Understanding Human Behavior

Since better estimates won’t fix the relationships between people, let’s look at some models of these relationships from the fields of psychology and social work. This will give you some background understanding to help you identify and address the issues.

Congruence

Congruence is a term that psychologist Carl Rogers borrowed from geometry to describe the alignment of different aspects of a person, including what they think and feel, the affect they present, and how they behave with others. This is often expressed as a person’s image of who they are today being aligned with their image of their ideal self, even if not fully realized.

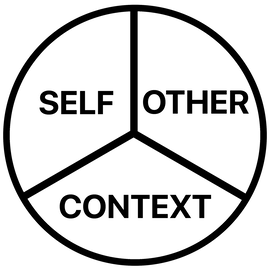

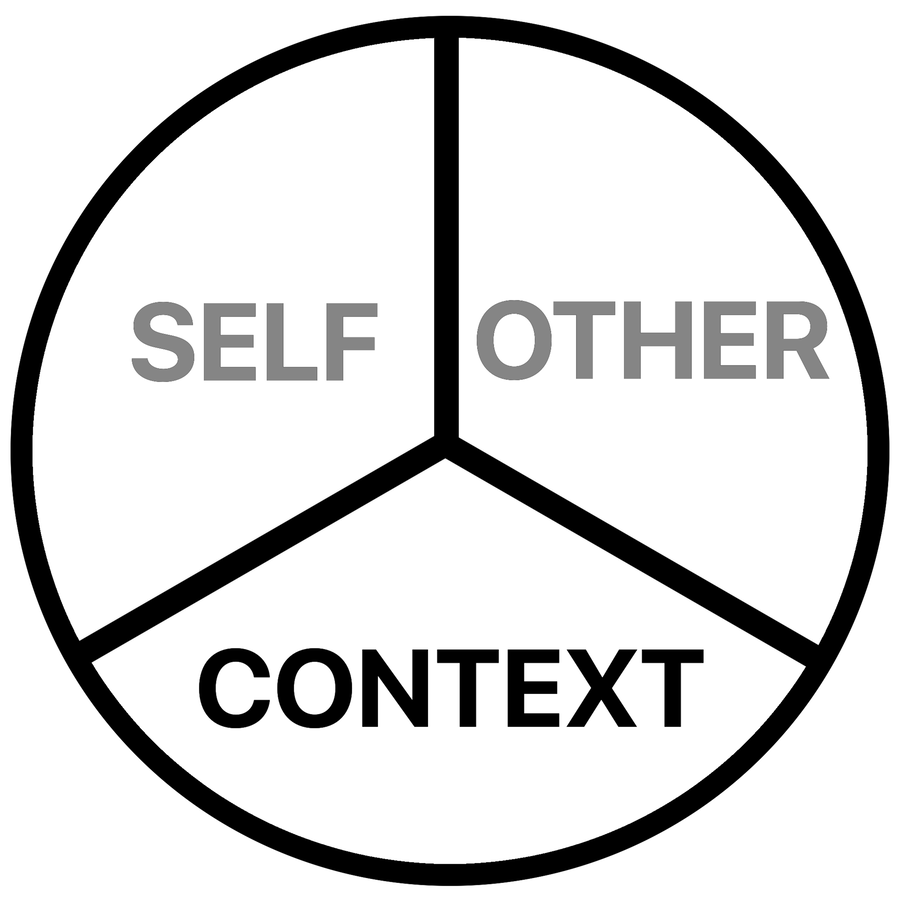

Building on this idea, Virginia Satir, a social worker and family therapist who also worked with Jerry Weinberg to apply her ideas to business situations, described achieving congruence as balancing the needs of yourself, the other with whom you’re interacting, and the context of the situation.

This balance of concerns allows us to be genuine, and have our outward affect match our inner self. When we are concerned about possible risk, our actions show this concern rather than a false appearance of devil-may-care. When we are happy at achieving some goal, it shows on our face and in our posture. You might think that this is a risky thing to do, tipping your hand to others and making yourself vulnerable in the situation. If you were only reflecting your own thoughts, emotions, and needs, then you might be right. When you’re considering theirs and yours, plus the situation at hand, then this transparency becomes a benefit to the situation and current interaction.

Congruence, as described by Virginia Satir, goes further than “the inside matches the outside.” It also includes attuning the inside with what’s happening around you—not just the physical happenings, but what’s happening with the people around you. Understanding that requires some empathy for those people.

Empathy

Empathy is the ability to see and feel the world as others do, from their point of view. This is different from sympathy, which allows you to have compassion for their situation as seen from your own point of view.

There is a cognitive aspect to empathy, which allows you to understand the other’s worldview and goals. This aspect clues you into what makes sense to them, and why it does so. There is also an emotional aspect, which allows you to understand how their situation feels to them. Again, this is from their point of view, not how it would feel to you if you were in their position.

Together, these aspects help you understand the other person’s rational and emotional needs, as they understand and feel them. Such understanding is important if you’re to keep their needs in mind during an interaction. This does not obligate you to agree with them. Their thoughts, feelings, and viewpoint are, however, a fact. They exist. Ignoring them blinds you to a part of the world that is important to this particular interaction with them.

Some people worry that “too much empathy,” especially the emotional aspect, will be overwhelming and lead to making poor decisions. Rather than a problem with the amount of concern, this indicates being out of balance, and paying insufficient attention to the needs of yourself. Likewise, the congruent attention to the needs of the context will balance out cognitive aspect of empathy. This avoids the situation where you give the other whatever they demand.

Let’s take a look at the various directions that these concerns can get out of balance. That way you can recognize the lack of balance more readily, and more easily figure out where to restore the balance.

Coping Stances

When we’re facing a difficult situation, we generally fall back on habitual patterns of coping. When we are born, we know nothing about how to survive in the confusing and scary world into which we have suddenly found ourselves. As we interact with our environment and the people around us, we start learning that some behaviors “seem to work,” and we therefore tend to repeat them in other situations. As we learn and grow, we acquire more and more sophisticated responses to our world, but retain a base of the patterns we learned as babies and toddlers. So, when problems arise, such as:

- Needing to ask for an estimate from someone who doesn’t trust you

- Being asked for an estimate by someone you don’t trust

- Receiving an estimate that doesn’t match your desires or expectations

- An estimate given for one set of assumptions that gets used for something else

how do you respond? If you’re like most people, you respond in a fashion that’s like the way you’ve responded before. You follow familiar patterns of dealing with an emotionally volatile problem. And the other person does likewise. This leads to the patterns of bad behavior that are so well-known in our industry.

As Virginia Satir often said, “The problem is not the problem. The problem is the coping with the problem.” How we react to problems affects us more than the problem itself, and that’s especially true in problems of human communication.

When we fail to balance the trio of needs, we fall into less effective coping stances. We each tend toward a certain off-balance stance. We habitually respond in particular ways when something goes wrong. Some of these habits we learned very early in life and have reinforced them ever since.

Let’s take a quick look at the coping stances identified by Virginia Satir. You can find more detail on these in many of Satir’s books, including Making Contact [Sat76], Helping Families to Change [SST76], The New Peoplemaking [Sat88], and The Satir Model [SGGB06], among others.

Blaming Stance

When something you’re involved with goes badly, what is your reaction? One common reaction is to declare that it’s not your fault. And if it’s not your fault, the next assumption is that it’s someone else’s fault. If we point out the person whose fault it is, that surely clears us.

“The project missed the release deadline because the development team gave me an optimistic estimate.”

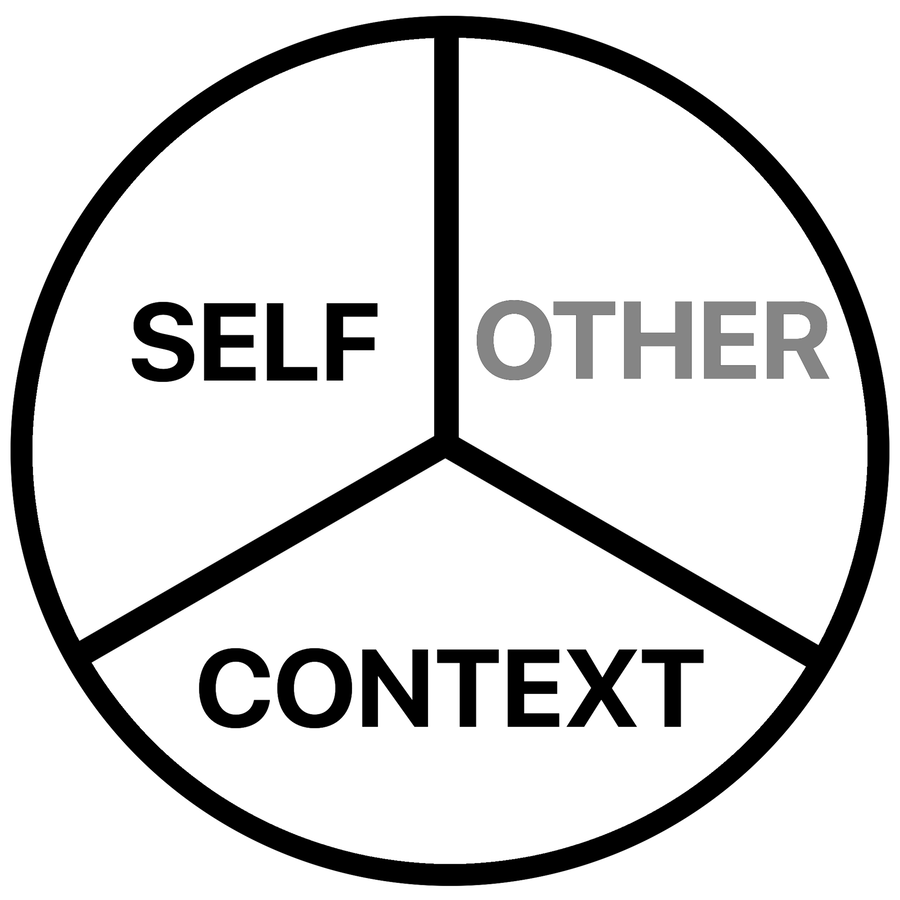

This implies, “there’s nothing I could do about it. They made the mistake.” Blaming works by neglecting the needs of the “other” person. Doing so magnifies the attention to our own needs at the expense of theirs. “I am important and you are not.” This leads to much of the unhappiness around estimation. Someone in the scene is blaming someone else.

If that person blames back, you may get a shouting match. You may have noticed this if you’ve seen someone respond to a request for an estimate with a refusal.

“They shouldn’t have believed the estimate. It was made when we knew the least about the project. In fact, they shouldn’t ask us for estimates at all. You don’t need an estimate to create software. It will get done when it gets done.”

We all hate to get blamed for something, especially when we feel it’s outside our control. It’s common to duck blame by shifting it to someone else. You might be on the blaming side or the receiving side of this situation. The truth in difficult situations is that the result is due to a combination of influences, including the behavior of all of the people involved.

If you find yourself blaming others, take some time to explore their needs. You don’t have to agree that their needs are more important. Just being aware of them will help you negotiate the conflict.

Placating Stance

When someone is blaming you, an obvious stance to quiet things down is to give in, no matter what.

“I’d better give them exactly what they ask for, or else they’ll blame me.”

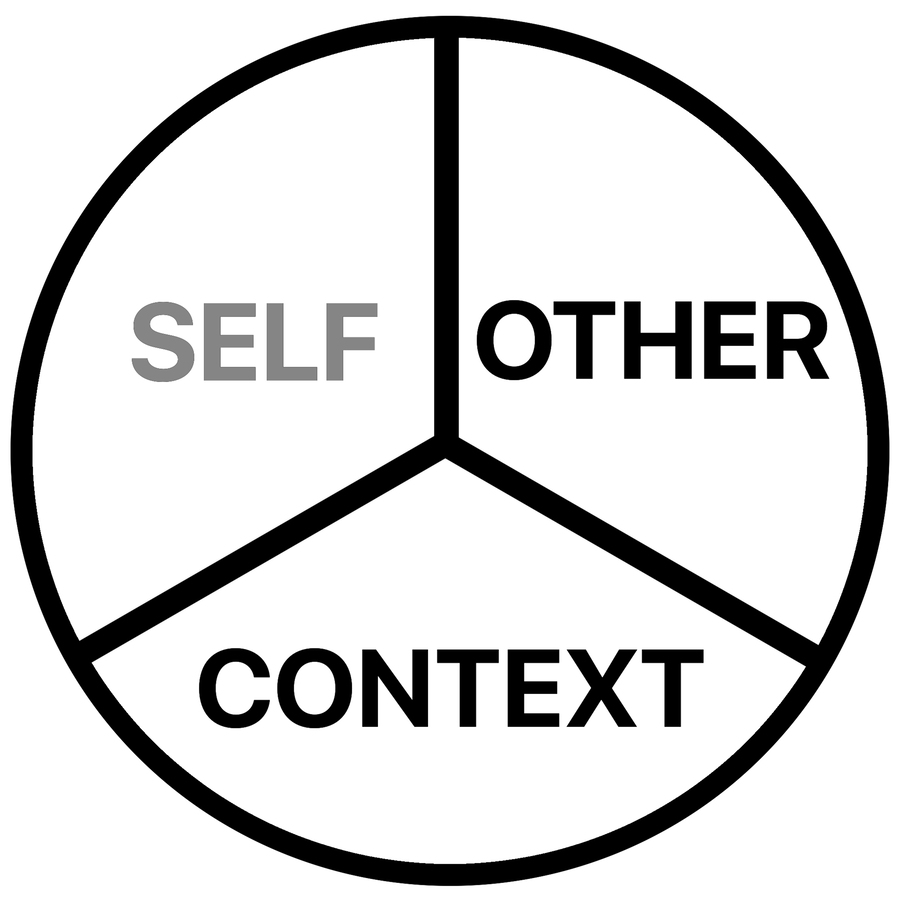

This is the placating stance—neglecting your own needs in deference to the other person’s. It may be quieter but it’s no better at solving your or the organization’s problems. And it can leave you feeling like you’ve been blamed whether or not the other person has done so.

Some people are skilled at manipulating the empathetic people around them to get what they want. They play to the sense of empathy and compassion, heightening the emotional aspect of empathy to the point it obscures the sense of self. This, also, is a placating stance. It doesn’t matter whether you’re denying your own needs out of fear or compassion; if you neglect yourself, you will lose the balance of congruence.

The blaming and placating stances reinforce each other well. They’re like bookends of dysfunction.

If you find yourself “giving in” frequently, and especially if you do so in anticipation of what hasn’t happened yet, consider what needs of your own you might be neglecting. And think of how you can assert those needs in a neutral, nonconfrontational way.

Super-Reasonable Stance

Another coping stance is to focus just on the context, trying to take a cold, impersonal view. This ignores the people along with their needs and emotions. There is no a priori need for estimation, however. We estimate to meet the needs of people trying to make their business or other organization successful.

“The work is going to take exactly some amount of time. Our job is to calculate that precisely and accurately.”

You would think that would take care of the organizational problems, but that’s not the way that organizations composed of people work. This response ignores the human emotions of uncertainty. If you don’t handle the needs of the people, the organization also doesn’t work well. You cannot deal effectively with risk without acknowledging that uncertainty.

Also, it’s my experience that the super-reasonable stance often isn’t as neutral as it’s made out to be.

“It’s going to take however long it takes. Estimates don’t change that.”

This statement is tautologically true, but pointedly ignores the needs of the person wanting the estimate, while infringing little on the needs of the person on the hook for providing the estimate and the software. A different expression of the needs of the context might imply the opposite.

“It’s going to ship on August 15. Difficulties in development don’t change that.”

This expression obviously ignores the needs and worries of the development team, but it also might bother the product manager who wants to ship on an announced date but also include promised functionality that works correctly and doesn’t embarrass the company.

If you find yourself avoiding the personalities involved, then remember that humans run on emotions as well as thought. Spend some time learning how to get in touch with your feelings and recognize the feelings of others.

Irrelevant Stance

The irrelevant coping stance ignores all the needs. You may recognize this stance by remembering the class clown in school. It has made a resurgence in software development as a meme that is sometimes phrased as “no cares given.”

When adopting the irrelevant stance, a person gives up on the situation altogether. They quit trying to meet the needs of any person or the organization. They build a shell to protect themselves, and present that shell to the world instead of their needs and feelings. This serves as a distraction from the uncomfortable situation. As you can guess, this doesn’t help solve the problems, either.

If you find yourself playing the role of joker in tense situations, consider how you can more often address the issues and feelings at hand, rather than obscuring them.

You’ve probably noticed the three sets of needs, which may be acknowledged or ignored, results in 2^3 or eight possible combinations. Of these possibilities, blaming, placating, super-reasonable, and irrelevant are the four most common coping stances, not just of software development organizations, but of people. They’re called incongruent because the externally visible affect doesn’t match the internal feelings, beliefs, expectations, and yearnings. This dissonance between the internal self and the external self is uncomfortable, though people may hang tightly to it because they’re familiar with it. The incongruence between internal and external reliably gets in the way of solving the actual problems. It leaves us fighting battles that no one wins.

Congruent Stance

To do our best work, we’d like to maintain a congruent stance: one where our internal feelings match our outward actions; one where we balance our attention on our needs, the needs of others, and the needs of the context in which we’re operating.

This allows us to make the best decisions we are capable of making, given our skills and knowledge. Balancing these three viewpoints, we come closest to a rational view of the situation. We can see the conflicts between needs and make informed trade-offs based on our core values. Our external actions truly harmonize with our internal thoughts, feelings, and values.

This is not an easy balance to maintain. In fact, it’s impossible for mere mortals to stay in perfect balance, respecting the needs of our self, the other, and the context, all the time. Events and emotions push us around and knock us off-balance. It’s a dynamic balance; it’s not something we can do once and then relax. We may be thrown off our balance, but with practice we can notice this and return to that balance point.

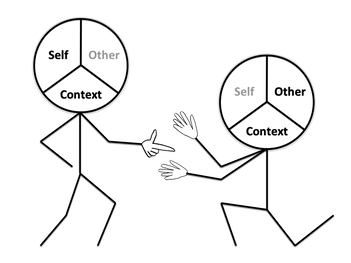

While we can learn to control our own behavior, we cannot control the behavior of those around us. If someone is blaming us, we cannot make them stop. What can we do?

If you can cope congruently, it will immediately help. When you realize that the blaming behavior of the other person is a result of their incongruent coping, then it takes some of the sting out of it. Even if you did something that, in retrospect, you would do differently if you had it to do over, attending to your own needs includes realizing that you, like all people, make mistakes. Admitting this without defensiveness, and also attending to the needs of the blamer and the situation, will go a long way toward a better resolution.

Paying attention to the needs of others, both the ones related to your common context and those they personally perceive, will give you clues that may help. With this starting point, look back to the Rule of Three and explore potential ways to improve the situation.

What would that better situation look like? Let’s explore some possibilities together.