In addition to stop-motion, there are two other major animation mediums that exist today and that are mentioned in this book for comparative purposes: 2D animation (also referred to as classical or traditional) and CG (computer-generated) animation (also referred to as 3D or digital). The 2D medium was first made famous in the U.S. by Winsor McCay, who amazed audiences with this novel idea of “drawings that move.” Since then, some of the artists responsible for animation’s success include Walt Disney, Tex Avery, Chuck Jones, and Hayao Miyazaki, to name only a few. The animator creates 12 to 24 separate drawings on individual sheets of paper and then photographs them in sequence. When the photographs are played back in rapid succession, the illusion of movement is given. Today’s most popular 2D productions include The Simpsons, Family Guy, SpongeBob SquarePants, as well as classic Disney features and the growing cult following of Japanese Anime.

The CG medium began coming to the forefront in the 1980s through special effects for live-action films such as Tron and The Last Starfighter, which led to the breakthroughs by people like John Lasseter, who directed the first computer animation feature Toy Story at Pixar. Animators work with 3D character models that exist inside the virtual reality of a software program. The process is similar to stop-motion in that the models can be moved into positions like a real puppet, and the computer moves the model from one position to the next. All of the lighting and textures are artificially created by the computer, striving to duplicate reality. The medium has become today’s most popular, used to create fully CG films like Shrek, Madagascar, and The Incredibles, as well as more realistic characters that share the screen with live actors in films like Lord of the Rings. Video games have also become a groundbreaking vehicle for CG effects and animation.

If you visit any Web forum where animators or animation fans post messages about their craft, you are bound to find a few threads that start with a discussion about 2D versus CG, or CG versus stop-motion, and many pages of heated responses ensue. Few things get some classically trained animators riled up more than how much they believe CG animation pales in comparison to the “old-school” ways of doing things. The reality is that no technique is better than any other. All mediums shine in their own way, and, if done right, they can all be an incredible experience to watch. What it all really comes down to is the story, design, and characters, and how well they are complemented by the medium in which they are created. A film’s success does not ride on what medium is used, but rather the effectiveness of the story and the relationships between the characters.

Stop-motion animation has many differences and quirks compared to other mediums that give it its special charm, as well as a few advantages and disadvantages. One example is that in 2D animation, anything can happen because it can simply be drawn. Characters’ faces can be more expressive, and anything can squash, stretch, or change shape. Think of the outrageous gags in a Tex Avery cartoon, such as Red Hot Riding Hood (1943), or the exaggerated surrealism of shows like Ren & Stimpy. These effects would be extremely difficult to achieve in stop-motion, although some slightly successful attempts have been made. CG animation is starting to move more in this direction as the software develops, but it still lacks the linear quality given to the complete freedom that 2D offers.

Anything the mind can conceive is simply put on paper, and the most impossible gags can happen. Stop-motion has more limitations in terms of what kinds of movements can be created, and there is also the issue of gravity, which other mediums do not contend with at all. A puppet cannot float in midair on-screen unless something holds it up, but a character on paper or in virtual reality simply needs to be drawn or rendered that way. One major advantage that stop-motion has over other mediums, however, is the fact that issues of perspective and lighting are automatically solved, in that they already exist in real life and don’t have to be replicated. Stop-motion uses real lights and real depth of field, with puppets creating their own shadows. In other mediums, especially 2D, this effect must be painstakingly created by the artists who are importing the real world into their work.

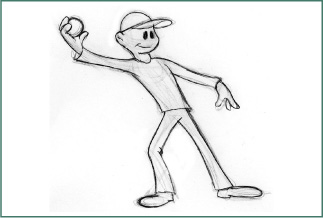

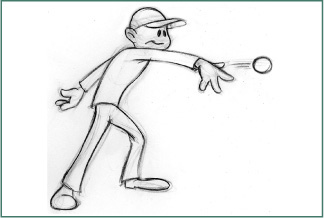

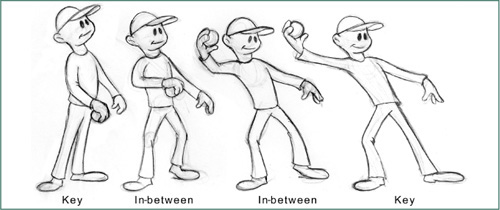

In 2D animation, there are two methods that can be used in terms of the order of drawings that are created: pose-to-pose and straight-ahead. In pose-to-pose, the animator determines which poses of the action are most important and draws only those poses first.

For example, if you are animating a baseball pitcher throwing a ball, the main elements of the action would be the first initial pose (see Figure 1.1), the windup, or anticipation (see Figure 1.2), and the pitch (see Figure 1.3). These poses are called the key drawings and are drawn first. Then, once the timing of these keys has been determined, the drawings that smooth out the action need to be created to fill in the frames between them. These secondary drawings are called “in-betweens” (see Figure 1.4).

Then all of the keys and in-between drawings are put together in sequence. Computer animators will simply position their character models into the key positions they desire, and the computer will create the in-betweens for them.

Straight-ahead animation is achieved by starting with the first drawing and then creating each sequential drawing in the order it will be projected to the viewer. This method is rarely used for animating an entire character in 2D. Since the character must appear to be a solid, three-dimensional being, it is extremely difficult to keep the volumes consistent when animating straight-ahead. It is far easier to plan out the keys and go back to fill in the in-betweens. However, in stop-motion, it is exactly the opposite. In fact, straight-ahead is the only way stop-motion can be animated. There are no “keys” or “in-betweens”; each position leads to another, in the proper sequence. Many stop-motion animators like working this way, because it can sometimes leave room for spontaneity and last-minute inspirations for the scene that may pop into their heads while immersed in this slow-motion acting process, whether it be moving a puppet, prop, or vehicle (as in Figure 1.5).

In a 2D animation studio, most often the in-betweens will be created by a different artist than the animator who creates the keys. An in-betweener is a typical entry-level position that most key animators start off in before working their way up. So, generally, in this method, the sequential drawings are created out of order by different artists and put into the proper order for shooting. If you watch the credits of a 2D animation feature, such as The Lion King, you will notice that there is an entire team of artists assigned to each character. These studio employees, whether they be key animators or in-betweeners, will draw only one particular character for the entire duration of production. There are no key animators or in-betweeners in a stop-motion studio, because each frame is created by a single animator working on each sequence. When watching a 2D animation sequence, you are watching a performance guided by one supervising animator but created collectively by a team, with each frame initially drawn by a different hand. A stop-motion sequence is a performance created individually by a lone actor baring his or her soul through the puppet (as in Figure 1.6). It’s also more common for a stop-motion animator to work on several characters at different points in the film, rather than sticking to only one character.

One of the biggest advantages of stop-motion over the other mediums is the fact that in stop-motion, after the puppets and sets are built and the animation is shot, it’s done! Other than editing, adding music and sound effects, and possibly compositing, no more procedures are required. In 2D animation, there are many more steps to the final process. The initial animation is usually done with very rough drawings, which then need to be cleaned up with finer line quality. Then the drawings need to be scanned, colored in with the computer, have lighting effects and shadows added, and composited into the background. The process can take much longer and require more manpower to complete. CG animation has a similar process of an animated scene going through subsequent departments for lighting, texturing, and final rendering. Despite this advantage of stop-motion, the other side of the coin is that because a stop-motion sequence is a one-time performance, everything has to be planned in advance that much more carefully. In 2D animation, if any changes to the timing or drawings are needed, the animator can simply add or remove drawings or erase any mistakes and redraw them. CG animation can also be tweaked over and over again until it’s perfect, and the animator has exhausted every pushed pose and nuance he can dream of to strengthen the animation. That’s where CG works as sort of a bridge technique; it has the appearance of stop-motion with the control factor of 2D. It’s really an extension of traditional stop-motion, with the ability to do things that stop-motion can’t do as easily in terms of flexible expressions and effects.

All of these comparisons really boil down to the fact that all animation, regardless of the medium, is time consuming, and each medium has its own pros and cons. Stop-motion in particular is a very specialized technique, and part of the reason it’s not seen as much is because of the disadvantages it has in comparison to 2D or CG. It probably requires more patience and perseverance than any other medium, and it may not be a technique that every animator can master. It takes a certain kind of eccentricity to totally pursue it, because it’s also the most physically taxing method. But it’s always been around and will never go away, because, as I mentioned in the Introduction, people still love it!

If any topic deserves an entire volume of books unto itself, the history of stop-motion animation is definitely one of them. So many different artists have contributed to the stop-motion medium, and many of them are obscure and overlooked. While some have six degrees of separation between them, others have no historical connections to each other. It’s a difficult task to condense the entire story of stop-motion animation into a few pages, so I will just focus on some of the artists, films, and trends that have had the most impact, been overlooked by most historians, or serve as the best reference material for this book. The main reason I believe the history of stop-motion needs to be mentioned here is that nobody can expect to move forward in any art form or trade without understanding what has come before him. The past 100 years have created many amazing ideas that should serve as the ultimate inspiration for any stop-motion animator, not only in watching the films, but in knowing about the artists who created them. Knowing your history is so important, because it prevents you from repeating some of the trials and misfortunes of artists past, enhances your own stop-motion work, and should encourage you to try new techniques. Once you become a stop-motion animator, you are then part of its history. Plus, you get to impress your animation colleagues because you know who artists like Starewitch and Svankmeyer are.

Animation existed before movies were invented. In the late 1800s, there was a renaissance of attempts to create the illusion of movement with inventions that would rapidly display a sequence of drawings before the viewer’s eye. The zoetrope (see Figure 1.7) was one such example, where sequential animation drawings were placed inside a drum with equally spaced slits along the outside of the drum. By your spinning the drum and looking directly through it, the drawings would appear to move.

The whole concept behind animation relies on a phenomenon called the “persistence of vision,” which basically means that the retina of the eye will retain any image for a brief moment of time until replaced by another image, thus creating an illusion of movement, rather than individual static images. Edward Muybridge started applying this discovery to still photographs by photographing human and animal movements with a row of cameras that each took one successive picture to create a series of separate “frames.” Before long, other inventors developed ways to package this process into one camera. In 1882, Etienne Jules Marey of France developed a camera that could take 12 successive pictures per second. Thomas Edison went a step further and developed the first Kinetograph movie camera in 1890. These earliest cameras were operated by a crank that would run the film through while the shutter opened and closed once for each turn of the crank, creating a series of static images that would appear to move when developed and projected.

The discovery of stop-motion animation happened primarily by accident. Accounts differ as to the first actual person to create the “mistake” that led to this art form. According to legend, French stage magician and amateur filmmaker George Melies was shooting a street scene when the film got stuck in the camera gate. During the process of fixing the problem, life continued on as normal on the street and, once the camera was fixed, Melies continued filming where he left off. In the final film, he was amazed to find that pedestrians and vehicles had instantly transformed, or jumped, from one side of the street to another. This experiment led to the idea of deliberately stopping the camera, changing elements of the scene, and starting it up again to create illusions of transformation: people vanishing into thin air, turning into mannequins, or men turning into women and vice versa. The “stopping” of the camera to manipulate objects between captured frames apparently inspired the actual term stop-motion still used today. Melies continued experimenting with this technique and incorporating his “trick films” into his magic stage shows. His most famous film using the technique was 1902’s A Trip to the Moon, the first science-fiction effects picture in film history. Meanwhile, in America, Thomas Edison was making similar film experiments such as Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots (1895), in which a real actress was filmed in a guillotine and replaced with a dummy while the camera was not rolling, giving the final illusion of being decapitated. In an age before the Internet or any other kind of instant global communication, it is interesting that similar trick film experiments were happening almost simultaneously in different corners of the world.

The first known American film to use animated puppets was The Humpty Dumpty Circus (1898) by Albert E. Smith and J. Stuart Blackton (see Figure 1.8). Blackton continued experimenting with stop-motion puppets, objects, and clay animation techniques in Fun in a Bakery Shop (1902), The Haunted Hotel (1907), and Princess Nicotine (1909), and he also created the first animated film involving sequential drawings on a chalkboard, Humorous Phases of Funny Faces (1906). Other stop-motion films were created by filmmakers who remain mysteriously anonymous today, such as the delightful Automatic Moving Company (1912), which featured pieces of furniture sliding out of a moving truck, up a set of apartment stairs, and magically setting themselves up inside. The extensive use of clay as an animation medium made its debut in a series of shorts called Miracles in Mud from a series entitled Reel of Knowledge (see Figure 1.9) Back in France, inspired by the French premieres of Blackton’s films, filmmaker Emile Cohl made similar films with animated objects, creating shapes on a tabletop, such as The Bewitched Matches (1906; see Figure 1.10).

These early forays into the stop-motion technique amazed audiences during the time they were made, but by the late 1920s, their novelty was overshadowed in America by the animated 2D cartoons of Winsor McCay, Earl Hurd, and Walt Disney. The Fleischer brothers in New York were more experimental in a few early attempts to combine 2D animation with clay animation. The Koko the Clown short Modeling (1921) featured the title character escaping from his drawing board and throwing clay at the artists in the studio.

Sadly, many of these early films do not exist today, because early film stock was a perishable material unless preserved with the proper care. Early films made before the advent of celluloid were also printed on nitrate, which is highly flammable and was known to burn down entire movie theaters by getting stuck in the projector! Thanks to the efforts of film collectors and preservation societies, a precious few of the earliest stop-motion films remain intact. Occasionally, lost films continue to turn up in the most unusual ways. In the 1960s, one such body of stop-motion work was discovered unexpectedly in the projection room of an old French movie theater. After much investigation, these short films were found to be made by Charley Bowers, an American filmmaker who had since been all but forgotten. Bowers had worked as a 2D animator, writer, and director on the famous Mutt and Jeff cartoons in the 19-teens and ’20s, and had also created a series of slapstick live-action shorts, often starring himself, in the tradition of his contemporaries Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd. The difference was that his films also contained inspired sequences of surreal stop-motion animation effects involving wacky inventions and repeated gags of cars and animals hatching out of eggs.

Later films produced on into the 1930s include the bizarre cult favorite It’s a Bird (1930; see Figure 1.11) and the strange promotional film Pete Roleum and his Cousins (1939), which was commissioned and directed by Joseph Losey. The rediscovery of these lost gems of surrealistic filmmaking led to screenings at the Annecy Festival in the 1970s and a DVD release by Lobster Films in 2004. To watch these films and ponder the fact that Bowers had been neglected by the history books until now, one has to wonder if they had an influence on the works of Tex Avery or Dr. Seuss, as there are many striking similarities in designs, ideas, and weird humor. Bowers’ films are full of ingenious techniques that could make for some fantastic stop-motion effects using today’s updated technology.

Another technique that is a close cousin of three-dimensional stop-motion animation is that of 2D cut-out animation, which also had its genesis during the early 1900s. In this method, flat 2D “puppets” would be manipulated under a rostrum camera pointing down on a tabletop. The cut-outs could be jointed with strings or tiny paper fasteners so that they could be moved frame by frame in the same method as traditional stop-motion. The technique originated largely in France by Emile Cohl with short experimental films such as The Neo-Impressionist Painter (1910; see Figure 1.12), and, in Germany, Lotte Reiniger used the technique to bring the traditional Asian art of shadow puppets to the movie screen. Due to the limited scope of movement that cut-out animation provides, it never caught on as an extremely widely used medium. Most of the cut-out films made through the years have an offbeat surreal quality to them, where part of their charm is in the stiff graphic style they exude.

In the 1940s, the Ottawa Film Board in Canada made several cut-out films, including a strange promotional spot called Three Blind Mice (1945) where cut-out mice demonstrate the hazards of the average workplace by going through a series of repeated injuries. Through the 1960s and ’70s, cut-out animation really came to the forefront in the UK with the surreal anarchy of Bob Godfrey’s Do-It-Yourself Cartoon Kit (1961) and Terry Gilliam’s cartoons from Monty Python’s Flying Circus (1969–1983). The original films that would become Trey Parker and Matt Stone’s South Park series were made in cut-out animation, but the series itself is done on the computer, which is now carrying on the cut-out look with other similar series. The current trend of Flash animation for Web and television is very much a modern extension of the 2D stop-motion techniques that have been around since the very beginning.

From an early point in stop-motion’s history, there are two timelines that represent two major uses for the medium. One of these timelines came to an abrupt end in the mid-’90s, and the other timeline is still moving into the future. The former timeline has its origins in the U.S., where stop-motion began being used as a special effect for movie sequences that involved scenes where an animated creature or vehicle needed to be merged with live action. Many of the early stop-motion films used this technique, but the effect was usually with puppets or objects that were either the same size or smaller than the actors. In the genre of what I like to call “creature effects” using stop-motion, the puppets would be approximately 12–18 inches tall, but on the screen they would appear to be towering over the live actors with whom they shared the screen. The director’s vision of giant creatures or spaceships attacking cities or battling heroes could be realized in this method.

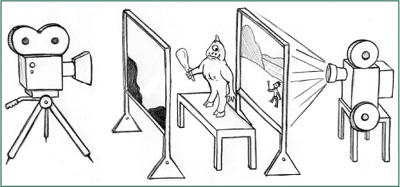

Several different film techniques were employed to create this illusion. One way was to create a matte shot. By masking out certain portions of the set in front of the camera with a black card, filmmakers could shoot live action footage that fit outside the masked-out area. The black card allowed no light to be exposed onto the film. The film was then wound back to the exact starting frame of the scene, and the black matte was reversed so that the previously unexposed area was now visible and the previously filmed area was masked out. Then the animator could move his puppets within this area, and when the film was developed, everything would blend together into the final image. The only limitation offered by this method was that the live-action and animated elements were not allowed to cross the line of the matte; otherwise, they would be cut off. Other methods included small screens built into miniature sets with live-action images projected into them, and using an optical printer to marry certain elements together to create a seamless composite.

Another popular method was that of front or rear projection. This technique was often used in live-action films to create the illusion of actors driving a car down the road. A stationary car sits in front of a screen with a projector behind it, projecting previously shot footage of a moving road. This technique was invented to avoid the expensive process of shooting the actors in a moving car.

To use this method in stop-motion (see Figure 1.13), a miniature set would be placed in front of a projection screen. The rear projector would then project one frame at a time of the previously shot live-action footage, and the puppets animated on the set to match it. If the shot required any foreground elements that the puppet must move behind, these elements would also be matted into the shot with black cards on a glass plate. Careful attention had to be paid to the lighting to make sure the puppet blended in seamlessly with the projected background and foreground.

The pioneer for this genre of stop-motion filmmaking in the U.S. was San Francisco native Willis O’Brien, who first experimented with stop-motion while working in a decorator’s shop. O’Brien developed intricate armatures that could form the skeleton for his puppet figures and hold each position they were moved into. His further experiments led him to begin making puppets with a foam rubber skin covering a metal ball-and-socket armature. It was around this time that many of the first dinosaur skeletons were being dug up and displayed in museums, awakening the public’s imagination to these giant beasts of the past. O’Brien picked up on this trend and created short films with miniature dinosaur puppets. His first films, though crude by today’s standards, were authentic enough to convince audiences that they were “lost footage” of real dinosaurs!

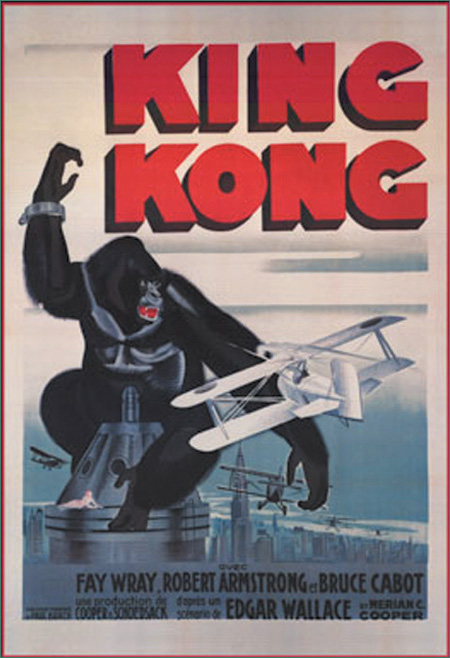

His short dinosaur film Ghost of Slumber Mountain (see Figure 1.14) in 1919 led to his groundbreaking work on The Lost World feature film, released in 1925. The film had a modest success due to O’Brien’s masterful work, not only animating the puppets but supervising the construction of miniature sets and camera tricks. In 1931, O’Brien started an ambitious project called Creation, which was never completed but served as a test reel for the effects that could be done for an upcoming project by RKO. That project was Merian C. Cooper’s King Kong, finally released in 1933 (see Figure 1.15). King Kong was about a band of American filmmakers who find a giant gorilla named Kong on a native island and bring it back to New York with them. Kong was masterfully animated by O’Brien and composited into each shot to blend with the live actors. The impact that King Kong would have on the movie-going public and the medium of stop-motion animation can hardly be put into words. Today, hundreds of films are released every year with mind-blowing effects, so it’s hard for us to imagine what a big deal this film really was. Released during the Great Depression, it was pure escapist entertainment in the tradition of the best adventure film and radio serials of its day, and it gave its audience a welcome respite from their daily trials. One classic scene after another kept viewers riveted, from the violent duel between Kong and a Tyrannosaurus Rex (probably included due to O’Brien being a boxing fan) to the climactic face-off on top of the Empire State Building. But even more than the action scenes, King Kong’s true breakthrough in America for the medium of stop-motion was the raw emotion that O’Brien displayed through the character of Kong. For the first time, puppet animation for American audiences was not just a novelty of moving objects but a true form of acting. In the final moments before his death, Kong’s facial expressions and body language are just as tragic and powerful as any human performance on stage or screen.

One of the many audience members King Kong changed forever was Ray Harryhausen. After seeing the film at age 13, he immediately began learning how to make stop-motion films of his own, and one of his first jobs was at George Pal’s studio working on the Puppetoon shorts. Harryhausen eventually got to work with his mentor O’Brien on the 1949 film Mighty Joe Young. Already in those days, he proved himself as an excellent animator and innovator. He is now rightfully credited as a legend in the stop-motion field and has been the inspiration for practically everyone working in the industry ever since.

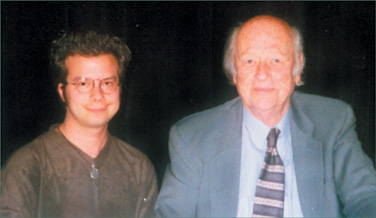

I had the rare privilege to meet Ray Harryhausen briefly in 2001 at the Vancouver Effects & Animation Festival (see Figure 1.16). When I told him I was a stop-motion animator and instructor, he remarked, “Ah, you’re still young! You haven’t pulled your hair out yet!” I found him to be an extremely friendly and generous man.

Harryhausen carried O’Brien’s techniques to even greater heights. Although his early films featured cartoon-style fairy tales and fables, Harryhausen is most famous for the creature effects he created for a series of live-action adventure films from the 1950s to 1980s, marketed as a film technique called Dynamation. He also created his own puppets (see Figure 1.17).

Figure 1.17. Some of Ray Harryhausen’s puppet creations. From left to right: Skeleton from Jason and the Argonauts, Medusa from Clash of the Titans, and the Bowhead Statue from The Golden Voyage of Sinbad.

Harryhausen worked closely with the directors, writers, and designers, and his films started in the genre of monsters attacking big cities (such as 1953’s Beast from 20,000 Fathoms) but eventually came to be based on hero myths and legends of ancient civilizations. His first color film was 1958’s 7th Voyage of Sinbad, the first in an eventual Sinbad trilogy, which featured fantastic creatures such as the Cyclops and a sword-wielding skeleton. The skeleton returned, along with six others, in the climactic battle scene from 1963’s Jason and the Argonauts. That scene is among Harryhausen’s most famous work, and it is still studied by filmmakers and animators today. (If you have never seen this sequence, go find it and prepare to be amazed!) Each skeleton engaging in a sword fight with the live-action Argonauts had to be animated at the same time to ensure that each frame matched up perfectly with the choreographed live-action footage. Harryhausen had to keep track of which puppets were moving forward and backward, using only his own memory and notes on paper, without the use of frame grabbers or video monitors. The results are unbelievably stunning, not only in the smooth animation, but in the editing as well. What is most interesting about Harryhausen’s work today is that the sequences are like a kind of fanciful cinematic theater in the way they are staged. Since the technology did not allow the camera to move much, the action relied more on the editing and the relationships between the puppets and actors, versus today’s films, which tend to stress too much jarring camera movement. And again, it’s important to remember the impact these films had in a time when there was less competition for entertainment than there is today.

Harryhausen’s last film before his retirement was Clash of the Titans (1981), which included his tour de force sequence of Medusa the Gorgon stalking the Greek hero Perseus. Assisting Harryhausen in creating some of the other animation shots were some of the rising stop-motion animators and effects artists of the industry, such as Jim Danforth. Danforth had started his career in stop-motion at a young age on the TV series Davey and Goliath and moved on to animate on feature films such as 7 Faces of Dr. Lao (1964), When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth (1970), and dozens more. On some of these films, he had worked with another talented animator named Dave Allen, who went on to become another of the industry’s most dedicated stop-motion professionals. In addition to being on the crew of several films through the ’70s and ’80s, Allen spent 20 years working on an ambitious live-action/stop-motion feature called The Primevals, which unfortunately remains unfinished due to his death from cancer in 1999. Other stop-motion animators who had worked with Danforth and Allen who continued to make their mark on the industry included folks like Randall William Cook and Jim Aupperle, who have now successfully transitioned into today’s CG visual effects field.

Another influential stop-motion artist is Phil Tippett. Tippett first began animating on his own homemade films and a few B movies before joining the effects team on Star Wars in 1977. The phenomenal success of that film paved the way for more groundbreaking work with George Lucas’ Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) studio well into the new decade of the 1980s. While creating stop-motion effects for The Empire Strikes Back (1980), Tippett came up with a technique that would attempt to reduce the jerky movement of previous works. In studying live-action film frame by frame, animators noticed that in some frames, the motion would be blurred as a result of a slightly longer shutter exposure. Tippett devised a way in which his puppets could be rigged with a computerized armature that would move the puppet slightly while certain frames were being exposed, resulting in a motion blur that would have a closer resemblance to real live movement. The full results were utilized for the 1981 fantasy picture Dragonslayer, in Tippett’s animation of the dragon Vermithrax. In several amazing shots of Vermithrax crawling through her cave, the fluid movement created by the motion blur has a similar appearance to today’s CGI effects, which didn’t exist at that time. This motion blur technique was coined “go-motion,” and it was improved upon at ILM in subsequent features such as Return of the Jedi (1983) and Willow (1988). The continued influence of O’Brien, Harryhausen, and Tippett on Hollywood gave us a great variety of stop-motion effects on through the ’80s, appearing in films such as Caveman (1981), Ghostbusters (1984), Evil Dead II, The Gate, and Nightmare on Elm Street 3 (all 1987), to name only a few. It is because of this era of filmmaking, and the eras that had come before, that we now have the CG effects being created today. Tippett himself was involved with one of the films that ultimately started this digital transition.

In the early ’90s, preproduction began on Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park. With Tippett on his effects team, early tests were created to animate realistic dinosaurs using the traditional go-motion technique. However, there was much experimentation going on at ILM with computer animation and the possibilities offered to them by continually advanced technology. James Cameron’s films The Abyss (1989) and Terminator 2 (1991) were among the first films to begin using this new technology to its fullest potential. A team led by effects artist Dennis Muren began a series of tests to prove to Spielberg that computer animation could be used to achieve better results than go-motion. The final test results were so authentic that Tippett’s verbal reaction was “I think I’m extinct.” Impressed by the fluid realism offered by this new technology, Spielberg made the decision to replace the go-motion dinosaurs with CGI throughout the entire film. Tippett’s team of puppet animators, who were so used to creating their effects by hand, were beginning to feel the pinch of this new technology that was threatening to pull the plug on their craft. But Tippett, due to his expertise in animal behavior and movement, was still able to use his skills to aid the computer animators. His shop actually devised a special armature that was encoded with wires extending from its joints into the computer. Nicknamed the D.I.D. (Dinosaur Input Device), it allowed the animators to move a physical puppet into position as they were accustomed to, and have their movements translated into a 3D computer model. This model could then be mapped with the proper lighting and textures needed to blend it into the live-action footage. The sequences with the T-Rex first emerging from its pen, and the Velociraptors in the kitchen, were actually stop-motion animation that had been fed into the computer. The stop-motion dinosaur movie genre that started with The Lost World in 1925 had come full circle in 1993 with the release of Jurassic Park, and continued into its 1998 sequel, also ironically titled The Lost World.

The success of Jurassic Park and its groundbreaking effects heralded the end of traditional stop-motion puppets as filmed by O’Brien and his protégés for the use of realistic creature effects in mainstream Hollywood movies. Today traditional stop-motion is used only for independent projects or B-movies intended to hark back to these old films. The photo-realism created by CGI has enhanced the expectations of modern audiences to the point that any attempt to animate foam rubber puppets on miniature sets would look crude by comparison. It’s rather ironic that today’s “realism” has proven to be better achieved through computer models, which lack the realism of an actual physical puppet. Some purists may argue that there is a coldness to CGI that does not warrant the same sense of texture derived from actual materials. Perhaps the improvements made in digital compositing and the technical smoothness of stop-motion animation will warrant a renaissance for creature effects in the future, but only time and the right people, story, and budget will tell. The important thing to remember is that today’s films owe their very existence to the special effects of the past, and much can still be learned from them. While Jurassic Park may have faded out this timeline of stop-motion’s history in 1993 (not to mention Army of Darkness adding a coda of final B-movie tribute to the medium), that very same year saw the release of two films that would carry the medium forward in a huge transcendent leap: Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas and Nick Park’s The Wrong Trousers. In both of these films, the animated puppets did not share the screen with live actors, but rather existed in their own world, representing the latter of the two timelines I mentioned previously. The genre of stop-motion in films that are exclusively animated is still alive and well today and has had a vibrant history of its own.

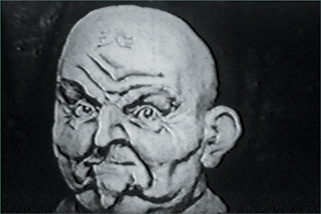

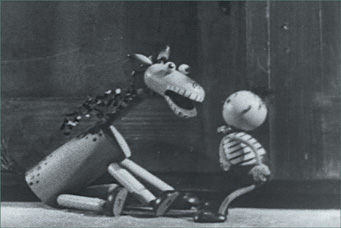

While Willis O’Brien was busy pioneering the American method of using stop-motion for creature effects, on the other side of the globe another style of the medium was being developed. Ladislas Starewitch, born 1882 in Moscow to Polish–Lithuanian parents, was responsible for changing stop-motion from a technical novelty to a storytelling art form, much like Walt Disney did for 2D cartoon animation. Starewitch grew up with a keen interest in art and entomology, collecting and studying all varieties of insects. While working as a filmmaker at the Khanzhonkov Studio in Russia, he began making experimental documentaries about live beetles. His early attempts at making the beetles do anything he wanted under hot lights proved to be frustrating, so, inspired by Emile Cohl’s film Bewitched Matchsticks, he rigged some embalmed beetles with wires and animated them. The stop-motion technique applied to real insects had never been seen in Russia, and many audiences thought that the beetles had been trained to “act” by some odd form of science. In one of his most humorous films, Revenge of the Cameraman (1912; see Figure 1.18), Starewitch told a silent tale of adultery between a group of suburban insects. This was one of the earliest known attempts to actually tell a real story exclusively with stop-motion puppets.

Figure 1.18. Ladislas Starewitch’s film Revenge of the Cameraman. (Copyright L.B. Martin-Starewitch.)

The success of these insect films led Starewitch to move on to more detailed puppets made of metal armatures, wood, felt, and chamois leather. Due to the growth of the Communist regime after World War I, he moved to Paris in 1920 and began producing two to three films a year. His stories were inspired by Eastern European folklore and fairy tales, ranging from gentle children’s stories like Voice of the Nightingale (1923; Hugo Rosenfield Prize winner 1925) to bizarre horror/fantasy films like Fern Flowers (1950). The level of detail and emotion that Starewitch was able to inject into his characters was outstanding for the time the films were made, especially those with several different puppet characters, such as The Old Lion (1932). This film featured a flying elephant nine years before Disney created Dumbo (1941), and his 1928 film The Magic Clock featured his own daughter escaping the hand of a giant, similar to scenes from King Kong. These scenes are just a few examples of how Starewitch was very much ahead of his time and had an impact on other filmmakers. Many of his films also featured a motion blur technique for certain quick puppet movements, which may have been created by smearing Vaseline on a plate of glass in front of the camera, or by using wires.

One of Starewitch’s most famous and elaborate films was The Mascot (see Figure 1.19), which was released in 1933, the same year as King Kong. Framed by live-action sequences, The Mascot tells the story of a small dog toy that goes on a quest to find an orange for a hungry little girl and ends up at a party thrown by the devil and his guest list of grotesque characters. The macabre imagery of The Nightmare Before Christmas and modern tales of toys coming to life (such as Raggedy Ann or Toy Story) could certainly have been influenced by The Mascot and other films by this creative storyteller. Many of Starewitch’s films are lost in the annals of history, but enough of them remain to inspire us today.

While Starewitch’s filmmaking career flourished in France, there began another renaissance in stop-motion that originated in Czechoslovakia. Czechoslovakia has always had a long tradition of storytelling through live puppetry, which carried over into film once the stop-motion technique had gotten around. The Czech style of puppet film differs from the more naturalistic styles chosen by Starewitch and O’Brien, with one example being the use of the face. Since Czech films were in many ways an extension of traditional puppet theater, faces would remain static throughout, with the acting dependent on the movement of the body. It is the way the puppet moves that tells us how he is feeling, despite the unchanging nature of his face. Live puppet theater relied on this technique for centuries, as large audiences would need to be able to read the puppets’ emotions even from the farthest seat. Cinema brought the puppets closer to the audience, so more intricate ways to depict realistic facial expressions could now be explored by puppet filmmakers. Nevertheless, most Czech puppet films put more emphasis on a lyrical quality based on body language combined with music and story.

One of the Czech movement’s earliest pioneers was female animator Hermina Tyrlova, who made a series of films at Ziln Studios. Starting with commercials and trick films in the 1920s, she became known for fairy-tale fables such as Ferda the Ant (1944) and the anti-Nazi propaganda short Revolt of the Toys (1945, released in 1947, well after the war; see Figure 1.20), and continued to make films aimed at children well into the 1970s. Tyrlova collaborated on a film called Christmas Dream in 1946 with another influential Czech animator, Karel Zeman, who went on to create fanciful films combining puppets with live-action and other special effects, including The Fabulous World of Jules Verne (1958).

While Tyrlova’s career in puppet films was just beginning, an illustrator named Jiri Trnka was creating 2D cel animation and would eventually transition into puppet films himself. Trnka became one of the most prolific Czech animators and had a major influence on the stop-motion medium. In 1946, he opened his own puppet film studio, which became a training ground for a whole legion of Czech animators. Trnka’s own films were based largely on local folktales and Czech customs. Many of them had a paradoxical reaction from the Communist government, who appreciated the films and supported them financially, but at the same time tried to dictate their subject matter and banned those they didn’t agree with. Several films, such as Archangel Gabriel and Lady Goose (1964), were rejected as church propaganda. Trnka wanted not only to explore religious imagery, but expand the subjects of his films beyond Czech legend and history, adapting tales from Spain and Shakespeare. His attempts to do so were met with mixed reactions from the public, as was his insistence on creating beautiful works of art while neglecting to appeal to the common interests of most audiences. The frustrations that Trnka endured throughout his career are important to study further, as there will always be a conflict in the animation industry, not necessarily between art and government in most societies now, but between art and business. Artists working in a large studio environment will often find themselves succumbing to the pressures of a corporate authority who doesn’t know anything about art yet will praise the artists when the product makes money. Trnka’s last film, The Hand (1965), was a metaphorical summary of his career and struggle to create art within a dictatorship government. The central puppet character is an artist who is constantly forced by a giant intruding hand to make sculptures of only the hand. The artist stubbornly refuses until the hand imprisons him and ultimately causes his death, only to then honor him with a state funeral.

The Hand is a fitting tribute to one of stop-motion’s great artists, as is the influence that Trnka passed on to many other filmmakers who studied with him, among them Jiri Barta, Vlasta Pospisilova, Bretislav Pojar, and Jan Svankmeyer. Svankmeyer is one of the most well-known animators from the Trnka tradition, and his films go beyond the traditional Czech puppet style into some of the most bizarre imagery ever put on screen. Many of his films are based on nightmares and dream states, often combining live action with puppets and animated found objects: toy dolls, dead animals, meat, food. Anything is possible in a Svankmeyer film, usually exploring dark topics and political commentaries very common to Czech art. His most well-known work is probably his 1988 live-action/stop-motion feature Alice, based on Lewis Carroll’s legendary story but decidedly much different and more disturbing than any other version. The influence of his films is most prominent in the films by two brothers from Philadelphia known as the Brothers Quay (Stephen and Timothy), who started their career in 1979. They produced their most famous works in London, creating nonlinear dream-state films using found objects, dolls, and puppets in decayed antique sets. The dark imagery of the Brothers Quay has had a profound influence on many contemporary rock videos by Tool, Nine Inch Nails, and other groups, so even though most Czech films of this genre may be unknown to modern American audiences, their mark has certainly found their way into unexpected areas of pop culture.

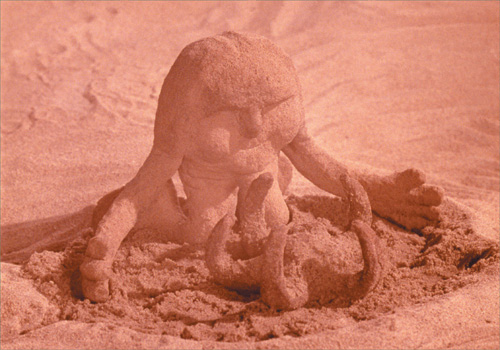

The Trnka studio has also been a haven for stop-motion filmmakers from other countries, such as Kihachiro Kawamoto from Japan, who combined the traditional Czech style with the popular Japanese Bunraku puppet techniques. Co Hoedeman, an animator from the Netherlands, immigrated to Canada and studied briefly with Trnka in Czechoslovakia in 1970. He then returned to Canada to make puppet films for the National Film Board and made many films based on Inuit legends, such as The Owl and the Lemming (1971). In 1977, Hoedeman made the Oscar-winning short The Sand Castle (see Figure 1.21) and since then has had a successful career making films about societal and environmental issues, as well as series for children.

Hoedeman is a rare modern example of a kind of filmmaker who has taken inspiration from European traditions of filmmaking and brought them to be produced in North America. Through the National Film Board, Canada has had a more similar history to Europe in regards to government sponsorship for experimental filmmaking for the sake of artistic exploration through film. Historically, the idea of stop-motion films intended for theatrical distribution has mostly thrived in Europe. Part of the reason for this is the strong tradition of puppet theater dating back to even the Middle Ages, including the popular Punch and Judy traveling shows. In America, the early experimental days of trick films developed into an industry, once the medium began being used for storytelling and entertainment. Film distribution became a contractual obligation to produce series of regular film packages in a method called block-booking. Theaters would purchase films from studios in a specific packaged format, which included newsreels, live-action short subjects, and animated shorts along with a feature film. The quick turnaround for these film packages meant that the animated content had to be delivered at a faster and cheaper rate, and cel animation proved to be a more convenient medium for this assembly-line approach to distribution. Thus, stop-motion films created by Americans took a different route into the realm of special effects for films like King Kong. Europe did not have this block-booking method for film distribution, so there the focus was more on creating films for the sake of creating art, telling stories, and often making societal or political statements for public enlightenment.

An influential stop-motion pioneer who took this filmmaking tradition from Europe to America was Hungarian-born George Pal. Pal set up his first cartoon studio in Prague in 1933, and he started making films with puppets because he couldn’t find any cameras that were designed for shooting 2D cartoon animation. His early commercial projects eventually led him to set up shop in Holland, where he continued to make animated ads and short subjects. Pal’s breakthrough technique was the use of “replacement animation.” With this method, instead of building one puppet and manipulating it, several different versions of a puppet would be produced, each one slightly different from the next. The animation, in a sense, was created by the individual puppets themselves, and they would simply be replaced one at a time in front of the camera. Oftentimes, the animation would be done on paper and then 3D wooden pieces would be carved to match the drawings, which allowed for fluid 2D-style squash and stretch effects impossible to achieve with just a single puppet. Up to 100 different replacement pieces would often be needed to create the wide range of movements for some characters. The unique visual style was appealing to the audience, and when Philips Radio in America saw them, they began sponsoring Pal’s films. In 1939, when the Nazis invaded Poland, George Pal took that as his cue to move to America, sign a deal with Paramount Studios, and set up the first puppet film studio in Hollywood, creating a series of theatrical shorts called Puppetoons (see Figure 1.22).

One of Pal’s best films, Tulips Shall Grow (1942), was an autobiographical sketch of the European Nazi attacks. World War II inspired many propaganda shorts made by animators, including Lou Bunin’s Bury the Axis, featuring puppet versions of Hitler, Mussolini, and Hirohito. Amidst the many films made in this style, Pal’s film stands out as very unique. A frolicking Dutch couple dance in front of a windmill, only to be invaded by an army of soldiers called “Screwballs.” The couple is separated during the chaos, and the male character seeks shelter in a nearby church. He prays for rain, which comes down and causes the metal soldiers to rust. The young lovers are reunited and continue to dance, leaving on a note of hope that “tulips shall always grow.” The optimistic nature of this film during a time of war was a signature style of Pal’s work. Another historically significant film of his was 1946’s John Henry and the Inky Poo, based on the American folktale of the legendary railroad worker. Most animated films of this period, including Pal’s own popular series about a young African-American boy named Jasper, depicted black characters as stereotypes and are considered politically incorrect by today’s standards. John Henry was one of the first animated films to portray African-American characters with dignity and respect and helped to move us away from the racist caricatures that were more common back then. As the costs for Puppetoons rose, their profits fell, as they were charming but unable to compete with the antics of 2D stars like Tom & Jerry. The best lesson from George Pal’s career for today’s filmmakers is that he picked up on upcoming trends and knew that theatrical short subjects would not always continue to be popular. Feature films were the best way for him to continue his film career, so he took the experience he gained from his Puppetoons and used it to create miniature models and special effects work for features. His work on films such as Destination Moon (1950), War of the Worlds (1953), and The Time Machine (1960) paved the way for miniature model effects used in films like Star Wars, so George Pal’s influence has extended even beyond the realm of the puppet film.

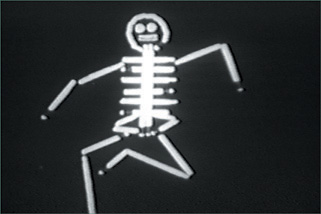

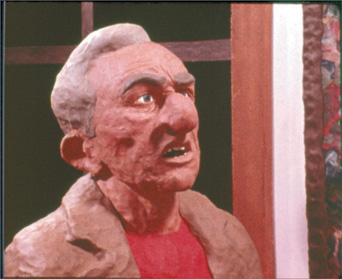

After World War II, as theatrical short films in America slowly became a rarity as part of feature film packages, they began being produced for television, schools, or the limited venues of specialized film or animation festivals around the world. Today, thanks to the popularity of film festivals, making short films exclusively in stop-motion is rather commonplace worldwide. The Academy Awards continued to honor animated short subjects with a special Oscar each year for “Best Animated Cartoon,” until the winning film in 1975 changed the award title to “Best Animated Short Film.” This was because the film was not a “cartoon” in the traditional sense, but the first stop-motion clay animation film to win the Oscar. The film was Closed Mondays by Will Vinton and Bob Gardiner (see Figure 1.23), made entirely in clay, about a drunk man who wanders into a closed art museum and watches the art come to life in surreal ways. In one scene, the man accidentally turns on a talking robot that proceeds to morph into random objects and then melt, to which the drunk man remarks “Blabbermouth computer!” (A hilarious and rather prophetic comment about modern technology!)

The breakthrough technique of Closed Mondays was the use of clay to achieve a realistic method for dialogue and detailed facial expressions never previously attempted in stop-motion. Riding on the success of his Oscar win, Vinton started his own studio in Portland, Oregon (Will Vinton Studios) and continued making short films with this technique, which he trademarked specifically as Claymation. The popularity of Vinton’s work is proven by the fact that the term “Claymation” has become so commonplace that it is often used to refer to stop-motion animation as a whole, including puppet films that do not use clay at all. Vinton assembled a team of talented artists and animators, including Barry Bruce, and perfected his clay craft with beautiful works such as Martin the Cobbler (1977), A Christmas Gift (1980), and The Great Cognito (1982).

Meanwhile, in the UK, a couple of schoolboys named Peter Lord and David Sproxton made some clay animation films that led to the founding of Aardman Animation Studios. Because the clay medium lent itself so well to subtlety in puppet dialogue, they started a series of films called Conversation Pieces in the 1970s, which were based on improvised interviews and recorded conversations. Several animators, such as Barry Purves and Richard Golezsowski, would eventually lend their talents to the Aardman studio to create a diversified range of styles for films made for BBC television and film festivals. The most significant recruit for Aardman was Nick Park, who was making a clay animation film at the National Film and Television School called A Grand Day Out, about a man named Wallace and his dog Gromit, and their trip to the moon. Aardman hired Park part-time to work on commercials while helping him finish his 30-minute film, which took 6 years to complete. Shortly afterward, in 1989, Park created his own version of the Conversation Pieces series, Creature Comforts, which took improvised dialogue about living conditions in England and put it in the mouths of zoo animals. The brilliant results made the 5-minute film a huge success and won Nick Park his first Oscar. Riding on the success of both Creature Comforts and A Grand Day Out, which also won several awards, Park began another half-hour film at Aardman starring Wallace & Gromit called The Wrong Trousers. It was a suspenseful tale involving a mysterious penguin, a jewel heist, and a pair of mechanical pants. It was another smash hit in its 1993 release, eventually making its rounds in festivals and public television screenings around the world. The Wrong Trousers and its 1995 follow-up A Close Shave both won Oscars again for Nick Park, putting him and his colleagues at Aardman on the map as one of the most successful stop-motion studios in the world.

Before the advent of television, there was a very little known method in the U.S. for watching films in the comfort of one’s own home. Kinex Studios in Hollywood produced a series of stop-motion shorts in the 1920s and ’30s for the Kodak Cinegraph company (see Figures 1.24 and 1.25). These films were not distributed to theaters, but rather to camera shops where customers could buy or rent them on 16mm film for home projection, much like video and DVD rental stores of today. Some of the known artists who worked on these bizarre Kinex shorts include John Burton and Orville Goldner.

Eventually the television became a standard in the average home, and the 1950s were the golden era of the television age. Broadcasters began showing theatrical animated films from the war era, and cheaply produced new cartoons using limited animation began a new trend for this new method of distribution. Suddenly there was a whole new venue for animated content, and stop-motion productions, though still few and far between compared to 2D cartoon shows, began making their mark on the popular culture. Before stop-motion puppets became popular on American television, they were preceded by close cousins of the puppet variety. Productions with hand puppets and marionettes, created by artists such as Bil Baird and Burr Tillstrom, started making their way from live stages to the TV screen. Muppet creator Jim Henson got his start in the 1950s as well, with his first TV series, Sam and Friends. It was then on the Howdy Doody Show, a popular children’s puppet program, that TV’s first stop-motion star Gumby emerged in 1956.

The genesis of Gumby started with an experimental theatrical short by Art Clokey in 1955 called Gumbasia, which featured animated clay moving to jazz music. The film was seen by 20th Century Fox producer Sam Engel, who hired Clokey to develop a wholesome clay-animation series for television. Gumby, his faithful horse Pokey, and a whole cast of characters became household names once they had their own series, which continued a successful worldwide run well into the 1960s. This was the first time that clay, as a medium for stop-motion, had finally been used to full effect to create a mainstream pop icon. The creators’ studio, founded as Clokey Productions, was also commissioned by the Lutheran Church in 1959 to produce a show that could teach religious values to children, and the result was the Davey and Goliath series about a boy and his dog. This show used molded puppets dressed in real clothing, in a style more similar to European puppets, except that their stories involved much more dialogue. Their dialogue was achieved with paper stick-on mouths that would be replaced for each frame—one of the methods used in limited animation for TV, and which is still used in a digital fashion today (even for South Park!)

Gumby and Davey and Goliath had both faded into syndication and cult status by the 1970s and early ’80s, but each had their own rebirth as well. The New Adventures of Gumby brought the clay icon back in 1987, and was the first job for many animators who would later work on Nightmare Before Christmas, including Anthony Scott, who also got involved with Davey and Goliath’s comeback in 2004 (see Chapter 8, “An Interview with Anthony Scott”).

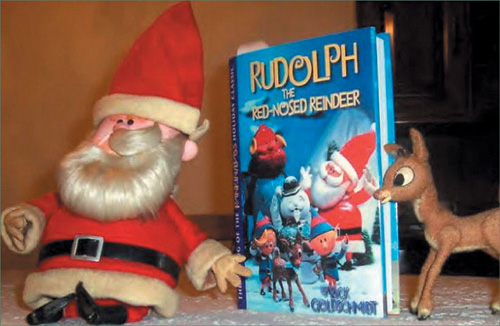

During the early days of Clokey Productions, another American studio that successfully brought stop-motion to television was Rankin-Bass, founded by Arthur Rankin Jr. and Jules Bass (see Figure 1.26). The studio started as an advertising company that was introduced to animation through a partnership with a Japanese animation studio. This deal led to the 1960 series New Adventures of Pinocchio, produced in their syndicated term for the stop-motion medium “Animagic.” The modest success of their first series gave them the resources to put 100 animators to work for 18 months creating their first television special, Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, which first aired on NBC in 1964. Rudolph (see Figure 1.27) became the longest-running special in the history of stop-motion, repeating every Christmas and becoming a wonderful holiday tradition.

Figure 1.26. Arthur Rankin Jr. and Jules Bass. (Courtesy of Rick Goldschmidt Archives/www.rankinbass.com.)

Figure 1.27. Rudolph and Santa as they appear today. (Courtesy of Rick Goldschmidt Archives/www.rankinbass.com.)

More Animagic specials followed throughout the ’60s and ’70s, often with holiday themes, such as Santa Claus Is Coming to Town, Here Comes Peter Cottontail, and Rudolph’s Shiny New Year. Since then, Rankin-Bass has segued more into 2D production, but their stop-motion series are still popular today and have been very influential to the medium. The fact that the animation was done in Japan makes their productions a unique cross-cultural phenomenon. While the stories and designs originated in America, the style of the animation is very much Japanese, in that the characters’ movements are expressed through a pantomime-like style with limited lip sync. The characters’ lip movements are not always fluid and exact, which could be because of language barriers in translating the dialogue. The most important thing to the animators was not the mouth positions, but more that you knew which character was speaking, which is a stylistic choice that is also common in 2D Anime films.

Elsewhere in the world, stop-motion had found its way onto television with series such as the German cold-war propaganda children’s show Sandmannchen (Little Sandman), the French/Polish series Coragol (about a globe-trotting bear, known as Jeremy in Canada), and Aardman’s Morph. The French series The Magic Roundabout, by Serge Danot, became even more popular in the UK and has more recently been resurrected through the CG feature film Dougal (2006). The design of Magic Roundabout was influenced by animator Ivor Wood, who went on to produce shows like Paddington Bear and Postman Pat for the BBC. The Nickelodeon network, which began in the U.S. in 1979, slowly began introducing some of these foreign stop-motion works to North America, partly through shows like Pinwheel. The 1980s introduced a wide variety of stop-motion to television, on shows such as Pee-Wee’s Playhouse, a Saturday morning show starring comedian Pee-Wee Herman. Each episode featured clay animation sequences with a girl named Penny, a family of dinosaurs, and occasionally a brief segment from George Pal’s Puppetoons. Several noted animators such as Peter Lord, Craig Bartlett, Steve Oakes, and David Daniels contributed their talents to the show. Another popular venue for stop-motion during this period was music videos, most notably in Peter Gabriel’s Sledgehammer and Big Time (1986). The animation in Sledgehammer was created by Aardman Studios, and the Brothers Quay made their contributions as well.

Will Vinton Studios became very famous for commercials and television work in addition to their short films. Vinton created his most famous Claymation characters, the California Raisins (see Figure 1.28), for an advertising campaign that spawned a series of entertaining TV specials, including the Emmy-winning Christmas special A Claymation Christmas Celebration. Years later, in the late 1990s, he produced the first prime-time stop-motion series, The PJs, featuring Eddie Murphy as the voice of the lead character Thurgood Stubbs. The PJs was created with another trademarked technique called Foamation, in which the puppets were made of foam latex and rubber so that they could be easily duplicated for use on different sets at the same time—something that would be much more difficult with clay on a short production schedule. Another short-lived stop-motion series, Gary & Mike, was created by Vinton Studios before the company was taken over by Phil Knight in 2002, and Will Vinton was laid off from the studio he had founded. Vinton has now started a new studio in Portland, called Freewill Entertainment, and is continuing to create new shows in stop-motion and CGI.

Stop-motion has appeared on television in other various forms well into the ’90s and the new millennium. San Francisco studio Danger Productions made a Saturday morning series Bump in the Night in 1994, about a monster named Mr. Bumpy and his various adventures. MTV started their own animation studio in New York and created a popular show called Celebrity Deathmatch, where puppet caricatures of celebrities would duke it out in a stadium wrestling ring. Independent animator Corky Quackenbush made a series of animated segments for the MAD TV comedy show, where classic stop-motion characters like Rudolph and Gumby were parodied in various violent situations. Many of these recent stop-motion sequences for television were not meant to be remembered for intricate flowing animation, but more for adult entertainment value and satire with a more crude style.

Today, stop-motion on television is very popular for children’s series such as Bob the Builder, The Koala Brothers, and Jojo’s Circus. On the other end of the age scale, adult audiences enjoy shows like Robot Chicken and The Wrong Coast. The stop-motion medium has had a rich history on the small screen and should continue to do so as long as there are good ideas for various audiences. To this day, there still has not been a CG television series that has rivaled the cultural impact of 2D shows like The Simpsons or stop-motion shows like Gumby, so in this arena, both mediums are still dominant.

When Walt Disney set out to make his first animated feature, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, the production was cursed with the name of “Disney’s folly” by much of Hollywood, because nobody believed that audiences could sit through a cartoon that long. The phenomenal success of that picture proved everyone wrong, of course. It took much longer for stop-motion animation to reach the same pinnacle of success in a feature-length format. In America, it was more common for the technique to be used for brief sequences or special effects inside live-action features, such as the Harryhausen pictures and more offbeat stuff like animator Bruce Bickford’s trippy clay animation sequences from Frank Zappa’s concert film Baby Snakes (1979). Stop-motion amazed audiences when used for short sequences like this, but the crudeness of early attempts made it an even riskier venture to hold an audience’s attention by itself for 75 to 90 minutes of screen time. Also, due to the time-consuming nature of stop-motion, making a feature-length motion picture with the technique has been a historical rarity compared to the number of shorter pieces in the past century.

What is believed to be the world’s first feature-length animated film is German animator Lotte Reiniger’s The Adventures of Prince Achmed from 1926 (see Figure 1.29). The film was created with cut-out figures entirely in silhouette, acting as a frame-by-frame extension of traditional shadow puppet theater, and it took three years to make.

Soon afterward, Ladislas Starewich created the first feature-length puppet film, The Tale of the Fox, which was finally released in France in 1941. Years later, Jiri Trnka made several stop-motion feature films, including The Emperor’s Nightingale and A Midsummer’s Nights Dream, which had limited releases in the United States as well as in Europe.

A stop-motion/live-action version of Alice in Wonderland was produced by animator Lou Bunin in 1948, but Disney’s version overshadowed it, and the film slipped into cult status over the years. The first American stop-motion feature was Hansel and Gretel: An Opera Fantasy, directed by John Paul and Michael Myerburg in 1954. The film’s score, based on an 1892 opera, was nominated for a Grammy and saw a few theatrical rereleases for years afterward. In addition to their popular TV specials, Rankin-Bass made some features in their Animagic stop-motion technique, starting with Willy McBean and His Magic Machine in 1965, followed by Mad Monster Party in 1967, and Rudolph and Frosty’s Christmas in July 1979. Clay animation found its way to limited screen releases in the 1980s with Pogo for President (1980, based on Walt Kelly’s famous comic strip) and Will Vinton’s Adventures of Mark Twain (1985). Vinton also used Claymation for the “Speed Demon” sequence in Michael Jackson’s feature film Moonwalker (1988).

In 1983, UK studio Cosgrove Hall made a foam puppet adaptation of Wind in the Willows, and George Lucas produced the film Twice Upon a Time, which was created in a technique called “Lumage.” This method employed flat textured cutouts that were lit from underneath to give a translucent quality. The result was a graphic 2D appearance, although the procedure was done with stop-motion cutout and replacement animation. Like most of these former stop-motion features, Twice Upon a Time was not marketed well enough to generate much of an audience. Many of these films found enough circulation in the early days of cable TV to gain cult followings among animation fans. Today, most of them remain lost treasures awaiting possible resurrection on DVD.

The biggest turning point for the sporadic, dismal performance of stop-motion features began in the early ’80s, when Disney animators Tim Burton and Henry Selick struck up a friendship while working together on The Fox and the Hound. In 1982, Burton was given the opportunity to direct a stop-motion short called Vincent, and while wrapping up the film, created some sketches for a poem entitled The Nightmare Before Christmas. Meanwhile, Selick left for San Francisco to focus on stop-motion commercials and short films of his own. Tim Burton left Disney and quickly became a successful feature film director, starting with Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure and Beetlejuice, both of which had some brilliant stop-motion effects weaved in (such as the classic Pee-Wee “Large Marge” scene!). As the ’80s segued into the ’90s, the industry saw the beginning of a renaissance for the animated feature film, partially inspired by Jeffrey Katzenberg’s involvement at Disney and brought on by the amazing success of Who Framed Roger Rabbit, The Little Mermaid, and Beauty and the Beast. The time was right for Burton and Selick to join forces and approach Disney, who still owned the rights to Burton’s poem and concept designs for The Nightmare Before Christmas (see Figure 1.30). Production began in 1990 for turning Burton’s vision into a big-budget feature film in stop-motion, which would be the first of its kind to receive worldwide distribution. Brilliantly executed, the film was a success in its initial 1993 release and continues to get better with age. Nightmare is one of the most significant films in the history of stop-motion animation, for the fact that it came out at exactly the right time, when the validity of using the technique for creature effects was challenged. It also captured the surrealism and charm of classic puppet films by Starewich and Trnka, and it used George Pal’s replacement technique for some of the characters’ dialogue. The film combined elements of these films with nostalgic nods to the Rankin-Bass holiday specials and brought them to a higher level of technical smoothness and artistry, all the while creating something fresh and new.

Figure 1.30. Jack Skellington and Sally from Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas. (Touchstone/Burton/Di Novi/The Kobal Collection.)

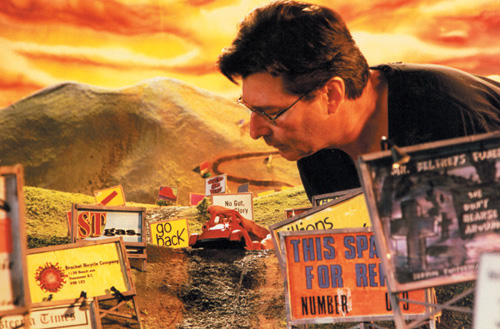

The success of Nightmare led director Henry Selick to create a follow-up feature, James and the Giant Peach, in 1996, which also featured live-action, CG, and cutout animation. Having now made two films aimed at children yet universal in their appeal, Selick’s next project was meant to be darker and more adult-oriented. He began production on a feature film based on the graphic novel Dark Town, which went through many changes until it was finally released under the title MonkeyBone in 2001. It was primarily a live-action film but featured a stop-motion monkey as a primary character along with many other surreal puppet effects. The film was not very successful at the box office, but the animation was inspired and blended well with the live actors.

More recently, Selick has created stop-motion effects for feature films like The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, and he has joined forces with Laika Entertainment to continue making films in CG and stop-motion.

1993 also brought another stop-motion feature from the UK, The Secret Adventures of Tom Thumb, directed by Dave Borthwick, which combined puppets with pixilated live actors to tell a dark tale similar in style to Svankmeyer and the Brothers Quay. The years since have also produced a Gumby feature film and a Russian production called The Miracle Maker, which tells the story of Jesus Christ using very realistic stop-motion puppets. Nick Park’s Oscar-winning Wallace & Gromit had also caught the world’s attention and led to a multipicture deal between DreamWorks and Aardman Animation Studios. DreamWorks, founded by Jeffrey Katzenberg, Steven Spielberg, and David Geffen, had ventured into animation with their 1998 releases of Antz and The Prince of Egypt, and wanted to continue supporting stop-motion animation. The first feature to result from this partnership was the release of Chicken Run in 2000, directed by Nick Park and Peter Lord. Described as “The Great Escape with chickens,” the film was one of the biggest hits of the year and took the medium of clay animation to new heights never before achieved on the big screen. The DreamWorks/Aardman team continued with pre-production on more features. The idea for a Wallace & Gromit feature had always been on their minds as part of the multipicture contract, so before long it became the next project to go into production. At the same time, Tim Burton started realizing a project based on a Russian folk tale called Corpse Bride, and production soon began on it as a stop-motion feature. Shortly before shooting began, the decision was made to shoot the film digitally, making it the first stop-motion feature in history to be shot without film. Both films became notorious for being top secret among industry insiders, and both were produced in the UK. Finally, after years of anticipation, Corpse Bride and Wallace & Gromit: Curse of the Were-Rabbit were released within weeks of each other in the Fall of 2005. Both were nominated for “Best Animated Feature” at the 2006 Oscars, and Wallace & Gromit took home the award yet again. Their simultaneous releases, nominations, and win were a historical first for the genre of the stop-motion animation feature. Both films featured outstanding animation that raised the bar to a whole new level of technical artistry. They were also groundbreaking in the way they combined classic stop-motion with the latest in digital compositing technology. What does this mainstream success mean for the medium of stop-motion animation today and in the future? Time will tell....

The history of this wonderful art form is vast and varied, and there are hundreds of other artists who have contributed to its exploration who I have regrettably not mentioned. There are also mysterious works that have been lost or forgotten, just waiting to be rediscovered and made new again. In that sense, the history of stop-motion is never antiquated but forever being discovered by those who dare to look back in hopes of finding inspiration for the future. I would encourage you to hunt for as many of these rare gems as you can, through the Internet or your local independent video store. Compared to other art forms, we’ve only scratched the surface of stop-motion animation, and there is still a long way to go.