CHAPTER TWO

THE COHERENCE PREMIUM

Nearly every senior executive we talk to agrees that coherence is critically important. And yet companies everywhere are drowning in incoherence.

This is most evident when you look at the ways most companies set their priorities. Down from the senior executive team come financial targets intended to improve results. Each directive is well-intentioned and would be reasonable in itself, especially if the business units had a way to play that could guide them or a capabilities system that could deliver. But together, they often add up to an expectation of “surprise and delight” performance that is impossible to fulfill.

Faced with that expectation, business unit leaders do the only thing they can. They pick their objectives for growth with the most rapid probable returns, while nipping at whatever costs they find. They also demand the capabilities they need from functions like IT, human resources, R&D, and operations, to meet all the clashing imperatives they face.

Because these requests are disparate, and not driven from the company’s way to play, the priorities seem vague: “We need to be better in consumer insights,” or “We should be best in innovation.” There is no common view of what type of insights or innovation is truly important for the business.

The functional leaders try as best as they can to meet as many of the businesses’ needs as possible. They either distribute their limited investment and resources or request new investment to help them respond to new requests. Either way, this results in the company being “OK at everything, great at nothing.”

To manage the many deserving proposals they receive, top executives fall into the role of budgetary referee. In normal times, all the players get some portion of what they ask for. In bad times, everybody is cut nearly the same percentage, across the board. No group receives the full investment it needs to be distinctive. Nor is there any discussion about making the most of the resources available. Thus, many resources are either ill used or wasted outright. Some managers learn to take the proposals that don’t get funded and to resubmit them with a higher estimate of success. The company thus funds proposals that don’t fit its goals, and launches projects without giving them the wherewithal to follow through. The capabilities most relevant for strategic success are easy to sacrifice or shortchange, because there is little agreement about which of them are essential.

These problems with poorly used or wasted resources add up to what we call the incoherence penalty. It is all the more pernicious because it is frequently unrecognized as the source of poor performance. But it is apparent if you look for it.

You can hear the incoherence penalty, for instance, in the frustration voiced quietly by business unit and functional leaders. The head of a division or product line says, “I could do so much more if senior management stopped meddling and let me make more decisions.” The heads of operations, IT, human resources, and other functions complain, “I could deliver so much more if everybody sat down and agreed to set priorities.” But the underlying problem isn’t meddling, and consensus won’t make much difference unless the strategic logic of the business is sound. The root cause is a lack of coherence around the company’s strategy. Until this is dealt with, no organizational or cultural solution can possibly resolve the inherent conflict present in every decision.

Quarter after quarter, the lack of coherence generates poor results, which lead to even more pressure on performance and therefore more unrealistic expectations, more quick cuts, more inappropriate growth moves, and even poorer results. Eventually, time runs out. Management is changed, the company may be restructured or sold, and the vicious cycle starts all over.

Fortunately, as we’ll show in this chapter, the incoherence penalty can be reversed into a virtuous cycle. A deliberate, coherent strategy leads to more effective use of resources, to more powerful capabilities, and to greater returns, which reaffirm the value of a more coherent strategy.

We call this the coherence premium. While less prevalent than the incoherence penalty, it is just as recognizable. It manifests itself in very tangible ways: shareholder value, growth, operating margin, and a confident, optimistic corporate culture.

Tracking the Coherence Premium

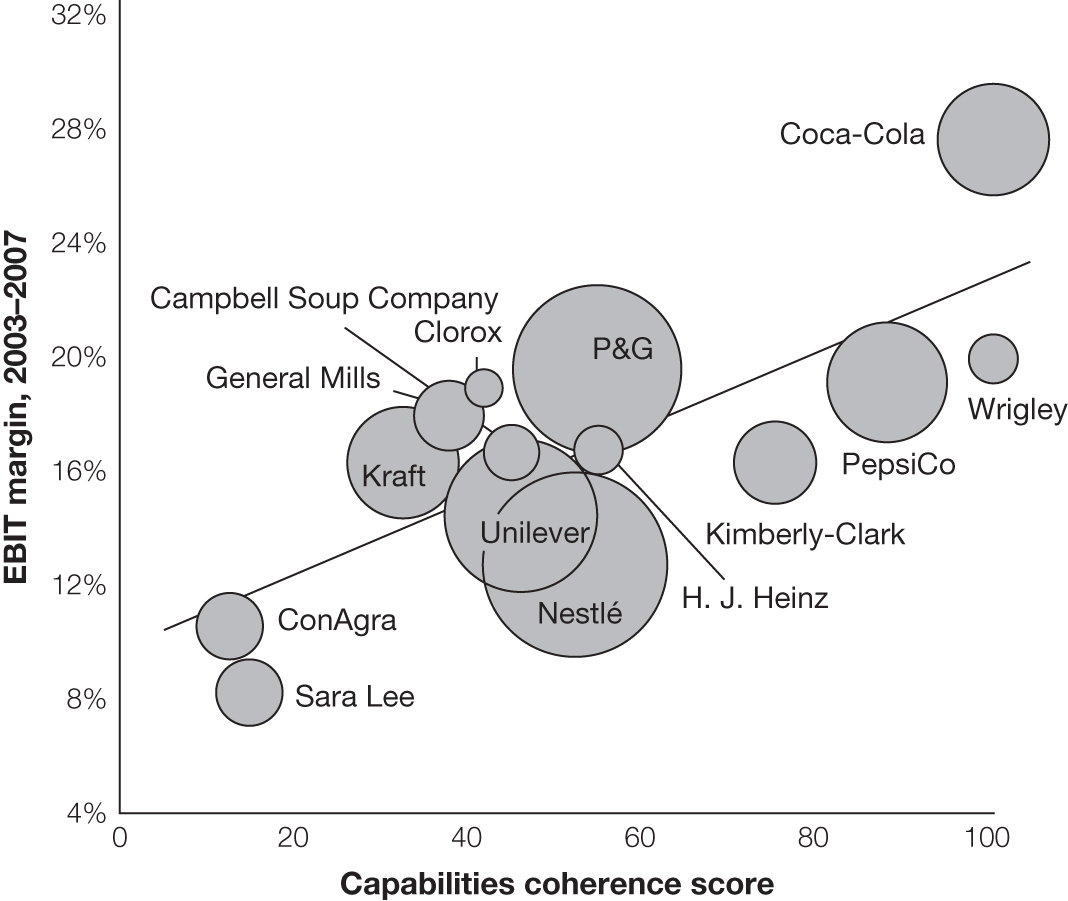

We have tracked the coherence premium in several industries, and the relationship between coherence and performance appears consistently. For example, an analysis of the consumer packaged-goods industry over five years of recent business history shows a clear link between coherence and financial returns (see figure 2-1).

The figure plots financial performance against coherence for fourteen major consumer-products companies. The y-axis shows financial performance, as measured in EBIT margin (earnings before interest and taxes, divided by net revenue). Similar correlations exist between coherence and shareholder value, though EBIT margins are more easily comparable across long periods of time.

On the x-axis, we rank companies according to a capabilities coherence score. This is based on the degree to which critical capabilities are shared across a company’s products and services. We obtained this score through a sequence of steps:

1. Identify relevant general capabilities (in this sector, they included rapid flavor innovation, in-store execution, etc.) for the companies being studied.

FIGURE 2-1

The coherence premium in consumer packaged goods, 2003–2007

An in-depth analysis of the consumer packaged-goods industry shows a clear correlation between coherence and financial performance. The size of the circles indicate relative 12-month revenue at the time of the study.

Source: Reprinted from Paul Leinwand and Cesare Mainardi, “The Coherence Premium,” Harvard Business Review, June 2010.

2. Break each company’s portfolio into distinct business segments (prepared meals, personal care, toys and games, candy and confectionaries, etc.).

3. Determine (through public information and proprietary knowledge) the relative importance of each capability to each business segment.

We based each company’s coherence score on how much that company’s capabilities varied in importance from business segment to business segment. If capabilities were important to most or all segments, the company ranked high; if most business segments had different capability requirements, the company ranked low. The scores were statistically adjusted for revenue, variations in segment size, and complexities related to international operations or other confounding factors. Although this formula doesn’t necessarily reflect the specific choices a company might make in its own capabilities-driven strategy, the score provides a reasonable proxy as seen from the outside.

The correlation is clear. The greater the coherence—the more market segments sharing the same critical capabilities—the greater the profitability. No matter how large or small the company, this correlation holds.

The standout performer is The Coca-Cola Company. This company is remarkably coherent, even compared with formidable (and relatively coherent) competitors like PepsiCo, Inc. All of the company’s beverages—carbonated soft drinks, sports drinks, health drinks, energy drinks, juices, teas, and coffees—rely on the same three key capabilities.1 The first is brand proposition: advertising and promoting some of the most ubiquitous and iconic product identities in the world. The second is store distribution, always a key focus and often direct to the store; Coca-Cola has a highly refined sales, merchandising, and delivery capability that enables it to execute at the retail level more effectively than its beverage competitors. This capability is linked to its third (and distinctively powerful) capability in franchising: overseeing and managing a global network of bottlers and distributors.

Together, these capabilities enable Coca-Cola to attract billions of people in more than two hundred countries. The company succeeds by building demand for products that only “The Coca-Cola System” (as it is called within the company) can deliver around the world. At times, Coca-Cola has flirted with businesses that don’t fit its strategy. For example, it purchased Columbia Pictures in 1982, but sold it to Sony just seven years later. The Coca-Cola Company always returns to The Coca-Cola System.

On this continuum, other relatively coherent companies with higher-than-average performance include Pepsi and the capabilities system of its subsidiary Frito-Lay; Wrigley, the gum-maker recently acquired by Mars, Inc.; and Kimberly-Clark, makers of disposable diapers, tissues, and other paper products. We will discuss these companies and their coherence strategies later in this book.

Then there’s Procter & Gamble. The position of this eminent consumer packaged-goods company in the center of figure 2-1 represents an average of its remarkable movement from the lower left to the upper right of the continuum in just over eight years. In early 2000, when A. G. Lafley assumed the CEO role, P&G’s stock price was falling, a decline attributed generally to an ambitious but failed expansion drive during the late 1990s.2 (Lafley’s appointment, then regarded as the elevation of a relatively young and inexperienced company insider, exacerbated the decline at first.2) At that time, P&G made and sold products in a variety of categories: diapers, laundry and cleaning products, health and beauty, feminine care, snack foods (Jif peanut butter, Crisco oil products, and Pringles potato chips), beverages (Folgers coffee and SunnyD drinks), food ingredients (Olestra), heat compresses (ThermaCare), and pharmaceuticals (such as the osteoporosis medicine Actonel).

P&G’s products might have succeeded more if they had all fit with the renowned capabilities system that it had spent decades developing. One component of that system was a world-class, technology-based innovation capability aimed at providing reasonably priced, life-enhancing or life-changing products that could be sold around the world. (Crest Whitestrips teeth whiteners and the popular Swiffer mop are two recent examples.) P&G also had a powerful international marketing capability, reaching consumers in many countries who were all attracted to the same types of benefits. This capabilities system formed the basis of a highly consistent global consumer-product machine, lining up perfectly behind iconic brands such as Crest, Tide, and Pampers.

But the system was not a natural fit with all the products in P&G’s portfolio. For example, highly innovative foods and beverages could not, over time, easily hold their own in a category dominated by merchandisers that pushed out more flavors to more supermarket shelves in a lower-cost model. This was true even of Pringles, where their capabilities system had developed the innovative and consistently shaped “potato chips in a can” with an army of loyal devotees. Moreover, tastes in snacks and beverages tend to vary from one region to the next, so P&G’s global marketing model wasn’t always as effective as it was in non-food categories, especially against competitors who could more easily adjust their packaging, flavoring, and messaging to match local markets. Most importantly, while P&G’s product lines tended to be strong competitors individually, the differences among them made the company relatively incoherent as an organization, and that dragged down its advantage. As Lafley later recalled, “[P&G’s] people were not oriented to any common strategic purpose.”3 His job, he said, was to decide what business P&G was in—and what it was not in.4

Under Lafley and his successor, Robert McDonald, P&G sold off most of the products that would be better supported by other capabilities systems. These included its pharmaceutical division and most of its food divisions, even though some of these were performing well at the time. Lafley and his executive team then focused on strengthening P&G’s most important capabilities: for example, boosting its R&D effectiveness with open-innovation initiatives that allowed the company to draw on ideas from all over the world. They also focused on developing or acquiring product segments that would benefit from the company’s distinctive capabilities—for instance, by purchasing Gillette in 2005. P&G’s stock price has tripled since 2000; the commercial success rate for new products now runs between 50 and 60 percent (compared with 15 percent in 2000); and Lafley, the “inexperienced insider,” was recognized for his management insight in a variety of venues, including being named executive of the year by the Academy of Management in 2007.5

Down at the bottom left of the coherence spectrum reside ConAgra and Sara Lee, and a quick scan of their product portfolios indicates why. Because both companies have complex portfolios assembled through decades of acquisitions, the businesses require a wide range of capabilities in support. For example, during the earlier years covered by this analysis, Sara Lee’s product lines comprised its own branded baked goods, Ball Park hot dogs, Hanes underwear, Kiwi shoe polish, Brylcreem hair care products, Coach luggage, Best’s kosher meats, a variety of food service operations, and many other product lines. Sara Lee historically applied a highly decentralized management model to manage all this and thus employed a wide range of capabilities. The food and beverage categories required various forms of product formulation, packaging, sourcing, and supply-chain prowess, while the company’s household and personal care products deployed entirely different operational, marketing, and distribution capabilities. To add a further level of complexity, the company’s product line varied by geography. All of this has been reflected in the company’s relatively low financial performance.

Under the leadership of Brenda Barnes, who became CEO in 2005, Sara Lee has begun to seek more of a coherence premium.6 The company has focused its attention on branded meats, food services, coffee, and baked goods, spinning off most of its other businesses and developing strategies based on deploying common capabilities for its products within each category.7

You might conclude from this that being a large corporation with a single-category high-margin product line, like The Coca-Cola Company, is the key to having a high coherence score—and hence to success—but the analysis shows that the benefits of capability coherence are not limited to this kind of scale. Small players such as Wrigley (before its 2008 acquisition by Mars) and complex players like P&G also have high coherence scores. In general, factors like size, scale, and even the number of products and services matter less than the company’s choices about the three strategic elements.

An analysis of the automobile industry over a comparable eight-year period produced similar results. Here again, when capabilities were matched with car brands and segments, the companies with the most consistently applicable attributes—Porsche, BMW, Toyota, and Honda—were also the best financial performers.

The same correlation also holds true for other industries, such as financial services, telecommunications, and health care. In every test we have conducted so far, there is a coherence premium, and the premium accrues to any company that moves along the continuum to align its way to play, capabilities system, and product and service fit.

Four Sources of Value

Why is coherence essential to sustained performance for your company? How does it produce the benefits that we saw in a variety of industries? We have found four specific, observable ways in which coherence generates value: effectiveness, efficiency, focused investment, and alignment.

Effectiveness

One consistent effect of a capabilities-driven strategy is renewed emphasis on, and continuous improvement of, the most relevant capabilities. Day in and day out, you become more effective where it matters most. You “sweat” your capabilities, refining and developing your methods and processes. Because your capabilities reinforce one another in a system, they improve more rapidly than those of your more scattered competitors. Not only do you gain in operational excellence, but you also become more skilled at making the right choices. In a competitive environment, this gives you an increasing edge; as you advance, other companies find it more and more difficult to catch up.8

Becoming more effective is a key component of your company’s right to win against competitors. Your people become more skilled; your systems grow more adept; your profitability improves. Customers are attracted to you because of this added value for them, so your share of the market increases as well. Sooner or later, this leads to a second-order gain in effectiveness: success accrues to the successful. As you become perceived as a market leader and a source of excellence, you attract more and better customers, business partners, employees, leaders, and long-term investors. With all of these to draw on and learn from, your capabilities improve even more. This creates a lock on value that is enormously difficult for competitors to replicate.

Efficiency

As you apply your capabilities more broadly across more products and services, you get more value out of them. Your investment in each of them goes further. You can afford to hire a team of specialists in online marketing, to recruit a senior vice president who really knows the health industry, or to build a state-of-the-art supply chain, because the costs of building capabilities, which can be very high, are amortized across your entire portfolio. Small parts of your business, which could never afford these capabilities if they were separate, can take advantage of them with you.

Depending on your way to play, your ability to deploy capabilities at a lower cost can provide a pricing advantage, catalyze higher margins, or enable you to invest more in these important capabilities. There is far less duplication of effort as well; you’re less likely to have different business units installing separate IT systems because they each need different features. Meanwhile, your less coherent competitors must bear the expense of disparate capabilities for every one of their offerings.

Focused Investment

A coherent system makes the most efficient use of your resources, attention, and time. You spend the most where you need the most. By allocating capital and expense more deliberately and effectively, you focus more on the capabilities that differentiate your company competitively and less on what Gary Hamel and C. K. Prahalad called “table stakes”—the necessary competencies and skills that every competitor brings to this market.9 Moreover, you avoid the expense of investments that breed incoherence. You don’t, for example, make accounts payable world-class; you don’t fund unnecessary R&D projects or marketing campaigns. You invest in depth where depth is needed, and go light where you should go light.

Here, too, a virtuous cycle kicks in. As your company’s staff become more aware of the impact of focused investment on growth, they become more motivated to participate. We have seen R&D meetings, for example, where the project leaders get excited about a particular idea. Then someone says, “Hang on. That won’t thrive in our capabilities system,” and the company avoids the time and expense of considering an incoherent funding request. Meanwhile, ideas that might have been overlooked or discarded, but that fit the company’s strategy, can get their moment in the sun.

Alignment

When you commit to a strategy and articulate it clearly, then everyone has a common basis for the day-to-day decisions they make. Throughout your company, people in different businesses and different geographic areas are attuned to the same capabilities system and way to play. They are thus more likely to understand one another, and to make independent decisions that are nevertheless in sync. They combine forces and share resources more easily. They execute faster and with more force, because they are not held back by concern about what their colleagues might think. More coherent decision-making becomes part of your company’s culture. The advantage this gives you over smaller-scale or less coherent competitors is palpable.

One often-unexpected result is the ease of attracting and retaining high-quality talent in professions related to your capabilities system. These highly skilled people—be they engineers, traders, researchers, analysts, designers, lawyers, physicians, or specialists of any sort—will find opportunities in your company across a wide range of products, services, businesses, and parts of the world. This means they will have more opportunity for advancement, more recognition within the company, many opportunities to practice their craft, a large network of peers, and the enhanced reputation and day-to-day fulfillment that comes from all of these factors. Recruiters and candidates know this, and the best people in the most relevant fields will be drawn to work for or with you.

____________________

All four of these sources of value reinforce one another. Alignment makes it easier to integrate people across the company, which leads to greater effectiveness as people learn from their colleagues. An ethic of careful investment leads people to find ways to use their capabilities in more parts of the organization. Before too long, your company can grow at a faster pace, and at lower cost, than it ever could before.

Absolute and Relative Coherence

How much will your company have to change to experience these benefits? That depends, of course, on how coherent you already are. Unquestionably, a company that ruthlessly looks at its business, aligns everything closely to a focused and powerful capabilities system, and divests the products and services that don’t fit will start to see the coherence premium kick in very quickly.

But you do not have to go that far. In many cases, it may be unrealistic to try. To realize the value of the coherence premium, you simply need to be relatively coherent: to align your way to play, capabilities system, and lineup of products and services better than your competitors do. In any given industry, with all other circumstances being relatively equal, a more coherent company generally outperforms a less coherent one.

The key is to make hard choices about the elements in your system. It is very difficult to develop three or four, let alone six, truly differentiating capabilities. More than six, in our view, is probably unworkable. Prahalad and Hamel came to a similar conclusion: “Few companies are likely to build world leadership in more than five or six fundamental competencies,” they wrote.10 Similarly, while some companies deliberately develop two ways to play, with capabilities systems to match, this is a more expensive and distracting path, with less of a coherence premium, than focusing on one.

You do not need to commit everything to a single way to play immediately. Road blocks and realities may make a single focus impractical, particularly in the short term. Again, there is great value in relative coherence. If you have two or three ways to play, each with its own capabilities system, and your products and services are lined up accordingly, you will have a great advantage over competitors with ten or fifteen separate and unrelated businesses and no common capabilities system at all.

Is Coherence Right for Everyone?

As we explored the value of coherence, we found four types of conceptual challenges—concerns raised about the applicability of this approach to every type of company. Some question the value of coherence in a struggling industry, like airlines or chemicals. Others argue that in a global environment, where companies must operate in many geographic locations, a single way to play and capabilities system cannot apply. The third group, typically thinking of emerging markets, wonders if the idea of capabilities applies to places where the dynamics of government involvement and competition are distinctively different from the more mature economies of the West. The fourth argument raises the experience of conglomerates: are there not companies that can manage multiple businesses, with multiple ways to play, more effectively than their single-business counterparts?

These four arguments are similar, in our view, because they reflect an implicit assumption that the complex trade-offs in business today are unresolvable. Many businesspeople assume that they must live with the limits of incoherence: in their industry, their geographic locations, or their own company. To us, these seeming limits are really signals of strategic opportunity. If your company is wrestling with incoherence in its geographic expansion or its mix of products and services, then chances are your competitors are as well. By marshaling a capabilities-driven strategy and moving toward coherence, you may have a chance to move past the constraints that have, up until now, defined the way your business or industry operates.

Let’s look at these four arguments in more detail.

Troubled Industries

Many managers have taken to heart Michael Porter’s admonition about the relationship between the competitive structure of an industry and the profitability of companies within it. If the forces shaping industry structure “are intense,” he wrote, “as they are in such industries as airlines, textiles, and hotels, almost no company earns attractive returns on investment. If the forces are benign, as they are in industries, such as software, soft drinks, and toiletries, many companies are profitable.”11

Though Porter took pains to explain that industry structures can change and can be shaped by the actions of leading companies, he has often been interpreted as saying that some industries are innately good, while others are irredeemably bad. If you’re in a tough business—or, conversely, if you’re in a protected industry, like electric power, which in many countries is isolated from ordinary economic realities—then there’s no real advantage to having a distinctive way to play or capabilities system.

Yet look more closely at the airline industry, a field bedeviled by high operating and labor costs, varied global regulation, oscillating fuel prices, and high vulnerability to storms, natural disasters, and terrorism. Who could make money in that business? Nonetheless, a study of publicly held airlines in 2009 found twenty with reasonable levels of financial health. Ryanair, Singapore Airlines, easyJet, AirAsia, and Southwest Airlines were at the top of the list.12 Southwest Airlines, Ryanair, and Singapore Airlines, in particular, are known for their distinctive, well-matched systems of capabilities. They don’t do things that don’t fit their way to play. Similarly, in the 1980s, steel and aluminum were considered inherently cyclical businesses, doomed to debilitating downturns—until Nucor, with its minimills, and Alcoa under Paul O’Neill, proved otherwise. In short, even in a competitively intense industry, you can find a coherent strategy that causes enough differentiation that you can create a high level of value.

To be sure, many businesspeople see these cases as outliers—as rogue companies that somehow escaped the strictures of a bad industry. But from a coherence perspective, these companies found effective ways to play that didn’t just escape industry dynamics, but also changed them. Increased coherence often creates value by changing the industry structure. Over time, through mergers and acquisitions (including the acquisition of failed competitors), products and brands often migrate to the companies with the capabilities best equipped for them—typically the companies willing to pay the greatest acquisition premiums for products and services that fit. As they differentiate themselves, the most coherent companies take dominant positions, and customers migrate to them—leading to more sustained advantage for clearly differentiated competitors.

That is what happened in the diaper wars, a well-known marketing battle of the consumer products industry. Starting in the late 1970s, there were two leading producers of disposable diapers. Procter & Gamble, which invented Pampers disposable diapers and launched them in 1961, and Kimberly-Clark, which entered the category with Kimbies in 1968, launched its better-selling Huggies brand in 1978 and became the market leader in the early 1980s. The two firms competed fiercely on both price and such innovations as fasteners, increased thinness, leak guards, and fit improvements. This provided consumers with great performance and value, at ever-lower prices, but it also limited the profitability of the category.

As time went on, however, the two companies began to differentiate, starting with their technology. Disposable diapers are remarkably complex, highly engineered products, combing advanced adhesives, waste-treatment chemicals, and the layering of paper, plastic, and cellulose pulp. The diapers must hug the infant, absorb human waste, draw it away from the skin, mask the smell, prevent leaks, fit under clothes, and promote health and comfort.13 Both companies assured consumers that they had all these features, but each emphasized different qualities in the final product. Thus Procter & Gamble’s way to play focused on claims that its diapers prevented more leaks and unwanted accidents. This was backed up by the company’s solid capabilities system: its prowess in technology and global marketing. Kimberly-Clark was more of an experience provider; it offered a more emotional connection to mothers with a different marketing message, distributed through more media channels, emphasizing the diaper’s remarkable fit, sizing system, and reputation for comfort.

As P&G and K-C deployed their different technological and marketing capabilities, the two sets of attributes, increasingly distinct, attracted different customers. A third group of customers, the most cost-conscious purchasers, drifted to private-label store brands. Gradually, the price wars abated; though the segment remains highly competitive, profitability for both P&G and K-C improved. Without collusion, the sector evolved, driven by differences in ways to play and capabilities systems.

Something similar may be happening right now in the specialty chemicals industry—the makers of the ingredients in such products as inks, coatings, paints, and solvents. Since the mid-1980s, like the chemicals industry in general, this group of companies has faced maturing markets, increasing commoditization, more demanding customers, new competitors (currently emerging in the Middle East and China), and a diminishing pipeline of new products as the innovation rate in the chemical sector has generally declined. In this environment, it has sometimes seemed as if there is no option but to compete on price, with lower margins and less investment in R&D.

But it’s now becoming clear that there are several ways to compete. Some businesses, like Reliance Industries and LyondellBasel Industries, are low-cost value players, producing bulk chemicals to be delivered in quantity. Others are customizers: they tailor their existing products for individual customers in particular industries, helping them solve particular problems—for example, making paints and coatings to the specifications of particular automakers, or thermoplastic-enhanced compounds for aerospace companies. A third group is basing their business on customer-centric innovation: designing new “solutions and materials,” as they call it, specifically to fit the individual needs of their manufacturer customers.

Each of these ways to play requires a very different capabilities system. For example, in purchasing GE Plastics, SABIC (Saudi Basic Industries Corporation) has been forced to move from being purely a value player to also operating as a customizer (and a solutions provider in some segments). In some cases, this means significant change or major new investment. But the specialty chemical companies that focus on these ways to play, rather than looking for business wherever they can find it, are beginning to generate better returns; the industry’s customers are migrating accordingly, and the overall structure of the industry appears to be changing to reflect those ways to play.14

Multiple Geographic Areas

A commonly held belief in mainstream business is that global expansion is not only attractive (particularly in capturing the high growth rates of emerging markets), but also required. After all, that is how companies gain scale. But as IESE Business School professor Pankaj Ghemawat points out in Redefining Global Strategy, many companies have lost a great deal of value by proceeding as if “borders don’t matter . . . [They are] most likely to compete internationally the same way that [they] do at home.”15

We agree with Ghemawat that the world is in a state of semiglobalization. In other words, although communications, finance, and transportation links have made the world “flatter” than it used to be, the differences from one country to the next are still formidable. Even within regions, such as Western Europe or the Middle East, there are great differences in culture, labor relations, access to labor, government policy, and infrastructure (including distribution channels) from one country to the next. Your ability to manage these factors depends, in part, on the capabilities demanded by the conditions in a given locale. A telecommunications company, for example, depends on local landline infrastructure and is governed by strict regulation. It requires different capabilities when those factors vary, as they often do between countries. For all these reasons, your way to play in some geographic areas may be incompatible with other areas.

Nonetheless, this doesn’t mean that you should apply a different way to play and capabilities system everywhere. Companies that develop a geographic strategy based on coherence—expanding where their capabilities system applies—have a natural advantage. Some of the first companies to master this in emerging markets, for example, are the “new blue chips,” businesses that start in one emerging region and become global powerhouses elsewhere by drawing on the capabilities systems that they mastered in their home countries.16

Gruma SA, a company headquartered near Monterrey, Mexico, typifies this group. In Mexico, Gruma produces corn flour and related products, but around the world, it uses its capability in food processing—the ability to roll any kind of flour into salable flatbread—to great advantage. The company sells corn tortillas in Latin America, naan in India and the United Kingdom, and rice wraps in Beijing. In 2006, Gruma invested $100 million in a new Shanghai manufacturing plant, selling flatbread to Japan, Korea, Singapore, Thailand, the Philippines, and China.

“In the first stage,” said Gruma chairman Roberto Gonzalez Barrera, “we will supply the continental China market, gradually increasing our range to the European and Asian borders of the Middle East. To us, this is a long-term investment that will lead to strategic new business opportunities.”17 As we’ll see in chapter 7, this focus on capabilities (in Gruma’s case, advanced manufacturing and marketing of flour and flatbread) provides a much better vehicle of expansion than more conventional “adjacency” moves, such as producing frozen meals that use tortillas. Those would require vastly different capabilities.

The Beijing-based Li Ning athletic shoe and apparel company provides another example of a company parleying distinctive capabilities into a carefully tailored geographic expansion. The company was founded by its namesake, Li Ning, a very famous Chinese Olympic gold medalist in gymnastics. It based its first moves out of China, into France and Argentina, on the capabilities deliberately built up by its founder for the Chinese market: rapid product introductions; inexpensive manufacturing; fast-follower design; and audaciously competitive, sports-related marketing (with a special emphasis on team sponsorships in countries outside China, including basketball in Argentina, Spain, and the United States). The company’s most visible marketing coup occurred at the 2008 Summer Olympics in China, when Li Ning himself lit the torch at the opening ceremony. Though the company was not a sponsor of the games, its name was heard around the world when he was introduced as its founder—a blow to Adidas, which had spent hundreds of millions on Olympics-related sponsorship and marketing. Then in 2010, the company opened its first American store, choosing Portland, Oregon—Nike’s home turf—as the location.18

Another example from China is Huawei, one of the world’s leading telecommunications equipment manufacturers and network services providers. Founded in 1988 to serve Chinese markets only, it expanded geographically after 1996, starting with Hong Kong. By 2004, most of its revenues came from outside China. Huawei started out producing switches and routers that were considered “just good enough” technologically for emerging markets, but they were inexpensive, up-to-date, and brought to market rapidly. Over the years, as Huawei increased the quality of its equipment and entered more industrialized countries, it still kept prices low and operated as a value player. Although this way to play sometimes led to accusations of intellectual property theft, its net effect was a rise in the standards for inexpensive telecommunications equipment everywhere.19

In short, the value of coherence grows when a company expands across those geographic boundaries where its way to play and capabilities system are relevant. When considering new geographies, look for places where your distinctive capabilities can give you a right to win—and be skeptical about growth strategies that require an ever-expanding list of things you need to do well, just so you can compete everywhere. Being clear-minded about what your enterprise does well will be all the more important as markets continue to globalize and customers around the world have more access to information and goods from abroad. Seeking higher quality and lower costs, customers will gravitate toward products and services that provide better value, which inevitably means more attractiveness for companies with more coherence.

Emerging Markets

Sometimes people ask us if the need for coherence applies in emerging markets like Brazil, India, and China. These countries are typically hotbeds of entrepreneurialism, where startups must respond to opportunity rapidly and decisively. They seemingly can’t slow down and focus on one capability system and way to play. These countries also tend to have highly active governments with idiosyncratic rules; success apparently depends less on business-related capabilities than on having good relationships with key officials and finding a protected niche in which to operate. As many outside companies entering emerging markets have discovered, it is very difficult to compete with either highly entrepreneurial locals or locals who enjoy government-sanctioned privileges. Why bother with coherence?

But this view is, in our opinion, misleading. A coherent capabilities system and way to play are more valuable in emerging markets than they might seem to be at first glance. The capabilities systems don’t always look like those you would find in Europe or North America, but they can be just as focused, distinctive, and tied to a way to play. When the U.K. grocer Tesco entered Thailand, for example, it discovered that it could not easily supply fresh produce long-distance, as it did in its home country. Given the country’s traffic congestion and poorly maintained roads, conventional refrigerated vehicles were impracticable. It was much more effective for Tesco to build another capability: sourcing fresh food from local growers, who existed near just about every store. This became a critical component of Tesco’s strategy in Thailand and was so successful that Tesco became the largest food retail chain in the country. The strategy was later emulated in India by the large Indian retail chain Reliance.20

Many emerging-market enterprises compete by grounding their strategy in an in-depth understanding of the local market, that few outsiders (or insiders) can match. Their distinctive capabilities include not just dealing with regulation, but distribution, labor management, guerilla marketing, and inexpensive on-the-ground innovation. A good example is the China division of the global restaurant chain KFC (also known as Kentucky Fried Chicken, owned by Yum! Brands), which operates more or less as a self-contained business. As Edward Tse notes in The China Strategy, KFC is one of the most successful retail chains in China, even though it came from another continent with food, like fried chicken, that originally seemed alien to the Chinese culture. It took ten years for KFC to develop the capabilities it needed to be profitable in China, including the capability of finding and continually improving a menu adapted to Chinese taste, customs, and habits. Other critical capabilities included a dedicated logistics and distribution network—no easy task in China in the late 1990s. The restaurant also invested in ovens, so that KFC could offer more than fried food, and other technologies unique to the brand. Tse argues that it made a great difference that the company’s China Division president Sam Su understood the Chinese culture and food business intimately. Even today, according to a manager who works for Su, “it takes five years for a local manager to develop an in-depth understanding of how to manage a Western-style fast-food restaurant.”21

Many companies in emerging markets adopt a way to play as regulation navigators. They design their businesses to thrive by following (and influencing) governments rules and oversight, with capabilities to match. Regulation navigators exist all over the world, including in industrial economies, often in such sectors as health care and electric power. But it’s important to remember that even the most monopolistic or regulated systems may eventually be deregulated. The forces of capitalism are simply very strong. When the moment of deregulation comes, the speed can be sudden and the dislocation can be severe; shares reallocate fast, and the better capabilities system will win at that time.

One company that discovered this firsthand was the Russian mobile telecommunications company VimpelCom, which competed for customers in 2003 after the privatization of the Russian telecom industry. Then-CEO Alexander Izosimov, looking back at this period, said that 80 percent of his company’s market share was determined by its success during “hypergrowth,” his name for this brief, frenetic, transition. “It’s an experience that either kills your company or makes it stronger,” he writes. During his company’s first bout with hypergrowth in 2003 in Russia, “every meeting was a crisis meeting and every decision was made on panic mode.”22 Companies that have explicitly thought through a way to play and developed some of the entrepreneurial capabilities they will need will be far more advanced than competitors when this, or any other abrupt discontinuity, occurs.

Complex Conglomerates

Most large companies are already in several major businesses; some of these are multibillion-dollar businesses in their own right. Given this reality, must every company limit itself to one strategic trio—one way to play and one capabilities system, with all products and services matching? Haven’t some conglomerates shown that they can operate with multiple strategies? GE, Textron, United Technologies Corporation, and Tata, for example, have built their strategic approaches on taking disparate businesses and knitting them together with their own versions of managerial glue: operational prowess, leadership development, effective allocation of capital, corporate culture, and the clout of their size and reputation. Aren’t these businesses more effective together than they would be on their own?23

Perhaps. But in our view, the greatest value an enterprise can provide its parts is the delivery of a capabilities system. Being large, especially for the sake of scale, will in itself not add to that value, and will probably not win the day in the long term. The burden of proof is on the enterprise to show that being part of it adds more value than the incoherence penalty destroys. (The well-known conglomerate discount is the stock market’s way of demanding the same proof.)

While many look at GE as proof that a diverse company can be successful, one great advantage for GE has been its relative coherence. When Jack Welch became CEO in 1981, he began honing down the company’s portfolio from 150 businesses to 15.24 GE’s famous managerial initiatives, such as Workout and Six Sigma, spanned all of its businesses and provided the glue that other conglomerates lacked. Welch’s name for this form of coherence was “integrated diversity.”25 It made GE a better competitor than most of the large companies that it went up against during that time; while most of those competitors had a narrower range of products and services, they were more incoherent.

In recent years, GE’s industrial businesses, such as medical systems and industrial equipment, have done consistently better than its service businesses such as GE Capital, Kidder-Peabody, and NBC-TV. GE executive alumni have also tended to fare better in industrials and manufacturing than in financial services and retail companies. Could these be indicators that GE’s coherence is grounded in capabilities like technological innovation and process improvement, which are more applicable to engineering-intensive businesses (like Honeywell, 3M, and Cooper Industries, successfully run by GE alumni) than to service businesses (like The Home Depot and Conseco, where GE alumni, taken on as CEOs, were ultimately forced to resign)?26

We suspect that it will get more and more difficult to maintain coherence across a range of businesses as broad as GE’s. Moreover, the business world has moved on since Jack Welch’s heyday, and if you are a leader in a large, multibusiness conglomerate, you undoubtedly face more coherent competition than you did in the past. If you are interested in raising an inquiry about your own coherence, there are two ways to start.

One starting point is within an individual business unit, where you can create a pocket of coherence: a self-contained operation with its own way to play, capabilities system, and lineup of products and services. Then begin to explore how the resulting coherence can spread, through functions and related product or service lines, to the rest of the enterprise. This strong starting point provides a platform for thinking about which parts of the business fit, which might be better off elsewhere, and why.

Alternatively, establish a top-down rationale for the structure of your corporation. Ask yourself: What are the sources of value that justify all of the businesses being part of the same corporation? They may already share services like human resources, finance, public relations, and regulatory compliance, and you may feel that these represent a form of glue. But are they the distinguishing capabilities that set your company apart from others? Do they reinforce one another, and are they aligned with a chosen way to play? Are they the system of capabilities that you would choose if you were starting from scratch, or are they simply the capabilities that are convenient to share right now? If the capabilities you share are not distinctive, then it may well be that the days of conglomerate benefit for your company, if they ever existed, are drawing to a close. A form of capabilities-driven strategy, in which different parts of your business become separate companies, each with a different way to play and capabilities system, may be the answer you are looking for.

The Path to Value

Given the complexities of incoherence and the choices necessary to move toward coherence, every company will find its own path. However, there are some universal principles to be aware of as you plot and take this journey.

The next chapter explains the basic process and stages of the capabilities-driven strategy. This is the path for increasing your coherence, becoming more coherent than your competitors, and gaining the corresponding value for your company.