CHAPTER FOUR

THE WAY TO PLAY

Since 1990, the largest retail chain in the world has been Walmart.1 It has more than 3,500 stores, more than three hundred product categories on its shelves, more than two million employees, and about one-third of the U.S. population visiting its stores each week. Dozens of books have been published about the chain, recounting the unique value proposition set forth by its founder, Sam Walton (“Save money, live better”) and its growth from a small-town Arkansas merchandiser to its immense scale and scope.

Most observers attribute the chain’s success to its impressive logistics operations, its ability to get vendors to fall in line, or its position as a low-cost retailer. But having one or two superior capabilities or a compelling strategy in itself is not enough. Many retailers have tried to market themselves to cost-conscious customers, with far more limited results. What really underlies Walmart’s competitive advantage is a coherent system that involves its strategy, capabilities, and offerings and that lowers the company’s total value-chain cost in a differentiated manner.

It starts with a precise and powerful way to play. Walmart is a big-box provider of everything from groceries to electronics to houseplants at “always low prices,” largely without special sales or discounts. It has, more or less without exception, stuck to this strategic approach since its founding in 1962. Its preferred customers have always been the same: price-sensitive shoppers and “brand aspirationals” (highly cost-conscious consumers who seek out brand-name products). You won’t find a Walmart store on Fifth Avenue in New York, the Champs-Elysées in Paris, or alongside Nordstrom, Saks Fifth Avenue, or Neiman-Marcus in an upscale shopping mall. That would not be consistent with Walmart’s chosen way of creating value in the market.

Over the years, Walmart has built and carefully honed a remarkable capabilities system to enable and support that way to play. First, it wrings maximum efficiency from its supply chain, integrating aggressive vendor management techniques, expert point-of-sale data analytics (its famous retail-link system), superior logistics, and rigorous working-capital management. Another capability is the unparalleled mastery of “location, location, location”: the selection and acquisition of real estate, especially in rural and suburban North America. Finally, Walmart has a sophisticated capability embedded in its retail conception and design, which it uses to craft an ambience of wholesome, no-frills friendliness (like that of Southwest Airlines) that makes its preferred customers feel welcome. These three capabilities work together to enable Walmart to outpace other retailers in getting the right product to the right store in the right quantity with remarkable efficiency.

Everything Walmart does is thus matched tightly to its preferred customers and hence to its way to play. The retailer does not sell big-ticket items like furniture or large appliances, where it could not have a meaningful cost advantage. Nor does it sell items such as music CDs with explicit lyrics that run counter to its customers’ values. It innovates constantly within its chosen constraints: opening mini-clinics in its stores or tailoring its product assortments to local consumption trends. Walmart product buyers can identify hundreds of traits to define the assortment for any given store; a sporting goods buyer, for example, might use “freshwater” to designate a Minneapolis store and “saltwater” for a store in Plymouth, Massachusetts. Walmart’s capabilities also allow it to feed vendors better information than they have themselves about customers; this increases the company’s leverage with suppliers and allows it to move inventory with extraordinary efficiency. Finally, while reaching out for new customers, Walmart also finds ingenious avenues for growth within its existing customer base and its ongoing way to play. (In chapter 7, we’ll describe Walmart’s renewed growth strategy in more detail.)2

Walmart’s most visible U.S. competitor, Target Stores, might seem at first glance to be aiming at the same general market segment, but Target has a different way to play. Target—often pronounced with a mock-French accent (“Tar-zhay”) by devotees—similarly seeks to save its customers money. But it also provides fashion-forward merchandise for image-conscious consumers. Everything from the store layout to its advertising to its inventory is intended to convey an eye for style. For example, the lack of piped music and the minimal use of public address announcements makes the store feel clean, spare, and frugally upscale.

Target’s way to play was developed through a thirty-year evolution within the Dayton Hudson department store chain (formerly known for its flagship Marshall Fields), which changed its name to the Target Corporation in 2000 and closed or sold its other brands soon thereafter. The capabilities system that supports this way to play includes image advertising, the management of urban locations (which Walmart generally does not have), and a distinctive approach to “mass prestige” sourcing, including the cultivation of exclusive partnerships with some of the world’s leading designers, such as Mossimo Giannulli and Michael Graves. To match the needs of its younger, more urban customer base, it sells furniture and more clothing than Walmart.

Another of Target’s important capabilities involves pricing. Target carefully monitors prices to ensure that on selected high-profile items, the kind that draw people into the store, it matches the prices of Walmart and other competitors. But in its other merchandise, Target moves “up the pricing ladder” more rapidly than Walmart, carrying an assortment of higher-priced, higher-value items that appeal to more affluent, fashion-conscious shoppers (and that provide the retailer with larger margins).3

Now consider Kmart, the last and least successful member of the U.S. big-discounter triad (coincidentally, all three retail chains launched operations in 1962). In and out of bankruptcy in the early 2000s, Kmart is still struggling to define its way to play in the mass-market retail space. It describes itself on its corporate Web site as a “mass merchandising company that offers customers quality products through a portfolio of exclusive brands and labels.”4 That could describe any retailer from Old Navy to The Home Depot.

As a Walmart customer, you know you’ll save money and still feel welcome. At Target, you know you’ll get fashionable products at prices that feel reasonable. What, then, is Kmart’s niche? Walk though a store, and you’ll discover designers like Martha Stewart and Jaclyn Smith in the low-budget ambience of a warehouse. Since its merger with Sears, Roebuck and Co. in 2005, Kmart has started carrying Kenmore appliances in its stores. This is a high-potential growth move, given the strength of the Kenmore brand, but it may require the high-touch expert sales assistance that many Sears customers expect.

In short, Kmart has not established an identifiable way to play—a way that reflects both its customers’ needs and its own capabilities. Harry Cunningham, the founder of Kmart, reportedly admitted that Sam Walton “not only copied our concepts, he strengthened them.”5 This lack of a clear concept about how to reach the market is probably the single most important factor in explaining why Kmart’s fortunes have fallen so far, compared with its two rivals.

Aspiration, Reality, and Choice

Every consistently successful company that we know has a clear understanding of what differentiates it as an enterprise: specifically, the way it creates value for the people who buy its products and services. This is their way to play in the market. A well-developed way to play is a chosen position in the market, grounded in a view of your own capabilities and where the market is going. It represents what Gary Hamel and C. K. Prahalad called “strategic intent”: a sense of direction that can prompt a group of people to stretch beyond their day-to-day goals or, as the authors put it, “the dream that energizes a company.”6 A way to play is both realistic and aspirational. It recognizes the achievements and limits of the past, is oriented toward what you hope and expect to do in the future, and gives you a clear rationale for the choices you will make between now and then.

Developing a way to play is not a casual undertaking or an academic exercise. It is the pivotal moment in a capabilities-driven strategy (as described in chapter 10). You will live by this choice and develop it for years, and maybe forever. A way to play is both “capabilities-forward” and “market-back”; to develop it, you look outward, with acute analysis and observation of your industry (and how it is changing), your customers, and your competition. You also look inward, at the capabilities you can build and the limits on that potential; you should not take on a way to play that you can’t possibly master. Above all, you identify and codify what is distinctive about you now, and how you hope to be distinctive in the future. In most cases, you are far better off understanding what you do well and looking for the markets that will respond than you are looking for attractive markets and trying to design a way to play to reach them, no matter what it may take to deliver.

We are sometimes asked if there is a danger of a company’s picking the wrong way to play—a strategy that is not right for its market. Certainly, it’s possible, but a much more common problem is not to pick a way to play at all. Many companies just respond opportunistically to what they think their various customers demand. They then keep shifting as demands change: lowering prices, making heroic efforts to meet a short-term need, or expanding to new “adjacent” segments. Other companies maintain a complex array of products and services that makes seeing through to any one way to play impossible. This does not create value; such companies tend to eke out growth and profit numbers by endless cost cuts and typically cannot sustain performance, particularly when a more coherent competitor appears.

If your process for defining a way to play is rigorous enough and you know your business sufficiently well, you are likely to see a way to create value. Your ability to capture that value depends on whether you can act sooner, faster, and more effectively than your competition. The goal of a capabilities-driven strategy is to help you hone your judgment about your way to play, to make a choice, and to put it into action.

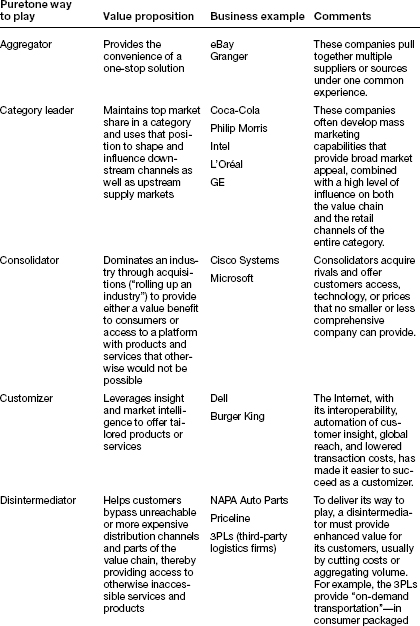

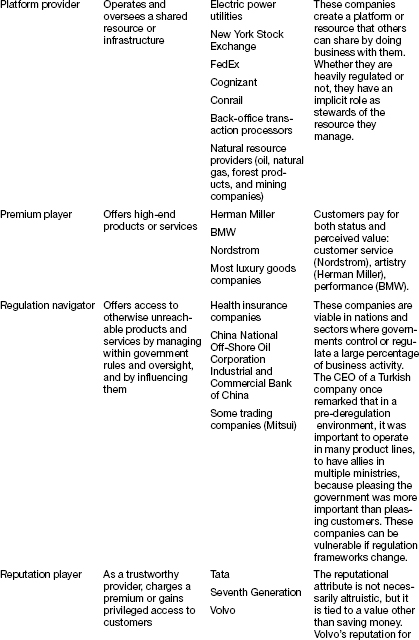

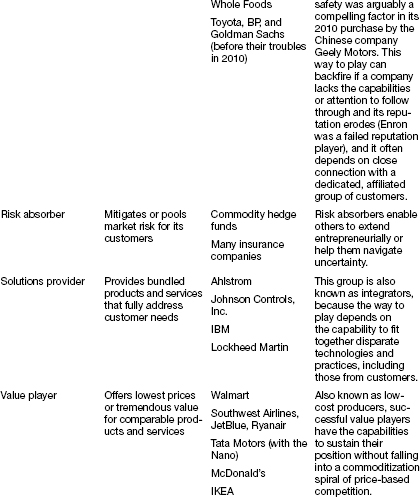

Puretone Ways to Play

You can generally start thinking about your company’s way to play by looking at common, generic ways of creating value. These are what we call puretone ways to play. They may not fully capture your business. But when you mix a few puretone ways to play in a well-defined way, like mixing primary colors, you might end up with a more precise hue that reflects your company’s best strategy. In some sectors, you might stay fairly close to a puretone; for example, you could be a value player. But in most cases, you will end up crafting your own distinctive way to play, with puretones as a starting point.

Table 4-1 shows the puretones we work with most frequently. Most of them are commonly observed in the business literature; for example, at least six major books have been published on the “experience provider” way to play.7 This list is illustrated with business examples that are evocative but not always a complete description of the company. For instance, McDonald’s is a longstanding experience provider—as well as a textbook example of a value player. So we included it as an example of both puretones.

Table 4-1

Puretone ways to play

In real life, very few companies have only one puretone way to play. Most successful ways to play are combinations or refinements of several puretones, although sometimes they have a major “hue.” For example, IKEA, the global leader in home furnishings design and retail, is primarily a value player; its way to play is evident in its slogan: “affordable solutions for better living.” But this Swedish company, which designs and sells its wares for a broad global consumer market, has also established itself as an innovator (for example, it designs its own furniture and creates its own distinctive paints, lacquers, and finishes), and, to some extent, as an experience provider—its distinctive store layout, play areas with free pagers for parents, and Swedish-style in-store restaurants make people want to spend time in its stores.

Looking at puretones can help you see the differentiation in an industry. In many sectors, corporate ways to play have shaped the market as they evolved, allowing two or more players in the industry to sustain profitable businesses in very different ways. Consider, for example, the personal computer manufacturing industry—where companies have carved out identities according to different combinations of puretones.

Acer: Founded in Taiwan in 1973, Acer is a value player, but it has resisted commoditization by also being a fast follower and a consolidator. Over the years, Acer has bought dozens of computer businesses, including Gateway, Packard-Bell, and the personal computer division of Texas Instruments. Acer is also a particular type of aggregator, acting as a gatekeeper to Asian innovation and low-cost manufacturing, packaging the “Wild East” technology in more accessible form. The company buys massive quantities of parts—such as processors, hard drives, and video cards—and assembles them into personal computers that can’t be beat on price. To match consumer needs, Acer depends on insight from big-box retailers about what consumers will pay for different configurations.

Apple: This company’s way to play combines being an innovator, an experience provider, and a premium player. Apple makes devices that intuitively fit with the way people work, play, and learn, and it provides the complexity of a full-featured computer or media environment with the simplicity of an appliance and a high level of technological control. Apple’s way to play dates back to the early 1980s, when the company pioneered the first commercialized graphical user interface. It famously bears the mark of longtime CEO Steve Jobs, who leads the company as an impresario might lead a theatrical group. The same way to play applies in all the sectors where the company does business—hardware, software, telephones, portable devices, the online iTunes service, and the Apple retail stores—which few observers thought would succeed when the first one opened in McLean, Virginia, in 2001.8 Some capabilities, such as manufacturing, are table stakes; these are consequently deemphasized and outsourced. The difficulty and distinction of Apple’s way to play is obvious: no other company has chosen it. For years, the company was considered marginal in the personal computer industry, with a relatively small market share; only in the 2000s did it gain enterprise value commensurate with its influence on innovation.

Dell: This consummate customizer, value player, and aggregator has been positioned for years as the leader of the direct-sales model, which distinguishes it from Acer and other value players like Lenovo. Dell offers computers with leading-edge technology—assembled from a broad group of suppliers, sold directly over the Web or the phone, tailored to individual needs, and made available quickly and reliably. This traditionally gave Dell a 15 percent cost advantage: because customers paid only for the components they wanted and avoided the expenses of computer stores, they paid a lower price than did purchasers of prebuilt systems. In 2007, as the company navigated some product quality and service challenges, Michael Dell returned as CEO. Dell now faces the challenge that, as hardware costs have fallen, the value of customization may not be as significant.

Hewlett-Packard: Once known as an innovator, Hewlett-Packard has developed a way to play that is closer to a consolidator and a solutions provider. It spent $25 billion on acquisitions between 2000 and 2010, buying Compaq, Electronic Data Systems Corporation (EDS), Mercury Interactive, 3Com (known for inventing the Internet protocol), Palm Computing, and many smaller software companies. In recent years, HP has pulled these together with its own engineers to provide end-to-end, Web-based computer services for businesses and individual customers. The company draws on open systems and platforms, delivering a high level of convenience and accessibility—starting with a Web site that features courses and services like Web site design as prominently as it features laptops and printers. HP competes increasingly with other large systems providers, such as Cisco and IBM. Its printers, calculators, and other devices continue to sell, but they are increasingly marketed as part of an integrated system in which customers, as well as employees, sign up for the famous “HP Way” and expect to be taken care of.

Although to a casual observer these manufacturers may seem to compete against one another, they have carved out very different approaches to the personal computer market, and they attract different customers accordingly. Their ways to play are distinctive, highly relevant to particular groups of customers, and closely tied to their company’s roots. Apple has a renowned and distinctive approach to design, but it could not do what Acer, with its roots near low-cost China, does. HP’s heritage in instruments and integration has similarly given it an edge in delivering innovative services (no matter whether it developed or acquired them). Dell’s origins in founder Michael Dell’s dormitory room, where he built computers to order for customers, led directly to its advanced supply-chain management and customization capabilities.

Now imagine starting a personal computer business. Your first strategic priority would be to find a way to play that was not covered by the companies described here. Similarly, if you were to open a new retail chain in the United States, you would look for a distinctive way to play and a corresponding capabilities system, neither of which could overlap those of Walmart or Target. You would probably not try to beat the computer makers or the retailers at their own games (unless you saw a weakness in their capabilities systems). Your success would depend on finding a game that you could play better than anybody else.

Building a Better Way to Play

How, then, do you get from a list of puretones to a way to play that will carry your company forward? In forming hypotheses and conducting in-depth reviews and workshops, you are looking for the critical insight: the spark of recognition that represents your company’s particular contribution to value.

We’ve already described that spark of recognition at Pfizer Consumer Healthcare (claims-based marketing, in chapter 1) and JCI (becoming the most expert designer and manufacturer of auto seats, in chapter 3). A more recent case occurred in 2010, when the executive team of a large food manufacturer decided to seek its own sweet spot. The executives saw an opportunity to build a major new business in prepackaged convenience food, and they started with three puretones that summed up three ways to do it:

Category leader: The company would become the most visible brand for its leading products, shaping the most important categories by increasing market share. To accomplish this, it would focus resources where it truly understood customer needs, and where it could build a better value proposition than its competitors.

Innovator: The company would rapidly develop and launch new types of packaged foods, taking into account trends and customer interest, and thus become the company known for leading-edge nutrition and convenience.

Solutions provider: It would give people “the meals they asked for”: providing prepared foods that could be easily combined by busy working families into customized ready-to-serve meals, while visibly seeking out consumer requests for healthier foods and responding with new offerings.

As they explored the external market in depth, the executives realized that there was an attractive market for each of these approaches—large and incompletely served by the current food industry. If they took on any of the three, they could profitably gain market share and solidify their brand identity in unprecedented ways. All three had roughly the same potential for increasing enterprise value. But the lightbulbs went on for the executive team only when the functional leaders began talking about the capabilities each approach would require.

“These are three different sets of investments,” said the manufacturing leader, “and we can’t do them all.” He went on to explain the differences in supply-chain management for each way to play. As a category leader, the company would need to cut costs and seek economies of scale while raising its manufacturing prowess: investing in process technologies and executional effectiveness. Becoming an innovator would mean configuring a flexible value chain that could launch new products rapidly and economically. The solutions-provider approach would mean a different type of flexibility: providing more packaged food sold at different temperatures—some frozen, some fresh. It would also mean building a more direct, collaborative relationship between operations and R&D.

The head of marketing and sales said she could see similar differences: “The merchandising forces would have almost no overlap.” As a category leader, the company would seek to own the shelf (or the sector) through sharp-pencil tactics (tightly tailored to each brand and local region) for pricing, promotion, and merchandising. The innovator way to play would emphasize another type of advertising and promotion: communicating the new consumer value propositions while ensuring rapid, widespread retail distribution of new products. Being a solutions provider would move the company directly into engagement with consumers, through online Web sites and other social media, displays for the store perimeters, and a great deal of marketing experimentation.

Suddenly, this was no longer a conversation about the market and its demands. It was a conversation about the company’s own capabilities and how the executive team might marshal those capabilities together. Where did the company really have strengths? Which trade-offs were the team members willing to make? Around they went, working through the discovery and assessment stages of the capabilities-driven strategy that we described in chapter 3, focusing their attention not just on the capabilities they had, but on those they were willing and able to build. Originally, they had expected to adopt the innovator way to play because it meant a higher-margin business. But after several meetings spread over the course of three weeks, they decided they had a better chance of gaining the expected amount of enterprise value as the category leader, because that fit the capabilities system that they already had. This decision has, so far, begun to pay off for them.

These types of insights don’t stem from a recipe book; there is no analytical formula for reaching them. But by starting with puretones and looking at their ramifications, you can draw on your team’s business acumen without being held back by old preconceptions. Just as Apple is not a pure innovator, HP is not a pure consolidator, and IKEA is not a pure value player, you must refine these puretones into more precise articulations of your company’s potential future.

Criteria for Judging Effectiveness

If your way to play successfully addresses the market, the potential for differentiation, the dynamics of your industry, and the feasibility of the approach, then it has a very good chance of success. Evaluate your proposed strategy using this checklist.

There is a market that will value your way to play

In other words, there is a sufficient number of chosen customers who will find your way to play meaningful. In determining the potential value in a market, we (like Michael Porter, Ted Levitt, and many others) recommend looking at the needs of customers, not at the way your production category is conventionally defined. Pay attention to “substitutes”: unexpected products that perform similar functions in different ways.9 If you produce customer-relationship management software and sales have dropped off, chances are your customers are spending not on a rival software package, but on Internet-based “cloud computing” services and analytics. If you make frozen foods, and a father isn’t buying your dinosaur-shaped chicken nuggets in the frozen-foods aisle, he may be buying the (nonfrozen) Organic Meals for Tots or taking his kids to a restaurant. If you’re a steel supplier, and a vehicle maker switches from you to another source, it may be to composites (engineered materials such as fiberglass or carbon fiber). A high number of substitutes in any sector may indicate that you haven’t yet found the right way to play or that you have more room for growth. In table 10-1 (chapter 10), we show a variety of tests for assessing the potential markets for your way to play.

Your way to play is differentiated from your competitors’ ways to play

In chapter 10, we’ll look more closely at ways to analyze yourself and your competitors to see whether your way to play (along with your capabilities system and lineup of products and services) gives you the right to win. For the moment, it is enough to recognize the way in which your proposed way to play would compete with others. Having the same way to play as your competitors can work out advantageously if you have a better capabilities system, but in many cases it’s better to differentiate. Like the computer companies described earlier in this chapter, have you developed a distinct way to play that your competitors can’t emulate?

Your way to play will be relevant, given the changes that might take place in your industry

If you’re in a rapidly evolving industry, then your way to play should be tested against the external changes you see ahead. They don’t have to be certain, but if they are plausible and would affect your business, you need to take them into account. To test your way to play in light of external changes, engage in deliberate conversation about the dangers and risks of the changing industry, as well as the opportunities, and how you would respond. To be sure, as Clayton Christensen has pointed out, the ingrained capabilities that made you effective in the past—especially those that support your existing way to play—can make it difficult to change in the future.10 But the more clearly you understand how you add value, the more likely you are to see a discontinuity coming—and to be able to adapt to it effectively.

Some companies have deliberately tried to cultivate their ability to see discontinuities—so that, when their industry is ready to change, they have the time and awareness they need to look for growth outside their existing businesses. For these companies, paying attention to potential discontinuities is not a one-time event, but an endeavor that requires sustained organizational focus. In 2007, for instance, the CEO of MasterCard, Bob Selander, recognized that a range of disruptive forces could change the game for a company that had held its initial public offering of stock just the year before, and had flourished since then. These potential disruptions included the replacement of credit and debit cards by mobile phones and other electronic devices; possible major changes in regulation; and consolidation in the financial sector. Selander and his team developed a discipline of “dynamic strategy” that continuously engaged the whole organization in scanning the landscape, updating its views of market scenarios and their likelihood, and evaluating whether the time was ripe yet to consider developing a new way to play.

The defense industry in the United States provides another example of how external changes can prompt changes in your way to play while opening up the market to non-traditional competitors. Before 1990, most defense companies were essentially a combination of solution providers and regulation navigators. They were oriented around the Department of Defense’s demand for enormously expensive and capable weapons systems targeted at major threats such as the Soviet Union. Then the Berlin Wall fell. Defense acquisitions budgets were cut 50 percent in search of a “peace dividend,” and exotic weapons, such as stealth-bomber aircraft and nuclear submarines, were requested in much smaller numbers than had been originally planned. This shift was reinforced by the Al-Qaeda attack on September 11, 2001; massive weapons were of little use against terrorists and insurgencies hiding in caves and deploying improvised explosive devices.

The legacy defense industry had difficulty at first adjusting to the new realities, and non-traditional suppliers filled the gap. For example, U.S. defense-related agencies broadened their procurement strategies to include some overseas producers who already had the right to win for this new market. For example, just about every helicopter purchased since 9/11 by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (including the U.S. Coast Guard) was built outside the United States, and the U.S. Navy’s Littoral surface combat ships were produced in shipyards owned by non-U.S. companies.

At the same time, disruptive weapons technologies began to appear: robots, autonomous systems like the Predator and Global Hawk drones, and the global information grid, which transferred computer intelligence from individual ships, planes, and tanks to the network. All of this value shifted from producers of traditional military hardware to newly arisen network integrators. For example, the Predator drones that hunt insurgents in Afghanistan are guided remotely by pilots sitting in Nevada, and the real-time data these drones collect are analyzed simultaneously in multiple locations in the United States and elsewhere around the world. A new group of defense companies—some with roots in Silicon Valley or the computer industry, and some from outside the United States—sprang up to create and design these technologies. These companies had faster business cycles, new types of product-development strategies for this industry, and a greater willingness to experiment with untested concepts.

With their legacy business facing flat or declining revenues, the established defense companies thus face a challenge. They have to find a way to play that allows them to cut costs on existing projects—with more off-the-shelf commercial components, simpler designs, and more emphasis on everyday use. For example, the Electric Boat Corporation, which is part of General Dynamics, reduced the cost of building a Virginia-class nuclear submarine by half a billion dollars by ripping out unneeded complexity in the design and production.

The non-traditional suppliers also face challenging limits as the Department of Defense continues to refine its priorities. For example, the disruptive suppliers of robots and networking equipment have enjoyed a defense boom, but none of them have yet risen above $1 billion in sales, far below the $20 billion-plus volume of the legacy players.

All of the competitors are looking for ways to embrace the new technologies and business realities—without falling prey to the incoherence that would come from managing two ways to play, the old and the new, at once. Some are meeting this challenge through a concept called tailored business streams, in which they act as a systems integrator: pulling together outside technologies and proprietary in-house expertise in real time, to customize weapons systems for a variety of government clients.

Companies leading the way include Oshkosh Truck (a military vehicle manufacturer), Eurocopter (a French/German helicopter producer), and Cisco Systems (in its network equipment business). Some legacy producers are also entering this space through acquisition: for example, Northrop Grumman purchased Teledyne Ryan, the builder of Global Hawk drones. The most astute large incumbents have been careful to not overwhelm their new subsidiaries with incoherent legacy business models. The subsidiaries exist in the short term as discrete businesses, each with a separate way to play and capabilities system, until they can be integrated into the larger company. The companies that are first to master this approach, consolidating their capabilities into a single way to play, will shape the direction of the defense business for years to come.

Your way to play is supported by your capabilities system—and is therefore feasible

The most important criterion for a way to play has to do with your ability to deliver. How well does your capabilities system support this way to play? Rather than picking a market because it is attractive and developing the capabilities to match, pick the market where your capabilities will work. As with Walmart, Target, Apple, and the leading defense companies mentioned in this chapter, it won’t be enough to merely have relevant capabilities. They will have to be distinctive, well realized, sophisticated, and backed up by a deep organizational commitment, if your way to play is to be feasible in the real world. We will discuss this important topic of successful capabilities systems in the next chapter.