Lynne Pritchard (see Figure 14.1) is a stop-motion animation artist from London, England. Coming from a theater background, she has worked on several stop-motion studio productions as an animator, set builder, and model maker. She also teaches workshops and lectures on animation for several different colleges around London. I first met Lynne in 2005 when she came to VanArts to take a one-month summer intensive course in computer animation. Her Web site is www.gingermog.com.

KEN: Lynne, which stop-motion programs inspired you, growing up in the UK?

LYNNE: I was a small child in the late ’70s, and this was a great time for stop-motion in the UK, and my mother had no problem in letting the TV entertain me for a few hours at a time, which I greatly thank her for. I have no doubt in my mind that the animation I watched as a child helped feed my imagination and sew the seeds for my future career.

A big favorite with me and many other people of my age is Bagpuss, created by Oliver Postgate and Peter Firmin of Smallfilms. Bagpuss is a “saggy, fat, cloth cat” who lives in a strange, forgotten shop with his friends, Madeline the rag doll, Professor Yaffle (a woodpecker bookend), a toy frog, and many enthusiastic mice. In every episode, a strange, forgotten object is brought into the shop, and Bagpuss and friends always find out the story behind the object through charming, funny songs and inventive cutout animation. Although I suppose not much actually happens from an adult’s point of view, and the characters are simple, there is a quality of magic about this animation, something really beautiful and gentle.

Next I would choose The Wombles as an inspiring stop-motion series, created by Elizabeth Beresford. It was centered around the antics of a group of amiable creatures called “Wombles,” who live in a newspapered borough underneath Wimbledon Common, collecting the left-behind rubbish and creating labor-saving gadgets that always end up creating chaos. There is a strong theme of recycling and mend-and-make-do, which appeals to most UK residents of a certain age, and I imagine all stop-motion animators hoard old tins of paint, lolly sticks, cardboard, bits of old plastic toys, etc., “just in case they come in handy one day,” which I’m really guilty of.

Finally, I would choose Cosgrove Hall’s Charlton and the Wheelies as a superb, slightly surreal animation aimed at younger kids (I think) but also a little bit scary due to a cackling witch, who lived in a black tea kettle and had spies who were mushrooms who would pop up in unlikely places and had staring eyes. Chorlton, the main character, was friendly enough, and most of the characters whizzed about on wheels (an excellent way of avoiding difficult walk cycles!).

At the time, I greatly enjoyed other children’s stop-motion series such as Cockleshell Bay and Portland Bill, but they were forerunners of “sensible” children’s stop-motion series like Postman Pat and Fireman Sam, which although engaging and lovely, the characters and environments are drawn from real life situations and have “safe, believable adventures.” Personally, I like to be transported to another place—you get enough of the real world around you every day; animation gives you a chance to push the boundaries, to live in that world you find through the wardrobe...but maybe that says more about me.

KEN: Were most of the shows that inspired you British productions, or were there any from other countries that stand out in your memory?

LYNNE: As a young child, although most of the animation I watched was made in the UK or imported American cartoons, I did have exposure to some Russian and East European animation dubbed in English, which was much darker with odd, stylized puppets. These films would be shown at odd times during the day and looked totally different from British animation. I probably watched Lotte Reiniger’s fairy tale adaptations, as I remember many of them consisted of cutout animation. Also, as an older child around eleven, I saw Harpya by Raoul Servais, a nightmarish tale of a man followed home by an evil mythical creature who is half-woman half-bird and proceeded to torment him, possibly eating him alive, if I remember correctly. The film has very haunting imagery, which made me realize that stop-motion was not just a medium for warmhearted children’s entertainment but could be a medium for darker, expressive, more intense storytelling. From the U.S., there was the fantastic partnership of Rankin-Bass, who created one of my all-time favorite stop-motion films, Mad Monster Party.

KEN: On the surface, from a North American perspective, many people get the impression that the UK is one of the biggest havens for stop-motion production, perhaps more so than over here. How is the scene over there from your perspective?

LYNNE: I never thought of stop-motion being quintessentially British before, as I would have said Russia and East Europe were the biggest producers of stop-motion animation. Certainly, in the UK, we have some hit companies such as Aardman Animation and Hit Entertainment, whose work is known internationally and who have been great commercial successes, but my students from India have grown up watching Gumby, which I have never seen.

As a stop-motion animator who also works in 2D, I would say one of my biggest frustrations is that stop-motion is frequently dismissed by producers as being just for small children up to the age of five or six, and after that children want something with more action, faster, not so soft and cutesy. I would really disagree with this; a lot of 2D animation is produced because it is fast and cheap in comparison to making a stop-motion alternative, and I think companies such as Aardman with their films and adverts have been pushing the boundaries of what can be achieved with stop-motion animation, altering people’s perception of the medium. Tim Burton’s Corpse Bride (an American/Anglo production) certainly wasn’t a small children’s film; this film wasn’t about cute little puppets existing in a safe, colorful world. Corpse Bride is a melancholy, gothic tale with glorious detailed sets and puppets, appealing to a much older audience, again opening the medium to a wider market. A few years ago in the UK, we had a stop-motion series called Crapston Villas, produced by Spitting Image, which went on air very late in the evening, as the antics of the puppet residence of a decrepit group of flats was far too risqué for small children’s eyes.

I think stop-motion is still seen as a novelty in the UK, often overlooked by the massive 2D market, but things are changing, and as so many animators now work in CGI, which a few years ago looked like would take over stop-motion (but hasn’t), there is a quiet respect for those who still work in a medium that you can actually touch with your hands.

KEN: So how did you get started working with stop-motion animation?

LYNNE: As a child, I was an avid model maker, making entire small-scale towns inside my room made out of any materials that came to hand. I drew all the time, mostly characters I invented and the imaginary worlds they lived in. I wanted to be a comic book artist until a visit to the Pantomime when I was 11, where I became transfixed with the beautiful sets and decided to be a theatre designer. It was at Theatre College seven years later, where we designed scaled-down theatre sets and I had access to a model lighting studio, that I really became drawn into animation. I found myself happily spending eight hours at a time in the darkness of the model lighting studio, experimenting with the scaled lights and my model set designs, reproducing different lighting effects. I used to record them with a stills camera, and it wasn’t long until I started moving the model actors around and fell heavily in love with the idea of becoming an animator. So I decided to gather what resources I had, bought myself a secondhand Super 8 camera out of the local paper, and watched all the stop-motion animation I could, with a stopwatch in my hand trying to work out the timing. The only book I could lay my hands on about animation was Tony White’s The Animator’s Workbook, which is for drawn animation, but I could adapt some of the basic animation principles to stop-motion. I later spent some time doing work experience at his studio Animus and at Griffilms. Both studios created 2D animation, but I was desperate to get any animation experience that I could.

In my final year at college, although I was actually on a theatre design degree course, I somehow convinced my tutors to let me specialize in animation for my final-year project. This led to [my] making a series of very badly animated but imaginative stop-motion films where I experimented with lots of mediums, colored glass, sand, paint, Plasticine, latex and wire-frame armatures, even ice. Thankfully, my roommates were very patient about the saucepans of sand I dyed on the stove and having little Plasticine models encased in ice blocks nestling among the frozen peas.

After college, I put together a portfolio and a show reel of my work and approached around 20 animation studios, eventually receiving an interview at Ealing Animation, a studio which specialized in stop-motion and 2D graphics, where I was appointed production assistant. I’m sure originally they intended me to stay in the production team, but I had other ideas. My real ambition was to work in the stop-motion studio, which was in the basement, several floors below the 2D studio. As production assistant I was lucky enough to work with both departments and got to know the animators well. The team director, Kevin Griffiths, knew I was very keen and gave me jobs such as prop and material-buying and often requested me to do photocopying and other organizational work for the stop-motion department. After six to nine months I became a full-time assistant model maker, and with the kindness and generosity of the other stop-motion animators, I learnt all I could about stop-motion animation, and within two years had worked my way up to being the assistant to the director, who was at that time Liz Whitaker. Since then I have just kept on going.

KEN: Which projects that you’ve worked on are you the most proud of, or were the most challenging?

LYNNE: My most recent challenging project was eight minutes of animation for a new BBC Digital Web site. I only had eight weeks to devise a character, build the puppet and sets, animate, and edit it. It was extremely tough to get it finished for the deadline, and in the final weeks, I was working 14 to 16 hours a day. Crazy hours are all part and parcel of an animator’s job, but my non-animator friends do think it’s a bit insane how much time and effort I put into my work. Fortunately, my husband works as a computer programmer, a similar time-consuming occupation, so we can appreciate why we spend so much of our time working and how important it is to get things to be the best they possibly can be.

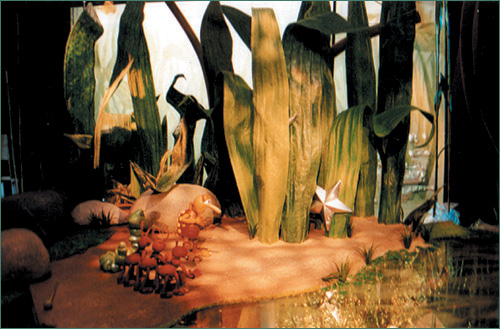

Some of my favorite projects to work on were for kids TV. Shrinking Violet (see Figure 14.2) was a pilot produced by Elephant Productions, and this still stands out as one of my favorite projects I worked on. There were only two model makers working on the sets, myself and Graeme Owen, so I had the opportunity to design and make a lot of the set. Also, it was a bigger scale than I had been used to working on since leaving theatre. The tree we carved was taller than I am (5′ 6″). I was able to use my set-painting skills for the background, and to create all the different greens of the grasses and leaves, I got inventive and spent hours mixing standard dye colors into these glorious colors (which luckily didn’t stain my bath permanently).

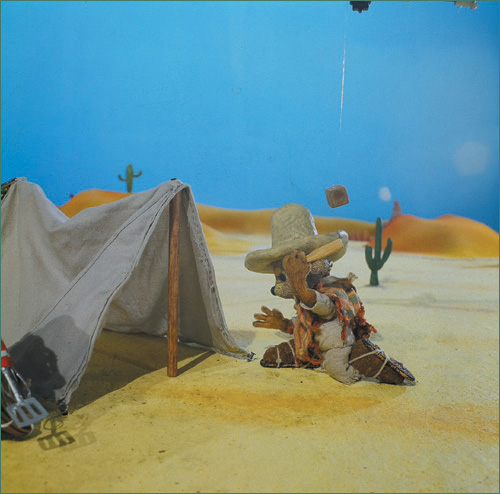

El Nombre (see Figure 14.3), one of the first series I worked on, is a favorite, too; Christopher Lillicrap is such a clever screenwriter, and although we had a low budget, we created a great set. The original set was modified out of cardboard boxes, but you would never guess! I like that alchemy part of stop-motion: the world you re-create for the camera becomes totally real. It was a hit with kids and students who were skipping lectures and later became a bigger series in its own right with a more elaborate set. I liked working on Numbercrew, too; by the end of the second series, I had churned out literally hundreds of props. It was hard work, and I had to learn on my feet, but I am grateful to the director Liz Whitaker for allowing me to have so much responsibility, which enabled me to learn a lot. I had the opportunity to design my first sets on this series, which was a step up from doing all the little props no one else wanted to do.

Figure 14.3. Set design from El Nombre by Lynne Pritchard. (Copyright 1999, The Santa Flamingo Corporation Limited.)

I am always trying to improve my animation technique, and on almost every project I take on, I learn something new, be it a different solution to creating an effect, a better way of animating a character, or a new software program in post-production. Animation is changing so fast there is no time to stagnate; I hope I always continue to keep on going forward. I would be worried if I felt I wasn’t learning anything new.

KEN: What kinds of projects are you currently working on?

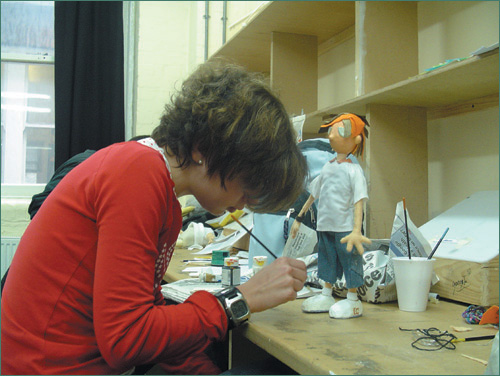

LYNNE: The project I am presently working on is for Golden Cage Films, where I’ve designed the puppet (see Figure 14.4) and made the set for the film they have written and will help out with the animation. After this project is finished, I’m designing some characters for a pilot.

What I am really excited about at the moment is that I have joined forces with my creative partner Ellen Kleiven to form Ellefolk (www.ellefolk.com). The name Ellefolk derives from the Norwegian word for light elves, a group of mischievous little people derived from Elfish folk who live in the woods and lowlands of Norway, who can change form, foretell the future, sing, and compose fascinating and enraptured music. We both share a love of mythology and fairy tales and are extremely enthusiastic about animation, especially about mixing up different technologies and experimenting with techniques.

We are presently working on a few projects, fitting the time to work on ideas around commercial jobs. (After all, a girl has to eat, and there are bills to be paid.) I’ve got a lot of ideas buzzing around my head at the moment, which is great. My main problem at the moment is finding the time to do everything, but I’d much rather be frantically busy than uninspired. It’s a good time creatively for me right now.

KEN: What challenges do you find in teaching stop-motion to students?

LYNNE: I think one of my biggest challenges was actually starting to teach stop-motion animation. I was asked the very day after finishing my post-grad in character animation to step in and bridge an emergency gap in an established computer animation course, where the students needed to learn more about animation. The thought of standing in front of a class and actually teaching petrified me! I had one voice in my head saying, “But you don’t know anything!” Luckily, the freelancer part of my brain, which never says no to a job, kicked in and I heard myself say, “Sure, I’ll give it a go.”

Although I had worked consistently in animation for about six years before my post-grad, I still felt very wet behind the ears with a lot to learn. I had mostly worked with guys with over 20 years experience in the industry, so I have a standard that it takes years to become a good animator. However, a wise animator friend, Paul Stone, advised me that I probably knew a lot more than I thought I did, so armed with a tool box of materials and a hastily devised handout on how to make a balsa and wireframe puppet (I felt I had to have a handout to be a proper teacher, and it also helped organize my thoughts), I faced my first class of CGI animators. And they loved it! And surprisingly, I could help them; I could see their animation getting better week by week...it was working! So after my first six sessions were up, to my surprise I was asked back to teach the next term, and since then I’ve been developing the course, pushing it further and further each term. I didn’t realize before that teaching was such a two-way thing: You give out a lot, but you get so much back in return. It’s stimulating but exhausting; the students are so inventive; they make me think of things in a different light. I also continue to work in the industry, and I think that helps the students, as I am honest that it’s not an easy industry to survive in, but if I am making it, so can they.

In the past, I have been worried that one day I would have a die-hard CGI student who only wanted to work on software packages and give me a lot of attitude about doing girly puppet stuff (sorry guys, no offense; I know most stop-motion animators are men), but so far it hasn’t happened. Most of my students are male and want to work in CGI animation and can be initially surprised when they find themselves in my class and I bring out the wire and glue. However, I convince them that animating with a puppet is very similar to animating a rigged character in a CGI and if you can animate well in stop-motion, using straight-ahead acting, then you can animate anything. (Well, that’s a line I give them anyway.)

I’ve studied CGI packages, and I understand how frustrating it is to most of us (whiz kids aside) that we can’t get the computer to do what we want. We have an idea in our heads what we want to create, but somehow we just can’t re-create it, and our attempts are a poor imitation, until we get to grips with the software, which takes a while. I feel that my stop-motion class gives the students who feel like this a break. In a session, or two they can create a puppet and get straight to experimenting with moving it around in space. Yes, their first attempts are usually way too quick and a bit wobbly, but I ask them to analyze their animation and see how they could improve it. Often students try to be a bit too ambitious with their first scenes, but it does give them the opportunity to be creative without being intimidated by the software. I point out that what they learn in stop-motion class, they can bring back to their exercises they are working on in CGI. Frequently, students are disappointed that the stop-motion software won’t add in animation between key frames and that they have to go back and reshoot that scene again, but it does give them a chance to think about what they are animating.

My classes give students an opportunity to be openly creative; some of them haven’t used their hands to make things since they were small children, and they often surprise themselves. Making things is part of unlocking the creative process. We talk a lot in class, ideas bounce back and forth, and we experiment with new ideas. I want my students to enjoy my class, but I don’t want their work to be sloppy. I’m serious about the students producing good work; it takes time to be a good stop-motion animator, too. Depending on the college I’m working at, I usually teach between 7 to 14 students. It’s less hectic when there are fewer students, as there are more computers and other equipment to go round. When 14 people are straightening and twisting aluminum wire all at the same time, things can get a bit crazy, especially if the classroom isn’t very large. You need some space to lay out the materials and tools, for students to work on their models and to animate in an area where hopefully you can control the light, and the tripod isn’t in danger of being knocked.

KEN: I can certainly relate to much of that! What kind of equipment do you use in your classes?

LYNNE: The materials I use are aluminum wire, balsa wood, foam, foam board, cork board (shower mats from B & Q), Plastizote foam (one of the hardest materials to acquire since it’s used for packaging really expensive medical equipment, but the manufacturing factory gave me a few free sheets a few years ago), polystyrene balls, air-drying clay, lots of different glues, material scraps, wool and embroidery thread, beads for eyes, and so on; just lots of bits and bobs I find and hoard until the right occasion appears to use them.

At the moment, I tend to start the class off by showing the students how to make a puppet based on a balsa and aluminum wire frame and using foam and material to build up the body (see Figure 14.5) Aluminum wire is by no means as precise and easy to use as ball-and-socket puppets, but they would be too costly and time consuming for a regular class to make. Also, I’ve worked on lower-budget children’s series such as El Nombre, where aluminum wire frame puppets worked really well. By building their puppet first, students are encouraged to think about the character they are going to develop. Who are they? What sort of person will they be? How will they move? Later they will develop a simple narrative around their puppet through which they can practice character animation. If I’m teaching a shorter workshop, I will encourage students to use Plasticine or cardboard cutouts, as you can produce animation more immediately.

To capture the animation, I use StopMotionPro. It works on practically every PC computer I have ever installed it on and is easy to use. The onion skin facility is great when you’re first learning and getting a feel for stop-motion, and you can play back your work immediately. Normally, I edit the footage and add sound in Premiere; some of my students use Final Cut Pro. In recent years, we’ve used After Effects to do some post-production for some small special effects and green screen. I started out using digital cameras to shoot the footage, but you couldn’t use the onion skin with some of the cameras, and I really wanted my students to have access to that, so I changed to using some old Sony Video cameras we already had at college, and for my own projects, I have a Sony Handycam.

Lighting is a bit more hit and miss. Eventually, I would like to have a proper scaled-down lighting studio in the college with a set of Redhead and Dedo lights and gels, but to get enough lights for several setups would be expensive, so for the time being, I use an assortment of scaled-down and adjustable-angle poise lights bought from furniture stores such as Ikea and Habitat. It works after a fashion, but for green screening, I am working on my college to allow me a space to set up a designated stop-motion studio [that] can be used by stop-motion students who want to work on their projects outside of class. I know how invaluable it was to me as a student to have a space where I could work uninterrupted for several hours at a time. Space in any college is at a premium, but luckily my head of department is very supportive, so we should have our stop-motion studio soon.

KEN: What advice do you have for aspiring stop-motion animators?

LYNNE: My advice to anyone who has aspirations of becoming a stop-motion animator is just grab some Plasticine, or whatever material you can get your hands on, and create a character of your own. It’s never been easier to make your own stop-motion films; most people have access to a computer, if not at home, at school. You don’t need a fancy camera; even a webcam will do if you don’t have anything else. You can download free software to capture and edit from the Net, even add your own sound effects or compose your own soundtrack if you’re musically minded. There is so much information available out there on animation forums and Web sites. If you’re stuck, you can ask for advice; you don’t have to wait a week anymore for Kodak to send back your developed roll of Super 8 film only to find out you shot it all out of focus. You can also use the Web as a platform to show your work (YouTube), get feedback, and to look at other animators’ work (such as Atom Films).

Although I think you learn the most from getting your hands dirty and working out your own problems that occur when you’re animating in stop-motion, I would encourage people to look at other animators’ work. I think it’s important to stop being a passive consumer of animation and really start analyzing what it is about a certain piece of animation that makes it tick. Is it the design of the characters? The story? What makes it funny or interesting? Is it the timing of that gag that makes it funny? Who’s the animator or character designer? What else have they done? On most DVDs of recent animation films, there are documentaries and commentaries about the making of the film. Often, these are fantastic sources of information to learn from. Study other animators’ techniques; ask yourself, how do they make their characters come alive?

By all means, be influenced by other animators, but I wouldn’t recommend you rip their characters off directly. If you’re trying to re-create a famous character with a lot less resources, it is doubtful your version will be a favorable comparison. The Matrix has two sequels; do we really need to see another version of someone trying to re-create a fantastical martial art movement with a fixed camera? By all means have a go—a challenge is always a good thing—but what I am trying to say is be original, experiment, push boundaries, let your imagination go wild. When making your own animation film, it’s your very own environment you’re re-creating. Don’t worry about making an animation you think other people want to see. Create a film you, yourself, want to see.