World domination isn’t my thing, but if it was, I’d be using XML. | ||

| --Norman Walsh | ||

As you undoubtedly know, the World Wide Web has grown in leaps and bounds in the past several years, both in magnitude and in technologies. The fact that people who, only a few short years ago had no interest in computers are now “net junkies”, is a testament to how quickly the Web has infiltrated modern culture. Just as the usefulness and appeal of the Web have grown rapidly, so have the technologies that make the Web possible. It all pretty much started with HTML (HyperText Markup Language), but a long list of acronyms, buzzwords, pipedreams, and even a few killer technologies have since followed. XML (eXtensible Markup Language) is one of the rare technologies that actually progressed from bleeding edge hype to misunderstood buzzword to standard building block. XML has officially arrived, and is used behind the scenes in countless applications and web services. Even so, I’ll leave it to you to decide whether it is truly a killer technology as you progress through this book.

XML’s usage is continuing to grow quickly as both individuals and companies realize its potential. However, in many ways XML is still a relatively new technology, and many people, possibly you, are just now learning what it can do for them. Unlike some other software technologies such as HTML or even Java, XML is a little fuzzier in terms of how it is applied in different scenarios. Just as it’s difficult to look at a person and grasp how their DNA makes them who they are, it can also be challenging to look at an application and get a grasp for how XML fits into the equation. This hour introduces you to XML and gives you some insight as to why it was created and what it can do.

In this hour, you’ll learn

Exactly what XML is

The relationship between XML and HTML

How XML fits into web browsers

How XML is impacting the real world

With the universe expanding, human population increasing at an alarming rate across the globe, and a new boy band created every week, was it really necessary to introduce yet another web technology with yet another cryptic acronym? In the case of XML, the answer is yes. Next to HTML itself, XML is positioned to have the most widespread and long-term ramifications of any web technology to date. The interesting thing about XML is that its impact has gone and will continue to go largely unnoticed by most web users. Unlike HTML, which reveals itself in flashy text and graphics, XML is more of an under-the-hood kind of technology. If HTML is the fire engine red paint and supple leather interior of a sports car, XML is the turbocharged engine and sport suspension. Okay, maybe the sports car analogy is a bit much, but you get the idea that XML’s impact on the Web is hard to see with the naked eye. However, the benefits are directly realized in all kinds of different ways. More specifically, if you’ve ever shopped on Amazon.com, purchased music from Apple iTunes, or read a syndicated news feed via RSS (Really Simple Syndication), you’ve used XML without realizing it.

By the Way

By the way, you might as well get used to seeing loads of acronyms. Virtually every technology associated with XML has its own acronym, so it’s impossible to learn about XML without getting to know a few dozen acronyms. Don’t worry, I’ll break them to you gently!

To understand the need for XML, at least as it applies to the Web, you have to first consider the role of HTML. In the early days of the Internet, some European physicists created HTML by simplifying another markup language known as SGML (Standard Generalized Markup Language). I won’t get into the details of SGML, but let’s just say it was overly complicated, at least for the purpose of sharing scientific documents on the Internet. So, pioneering physicists created a simplified version of SGML called HTML that could be used to create what we now know as web pages. The creation of HTML represented the birth of the World Wide Web—a layer of visual documents that resides on the global network known as the Internet.

HTML was great in its early days because it allowed scientists to share information over the Internet in an efficient and relatively structured manner. It wasn’t until later that HTML started to become an all-encompassing formatting and display language for web pages. It didn’t take long before web browsers caught on and HTML started being used to code more than scientific papers. HTML quickly went from a tidy little markup language for researchers to a full-blown online publishing language. And once it was established that HTML could be jazzed up simply by adding new tags, the creators of web browsers pretty much went crazy by adding lots of nifty features to the language. Although these new features were neat at first, they compromised the simplicity of HTML and introduced lots of inconsistencies when it came to how browsers rendered web pages. HTML had started to resemble a bad remodeling job on a house that really should’ve been left alone.

As with most revolutions, the birth of the Web was very chaotic, and the modifications to HTML reflected that chaos. More recently, a significant effort has been made to reel in the inconsistencies of HTML and to attempt to restore some order to the language. The problem with disorder in HTML is that web browsers have to guess at how a page is to be displayed, which is not a good thing. Ideally, a web page designer should be able to define exactly how a page is to look and have it look the same regardless of what kind of browser or operating system someone is using. This utopia is still off in the future somewhere, but XML is playing a significant role in leading us toward it, and significant progress has been made.

XML is a meta-language, which is a fancy way of saying that it is a language used to create other markup languages. I know this sounds a little strange, but it really just means that XML provides a basic structure and set of rules to which any markup language must adhere. Using XML, you can create a unique markup language to model just about any kind of information, including web page content. Knowing that XML is a language for creating other markup languages, you could create your own version of HTML using XML. You could also create a markup language called VPML (Virtual Pet Markup Language), for example, which you could use to create and manage virtual pets. The point is that XML lays the ground rules for organizing information in a consistent manner, and that information can be anything from web pages to virtual pets.

By the Way

Throughout this book you will learn about several of the more intriguing markup languages that are based on XML. For example, you will find out about SVG and RSS, which allow you to create vector graphics and syndicate news feeds from web sites, respectively.

You might be thinking that virtual pets don’t necessarily have anything to do with the Web, so why mention them? The reason is because XML is not entirely about web pages. In fact, XML in the purest sense really has nothing to do with the Web, and can be used to represent any kind of information on any kind of computer. If you can visualize all the information whizzing around the globe between computers, mobile phones, televisions, and radios, you can start to understand why XML has much broader ramifications than just cleaning up web pages. However, one of the first applications of XML is to restore some order to the Web, which is why I’ve provided an explanation of XML with the Web in mind. Besides, one of the main benefits of XML is the ability to develop XML documents once and then have them viewable on a range of devices, such as desktop computers, handheld computers, mobile phones, and Internet appliances.

One of the really awesome things about XML is that it looks very familiar to anyone who has used HTML to create web pages. Going back to our virtual pet example, check out the following XML code, which reveals what a hypothetical VPML document might look like:

<pets>

<pet name="Maximillian" type="pot bellied pig" age="3">

<friend name="Augustus"/>

<friend name="Nigel"/>

</pet>

<pet name="Augustus" type="goat" age="2">

<friend name="Maximillian"/>

</pet>

<pet name="Nigel" type="chipmunk" age="2">

<friend name="Maximillian"/>

</pet>

</pets>This XML (VPML) code includes three virtual pets: Maximillian the pot-bellied pig, Augustus the goat, and Nigel the chipmunk. If you study the code, you’ll notice that tags are used to describe the virtual pets much as tags are used in HTML code to describe web pages. However, in this example the tags are unique to the VPML language. It’s not too hard to understand the meaning of the code, thanks to the descriptive tags. In fact, an important design parameter of XML was for XML content to always be human-readable. By studying the VPML code for a few seconds, it becomes apparent that Maximillian is friends with both Augustus and Nigel, but Augustus and Nigel aren’t friends with each other. Maybe it’s because they are the same age, or maybe it’s just that Maximillian is a particularly friendly pig. Either way, the code describes several pets along with the relationships between them. This is a good example of the flexibility of the XML language. Keep in mind that you could create a virtual pet application that used VPML to share information with other virtual pet owners.

By the Way

Unlike HTML, which consists of a predefined set of tags such as <head>, <body>, and <p>, XML allows you to create custom markup languages with tags that are unique to a certain type of data, such as virtual pets.

The virtual pet example demonstrates how flexible XML is in solving data structuring problems. Unlike a traditional database, XML data is pure text, which means it can be processed and manipulated very easily, in addition to being readable by people. For example, you can open up any XML document in a text editor such as Windows Notepad (or TextEdit on Macintosh computers) and view or edit the code. The fact that XML is pure text also makes it very easy for applications to transfer data between one another, across networks, and also across different computing platforms such as Windows, Macintosh, and Linux. XML essentially establishes a platform-neutral means of structuring data, which is ideal for networked applications, including web-based applications.

Just as some Americans are apprehensive about the proliferation of spoken languages other than English, some web developers initially feared XML’s role in the future of the Web. Although I’m sure a few HTML purists still exist, is it valid to view XML as posing a risk to the future of HTML? And if you’re currently an HTML expert and have yet to explore XML, will you have to throw all you know out the window and start anew with XML? The answer to both of these questions is a resounding no! In fact, once you fully come to terms with the relationship between XML and HTML, you’ll realize that XML actually complements HTML as a web technology. Perhaps more interesting is the fact that XML is in many ways a parent to HTML, as opposed to a rival sibling—more on this relationship in a moment.

Earlier in the hour I mentioned that the main problem with HTML is that it got somewhat messy and unstructured, resulting in a lot of confusion surrounding the manner in which web browsers render web pages. To better understand XML and its relationship to HTML, you need to know why HTML has gotten messy. HTML was originally designed as a means of sharing written ideas among scientific researchers. I say “written ideas” because there were no graphics or images in the early versions of HTML. So, in its inception, HTML was never intended to support fancy graphics, formatting, or page-layout features. Instead, HTML was intended to focus on the meaning of information, or the content of information. It wasn’t until web browser vendors got excited that HTML was expanded to address the presentation of information. In fact, HTML was in many ways changed to focus entirely on how information appears, which is what ultimately prompted the creation of XML.

You’ll learn throughout this book that one of the main goals of XML is to separate the meaning of information from the presentation of it. There are a variety of reasons why this is a good idea, and they all have to do with improving the organization and structure of information. Although presentation plays an important role in any web site, modern web applications have evolved to become driven by data of very specific types, such as financial transactions. HTML is a very poor markup language for representing such data. With its support for custom markup languages, XML makes it possible to carefully describe data and the relationships between pieces of data. By focusing on content, XML allows you to describe the information in web documents. More importantly, XML makes it possible to precisely describe information that is shuttled across the Net between applications. For example, Amazon.com uses XML to describe products on its site and allow developers to create applications that intelligently analyze and extract information about those products.

By the Way

You might have noticed that I’ve often used the word “document” instead of “page” when referring to XML data. You can no longer think of the web as a bunch of linked pages. Instead, you should think of it as linked documents. Although this may seem like a picky distinction, it reveals a lot about the perception of web content. A page is an inherently visual thing, whereas a document can be anything ranging from a stock quote to a virtual pet to a music CD on Amazon.com.

If XML describes data better than HTML, does it mean that XML is set to upstage HTML as the markup language of choice for the Web? Not exactly. XML is not a replacement for HTML, or even a competitor of HTML. XML’s impact on HTML has to do more with cleaning up HTML than it does with dramatically altering HTML. The best way to compare XML and HTML is to remember that XML establishes a set of strict rules that any markup language must follow. HTML is a relatively unstructured markup language that could benefit from the rules of XML. The natural merger of the two technologies is to make HTML adhere to the rules and structure of XML. To accomplish this merger, a new version of HTML has been formulated that adheres to the stricter rules of XML. The new XML-compliant version of HTML is known as XHTML. You learn a great deal more about XHTML in Hour 21, “Adding Structure to the Web with XHTML.” For now, just understand that one long-term impact XML will have on the Web has to do with cleaning up HTML.

By the Way

Most standardized web technologies, such as HTML and XML, are overseen by the W3C, or the World Wide Web Consortium, which is an organizational body that helps to set standards for the Web. You can learn more about the W3C by visiting its web site at http://www.w3.org/.

XML’s relationship with HTML doesn’t end with XHTML, however. Although XHTML is a great idea that is already making web pages cleaner and more consistent for web browsers to display, we’re a ways off from seeing a Web that consists of cleanly structured XHTML documents (pages). It’s currently still too convenient to take advantage of the freewheeling flexibility of the HTML language. Where XML is making a significant immediate impact on the Web is in web-based applications that must shuttle data across the Internet. XML is an excellent medium for representing data that is transferred back and forth across the Internet as part of a complete web-based application. In this way, XML is used as a behind-the-scenes data transport language, whereas HTML is still used to display traditional web pages to the user. This is evidence that XML and HTML can coexist happily both now and into the future.

One of the stumbling blocks to learning XML is figuring out exactly how to use it. You now understand how XML complements HTML, but you still probably don’t have a good grasp on how XML data is used in a practical scenario. More specifically, you’re probably curious about how to view XML data. Because XML is all about describing the content of information, as opposed to the appearance of information, there is no such thing as a generic XML viewer, at least not in the sense that a web browser is an HTML viewer. In this sense, an “XML viewer” is simply an application that lets you view XML code, which can be a simple text editor or a visual editor that shows how XML data is structured. To view XML code according to its actual meaning, you must use an application that is specially designed to work with a specific XML language. If you think of HTML as an XML language, then a web browser is an application designed specifically to interpret the HTML language and display the results. This is, in fact, exactly what happens when you view an XHTML web page in a browser.

Another way to view XML documents is with style sheets using either XSL (eXtensible Stylesheet Language) or CSS (Cascading Style Sheets). Style sheets have finally reached the mainstream and are established as a better approach to formatting web pages than many of the outdated HTML presentation tags. Style sheets work in conjunction with HTML code to describe in more detail how HTML data is to be displayed in a web browser. Style sheets play a similar role when used with XML. Most modern web browsers (Internet Explorer, Firefox, Opera, Safari, and so on) support CSS, as well as providing some level of support for XSL. You learn a great deal more about style sheets in Part III, “Formatting and Displaying XML Documents.”

By the Way

In addition to popular commercial web browsers, the W3C offers its own open source web browser that can be used to browse XML documents. The Amaya web browser supports the editing of web documents and also serves as a decent browser. However, Amaya is intended more as a means of testing XML documents than as a commercially viable web browser. You can download Amaya for free from the W3C web site at http://www.w3c.org/Amaya/.

In addition to style sheets, there is another important XML-related technology that is supported in major web browsers. I’m referring to the DOM (Document Object Model), which allows you to use a scripting language such as JavaScript to programmatically access the data in an XML document. The DOM makes it possible to create web pages that intelligently access and display XML data based upon scripting code. You learn how to access XML documents using JavaScript and the DOM in Hour 16, “Parsing XML with DOM.”

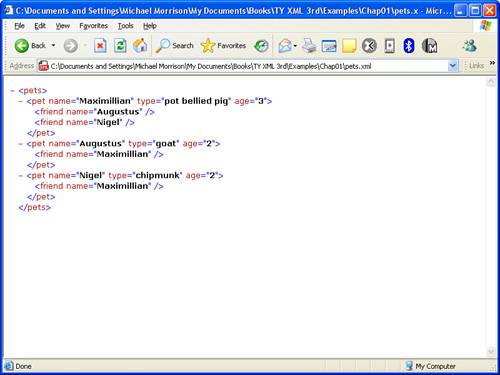

One last point to make in regard to viewing XML with web browsers is that some browsers allow you to view XML code directly. This is a neat feature because it automatically highlights the code so that the tags and data are easy to see and understand. Additionally, an XML document is usually displayed as a hierarchical tree that allows you to expand and collapse sections of the data just as you expand and collapse folders in a file manager such as Windows Explorer. This hierarchical user interface reveals the tree-like structure of XML documents. Figure 1.1 shows the virtual pets XML document as viewed in Internet Explorer.

Figure 1.1. You can view the code for an XML document by opening the document in a web browser that supports XML, such as Internet Explorer.

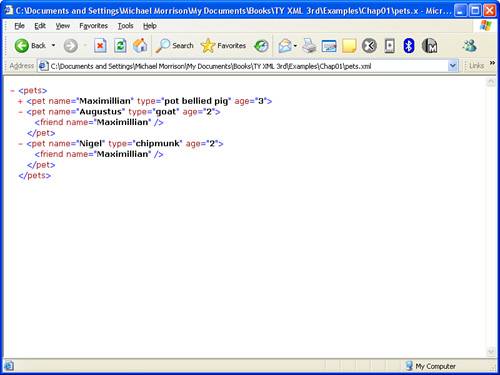

Although this black and white figure doesn’t reveal it, Internet Explorer actually uses color to help distinguish the different pieces of information in the document. To expand or collapse a section in the document, just click anywhere on the tag. Figure 1.2 shows the document with the first pet element (Maximillian) collapsed; notice that the minus sign changes to a plus sign (+) to indicate that the element can be expanded.

Figure 1.2. In addition to highlighting XML code for easier viewing, XML-supported web browsers make it possible to expand and collapse sections of a document.

Keep in mind that the web browser in this case is only showing the XML document as a tree of data because it doesn’t know anything else about how to render it. You can provide a style sheet that lays out the specifics of how the data is to be formatted and displayed, and the browser will carefully format the data instead of displaying it as a tree. You will tackle this topic in Part III. This approach is commonly used to style XML data for viewing on the Web. Even so, it can be handy opening an XML document in a browser without any styling applied (as shown in Figures 1.1 and 1.2) and studying it as a tree of data. Although browsers provide a neat approach to viewing XML code in a tree-like structure, you’ll probably rely on an XML editor to view most of the XML code that you develop. Or you can use a simple text editor such as Windows Notepad. You learn about XML editors in the next hour, “Creating XML Documents.”

Hopefully by now you understand some of the reasons XML came into being, as well as how it will likely fit in with HTML as the future of the web unfolds. What I haven’t explained yet is how XML is impacting the real world with new markup languages. Fortunately, a lot of work has been done to make XML a technology that you can put to work immediately, and there are numerous XML-related technologies that are being introduced as I write this. Following is a list of some of the major XML-based languages that are supported either on the web or in major XML-based applications, along with the kinds of information they represent:

WML (Wireless Markup Language)— Web pages for mobile devices

OFX (Open Financial Exchange)— Financial information (electronic funds transfer, for example)

RDF (Resource Description Framework)— Descriptions of information in web pages

RSS (Really Simple Syndication)— Syndicated web site updates (news feeds and blog entries, for example)

MathML (Mathematical Markup Language)— Mathematical symbols and formulas

OeB (Open eBook)— Electronic books

OpenDocument— Open file format for office applications (word processing, spreadsheet, and so on)

OWL (Web Ontology Language)— Semantic web pages (an extension of RDF)

P3P (Platform for Privacy Preferences)— Web privacy policies

SOAP (originally Simple Object Access Protocol)— Distributed application communication

SVG (Scalable Vector Graphics)— Vector graphics

SMIL (Synchronized Multimedia Integration Language)— Multimedia presentations

UDDI (Universal Description, Discovery, and Integration)— Business registries

WSDL (Web Services Description Language)— Web services

XAML (eXtensible Application Markup Language)— Graphical user interfaces (used by Microsoft in the new version of Windows, codenamed Longhorn)

XBRL (eXtensible Business Reporting Language)— Business and financial data

I told you earlier that XML people love acronyms! And as the brief descriptions of each language suggest, these XML languages are as varied as their acronyms. A few of these languages are supported in the latest web browsers, and the remaining languages have special applications that can be used to create and share data in each respective format. To give you an idea regarding how these languages are impacting the real world, consider the fact that the next major release of the Windows operating system, codenamed Longhorn, is using XAML (pronounced “zammel”) throughout to describe its user interfaces in XML. Additionally, Microsoft and Intuit have invested heavily in OFX (Open Financial eXchange) as the future of electronic financial transactions. OFX is already supported by more than 2,000 banks and brokerages, in addition to payroll-processing companies. In other words, your paycheck may already depend on XML!

By the Way

Another interesting usage of an XML language is SVG, which is used to code plats for real estate. A plat is an overhead map that shows how property is divided. Plats play an important role in determining divisions of land for ownership (and taxation) purposes and comprise the tax maps that are managed by the property tax assessor’s office in each county in the U.S. SVG is actually much more broad than just real estate plats and allows you to create virtually any vector graphics in XML. You learn more about SVG in Hour 6, “Using SVG to Draw Scalable Graphics.”

I could go on and on about how different XML languages are infiltrating the real world, but I think you get the idea. You’ll get to know several of the languages listed throughout the remainder of the book. More specifically, Hour 23, “Going Wireless with WML and XHTML Mobile,” shows you how to code web pages for mobile devices, while Hour 24, “Syndicating the Web with News Feeds via RSS,” shows you how to use the RSS language to efficiently stay up to date with your favorite web sites.

Although it doesn’t solve all of the world’s problems, XML has a lot to offer the web community and the computing world as a whole. Not only does XML represent a path toward a cleaner and more structured HTML, it also serves as an excellent means of transporting data in a consistent format that is readily accessible across networks and different computing platforms. A variety of different XML-based languages are available for storing different kinds of information, ranging from financial transactions to mathematical equations to multimedia presentations.

This hour introduced you to XML and helped to explain how it came to be as well as how it fits into the future of the Web. You also learned that XML has considerable value beyond its impact on HTML. This hour, although admittedly not very hands on, has given you enough knowledge of XML to allow you to hit the ground running and begin creating your own XML documents in the next hour.

The Workshop is designed to help you anticipate possible questions, review what you’ve learned, and begin learning how to put your knowledge into practice.

When XML is referred to as a meta-language, it means that XML is a language used to create other markup languages. Similar to a meta-language is metadata, which is data that is used to describe other data. XML relies heavily on metadata to add meaning to the content in XML documents. RDF and OWL are examples of XML vocabularies that expand on the concept of metadata by attempting to add meaning to web pages. | |

XHTML is the XML-compliant version of HTML, which you will learn about in Hour 21. | |

Most standardized web technologies, such as HTML and XML, are overseen by the World Wide Web Consortium, or W3C, which is an organizational body that helps to set standards for the Web. |

1. | Consider how you might construct a custom markup language for data of your own. Do you have a collection of movie posters you’d like to store in XML, or how about your Wiffle ball team’s stats? What kind of custom tags would you use to code this data? |

2. | Visit the W3C Web site at http://www.w3.org/ and browse around to get a feel for the different web technologies overseen by the W3C. |