CHAPTER 5

Empowered Customers (Buyers)

Walmart knows its customers. Store greeters welcome shoppers when they arrive and smile goodbye when they leave. Walmart’s folksy charm is just one component of the company’s laser focus on delighting its customers. Walmart intensely tracks customer purchases and behaviors, as does its only true rival Amazon. This data-driven awareness leads to new insights and business ideas that delight customers.

For example, Walmart noticed its customers were spending less per store visit. After intense research, the company discovered why. Its customers were allocating more discretionary income to healthcare, so they had less to spend on other things. In December 2018, the Commonwealth Fund issued a white paper titled “The Cost of Employer Insurance Is a Growing Burden for Middle-Income Families.”1 It reports that the percentage of median income consumed by employee health insurance premiums and potential deductible spending rose from 7.8 percent in 2007 to 11.7 percent in 2017. The burden is highest in Louisiana and Mississippi, where these healthcare costs consume more than 15 percent of median income.

Rather than fight the trend, Walmart is finding ways to help both these customers and its own employees get more value from their healthcare purchases. It turns out that what’s good for Walmart customers and employees is also good for Walmart itself.

Walmart executive Lori Flees explained the company’s logic at a Minneapolis conference in October 2018.2 Walmart is the nation’s largest employer. Providing health insurance for Walmart’s 2.2 million workers is the company’s second-highest cost (after wages). Rather than complain, Walmart decided to become a better purchaser of healthcare services and work with health companies that deliver better outcomes at lower prices. This value-first mindset is transforming American healthcare. As Flees summarized,

So these are the things that drive us to be interested in health care: Our customers need help. Our associates need and want to be healthy. And it’s good for our business.3

Like growing numbers of Americans, Walmart’s customers don’t just worry about health, they also worry about accessing and paying for healthcare services. Walmart’s motto, “Save Money. Live Better,” guides the company’s strategic thinking and market positioning. Renowned for finding affordable solutions to customer challenges (e.g., access to affordable banking services), Walmart sees opportunity in healthcare.

Toward that end, Walmart pursues innovative strategies that improve health and reduce healthcare costs for employees and customers. It contracts directly for specialty care procedures at fixed prices (through full-risk “bundled” payments) for the entire episode of care. For example, Walmart has signed agreements with designated “centers of excellence” for lower-cost, higher-quality spinal surgery, while slashing payments for similar procedures with other providers. Most spinal surgery is unnecessary, so Walmart incentivizes its associates to explore noninvasive treatments for their back pain before going under the knife.4 Ironically, physicians at Walmart’s orthopedic centers of excellence disproportionately recommend noninvasive procedures. Too bad the local providers didn’t do that in the first place.

To promote wellness, Walmart markets “Great for You” healthier foods to its customers. It also operates in-store clinics, pharmacies, and vision centers to improve access to those services. It even hosts in-store health screening events to catch “patients” while they go about their normal lives. Since 2006, the retail giant has sold $4 generic prescriptions and has partnered with Humana to offer lower-cost drugs to Medicare patients.

The bottom line is that Walmart wants to bring “everyday low prices” to healthcare. It’s not alone—so do Amazon, CVS, Walgreens,5 and even Best Buy.6 Imagine that, big retailers see opportunity in providing value-added healthcare to customers.

Incumbents should beware. Healthcare is under siege. Big retailers are attacking the System’s soft underbelly and winning market share by delighting customers. It turns out that retailers know a thing or two about understanding and fulfilling customer needs.

MEETING CUSTOMERS’ JOBS-TO-BE-DONE

Management guru Peter Drucker distilled the essence of businesses as follows, “The purpose of a business is to create and keep customers.” This simple statement has profound implications for healthcare as it moves into a pro-market, consumer-focused era. It serves as an orienting principle for identifying customers’ jobs-to-be-done (“Jobs”),7 designing service offerings, and building business models. The best companies relentlessly focus on solving customer needs, wants, and desires. This is the power of demand-driven change. It delivers revolutionary outcomes to consumers. Just consider how customer-centric Walmart is.

The flip side of this equation is that customers must have the knowledge, inclination, and wherewithal to select the products and services that fulfill their “Jobs.” When they do, customers engage with companies that solve their problems and disengage from those that don’t. As customers increasingly exert their purchasing power in healthcare, they will transform the industry’s supply-demand relationships. This emerging market dynamic is the foundation for the customer revolution in healthcare.

Fulfilling customers’ “Jobs” is no small challenge for health companies. In Chapter 3, I observed that healthcare principals routinely execute transactions without customers. Instead, they strive to increase revenues and profits by optimizing service volume and payment formularies. Quality, outcomes, and great customer service (i.e., value) are not prerequisites for success in fee-for-service medicine. This payment reality and the managerial orientation supporting it block health companies from reading the market signals customers send through their purchasing decisions. Customer-centric businesses rely upon these market signals to adjust prices, services, and product quality to optimize sales and profits.

Peter Drucker also noted, “If you [health companies] want to do something new [solve customers’ “Jobs”], you have to stop doing something old [clinging to FFS business models].”

Part III, “Revolutionary Healthcare,” will dissect the many “somethings new” that health companies are doing to succeed in the post-transformation marketplace. The essential message here is that empowered buyers are the “revolutionary force” driving the industry into “Revolutionary Healthcare.” Health companies that fail to understand this emerging reality and adjust their business models accordingly will lose market relevance.

Interestingly, Walmart is both a customer and a competitor to health companies. There are two basic types of business models with two categories of customers:

• Business-to-business (B2B)

• Business-to-consumer (B2C)

As a self-insured company for its employees’ health expenditures, Walmart is a major purchaser of healthcare products and services (a customer). Its decision to contract directly with select health companies for care services makes it a sophisticated B2B customer.

When fulfilling customers’ jobs-to-be-done, it’s essential to understand what “Job” the customer is hiring the company to do. In direct contracting for its employees’ healthcare, Walmart’s “Job” is finding affordable, high-quality healthcare service providers to deliver appropriate care to employees. Health companies that want to attract Walmart and like-minded companies will organize their business models to solve this “Job.”

Walmart also competes with health companies, particularly in B2C products and services. Already a major pharmacy, Walmart now offers clinic services, wellness education, eyeglasses, and healthy food. Expect it to expand the range and scale of its health and healthcare offerings. It understands its customers’ healthcare “Jobs.” Its trusted brand with price-conscious consumers positions it well for a disrupting healthcare marketplace where consumers seek affordable solutions to routine health and healthcare problems.

Health companies that want to compete in the B2C healthcare marketplace will likewise need to develop business models that solve consumers’ healthcare “Jobs.” In doing so, they will encounter formidable competition from retail companies like Walmart that have well-developed consumerism experience and instincts.

As B2B and B2C channels mature in healthcare, customers will search for and discover better ways to solve their healthcare “Jobs.” They will redefine and transform the healthcare industry through their purchasing decisions. This type of demand-driven change is well known outside healthcare, but alien to incumbent health companies.

What distinguishes this demand-driven period of market reform from other attempts to reform the System is that the buyers of health and healthcare services (customers) now have ways to pay for health and healthcare services that align with their “Jobs.” Full-risk contracting for healthcare services shifts the power dynamic from healthcare service providers to healthcare service purchasers. It is the unstoppable force that pushes Revolutionary Healthcare forward.

FULL-RISK CONTRACTING: THE TRANSFORMATIVE CATALYST

Although forms of full-risk contracting have existed for decades, they are now gaining sufficient critical mass in select markets to change payer and provider business models. Before digging into that trend and its implication, let’s first examine the current distribution of payers and payment vehicles.

There are three categories of healthcare purchasers who either pay for healthcare directly (through self-insurance mechanisms) or buy health insurance to cover that risk. I list them below with the 2017 figures for the percentages covered within each category:8

• Employers (companies)—49 percent of Americans

• Governments (federal, state, and local)—36 percent of Americans

• Individuals (insured and uninsured)—16 percent of Americans

Employer-sponsored health insurance programs cover roughly half of all Americans. Governments purchase healthcare through Medicare, Medicaid, government agencies, and employee insurance programs. Individuals who pay for their own healthcare either directly or through a state exchange are far fewer in number. Nine percent of Americans do not have any health insurance coverage.

Healthcare coverage and healthcare expenditure are not correlated. Even though half of Americans have private health insurance and they pay disproportionately more for individual healthcare transactions, private insurance accounts for only 34 percent of total health expenditure (2017 figures). Public insurance (Medicare, Medicaid, Veterans Administration, Defense Department, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program or CHIP) account for 41 percent of total expenditure. The conclusion is obvious. Publicly insured individuals disproportionately consume healthcare services, but governmental payers pay less (often substantially less) per transaction. “Out-of-pocket” expenditures account for 10.5 percent of healthcare expenditure.9

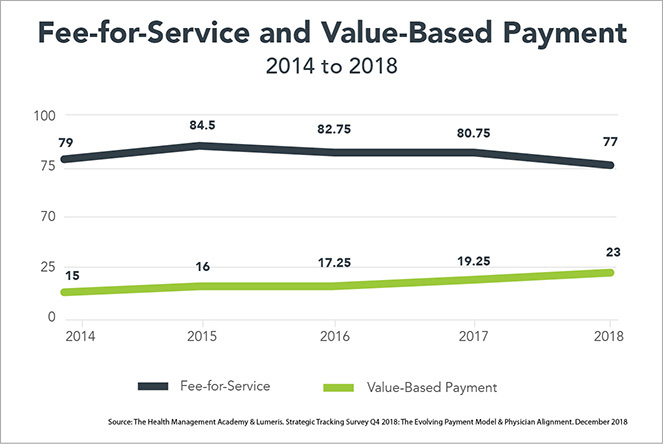

As discussed in Chapter 2, complex fee-for-service payment formularies dominate healthcare transactions. Figure 5.1 details the FFS and value-based payments received by large health systems. FFS payment remained above 80 percent of total payment between 2014 and 2017 but dropped to 77 percent in 2018.

FIGURE 5.1 Hospitals are still living in a fee-for-service world.

Although the 2018 decrease in FFS payments is laudable, the vast majority of value-based payments are in shared savings contracts with no downside risk. That is, providers are not at risk if they do not achieve the targeted savings level. A simple example will illustrate.

A hospital contracts with an insurance company to conduct knee replacement surgery. Historically, the insurance company has paid the hospital $25,000 for this surgery. In a shared savings agreement, the hospital and insurance company agree to equally split any savings below the historic $25,000 payment level. There is no penalty to the hospital if it does not achieve any savings (hence, no downside risk).

These upside-only payment arrangements are an intermediate step toward true value-based payment and delivery. US healthcare will not achieve true value-based healthcare until health companies accept full risk (upside and downside) for delivering targeted high-quality outcomes with great customer experience.

In full-risk contracting, health insurance companies pay a fixed amount to providers for procedures, say $20,000 for knee replacement surgeries. Providers profit if they perform the surgery at a cost below $20,000 while meeting quality and service standards. However, providers lose money if their costs to perform the surgery exceed $20,000 and/or they fail to meet quality and service standards.

Full-risk contracting achieves radical payment reform by making health companies fully accountable for care outcomes, quality, and costs. It comes in two basic forms:

• Predetermined “bundled” payments for episodic care like the knee replacement surgery described above. Under bundled payment contracts, providers receive a predetermined payment to cover the total treatment cost for a specific episode of care (from admission through treatment, discharge, and recovery) over a defined period. Bundled payment procedures must meet predetermined quality measures to receive payment. The contracts generally carry 90-day performance guarantees.

• Fixed monthly or “capitated” payments to cover the health risk for distinct populations. These programs, such as Medicare Advantage (MA), adjust the monthly payment for each individual’s perceived health risk. Going full risk for a patient’s overall health incentivizes the provider to deliver preventive and other low-cost healthcare services that avoid costlier services later. It motivates providers to make and keep a population of consumers healthy.

In healthcare’s most overused metaphor, health companies’ leaders describe their companies as straddling between a “volume” dock and a “value” boat as the boat drifts into the lake. Leaders using this metaphor implicitly acknowledge their acceptance of suboptimal performance in exchange for FFS payment.

Fee-for-service payment is transactional and rewards activity, not outcomes. By contrast, full-risk contracting is exactly the opposite. It pays for outcomes and rewards providers that deliver them efficiently. It is almost impossible for health companies to practice activity-based FFS medicine and outcomes-based full-risk contracting simultaneously. This explains why most providers and payers do not participate in full-risk contracting or suffer significant losses when they do.

In essence, full-risk contracting shifts care-management risk from governments, employers, and individuals to payers and providers. Full-risk contracts incorporate both business-to-business and business-to-consumer customer segments. Governments and large employers can establish full-risk contracts with health plans and/or health systems. Individual plans bought on public health exchanges are full-risk contracts. In addition, health plans can enter into full-risk contracts directly with consumers through the Medicare Advantage (MA) program. Increasing numbers of states are pursuing forms of direct contracting for their Medicaid populations.

As noted at the beginning of this chapter, Walmart has negotiated full-risk bundled payment contracts for select specialty treatments with designated centers of excellence. They are not alone in pursuing full-risk contracting to improve outcomes, lower costs, and eliminate unnecessary treatments. Here are three notable examples:

• In November 2018, the Trump administration reversed course and embraced mandatory bundles for select orthopedic, cardiac, and oncology treatments. When making the announcement, Secretary Azar observed that mandatory models (full-risk bundled payments) are “the most effective way to . . . save money and improve quality.”10

• In August 2018, General Motors signed a five-year agreement with Henry Ford Health System to provide comprehensive healthcare services for GM’s salaried employees in Southeast Michigan. This is a landmark transaction that moves GM away from pure fee-for-service (FFS) payment while holding Henry Ford accountable for care delivery cost, quality, outcomes, and service levels.

The GM–Henry Ford agreement will be Michigan’s first direct-care contract. It reflects changing market dynamics and a maturing relationship between large self-insured employers and large integrated healthcare systems.11

• In March 2018, the state agency Massachusetts Medicaid (MassHealth) began contracting with 17 health systems to manage the care for 850,000 Medicaid enrollees based on predetermined monthly payments for each individual.

The program assigns members to health systems. In return, the health systems assume financial risk for all their expenditures caring for those individuals in exchange for predetermined monthly payments that are based on individual health status. The program will monitor costs, quality, outcomes, and member experience.

In announcing the program, Governor Charlie Baker stressed that the agreements with health systems “will directly lead to better and more coordinated care for MassHealth members across the Commonwealth.”12

As illustrated above, governmental and commercial payers are embracing full-risk contracting. Adam Boehler, President Trump’s director of the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) since August of 2018, proclaimed during a November 2018 interview that “one of our prime goals is to get rid of fee for service [payment].” This is a bipartisan position. Patrick Conway, Boehler’s Obama-appointed predecessor (now CEO of Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina) is equally adamant. At an October 2018 conference, Conway said, “I want fee-for-service, volume-based care to die, and I want to kill it as fast as possible.”13

Like rock and roll, full-risk contracting is here to stay. Medicare Advantage plans are just the most prominent form of full-risk contracting. Given its transformative potential, it’s time to examine Medicare Advantage more closely.

ADVANTAGE MEDICARE ADVANTAGE

The System’s unforgivable failure to coordinate care, manage chronic disease, and promote health increases human suffering and treatment costs. In stark contrast, high-performing Medicare Advantage (MA) programs accomplish these objectives through focused medical management. MA works because its payment and performance incentives reward comprehensive and holistic care delivery. Its shifts the government’s care management risk to MA health plan sponsors. In this sense, MA represents successful public-private partnerships that advance value-based reform.

Full-risk contracting arrangements, including Medicare Advantage, are the transformative force challenging conventional healthcare business models. Under full-risk contracting, payers and providers need new capabilities to improve patient-centric health outcomes. MA plans that cannot manage their members’ care within fixed revenue parameters lose money. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) provides funding within predefined parameters to MA plan sponsors.

Commercial health insurers develop, market, and administer Medicare Advantage plans that compete for members in the public marketplace. Customers select MA plans with the benefits they want at prices they’re willing to pay. Successful MA plans attract members, meet their health needs efficiently, and receive high quality scores.

Medicare Advantage is gaining sufficient critical mass in many markets to stimulate vertical integration of care payment and delivery. A third of Medicare beneficiaries are now enrolled in MA programs. That percentage could grow to as high as 50 percent by 2025 as record numbers of baby boomers age into Medicare beginning in 2019. Properly executed, MA has the scale to transform US healthcare delivery by aligning payment incentives with desired health outcome objectives. A recent study by Avalere found compelling evidence that MA plans manage the health of sicker Medicare beneficiaries more cost effectively than traditional FFS Medicare. Key findings from the Avalere study include the following (as a reminder, FFS = fee-for-service):

• Medicare Advantage had a higher percentage of beneficiaries with chronic conditions who enrolled in Medicare due to disability (36 percent versus 22 percent FFS) and who are dual-eligible/low-income beneficiaries (23 percent versus 20 percent FFS) than FFS Medicare.

• Medicare Advantage beneficiaries, compared to FFS Medicare beneficiaries, had a 57 percent higher rate of serious mental illness (9 percent versus 5 percent of FFS) and a 16 percent higher rate of alcohol/drug/substance abuse (7 percent versus 6 percent of FFS).

• Utilization of costly healthcare services was lower for Medicare Advantage beneficiaries, including 23 percent fewer inpatient stays (249 versus 324 per 1,000 beneficiaries in FFS Medicare) and 33 percent fewer emergency room visits (511 versus 759 per 1,000 beneficiaries in FFS).

• Average annual Medicare Advantage beneficiary costs were not significantly different from average costs for FFS Medicare beneficiaries, but annual spending per beneficiary on preventive services and tests was 21 percent higher in Medicare Advantage ($3,811 versus $3,139 in FFS Medicare); FFS Medicare had 17 percent higher spending on inpatient costs ($3,477 versus $2,898 in Medicare Advantage); and FFS Medicare had 5 percent higher spending on outpatient/emergent care services ($2,474 versus $2,359 in Medicare Advantage).

• Medicare Advantage outperformed FFS Medicare on several key quality measures, including a nearly 29 percent lower rate of all potentially avoidable hospitalizations (17 percent versus 24 percent in FFS); 41 percent fewer avoidable acute hospitalizations; 18 percent fewer avoidable chronic hospitalizations; and higher rates of preventive screenings/tests, including LDL testing (5 percent more) and breast cancer screenings (13 percent more).

• Relative to FFS Medicare, Medicare Advantage beneficiaries in the clinically complex diabetes cohort experienced a 52 percent lower rate of any complication (8 percent versus 17 percent of FFS and a 73 percent lower rate of serious complications (2 percent versus 6 percent of FFS).14

By any measure, these are impressive results. The Avalere study summarizes the results of its analysis as follows:

These results indicate that, compared to FFS Medicare, Medicare Advantage provides more preventive services and utilizes interventions designed to better manage chronic conditions, which may avert preventable complications and result in lower overall costs. This was especially true among the most clinically complex and dual-eligible/low-income beneficiaries.

Despite Medicare Advantage beneficiaries having more social and clinical risk factors, they had similar costs to those in FFS Medicare overall, indicating that Medicare Advantage’s focus on coordination of care may lead to more efficient treatment patterns and care delivery. Medicare Advantage has inherent incentives to coordinate care and deliver preventive services that do not exist in the FFS Medicare program.

The study findings show that Medicare Advantage beneficiaries with chronic conditions experience better outcomes, fewer adverse events at similar or lower costs, and suggests a better quality of life for beneficiaries with chronic conditions in Medicare Advantage.

The marketplace sees enormous investment potential in Medicare Advantage companies. In October 2018, Devoted Health raised $300 million in private equity financing led by Andreesen Horowitz with a company valuation of $1.8 billion.15 Founded in 2017 by health tech entrepreneurs Ed and Todd Park, Devoted is a nationwide Medicare Advantage company offering customer-focused, relationship-based, easy-to-use health plans that deliver the right care at the right time.

Addressing Medicare Advantage’s Structural Flaws

Medicare Advantage plans require two core competencies to succeed financially. The first is the medical management of the plan’s enrollees. As described in the Avalere study, everything good in MA results from the active management of MA plan enrollees. Enhancing MA plans’ collective ability to manage members’ health is America’s last, best hope for transforming healthcare delivery.

The second core competency is managing revenue flows in and out of the health insurance plan. Everything bad in Medicare Advantage results from the design and application of CMS payments to MA health plans. “Fixing” these flaws would dramatically improve MA’s performance and speed health system transformation.

The following four structural flaws distort the proper functioning of MA plans.

1. Risk adjustment

2. Baseline variation in FFS payment rates

3. Contracting friction between MA plans and providers

4. Release mechanism for high-cost enrollees

Let’s address them individually.

1: Risk Adjustment

Risk adjustment is the mechanism through which CMS calibrates the payments it makes to Medicare Advantage plans for the expected care cost of MA plan enrollees. CMS employs a complex formulary employing demographic and diagnostic information for each beneficiary. Sicker enrollees generate higher monthly payments for MA plans.

The marketplace is always smarter than central planners. MA plans have become adept at identifying additional diagnoses that increase monthly premiums separate and apart from the enrollee’s true health status. For this reason, risk scores are 8 percent higher and have risen 1.5 percent faster for MA enrollees than for traditional Medicare enrollees.16

Higher payments for specific beneficiaries inflate MA plan revenues and profits. In a February 2017 Health Affairs article, Richard Kronick projects this “coding intensity” could increase MA spending by more than $200 billion over 10 years.17

CMS could eliminate much of this “diagnosis gaming” by assuming the demographic and diagnostic characteristics of MA and traditional Medicare populations are equivalent. Even better, CMS could move away from risk adjustment altogether and apply experience ratings to specific MA populations. Experience ratings assign premiums based on the actual healthcare use of similar populations. The larger the populations, the more accurate the assessments.

2: Baseline Variation in FFS Payment Rates

The complexity of Medicare’s payment formularies makes them vulnerable to manipulation and results in remarkable payment variation across the nation. For example, the 2016 per capita cost in Miami/Dade County was $14,133. That figure was 76 percent higher than the 2016 per capita cost of $8,054 for Seattle/King County.18

Physician practice patterns are the primary factor driving fee-for-service payment differentials exhibited in Miami and Seattle. Medicare patients get more care in Miami (much of it unnecessary) than in Seattle. These payment differentials exist despite Seattle’s higher cost of living.19

No good deed goes unpunished. It’s unfair that more efficient healthcare markets like Seattle receive lower per capita payments for generating the same or better care outcomes. Lower payment levels also make it harder for Seattle-based MA plans to generate profits by eliminating unnecessary healthcare expenditures. It’s a lose-lose proposition.

Medicare should decouple Medicare Advantage plan per capita payments from fee-for-service-driven payment formularies and replace them with national, experienced-based rates. Over time, this would shift payments from higher-premium markets to lower-premium markets and result in more effective and efficient care delivery across MA plans throughout the country.

3: Friction Between MA Plans and Providers

Medicare Advantage plan ownership is highly concentrated among three commercial insurance companies. UnitedHealthcare, Humana, and Blue Cross affiliates accounted for 57 percent of nationwide MA enrollment in 2017. Eight companies and affiliates accounted for 77 percent of enrollment.20

Commercial MA plans typically contract with providers on an FFS basis for specific treatments. The plans manage their members’ care efficiently to generate higher profits. Better care management keeps medical expenditures low.

This payment model can become problematic when dominant MA plans exert price-setting pressure on providers. More commercial insurers offering MA plans levels competition within markets and establishes more balance in payer-provider price negotiations.

MA plans that contract with providers using sub-capitated rates for specific services (e.g., behavioral health services) align payment with desired outcomes in the same way capitated MA rates do for MA plans overall. More sub-capitated arrangements will improve plan performance by focusing those providers on value creation.

Concern with fair provider payment will grow as MA plans increase enrollment. Unfair payer or provider pricing power distorts market function and destroys value creation. The best way to address unfair payments by MA plans is to create more competitive MA marketplaces for both payers and providers. This will enable value-oriented health companies to differentiate, win customers, and gain market relevance for the right reasons.

4: Release Mechanism for High-Cost Enrollees

Medicare Advantage enrollees have the right to convert back to traditional Medicare at any time. This creates an incentive for MA plans to shift the financial risk of caring for their highest-cost enrollees by nudging them to convert their health insurance back to traditional Medicare. Typically, these high-cost enrollees require significant acute-care interventions.

The colloquial term for this cruel practice is “lemon dropping,” equating sick elderly members with broken-down cars. In May 2017, Tampa-based Freedom Health settled a false claims lawsuit, which included allegations of lemon dropping, with the Justice Department for $31.7 million without accepting liability.21 I have found no study that documents the scope and scale of this cost shift from Medicare Advantage plans to traditional Medicare, but the potential for abuse is enormous. The existence of this “release mechanism” creates a perverse incentive to place the company’s financial well-being above that of chronically sick enrollees. Given MA’s organic growth, eliminating this ability of MA programs to shift financial risk constitutes prudent regulatory policy.

MA’s Bottom Line

At issue is whether Medicare Advantage will be the driving catalyst for industry transformation. To realize this potential, MA must amplify its medical management capacity and diminish the financial maneuvering that compromises its effectiveness.

The future of US healthcare and the health of the US economy hang in the balance. Former president Ronald Reagan famously quoted the Russian proverb “Trust but verify” in describing his approach to negotiating nuclear disarmament with his Soviet counterparts. Employing President Reagan’s sensibility, CMS must enhance MA’s regulatory framework, trust the marketplace will evolve toward efficiency, and verify that MA plans deliver value for customers. In that way, Medicare Advantage will truly provide advantage to the American people.

FULL-RISK CONTRACTING: GAINING MARKET TRACTION

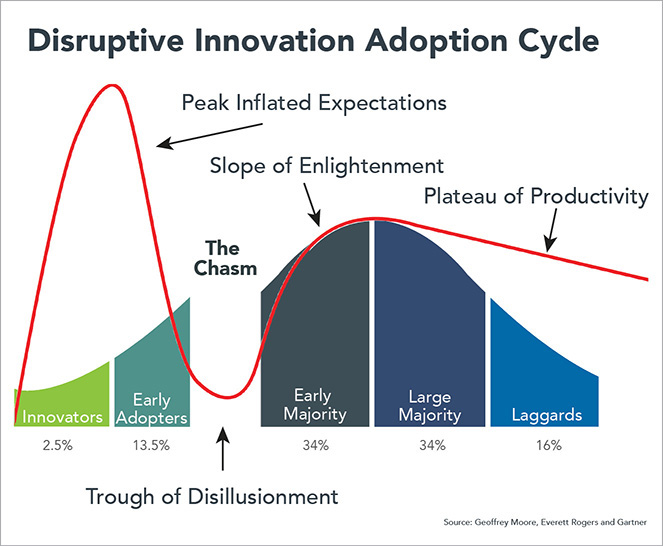

Transformative innovations, like full-risk contracting, take time to scale and advance into the marketplace. In his pioneering book Crossing the Chasm, Geoffrey Moore describes the sequencing of the following five customer groups adopting transformative innovation as it moves into the marketplace.

1. Innovators—first 2.5 percent of the market

2. Early adopters—next 13.5 percent

3. Early majority—next 34 percent

4. Late majority—next 34 percent

5. Laggards—final 16 percent

Moore identifies an adoption “chasm” between “visionaries” (innovators and early adopters) and “pragmatists” (early majority). These chasms emerge because visionaries and pragmatists have different purchasing motivations.

Visionaries want to lead innovative change and willingly take more risk. By contrast, pragmatists don’t become buyers until they believe a transformative innovation is taking hold. That occurs when the transformative innovation captures 15–20 percent market share. Only then will pragmatists move to incorporate the transformative innovation into their business models.

The technology firm Gartner developed the “hype cycle” to describe the emotional roller coaster that accompanies transformative technologies as they move through the different buyer groups. The hype cycle rises quickly to “the peak of expectation” before falling dramatically into the “trough of disillusionment” as the innovation seeks to cross the adoption chasm (Figure 5.2).

FIGURE 5.2 Adoption of transformative technologies often fails before hitting 20 percent market share because they cannot attract “pragmatic” early majority buyers.

As market share approaches and surpasses 20 percent, the transformative innovation enters “the slope of enlightenment” where pragmatists become active buyers. It settles into “the plateau of productivity” as the innovation earns widespread adoption. Many, perhaps most, transformative innovations do not develop enough momentum to cross the adoption chasm. They die in the “trough of disillusionment.” That will not happen with full-risk contracting. It will “jump the adoption chasm,” but do so unevenly. Local healthcare markets in the United States have distinctive supply-demand relationships that influence medical practice and business model configurations. Those factors will shape the pace at which individual markets shift to value-based payment.

As mentioned earlier in this chapter, the 2016 per capita total healthcare cost in Miami/Dade County was 76 percent higher than that in Seattle/King County.22 Physicians in Miami provide more care (much of it unnecessary) to Medicare patients than physicians in Seattle. These types of payment and practice variation determine an individual market’s readiness for shifting to value-based payment and delivery.

Stuck in the “early adopter” stage for the last decade, full-risk contracting is making the leap into the “early majority” in select markets (e.g., Minnesota; Portland, Oregon; Orange County, California) as Medicare Advantage enrollment exceeds 50 percent of Medicare beneficiaries. In those markets, enlightened payers and providers understand that market dynamics are shifting toward value-based payment and delivery. They want to position for this market shift, so they are aggressively pursuing vertical integration strategies to manage the healthcare needs of MA enrollees as well as to accommodate other full-risk contracting arrangements with governments, self-insured companies, and individuals.

These “early adopting” markets illustrate how bottom-up market reform will spread throughout the broader healthcare landscape. As individual markets achieve a critical mass of full-risk payment vehicles (e.g., comprising 25 percent to 30 percent of revenues), “early majority” health companies will vertically integrate payment and delivery capabilities to manage episodic and ongoing care for their members.

The science fiction writer William Gibson astutely noted, “The future is already here—it’s just not evenly distributed.”23 Gibson’s observation captures the uneven adoption dynamic of full-risk contracting. It also captures the inevitability of healthcare’s future “value-based” operating paradigm.

OLD MATH VS. NEW MATH

The combination of motivated healthcare buyers with full-risk contracting payment models creates a transformative force for revolutionary change in US healthcare. Without overstatement, this new demand-driven purchasing model for healthcare services is creating a “Copernicus” moment for healthcare. Copernicus presented the theory that the earth revolved around the sun, in opposition to established science that posited that the earth was at the center of the universe.

Despite rhetoric to the contrary, providers and payers have been at the center of the System’s FFS universe. They have artificially controlled the economics of healthcare payment and delivery for their benefit, not for the benefit of customers and consumers. After decades of operating in this System-centric universe, health companies are discovering that the payment and delivery of health and healthcare services actually revolve around customers and consumers. Empowered buyers insisting on value for their healthcare purchases are turning the healthcare world upside down and inside out.

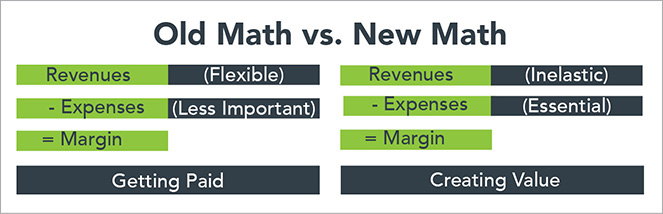

Healthcare needs a new math for this new age (Figure 5.3). Fee-for-service payment is healthcare’s old math. Revenues are flexible. Managing expenses is relatively less important. “Getting paid” is the principal managerial goal. Overtreating patients and manipulating billing codes are proven strategies for optimizing reimbursement. The System wins. The American people lose.

FIGURE 5.3 Health systems must change their focus from boosting revenues to controlling expenses and creating value.

In well-functioning markets, the supply of products and services offered adjusts to an intrinsic level of customer demand. Prices for commodity products and routine services are highly elastic. Higher prices reduce demand. Consequently, prices coalesce around fixed price points. In such markets, managing expenses effectively is essential for profitable operations. Robust cost accounting capabilities drive constant performance improvement, tight pricing algorithms, and efficient resource utilization.

In competitive markets, “creating value” distinguishes winning companies. They deliver high volumes of high-quality products and services at low prices with exceptional customer experience (think Amazon). Most healthcare services are routine. They occur frequently, have predictable outcomes, and invite standardization.

Under full-risk contracts, revenues are inelastic (generally fixed) and managing expenses is exceptionally important. Health companies participating in full-risk contracting must deliver necessary care within budgetary constraints or lose money. Since many full-risk programs incorporate customer choice, successful health companies also must deliver a great consumer experience to increase their market presence. This is healthcare’s new math, and health companies must learn it to be competitive in the post-transformation marketplace.

The realization that full-risk contracts will define the post-reform marketplace has triggered significant repositioning by “pragmatists.” The CVS-Aetna merger, the Advocate-Aurora merger, and the new Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway, JP Morgan (ABJ) health company reflect this emerging market dynamic. These companies recognize the need to enhance their full-risk contracting capabilities to accommodate increasing market demand among both buyers and sellers of healthcare services.

Revolutionary health companies aren’t waiting to attack the System’s inefficiencies. They’re creating value and going directly to healthcare buyers. They’re offering better healthcare products, competitive prices, and superior customer service. They have the forces of truth, beauty, justice, and value on their side. The best companies do even more than this. They develop a deep connection with their customers that reciprocates loyalty for solving their jobs-to-be-done. Meeting customers’ “Jobs” builds brand strength and sometimes even brand love.

TRUE BRAND LOVE—HEALTHCARE NEEDS TO INSPIRE IT

Customer-centricity and meeting customers’ “jobs-to-be-done” are the keys to retailing success. After all, business cannot exist without customers. While some companies do it better than others, meeting customers’ needs is standard operating procedure for businesses in general. Except, of course, in healthcare, where embracing consumerism is a new phenomenon.

In March 2016, I participated in a consumerism conference in Florida attended by senior executives from leading health systems. The conference was a nice break from Chicago’s winter weather and gave me an opportunity to gauge how health systems were approaching this brave new consumer-centric world.

Speaker after speaker noted increasing consumer frustration with healthcare delivery. These frustrations included high costs, poor service, poor communication, and constant administrative hassles. It was clear that health system executives in attendance understood that connecting with customers and improving customer experience are essential to building brand strength and organizational sustainability.

The conference included a riveting presentation on “brand love” by a global marketing director from Johnson & Johnson’s Consumer Products Division. She described brand love as “loyalty beyond reason” and stressed the benefits of establishing true connection between customers and products. For example, J&J began marketing Listerine as a cure for halitosis (“the reason some women never marry”) in the 1920s. From those modest beginnings, Listerine has developed full-out brand love with many of its customers. Customers’ hearts beat faster when they see a bottle. They pay premium prices for the privilege of gargling with the antiseptic-tasting mouthwash and enthusiastically tell their friends about all its other beneficial uses.

Brand love is emotional, not rational. For some reason I prefer Energizer batteries to every other brand. It makes no sense. Other batteries work just as well or better. Maybe it’s the Energizer Bunny (Figure 5.4). It just keeps on going!

FIGURE 5.4 The brand love for the Energizer bunny differentiates the company even though it’s selling a basic commodity.

Conventional marketing begins with “what” products companies sell. It then explains “how” those products differentiate from competitive offerings (why this car is better than that car) and concludes with a logic-based pitch for “why” customers should buy them. These rational appeals highlight product features and competitive prices. Yet, they rarely go viral and generate breakout sales. It’s too easy for customers, thinking rationally, to switch products.

Simon Sinek, the author of Start with Why, describes conventional marketing as “outside in.” This means starting with “What” the company is offering and “How” its product or service will make things better for the customer. For the marketer, “Why” the offering matters to customers is often little more than window dressing or an afterthought.

Sinek believes the best marketing starts with “Why” at its center and moves out to connect with “How” and “What.” Human beings are hardwired to respond to appeals grounded in purpose, trust, belief, and stories. The “Why” matters to people. It connects the brand to what they think, believe, want, and desire. The brand becomes an extension of their self-image.

In a widely viewed TED Talk, Sinek uses Apple to highlight the power of “inside-out” appeals that generate intense brand love. In reality, Apple is one electronics manufacturer among many competing for global market share. Conventional marketing would showcase images of Apple’s computers (the What) and highlight their elegant design, integrated operating system, and ease of use (the How) before making the Why sales pitch. Pretty boring.

Apple is anything but a conventional company. Apple’s marketing starts with the Why and works outward. Apple wants to empower individuals to make the world a better place. Apple demonstrates this through its computers’ elegant designs, integrated operating system, and ease of use. Same “How,” different context. Customers respond and flock to buy Apple products.

During the 2015 holiday season, Apple ran the “Someday at Christmas” ad with singers Andra Day and Stevie Wonder to promote its latest iPad. Here’s how iSpot.tv describes the ad:

Singer Andra Day joins the legendary Stevie Wonder to sing his classic 1967 holiday song “Someday at Christmas.” Without a band, Wonder sets up his Apple computer to record both the piano he plays and the vocal track. As Day and Wonder sing together, their family plays games, makes crafts and spends time together. To bring the song to a close, the youngest member adds her voice to the mix and then the rest of the family joins in.24

My eyes teared up the first time I saw this ad. During the same holiday season, Microsoft ran nonstop ads for its competing Surface Pro tablet highlighting all its great new features. Total “What” advertising. Nobody cared.

In Sinek’s words, people don’t buy Apple for what Apple does. They buy Apple for why Apple does what it does. By using Apple products, customers align with Apple’s values and project those values to the world. In so doing, customers begin to see themselves as they would like others to see them. Like all positive relationships, brand love increases self-esteem, confidence, and interconnectedness. It satisfies deeply human needs. People buy Apple products because Apple empowers individuals and enriches their lives. This enables premium pricing for commodity products.

Almost all advertising by health companies highlights great doctors, great technologies, and grateful patients. They feature the “what” and not the “why.” It’s hard to tell the companies apart. All health systems have great doctors, grateful patients, and believe in quality. That’s not enough to differentiate and build true brand love.

Back at the consumerism conference, the 20 participating health systems detailed their early efforts to engage consumers. Their initiatives were basic and included call centers, consumer-facing apps, and focus groups. With spring training for baseball occurring nearby, many presenters described their consumerism strategies as “being in the early innings.”

After the session, I joked with one of the J&J representatives that healthcare consumerism wasn’t in the early innings, that it was still in spring training. Without missing a beat, he responded, “It’s worse than that. They don’t even know what game they’re playing.”

Imagine how great American healthcare could be if health systems adopted Simon Sinek’s “start with why” philosophy and committed to making it an everyday reality. Brand love isn’t clever. It reflects deep trust between companies and customers built over years of interactive, mutually beneficial experience.

Customers reward companies that meet their jobs-to-be-done, tailor services, and deliver on their promises. Delivering value to customers and exceeding customer expectations have pushed Amazon to the pinnacle of corporate success. All because their empowered buyers keep coming back to Amazon for more and more products and services.

THE BIG IDEA: PUTTING CUSTOMERS FIRST

This chapter began by profiling Walmart’s healthcare strategies as both a customer and a seller of healthcare services. It ends by profiling Amazon, the digital retailer that is giving Walmart a run for its money. What both companies share is a relentless commitment to delivering value to customers.

Walmart became the retail juggernaut it is today by giving consumers more product choice, lower prices, and greater convenience. It pioneered big-box retailing, reinvented the supply chain, and gave customers exactly what they wanted. Amazon has challenged Walmart’s retail supremacy by using digital platforms to give customers even greater choice and even greater convenience at exceptionally competitive prices.

The fox knows many things,

but the hedgehog knows one big thing.

—Greek philosopher Archilochus, 700 BC

Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos is a classic “hedgehog” strategist. He runs his company according to one core principle: pursuing strategies that deliver value to customers no matter what. Every Amazon meeting contains an empty chair to represent the consumer. Bezos crystalizes Amazon’s vision succinctly: “We’ve had three big ideas at Amazon that we’ve stuck with . . . Put the customer first. Invent. And be patient. They’re the reasons we’re successful.”25

Amazon allows approved vendors to undercut its prices on its own website. Why? It generates better value for customers. Amazon will undercut these partner vendors if their profit margins become too high. Why? It generates better value for customers.

When Amazon entered the book publishing business, its worldview was both simple and devastating. The only irreplaceable components were authors and readers. Amazon’s technology could diminish and even replace publishers, distributors, and bookstores. One by one, publishing’s middlemen disappeared in multitudes.

Bezos wants Amazon to be the “earth’s most customer-centric company.” Amazon cultivates close and friendly relationships with its customers. Technology assists in personalizing services, but the culture of truly caring for customers has taken decades to nurture and grow. Consider the intimate way in which Bezos describes Amazon’s customers:

We see our customers as invited guests to a party, and we are the hosts. It’s our job every day to make every important aspect of the customer experience a little bit better.

It’s easy to love and trust the Amazon brand. Amazon delivers incredible value and overcorrects when it makes mistakes (which is rare). Imagine Amazon as an empowered buyer of health and healthcare services through its new partnership with Berkshire Hathaway and JP Morgan. Now magnify its impact as Amazon-like buying behaviors spread to other purchasers of healthcare services. It takes my breath away. It’s a world turned upside down. It’s revolutionary.

Empowered buyers with new full-risk payment models change everything in healthcare, and they should. Healthcare is deeply personal, intimate, essential, and sometimes scary. Consumers want to love and trust health companies. They want to believe payers and providers are on their side, acting in their best interest. With greater freedom to select health companies, consumers will gravitate to those that fulfill their jobs-to-be-done, make them feel special, and return their trust in equal or greater measure. Demand-driven change leads to Revolutionary Healthcare.