CHAPTER TEN

THE ESSENTIAL ADVANTAGE ROAD MAP

In this chapter, we lay out the road map for a capabilities-driven strategy initiative: the journey to essential advantage. Having come this far, we assume that you recognize the value of this approach, and that you already have an idea of your relative coherence, compared with competitors. Perhaps you have already taken the Coherence Test (table 3-1). In any case, you are ready to develop a more effective way to play and a capabilities system and draw them together with your critical products and services.

A handpicked team of core people should by now be dedicated to the strategy process, overseen by a team composed of most or all of the senior executives of your company. During the next several months, these two groups will work through the five stages of activity that we described briefly in chapter 3. These are: discovery (developing a comprehensive understanding of your situation and formulating hypotheses for your way to play); assessment (testing and refining those hypotheses); choice (making a full commitment to an overall strategic direction); transformation (setting in motion the actions needed to bring that strategy to life); and evolution (continually developing your new strategy and further creating and capturing value).

This design reflects a shift we see in business today—from treating strategy as an answer, handed down from a group of experts (inside or outside), to strategy as an ongoing process, with the management team and business leaders engaged and driving the organization forward.

Before Beginning the Journey

As your first important decision, consider your scale and scope of activity: where to begin and what markets to address. Specifically, will you conduct this work at the full-enterprise level or within just a part of your company? (That part could be a business unit or a group that faces a single market.)

Starting at a more local level won’t move your entire organization to full coherence, but it is often an easy and pragmatic entry point for strategic change. You can test the waters here before committing the enterprise to an overarching strategic shift. A business unit can then become a pocket of coherence: a springboard for broader change. Be sure to explicitly identify the part of the organization that will participate, and the markets you hope to address, so there is no confusion about who is involved.

If the senior management and board are interested in major performance improvement or a leap to new forms of growth, then you might begin with a full-enterprise exercise, working across multiple business units and divisions to develop a common capabilities-driven strategy. This process is typically as all-encompassing and intensive as a major reorganization or merger. In one such initiative for the North American unit of a company with more than a half-dozen lines of business and annual revenue in excess of $10 billion, there were eighteen planned workshops and input sessions in a span of four months, including two board discussions. Though it may start at the corporate center, an enterprise-wide capabilities-driven strategy initiative will expand to involve discussions in every part of your company. (For more detail about enterprise-level strategies, see the end of this chapter.)

Whatever its scale, a capabilities-driven strategy requires the full approval and involvement of those to whom you’re accountable. At the enterprise level, this means the board. Before you begin, gauge the board’s appetite for near-term profit trade-offs—giving up seemingly profitable businesses or making investments now for the sake of coherence and its benefits later—and for capital-structure changes if your agenda calls for acquisitions. At a business-unit or other local level, you’ll need the CEO’s and senior executive team’s wholehearted endorsement, especially as you make some of those same trade-offs.

You’ll also need engagement from below. People at every level will not just execute your strategy, but also conceive and develop new approaches and applications. If they misunderstand the intent of your way to play, they will not make decisions effectively. As the number of people involved in this strategy grows, you will reach coherence only by gaining the support of the natural leaders among them.

The entire process could take weeks, or months—perhaps six months or more. You need time to iterate, test, and confirm your views, and most of all to gain the confidence to make a full commitment to your new strategy. If you expect your strategic choices to have significant impact, then this time will not be wasted. The “Checklist for Starting the Journey” poses further questions that will help you embark on this initiative.

The Discovery Stage

Like the discovery phase of a legal case, this stage involves setting a context for action. It takes place through a series of intensive, highly engaging discussions and workshops: optimally conducted over several weeks with the same core team of ten to twenty people. In these sessions, you explore and develop a shared understanding of three basic realities that affect your way to play: your customers and competitors (a market-back view), your potential growth opportunities (an aspirational view of market attractiveness), and your own distinctive strengths relative to your competitors (a capabilities-forward perspective). From all of the complexities inherent in these realities, you synthesize a group of clear, cogent hypotheses: each one a potential way to play that could be viable for you.

The first three substeps of the discovery stage—focused respectively on market, growth, and capabilities—can be conducted either in sequence or in parallel. They must be separate enough that the team benefits from disparate perspectives, and intertwined enough that ideas can be carried from one to the other. This is not a cumbersome, “boil the ocean”–style deductive process in which you gather and analyze mountains of new data. Rather, it’s an inductive approach in which you draw on the insights you already have to brainstorm and explore potential ways to play. In the fourth substep of this stage, when you bring together the insights you have gained, you will have a chance to settle on the three to five hypotheses that you will assess more closely in the next stage.

In all the discovery-stage sessions that you conduct, make it a goal to develop greater clarity about your own business. An open tone and candid informality is as important as the content. Don’t dismiss any hypothesis too rapidly; perhaps it contradicts your ingrained way of thinking, but reveals challenges or opportunities that you shouldn’t overlook. Make room for blue-sky thinking; if it helps, draw on examples of remarkable innovative leaps, such as P&G’s Swiffer mop or Tata’s $2,400 Nano automobile. Cultivate an expanded definition of your business (you don’t sell copiers; you’re in information management). Then come back to earth to think more pragmatically about your business realities today.

Market-Back Discovery

As in any “market-back” study, focus on customers, potential customers, regulators, and competitors. In several different exercises, you gain a more focused understanding of your business context and how the world is changing. In the process, hypotheses for potential ways to play will emerge.

Winners and losers: Use the coherence test template (table 3-1) to look closely at your competitors’ market position compared to your own. Who is the market rewarding—in other words, who has a right to win? What ways to play have they adopted? (Combine the puretone examples in table 4-1 to describe these.) What are their growth rates? What capabilities systems enable their success? This discussion brings to life your current level of coherence compared to that of your competitors. You may discover that even the most successful businesses in a sector are not fully coherent.

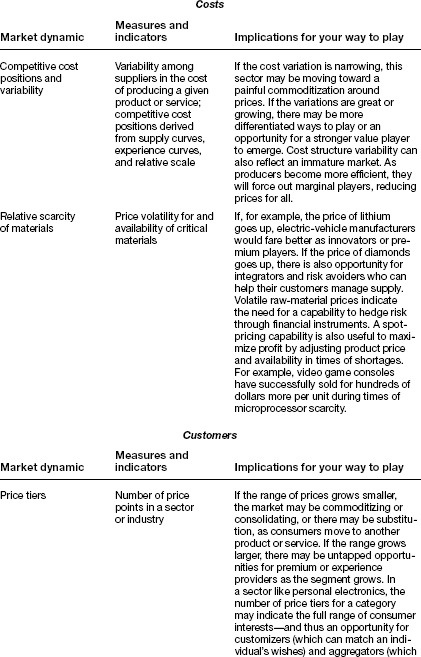

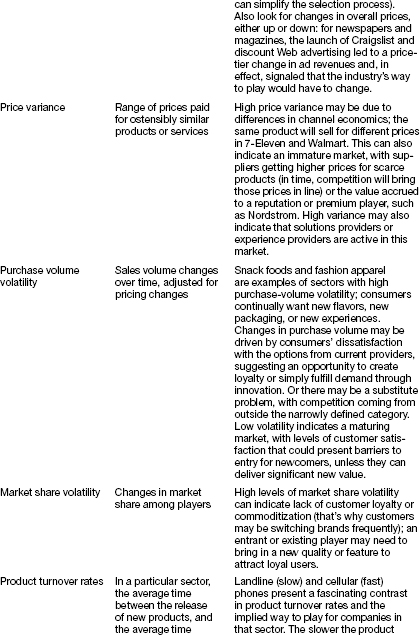

Market dynamics: Use some or all of the indicators in table 10-1 to develop hypotheses for new ways to play. Your goal is specific: to recognize potential ways to play that will be available in your market in the future. Look at trends and drivers, seeking a deeper understanding of how your market has behaved up until now, how it is changing, and if the current winners will keep winning. The various tests in this table explore the ways in which your customer base is growing or shrinking; your materials are getting more scarce (or more plentiful); your competitors are thriving or struggling; and so on. Pick the tests that seem likely to offer fresh insights about potential ways to play. In applying these tests, beware of jumping to conclusions that may limit the range of options you consider. In particular, avoid the temptation of trying to size the market for your products and services. At this early stage, sizing the market can bias you toward large populations and make it hard to see the value of other markets, which could turn out to be more viable and profitable for you.

Puretones: Look at the puretone ways to play, as listed in table 4-1. Walk down the list, considering each in turn, asking which resonate with the insights from your winners and losers and market dynamics discussions, or with your general sense of viable growth options. Then talk through the implications of each puretone. For example, if you wanted to be an experience provider, which customers would you try to reach? What would be the most compelling market? How would it be different from your current (implicit or explicit) way to play? As part of this exercise, you may also hit on a puretone that isn’t on the list or hasn’t been conceived yet. That’s fine; write down your description of it, for consideration among the other possible options.

Table 10-1

Market dynamics to consider when assessing your way to play

Opportunities for Growth

As a way to engage people and form more hypotheses, brainstorm a list of opportunities for growth. Include ideas you have considered in the past and new approaches; seek out ideas from people around the company. Look again at the market dynamics analyses in table 10-1: Do any of them suggest possible growth avenues?

For a more structured way to brainstorm about growth, look at the four growth types outlined in chapter 7 (see figure 7-1). Work your way outward from the center. Are there places where you can find added headroom for growth, with your existing lineup of products and services? Are there adjacencies to pursue—products or services close to yours, that would make use of your existing capabilities or capabilities system? Where are the most promising candidates for geographic expansion? What new platforms for growth could be built by transforming your business entirely? Cast your list of growth paths broadly at first. Then narrow it to those that seem most promising.

Capabilities-Forward Discovery

In this sub-step, look at possible ways to play from a “capabilities-forward” angle. Focus on the things your company does well, and derive hypotheses accordingly. This is a critical part of the process, because, for the first time, you are considering potential ways to play and capabilities in light of one another.

Conduct a capabilities inventory:What is your company known for doing exceptionally well? Conversely, what have your competitors been able to do that you can’t match? How are your capabilities changing? Are they improving or declining?

Scan the puretones (table 4-1) for ways to play that would logically make use of your most distinctive capabilities:You can also use a timeline-based discussion to look at your capabilities in more depth, and to get a sense of which ways to play could fit with your culture and identity (see the “Decision History” box).

Synthesis of Hypotheses

Inevitably, as you go through the discovery stage, hypotheses for ways to play will emerge. You will find yourselves testing them informally, thinking about which ones are feasible and what investments they would require. Now, in the final workshop, you bring all these insights together: combining your list of possibilities from the market dynamics exercise, your list of puretones, and your list of growth hypotheses, along with any others. Talk through them all, and settle on three to five way-to-play hypotheses to take to the next stage.

The process of synthesis is neither purely analytical nor intuitive. As William Duggan of Columbia Business School has observed, most creative synthesis involves drawing new links, in your mind, from what you observe now to what you know from experience. Trust that this type of insight will kick in as you discuss the hypotheses you have developed.1

Combine puretones into new hypotheses. Draw on what you’ve learned about your company and your market. Look for ways to play that resonate on all three dimensions: market-facing, geared toward growth, and relevant to your capabilities. But don’t limit yourself too much; follow your collective sense of the most effective hypotheses, rather than any checklist. For example, feel free to keep an extremely valuable way to play in the mix even if it’s not clear how it would fit with your capabilities. You will seek coherence more explicitly in the next stage.

The final ways to play that you select should differ enough from one another that a casual observer could easily distinguish them. For example, if you have two hypotheses for being a value player, combine them into one. Don’t worry too much about the details; they will be refined iteratively in the next stage. The hypotheses should also be compelling enough that you can make a powerful story out of each of them, and be applicable to your own business and market.

Give each of the working hypotheses a name and write up a description of them all—and how they fit with the market factors, growth opportunities, and capabilities you’ve considered. Then take it to the senior team for approval. In the next two stages—assessment and choice—the core team and senior team, along with others throughout the company, will invest a great deal of time and effort in clarifying, iterating, and refining this list so that it becomes easier to make a choice.

The Assessment Stage

This is the stage of due diligence: you dig deeper into the issues that were raised in the discovery stage and validate your hypotheses. Test them with an eye toward the amount of enterprise value they might create and their feasibility. To accomplish this, evaluate each hypothesis through four lenses: its fit with your capabilities system; the way it positions you against competitors (your right to win); its financial prospects; and the risks you would be undertaking by pursuing it. As the research and discussion continue, revise the descriptions of these hypotheses to reflect what you are learning, and discard those that are not feasible. These assessments, conducted by the core team, represent vital input for the choices that must be made in stage 3.

The five sub-steps of this stage are all conducted by the core team. This time, they must occur in sequence, with the insights from each informing the others. As you work through these forms of assessment, we recommend also conducting at least a dozen interviews: ideally, two for each functional area of the business and some with select trusted customers or supply partners. During these interviews, discuss the strategies you are considering, their potential in value creation, and the capabilities and assets needed to make them work. Ask whether, in light of their observations and experience, your company is equipped to deliver this way to play, and why.

Though a formal review by the executive team isn’t necessary (that will take place in stage 3), it’s important to have clear, regular lines of communication so that the CEO and other leading executives can monitor the way the hypotheses are developing and offer guidance. Indeed, some members of the executive team may want to join the core team for some of these sessions.

Assessing Your Capabilities System

For each leading hypothesis, articulate the capabilities system it would require, the relevant capabilities that you already have available to your company—including those you have in-house, can draw on through alliances or outsourcing, or could reasonably develop to a distinctive level—and the relevant capabilities that you don’t have, that you would have to build organically or acquire (or both) to make this way to play work.

For example, a solutions provider might need to be great at (1) product assembly close to customers, (2) forecasting component demand, (3) online retailing, and (4) responsive and flexible supply-chain management. An experience provider might bring to bear (1) an understanding of how people interact with the product, (2) consumer-centered technology and design innovation, (3) distinctive branding, and (4) expert management of the customer experience. And the mutually reinforcing capabilities for a value player might be (1) demand forecasting, (2) component selection and procurement, (3) lean and efficient supply-chain management, (4) management of relationships with retailers, and (5) expertise in understanding the features valued by customers.

Separate the distinctive capabilities that would be needed to make each way to play work from the table stakes. For the most critical capabilities, estimate the amount of investment that would be required to give your company the distinction it needs in that domain. If too many gaps need closing, then ask whether you can really change enough to deliver the capabilities to win with this way to play—and if the answer is no, discard that hypothesis. Conversely, the more advantaged your capabilities system compared with those of competitors, the more promising the option.

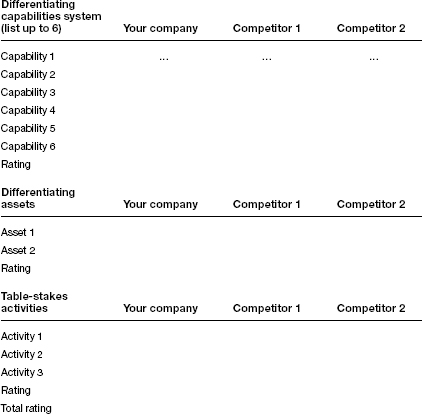

Assessing Your Right to Win

As you may recall from earlier chapters, the right to win is the confidence held by companies with more coherence than their competitors. In this substep, you look at every way-to-play hypothesis in light of your own relative coherence against that of your competitors. Which company brings the right combination of a capabilities system that the market wants and the assets that are needed to succeed?

The “right-to-win exercise” shown in table 10-2 can help you clarify this assessment. For each way-to-play hypothesis, create a separate table based on this worksheet. Assess your capabilities and assets alongside those of your main competitors (and for new markets, consider potential entrants).

Table 10-2

The right-to-win exercise

In this exercise, you assess your own company and those of your competitors on various capabilities, assets, and other activities. Rate them as above par, at par, or below par. (See explanation in the text of chapter 10.)

Although assets are not as sustainable as capabilities, we include them in this worksheet because they represent criteria that are important to the market. The worksheet also separates your distinctive capabilities (those which, as part of your capabilities system, enable your way to play) from table stakes. For instance, if you are a manufacturer, you may need some assets, such as facilities and patents. You will also need a table-stakes proficiency at distribution and logistics. These may not, however, represent the distinctive capabilities that set you apart from rivals. You don’t need to be above par on a table-stakes activity; you just want to be as proficient as the market demands. (Indeed, being above par on a table-stakes activity suggests you are overinvesting, which we have addressed in chapter 9.)

Rate yourself and your competitors (current or potential) for each element on your list: above par, at par, or below par. To keep track of the many elements in this discussion, use colors: green for above par, yellow for par, and red for below par. In developing these assessments, you will probably draw on interviews, analysis, and your own open, dispassionate discussions about your right to win, how plausible your assessment of it is, and how many gaps need to be addressed.

One analogue for this exercise is the analysis that Wharton School marketing professor George S. Day suggests for evaluating potential investment in new products. (He, too, advises teams to ask not just “Is the market real?” and “Is it worth doing?” but also “Can we win?”) It’s not easy to bring the necessary perspective to bear, to be dispassionate and honest. “A critical job,” says Day, “is preventing teams from regarding the [exercise] as an obstacle to be overcome or circumvented . . . It is a learning tool for revealing dubious assumptions and identifying problems and solutions.”2

Assessing Your Financial Prospects

In the discovery stage, you associated potential growth options with each way-to-play hypothesis. Now assess those growth options, as a group, to conduct a realistic estimate of the potential economic value. (In some companies, there might be sixty or more growth options on the table, each linked to one or more hypotheses.) How might these growth options affect revenues and profits? What would be the financial upside? How large might the potential market be, when sized in terms of revenue, profit, and impact on enterprise value? Where are the economies of scale? Use all of the traditional analyses that are credible in your business: market size, return on investment, enterprise value, and so on. Make sure to provide the rationale for your estimates so that others understand your thinking. Then, tally up your estimates to get a comparable view, for each way-to-play hypothesis, of its financial potential as a whole.

Assessing Potential Risk

Make a clear-eyed assessment of everything that could go wrong for each way-to-play hypothesis. What are the risks of reputational damage, legal liability, or financial loss? Could the risks hurt the profitability of your biggest and most successful current businesses? If the change you’re contemplating would require a major restructuring, do you clearly understand what this would entail, and do you have confidence in your ability to carry it off? Would your existing customers be hurt?

Every company, of course, needs to take risks to grow. The value of this exercise comes from establishing a clearer view of the trade-off between risk and reward for each way-to-play hypothesis. Ultimately, it will be up to the most senior executives to decide which overall rewards would be worth the risk. For that reason, once the risks have been initially identified, it is valuable to conduct a joint session with the core and executive teams, to determine which risks need further research and analysis before making a decision.

Deliberation and Presentation

By the end of stage 2, the members of your core team should be able to speak to the merits and risks of each way to play and its associated capabilities system. You should be confident that any of the hypotheses you present could become viable ways to play, worthy of strong consideration. There should be a logical rationale for each, showing that, if designed and executed well, it could lead to a right to win.

The Choice Stage

You’ve been at work for two months or more—perhaps several months. Your hypotheses have turned into full-scale options. You have in mind several ways to play. You are aware of the capabilities system that might be necessary for each way to play. You have thought about the products and services that would fit with these. Now it’s time for your top executives to review the assessments made in stage 2 and pick a strategy that is more coherent. In short, you now make a commitment to the sustainable future the company will create.

The choice of a way to play and capabilities system is not like most of the other business decisions that you make. It is a fundamental commitment to your objectives and targets, and the logic underlying them. This choice will become the basis of many priorities. It will determine the way you resolve many day-to-day conflicts. It will generate the essential advantage that your organization needs. It should not be treated as an ordinary decision.

As a result of this choice, some brands and services will almost certainly rise in importance, and people working in these businesses will gain a huge morale boost. Other product and service groups will face tougher times. Henceforth, they won’t have the same level of investment funneled toward them; some may be divested or shut down. Some major functional initiatives you had slated for next year may no longer be differentiating; they will be halted.

It is thus natural to feel a little exposed when making this choice. But if you have managed stages 1 and 2 effectively, you should have confidence in your decision. You are taking a fundamental leap of faith, but it is supported by your experience and the work you and your team have done.

Typically, this stage begins with the core team recommending an option. To get to that point, three exercises are relevant. In some companies, these sessions have been so valuable that they go on for two or more days—giving people a chance to sleep on the implications. Any of the three might serve your purpose:

• Strategic debate workshop: The case for adopting each way to play is advocated by a different member of the team, often drawing on the knowledge gained from his or her existing position. The head of finance might argue for becoming a consolidator, the head of marketing might advocate the reputation-player route, and the head of operations might speak for the fast-follower option. Each leader paints a picture of what that way to play would accomplish; the capabilities system that would be required for success; how it would offer differential value to customers; and how to fill the gaps in capabilities, assets, products, and services.

• Alternative futures: Different members of the core team present narratives for each prospective way to play, looking backward from five years in the future. What happened, as a result of taking this path? What challenges did your company face? What capabilities did you have to acquire or develop? Where did you see your greatest competition? With as much substantiation as possible, how successful did this path turn out to be, and why? Imagine a newspaper headline about your company, based on your pursuit of this way to play. Does it depict you as dominant in your industry, as a takeover target, or as somewhere in between?

• Stress tests: Look at the challenges and potential rewards for each alternative way to play. What challenges do you face around capital markets; environmental, safety, or health considerations; personnel and talent issues; global and local competition; and disruptive technologies? What is the plausible range of market share and profitability available under each way to play? Compare them all to see how they stand up against similar challenges.

However you design these workshops, the chief executive and the senior team should be present for the final iteration—because ultimately the decision rests with them. In this session (and any follow-up sessions that are needed), the senior team should settle on the following components of your company’s strategy:

• A chosen way to play and capabilities system, and a first take on the products and services that fit this “sweet spot.” (If it’s a large enterprise, you may choose to divide your company into separate clusters, each with its own way to play and capabilities system—but do so consciously, knowing that you will have to compensate for the incoherence that this split creates.)

• Preliminary options and directions for the ways in which you will create value—through growth, M&A, and reducing unnecessary costs—so that you can invest more heavily in the capabilities that matter.

• Criteria for judging your success. Some criteria may simply represent higher performance—an increase of ten points in market share, a doubling of revenue growth, or a specified level of cash flow. Others may reflect your chosen capabilities—the attraction of certain types of customers (for an experience player), turnover time for product launches (for an innovator), or margins compared with competitors (for a value player). These criteria are not meant to force results, but are meant to help build judgment about your progress.

• A general migration path to your chosen way to play. As part of this, the senior team needs to make an explicit commitment, both to the result and to the remaining time and effort that it will take to realize this strategy.

You have presumably gone through this exercise aware of the benefits of reaching one single way to play and capabilities system, with the coherence premium that provides. Nonetheless, at the broader enterprise level, there may be reasons one way to play is not pragmatic right now. Even if you choose just one, there may be a long migration path ahead of you. Remember, in either case, that in creating value, relative coherence is what matters. If you are planning to retain more than one way to play, talk openly about the tradeoffs. How will this affect your ability to invest in the capabilities that matter? How will it distract you? How can you gain the clarity you need against more focused competitors?

During the choice stage and in all subsequent stages, especially if you are the CEO or a senior leader, keep in mind that everything you say, do, and pay attention to will be closely watched—even more closely than usual. Others will expect you to hold to these commitments. If you are not visibly paying attention to the strategy you have chosen, no one else will, and for good reason: they would be making themselves vulnerable by embracing major changes that the top executives do not fully support. Conversely, if you do make a full commitment, then you establish a model for new behaviors throughout your company—the kind of behaviors you will need if the strategy is to work.

The Transformation Stage

A senior executive during this stage, surveying a wall-sized list of things that had to be done, turned to the rest of the team and said, “What do we do first? We can’t do it all right now.” One deliverable in this stage is a plan that answers that question: how you expect to build the capabilities you need, change your investment plans, design new organizational structures and practices, and adjust your portfolio—and in what order? The other deliverable is your initial actions: several highly visible moments of truth, which set in motion the necessary transformation that will allow you to realize your way to play. By the end of the transformation stage, your company will probably have shifted its hierarchy, recast goals and incentives, reallocated resources to the key capabilities, launched detailed plans to capture the primary growth avenues that were identified, and reprioritized R&D projects. These decisions will demonstrate to everyone that you are moving toward coherence.

You’re crossing a threshold into a new order that must be planned for and developed deliberately. Everything is still new. Perhaps that’s why this tends to be one of the most enjoyable parts of the process for the executives involved: a great moment when you roll out the choice, reorganize the company around it, and see a wide range of activity begin, all moving toward greater harmony.

At the same time, no matter how prepared you are, the transition is challenging. Others in the company are waiting to see if you blink. They want to know if they can follow your lead full-heartedly, without fear of wasting their efforts. They also want to know, as you reorganize, what will happen to their positions, projects, and prospects.

The development of plans might last several months and involve discussions at many levels. At the executive level, there will be many pressing questions to answer. How do you expect to preserve the value of parts of the company that won’t stay in the portfolio, and how can you get a good price for them? As you move your investments toward the capabilities that really matter, where will spending reductions be expected? What kind of knowledge must be codified to improve the capabilities in your system, and how will that be managed?

The core team, and others, may also get involved in organizational change plans. The process could include identifying and reaching out for the key champions, developing large-scale ways to help people model new behaviors, and assessing leadership capacity. Leaders in each region or business unit may need to talk through their ideas about value creation, growth, M&A, and cost-cutting. Given the choice of an overarching way to play and capabilities system, what changes should take place in these arenas? What new formal structures, informal networks, channels of communication, cultural change efforts, and forms of recruiting and talent management are needed? Some members of the core team may move into a facilitative role at this stage, working with people throughout the company to help them develop capabilities-driven strategies for their parts of the business.

The “moments of truth” will be decisions and actions that signal to everyone the magnitude and direction of the change. Several good examples are available from Jack Welch’s tenure as CEO of GE. Soon after he took office in 1981, he eliminated 80 percent of the strategic planning staff positions. During the next three years, he divested 117 business units, culminating in the sale of GE Housewares, its small appliance business, to Black & Decker in 1984. As Noel Tichy and Stratford Sherman put it, this was a failing business with little connection to GE’s capabilities or overall strategy, but it was an iconic enterprise for people in the company, because they could see their logo on alarm clocks and hair curlers in homes around the world. The sale of GE Housewares sparked a “process of self-discovery at GE, forcing unexamined issues into the open. For the first time in memory, employees throughout the company seriously began to ponder GE’s mission, questioning assumptions and discussing the unspoken.”3

Something similar may happen in your company as you create your own moments of truth: your first bold moves toward coherence. Expect to conduct lots of conversations and to encounter both overt and covert skepticism and resistance. One afternoon, you face your boss (or a board member) questioning why a profitable brand must be sold. The next morning, you kill several innovative projects over the cries of their champions. “Sorry, it doesn’t fit,” you have to say. Or, “We have more potential in this other way to play, which means we’re getting rid of some of the capabilities you were counting on.”

You can also count on sparking people’s enthusiasm and interest. Now that you’ve put your stake in the ground and it is clear to everyone where the company (or the division) is going, you will find many people climbing on board. They understand that they have a better future in a company that is coherent, and it is up to you now to execute that future with the same care and consideration that you put into determining it. The more you can get your valuable people engaged (including those whose projects were killed), the more effective the overall transformation stage will be.

The Evolution Stage

By the evolution stage, your company has entered its “new normal”: it is pursuing its new way to play, exercising its capabilities system, and experiencing the right to win firsthand. In this stage, you become a company that “lives coherence every day,” following through with the practices and relationships that enable the capabilities system that delivers your way to play. At the same time, the world is changing—sometimes discontinuously—around you. A variety of challenges will come up that cause you to apply your strategy in new ways. Thus you continue to make decisions that reinforce coherence and prevent you from slipping back into your earlier fragmented state.

Though the details of this stage will vary dramatically from one company to the next, one principle remains constant: make it a continuing priority to apply your capabilities system to the greatest number of products and services within your way to play.

The evolution stage is nonprogrammatic: it never ends. But in its own way, it is as dramatic and significant as any of the previous stages. It involves continually adapting, improving, and extending the innovations; movements toward growth; and other practices that allow you to apply the capabilities you need. From here on, you write your own rulebook, and it should be coauthored by everyone who is committed to being part of your company’s success.

In preparing for this journey, you need to consider two more topics: the changes needed in your organization (chapter 11), and the challenges of leadership (chapter 12).