What is cyber safety?

Abstract

This chapter introduces the reader to the basics of cyber safety. In it, we discuss privacy, false or misleading information on the Web, common terms and abbreviations they’ll encounter, and other elements they should be aware or wary of.

Keywords

Cyber safety; slang; privacy

No matter where you go or what you do, safety should always be the primary concern. Any experience becomes a bad one when you or your property is harmed, lost, or in danger. Just as this is true in the real world, it’s also true when dealing with cyberspace. Regardless of whether you’re new to the Internet or a virtual expert, we’ll guide you on how to protect yourself online and off.

What Is Cyber Safety?

Cyber safety is the process of using the services and resources of the Internet in a safe and secure manner. It not only involves protecting your data, but also your personal safety. The goal of cyber safety is to safeguard your computer, personal information, and loved ones from attacks and other potential threats. By using the technology in a safe and responsible manner, you’ll minimize the risks by managing them.

Why Is It Important?

The world is a dangerous place, both on and offline. In the physical world, we put locks on doors, use alarm systems, buy insurance, and take other steps to prevent ourselves from becoming victims. It doesn’t mean we’re paranoid in protecting our assets and families, just that an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. It’s better to stop a problem before it starts than deal with the ramifications afterwards.

The combination of the safety concerns of the physical world and the new risks presented in the virtual world complicate the safety concerns you face when dealing with the Internet. Just like any property, your computer or mobile device might be stolen, lost, or damaged in some way, but connecting it to the Web also means you can be exposed to malware, viruses, hackers, and other threats. While there are thieves, vandals, pedophiles, bullies, and other unwelcome criminal elements in your city or town, the number of people who can be a threat to you exponentially increases with the population of Internet users. Because you’re interacting with more people, using new tools, and visiting sites throughout the world, the number of threats you’ll encounter also increases.

This information isn’t meant to scare you from going online, but is intended to introduce you to potential threats and ways to protect yourself from those threats. There are many ways to mitigate problems, defend yourself, and decrease the likelihood of online risks. Remember, you don’t buy a smoke detector because there will be a fire; you get it because one could happen and you want to prevent serious damage. In the same way, we’ll show you how to install software, configure settings, and make changes to how you conduct yourself online to help prevent potential damage.

What Is the Internet?

When people talk about the Internet, they often refer to it as a single entity. This is reinforced when they hear other terms like The Web or “The Cloud.” The Cloud reference comes from the way that the Internet is depicted on network diagrams and flowcharts, which uses an image of a cloud to represent the Internet without showing its actual complexity. In reality the Internet is a complex network of devices that communicate with one another to send your requests or data from point A to point B. When you search Google for cute kittens, this complex system is able to scour its voluminous index of the Internet in fractions of a second and return to you all the cute kitten pictures you could ever want.

From this, you can see how your data may come into contact with numerous devices and programs in this complex Web of computers, cables, and other equipment.

In most cases the system described above consists of actual machines in a physical location but cloud computing has changed that. With cloud computing your information may be hosted at sites all over the world instead of in a group of physical servers. Unfortunately, this means you never know where your email, attached files, or other data is being stored. While this might not seem an issue at face value, it is problematic when you realize that some countries have less stringent data protection and privacy laws than others.

When you visit a site, data is transmitted between the client and server, allowing you to interact with others and/or access content like Web pages, code in pages that perform some function, online apps, file sharing, online games, and so on. Some of the common online threats you might face in doing this include:

Keep the Faith

You might be feeling a little overwhelmed at all the potential threats that are out there, or thinking that you’re ill-equipped to deal with them. Don’t worry. While many of the articles and news reports sound like someone carrying a sign that says “Repent … the end of the world is nigh,” the reality of cyberspace isn’t that grim.

You also might feel unqualified to deal with cybersecurity issues, but don’t feel alone. A 2012 survey found that 90% of consumers have had no training or classes on protecting their computer or information (WeLiveSecurity, 2012).

You don’t need to be a computer expert to protect yourself. What you do need to do is use the tools and resources that experts have provided. There are a vast number of features, settings, hardware, and software available to prevent an attack, protect your privacy, enhance your security, and/or detect and remove anything affecting or infecting your system. You don’t need know everything about computers, but you should know what others have developed to protect you. Everyone feels like an expert on things they know and use regularly but it’s important to focus on learning what’s needed to keep you safe on the Internet.

Paying Attention to What’s Out There

Just as you might read a newspaper to see what crimes are being committed in your city and neighborhood, you should also stay aware of online threats. By paying attention to what the current threats are, you can identify if there are issues that should concern you. Maybe there’s a new setting on Facebook that should be changed, or a particular vulnerability that needs you to update a system. You should regularly review your settings to see if anything is amiss, and keep up-to-date about changes to sites and systems you commonly use.

Not All Information Is Valid

While the Internet is a resource of incredible information, there’s also a lot of garbage online. People are often deceived by urban legends, which are stories that are circulated as if they were true. There are rumors and hoaxes that have been passed around for generations, and those that are new to the Web, specifically dealing with certain popular sites, programs, or software vendors.

If you see a story that’s particularly humorous, horrifying, or unbelievable, try not to share it with others before doing a little investigation yourself. Copy a line or two and paste it into Google. By surrounding this line in quotes, Google will look for that exact phrase. If the story is a hoax, you’ll see a number of results leading to articles that warn it’s false. If you see articles verifying its authenticity, then it’s probably something you’ll want to share with others.

As we’ll see in Chapter 5, Cybercrime, there are also misleading, fraudulent Web pages and email, which are designed to fool you into providing details about yourself, give up your username and password, or convince you to give them money. These are often modern versions of old con games, distributed through the Internet in the hopes of fooling more people. In the same way you can investigate an urban legend, you’ll often find that organizations and individuals have posted warnings about these swindles.

Whether it’s a scam or an entertaining story, don’t fall for them easily. There are a number of sites that focus on urban legends and Internet hoaxes, allowing you to verify the information. These include:

![]() Snopes (www.snopes.com)

Snopes (www.snopes.com)

![]() Hoax busters (www.hoaxbusters.org)

Hoax busters (www.hoaxbusters.org)

Anyone can put up a Web page, create a legitimate sounding social media account, and post and share information that’s bogus. By checking first, you can avoid falling for these false stories.

Think Before You Click

A major risk when using the Internet can be the links that you click. A hyperlink or link is a section of text, image, or area of the page that’s activated when you click or hover your mouse over it. Clicking the link may take you to another section of the Web page or document, open a new page or document, download a program or file, run code, or send email. Hyperlinks have been the primary method of navigating the Internet, and have expanded to being used in other programs (such as Microsoft Word, PDFs, etc.).

To make a link more user friendly, it may appear as something that says “Contact Us,” “Download,” or another easy-to-understand word or phrase. HTML or other code in the document informs the program you’re using (i.e., a browser, email client) to perform a specific action. Generally, this code will do what you expect, such as taking you to the page you want. However, on clicking it, it could just as easily take you to an untrustworthy site, download malware or a virus, or perform some other action you didn’t expect.

You should avoid clicking on pop-up ads or links that seem suspicious. If an email seems to come from a phony source or has elements that seem dubious, don’t click any links. If you believe the link came from a known source, such as your bank or a store you shop at, go to the site directly with your browser rather than using the link. You can also inspect most links by hovering your mouse over it. This displays what’s referenced in the link (i.e., a website’s address or code) in the status bar of your browser or email client. Doing so gives you a better understanding of what that link does and where it will take you.

Reading URLs

A Uniform Resource Locator, or URL for short, is another name for a website’s address. URLs are used to instruct Internet clients what resource you want to use on a particular server. It’s important to understand how to read a website address so that you understand where you are, where you’re going, and how the connection is being made.

A URL is constructed of several different parts. Any URL begins with the protocol, which is a set of rules used to determine the communication method that’s used between a client and server. Some of the common protocols you’ll see in a URL include:

![]() http://, which is the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP). This is commonly used to download web pages and associated content from a web server, so it can then be displayed in a browser.

http://, which is the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP). This is commonly used to download web pages and associated content from a web server, so it can then be displayed in a browser.

![]() ftp://, which is the File Transfer Protocol (FTP), and used to download files from Internet servers.

ftp://, which is the File Transfer Protocol (FTP), and used to download files from Internet servers.

![]() news://, which is used to access usenet newsgroups from a news server.

news://, which is used to access usenet newsgroups from a news server.

The next part of a URL is the server you’re trying to access. A domain name is a friendly name that corresponds to the IP address owned by that particular site. An IP address is a unique string of numbers that’s separated by dots, and used to identify computers on a TCPIP network like the Internet. You can think of an IP address like you would your home address. In all the world, there are no two places with your address, city, state, country, and zip code, which is why the mail (usually) is sent to the correct address. Because an IP address like 192.168.0.1 would be difficult to remember and type in a browser, we use domain names that correspond to the IP address. When you type in a URL like http://www.microsoft.com, it goes to a DNS (Domain Name Server) that translates this to the correct IP address, so you can then go to the correct site.

You’ll notice that each domain name consists of a hostname (i.e., the name of the server) followed by a dot, and the domain that it’s a part of. Originally, there were only a few domain suffixes (.com, .org, .net, .mil, etc.), but this expanded to use country codes (.ca, .ru, .tv, etc.), and then expanded further to use market-related or custom domains (.coffee, .dentist, etc.). In looking at this, you’d think that the country codes would indicate the location of a server, but this isn’t the case. It only identifies under what country the site’s owner registered the name.

After the domain name, you may also see a slash followed by another word. This may indicate a particular resource you’re accessing, such as a default web page with the file extension of .asp, .htm, or .html. If you went to www.fda.gov/default.htm, you’re telling the browser to load the web page default.htm on that site. Alternatively, the resource you’re accessing may be in a folder, so the URL may show the path. If you went to www.fda.gov/Food/default.htm, you’re telling the browser to open the file default.htm that’s located in the Food folder on that site. Fig. 1.1 depicts the parts of a typical URL.

Faking sites with URLs

Now that you have a good understanding of how URLs work, we’ll show you how they can be manipulated. Legitimate sites will often use subdomains to split apart a site into logical parts called subdomains. If you started a site called www.myfakesite.com, you might want to split it apart. While your main site is on myfakesite.com, you might have a store on a subdomain called shop.myfakesite.com, or support for using your products on support.myfakesite.com. Each of these are different sites on one or more servers.

Cybercriminals may try and misdirect you by naming a subdomain after a different site you’re expecting to visit. You may get an email about your Amazon account, with a link that goes to amazon.myfakesite.com. When you glance at the URL, you might think you’re on Amazon’s site, but you’re really on a bogus site designed to look like the real thing. As we’ll see in Chapter 5, Cybercrime, this is a common trick to fool you into logging on and “verifying” information.

When reading a URL, read the domain name from right to left. In doing so, you may see a country code indicating its possible location (remember, this isn’t always the case), its name, and any possible subdomains.

Another possible problem you may encounter is when you see URLs that have been shortened. Using a service like TinyURL (www.tinyurl.com) or Google URL shortening service (https://goo.gl/), you can enter a long website address, click a button, and have it shortened to a shorter URL. This is useful when sharing URLs on sites that have character limits, or you’re suggesting people visit a site with an incredibly complex address. When the person clicks on the link, it contacts the service, which then refers your browser to the address you want them to go to. It’s so useful that Twitter and Facebook have their own URL shorteners, so that any tweets containing long URLs are automatically shortened.

The problem with shortened URLs is that you don’t know where it’s taking you. Maybe it’s taking you to a legitimate site, or maybe it’s leading you to a site where malware will be downloaded. To make sure you’re going where you expect, use a site like LongURL (www.longurl.org/) to expand shortened URLs. After entering a shortened URL in the box, click the Expand button to see the full URL. At this point, you can decide to visit the site, or ignore it for safety’s sake.

Privacy

Internet privacy is a growing concern. When you visit a site, save a file, or provide information online, you should be secure in the knowledge that only you and authorized users have access to it. Unfortunately, that’s not always the case.

Expectations and Reality

When you use the Internet, you should take some time thinking about the level of privacy you expect from different sites, how the information you post online is used, and who can see where you go and what’s stored. This will determine the settings you select, the sites you visit, and the browser, apps, and search engines you use.

Many times, your expectations of privacy are clearly outlined on a site, although few people actually read it. Often when you visit a site, there’s a link to a Terms of Use or Privacy Policy page that outlines whether data is shared with third parties and how it may be used. Similarly, when you install an app on your phone or tablet, it will say what personal information and data is being accessed by the app. The problem is that many of us either don’t understand or ignore this information. We want to use the app or site, so we click on an Accept button. Taking the time to read this information will however help you understand your rights, and help set your expectations.

Because of how much they have to gain, advertising firms have considerable interest in Internet privacy issues. Once advertisers understand what you’re looking for, they can focus the site’s ads to sell items and services you’re interested in. This is done in a number of ways, including:

![]() As we’ll see in Chapter 2, Before connecting to the Internet, small files called tracking cookies may be stored on your computer as a means of monitoring the sites you visit.

As we’ll see in Chapter 2, Before connecting to the Internet, small files called tracking cookies may be stored on your computer as a means of monitoring the sites you visit.

![]() Search engines may store information on your searches.

Search engines may store information on your searches.

![]() Online surveys may be used to get you to provide details about shopping habits, etc.

Online surveys may be used to get you to provide details about shopping habits, etc.

Questionnaires and online surveys are useful tools for gathering information, but you should be careful of how much you reveal. You may sign-up with a site to fill out a survey in exchange for rewards, or take it out of interest or concern. In such situations, you might create a profile or sign-in with your real name and email address, which lets the site know who you are and associate you with what’s entered on the survey. If you’ve ever used an online questionnaire to help diagnose a potential medical or psychological issue, it can be even worse since you’ve provided personal, private, and medical information to a group of strangers. If you post comments and questions in a support site afterwards, then knowledge of the medical issue is even more public; it’s visible to anyone who uses the site and possibly accessed in search engines results.

Often, some of the most personal bits of information are facts that we’ve posted about ourselves. Posting your date of birth, address, phone number, where you work or go to school, and other personal details online can expose your private life to strangers. The same applies to information in profiles, online resumes, and albums, which should be set so that only those you trust can see it. When using the Internet, the goal is to keep private information private.

The other issue with privacy comes in the form of governments. While conspiracy theorists said for years that the US government was monitoring telephone and Internet communications, it came to most people’s surprise that there was some truth to it. In 2013, Edward Snowden (a former government subcontractor) leaked top secret documents that showed numerous surveillance programs were being conducted by the National Security Agency (NSA) and other intelligence agencies. Snowden began stealing documents about how the NSA was conducting domestic surveillance on millions of citizens, monitoring their calls, and Internet use. The validity of the information was essentially verified when the US government charged Snowden under the Espionage Act (The Washington Post, 2013).

According to information provided by Snowden, the NSA used a program called PRISM to collect real-time information. While it supposedly only gathers information on American citizens, it apparently wasn’t the only one in use. When you consider that much of the world’s communications goes through the United States, it’s logical to assume that the network traffic being monitored isn’t just the data being generated by its citizens.

While a number of countries have laws and regulations dealing with Internet privacy, most do not. Even when such laws exist, there can be difficulty enforcing them when a citizen is in one country and the server is in another. While international privacy enforcement authorities have cooperated with one another, and even taken initiatives to examine websites, there are so many sites around the world that it’s difficult (if not impossible) to ensure online privacy is being adequately protected.

You are the greatest defender of your privacy. Throughout this book we’ll show you various privacy settings you can configure to prevent others from seeing your data. When using a site, determine if it has a privacy policy, and if there’s contact information for addressing privacy questions or concerns. Similarly, if you’re using an app, read the warnings that inform you of what information will be sent and what will be shared with third parties. If you’re not comfortable with those policies, then don’t bother using the app.

Who Has Ownership?

Just because you posted something, it doesn’t mean it’s necessarily yours. You may have read an article, made a poignant comment, and in posting your thoughts, transferred your rights to them. If an online newspaper, media outlet, or other site has set conditions on being able to review or respond to the article, they may have included a clause of who owns those comments once they’re submitted. The reviews and feedback you give may become the property of the site or blog that you responded to.

When you sign-up for a new account or use a site, you agree to the Terms of Service. The site may say in using the site, you’ve agreed to the conditions, or they may have you click a button to explicitly agree to them. The Terms of Service will explain your rights, and let you know whether you retain ownership of your intellectual property, transfer it to them, or allow them to use it. These conditions should be reviewed periodically just so you’re aware of any changes. Some of the terms you might see on commonly used websites include:

![]() On Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/terms.php), you own all of the content that you post.

On Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/terms.php), you own all of the content that you post.

![]() Although other sites may pull reviews from Amazon (www.amazon.com), you own the reviews you’ve posted.

Although other sites may pull reviews from Amazon (www.amazon.com), you own the reviews you’ve posted.

![]() The New York Times has a different view on user-generated content. They state in their Terms of Service (www.nytimes.com/content/help/rights/terms/terms-of-service.html#discussions) that “you waive any rights you may have in having the material altered or changed in a manner not agreeable to you” and you grant The New York Times or any third-party designates “a perpetual, nonexclusive, world-wide, royalty free, sub-licensable license.”

The New York Times has a different view on user-generated content. They state in their Terms of Service (www.nytimes.com/content/help/rights/terms/terms-of-service.html#discussions) that “you waive any rights you may have in having the material altered or changed in a manner not agreeable to you” and you grant The New York Times or any third-party designates “a perpetual, nonexclusive, world-wide, royalty free, sub-licensable license.”

You may have seen people posting disclaimers on Facebook and Twitter that state any material they’ve created is protected by copyright, is their intellectual property, and belongs to them. However, posting a disclaimer doesn’t override the Terms of Service you’ve agreed to when setting up an account. That being said, it may be advisable to post a disclaimer if you have anything of value posted online, but not because you think the site’s policies may change. If you’re a photographer or an artist, the sale of pictures is your livelihood, and posting copies online may be your way of advertising. Posting a disclaimer may dissuade others from using your content on their own blogs, intranet sites, or other venues.

If you’re using a site where your comments do become the property of someone else, this doesn’t mean you aren’t liable for any derogatory or inflammatory comments made. Posting something that goes against their community standards or user agreement may result in deletion of your account. If you threaten or post statements in relation to some other crime, the site may release it to police so you can be prosecuted.

Another situation where ownership becomes an issue is in the workplace. Many organizations have policies that state anything created with company-owned equipment, during work hours, and/or using their resources becomes their property. Perhaps they don’t want you creating a work-related product and later claim it’s your intellectual property, or they want to prevent you from running your own business from work.

Businesses also commonly have policies that state, because anything with company-owned devices or services is theirs, they have the right to check your work email and the contents of any computer, tablet, or device you use. This means that any emails you send, files you save, or sites you visit are not private. A company may remotely check your laptop or mobile device, log activity, or read through any emails sent or received using your work account.

Where Are Your Files Stored?

You’ve probably realized by now that the location of your data plays a big part in your expectations of privacy. While there are risks saving files to your local hard disk there are serious considerations when they’re stored online, a corporate network, or devices owned by the people you’ve texted, emailed, or sent files to.

If you’ve used any computer or mobile device for a time, you’ve probably sent someone a photo. You might not consider that the photo is now on your device and the other person’s. The other person could now share it with his or her friends, post it online, or do something else that’s out of your control. If either device was lost, stolen, or hacked, the photo is now in the hands of someone else. If the photo was saved to the Cloud, then it’s also on an Internet server. You’re trusting that the storage is secure, anyone who works there won’t access it, and that your account won’t be hacked, meaning another complete stranger might publish it on different sites. As we’ll see in Chapter 8, Protecting yourself on social media, the type of storage you choose will depend on your needs, and how secure it is will often rely on you.

You should be aware of where your data will reside, so you can understand what may happen to it. If you’re a decent, law abiding person, then it’s pretty remote that law enforcement will serve a warrant to search your computer. If files are stored on the Cloud, or data has been entered into a site’s database, it resides on a server. If a government entity decided to seize the servers as part of an investigation, your files and data may not be immune to being searched.

Organizations may shy away from the Cloud for corporate needs is because it isn’t clear where the servers reside, or if they reside in a foreign country. Imagine what would happen if a police department kept criminal records on the Internet, and the server was in another country. Antiterrorism laws in that country might allow their government to have access to the data, or data protection laws there may be lax or nonexistent. Just as a company protects the privacy of customer and client data, you should be concerned about yours.

How Important Is Your Data?

While we’ve talked a lot about protecting sensitive information, you should also consider what the data is and its importance. When looking at what’s being posted or saved online, consider the relevance of the information. Would you really be embarrassed or care if it got out? While your medical and financial information require the highest levels of protection, does it matter if a hacker or the government gets ahold of your Aunt Martha’s peach cobbler recipe?

When saving to the Cloud, sending as an attachment, or posting on social media, look objectively at the information. Try to determine its importance, and how it may affect you if it went public now or in a few years. This not only tells you if it’s suitable to share, but also whether it requires higher levels of protection.

Once It’s Out There, It’s Out There

It’s important to realize that information you post online may be there permanently, or at least what seems like forever. Many sites will keep articles, posts, and other data online indefinitely, allowing others to view what you said or did years later. While this can be useful if you want to look at old pictures or events on your Facebook page, it can be problematic when there’s information you’d rather others not see.

Just because there are laws to protect your privacy, they may be somewhat fuzzy where the Internet’s concerned. For example, credit bureaus and financial institutions can’t reveal details like bankruptcies after a certain number of years, but an article or post that mentions it may be online indefinitely. Newspapers and media outlets regularly report people who are arrested, but rarely tell you the outcome if the case is thrown out of court. You might be charged, but there might never be a follow-up article saying it was all a big mistake. The long-term effects of this can be catastrophic, because there isn’t an expiration date for content on the Internet.

If you’re concerned about your reputation, then you should be careful about what you put on the Web. This not only includes what you’ve explicitly shared with others, but also what’s been stored on the Cloud. While efforts are made to make online storage as secure as possible, it doesn’t mean a server on the Net is impenetrable. In 2014, hackers used phishing and brute force password attacks to acquire the usernames and passwords of people using iCloud (Ars Technica, 2014). The Apple Cloud services breach lead to hundreds of private photos belonging to celebrities being accessed, which were then shared on other sites. When using the Cloud, you’re trusting that the best possible security measures are in place, but that means you’re trusting someone who works for that service to have your best interest in mind, to have made no mistakes, and to have left no security holes in the system.

The same applies to the data you enter into websites. This became painfully obvious to users of Ashley Madison (www.ashleymadison.com), an online dating service for people who are married or in “committed” relationships. In July 2015, hacker(s) calling themselves The Impact Team stole the website’s customer’s data, including personally identifying information (names, addresses), financial information (credit card numbers), and details of their sexual fantasies and interests. The hackers posted this information on Pastebin (www.pastebin.com) when Ashley Madison didn’t meet their demand to shut down the company’s websites. Some of what was posted showed that even though people requested (and even paid) to have their data deleted, it still existed in the hacked servers (The Register, 2015).

As we’ll see in Chapter 11, there are some methods and tools to remove your content from the Internet. You can request it be removed from websites, search engines, and in a number of cases remove them yourself. However, this doesn’t mean that it’s completely gone. Sites may have a backup of files, someone out there has a copy of it, or the sites made your data so it isn’t visible but haven’t actually removed it. What’s the best way to prevent others from seeing something you don’t want them to see? Never post it at all.

Encryption

Encryption is a process of encoding messages so that only those who are authorized to view the data can read it. Without encryption, the message is referred to as plaintext, but when an algorithm is applied the message becomes scrambled and is called ciphertext. There are different kinds of encryption that may be used to protect the data stored on a computer or sent over a network, including:

![]() Symmetric Cryptography, which is also called private-key cryptography, uses a key (which may be a password or digital certificate) to encode the message into ciphertext, and the recipient uses the same key to decrypt it. To use this type of encryption, the same key must be shared among anyone accessing the data. If you and I don’t use the same key, you’ll be unable to decrypt what I’ve sent to you. Common symmetric encryption methods include Advanced Encryption Standard, International Data Encryption Algorithm, and Data Encryption Standard.

Symmetric Cryptography, which is also called private-key cryptography, uses a key (which may be a password or digital certificate) to encode the message into ciphertext, and the recipient uses the same key to decrypt it. To use this type of encryption, the same key must be shared among anyone accessing the data. If you and I don’t use the same key, you’ll be unable to decrypt what I’ve sent to you. Common symmetric encryption methods include Advanced Encryption Standard, International Data Encryption Algorithm, and Data Encryption Standard.

![]() Asymmetric Cryptography, which is also called public key cryptography, uses a private key and a public key to encrypt and decrypt messages and data. While the public key is available to anyone to encrypt messages, the private key is used by the recipient to decrypt the message. Common asymmetric encryption methods include Diffie-Hellman and RSA.

Asymmetric Cryptography, which is also called public key cryptography, uses a private key and a public key to encrypt and decrypt messages and data. While the public key is available to anyone to encrypt messages, the private key is used by the recipient to decrypt the message. Common asymmetric encryption methods include Diffie-Hellman and RSA.

![]() Hashing, in which a unique fixed-length signature is created for a message or data set with an algorithm. Because the signature is unique to the message, even a slight change to its content can create a drastically different hash. It’s different from the previous methods, because once hashed, it isn’t decrypted to its original form. Instead, it’s compared to other data, so you can determine if both hold an identical message. This makes it useful for password verification, digital signatures, and other situations where one message or data set is compared to another, because you can determine if both sets hold the same data. Common hashing algorithms include Message Digest 5 and Secure Hashing Algorithm.

Hashing, in which a unique fixed-length signature is created for a message or data set with an algorithm. Because the signature is unique to the message, even a slight change to its content can create a drastically different hash. It’s different from the previous methods, because once hashed, it isn’t decrypted to its original form. Instead, it’s compared to other data, so you can determine if both hold an identical message. This makes it useful for password verification, digital signatures, and other situations where one message or data set is compared to another, because you can determine if both sets hold the same data. Common hashing algorithms include Message Digest 5 and Secure Hashing Algorithm.

As we’ll see throughout this book, there are many different ways in which encryption is used. In Chapter 2, Before connecting to the Internet, we’ll discuss how encryption is used on networks, like the Wi-Fi network in your home, work, or school. This prevents others from seeing passwords, usernames, and other packets of data being sent to-and-from your computer. As we’ll see in the sections that follow, encryption can be used on your computer to prevent others from viewing your files, and also used on the Internet to prevent others from viewing transactions and other activities between your computer and a secure server.

Encrypting Storage

A simple way to access someone’s data is to plug their storage device into another computer. While removing an internal hard drive from a computer is slightly more difficult and considerably more noticeable than walking off with an external hard drive or USB flash drive, once attached to a different computer, a thief is able to access your files without ever entering an account name or password. This is why file encryption is so important.

Encryption makes any data on a storage device useless to a thief. If one were to steal an encrypted drive, they would only be able to access the data using a key (such as a password), or by using the original computer that encrypted it. There are a number of free and commercial products that can be used to encrypt individual files, folders, or entire hard disks, including VeraCrypt (https://veracrypt.codeplex.com) and CipherShed (https://ciphershed.org/). In addition, some operating systems include features to encrypt local and removable drives.

BitLocker is an encryption tool that’s included with Windows Vista and higher versions. It will not encrypt individual files and folders, but it will encrypt entire drives. This not only includes drives on your computer, but also any external hard drives or USB flash drives you might have. In the following example, we’ll show you how to encrypt an USB stick:

1. Open File Explorer, and in the left-pane right-click on the drive letter for your USB stick.

3. When the wizard appears, click on the checkbox to Use a password to unlock this drive. If you use a smart card, you could also use that feature to unlock the drive, which would require you to insert your smart card and enter your PIN to unlock the drive. If you were encrypting a fixed drive, you would select the option to automatically unlock when you log into Windows. After selecting to use a password, enter a password into the Type your password box, and then type it in again in the Retype your password box to confirm. Click Next.

4. On the How Do You Want To Store Your Recovery Key page, click Save the recovery key to a file. When the Save BitLocker Recovery Key dialog box appears, choose a location to save the file and then click Save. You have the option of using this to print the recovery key (password) when needed.

5. Click Next, and on the Are You Ready To Encrypt This Drive page, click Start Encrypting.

When Bitlocker encrypts the USB flash drive, it will add a program to it called bitlockertogo.exe, which is the BitLocker To Go Reader. This program is used to unlock the drive so you can read the data. If the drive is encrypted with a password, it will prompt you for it, and upon clicking the Unlock button, you’re then able to access the files.

The BitLocker To Go Reader is not required for reading an encrypted local drive, as the BitLocker feature on the operating system will handle this for you. If you’ve encrypted a local drive, and want to move it to another computer, you would need to decrypt the drive before installing it on another machine. To do this, you would right-click on the drive letter, click Turn Off Bitlocker, and follow the prompts.

To see which drives are encrypted on your machine, you can use the BitLocker Drive Encryption program in Windows. In Windows 8x and 10, you would search for “bitlocker” and then click BitLocker Drive Encryption. In Windows 7, click Start, click Control Panel, click System and Security, and then click Manage Bitlocker. Once it appears, you will see a list of your drives, and have the options to turn bitlocker off on encrypted drives, or turn it on when you want to encrypt a nonencrypted drive.

Encrypting mobile devices

In addition to encrypting computers, you can also encrypt mobile devices and the SD cards you’ve inserted for extra storage. It’s common for devices to require you to set a PIN, passphrase, or swipe pattern to unlock your phone prior to setting encryption. If this isn’t set, the options for encrypting SD cards may not be available in your settings. Once you’ve set a PIN, password, or swipe pattern to unlock the screen, you would then go into your Settings menu to encrypt the card.

![]() On an Android phone, you tap Settings, tap Security, and then decide on the option to encrypt an external SD card or Encrypt Device. If you encrypt the device, you’ll need to enter your password each time you turn your phone on, so it can be decrypted. If you have an SD card that you want encrypted, you would select Encrypt external SD card on the Security screen and follow the prompts to either encrypt the entire card, or new files that are added.

On an Android phone, you tap Settings, tap Security, and then decide on the option to encrypt an external SD card or Encrypt Device. If you encrypt the device, you’ll need to enter your password each time you turn your phone on, so it can be decrypted. If you have an SD card that you want encrypted, you would select Encrypt external SD card on the Security screen and follow the prompts to either encrypt the entire card, or new files that are added.

![]() On an iPhone, iPad, or iPod Touch, you would set a passcode to access your phone, which will instruct you that Data protection is enabled.

On an iPhone, iPad, or iPod Touch, you would set a passcode to access your phone, which will instruct you that Data protection is enabled.

![]() On a Blackberry, you would tap Settings, tap Security and Privacy, tap Encryption and then move the slider to the On position for what you want to encrypt. You can select to turn Device Encryption and/or Media Card Encryption to either encrypt the device and/or an SD card.

On a Blackberry, you would tap Settings, tap Security and Privacy, tap Encryption and then move the slider to the On position for what you want to encrypt. You can select to turn Device Encryption and/or Media Card Encryption to either encrypt the device and/or an SD card.

Secure Communication on the Internet

Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) is a protocol used to transmit communications over networks like the Internet, so that any data is encrypted. Sites use SSL to ensure confidential communication, especially in situations when account information, passwords, credit card numbers, financial transactions, or other sensitive information is being sent between you and the server. Email programs and mail servers may also use SSL to ensure that data can’t be captured and viewed during transmission. Some sites also use Transport Layer Security, which is an updated version of the previous standard, and provide the following security measures:

![]() Client authentication, which means that the client can identify the server, and verify that any data being transferred will be secure.

Client authentication, which means that the client can identify the server, and verify that any data being transferred will be secure.

![]() Data encryption, so that any data being transferred will be indecipherable if it’s captured en route. In doing so, the server can decrypt any messages the client has sent, and vice versa, but anyone else would only see it as a scrambled message.

Data encryption, so that any data being transferred will be indecipherable if it’s captured en route. In doing so, the server can decrypt any messages the client has sent, and vice versa, but anyone else would only see it as a scrambled message.

![]() Integrity checks, which verifies that the data hasn’t been altered in any way while in transit.

Integrity checks, which verifies that the data hasn’t been altered in any way while in transit.

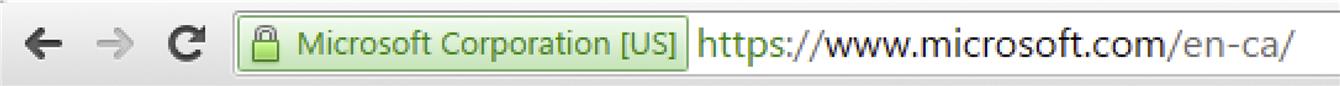

As seen in Fig. 1.2, it’s easy to identify if your browser has a secure connection by looking at the address bar of your browser. If the site begins with https:// then you can see that SSL is being used. Also, to the left of this in Chrome and to the right in Internet Explorer, you’ll see information about the site’s certificate. By clicking on it, additional details are displayed, allowing you to see who verified the certificate, and the type of encryption being used.

It’s important to look at the address bar and see when SSL is being used. Even if you’re using HTTPS to do business on a site, the initial logon to the site may be using HTTP, meaning your username and password will be sent unencrypted. Just imagine the implications of signing onto a banking site, where everything after the initial logon is encrypted, but the username and password may have been captured by an unknown party.

You can force a browser to use HTTPS by typing https:// in front of every URL you enter into the browser’s address bar. You can also install HTTPS Everywhere (www.eff.org/https-everywhere) on your Chrome, Firefox, or Opera browser. Once installed, the browser will try to use HTTPS to connect to any website you visit. If HTTPS isn’t supported, then the browser will try using HTTP.

Monitoring Online Activity

A good way to recognize if you have a security breach is to monitor your online activity. As we’ll see in Chapter 6, Protecting yourself on social media, there are a number of ways to keep track of when someone last logged onto your social media accounts. Some provide automatic email notifications when someone logs in from an unfamiliar machine or unsuccessfully tried to logon. Sites often provide a date and time of your last logon attempt.

If some of the sites you use don’t provide these abilities, then review previous posts you’ve made, and periodically check your account. If you see any changes or unfamiliar activity, change your password immediately.

If there are sites you don’t use anymore, delete the accounts. Even though you don’t use it, walking away from an account without deleting it means the profile information is still there, and so is any content you posted. This means it’s a potential target for hackers and a possible source of intrusion for you.

Monitoring Your Bank Account

It’s common for people to use game systems, apps, and websites to make online purchases. What should be equally common is checking your financial account in the days following a purchase. By routinely logging onto your bank and credit card accounts, you can review past purchases and see if you’ve been overcharged, or charged for items and services you never agreed to buy. It only takes a few minutes to sign-in and look at recent activity, so it shouldn’t be a burden. If you see a purchase you don’t agree with, dispute it and contact the bank or credit card company to report a possible problem.

Identifying the Devices You Use, and Where You Use Them

It’s wise to take an inventory of the devices you have, so you understand what connects to the Internet and what devices you need to manage. By having a list of devices, you won’t inadvertently miss one when you change a Wi-Fi password for your home network, update settings, or when troubleshooting which device may be causing a network problem or security risk. Making a list isn’t that difficult, but it should include any PCs, mobile devices, game systems, smart TVs, or other devices using your home network or the Internet.

When making the list, you should include any important identifying information, such as its make, model, serial number, and so on. This will be helpful if you ever need to report it stolen, and can help police in returning it.

Separating Home and Business Computers

When you inventory which devices connect to the Internet, try and make a distinction between those used for personal use, and those used for work. As we saw earlier in this chapter, businesses often have policies stating that anything on a company-owned machine belongs to the organization. This includes email, files, and any other work you’ve created. Your employer can search any device they’ve issued you, at any point, and without your permission.

Another reason to separate home and business is support. Because your phone, tablet, laptop, or other device is owned by the business, it’s up to them to maintain it. If something breaks, you won’t pay to fix it yourself, but would bring it to your IT department. In doing so, you should be aware that they may inspect the machine, and see any files you’ve saved, email that’s been sent, or browser activity. Depending on what’s on your machine this could be embarrassing or cause problems in your job.

When you use a business device for personal use, the question arises of who’s responsible for any damage. You might find that because you’ve installed personal apps, let your child use it, or done something else related to the problem, you may be responsible for paying for any repairs. Companies often have policies on proper computer use, and violating them may result in you being responsible for any repairs or replacement.

Bring your own device

To lower the cost of paying for new equipment and decrease training, many companies allow you to Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) to the workplace. This can include tablets, laptops, smartphones, and other devices that you pay for, but can use for work-related purposes. When they allow this, the organization will often draft a policy that outlines who’s responsible for repairs, support, and so on. Often, only the business-related elements (i.e., network connectivity, corporate email) are supported. In other words, don’t expect help from the IT department because Angry Birds isn’t working.

Because the device needs to be setup to function with the business’ systems, you’ll need to bring your personal device to the IT department, so they can configure it to work with their email system, access the corporate network, and install any software needed to adhere to keeping their network secure. This may involve configuring the device with passwords, prohibiting certain types of applications from being installed, ensuring that encryption is used, and so on. To ensure this hasn’t changed, they may ask you to bring in the device, so they can audit it.

Although it’s convenient to use your own devices at work, you should really consider what’s happening here: someone is accessing your device, installing software, changing settings, and possibly limiting your ability to manage it. Depending on the security policies, you might be blocked from visiting certain sites, or unable to install certain apps. The company may also give themselves the ability to remotely wipe your device, which may be required if you quit or get fired. If that happens, not only will you lose work-related information and files, but your personal ones as well. Even if you’re not fired, accidents happen, so make sure you regularly back up the device to minimize the loss.

BYOD may also draw you into some strange situations. Many companies have an acceptable use policy, and this may extend to your own device. While it may seem strange having an employer tell you what you can and can’t do with your own device those rules exist to protect both you and the employer from inappropriate or potentially dangerous Internet activities. It may get trickier when you also have your own business and save that work on the device used in the BYOD program at your other job. The employer may challenge you on what data on the device belongs to them, what belongs to other clients you have, and what material is your intellectual property.

If you’re going to bring your own device to work, consider using one that’s only for business use. While it would still give you the benefits of having your own device, it would avoid many of the problems you’ll encounter in a BYOD program, and keep your personal files and activities separate.

Computer Use in Public Places

Not every computer you’ll ever use is yours. You may be using a computer in a school laboratory or one at work, one in a library, or borrow someone else’s phone or tablet. When using any system that’s not yours, you should take steps to prevent your data from being left behind:

![]() Delete any phone number from the recent calls list on a phone you’ve borrowed.

Delete any phone number from the recent calls list on a phone you’ve borrowed.

![]() Don’t save any logon information. If prompted to save a password on the browser, always click no, as this can be used by someone else to later log in automatically. When logging into a website, ensure that there are no checkboxes checked stating you want the site to remember you. Always log out of any websites you visit.

Don’t save any logon information. If prompted to save a password on the browser, always click no, as this can be used by someone else to later log in automatically. When logging into a website, ensure that there are no checkboxes checked stating you want the site to remember you. Always log out of any websites you visit.

![]() Don’t save files locally, as these will remain on the computer.

Don’t save files locally, as these will remain on the computer.

![]() Don’t leave the computer unattended. Walking away from a machine while its logged in may leave sensitive information displayed on the screen.

Don’t leave the computer unattended. Walking away from a machine while its logged in may leave sensitive information displayed on the screen.

![]() You should use InPrivate or Incognito browsing so that details of your browsing activity isn’t saved on the machine.

You should use InPrivate or Incognito browsing so that details of your browsing activity isn’t saved on the machine.

![]() As we’ll see in Chapter 2, Before connecting to the Internet, disable any features that stores passwords.

As we’ll see in Chapter 2, Before connecting to the Internet, disable any features that stores passwords.

![]() Don’t use the computer for anything that may reveal financial or sensitive information. You don’t know if someone installed a keylogger or other monitoring software, which we will discuss in Chapter 5, Cybercrime.

Don’t use the computer for anything that may reveal financial or sensitive information. You don’t know if someone installed a keylogger or other monitoring software, which we will discuss in Chapter 5, Cybercrime.

If you have your own mobile device, you’re probably thinking this isn’t a problem. After all, you’re the only one using your phone or tablet, and you’ve taken all the necessary precautions to secure it. However, even though the device is yours, any public Wi-Fi (such as hotspots in coffee shops, restaurants, and other public places) won’t be under your control. As we’ll see in Chapter 2, before connecting to the Internet, there are risks to using someone else’s Wi-Fi, and steps you can take to protect yourself.

Mobile Devices

A mobile device is any small, portable computing device, such as tablets, smartphones, and other handheld computers. Even though they’re small, they have processing power and storage that is greater than many of the computers you might have used years ago. For many people, they’ve also replaced the desktop computer and other devices they may have had in the past.

Because mobile devices have an operating system, applications, and Internet connectivity, they also have vulnerabilities to threats previously associated with a home PC. This includes virus and malware infections, hacking, privacy issues, and other potential threats discussed throughout this book. If you haven’t already configured your mobile device to be more secure, you should do so as we go from chapter-to-chapter.

Mobile apps

Mobile apps are applications that are developed to run on a mobile device. They are often lightweight versions of software created for your home PC, and may be created to perform a single function or a group of related functions. Others are designed with mobility in mind, or exclusively for certain devices.

When you first install an app, you’re provided with a screen that tells you what permissions the app is requesting. This may include access to shared files, being able to view your location, being able to read your phone state, and so on. For the application to work, it may need some very deep permission, but you should always review and question what it wants.

First, look at what the app is for, and what you expect it to do. If you downloaded a weather app, it might have a need to access your current, network-based location. After all, it would need to know your current location to tell you what the weather in my area will be like. However, if it’s asking for access to shared files, you’d rightly wonder why it would ever need that.

You should also be concerned when an app combines permissions. For example, if you had a free app, it might ask for permission to the Internet so it could display the advertising that funds its development. If the app also asked permission to access the contents of your SD card, you should be concerned. The app would be able to post data from your device (including any photos you have on a phone or tablet) to the Internet.

Certain apps may also want to access your online accounts. For apps provided by Facebook, Twitter, or other social media sites, this is required for basic functionality, so you can post or tweet. As we’ll see in Chapter 6, Protecting yourself on social media, there are settings related to your security and privacy that you can configure while using such apps. However, if an app hasn’t been developed by the site you’re using, you should question whether to install it. Just like anything, you can always read online reviews about the app, and decide if it’s okay to use.

In many cases, you can adjust permissions prior to installing, but for some it’s a take-it-or-leave-it situation, and you’re left with the choice of not installing it or trusting that it’s okay. Once an app is installed, you can view it’s permissions through the App Manager on your phone or tablet, and adjust the permissions from there. If you do deny an app the permissions it requests or needs, it may not function as expected.

Information shared and collected by apps

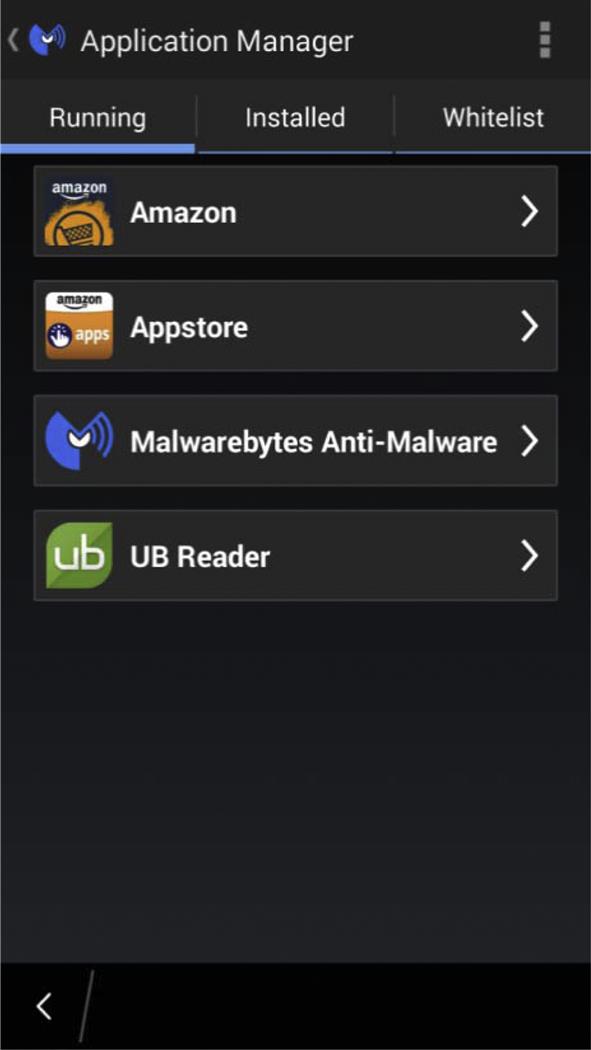

One way to view the permissions and privacy of apps installed on your phone is by installing Malwarebytes Anti-Malware Mobile. While we’ll discuss the primary purpose of this app (scanning for malware) in Chapter 3, Software problems and solutions, as seen in Fig. 1.3, it also provides an App Manager to view the apps that are running and installed. By clicking in an app on the list, you can close it, view details about it, clear its cache, and view its permissions. If the app is locked up, you can force it to stop, and if it’s problematic or no longer needed you can uninstall it.

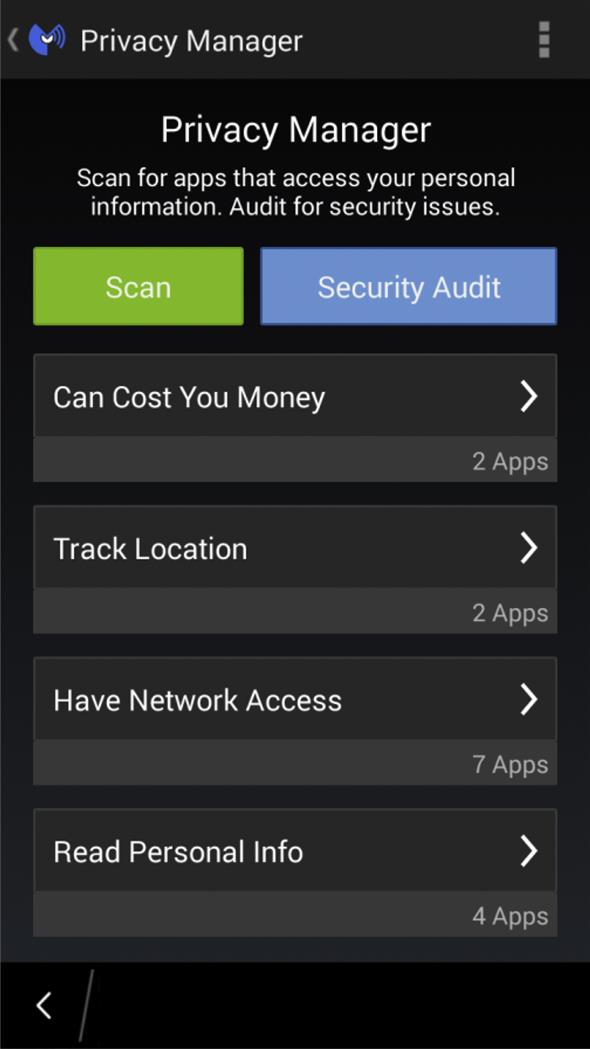

The mobile version of Malwarebytes Anti-Malware also includes a Privacy Manager. As seen in Fig. 1.4, you can scan the device to see a list of apps that can cost you money, track your location, has network access (i.e., can connect to the Internet), reads personal information, accesses settings, monitors calls, and other areas of concern. You can also click on the Security Audit button to see a list of recommended actions to make your device more secure.

Location feature

Many apps use a location feature that can track where your phone or tablet (and presumably you) are. The feature is useful if you’re using GPS software on the device, or other apps that use location-specific information. For example, perhaps you have an app that provides coupons, alerts you on sales, or some other function that needs to know what stores are nearby. If you use such apps, you should leave the location feature on your device turned on, and then review what other apps have permission to see your location. If you don’t use any apps that require permission to see your location, then turn it off. To turn off locations services:

![]() On an Android, tap Settings, tap More, and then slide the Location slider to Off.

On an Android, tap Settings, tap More, and then slide the Location slider to Off.

![]() On an iPhone, tap Settings, tap Privacy, tap Location Services, and then slide the Location Services slider to Off.

On an iPhone, tap Settings, tap Privacy, tap Location Services, and then slide the Location Services slider to Off.

![]() On a Blackberry, tap Settings, tap Location Services, and then slide the Location Services slider to Off.

On a Blackberry, tap Settings, tap Location Services, and then slide the Location Services slider to Off.

Smart TVs and Game Systems

Internet access has extended from computers and mobile devices to other types of systems. Smart TVs are televisions that have integrated features to connect to the Internet, allowing you to surf the Web, stream video, and install various apps. Even if your TV doesn’t have these features natively, you may have similar functionality through game systems like Sony PlayStation, Microsoft Xbox, and Nintento Wii. Because the devices are exposed to the Internet, and have the functionality to browse sites, install software, and perform different functions through various apps, you should be concerned about how vulnerable these devices are, how they’re used, and the privacy of information exposed through them.

You should regularly check your system settings, and use any update features to ensure the firmware is up to date. Firmware is a program or set of instructions that’s been programmed on to a piece of hardware. The system may also provide notifications instructing you to update it. Any apps and games that you’ve installed may also check to see if new versions are available. For example, if Netflix is installed, you’ll be notified when you open it that you need to upgrade to a new version, and be forced to install it. This fixes any security problems, and may provide new features that weren’t previously available.

Internet of Things

The Internet of Things refers to devices that have the ability to connect to the Internet or local Wi-Fi networks. To do this, the device is assigned an IP address, uniquely identifying it on a network. A washer and dryer might have features that allow it to connect to Wi-Fi to send a message to smartphone apps, allowing you to monitor wash cycles and status. Similarly, a refrigerator might have a panel similar to a tablet on the door, which can be used to keep an inventory of food, and how long it’s been there. In addition, there are heart monitors that can connect to a medical specialist’s computer, transponders to keep track of livestock, and other devices that use the Internet to communicate and acquire updates.

It’s important that you’re aware of the devices you own, who supports them, and whether you’re responsible for any updates. In the case of a heart monitor, you would obviously leave any maintenance to a specialist, but there may be some you’re responsible for. If we were to look at the washer/dryer that connects to the Web to tell an app on your phone about its status or if there’s a problem, you would need to update the app when new versions are out. Because there probably isn’t antivirus software or other programs available to protect your device, you’ll want to ensure your home network itself is secure (as we discuss in Chapter 2, Before connecting to the Internet).

Using Different Windows Accounts

Have you ever considered setting up a single Facebook account for your entire family and allow guests to use it when they visit your house? Of course not, and most people would (rightly so) be shocked at the suggestion. Guests and family members could change settings, compromise your security and privacy, and cause all sorts of problems. As absurd as a shared account sounds, many fail to apply the same logic to accounts on a home computer.

It’s common to see home PCs setup so that everyone logs in using the same account, allowing everyone access to files and settings on the computer. It’s even worse when it’s an administrator account and has full control over the machine. User accounts separate people using the computer into different profiles, allowing them to choose different backgrounds, screensavers, locations to store photos and other files, and have different settings applied to each person. They may also be necessary if you’ll be using some of the tools we’ll discuss in this book, such as when you want to monitor or apply parental controls to a kid’s account.

While you can create multiple user accounts in Windows, the account has to be set as a certain type, which determines the level of control they have over a PC. These are:

![]() Standard account, which provides access but doesn’t allow the person to make changes that will affect other users. Almost all of your accounts should be a standard account.

Standard account, which provides access but doesn’t allow the person to make changes that will affect other users. Almost all of your accounts should be a standard account.

![]() Administrator, which has full control and can install software, create and delete accounts, and make changes to settings that affect everyone. You should only have one administrator account on a machine, and this should only be logged onto when you need to make changes. You shouldn’t name any account of this type “Administrator” or “admin” as hackers know these are commonly used. Instead, give the account a different name that doesn’t indicate its purpose.

Administrator, which has full control and can install software, create and delete accounts, and make changes to settings that affect everyone. You should only have one administrator account on a machine, and this should only be logged onto when you need to make changes. You shouldn’t name any account of this type “Administrator” or “admin” as hackers know these are commonly used. Instead, give the account a different name that doesn’t indicate its purpose.

![]() Guest, which should only be used when people need temporary access. It’s advisable that you disable any accounts on the machine named “Guest,” as it’s a common account name. Instead, if you want to provide guest access, create a new account with a different name.

Guest, which should only be used when people need temporary access. It’s advisable that you disable any accounts on the machine named “Guest,” as it’s a common account name. Instead, if you want to provide guest access, create a new account with a different name.

As we’ll see in Chapter 10, Protecting your kids, there are also child accounts that you can setup in Windows, which work with parental control features. When a child account is setup on machines using Microsoft Family Safety, you can set time limits that control when and how long a person can use the computer, what kinds of games they can play, allow or block specific programs on the computer, and other settings to protect a child.

The steps involved in creating and managing a user account vary between versions of Windows. If you’re using Windows 7, you would do the following:

1. Click on the Start button and click Control Panel in Windows 7.

2. Under User Accounts and Family Safety, click User Accounts, and then click Manage another account.

3. Click Create a new account.

4. Enter the name you want to give the account, which could be the name of the person using it, and select the type of account. In most cases, you’ll want to create the account as a Standard user.

6. When you’ve returned to the Manage Accounts screen, the new account will appear in the list of existing accounts. By clicking on the account, you can then manage the account, and create a password, change the account type or delete the account.

Setting up a user account in Windows 8x and 10 is a little different, and you’ll notice that they try to steer you into creating an online account. It will try to set you up with a Microsoft account, which you would use to logon and use Microsoft services. It also allows you to sync your settings, so that any computer you use will have your profile picture, apps, and other settings when you logon. Despite this, you can still setup a local user account on your PC. To setup a local user account, you would do the following:

1. In Windows 10, click on the Start menu, click Settings, and then click Accounts. In Windows 8x, click Settings, and then click Change PC Settings.

3. In Windows 8x, click Other accounts. In Windows 10, click Other user accounts.

4. Click Add an account, and then click Sign in without a Microsoft account.

6. Enter the username for the account. For simplicity, this can be the name of the person who will use the account.

7. Enter a password, and then reenter it to confirm it. In the Password hint box, you can optionally give a hint that will help the person remember their password. When entering a hint, don’t reenter the password, or give such an easy hint that anyone reading it will be able to guess the password. Click Next, and then click Finish.

8. Once finished, you’ll see the new account in the listing. By clicking on it, you can then manage the account, and change the password, account type, and modify other aspects of the account.

Biometrics

As we discuss in Chapter 2, Before connecting to the Internet, any password you create should be a strong one that’s difficult to guess, and will be harder for password cracking software to break. However, passwords aren’t the only way to login to a system. You can also use biometrics.

Biometrics is the process of identifying who you are based on certain characteristics. By looking at unique features like fingerprints, facial features, and so on, a system is able to identify who you are and provide access. If you have a child who may find it difficult remembering a password, or want to save time typing out lengthy passwords, biometrics provides a good solution to securing a system.

A number of operating systems support biometrics. Apple uses fingerprint scanning in iOS devices, while Android supports facial recognition and finger drawn patterns. Windows also supports the ability to logon to the operating system using fingerprint, iris, and facial recognition.

Fingerprint readers prove your identity by scanning an image of your fingerprint, and saving a copy of it to the system. When logging into Windows or a website, you would press your finger on the reader, and it would compare it to the fingerprint on file. There are a number of laptops that come with a built-in fingerprint reader, but you can purchase them separately and install them on your computer.

Windows 10 also provides built-in biometric login features, called Windows Hello. With this feature, you can use face, fingerprint, or iris recognition to logon. Facial recognition involves the system recognizing your face by reading characteristics, such as the distance between your eyes, ears, and so on. Iris recognition involves the system looking at the pattern in one or both of the irises in your eye. When you sit in front of the camera on your computer, the characteristics of your face or eye are compared to what’s on file. If it’s a match, you’re logged in.

To use these features in Windows 10, you would click Start, click Accounts, and then click Sign-in options. Once on this screen, you’ll see several options for setting up face, fingerprint, or iris. However, you’ll only be able to use these if your computer has a fingerprint reader or camera that supports it.

Physical Security

When people think of protecting computers, so much is said about software and settings that it’s easy to forget someone might easily walk off with a device. Laptop computers, tablets, smartphones, monitors, printers, and even desktop computers are smaller and lighter than ever before, making them easy to steal. This is especially true in public or semipublic areas that can’t be or haven’t been secured, and situations where your device is unattended.

Thefts are often crimes of opportunity. Generally, a burglar or thief won’t target a person. They don’t care about you, only that you’ve made it easier to get what they want. For example, every year police will get calls from people who were outside, left their door unlocked, and later found they were burgled. The thief simply went door-to-door, checking until they found an unlocked house. While you’re gardening at the side of the house or mowing the backyard, someone walked out the front door with your laptop, phone, wallet, and other possessions. The lesson here is to make your belongings secure, so it isn’t worth the thief’s trouble and he or she will move on to another potential target.

While a lock may not seem like much of a deterrent, it’s often enough. Laptops and other small devices are often stolen from offices while their owners have taken a quick break or gone to a meeting. Students in dorms may also find things stolen by someone who simply walked in and took it. Keep any USB sticks, music players, or small devices in locked desks, and keep the room, apartment, and house locked so that no one can enter while you’re not there.

The usefulness of many modern devices is that they’re portable, allowing you to take them with you to class, work, shopping, or any other place you’re heading. It also expands the area where they can be stolen. You should never leave devices unattended. Leaving your wallet and tablet in an open purse, setting your phone on a store counter, or walking away from a laptop in a lecture hall presents a tempting target to thieves.

Another place where these devices are often left unattended is in cars. You might think you’re your laptop bag or phone is safe on the backseat, but it’s visible to anyone walking by. Someone with a slim jim or coat hanger could unlock the car, one of several doors may be unlocked, or smashing the window would allow them to get it. You might think leaving your belongings in the trunk is an option, but this causes another problem: temperature. Laptops, phones, and other devices are susceptible to heat and cold. Leaving your device inside an idle car or trunk means that it can get extremely hot or cold, damaging the device to the point it’s irreparable. The same applies to any source of heat or cold that has direct or close proximity to the device.

Impact damage is another common cause of devices being broken. When traveling, keep them on your person or as carry-on luggage. You also should avoid setting them down on the floor, such as when you’re waiting in a walkway or lecture hall and decide to set a laptop bag on the floor. Not only can someone easily pick it up and walk away, someone may accidentally kick or step on it. Similarly, avoid setting your devices on any vibrating surfaces, such as machines in a factory setting, as the shaking can jostle connections loose or cause other damage. To avoid damage from impacts and vibration while traveling from place-to-place, use a bag or case that’s padded and designed to protect laptops, tablets, or other devices.

Locking Down Hardware

There are a number of ways to prevent hardware from being lost or stolen. Starting at the smallest device, USB sticks or thumb drives are able to store an incredible amount of data, but are small enough to misplace or be taken without noticing right away. If you can’t keep them in a locked drawer while not being used, you should have them on your person. Attaching them to your keychain on a lanyard makes them portable and hard to lose. It will be easier to notice it’s missing if you leave the USB stick in a computer once you’re done.

Many laptops, desktop computers, and larger external storage devices like removable hard drives and CDDVD drives have built-in slots that are designed to connect with a cable lock. The cable connects to the devices, locks in place, and the other end can be attached to something stable and difficult to move. If the steel cable is attached to a desk leg or an anchor that’s affixed to a wall, it makes it almost impossible to steal the device without doing damage or being noticed. The way you release your device is with a key or combination. If you’re thinking this might be an expensive way of securing a device, think again. Cable locks are available online and at computer stores for around $30.

Summary

In this chapter we introduced you to some basic elements of cyber safety, and also showed you some of the potential threats you might face in protecting yourself and your devices. We saw how important it is to keep private information private, and showed you some ways to review settings and secure your computer and mobile devices. Now that we’ve touched on some basics, let’s move on to Chapter 2, Before connecting to the Internet, and discuss some of the steps to take before connecting to the Internet.