Tools for Better Understanding

There are many books on personal interaction and tough conversations. There’s no way to fully cover this topic here. There are a few things I’d like to mention, though, as I’ve found them useful in these sorts of situations. Think of these topics as starting points.

What about When the Other Person Is Being Unreasonable?

You cannot change another person. You can only choose your own behavior; that’s hard enough. So what can you do when faced with someone who is acting badly toward you?

Realize, first of all, that you do not have to stay. I don’t say this lightly. There may be many advantages to staying in that organization or situation, and many disadvantages to leaving. It may be very costly to give up that job and very difficult to find another. These trade-offs vary with the situation and the person. I’m not recommending that you leave, but I am recommending that you realize that’s a possibility. You are not a prisoner, even if it might feel like it. You can find a way to go somewhere better if you put your mind to it. Knowing that can help you cope with staying.

And while you cannot change another person’s behavior, you can choose how you cope with it. A congruent coping stance will help minimize the damage to yourself, and provide the most options for how you choose to behave. When you’re balanced, you can better recognize the unmet needs that the other person cannot articulate, especially the personal needs. When you’re balanced, you’re prepared to respond in many directions, without giving up your self-esteem.

What about When You React out of Habit?

As I said, incongruent coping stances are often longstanding habits first formed in early childhood. You will revert to them from time to time. When you do, try to figure out what triggered you to take that stance. In my experience, it’s usually a conversation gone wrong.

There’s a lot that goes on in a conversation, and most of it isn’t visible from the outside. We process what we hear through a lot of filters before we give our response. Much of that processing is based on past experience more than current events. There are many places and ways that it can go astray. And it all takes place in the blink of an eye, or perhaps faster than that, for every part of the conversation.

Ingredients of an Interaction

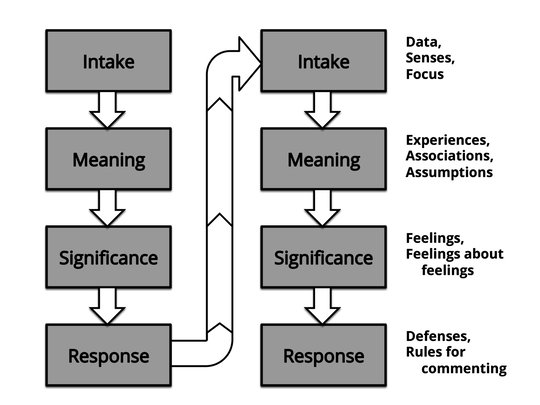

All of this activity is described in another of Virginia Satir’s models of human behavior. This one is called the Ingredients of an Interaction. Let’s walk through an example to see how it works.

We start with actual data. Light enters our eyes and is focused on our retinas. Oscillating air molecules beat on our eardrums and get transmitted to our inner ear. Chemicals in the air find receptors in our nose. All of these things generate nerve signals that go to our brain. This sensory input is as close to raw data as we can get.

Roy and Kelly are having a conversation at the whiteboard. They don’t notice as Lou walks up to them and holds out some papers to Roy. Roy stops in mid-sentence as Lou says, “Could you estimate this feature for the September release?” As Roy is reaching for the papers, a whole lot of things are already going on.

Intake

As part of the sensory intake, Roy heard “Would you estimate this feature for September release?” Note that this isn’t quite what Lou said, but it’s pretty close. Roy had been preoccupied with his conversation with Kelly, and wasn’t primed for careful listening. Still, he got the gist of it.

He also saw that the sheaf of papers was fairly thick, and stapled together. As he took the papers, he looked up and noticed that Lou was looking down at the papers and wasn’t looking him in the eye.

There are other things that Roy could have noticed, such as the fact that Lou was wearing a blue-striped, button-down shirt, and there was a slight aroma of cigarette smoke in the air. These facts were filtered out before Roy was aware of them, common enough to be unremarkable.

Roy also didn’t notice that Lou had paused for a moment before saying anything. During that time Lou was looking directly at Roy, but that went unobserved. Roy didn’t notice that Lou was there until he started to speak.

Intake depends not just on what is happening, but how we focus our attention. There’s a lot of stuff we don’t notice because we’re focused on something else, or because it seems unremarkable. Even when we’re paying attention to something, we might not be completely focused and might not get it right. Our eyes and ears can get fooled.

We’ve already lumped some basic meaning into the intake description. We’ve converted sounds into words, and light waves into recognizable objects. That’s the level of data that is convenient to describe, but there could be errors in that interpretation. We saw an example of that when Lou said “could” and Roy heard “would.”

Meaning

Making meaning of the data goes much deeper than this, though. Roy looked at the sheaf of paper and presumed that, since they’d written down the description of what they wanted in the feature, he was not going to get to interact with the business people asking for it. Therefore, he was not going to be able to negotiate the scope.

We make meaning of what we sense based on our past history and experience. Who does this person remind me of? When has this, some part of this, or something like some part of this happened in the past? The association may be a minor part of the sensory intake. What has happened in similar situations in the past?

That scope wasn’t negotiable was an assumption based on past experience, but the truth is that he’d never tried to negotiate the scope of written requirements since coming to work for Riffle & Sort. He’d tried it once when he worked at Empire Enterprises and it hadn’t worked out well. Not only did it waste a lot of his time, but the business people weren’t interested in negotiating and told his boss that he wasn’t a team player. He hadn’t tried again since that happened.

With that assumption, Roy further assumed that he was being directed to find a way to fit everything in the requirements document into the software by September. He didn’t stop to consider other possibilities. It could be that…

- Lou wanted to know if it might be possible to do it all by September,

- Lou wanted to know what might be possible to do by September, or

- Lou wanted confirmation that the request was not feasible.

I’m sure you can think of other possibilities. Roy’s mind, however, raced on. “Since Lou wouldn’t look at me, it’s surely going to be a death march.” Since Roy hadn’t noticed Lou earlier, he hadn’t seen Lou looking at him directly. Without that data, to him, it hadn’t happened. Roy attributed it to Lou’s feeling about the project and their relationship rather than to the moment in time when Roy noticed Lou’s presence.

While we, at our leisurely pace, can notice some likely and possible discrepancies in meaning, Roy’s brain is still charging ahead at full speed. It grabs the first meaning it makes of the data and plows full speed ahead into the significance of that meaning.

Significance

At first, Roy felt annoyed at being interrupted in his conversation with Kelly. As he comprehended the meaning of the interruption—as he interpreted it—he felt a dread of getting into trouble, one way or another. It might be for not estimating accurately, for not getting the work done, for misinterpreting the requirements, or for myriad other things that could happen. He felt stuck in a bad position.

He didn’t like feeling stuck. It made him angry to feel this way, yet again. His heart beat faster and he felt a bit jittery. His blood vessels dilated and his face turned red. He could feel the heat radiating from his face.

From our uninvolved viewpoint, we can notice that the significance of an event, from a personal point of view, is related to how it makes us feel—and to how that feeling makes us feel. In the software development field, many people value rationality over emotion, or may even want to deny the existence of emotion. This doesn’t make emotions go away. In fact, it illustrates the emotional aspects of the human animal. We operate by both emotions and rationality, but if one is primary, it’s surely the emotions.

From Roy’s point of view, this is likely the first point in the process where he becomes aware of his reaction. Everything has happened so fast that it’s hardly noticeable. The physiological changes from an emotional change got his attention. His response is likely more about his feeling of the significance than it is about the trigger.

Response

When we respond, we go through a couple more filters. One is the ego defense, which helps us maintain our sense of self. In this story, Roy thinks “Lou doesn’t like me.” In reality, this is probably a projection of Roy’s anger and dislike onto Lou. Rather than being Lou’s actual emotions, Roy assigns them to Lou.

But Lou is obviously above Roy in the power hierarchy of the organization. Roy doesn’t feel comfortable speaking freely and openly to him, especially when he’s upset with Lou. Effectively, Roy has a commenting rule that says “I can’t express negative feelings to my boss.”

Finally, we reach an observable outcome. Roy says, “Sure thing, boss.” These words were spoken in a flat tone with tight lips and accompanied by steely narrowed eyes. And, of course, there is the flushed face. The visible signs are not congruent with the words, and this mismatch may also be noticed.

These observable responses, if noticed, become part of the intake for Lou. Lou will also interpret his sensory perceptions through the lens of his past experience and history, will attach significance based on feelings and the secondary feelings about the primary feelings, and then respond according to his defenses and rules for commenting. Back and forth it goes following the same complicated but very fast processing by each participant.

Most of the time, we are not aware of all the steps we go through. If we remain unaware, we cannot choose our behavior. Our patterns choose it for us, and we usually get similar results. Awareness is the key to opening up conscious choices in how we respond.

Changing for the Better

Changing our behavior is hard and, especially at first, feels uncomfortable and disorienting. That makes us want to retreat to the familiarity of how we’ve been. If we stick to it, we reach an “aha” moment where it starts to make sense. From there, it’s mostly a matter of practice to assimilate the change in our “new normal.”

Not changing leaves you stuck in the place where you’ve been. Picture that “better situation” surrounding estimation again. See yourself shoulder to shoulder with your counterpart, looking out for the needs of the organization. Imagine them paying attention to your needs and working to understand you. That won’t happen without your doing the same with them. Notice them hearing your concerns and what you have to say. That starts with your listening to their concerns.