29 How to Compose with Blurred Movement

Long exposures play an increasingly prominent role in today’s modern artistic photography. A photographer who has used long exposures to the max is Michael Wesely. His yearlong exposures of Berlin’s Potsdam Square have been exhibited internationally. Only wall fragments remained stable in his photos, everything else looks dynamic and chaotic, almost resembling a futurist painting of the early twentieth century.

It’s fascinating how photography is capable of breaking through our conventional perception by blurring what we experience as individual, clearly separated moments that are strung together. In Wesely’s images, these moments just dissolve into a blurred flow from which countless instants of an entire year become one single complete view.

In another series that can be seen as further development of his extremely long exposures, Wesely does not leave his camera on the same spot but begins twisting it horizontally during exposure. The results are unfocused landscape photos in which the horizontal axis is completely blurred, thus becoming a fuzzy interaction of multicolored stripes in which details are no longer recognizable, reminding the viewer of Mark Rothko’s paintings. These photos can also be regarded as allusions to the stripes seen on the bar code stickers found on all kinds of merchandise.

In contrast to long exposures, world-famous photojournalist Henri Cartier-Bresson formulated the “decisive moment” style of photography by waiting until the fraction of a second that makes the right statement; what has been dormant suddenly breaks out and gets to the heart of things.

With long exposures, on the other hand, this moment blurs, allowing time to flow and mix. Naturally, these long exposures make you think philosophically about the nature of time. What is it? How can it be grasped? How can time, as a basis of photography, be played with? Almost every photographer has tried to answer these questions.

Long exposures are as old as the beginnings of photography; when the rather insensitive emulsions finally gave way to short exposures, it revolutionized the medium. Currently, we can freely choose between ![]() s and long exposures that last entire evenings or over one year, as with Wesely. Technically speaking, long exposures are no longer a problem; even good digital cameras allow you to go beyond the 30-second exposure and shoot with a B (long exposure) setting. The indispensable tool for shooting good-quality, long exposures is a stable tripod that is strong enough to withstand a heavy telephoto lens (added weight), a vertical format (less stability), and wind. The tripod should weigh at least 5 pounds, and you should preferably stay away from very lightweight ones made of plastic. It is better to purchase a stable tripod even if height concessions must be made due to weight issues. A shooting height of 51 inches is enough for almost all subjects.

s and long exposures that last entire evenings or over one year, as with Wesely. Technically speaking, long exposures are no longer a problem; even good digital cameras allow you to go beyond the 30-second exposure and shoot with a B (long exposure) setting. The indispensable tool for shooting good-quality, long exposures is a stable tripod that is strong enough to withstand a heavy telephoto lens (added weight), a vertical format (less stability), and wind. The tripod should weigh at least 5 pounds, and you should preferably stay away from very lightweight ones made of plastic. It is better to purchase a stable tripod even if height concessions must be made due to weight issues. A shooting height of 51 inches is enough for almost all subjects.

Exposure is no longer particularly difficult either: If you use black and white negative film, I generally recommend slightly overexposing by one to two apertures when shooting at night because exposure meters are easily fooled by neon lights and thus indicate a higher light intensity than is really available.

Handling the exposure using a digital camera is even less of a problem because you can control the image perfectly with the histogram on the display. If necessary, you can correct the image by reshooting it.

Chapel in a Sea of Grass

In the photo in figure 29–1, the entire foreground is immersed in blurred movement while the chapel in the middle of the image remains perfectly sharp. The photo was taken from the window of a moving train while traveling between Hanover and Brunswick. The shutter speed was ![]() s; long enough for making the field in the foreground appear out of focus, yet short enough for the houses, trees, and the chapel on the horizon to be in perfect focus.

s; long enough for making the field in the foreground appear out of focus, yet short enough for the houses, trees, and the chapel on the horizon to be in perfect focus.

The photo suggests that the chapel is in the middle of the sea and not behind ordinary fields. To intensify the magical impression of this photo (taken with an analog camera), I strongly burned in the sky toward the top in the darkroom. Thus, the surroundings of the chapel are flooded with light and an impression of spatial depth is thereby created. All pictorial means have been used to give this small, rather inconspicuous chapel a special charm, and the blurred movement is the main reason for this.

Typical Night Photo

When taking a photo of the Paris Opera House (figure 29–2), I closed the aperture so much that the automatic counter of my exposure meter exceeded 30 seconds—enough time for coincidence, my “companion,” to create a composition. In the finished photo, a passing bus going into a side street produced an interesting composition that broke the central perspective fixed on the Opera House. The two elements that make the composition especially interesting are the lettering that is reflected in the windows of the bus and the bright line that goes across from the top to the right edge of the image. However, all other lines created by the long exposure also give the photo a dynamic quality that very clearly expresses metropolitan effervescence: a typical, classic night photo.

One more thing: When shooting long exposures, you must be aware of the reciprocity effect that occurs when aperture changes are no longer proportional to exposure time (i. e., you cannot compensate for a very long exposure by changing the aperture). However, in practice this effect plays a much lesser role than photo clubs often attribute to it. The photo was taken with an analog camera using a 105 mm focal length.

Long Exposure with Displacement

I took the photo of the World Trade Center (figure 29–3) in June 2001, not even three months before the tragedy that took place on September 11. Seen in retrospect, it has an almost anticipatory character, although I only intended to use it as a long exposure experiment. The camera was mounted on a tripod and set to a very small aperture (f/16) and an exposure time of 20 seconds, during which time I displaced the camera vertically. The pictorial effect is disturbing, especially when we remember that three months later the main subject of this photo became the victim of the most brutal terrorist attack ever.

Needless to say, this long exposure would one day have a significance that could not have been foreseen at the time the photo was taken. The effect of this vertical displacement implies, in fact, the disintegration of the solid structure. The elongated lights do give the impression of a fire, and the vertical lines emphasize this impression of collapsing stability.

Blurred Movement in the Daytime

Long exposures can also be achieved in the daytime. One method is to use a neutral density (gray) filter to lengthen exposure time significantly. If there is no such filter at hand, another possibility is to use a low ASA number and shoot with the smallest possible aperture to reach shutter speeds of ![]() or

or ![]() s.

s.

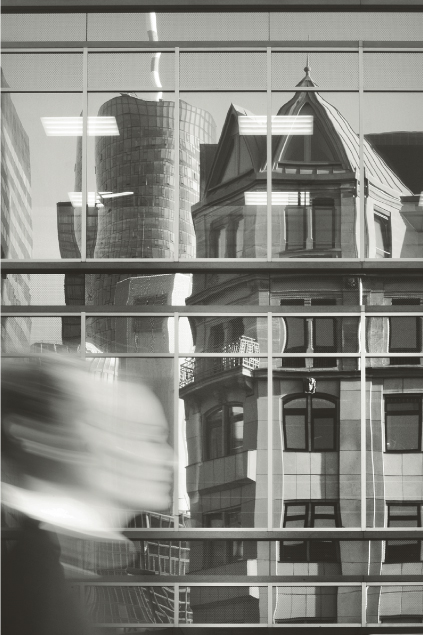

You can see the result of a long exposure in this composition based on architectural lines that are, by themselves, not very exciting, but the blurred face at lower-left creates tension. In a lively city such as Frankfurt, with patience and some luck, you will see a person walk by in the right position. Naturally, you must be a keen observer of the surroundings to know exactly when to release the shutter. Another possibility would be to take a friend and tell him or her when to start moving in front of the camera.

For these kinds of photos, digital cameras are ideal because the result can be seen at once and you can repeatedly shoot the photo until the image is satisfactory. In this case, triple pictorial tension was created among modern man, late nineteenth century architecture, and Frankfurt’s Main Tower reflected in a modern glass façade.

This photo was taken digitally using a standard lens. I used the Photoshop Shadow/Highlight tool to brighten the shadows by about 12%.

Playing with Motion Blur

There has recently been an increase in the number of photos that are shot deliberately blurred. This often has the appearance of being a cheap effect as it doesn’t take much skill to simply wave your camera about during nighttime exposures. If you want to use blur as a compositional tool, you should use it carefully and in a considered fashion. In the photo in figure 29–5, I used a neutral density filter to artificially increase the length of my daytime shutter speed. I moved the camera during the 10-second exposure to create a blurred repetition of the outlines of the church towers. This produced a photo with a strong graphical feel that is reminiscent of the style of Lyonel Feininger.

The photo was taken using a 200 mm telephoto lens and was converted to black and white using Photoshop. Contrast was significantly increased.