David Bowes (pictured in Figure 3.1) is the founder, producer, director, and president of Bowes Productions, Inc., an award-winning stop-motion animation studio in Vancouver, BC, Canada. Since 1988, his company has produced a wide variety of animated productions, from television specials, commercials, and animated feature film elements, to production design, props, puppets, miniatures, and sets. Over the years, he has assembled a strong freelance team, Bowes & Associates, which continues to expand into new areas of stop-motion and CG productions. The company’s Web site is www.bowesproductions.com. I first met David by contacting him for advice on my stop-motion project Bad News back in 1999.

KEN: How did you get started with stop-motion animation?

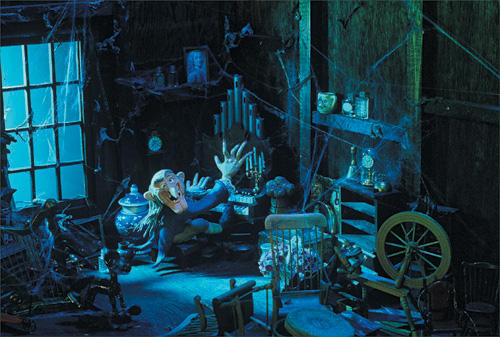

DAVID: It was actually the furthest thing from my mind when I decided in 1985 to attend Camosun College’s Visual Arts program in Victoria, BC. My intention was to learn gas-firing kilns and formulate glazes for sculpture. In the second year, we were required to take a basic animation course, where we had to incorporate six forms of animation—from line drawn, rear projection, pencil crayon, cut-out, cel, and (puppet) clay animation—into a one-minute piece. I created a short entitled At Half Past Midnight (see Figure 3.2) and incorporated the clay sequence at the end of the short with a clay character playing a pipe organ in a haunted house miniature attic. I wanted ghosts to fly out of the pipes while the character played, so I screwed the set to my living room floor, took a window frame with glass and screwed that down against the edge of the set, and then locked down a Super 8 camera another 4 feet from the window frame. I then took a long piece of wooden dowel with a felt pen taped to the end, and by looking through the viewfinder of the camera, I was able to mark the tops of the pipes of the model organ to register where the ghost would fly out. I then animated the ghost sequence separately on cels. When the time came to actually animate the clay character playing the organ, I simply replaced each cel on an animation peg bar every time I double framed the character movement. Two weeks later when the film came back to the college, I asked everybody to leave the room so I could project it alone (a practice which became a ritual). Lo and behold, it worked! The end result was magic. The ghosts were slightly out of focus, which added to the effect of them flying around the room while this crazy little psychotic character played Bach’s “Toccata and Fugue in D Minor.” I was totally mesmerized, as it was one of those perfect moments where I knew exactly what I wanted to do as a career.

KEN: So then how did this moment lead to starting your own studio?

DAVID: After I graduated from the 2-year program, I decided to take a 1-year independent study to further my animation skills and ended up creating four films using the college’s 16mm Bolex, which I taught myself how to use. The first time I used the camera, I left the exposure in the timed exposure (T) position, and my entire 2-minute animated short entitled Canadian Express was overexposed. With a lesson learned, I immediately successfully reshot. My fourth film, The Mad Potter, I screened at the University of Victoria as it had one of the few 16mm projectors in town that could play a magnetic sound stripe. While I was screening my film, Gresham Bradley from the Knowledge Network just happened to walk by and very excitedly asked me if he could air my piece. They paid for an original music score and editing, and while I was in the edit suite late one night in Vancouver, the editor commented that the short was pretty cool and stated, “You should start a business.” This comment influenced me, and before I knew it I was sitting with a corporate lawyer. In the end, as his fee was beyond my budget, I purchased a book, How to Incorporate Your Own Business. I registered the company using my last name for two reasons. First, in college it was a standard, and second, and most importantly, I felt it would give me the drive to stay focused and succeed. Next, I purchased my own 16mm Bolex camera. I remember waking up the next morning and saying to myself, “Well, you’re a company with a Bolex camera. Now what?” That morning I started making phone calls, and over the next several weeks found that most companies and agencies wanted to see a commercial demo tape, which I didn’t have. At that time, the Carmanah Valley Rainforest, located on the west coast of Vancouver Island, was big in the media, so I decided to make a commercial about it called The Talking Rainforest (see Figure 3.3). I approached the National Film Board of Canada for assistance, and they recommended that I contact the magazine publisher of Adbusters in Vancouver, who helped me produce a 30-second spot making people aware of our vanishing rainforests. When it finally aired 8 months after conception on BCTV, now Global TV, it was tough to watch it go by so quickly after spending so much time and money on it. In the end, however, it was extremely positive for the Carmanah Valley, and it became the flagship of my company.

With the Mad Potter now on the air with the Knowledge Network, and the media hype with The Talking Rainforest, a production company, May Street Productions, based in Victoria, took notice. They wanted a clay character called “Morf” to interact with live action throughout their children’s series entitled Take Off. Basically this was our first paying contract. During this production, my then business partner and I attended the Banff Television Festival and walked away with a contract with Calico Pix/CBC for the one-hour special entitled Alligator Pie. We produced two clay animated segments. Clay was very popular in the late ’80s and early ’90s, with credit to Will Vinton’s California Raisins series of commercials. As a result, our work became fairly steady. We secured a contract with Fuji Television of Japan, producing clay segments for its ongoing children’s series Hirake Ponkiki, teaching children English. Various service contracts continued coming in from station IDs, including elements for commercials, magazines, and a few 2D animated contracts. In 1996, we made the decision to move from Victoria to Vancouver with the award of a new commercial for General Mills. This was a very effective business decision, as it made it easier to meet with clients and secure additional contracts. The next big turning point was our first half-hour Halloween special for YTV of Canada entitled Twisteeria (see Figure 3.4), which won the 1999 Leo Award for Best Animated Program and was nominated for four Gemini Awards. Since then, we have focused on commercials, creating elements for series and features mostly, and more recently we have started transitioning into computer animation with our latest television series. I feel we’ve picked a good time for this transition, based on the fact that there are various software programs out now that can replicate the look of stop-motion. I don’t think it will ever be the same, but it’s pretty scary when you look at how close it is. We don’t intend to break away from stop-motion completely, but rather develop projects that combine the two.

KEN: Do you have a particular favorite project from the past 17 years?

DAVID: Yes, the animation sequence we did for Paramount Pictures’ Nickelodeon on the feature film Snow Day was not only a favorite of mine, but also a favorite of the team who worked on it. The phone call came in, they flew us to Calgary for a production meeting, we returned to assemble our gear, and then flew back to Calgary for the shoot. It ended up being one of our favorites based on the fact that the overall production went off without a hitch and in the end we were treated the way you should be treated in the industry. Another highlight was a Christmas commercial we did for the ad agency Linguis for their client Western Wireless Communications—Cellular One in the United States (see Figure 3.5). You always have to expect hiccups during jobs in production, but this was another memorable one that was on time and on budget, and the client loved it. In the end, however, one of my personal visual favorites was the clay sequence we produced for Alligator Pie with Dennis Lee’s poem The sitter and the butter and the better batter fritter.

KEN: Can you explain a bit about the bidding process and how projects get approved for production?

DAVID: For service work, it usually starts with a phone call or e-mail from a production company or ad agency requesting a demo. Also, we receive inquires on our Web site, from an advertisement in a trade magazine or, most often, by word of mouth. Your demo is reviewed based on the quality of past productions, or anything on the reel that might relate to what the client or director is looking for. If they like what they see, you’re placed into their “A” list, which then follows through with a conference call with the producer and director. You need to understand their script and/or storyboard and be extremely creative and original with your approach. One has to be well prepared prior to this call and have reviewed all aspects with the heads of your company’s department, from character or set designers, puppet or set supervisors, key animation supervisor, post supervisor, etc.

It boils down to whoever does [his] homework and presents the best presentation to the client will get the job. Of course, one of the most important aspects of the bid is the budget. Generally, whoever is approaching you with a project already has a budget in mind, so I generally ask [him] what that figure is and then work backward and detail what we can do for that price. The bidding can be very straightforward at times, and other times there’s a lot of number crunching with much patience involved. Sometimes the budget may not be as high as we would like to see it, but we consider the gig anyways, based on the fact that we like the creative and it would be a nice addition to our reel. There’s actually a lot of work involved in preparing your bid, with no guarantees. There may be six other companies bidding on the same job, and they are all very capable, so as a team you have to come up with an approach that has an edge. It can be pretty nerve-racking waiting for the phone call to see who has been awarded the contract, but in the end, I love the hunt for the job. If you do not get the job, you need to move forward and not take it to heart. If, on the other hand, the job is awarded to you, you really need to hit the ground running. There might be only 6 to 12 weeks to produce a spot, and you need to have a full production team working within days. The complete stop-motion animation and effects we produced for MTV and Insight Films’ Monster Island went into production September 5 to December 23, which was an intense effort for our team. Keep in mind there were 4 months of bidding and number crunching for the contract prior to starting.

There is a different approach altogether with your own in-house production concepts, such as shorts, specials, and series being approved for development. It all starts with a well-thought-out idea, which can take weeks, months, or even longer to get to concept. Again, I can’t stress how important it is that your idea be as strong as possible. Ask yourself if your story concept can sustain 26 to 52 episodes and avoid adding holiday themes as springboards such as Christmas, Halloween, etc. Once you feel confident with your proposal, you need to get a Canadian broadcaster on board in order to trigger funding within Canada. This stage boils down to the “pitch.” I always keep in mind that the pitch should be no longer than 1 minute or one paragraph. If it takes 5 minutes to get your idea across, consider going back to the drawing board. Remember, you may only have one shot at it.

Here’s an eye opener: Up to a thousand proposals a year on average are submitted to a children’s broadcaster, so your idea must stand out. If your idea is good and it’s what they’re looking for, you’ll know right away. If you’ve peeked their interest, then the second phase takes place, which means you’ll then elaborate with more detail on the concept and possibly some visual creative. Keep in mind that a visual presentation may work against you. I’ve pitched with full character and set designs and sadly found that it was not what a particular broadcaster liked. It’s important to know your broadcaster well. Teletoon, for example, may have a different format from YTV of Canada, Cartoon Network, or Nickelodeon, in terms of what kinds of shows they are airing. Therefore, you need to watch what is on TV, what kids are watching, what’s new and exciting.

It’s ironic because adults make cartoons and children watch them, excluding primetime animation, so you have to know your audience. You may think you have a great show, but if two kids sitting on the couch watching it decide they don’t like it, multiply that a thousand times over, and the ratings won’t be there. The bottom line is to create or find a good idea, know your broadcaster and age demographics, and be passionate about your idea.

On a final note, getting picked up by a broadcaster to develop your concept is a major accomplishment. After this, your next hurdle is raising the capital. It takes a dedicated group of experienced and knowledgeable executive producers to secure the financing, which may take years. One could write an entire book on this subject alone.

KEN: What else is important to know for someone running his own studio?

DAVID: Starting your own studio is not as simple as one might dream. You have to be a risk taker. It takes a lot of time, money, investment, and responsibility. Capital is always the most important aspect of any business. One must be prepared to commit to long hours, perseverance, and be prepared for a lot of sacrifices. It’s very rare that one becomes a success overnight. Having said this, if you choose to consider your own studio, focus on building a reel first; if you don’t have a product people want, you won’t have any revenue. Build a reel and learn to promote yourself; what better person than yourself? A publicist will eventually come into the picture once you’re established. The Internet is a relatively fast and cheap way to promote your work and especially feature some of your animated shorts; however, keep in mind: You can’t promote what you don’t have. It may take years to obtain a great visual resume; however, sometimes in this ecliptic market, it’s not all about the polished look. Lesser quality of puppets and even movement in some cases can be well received with a good idea and good storytelling. In the end, however, it may be more rewarding and your best option to work for a studio that is already established and gain experience through the creative, leaving the business headaches to the CEO. The film industry can be a tough business at times, and it’s true what they say: “You’re only as good as your last gig.” If you’re not prepared for the down times, well, the rest is left unsaid.

KEN: Which materials have you found work best for building puppets in a stop-motion production?

DAVID: Partly it depends on your budget. We always say, your animation is only as good as your armature. In the past, we’ve worked with lead armatures with brass fittings, but moved away from them due to the toxic component of the lead. We all like to use ball-and-sockets, but if our budget is limited, then aluminum wire is usually the way to go, and you can obtain some very nice movements. This again is governed by the skill and experience of the animator. You really need a ball and socket armature if the puppet(s) requires endurance with many scenes, you’re looking for precise movements, or the puppet is large with weight, but even ball and sockets can break. For Monster Island, our team of extremely experienced puppet fabricators created one praying mantis and several ants out of polyurethane and foam covering ball-and-socket armatures (see Figure 3.6). This was the only way to go based on the weight. Designing the puppets out of clay would have been impossible. For us, foam rubber latex is such a joy to work with because for years while using clay the characters would need constant cleanup after every shot, and during the shoot the animator had to spend more time cleaning between frames. Moving to foam allowed the animators to focus on their animation instead of worrying about cleanup. As a bonus, the foam puppets can last for years, as long as you keep them in a controlled environment.

Figure 3.6. Insight Films/MTV’s Monster Island praying mantis. (Copyright 2003 Bowes Productions Inc.)

I still like clay, as it has a certain look to it, and the process is rather therapeutic, working with this organic material in front of you. In the mid to late ’90s, clay appeared to be less common in North America compared to England, and many were concerned with the rise of CGI that clay was going to disappear altogether. But certain companies stayed true to the medium and were able to place clay into the “here to stay” category. The most obvious being Aardman Studios in Bristol with the huge success of Wallace and Gromit, and the list goes on.

Now there are many children’s series being shot in clay throughout the international markets. If you look at the preschool lineup for the BBC, it’s either clay or stop-motion. Over the years, there has been this rival battle between CGI and stop-motion, but no matter what medium is used, it all boils down to a good idea and good storytelling. In my opinion, all the various forms of animation have found their place. Every once in a while, you’ll hear someone say 2D classical is a dying art. I simply point out The Simpson’s, Family Guy, etc.

KEN: Do you think there are any untapped markets or trends that stop-motion is starting to cross into?

DAVID: Well, that’s a tough question. It’s like asking where you think the next real-estate boom will be. Just when you think everything possible has been done in animation, someone comes along with an alternate approach. I don’t think anything is truly new, only revisited by utilizing the ever-changing computer technology. In order to be more effective with limited budgets, some stop-motion companies have turned to streamlining the lip sync with their puppets by compositing CGI mouths, which have proven to be quite effective. Those same studios have successfully composited clay heads and faces on live-action bodies or vice versa. In the end, it’s creative people who recognize the computer as a tool and effectively explore the combination of stop-motion and CGI that will find new trends.

Other studios are focusing on the ideas and not worrying so much with the quality of movement or puppets, which in (some) cases, works. Some label it as “guerilla animation” or “the collage look.” Again, with the right idea, the wacky stuff is funny to watch, if you don’t really concern yourself with the quality. My feeling is that Beavis & Butthead paved the way to the acceptance of crude animation with the viewer. On one side of the fence, you had the creators who threw caution to the wind without a concern for exquisite animation, and on the other side of the fence, you had the purists who cringed at it. But in the end, it was the viewer who ultimately accepted this and started this trend.

KEN: What advice do you have for aspiring stop-motion animators?

DAVID: First off, in any form of animation, it can take years of practice, patience, dedication, and experience on many productions to perfect your skill to become a professional. Some individuals can become a “star” (as we say in the industry) overnight, but this still requires hundreds and hundreds of committed hours in front of the camera. But, like everyone who eventually became a professional, they had to start somewhere.

Taking into account that you have the necessary equipment for filming, find out if you really have a passion for it by animating some simple objects found around the house, or a plastic action doll or something with simple armature. Don’t worry too much about trying to make a perfect sculptured puppet; this will come down the road and, again, to reach a professional level of a puppet fabricator can take years. Learn your skill and gain experience. I recommend in the beginning to concentrate on short little lessons by using a small clay ball. Teach yourself about constants, tempo, timing, movement, weight, and holds. An excellent series for learning animation was produced by the renowned animator Norman McLaren for the National Film Board of Canada, entitled “Animated Motion” (NFB 1976-8). This series visually explains the basics and more advanced techniques of traditional animation, but most importantly, can be translated to stop-motion. This series can still be ordered through the NFB and is a great addition to your library.

Watch and study as many stop-motion animated productions as possible, and if you can freeze frame and then advance frame by frame, all the better. Study movement by watching people, animals, and moving objects around you. Act out movements based on 24 frames a second in front of a mirror, and time yourself with a stopwatch. In the end, animation is replicating the reality of movement with everyday life and transferring it into a character, car, tree, dog, etc.

Learn your skill and gain confidence before you set out to create an elaborate short or tell a story to avoid frustration. Having said this, it all depends on the individual; many skills are learned by working through the challenges presented while working on your short. This, of course, was the direction I took.

If you truly have passion for becoming an animator, you should consider enrolling in a classical animation course to further your training. This will help immensely with all forms of animation and may even help you land a job. Most studios, especially CGI studios, are now leaning toward hiring individuals with this form of training over those without it. There are many graduates out there, and everyone is searching for the one job.

Once you have become a good animator, you need to be persistent and continue to better yourself with every gig. You should realize that a career in animation, especially stop-motion, might require you to become a freelancer, and you must be willing to travel where the productions are. One moment you might be in Vancouver, then Toronto...next you might be in England.

In the end, learn your trade extremely well to ensure this rewarding career will continue to give you the satisfaction creatively and financially. Most important, the passion from each individual learning stop-motion will keep this age-old form of animation alive and continue to hold its place within the world of animation.