Cybercrime

Abstract

This chapter introduces the reader to various types of crime that’s committed online, and might pose a threat to them. It discusses what cybercrime is, how criminals choose targets, identity theft, common scams, social engineering, and hacking. In addition to teaching the reader how to identify common threats, we also discuss tools that may be used to protect them.

Keywords

Cyber safety; cybercrime; identity theft; scams; social engineering; hacking

Sometimes when people use the Internet, they have a false sense of security. You’re sitting in your home, comfortable and enjoying the time you’re spending surfing the Web. You assume no one can physically harm you through a computer screen, so any sense of danger doesn’t even register in our minds. Some computers already have security programs installed, and keeping the default settings is probably good enough. After all, you have to trust the people who made those programs right? Besides, if anything happens, it will probably happen to someone else.

It’s easy to lull yourself into a false sense of safety. While you should feel comfortable using the Internet, you should also be wary. After all, anything that could happen to someone else could happen to you.

What Is a Cybercriminal?

A cybercriminal is a person who conducts some form of illegal activity using computers or other digital technology such as the Internet. The criminal may use computer expertise, knowledge of human behavior, and a variety of tools and services to achieve his or her goal. The kinds of crimes a cybercriminal may be involved in can include hacking, identity theft, online scams and fraud, creating and disseminating malware, or attacks on computer systems and sites. The core factor of what makes a crime a cybercrime is that it’s directed at a computer or other devices and/or these technologies are used to commit the crime.

Cybercrime is prevalent because the Internet has become a major part of people’s lives. In 2014, the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) reported they received 269,422 complaints from people with an adjusted dollar loss of $800,492,0731 (Internet Crime Complaint Center, 2014). These numbers of course only reflect reported crimes, and not the numerous others who fall victim but never report it because they’re too embarrassed or for other reasons.

How Criminals Choose Their Targets

The way that cybercriminals choose a target depends on their motivation. As we’ll see later in this chapter, hackers will attack systems for a wide variety of reasons, ranging from altruistic intentions, personal glory, revenge, espionage, and/or financial gain. As we’ll see in this chapter, the major reasons online crimes are committed are for money, sex, or power.

Cybercriminals often don’t choose a particular person. The victim may be selected because they responded to an ad or email, or came in contact with the criminal through some other means. Perhaps you chatted with the wrong person, visited a site and inadvertently downloaded malware, or crossed the path of the criminal in some other way. In this scenario they didn’t choose you personally, and didn’t care if it was you or someone else who’d be the victim.

Criminals are drawn to where their targets are. If a pedophile wants to meet a child, it makes sense that he or she would be drawn to a site that caters to children. Similarly, if you wanted to get people’s credit card numbers, you might hack a site where people enter that information. Just as you or your children are drawn to a site for a particular service or functionality, a cybercriminal will follow because it has the data or people they’re looking for.

In some cases, a target is selected for very specific reasons. If you had a past relationship with someone, they might upload inappropriate picture to a site. They may stalk you online, bully you, threaten or coerce you in some way. In the same way, a company may be directly targeted because they are an inviting target, or the cybercriminal had a particular ax to grind, such as being a disgruntled employee or seeking revenge for some reason. As you can see from this, a cybercriminal isn’t always the creepy nerd living in a creepy apartment that’s often depicted in TV and movies. They very well may be someone you know and would never expect.

Identity Theft

Identity theft is the act of stealing a living or deceased person’s identity, and using their information for the purposes of fraud. By impersonating another person, you can conceal your own identity, and use their credit history to acquire new sources of revenue, use services under their name, or use it for other personal gain. Once an identity thief has enough of your information, they can use it in a variety of ways:

![]() Credit card or bank/financial fraud.

Credit card or bank/financial fraud.

![]() Rent a house or apply for a mortgage.

Rent a house or apply for a mortgage.

![]() Obtain government documents (i.e., driver’s license, apply for government benefits).

Obtain government documents (i.e., driver’s license, apply for government benefits).

![]() Obtain a job using your national identification number (e.g., Social Security number). This might be done to bypass illegal immigration constraints, so they can work illegally.

Obtain a job using your national identification number (e.g., Social Security number). This might be done to bypass illegal immigration constraints, so they can work illegally.

![]() Get medical services, causing illnesses and injuries that you never had to be associated with in your medical record, and possibly accruing medical bills under your name. If insurance is used, it could also affect the available benefits remaining.

Get medical services, causing illnesses and injuries that you never had to be associated with in your medical record, and possibly accruing medical bills under your name. If insurance is used, it could also affect the available benefits remaining.

![]() Provide identification in your name during an arrest, leading to your name being associated with a crime, and possibly a warrant issued for your arrest.

Provide identification in your name during an arrest, leading to your name being associated with a crime, and possibly a warrant issued for your arrest.

The people who steal the identity of others can be any age or gender, as seen in the 2015 arrest of 72-year-old Cathryn Parker who was living under at least 74 different aliases and stole 7 people’s identities (Serna, 2015). Most of the people she targeted were production crew members working in Hollywood, and used other people’s information to lease a house, pay utilities, and acquire credit cards. She also had a previous mail fraud conviction in Hawaii for using a Jenny Craig Corp. travel account to buy plane tickets, which she then resold for $500 apiece.

Identity theft has been linked to organized crime, petty criminals who have the opportunity to use your information for personal gain, and could even been committed by a friend, family member, or someone else you know. In a survey conducted by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), it was found that 16% of victims had a personal relationship with the thief, with 6% of the thieves being family members or relatives, 8% being friends, neighbors or in-house employees, and 2% being a coworker (Federal Trade Commission, 2007). Being most people don’t know who stole their identity, these numbers probably underrepresent the number of people known to victims who have stolen their identity.

Controlling the Information You Provide

To steal someone’s identity, you need to acquire information that can be used to access a person’s accounts, obtain documents, and complete applications that can be made in that person’s name. The key details an identity thief will look for include:

![]() National identity numbers, such as a Social Security number or Social Insurance Number

National identity numbers, such as a Social Security number or Social Insurance Number

![]() Government document numbers, inclusive to your driver’s license and passport numbers

Government document numbers, inclusive to your driver’s license and passport numbers

![]() Physical Addresses, such as where you live

Physical Addresses, such as where you live

![]() Usernames, passwords, and personal identification numbers (PIN)

Usernames, passwords, and personal identification numbers (PIN)

![]() Financial account numbers, such as bank account numbers, and the numbers, expiry dates, and last three digits printed on the signature panel of your credit cards

Financial account numbers, such as bank account numbers, and the numbers, expiry dates, and last three digits printed on the signature panel of your credit cards

![]() Information that’s commonly used for security questions, such as your mother’s maiden name

Information that’s commonly used for security questions, such as your mother’s maiden name

The information an identity thief needs can be acquired in a variety of ways. A thief could look at social media accounts to find your full name, and links to the accounts of your friends and family, and posts wishing you a happy birthday will reveal your birthdate and often how old you are. Online resumes can provide information on past and present employers, and possibly your address and phone number. If you have a blog (especially one used as an online diary or journal), you may have published a goldmine of personal details. As we’ve seen in other chapters of this book, to block a potential thief from viewing these details, you want to manage what facets of your life are publicly accessible using privacy settings on an app or site, and avoid posting personally revealing or sensitive information online.

Once a person has enough details about you, they may use it to access your online accounts. For example, if your email address appears on a social media site, a thief could go to the email site and click a Forgot Password link, which might present a security question asking for your mother’s maiden name, your hometown, or the name of your pet, which has already been gathered from previous investigation. Once they gain access to the account, they can read emails from sites you have accounts with, see monthly statements emailed to you, view your contacts, and see other information that may be useful. If they choose to try and gain access to a financial account (such as one accessed through a credit card or banking site), they might transfer funds or use the account numbers to make unauthorized charges.

Protecting yourself online can seem daunting, but it isn’t hopeless. As we discussed in previous chapters, using strong passwords, nonstandard security questions and answers, and two-factor authentication whenever possible helps to prevent potential hackers from easily accessing your accounts. Limiting what information is available online, by being careful what you post, and not filling out any optional fields on accounts and forms will also limit what a hacker is able to see if he or she gains access.

You should also control what information people are able to acquire through physical means. If someone in your home or workplace can get a hold of your purse or wallet, they could quickly steal the information from there. If they’re not locked or secure, any national identity cards, passports, or other documents in your home could be stolen by someone working or visiting your home. Chances are you’d never notice they were gone until you needed them, giving a thief considerable time to use the information.

A key to controlling information is to look at it as an asset. While we’ve been rightly trained to look at financial account numbers as being worthy of protection, you should look at other details of your life as valuable. Having the right combination of details would enable them to apply for new cards, steal your identity, or forge a new one using your information.

Child Identity Theft

Children are a common target of identity theft. Unlike adults, they have clean credit reports, and because they have no reason to check monthly statements or credit rating, the theft of their identity can go unnoticed for years. It isn’t until later in life when they apply for student loans or a credit card, try and rent an apartment, or do any of the other things we take for granted in starting adult life that the problem is actually discovered. Reports have found that 10.7% of children have had their Social Security number used by someone else, and credit reports fail to detect 99% of child identity theft cases (May, 2012).

A child’s identity can easily be stolen by someone who acquires their national identity number, such as a Social Security number. Once they have this, the thief can use a new birthdate so the identity doesn’t appear as a minor, apply for other forms of identification, open new lines of credit, and qualify for government and medical benefits. When the child turns 18, his or her name and Social Security number is now associated a poor credit history and an older identity.

Using a credit monitoring service can help in identifying whether your child’s identity has been stolen. Experian (www.experian.com) has a service called Family Secure (www.familysecure.com), which (for a fee) will monitor your child’s personal information to determine if they have a credit file. With the information on file, if someone attempts to use their information to apply for credit, a lender is notified that the credit report requested is associated with a minor. Another free service, in which AllClearID has partnered with TransUnion (www.transunion.com) is called ChildScan (https://www.allclearid.com/personal/services/monitoring-services/), which scans databases for your child’s Social Security number. If an instance of fraud is found, you can then have it investigated and have the child’s stolen identity repaired.

An effective way to protect your child’s identity is to freeze their credit. In doing so, creditors won’t have access to their credit report, and will generally decline opening a new account. The catch 22 of this is that credit reporting agencies traditionally don’t have a report on a person until they or someone else applies for credit in their name. To remedy the problem, 19 states have enacted legislation that allows a parent or guardian to have a credit record created and frozen for a child. Equifax (www.equifax.com) allows you to put a freeze on your child’s records in all 50 states.

Social Engineering

One of the easiest ways to gather information about you involves trickery. Social engineering is the practice of using various techniques to get people to reveal sensitive or personal information. By understanding how people act and react, a person influences others into performing actions or revealing confidential details. Using manipulation, technological means, or documents you’ve made accessible, the person is able to gather facts about you or another target. If done right, you won’t realize you’ve given away information to the wrong person until it’s too late, if at all.

There are many techniques that can be used to coax or convince a person to willingly give up information. A common method is called pretexting, in which you create a scenario that will persuade a person to perform some action or reveal the information you want. To give you an idea of how this might work, consider these situations:

![]() You might receive a call at work from someone claiming to be in the IT department, who says there’s a problem with your network account. After some discussion, they ask for your username and password.

You might receive a call at work from someone claiming to be in the IT department, who says there’s a problem with your network account. After some discussion, they ask for your username and password.

![]() Someone claiming to be with the police, FBI, or other law enforcement call you, a family member, friend, or neighbor, and say that your name came up in an investigation. They wonder if it’s an identity confusion, and want some personal information to clear things up.

Someone claiming to be with the police, FBI, or other law enforcement call you, a family member, friend, or neighbor, and say that your name came up in an investigation. They wonder if it’s an identity confusion, and want some personal information to clear things up.

![]() Someone saying they’re from the bank, a credit card company, or Internal Revenue Service (IRS) calls you and asks you to confirm some information to prove they’re talking to the right person. They ask for bank account numbers, Social Security number, access codes, or other financial details.

Someone saying they’re from the bank, a credit card company, or Internal Revenue Service (IRS) calls you and asks you to confirm some information to prove they’re talking to the right person. They ask for bank account numbers, Social Security number, access codes, or other financial details.

The reason people are easily manipulated into giving away information is because they’re convinced it’s in their best interest to do so, or because they believe they’re helping in some way. If the person claims to be in some position of authority, the target believes they have the right to know this information. After all, we’re trained to answer and work with authority figures, and not question them.

Another way social engineering is used to gather sensitive details is through the use of surveys. Perhaps there’s an enticement of some reward, the person conducting the survey is personable, or you want to help the person out by answering a few questions. Regardless of the reason, the results can often be surprising.

When InfoSecurity Europe (www.infosecurityeurope.com) conducted their second annual survey, they asked office workers at Waterloo Station in London, England, a series of questions with the reward of receiving a cheap pen. The questions included asking people to reveal their password, which 90% of those questions did. Of those questioned, 75% disclosed their password when asked “What is your password?” and 15% gave their password after some additional questions, such as asking the category their password fell into. Applying some social engineering tricks, a CEO of a company initially refused to compromise security and give up his password, but later said it was his daughter’s name. When asked what his daughter’s name was, he replied without thinking, thereby giving up his password.

While most people in this survey gave their password when asked, a social engineer will often structure the questions so it doesn’t seem like you’re revealing anything important. You may be in a chat room or conversation, and asked seemingly innocuous questions or drawn into a conversation where you reveal more as your trust in the person builds. The information can also be drawn out of you in ways you wouldn’t consider. For example, you may have seen questions posted on Facebook notes or in email, where you’re asked to share things that wouldn’t normally come up in conversation so others can learn more about you. They may seem funny or silly, but if you searched Google for “Facebook notes questions,” some of the types of questions include:

While these may not seem important, especially when mixed in with fifty or a hundred other questions, you’ll notice that these are also common security questions used if you need to reset a password. Even if a social engineer didn’t send you the questions, they may be able to read ones you’ve answered previously by looking at your previous posts or Notes section.

Protecting yourself from social engineering requires being aware of the potential security risks, and taking steps to minimize them. In addition to the various tips we’ve discussed in relation to specific kinds of interactions (e.g., chat rooms and email) here are some additional tips:

![]() Be mindful of the information you post on the Internet, and realize it could be visible to strangers. If you’re talking with someone you don’t know in real life (i.e., Facebook friends, people in chat, those who call you), be wary of them. After all, they’re still a stranger, even though they may have built up some trust.

Be mindful of the information you post on the Internet, and realize it could be visible to strangers. If you’re talking with someone you don’t know in real life (i.e., Facebook friends, people in chat, those who call you), be wary of them. After all, they’re still a stranger, even though they may have built up some trust.

![]() Question (and ask yourself) why someone is asking for the information. If you don’t feel comfortable answering, then don’t.

Question (and ask yourself) why someone is asking for the information. If you don’t feel comfortable answering, then don’t.

![]() Never reveal personal, financial, or other sensitive information over the phone or Internet. If it’s in person, make sure it’s in a secure location, such as the offices of your bank.

Never reveal personal, financial, or other sensitive information over the phone or Internet. If it’s in person, make sure it’s in a secure location, such as the offices of your bank.

![]() Realize that anyone in an IT department won’t request information like usernames and passwords over the phone or in an email.

Realize that anyone in an IT department won’t request information like usernames and passwords over the phone or in an email.

![]() If a caller asks for confidential information, ask for their contact information, and then verify that it’s real. Don’t trust the phone number they give you, as it may be false. Use the phone book, dial information, or use the company’s website (if you’re familiar with it) to get the correct phone number, and have them redirect you to that person’s extension. If they claim to be from a financial institution, you could call the number on your monthly statement.

If a caller asks for confidential information, ask for their contact information, and then verify that it’s real. Don’t trust the phone number they give you, as it may be false. Use the phone book, dial information, or use the company’s website (if you’re familiar with it) to get the correct phone number, and have them redirect you to that person’s extension. If they claim to be from a financial institution, you could call the number on your monthly statement.

Technology and Social Engineering

Different communication methods are used by social engineers to find and target a victim, including the mail, phone, email, instant messaging, and other Web-based technologies. Since the early days of the Internet, various ploys have been used to get credit card numbers and other personal details. Some would use it to setup fake accounts with Internet Service Providers, so that they could exchange pirated software, while others used the information to access other people’s accounts, commit fraud, or other crimes. As the years progressed, using the Web has become a mainstay for cybercriminals to find and interact with potential targets.

Phishing is a common process in which cybercriminals try and fool you into revealing login credentials, financial details, and/or other sensitive information that can be later used to commit fraud or access accounts. The attacker will send messages that appear to come from an official source, such as a bank, credit card company, auction site, social media site, or another popular site that can be used to lure victims. Because it appears to come from a trusted source, and may include the logo of the company it’s posing as, you’re more likely to believe it’s legitimate. If the site contains a link, clicking it may download malware or take you to a bogus website where you’ll be asked to enter personal, financial, and other sensitive information.

The term phish is a homonym for “fish,” as in you have to cast a big net to catch a few fish, which also describes how it works. A scammer will send out unsolicited email (SPAM), text messages, or other forms of communication in bulk. While many people will dismiss the message, a few will respond to it. There are some variations phishing, including:

![]() Spear phishing, where an individual or group of people in the same company or department are the focus of an attack. Because it addresses a specific person or group, it may have information related to them, and even appear to be coming from another area of the organization (such as Accounting or the IT department); there is a great likelihood for recipients to open and respond to it.

Spear phishing, where an individual or group of people in the same company or department are the focus of an attack. Because it addresses a specific person or group, it may have information related to them, and even appear to be coming from another area of the organization (such as Accounting or the IT department); there is a great likelihood for recipients to open and respond to it.

![]() Clone phishing, where a previously sent email that’s legitimate is copied and resent, with alterations made (such as a link to a bogus site and a malware attachment). Because the original email is known to be real, and the cloned one has the same content but perhaps claims to be an updated or resent version of the original, people will believe it to be real and likely to open it.

Clone phishing, where a previously sent email that’s legitimate is copied and resent, with alterations made (such as a link to a bogus site and a malware attachment). Because the original email is known to be real, and the cloned one has the same content but perhaps claims to be an updated or resent version of the original, people will believe it to be real and likely to open it.

![]() Whaling, where management and senior executives are targeted in an attack. An email may appear to be customer complaint, legal document, subpoena, or other messages that are likely to be opened by the recipient.

Whaling, where management and senior executives are targeted in an attack. An email may appear to be customer complaint, legal document, subpoena, or other messages that are likely to be opened by the recipient.

Many of the things mentioned above are sent in emails with either links to other sites or attachments that they want you to open. The sites that may be included in links within the message can be quite elaborate in mimicking a legitimate site. A copycat site may have a similar URL to the real company’s site, and the person running it may have even used website tools to promote the site in search engine results, so it appears to be the real company when you do a search. Even government sites have been copied, asking fees for services that are free to citizens, and requesting payment for licenses, passports, and other items at an excessive price. Another indication that it’s a copycat site may be that they request you provide information on an insecure site (i.e., not using HTTPS).

Even though the copycat site appears the same at face value, you should try and pay attention to any errors or odd things about the site. If you’re visiting a site that’s familiar to you, it may be obvious that there have been changes. Perhaps the logo is outdated, the URL is different, or the quality of the site doesn’t seem to match the company’s professional image. Even if it’s your first visit, you may notice spelling and grammar mistakes, even to the point that it seems created by someone who speaks English as a second language or used Google Translate to generate the text. If it seems wrong, don’t trust the site.

Suspicious Emails and SPAM

As we mentioned, SPAM is a term used to describe unsolicited email or messages that are sent to groups of people. The person sending the message is referred to as a spammer. The email may contain advertising, and simply be an annoying marketing tactic, or could be used by scammers and hackers to find potential victims.

A spammer may also post on various sites, or implement software known as a spambot. The spambot may be designed to gather email addresses from sources on the Internet so that email can be sent to those people, or create new accounts to send email or post messages on a site. A spambot could also be used to search the Internet for comment sections, guestbooks, wikis, or other forums so it can post a message. You may have seen these and thought it was an actual person claiming they made huge amounts of money working from home, or providing a link to a video sharing, dating, or pornography site.

SPAM is used for a variety of purposes. It’s often used to promote substandard or fraudulent products and services, such as those making outlandish claims that appeal to human desires. It might promise sure-fire ways of seducing women or losing weight. In purchasing the offer, you’ll generally find it doesn’t work as promised. As we’ve discussed, it’s also used as a communication method for social engineering ploys. The message may contain links to bogus sites that automatically download malware, a site where you’re fooled into providing login credentials or personal and financial information, or contain attachments that are virus infected or install malware.

To get a potential victim to a bogus site, malware may be used to modify your computer. Pharming is the process of being redirected from a legitimate site to one that may be used for phishing information. As we explained in Chapter 1, What is cyber safety?, when you type a URL into the address bar of your browser, it’s translated by a DNS server into an IP address. This information may be saved on your computer in a DNS cache, so the next time you go to the site your computer can resolve the name from previously stored information, rather than having to contact the DNS server again. Unfortunately, if this information is poisoned in some way, like a virus or other malware, you could be redirected to a different IP address, where you’ll be presented with a site that looks like the one you meant to visit, but is designed to fool you into providing sensitive information.

To avoid the problems of SPAM, it’s important not to open unexpected or suspicious emails, and don’t click any links within them. As we discussed in Chapter 4, Email safety and security, using the SPAM filters on an email client or site will help detect and remove any known or suspected SPAM messages, so they’re sent to a Junk folder rather than appearing in your Inbox.

Baiting

Baiting is a tactic in which a social engineer will entice you with something that you with something that’s difficult to resist or intrigues you, so you ultimately perform an action that the cybercriminals wants you to take. Visiting a site, you might be offered free music and movie downloads on the condition you provide your login credentials for a certain site. Even if you’re not required to give any information, clicking the link may download a file containing a Trojan virus, or pop open another browser to a site that automatically downloads malware.

Baiting isn’t always done online. A common way to bait someone is to leave a USB flash drive where someone is likely to find it, such as at a bus stop, restaurant, or parking lot. If targeting a particular company, it might be left it by an employee entrance or the smoking area where they take breaks. When a person finds the USB, they may be curious about what it contains, especially if it’s labeled as “Employee salaries” or some other intriguing topic. The person may go back to their desk and plug it into their computer, only to find they’ve installed a hacking tool or some other form of malware. Even if the employee turns the USB in to the IT department it still poses a risk because security may try and open it to find who it belongs to. If the IT department does this, the user may have administrative privileges, meaning the hacker’s tool or malware has full permissions and wider access to the network. By trying to be helpful, the person may have compromised his or her own account, or infected the network.

Hacking

Hacking is a term that’s come to refer to the act of breaking into a computer system. Originally, the term hacker referred to anyone who was a computer enthusiast, and would “hack” away at a keyboard, programming or working on the computer in some other way. A cracker on the other hand was someone who would attempt to crack the security of a system, crack passwords, or perform other actions to gain access. For ease of understanding, we’ll use the terms interchangeably throughout the book.

Unlike what’s shown in the movies, there is no cookie cutter image or motivation behind modern day hackers. There are good and bad hackers, who fall into several distinctive groups:

![]() White hats, who are professional security experts hired by companies, and attempt to penetrate a network to identify problems that can be fixed. After debugging and testing the existing system, they will submit a report showing where the network is vulnerable, and make suggestions for improvement.

White hats, who are professional security experts hired by companies, and attempt to penetrate a network to identify problems that can be fixed. After debugging and testing the existing system, they will submit a report showing where the network is vulnerable, and make suggestions for improvement.

![]() Gray hats, who are individuals having ethical standards that may be altruistic and/or malicious. While a white hat hacker obtains permission from a vendor to find and exploit vulnerabilities, a gray hat may tell the vender that a vulnerability exists but will only provide additional information for a fee or publicize how it can be exploited. Gray hats are also associated with activists who may attack a target believing it’s for altruistic purposes.

Gray hats, who are individuals having ethical standards that may be altruistic and/or malicious. While a white hat hacker obtains permission from a vendor to find and exploit vulnerabilities, a gray hat may tell the vender that a vulnerability exists but will only provide additional information for a fee or publicize how it can be exploited. Gray hats are also associated with activists who may attack a target believing it’s for altruistic purposes.

![]() Black hats, who are what most people tend to think of as hackers, who compromise accounts and systems for malicious purposes and/or personal gain. These are individuals who crack passwords, gain unauthorized access, and may cause disruptions and damage to systems. When a black hat discovers a vulnerability or ways to exploit a system, he or she will generally keep it to himself or herself or share it with other hackers.

Black hats, who are what most people tend to think of as hackers, who compromise accounts and systems for malicious purposes and/or personal gain. These are individuals who crack passwords, gain unauthorized access, and may cause disruptions and damage to systems. When a black hat discovers a vulnerability or ways to exploit a system, he or she will generally keep it to himself or herself or share it with other hackers.

As you can see, the reason someone will hack a system or account varies. Some will try to flex their intellectual skills, and try to see if they’re smart enough to find and bypass security measures. Others may focus on a target for a specific purpose. Hacktivists are hackers who rationalize going after a company or person because they believe they’re doing some good, seeking revenge, or righting some wrong. In this case, the target and purpose is clear, and often publicized to make everyone know the reason. If hackers disapprove of a particular business or government agency, they may attempt to disrupt service so that clients are unable to access their website, or the company is unable to do business.

In the age we live in, hacking is done primarily for the purpose of financial gain or espionage. The goal is profit and information, whether it be personal or on behalf of a client. A company may hire hackers to acquire the corporate secrets of their competition, and government agencies will gather intelligence on other countries or its own citizens. In these cases, the hacker may focus on acquiring specific information about the target, such as looking at the stability of a government, a new product that is being developed, or corporate financial records.

A hacker may focus his or her attack on gaining entry to customer databases. Depending on the company targeted, the information compromised in a data breach could involve personal, financial, medical, or other sensitive records. A hacker may access a company’s database to acquire usernames and passwords, credit card numbers, or other details that could be used for extortion, identity theft, fraud, or shared and sold online, where others can then use the data to commit other crimes. Some of the more serious data breaches in recent years include (Collins, 2015):

![]() eBay, in which 145 million records were stolen, including the login credentials, email addresses, and physical addresses of active users.

eBay, in which 145 million records were stolen, including the login credentials, email addresses, and physical addresses of active users.

![]() Target, in which 110 million records were stolen in 2013, including credit card numbers of customers.

Target, in which 110 million records were stolen in 2013, including credit card numbers of customers.

![]() Home Depot, in which 109 million records were stolen, including credit card numbers and email addresses of customers.

Home Depot, in which 109 million records were stolen, including credit card numbers and email addresses of customers.

![]() JPMorgan, in which 83 million records were stolen in 2014, including email addresses and physical addresses.

JPMorgan, in which 83 million records were stolen in 2014, including email addresses and physical addresses.

![]() Anthem, in which upwards of 80 million records were stolen over a course of several weeks in December 2014, including names, birthdates, Social Security numbers, health care ID numbers, income data, email addresses, and physical addresses (Anthem, 2015).

Anthem, in which upwards of 80 million records were stolen over a course of several weeks in December 2014, including names, birthdates, Social Security numbers, health care ID numbers, income data, email addresses, and physical addresses (Anthem, 2015).

![]() Premera Blue Cross, in which 11 million records were stolen in 2015, including bank accounts, birthdates, Social Security numbers, claims data, and clinical information (Finkle, 2015).

Premera Blue Cross, in which 11 million records were stolen in 2015, including bank accounts, birthdates, Social Security numbers, claims data, and clinical information (Finkle, 2015).

Hijacking/Hacked Accounts

When you hear of hacking, much of what’s reported in the media focuses on instances where organizations have had service disrupted, or major data breaches where records have been stolen. This can give the false assumption that hackers only focus on larger targets. While many attacks are on larger targets, hackers, identity thieves, and other cybercriminals may also set their sights on individuals.

One reason an individual’s account may be hacked is to access details that aren’t public, and only available to friends or the account owner. In 2014, 12% of all complaints the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center (www.ic3.gov) received were somehow related to social media, and in many cases these instances involved gathering information on the person through a compromised account or social engineering (Internet Crime Complaint Center, 2014).

Hacking an account is done to acquire access, but if the person uses the account to impersonate the owner, it’s referred to as hijacking. The attacker has the ability to view your settings, contacts, calendar, and other details that are accessible through the compromised account. If an email or social media account is linked to other sites, they can then logon as you to use various other online services. By posing as you, he or she can also communicate with your contacts to gather more information, or ask them for money or help with an illegal or bogus activity. They may even go through a process of making posts, sending emails, and sharing information to ruin your reputation.

Spammers and other cybercriminals may hijack an account to post messages as you. In doing so, there is a better chance of getting others you know to follow a link, sign up for a service, purchase a product, or enter information into a site designed to acquire login credentials, or personal and financial information. Hijacking the account may be done by guessing your password, using cracking tools, or social engineering tactics to gain access. They may also use malicious software or hide code in a link or page you visit. For example, you might click on a post, and it is then shared by you. In doing so, a spammer is able make it seem that you’re endorsing the site, so that your friends and followers will also click the link.

Someone using social engineering may pose as you to gain the trust of others you know. If you don’t already have a social media account, it would appear that you just joined the site, so people wouldn’t think much about adding you as a friend or following you. If you’re already a member, they could make it seem that you’ve ditched your old account in favor of a new one. Once you’re added as a friend, the bogus user posing as someone you know could see any posts and personal information that you haven’t made public.

On Facebook, you’re not allowed to create a fake account and pretend to be someone else. If you find an account where someone is impersonating you or someone else, you can simply go to the person’s profile page, click the button with three dots  , and then click Report. When the form appears, fill it out to report the account as impersonating someone else.

, and then click Report. When the form appears, fill it out to report the account as impersonating someone else.

If you don’t have a Facebook account and want to report something, you can go to www.facebook.com/help/, click Report Something in the left pane, click Don’t Have an Account? in the left pane, and then click on the How do I report a fake account that’s pretending to be me if I don’t have a Facebook account? link. When the section expands, click the link to file a report, and file a report.

Defaced Sites

Another reason that hackers will try and access a website is to deface it, as an online version of vandalism. Just as any other vandal would spray-paint on a wall, a hacker will often deface a site for “fun,” as part of a larger attack, or as a form of protest by hacktivists. They may change graphics, or modify text, or even sign their work by adding an alias that identifies them. The attack might bring attention to an issue being protested, embarrass a targeted organization, and can have a negative effect on a company’s business. As a visible sign that the site was hacked, existing clients and potential customers are shown that the site is insecure. To see examples of various defaced sites, you can visit Zone-h (www.zone-h.org), click Archive, and then click on the mirror link beside an entry to see what the site looked like after being defaced.

Common Methods

While movies and TV shows tend to show a person sitting at a computer and miraculously penetrating a network with a few keystrokes, hacking often involves research, skill sets, the right tools, and time. This isn’t to say that there aren’t times when opportunity presents itself: a computer with no security might be on an open Wi-Fi network, the wrong permissions applied to a folder allow everyone access, or mistakes in a seemingly secure site allow entrance to areas that are supposed to be reserved for members. While such things happen, most times you’ll need to discover what’s available, what’s vulnerable, and find the best way to get in and out without being detected.

Reconnaissance is the first step a hacker will take, where they try to gather as much information as possible about a target. Often, a hacker will begin with passive reconnaissance, which doesn’t involve direct interaction, is harder to detect, and doesn’t involve using tools that touch the target’s site, network, or computers. Some of the ways you might do passive reconnaissance include:

![]() Search engines, which may reveal documents with the names of a Virtual Private Network (VPN) the company uses, vendor documentation mentioning that the target is a client using certain products (routers, software, etc.). In doing this, you may get information on the company’s remote access, and see cache pages that allow you to stay passive.

Search engines, which may reveal documents with the names of a Virtual Private Network (VPN) the company uses, vendor documentation mentioning that the target is a client using certain products (routers, software, etc.). In doing this, you may get information on the company’s remote access, and see cache pages that allow you to stay passive.

![]() Job advertisements, which can reveal contact information, requirements to know certain software or equipment that may have vulnerabilities that can be exploited, and so on.

Job advertisements, which can reveal contact information, requirements to know certain software or equipment that may have vulnerabilities that can be exploited, and so on.

![]() LinkedIn and other sites where employees have identified their involvement with a target.

LinkedIn and other sites where employees have identified their involvement with a target.

![]() Whois sites (like www.who.is) that provide the names of servers, IP address ranges, the names of administrators, email addresses, and so on.

Whois sites (like www.who.is) that provide the names of servers, IP address ranges, the names of administrators, email addresses, and so on.

![]() Wayback Machine (www.archive.org) to see past versions of a website, allowing you to review the target’s site, see contact information for employees, and even content that may have deemed a security risk and removed from the current site.

Wayback Machine (www.archive.org) to see past versions of a website, allowing you to review the target’s site, see contact information for employees, and even content that may have deemed a security risk and removed from the current site.

Once you’ve learned what you can do without touching a site or network, a hacker will move onto active reconnaissance, which involve interaction with a target and could be traceable. For example, a hacker may call or talk to employees, visit their website, or other actions in which they touch the network as a normal user. After gathering everything you can on a company, its infrastructure, personnel, and other details that can help you gain access, you should have a good idea of the company’s structure and network, and ready to move onto other steps:

![]() Scanning, where you try and identify what hosts are live and their purpose on a network. The hacker might use the PING command to see what servers are running, or use port scanning software to find weaknesses like open ports or ways to bypass firewalls. In doing so, he or she may throttle the scan so its slow pings and scans hide in the normal network traffic, and isn’t easily detectable.

Scanning, where you try and identify what hosts are live and their purpose on a network. The hacker might use the PING command to see what servers are running, or use port scanning software to find weaknesses like open ports or ways to bypass firewalls. In doing so, he or she may throttle the scan so its slow pings and scans hide in the normal network traffic, and isn’t easily detectable.

![]() Service Enumeration, where you identify the services running on a server, and determine any vulnerabilities they might have.

Service Enumeration, where you identify the services running on a server, and determine any vulnerabilities they might have.

![]() Assess Vulnerabilities, where you identify vulnerabilities in an app, site, or network. You might use a vulnerability database, knowledge bases, and a vulnerability scanner like OpenVAS (www.openvas.org) to scan a system and provide a report.

Assess Vulnerabilities, where you identify vulnerabilities in an app, site, or network. You might use a vulnerability database, knowledge bases, and a vulnerability scanner like OpenVAS (www.openvas.org) to scan a system and provide a report.

![]() Exploit Vulnerability, where you either find an existing exploit or develop a new one that can take advantage of vulnerabilities you’ve discovered.

Exploit Vulnerability, where you either find an existing exploit or develop a new one that can take advantage of vulnerabilities you’ve discovered.

At this point, the hacker is finally at a stage where he or she can use the gathered information to attempt breaking into a system or site. The method used will depend on the skill level of the hacker, and what’s easiest and makes the most sense to achieve their goals. For example, if they can get a username and password for an FTP site from a list or through social engineering, they might logon as an authentic user, and then modify or upload web pages so the content is different. If they’ve accessed an administrator account, they have full control of the server or system. If not, they may try to exploit vulnerabilities they’ve found to elevate their privileges to this level.

A hacker’s goal may be to roam the folders and file structure of a server, hoping to find documents and data sources that make their expedition fruitful, but they may not even need to go this far. If a Web developer has poorly coded an application, an administrator hasn’t set permissions properly, and/or security is ineffective, a hacker might be able to do what he or she wants using forms that accept user input or URLs that accept parameters.

Depending what the hacker hoped to achieve, he or she may leave a site so it appears untouched. Any evidence of what was done is cleaned up, permissions are reset, and log files are deleted. The hacker may install a rootkit (which we discuss later) or other malware; he or she may create fake accounts or backdoors that will allow him or her future access. By the end of it, administrators and users may be fooled into believing nothing’s happened, and they’re safe.

Despite the appearance, a hacker might modify links to spread malware or redirect users to a site they control. Click jacking is a method of adding a hyperlink to clickable content. You might visit a page, and a popup window appears that you try and close by clicking an “X” button. Because the link’s been modified, clicking it may actually download a Trojan Horse, transfer money from an account on the site you’re visiting, send you to another site to gather information from you, or some other action you didn’t expect.

A variation on clickjacking is likejacking, where you’ll see a post or status update on Facebook.

Facebook is a common venue for clickjacking, where it often takes the form of likejacking. A post or status update may promise a video or have an intriguing or scandalous draw, such as saying “OMG This GUY Went A Little To Far WITH His Revenge On His EX Girlfriend.” When you click on it, you might be asked to like or share the post before you‘ve even seen it, presented with a fake CAPTCHA or a link that asks you to take a test to prove you’re human. However, these aren’t actually challenges to prove you’re not a robot. Links and buttons on the page will run code to share or like the posts, distributing the spam to others viewing your posts. These scam posts are often used to gather user information, and may redirect you to other spam, phishing, or other malicious websites.

While hacking a site may seem covert, many hackers will post information about it on the Internet. Details of the hack, samples of data, or links to a complete dump of the database may appear on sites like Pastebin (www.pastebin.com), allowing others to view and download the data. Other sources of finding hacked data include Internet Relay chat, tweets about new dumps on Pastebin through Dump Monitor (@dumpmon), or Twitter accounts belonging to a person or group responsible for the data breach. This shares the information with other cybercriminals, who may then use the data to commit other crimes.

Doxing is another practice of sharing information acquired through hacking and other means. Dox is a homonym for docs (i.e., documents) and involves uploading sensitive documents or a dossier of information onto the Internet. For example, in March 2013, the personal and financial information of numerous celebrities were posted on a site called Expose.su. Some of the victims included FBI Director Robert Mueller, Kim Kardashian, Hillary Clinton, Mel Gibson, Ashton Kutcher, and others. Web pages on the site displayed such information as their full names, birthdates, Social Security numbers, current and previous addresses, phone numbers, and copies of a credit report. It was found that while some details on the site were false, other information was accurate.

Groups

While hackers may work alone, there are informal and organized communities of hackers who work together and share information. Those involved include elite hackers with programming and database skills, script kiddies who use other people’s scripts and instructions because they lack the expertise to do it themselves, and those who fall in between who are developing their skills and evolving into a more sophisticated threat. For those involved, it may provide support, a sense of belonging, and a way for new hackers to find mentorship.

While members of a group may know each other, other groups like Anonymous have no central leader and many members may only know each other through online interactions. These groups may use message boards, Twitter, and other forums to share resources and information. In joining together, a group of hackers will coordinate efforts so that they understand their target(s), type of attack, and timing of what events are to occur. This allows them to engage one or more targets effectively in large campaigns or operations (ops).

Inside jobs

Not every attack originates from an outside source. Private data becoming public, unauthorized access being given, and other threats can be caused by malicious or careless users in an organization. According to a report from Intel, 43% of data loss was attributed to those inside an organization; half of which was intentional, while the other half was accidental (Intel Security, 2015).

The simple fact is that in any organization mistakes happen. A person may send confidential information to the wrong person or erroneously post classified information on a public site. For example, in December 2015, a configuration error resulted in 140,000 records on a Southern New Hampshire University database being exposed to the public (Ragan, 2016). Other types of accidental loss may involve situations where a computer, laptop, or other device or storage media is discarded or lost. Such an incident occurred in November 2015, when staff at the Indiana University Health Arnett Hospital realized an unencrypted flash drive was missing. Spreadsheets on the drive contained information on 29,000 patients, including their names, birthdates, phone numbers, and medical information like diagnoses and treating physicians (Indiana University Health, 2015).

Where insider threats are particularly dangerous is when a breach occurs because of a malicious user. While a lost USB drive may never be found and an exposed database may never be discovered, someone has a reason for stealing information. As we discussed in Chapter 1, What is cyber safety?, when Edward Snowden had access to top secret documents, he took it for the purpose of leaking it online. A cybercriminal might acquire a position to have access to data, while a disgruntled employee may see an opportunity to sell it or leak it.

Even though no one has ever attacked a site or system, the results of an accidental or malicious data breach can be the same. It can damage confidence in an organization, resulting in a loss of business, and threatens the confidentiality and privacy of customers. Sixty-eight percent of data breaches were serious enough that the company public disclosure was required or had a negative financial impact on the business (Intel Security, 2015). Regardless of how the information gets out there, the damage is done and the cost can be high.

Low tech

Some of the best methods to get a person’s password are the low-tech ones. As we saw when discussing social engineering, it’s often easier to simply get a person to give you what you want. In addition to the methods we’ve discussed, there are a number of other tactics that can give a cybercriminal access to what they want.

Shoulder surfing involves looking over someone’s shoulder to see what they’re typing. If you have a clear view, and a good memory, you can watch them type and then use what you’ve seen to gain access. If someone can see your PIN as you use an ATM or a debit/credit card payment machine, all they need is your card. For situations like entering a code for a rented locker, unlocking the screen on a phone or tablet, or other single-factor authentication, or typing in a username and password, they only need the PIN or password. To avoid becoming a victim, ensure that any usernames and passwords are shielded as you type them.

Modern technology has made it more difficult defending yourself against shoulder surfing. While you should be wary of anyone behind you or nearby, who may be watching what you’re doing on a keyboard or screen, you probably won’t notice someone watching you over a closed circuit security camera or watching from a distance with binoculars. Therefore, even though no one is in sight, don’t assume no one is watching.

Another useful tactic is dumpster diving, in which a person simply goes through your trash trying to get a hold of telling information. If it’s a business’ garbage, they may find printed maps of the network infrastructure, billing records, manuals, or employee names. This could be useful for social engineering, or (if someone threw out a sticky note with a password) hacking. If it’s your home garbage, they may find preapproved credit cards, a bill with account numbers, or other information to steal your identity. To avoid being a victim, you should shred any documents with sensitive or personal information, as well as ID, and financial cards.

If a hacker wanted access to the building so they could have direct access to employees, computers, and other devices, they might tailgate someone who works there. Tailgating involves following a person into a restricted area. The person may say that they forgot their keycard at their desk and fumble with a number of things to appear as if they’re having trouble finding their door card. If it was cold or raining, they might simply scurry inside behind you, complaining about the weather. Since people often want to be helpful, and don’t commonly challenge others if they appear confident and as if they belong there, tailgating is a simple and effective way of gaining entry.

Once a person is in a restricted area, he or she may have better access to a company’s information and network. While the Wi-Fi and network wall sockets in a public area may be limited, a hacker may find fewer restrictions plugging their laptop into a free wall socket in an office. The hacker may also see confidential documents on desks, usernames, and passwords that someone’s written on a sticky note and attached to a monitor or under a keyboard. They can also ask if they might use someone’s laptop or computer for a moment to check something, giving them the ability to install a program they’ll use to hack the system remotely. By giving people the benefit of a doubt, you’ve helped them in their attack.

Tools

There are a variety of tools a hacker may use to gain access, disrupt service, or damage systems. In many cases, a hacker may use the same ones an IT professional would use to analyze network problems and other issues. There are also tools that are specifically designed for the purpose of cracking security and causing problems.

Botnets and Rootkits

Rootkits are tools that may be installed on a computer to give a person elevated privileges to a system and/or to install other software. The rootkit may be installed automatically by hiding it in other software you’ve downloaded, as a Trojan horse, or installed manually once a hacker’s gained access to your system. Once installed, it may create a backdoor that gives a hacker remote access to your computer, install other malware, or install bots (small programs designed to perform a specific task).

Bots aren’t always malicious, as seen by spiders or crawlers that are used by search engines to access websites and gather information about what content is on a site. Unfortunately, the ones that aren’t innocuous may be designed to access accounts, or determine what downloads are on a site so malware can be created that’s disguised as programs that site offers. Another kind of bot is a spambot, which gathers valid email addresses, so mailing lists can be created to send SPAM. Bots are particularly dangerous when they’re deployed to large collections of computers, called botnets. Once a computer is infected, the bot can lay dormant until an attacker chooses to activate them. At this point, the attacker has control of your computer (now called a zombie) and all the other computers in the botnet (also called a zombie army). The attacker can send a signal to have these computers distribute viruses, or send messages to a particular server in a coordinated attack called a Distributed Denial of Service attack. Because the server gets so many messages from the zombie army, it can’t serve legitimate requests to provide a web page or send-and-receive emails. By flooding the targeted server with traffic, the websites and services it provides become inaccessible and the server may crash.

Password cracking

Despite improvements in authenticating a user, passwords are still a common method of determining if a person or process is supposed have access. While someone may try and crack your password manually by guessing and/or using social engineering tactics, there are also tools that will automatically try combinations of letters, numbers, special characters, dictionary words, check for patterns, and other methods to determine the password. Even if a password is encrypted, it doesn’t mean that it can’t be cracked. A brute force cracking tool may try millions of combinations per second until the hacker gives up or the password is finally discovered.

Password cracking tools are often associated with hacking an account on a site, app, or computer, but there are also ones designed to crack the encryption keys used on Wi-Fi networks. Some of the password-cracking tools that may be used include:

![]() John the Ripper (www.openwall.com/john/)

John the Ripper (www.openwall.com/john/)

![]() Cain and Able (www.oxid.it/cain.html)

Cain and Able (www.oxid.it/cain.html)

![]() AirCrack (www.aircrack-ng.org)

AirCrack (www.aircrack-ng.org)

Because the tool goes through a calculated method of guessing passwords, the time it takes to crack a password varies. The strength of the password, whether encryption is used, and whether there is a limited number of attempts before the account is locked out are all variables in this. In August 2014, Apple’s cloud services called iCloud was hacked, resulting in almost 500 private images of celebrities, including those with nudity be stolen. The accounts were accessed using a combination of spear phishing and brute force attacks, and Apple later patched a vulnerability that allowed unlimited attempts to guess usernames and passwords (VoVPN, 2015). Such a vulnerability isn’t unique. When AppBugs (www.appbugs.co) randomly tested 100 popular apps, they found that 53 of them allowed unlimited logon attempts, meaning a hacker could try over and over again to guess the password without being locked out (AppBugs, 2015).

Another way to get someone’s password is to use recovery tools. In using recovery tools, you’re able to do such things as see the passwords saved on a person’s computer, such as those used in email clients and ones saved in the browser, as well as view other information and restore data that may have been deleted.

Keylogger

Keyloggers are programs that record what you type, logging each keystroke. Some provide the ability to record mouse clicks, what programs you’re using, and may even take screenshots at regular intervals. They can be installed manually or automatically without your knowledge, such as by inserting a flash drive into a USB slot or through a rootkit. Once it’s on your computer, someone can discreetly monitor everything you’re doing. The keylogger may save the recorded keystrokes on your machine (such as to a local or external drive, or flash drive), to a remote location (such as sending it to an FTP site), or emailed.

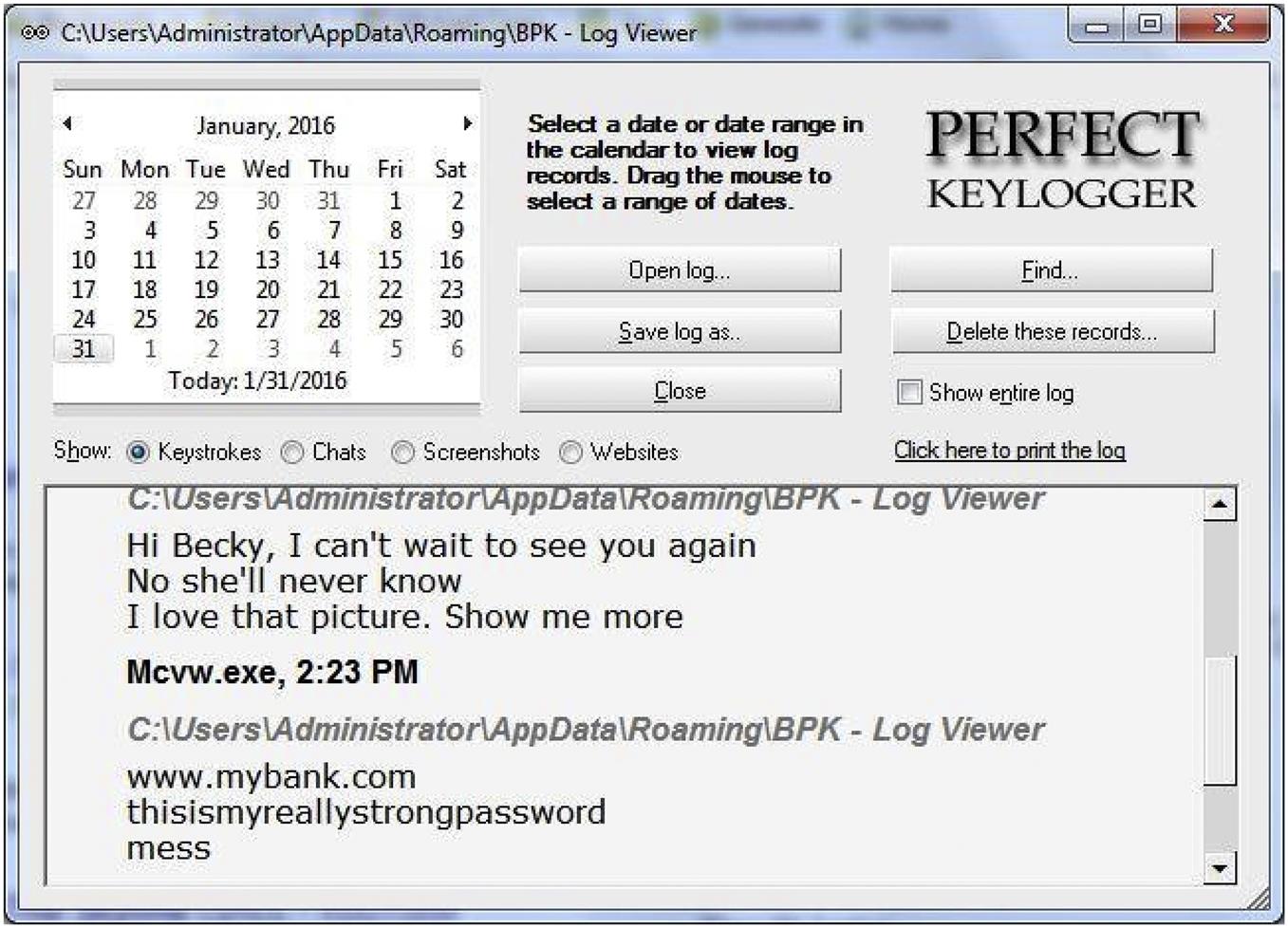

As seen in the Fig. 5.1 (www.blazingtools.com/bpk.html), Perfect Keylogger provides an easy-to-use interface that allows you to navigate through different dates. Once you’ve selected a particular date in question, you can then choose to see the text someone typed on their keyboard, chats, websites they visited, and screenshots of their activity. If you’re using it to monitor someone, it also includes useful date and time stamps to show when the person did something.

As we’ll see in Chapter 10, Protecting your kids, and Chapter 13, keyloggers can be useful in situations where you want to monitor someone’s activity, such as when your child is using the Internet. However, in the hands of a cybercriminal, it can be a vital resource in seeing the usernames and passwords someone typed, the sites those credentials are used for, and other data that may be used for identity theft, blackmail, fraud, and countless other crimes.

Realizing Any Site Could Be Hacked

Regardless of how diligent you are in securing your own computer and devices, data can reside on systems that you rely on others to protect. Being careful of the kinds of information you provide is important, and certainly minimizes the risk, but despite your efforts you do need to accept that some things are out of your control. There is no guarantee that a site won’t be hacked, because any site or system could be.

Without a doubt, the most sensitive data you own is stored by the government, but even their systems aren’t impenetrable. In May 2015, the IRS discovered it was hacked through a “Get Transcript” Web application on their site. It resulted in 330,000 taxpayer accounts being accessed (Phillips, 2015). In June 2015, a separate hacking incident resulted in one of the largest breaches of government data. When the United States Office of Personnel Management was hacked, 21.5 million records were stolen. Most of the data belonged to those who’d been subjected to government background checks, and consisted of personally identifiable information like Social Security numbers, birthdates, places of birth, addresses, financial histories, and even fingerprints (Hirschfeld Davis, 2015). Since there’s no way to avoid filing income tax returns or getting background checks for employment and volunteer work, there’s no way of avoiding your information being in such systems.

Because any site could potentially be hacked, it doesn’t mean that a hacked site should be considered off limits and never used again. Once a site or system’s compromised, you should look at how the business, agency, or organization has handled the breach:

![]() Did they admit the breach occurred, admit any fault, and accept responsibility? Customers should be notified and told what data may have been accessed.

Did they admit the breach occurred, admit any fault, and accept responsibility? Customers should be notified and told what data may have been accessed.

![]() Are they transparent? They should provide details of how it happened, what they’ve done to mitigate the problem, and what they’re doing to prevent it from happening again.

Are they transparent? They should provide details of how it happened, what they’ve done to mitigate the problem, and what they’re doing to prevent it from happening again.

![]() What are they doing for you? They should provide solutions for affected customers and educate them so they understand steps to take. For example, when the IRS was breached, they offered free credit monitoring to those whose accounts were breached.

What are they doing for you? They should provide solutions for affected customers and educate them so they understand steps to take. For example, when the IRS was breached, they offered free credit monitoring to those whose accounts were breached.

![]() Are they providing updates? While it’s important to notify customers, and they may have released a press statement about the data breach, it’s important to provide updated information. When Anthem was hacked in 2014, they setup a site at www.anthemfacts.com to keep customers informed and understand what help was available.

Are they providing updates? While it’s important to notify customers, and they may have released a press statement about the data breach, it’s important to provide updated information. When Anthem was hacked in 2014, they setup a site at www.anthemfacts.com to keep customers informed and understand what help was available.

Until you have some certainty that their systems are secure, don’t use the site or enter any additional information. If they provide a service you need, contact them and ask about alternatives. For example, if it’s your insurance company, ask if there are alternate ways of submitting your claim. Once they’ve taken every possible step to fix the problem, and updated or upgraded their security, you can decide whether the site is worth visiting again.

Protecting Yourself

While you have no control over whether a site is secure, or whether a Web developer has properly coded and sanitized user input, there is protection on the user end. As we’ve discussed in this and previous chapters, you can protect yourself by:

![]() Not clicking on unfamiliar links, such as those sent to you in email, which may download malware or take you to phishing sites.

Not clicking on unfamiliar links, such as those sent to you in email, which may download malware or take you to phishing sites.

![]() Using encrypted connections, such as those using HTTPS to transfer data across the Internet, avoiding unencrypted Wi-Fi, and using the strongest possible encryption on your home network.

Using encrypted connections, such as those using HTTPS to transfer data across the Internet, avoiding unencrypted Wi-Fi, and using the strongest possible encryption on your home network.

![]() Running a firewall to protect the machine from hacking attempts.

Running a firewall to protect the machine from hacking attempts.

![]() Updating antivirus/malware software. Such security can block hacking and phishing attempts, prevent the download of malware, and remove malware as it’s detected.

Updating antivirus/malware software. Such security can block hacking and phishing attempts, prevent the download of malware, and remove malware as it’s detected.

![]() Keep your computer and other devices updated, so they can’t be harmed by known exploits.

Keep your computer and other devices updated, so they can’t be harmed by known exploits.

Using up-to-date browsers also provides better security when using the Internet. Modern browsers will make use of whitelists of trusted sites and blacklists of sites that are known or suspected of being used for phishing or other malicious purposes. For example, on Chrome, you can do the following to turn on safe browsing:

1. Click on the Settings icon in the upper right-hand corner

2. Click on Show advanced settings

3. Ensure the Protect you and your device from dangerous sites checkbox is checked. If not, click on it so it appears checked.

Once turned on, if you try to browse to a site that’s known to be dangerous, you’ll instead be presented with a screen that warns you that the site contains malware, is suspected of phishing, or may be otherwise harmful. With this turned on, you’ll also receive download warnings, such as when Chrome blocks you from downloaded a virus infected or otherwise unwanted file.

Firefox also blocks harmful sites and attempts to install browser add-ons. Once you visit a site, it will see if it’s on a blacklist of sites to be avoided. To ensure this protection is turned on:

1. Click on the Settings icon in the upper right-hand corner

3. When the Options dialog box appears, click on the Security icon at the top

4. Ensure the following checkboxes are checked. If not, click on the checkbox so it appears checked:

a. Warn me when sites try to install add-ons

Similarly, Internet Explorer 8 and higher provide a SmartScreen Filter. When turned on, Internet Explorer will check a site you visit and files you attempt to download against a list of reported sites and programs that are known to be unsafe. It will also analyze pages you visit to see if it has characteristics that are suspicious, such as those used for phishing. If you do try and visit such as a site, you’ll see a page showing you’ve been blocked. To turn on the SmartScreen Filter:

An added measure of security to protect you from cross-site scripting, clickjacking, and force the browser to use HTTPS is NoScript Security Suite (www.noscript.net). NoScript is a Firefox extension that blocks JavaScript, Java, Flash, Silverlight, and other plugins that can be potentially harmful. Unless you’ve added the site to NoScript’s whitelist, the active content on a site is blocked.

Portable tools

Part of dealing with problems is being prepared before they happen. That’s why you need to have antivirus/antimalware installed to remove any malicious programs before they’re installed, and regularly backup devices before there’s a need to restore the data. In a situation where malware a rootkit or other malware has slipped past the antimalware installed on a machine, you may need to use additional tools and find it useful to use portable ones that can be installed on a flash drive. When your antivirus wasn’t able to fend off a particularly new and nasty infection, these can help. Some of the tools available include:

![]() Sophos Anti-Rootkit (www.sophos.com/en-us/products/free-tools/sophos-anti-rootkit.aspx)

Sophos Anti-Rootkit (www.sophos.com/en-us/products/free-tools/sophos-anti-rootkit.aspx)

![]() Malwarebytes Anti-Rootkit (www.malwarebytes.org/antirootkit)

Malwarebytes Anti-Rootkit (www.malwarebytes.org/antirootkit)

![]() ClamWin Portable (portableapps.com/apps/security/clamwin_portable)

ClamWin Portable (portableapps.com/apps/security/clamwin_portable)

![]() VIPRE Rescue (www.vipreantivirus.com/support.aspx)

VIPRE Rescue (www.vipreantivirus.com/support.aspx)

![]() Spybot-Search & Destroy Portable (www.portableapps.com/apps/security/spybot_portable)

Spybot-Search & Destroy Portable (www.portableapps.com/apps/security/spybot_portable)

Scams

A scam is a scheme that’s intended to defraud or trick you, generally as a dishonest attempt to obtain money or something else of value. As we discussed earlier in this chapter, a person or group may send out unsolicited messages through email, instant messages, chat rooms, letters in the mail, phone calls, and other methods of communication that allow them to make contact with a potential target. While we’ll discuss a number of different scams throughout this book, as you go through them, you’ll find elements that help you recognize them as swindles and cons.

Advanced Fee Scams

While scams may use the latest technologies, they’re often based on much older methods of conning people out of their money. An old scam that goes back to the 16th century is the Spanish Prisoner, which originally involved gaining a person’s confidence and telling them that they or someone else was wealthy and being held prisoner. By raising a ransom, the wealthy person could then be released, and would reward his or her benefactor(s) with a generous reward. In some cases, there was an added bonus of promising the prisoner’s daughter would marry the benefactor, meaning that you would now be a member of a family with wealth and status. Once you’ve paid, the con artist would either disappear or ask for more money, continuing on until you had nothing more to give or refused to pay.

Over the centuries, the scam has been adapted and incorporated methods of reaching a wider audience. In the 19th century, letters postmarked from Spain would promise rewards for raising money to release a wealthy prisoner, or assure you a cut of the money if you raised funds to pay, or bribe a court official to release baggage containing hundreds of thousands of dollars. Today, scammers will send bulk email or hijack a social media account to appear as someone you know, all to entice you into wiring money as an advance fee that will result in a higher return. It may say that you’ve won a lottery in another country, and need to pay taxes and fees. Others might promise a share of the money in an overseas bank account containing millions of dollars, if only you can help pay the fees to have it released.

Rather than originating in Spain, the scammer may be (or claim to be) from anywhere in the world. Because a number of the scam emails will mention a Nigerian prince, or claim a connection to Nigeria or another West African country, the scam is often referred to as a “Nigerian 419 scam.” As we’ll see in this and other chapters, there are a number of variations to scams involving an advanced fee.

Intimidation and Extortion

Not every scam is an exercise in duping someone, so they’re fooled into giving into a person’s wishes. Intimidation and extortion scams are designed to frighten and/or coerce a person into giving into a scammer’s demands. The FBI’s 2014 Internet Crime Report notes that these kinds of scams have resulted in people suffering a total loss of $16,346,239, with men and women over 60 suffering the greatest losses (Internet Crime Complaint Center, 2014).