur when overdubbing vocals. Percussion sounds in the backing track can produce the ubiquitous ‘tizzy tizzy tizz’ that one now hears everywhere from personal stereo systems. If this should leak into the vocal microphone, as it often does, then subsequent processing of the vocal, such as with delays, reverberation or other effects, will also process the overspill. Especially if the vocal is compressed during the mix, the overspill will be brought up in level and the problem will become worse. If a particular vocalist does not like wearing closed headphones it may still be better to work with them, but with one ear-piece partly off the ear, to allow some natural sound in, rather than to run the risk of an undesirable overspill entering the main vocal microphone. ‘Click’ tracks entering vocal microphones via headphones are also a bane.

24.6 Connectors

When the constant voltage type of foldback system is used it is common to provide distribution boxes for the headphones, say with six or eight outlets, at the end of a cable of around 4 or 5 m length which plugs into a wall panel. Outlets can be provided for each foldback channel, either as mono feeds, or stereo pairs, via a simple arrangement of wall sockets, as shown in Figure 24.5. If suitable cable is used, the boxes can be daisy-chained when more outputs from any given feed are needed. Heavy duty microphone cable will usually suffice for such purposes unless the number of headphones being driven from any single cable would be likely to draw more current than the cable could safely handle. If a tracking loudspeaker were to be used, then it would be better to plug it directly into the wall sockets, which should be wired to the power amplifier outputs with good loudspeaker cable.

The use of ‘stereo jacks’ on such circuits is not recommended. XLR type connectors tend to be a better choice. The problem with stereo jacks is that when they are inserted into the sockets they can sometimes short the jack connections together, and a mono jack mistakenly inserted would certainly short circuit the output of one amplifier, leading to possible damage. Jack plugs are better reserved for use with the individual mixer type of foldback systems. In any case, these systems usually benefit from the use of headphones of much lower impedance than the 400 ohms which is normal for the constant voltage distribution systems. The use of different connectors therefore prevents the erroneous connection of headphones of the wrong impedance into either of the systems. This is especially important in situations where both types of system are being used in one studio.

As a further precaution against inadvertent shorting of a power amplifier output, it may be feasible to wire a 15 ohm, 50 watt resistor in series with the feed on the headphone outlet wall panel. With only small numbers of headphones in use, this would cause only a minimal voltage drop. However, with 20 headphones in parallel, yielding 20 ohms in total, the 15 ohm resistor would rob almost half of the power, whilst at the same time restricting the amplifier to only half of its output into 20 ohms. It should also be remembered that under such circumstances the resistor, on music signal, could get very hot as it dissipates around 20 watts of heat. Its siting should therefore be carefully considered. If such a device were to be used for protection of the headphones, then a separate output, perhaps with a ‘Speakon’ connector, could be wired directly to the amplifier for use when a tracking loudspeaker is needed. The pros and cons of these systems need to be individually evaluated for each set of circumstances.

Figure 24.5:

Wall socket arrangement for a constant voltage foldback system. In the above arrangement, the headphones are wired with the –ve of each capsule connected to pin 1 of the XLR; the +ve of the left-hand capsule to pin 2, and the +ve of the right-hand capsule to pin 3. When plugged into the mono outlets (or into distribution boxes plugged into the mono outlets), the two capsules of each headset will be connected together, in parallel, from whichever mono channel of the amplifier they are connected. In the stereo outlet, pins 2 and 3 are connected to different amplifier channels, so the signal in the headphones will appear in stereo.

24.7 Overview

Whatever foldback system may be in use, the importance of providing the musicians with good foldback cannot be over-stressed. Musicians are not instrument-playing robots; they tend to be highly emotional human beings, which is probably why most of them are musicians. Creativity can be nebulous, with moods forming and dissolving on some very subtle bases. It should surely come as no surprise that a musician given a superb, spacious, inspiring foldback mix will probably perform more creatively than a similar musician receiving an ill-balanced mono mix via a pair of headphones of indifferent quality.

Even the tuning of vocals can sometimes be affected by foldback, with the relative loudness of a vocal in a mix being able to drive a vocalist sharp or flat. The feel of a song can also be varied, dependent upon which instruments are emphasised. A prominent snare drum, for instance, will tend to draw the musicians to follow that beat, whereas the emphasis of a hi-hat on an off-beat, with the snare subdued, could pull the track in a different direction. The direction of a recording can be greatly influenced by the choice of foldback instruments and their relative balance, but this can usually only be achieved by a producer or engineer dictating the foldback mix.

Nevertheless, many studio owners and operators are more under the influence of equipment manufacturers and dealers than under the influence of top professional studios and their working practices. The option to mix in the studio is readily supplied by commercially available boxes, which their manufacturers and dealers want to sell. These can be bought, plugged in with suitable leads, and ‘off you go’. On the other hand, the constant-voltage/power-amplifier option is more labour intensive to install, and may not be as easy to assemble with ready-made items. However, for multiple headphone use, this option will certainly be cheaper for the studio, but it is not necessarily in the interests of the equipment dealers to suggest its use.

Of course, when recordings are being made by relatively inexperienced engineers, the reality is that they may not be too skillful in achieving sensitive foldback mixes, and when working alone, without a producer or an assistant, the delegation of the responsibility of foldback mixing to the musicians may be a great relief. What is more, in such circumstances, the musicians may well do a better job of it, so one cannot be too dictatorial here about which system is best. Nonetheless, at least if people are aware that the various possibilities exist then they have some options when selecting what to do when the time comes for expansion. Unfortunately, some mixing consoles do not have sufficient auxiliary outputs to make multiple stereo foldback mixes, so this must also be taken into account when selecting the most appropriate system for any given set of circumstances.

Foldback should never be seen as something of a secondary event in the process of recording; it is crucial. A parallel exists in live sound for concerts. In many countries, the struggle for the prestige of being the front of house (FOH) mixing engineer has left the job of stage monitor mixer being relegated, almost literally, to anybody who did not have another task to perform. In truth, the monitor mixing engineer is more likely to have an effect of the quality of the performance than the FOH engineer, for it is the monitor engineer who sets the conditions under which the band must perform. No band is going to play well with poor monitor mixes, and no front of house engineer is going to make a poor performance sound like a good one. In many instances, the calibre of the monitor engineer is more critical to the overall event than that of the FOH engineer. Stage monitors are foldback, and when considering foldback in terms of stage monitoring, perhaps the relevance of studio foldback mixes is easier to understand. In fact, when major touring artistes are travelling the world, their choice of monitor engineer is usually a matter of considerable importance on their lists of priorities. In many cases, the monitor engineer is almost considered to be like a member of the band. The relationships can be very close, because the artistes understand that the monitor mix can be like a lifeline that can either feed or starve a performance. Such is the power of foldback.

24.8 Summary

For the musicians, the foldback system is their working environment, and it can greatly affect their creativity.

Tracking loudspeakers are sometimes used instead of headphones.

Many recording engineers fail to realise the importance of a good foldback sound for the musicians.

Constant voltage distribution systems allow the use of a great number of headphones, all receiving identical signals and levels, controlled by the recording personnel.

Stereo foldback in headphones greatly eases the task of hearing different instruments in the mix. The spacial separation is a great advantage.

In many studios the musicians can make their own foldback mixes in the studio, but this runs the risk of them not all playing to the same backing track. What is more, the producer has no control over or knowledge about what each musician is listening to. Which system is best will depend on circumstances and the relative experience of the musicians and recordists.

Open and closed headphones each have their advantages and drawbacks. Excessive headphone levels can be ear-damaging, so care must always be taken to avoid the accidental sending of hazardous signal levels.

When different types of foldback systems are in use in one studio, using different impedances of headphones, it is advisable to use different connectors on each type of headphone to prevent damage by accidentally connecting the low impedance headphones into the high voltage circuits.

The use of jack plugs on high voltage circuits is to be avoided.

The importance of a stage monitor mix during a live concert is analogous to the importance of good foldback during a recording.