4. Of Rights and Wrongs

In the United States, as a creator of artistic works—your photos in this case—you have the legal right to control how your photos are used for a limited period of time (your lifetime plus 70 years). This right is what is known as copyright, and it is the same right extended to authors, composers, playwrights, and other artists creating new works that are fixed in some tangible form. Assuming you are not working on someone else’s time or dime (in a work-for-hire situation), the moment you create a photo you own the copyright to that work. When you make your photos available on a stock site, you are saying that you are willing to let others use your creative work in exchange for a licensing fee. That is the foundation upon which this whole stock concept operates.

When it comes to licensing your photos as royalty-free stock, you also need to be cognizant of the copyrights of other artists, the rights of the people who may be visible in your photos, and the concerns of individuals and companies whose trademarks or other properties may appear in your photos. I’m not a lawyer and do not intend to give legal advice (always seek a trained professional when you want legal advice). This chapter is simply a roadmap for avoiding rejections due to rights problems, so you can focus your energy on the more fun and revenue-generating parts of the process.

The legal issues that relate to what subjects can be used in commercial stock photography can be a source of frustration to many contributors because the clear examples of what you can and cannot use tend to reside at the extreme ends of the spectrum. This leaves a wide area of gray in the middle that is open to interpretation and which can be heavily influenced by the unique context of any given photo. Over the years I have seen microstock agencies steadily become more risk-averse, meaning they are less willing to accept images that are potentially problematic for their customers to use in commercial projects, that is, unless the contributors are able to secure specific permissions in the form of releases of liability from the people or property owners of the items used as subjects in the images.

Figure 4.1. Justice Scale and Gavel. © istockphoto.com/DNY59

The key point to keep in mind when creating royalty-free stock is that you are producing images for other people to use in a wide range of projects. The potential uses of the images is what drives the acceptance guidelines at various microstock sites, and it is those guidelines that I want to help you navigate. The best place to start is by understanding exactly what types of uses are granted to the people who buy the licenses.

Reading the Fine Print

As you consider the idea of submitting your work to any stock site, I suggest you start by reading the terms of the site’s license that spells out how your photos can be used. Every site will have its content license posted somewhere along the path a customer takes between opening the wallet and downloading a photo. The content license is typically found linked off the same page the photos are displayed, but it may also be in a section of the site devoted to its legal documentation.

No two licenses are worded exactly the same, so take the time to read each site’s license carefully. If you find there are uses allowed that you don’t agree with, then do not submit your work to that site. For example, perhaps you do not want to see images of your son or daughter used in any advertising, or perhaps you have a person in mind for modeling who doesn’t mind advertising uses as long as they can choose the product. If you want more control—and there is nothing wrong with that since this is your intellectual property—then you should pursue other avenues for licensing your work. People who do contribute to microstock sites have decided they have some images they don’t mind being used in the ways outlined in the license. The choice is entirely yours to make. Just go in with both eyes open so that you know what you are allowing people to do with your photos before you submit them.

Permitted Uses

Licensing documents can take a little time to read and digest. It is important, though, to read them in full to get the complete picture. I want to highlight the permitted uses sub-section from iStockphoto to give you an idea of the range of uses that are covered (every site has its own version of these uses, so read each carefully). The following are “Permitted Uses” of content:

• Advertising and promotional projects, including printed materials, product packaging, presentations, film and video presentations, commercials, catalogues, brochures, promotional greeting cards and promotional postcards (i.e., not for resale or license);

• Entertainment applications such as books and book covers, magazines, newspapers, editorials, newsletters, and video, broadcast and theatrical presentations;

• On–line or electronic publications, including web pages to a maximum of 800 × 600 pixels for image or illustration content or to a maximum of 640 × 480 for video content;

• Prints, posters (i.e., a hardcopy) and other reproductions for personal use or promotional purposes specified in (1) above, but not for resale, license or other distribution; and… (This is just a portion of the document. You can read the complete document at www.istockphoto.com/license.php.)

These uses are where the rubber meets the road, and this is what drives the creation of each site’s rules and guidelines for submission. In a nutshell, because such a wide range of uses are permitted in a standard license, each site is only going to accept content that can safely be used in any of those scenarios without causing legal problems for their customers.

Ultimately, it is the responsibility of the end user—the person paying for the license—to ensure that they have the proper permissions to use the content before they publish. But it doesn’t make any sense from the stock site’s point of view to provide customers with content that they might not be able to get permission to use. The most effective way for a site to provide useful content to its customers is to enforce relatively conservative submission guidelines so that riskier and potentially more problematic content is kept off the site completely.

In the last few years, an increasing number of microstock sites have begun to offer their customers an editorial-only royalty-free license, which is a more restrictive version of their standard commercial royalty-free license, in an attempt to enter the market for licensing content in specific ways that do not require having releases of liability from the subjects in the images.

Editorial Options

What makes the editorial option different is that it doesn’t allow for any advertising or promotional uses of the images. The allowed uses are always the key. There are situations—such as news reporting and academic works—that don’t require model and property releases for the subjects in the photos. You see these types of uses every day when you watch the evening news, open a newspaper, or check out your favorite news website.

Tip

I highly recommend attending photography-related trade shows and conferences. They are great for networking with peers, learning from industry leaders, and getting your hands on new products. Imaging USA, PhotoPlus Expo, and Photoshop World are three of my favorites.

I recently attended the Imaging USA 2010 Convention and Expo. One of the coolest items I saw there was The Polester, a telescoping pole with a camera mount on the top and a built-in remote shutter release. I got a chance to test-drive one, and with my camera about 15 feet off the ground I snapped a few shots for what I hoped could later be stitched into a panorama. I published the resulting photo (Figure 4.2) on my blog in a story about my experience at the expo. In this type of editorial use, I did not need to acquire model releases for the people appearing in the scene, nor did I need to remove logos or the many copyrighted photographs you can see on display.

Figure 4.2. The view from 15 feet above the floor of Imaging USA. © Rob Sylvan

Generally speaking, what might get accepted for editorial is variable because most sites are looking for content that will have a large potential audience. Celebrities, nationally known politicians, and world events are more in demand than your local school board meeting or a random person walking down the street.

The editorial option is worth investigating if you are interested in creating that type of content, but research each site individually to learn what subjects the sites are most interested in so you don’t waste your time. The bulk of the business of microstock sites falls under the standard royalty-free license, so let’s focus on what you will need to get your photos accepted.

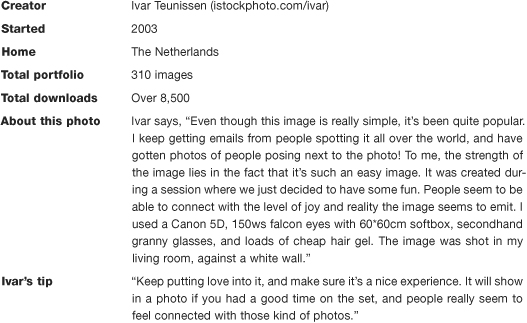

The Role of the Model Release

When you ask someone to sign a model release you are asking that person to do two things: to give permission for his or her likeness to be licensed in a multitude of ways, and to agree that all rights to the image belong to the photographer. It doesn’t matter if that person is a professional model, your mother-in-law, or even yourself. As people, we are all protected by laws (publicity laws) that give us the right to determine how our likeness is used by others for promotional purposes.

The act of getting a signed release opens up many more doors for how you can license a photo that contains a person. If the person is the primary subject in the photo, then you can expect it won’t even be accepted at most sites without a signed release. It has become the job of the photographer to acquire the signed release because the photographer has the greatest access to the individual in the photo at the time of the shooting, and the photographer is the one making the decision to license the photo in the first place. Don’t waste your time trying to figure out how much of a person has to be in a photo in order for a release to be required. Just ask the person if he or she would be willing to sign a release, and then you will be covered if you need one down the road.

In my experience, most people new to submitting work to microstock sites start by using people who are closest to them: Friends, family, and self-portraits are the norm (some of the most successful contributors use themselves as their primary model). Asking for permission to use someone’s likeness is an act of respect for that person, and it creates an opportunity for you to discuss all the possible ways that image might get used. Bring along your folder of clippings to help provide visual examples of potential uses. Believe me, you don’t want to get a call from an upset friend/family member/lover (or heaven forbid, ex-lover) wondering how his or her photo ended up in an advertisement or on the package of some product without his or her knowledge. It is a lot more fun and rewarding to involve them right from the start and manage expectations for what could happen. Not everyone is interested in signing a release, and that is perfectly understandable and should be respected.

Tip

Head over to www.istockphoto.com/license.php to find links to versions of releases in 13 languages.

You will find that each site has electronic copies of its own model release you can download for free. However, you will also find each site might have a nuanced take on what elements make a release acceptable. The best advice I can give is to use the release from the site with the strictest standards (which in my opinion is iStockphoto) to increase your chances of it being accepted at the most places. It is perfectly acceptable to print a release on your own letterhead if you prefer. What is most important is that you do not leave any fields blank.

Finding People Willing to Model

If you are not surrounded by people who are willing to sign a release, and you are not interested in stepping in front of the camera, then you might consider looking for models by placing advertisements or contacting local modeling agencies. A common path taken by many microstock contributors is to enter into a trade arrangement with a model that exchanges the model’s time (and signature on a release) for a specific number of prints (or electronic copies on CD) that they can use for their own portfolios and promotion. You might hear this referred to as TFP (Time for Prints or Time for Portfolio) or TFCD (Time for CD) or some variation on the theme. Craig’s List (www.craigslist.org), One Model Place (www.onemodelplace.com), and Model Mayhem (www.modelmayhem.com) are good resources to check out for finding models in your area.

One other great resource worth exploring is your fellow microstock contributors. Many sites have extremely active communities of members (I’ll cover this more in Chapter 12) who arrange events that are equal parts social events and photo shoots. I’ve been to quite a few, and they are a blast. They are great learning opportunities and an excellent way to share the costs associated with locations, models, props, and equipment.

Can I Get a Witness?

Finding a model is the first step, but it is also in your best interest to have a neutral third party (who is at least 18 years old) on hand to witness the model signing the release. This third party’s sole job is to witness the signing of the release. They don’t need to be present at the time the photo was taken, and they don’t even need to see the photos. All they need to do is see the model signing the release, and then they also sign and date the release right after the fact.

This may seem like overkill, especially if the model is someone you know, but it is a precaution worth taking for your own protection, and most sites require a witness signature on the release. The one instance where a witness is usually not required is in the case of a self-portrait since there is little chance you will sue yourself.

Objects do not have rights like people do, but there are issues you need to be concerned with regarding the objects that appear in your photos intended to be licensed as royalty-free stock.

A Healthy Respect for Property

An object’s design can be protected by copyright. However, simply taking a photo of that object does not violate its owner’s copyright. Where it can get touchy is how that photo might get used as defined in a typical royalty-free license. Some objects and designs become associated with a company’s identity because they are legally trademarked and used precisely for that purpose. For example, a company’s logo is a very recognizable symbol of the organization’s identity, and a lot of money is spent protecting how that identity is used. So when you produce stock images, you need to be very mindful of the objects you use as props so that you can avoid including problematic content in your photos, such as logos and trade names. There are other things, everyday objects, and you need to seek out the most generic-looking and nondescript versions to use as your stock photo props. Remember, good and useful stock photos are extremely generic so that they can communicate their message simply.

Prevention Pays Off

We’ll spend some time going over how to remove problematic elements from your photos after the fact using software solutions in Chapter 9, but the most efficient way to remove problem items is to do it before you trip the shutter. Here are a few tips:

• Survey the scene for logos, trademarks, and copyrighted subjects before you shoot and keep them out of the frame.

• Ask your models ahead of time to wear generic clothing that does not carry logos, and then bring some extra clothing items for backup if needed.

• Use shallow depth of field to blur problem content so that it is unrecognizable.

• Find a camera angle that obscures problem content.

• Cover, move, remove, or otherwise physically obscure logos and problem content.

If you have an object that you want or need to be the primary subject of the photo, find out if it is possible to acquire a property release from the copyright owner. A common scenario is when a painting is used as a prop in the background of a room setting. Some photographers will simply use software later to replace the painting with an image for which they own the copyright, or, if they know a painter, they’ll try to get the artist’s permission to use a painting in the scene.

A property release does the same job as the model release, which is to grant permission for the use and to agree that the photographer owns all the rights to the photos that are created during the shoot. You can find a sample property release at www.istockphoto.com/license.php.

The context in which the object is used in the photo is a primary factor in determining how problematic it might be. For example, a stuffed Beanie Baby™ teddy bear on a plain white background would be a problem, but that same bear sitting on a shelf in the background of a photo depicting a child doing homework could be just fine. I’m sorry to say there is no easy answer, but keep in mind that most sites tend to err on the side of caution when evaluating submitted content, so you should, too. You’ll soon learn the common mantra recited by all experienced microstock contributors, “When in doubt, clone it out.”

Being Inspired by Others (But Not Too Much)

Figure 4.7. Short Superhero. © Andrew Rich (www.istockphoto.com/RichVintage)

There is nothing wrong with being inspired by others to do great things. We all have heroes and role models who we aspire to emulate. When it comes to art, artists have been influenced by other artists since the first drawing went up on the cave wall. These days we are surrounded by images at every turn, and it is impossible to not be influenced by what we see in some way. I’ve long lost count of how many images have passed before my eyes, but I still find myself awestruck on a regular basis by some new image that makes me think, “Dang! I wish I could do that!” I file those images away in my mind and try to figure out the qualities that caused me to stop in my tracks. Those qualities inspire me to improve my own work in the hope that I may one day have the same effect on someone else.

Tip

The US Copyright Office allows you to create a public record connecting you to your work. It’s a completely optional process, but something you should be aware of before letting your work go out into the world. The American Society of Media Photographers has an excellent resource and walk-through of the copyright registration process. See http://asmp.org/tutorials/best-practices.html.

When you create an image, it is your expression of the subject that is copyrighted, not the idea that served as the inspiration for its creation. It is not possible to copyright a concept or a subject. If you create an image after being inspired by someone else’s image, it is your job to respect that artist’s copyright by making your image your own unique expression. Think about all the elements of a photo that the photographer can control to express his or her vision, such as:

• Choice of subject

• Arrangement of subjects

• Quality of light (time of day, harsh, soft, intense, diffuse, warm, cool, and so on)

• Camera angle (head on, far away, close up, from below, from above, and so on)

• Choice of colors represented

• Choice of background and negative space

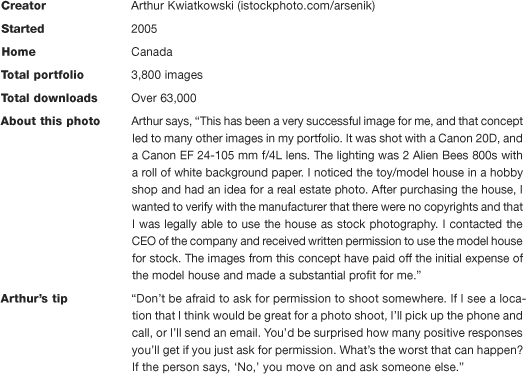

Figure 4.8. Three different takes on jogging. Collectively downloaded over 13,000 times. (www.istockphoto/blublaf, www.istockphoto/amygdala_imagery, www.istockphoto.com/EricHood)

There are many more variables, but each deliberate creative choice is part of your unique expression that contributes to the overall look and feel of your photos, and over time, may become the hallmarks of your particular style.

In the world of stock photography it can be a challenge to produce completely unique work because customers like to have a variety of images to choose from on any given subject—jogging, for instance. A search on jogging (Figure 4.8) would show there is a lot of publicly available data, such as download totals, that might indicate that jogging photos are in high demand. You have the responsibility to respect the copyrights of your peers and not simply copy their jogging photos. But no one owns a particular subject or idea, and the more common the composition, the harder it is to make a case that no one else can create a photo the same way.

For example, consider a pair of horseshoes on a white background (Figure 4.10) or pretty much any common object on a plain background, for that matter. There is no judge or jury in the world that would decide that only I can create stock photographs of horseshoes on plain white backgrounds. I may own the copyright to this particular photo, but when it comes to such commonplace subjects and plain compositions, it just isn’t fair or reasonable to grant a monopoly to a single person. The less common the objects, and the more creative you are in creating the composition, the more complex the issue becomes.

Figure 4.10. Horseshoes. © Rob Sylvan

This is a complicated issue to do justice to in this small space, but be respectful as you create new works. Take inspiration from what you see around you. Do not become a human copy machine creating reproductions of other artists’ works as a shortcut to creativity.

Assignment

Take a close look at the three photos in Figure 4.6. Grab a sheet of paper and draw three columns. Label the first column similarities, the second column differences, and the third column the core message (what you think a photo is trying to communicate).

With that in mind, choose a message you would like to illustrate with a photo of your own. Carefully consider all the elements at your disposal for creating an image that is similar in theme, but different in execution. Then do it! Don’t worry about it being good enough to submit for stock. The point of the exercise is that there is so much learning involved in the doing that the thinking alone cannot achieve.

Bonus points: Print out a model release and approach someone you know and ask her to be your model. Show her your clip file and discuss all the possible ways this photo could be used.