25 Pictorial Tension between Two Elements

Two opposing poles create magnetic tension, and something similar happens with pictorial tension. However, how do you provide tension in a photo?

You already saw how a photograph with good composition consciously leads you through the image, and you also learned how photographs can be rhythmically composed. Now I am going to explain how to achieve pictorial composition by concentrating the center of attention in two poles and including some rhythmic elements in it.

If you reflect a bit about composition in photography, you’ll realize you probably tend to choose a particular subject such as a pretty house, a person, or a special tree and then you place the subject either in the middle or (a better alternative) in the golden ratio. This is not necessarily bad; in most cases, you get rather calm photos, but in the worst-case scenario, you get boring images.

To avoid boring photos, you can compose a picture with two centers of attention and place them preferably toward the edges to achieve a so-called bipolar pictorial composition. If the two poles are equivalent, the composition does not let the eye rest because it will always keep moving back and forth between the two centers. Our eyes love this kind of restlessness, which imparts a dynamic quality to a photo.

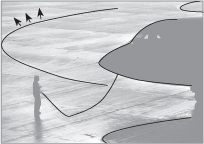

Airplane on the Line

Man and technology represent two poles of tension that have influenced our world in an amazing way in the last 100 years. Aviation is only one example demonstrating that humans can surpass their own limits in many different ways.

Here (figure 25–1), pictorial tension is created by both the abrupt crop of the airplane and the backlight that reduces man and machine to strong silhouettes. However, the composition is also determined by a third element, namely the repeating shape of the arch that also provides the pictorial rhythm. The arch determines not only the form of the airplane nose and its shadow, but also the shape of the cable and the two traces on the airport surface.

In this photo, pictorial tension has a formal and content-related component because it might provoke philosophical talk about the tense relationship between man and alleged technological marvels. In the meantime, this image could very well represent not only something positive—how mankind has advanced technologically—but also something negative because aviation can contribute to global warming. Humans invent outstanding technology, but they may become technology’s victim in the future.

The photo was taken with a 200 mm telephoto lens and an analog Nikon F4.

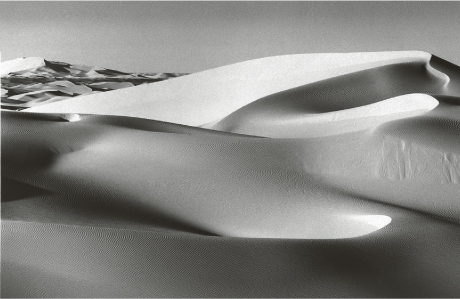

Dunes in the Sahara

The Sahara is one of the most fascinating regions on this planet. The region’s seemingly endless expanse of sand dunes cries out for a good composition. In the photo in figure 25–2, the early morning or late afternoon hours create an interesting interplay of light and shadow because the sun is very low. To make sure the landscape does not look too monotonous, the sand dunes provide pictorial tension. In this sea of sand dunes, an especially large dune provides a counterweight to the smaller dunes in the bottom left. However, what provides most of the tension is that the large dune has been placed too far to the right. Another dune in the background (left border) creates a counterweight. If you cover the left third of the image, you can notice how the photo loses its balance and seems to tilt to the right. The total picture is balanced, however, because the sand dune chain located in the upper left is the counterweight to the large dune that is placed too much to the right. All these elements provide a strong tension in this balanced photo. The photo was taken with an analog camera and a 105 mm telephoto lens.

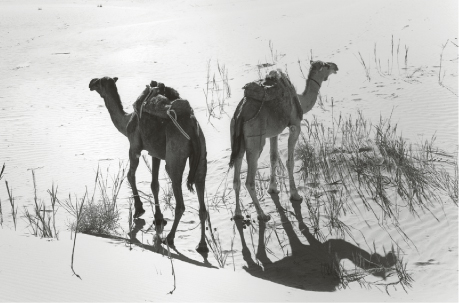

A Glance out of the Picture

For a long time, serious photo clubs emphasized a classical rule of composition: People should not move out of the picture, but rather into it. This seems logical at first because such a composition leads your gaze into, not out of, the picture. Modern pictorial language, however, no longer follows this classical rule, because it is perceived as overly conventional. In photojournalism, we often see people in the edges of pictures looking away from the camera or their blurred images moving out of the photos.

In the next photo (figure 25–3), instead of humans, two camels turn away from each other. Each one leads your gaze out of the image—yet, this is what gives the photo considerably more tension than if both camels had turned toward each other. The eye is forced to move back and forth between the two directions indicated by the camels, and yet the photo has sufficient calmness because it has an axis of symmetry (although this axis has been slightly broken because only the shadow of the right camel can be seen). This prevents the composition from becoming too rigid. The photo was taken with an analog camera using a 105 mm telephoto lens.

Spotlight

An Irish landscape is usually characterized by dark clouds and saturated greens, therefore black and white photography may not be the ideal medium to photograph it. And yet, precisely because black and white will not register these saturated colors, the interplay of light and shadow, rather than color, composes the image (figure 25–4). A green mountain such as this one would be completely uninteresting for a black and white image if not for the exciting, endlessly changing lights and shadows falling on it, which make the landscape exciting. The trick is to make use of this interplay of light and shadow to compose and create tension; in this photo the lower circular spotlight is what gives the image all its tension. If you cover the spotlight, the photo loses its tension and the entire lower part looks dead. You have learned that the eye is led through an image by contrasting spots, and in this photo there are two contrasting spots, or poles, that provide tension: the light spot in the cloud to the left and the elongated light spot on the mountain that leads the eye left to right and stops just before it reaches the edge. (A third tension pole is located between this elongated light spot and a smaller one in the lower part of the image.)

The photo was taken digitally with the 87 mm focal length of a Canon 70–200 mm telephoto lens. I used Photoshop’s Dodge tool to brighten the light falling on the mountain by about 15%. The medium-tone contrast of the image was also increased by about the same factor.