CHAPTER THREE

THE CAPABILITIES-DRIVEN STRATEGY

Our description of coherence—having an aligned way to play, a capabilities system, and a lineup of products and services—is a final destination on a journey that could take years for most companies to achieve under normal business conditions. The capabilities-driven strategy provides a guide for accelerating your progress on this journey.

Like all broad initiatives, this process starts at the top, with the close involvement of the chief executive of the business (and, if applicable, the board). Because of the importance of execution, it will move into the rest of the organization as well. Each of the thousands of decisions made daily in your company can take you a little closer to coherence, or a little further away. Only by generating broad awareness of your way to play and engendering better use of your capabilities can you build an essential advantage for your company.

To accomplish this, you will be working across multiple dimensions of your complex organization at once. You’ll look freshly at your situation and, in a strategic application of the scientific method, form and test hypotheses for your strategic direction before making a choice and committing your organization wholeheartedly to one of them. You’ll develop strategies for growth, cost-cutting, and M&A—all reinforcing instead of contradicting each other. You’ll move step by step, with each step increasing your ability to take the next. Within a few months, you’ll do what only a few companies have managed to accomplish over the years: make a definitive choice about how you will deliver what your customers need, and in the process transform your company.

How a Company Reinvented Itself

In the mid-1990s, Johnson Controls, Inc. (JCI), an automobile components maker based in Milwaukee, conducted exactly this kind of exercise. JCI consisted of four principal businesses at the time. One made building controls such as thermostats (a device that the company’s founder, Warren S. Johnson, had invented); another made plastic bottles; and a third made automotive batteries. The fourth, acquired in 1985, was Hoover Universal, a small company that made seats for motor vehicles. Renamed the Automotive Systems Group (ASG), it had enjoyed rapid growth under JCI; within ten years, it was making seats for eight million automobiles per year.

The existing way to play for this seat-components group was being a low-cost supplier (also known as a “value player”): snapping up market share by submitting the winning bids for seat programs designed by the major car manufacturers. JCI’s added value in seats was the efficiency and speed of its manufacturing and delivery, which were exceptional; and it also had a relatively short-lived advantage in a labor pool that was lower-cost than that of the vehicle manufacturers. JCI was also one of the most advanced just-in-time suppliers, having developed the operational discipline to assemble and ship car and truck seats in sequence, so that the seats could be unloaded without sorting, to match them to the trim coats, colors, and other requirements of each car as it rolled along an assembly line.1 This capability, among other things, had allowed JCI to acquire Toyota as a customer, which then enabled JCI to learn the world-class Toyota production system and develop its own prowess further.

But in 1994, the JCI management team looked more broadly at its business—and realized that the car-seat market was changing, creating new opportunities as well as imposing new forms of risk. Car makers in Detroit and Japan were starting to outsource more than just parts and components; they now increasingly looked to suppliers like JCI to provide full vehicle subsystems. Instead of delivering build-to-print specifications, an automaker would stipulate the weight, dimensions, and other criteria of a new vehicle platform and allow “Tier 1” suppliers like JCI to assume greater responsibility for the design of the seat systems and the performance of those designs.

This was such a different approach that JCI’s car-seat business leaders set aside much of the next six months to discover its implications for their business. While the degree of de-integration varied by automaker and geography, the trend was clearly gaining momentum. Based on these shifting market dynamics, JCI’s leaders identified four different ways to play in automotive seat systems. In order of increasing roles and responsibilities (and increasing levels of risk), they were:

• Component supplier: JCI could prototype and test the seats that car makers designed, using just-in-time, process control, and rapid-response capabilities to keep attracting customers.

• Systems assembler: JCI could deliver seats to detailed specs, producing and testing whole seat systems, building up its just-in-time and capacity planning capabilities, certifying suppliers, and developing a reputation for zero defects.

• System integrator: JCI could define the interfaces among seat components, integrate processes and designs with subsuppliers, develop new technologies, and build on its strategic sourcing and integrated delivery capabilities.

• Solutions provider: JCI could “design to concept”: suggesting alternative designs based on market needs, proactively developing product innovations, and assuming the performance risks itself (by taking on product warranty liabilities).

Rather than leap to a choice, JCI’s executives assessed these options and the capabilities required to succeed with each of them. Then they chose: They decided that they could add significant value by moving up the value chain to seat solutions provider, assuming higher levels of responsibility for end-user satisfaction and day-to-day problem-solving. This would be their optimal way to play. By getting involved earlier in the design process across multiple vehicle platforms, JCI could make good use of its expertise, economies of scale, and superior understanding of what automakers sometimes called “the golden butt”: what consumers wanted most in a car seat.

Was being a solutions provider the only way to play in automotive seat systems? No. Indeed, JCI’s primary competitors, Magna International and Lear, continued competing as system assemblers and integrators and remain in the business with those ways to play.

To be successful in its chosen way to play, JCI would have to build a system around a handful of mission-critical capabilities:

• Customer management: applying a consultative approach to selling valuable solutions, at the right prices

• Early-stage engineering and design: delivering technologically advanced products at low cost, and designing new innovations proactively, without waiting for guidance or specs from its customers

• Shelf technology: a critical capability that JCI hadn’t developed before: reusing designs from one program to the next, thereby gaining scale and scope in product development

• Integrated, just-in-time delivery: optimizing JCI’s existing lean manufacturing capabilities and network economics

• Extended enterprise: strategically exploiting vertical integration and maximizing the value of JCI’s partnerships with its own smaller “Tier 2” subsuppliers

These capabilities were all important in isolation, but they became truly formidable as a group. To compete successfully as a solutions provider, JCI needed to excel in customer management and first-time engineering and design. To make a profit doing so, it needed to develop the strong shelf-technology capability, enabling it to reuse designs. To execute, it needed to sustain its existing leadership positions in integrated just-in-time delivery and extended supplier relationships. Seeing how these were interconnected led to a moment of realization: JCI was better suited to car-seat design than any of its customers. GM, Chrysler, and Toyota had expertise only about their own seats. But the JCI engineers were specialists; they saw more seats than anyone else. If they kept developing and deploying their five capabilities together, they could gain a Michael Phelps–like advantage in the competitive arena.

The JCI team also knew the extent to which their company would have to transform itself to make this new strategy work. A year or two before, the company had opened a car-seat design and engineering center, with the idea of investing more heavily in innovation. That initiative had failed to yield profitable results, and in retrospect, one reason was clear: JCI had a long-standing tradition of de novo R&D; it created all-new seat designs from scratch for each new car platform. The cost would have been far less had ideas and technological solutions been applied from one car seat to the next. Now, engineers would finally have to give up their de novo approach.

The company would also have to decide which parts of the car seat to manufacture itself and which to outsource. For example, the senior team debated at length about the seat mechanism—the motor-and-switch combination that determines how a seat will move and tilt. Was it the specs (which JCI could hand off to a supplier) or the shaping of the metal and machine that differentiated the mechanism? In the end, the company decided to keep mechanisms in-house and continued refining them as part of its product portfolio.

When it came time to put its strategy into action, JCI followed through. Even though some of these decisions represented a break from its past, JCI’s leaders maintained their commitment to being a whole-solutions provider, and the company evolved accordingly.

The results were outstanding in share price and profitability. JCI’s market and management reputation soared, enabling the company to move from car seats to the design of auto interiors, a terrific move because it relied on the same capabilities system. To accomplish this, JCI purchased Prince, one of the most respected auto interior design firms, in 1996. Earnings growth over time was consistent and strong, and JCI successfully established an enduring essential advantage in the automotive interiors market.

A Process for Making Choices

JCI’s story represents a good example of a capabilities-driven strategy. It shows how a challenge can lead to a new aspiration: aiming toward a new goal that represents a desired pathway forward, rather than simply a reaction or retrenchment. Because you can’t design a way to play, a capabilities system, and a product and service portfolio in isolation, you must approach the journey to coherence as JCI did:

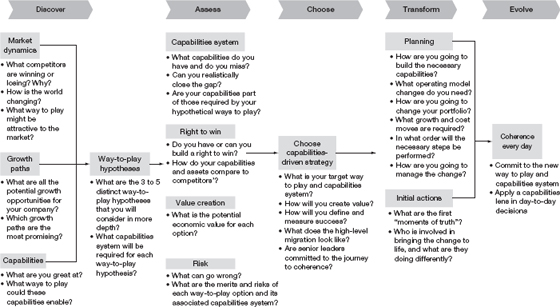

• You discover your choices. Through investigation and analysis, you come to a clearer understanding of your markets (including your customers and competition), your potential growth paths, and your capabilities. Rather than leap to a rapid decision, you develop hypotheses: credible options for a new way to play for your company.

• You assess each way to play in depth.Which hypotheses could give you the right to win in the market? And what would it take—in terms of capabilities —for each to succeed? What are the financial prospects, and the risks involved? One or more of these hypotheses will become the basis for the strategic direction of your organization.

• You choose a direction, a single way to play, and one capabilities system as the basis of your ongoing strategy.This is a significant exercise for the executive team and the major stakeholders of the organization and often includes the board. In choosing this direction, you set in motion a new way of doing business; you must therefore commit to it wholeheartedly.

• You set out to transform the company. You engage the rest of the company’s leaders in tough decisions about where to channel your next wave of investment. You design and communicate the implementation steps and portfolio moves needed to build or deploy the necessary capabilities and to reinforce and execute the new direction of the business. You take your first actions toward coherence, divesting parts of the business and reshaping others, sparking “moments of truth” that raise general awareness of the changes that are coming.

• You enable your company to evolve into the kind of organization that can stay coherent over time. You continue to engage the commitment of people at every level and develop the practices and relationships that will foster this strategy on the ground.

Figure 3-1 shows the overall process in schematic form. Though the details can vary from one company to the next, there are always several critical features. In the first three stages, you make a choice: Discovery leads to several hypotheses about your way to play, which you then assess and narrow down, preparing for the moment, when, like the JCI leaders, you define your distinctive potential. Then, in the last two stages, you enable the choice (transformation) and live the choice (evolution).

You can see that the process involves intensive give-and-take between different groups—a core team of carefully selected project leaders, the top team of senior management, and the rest of the staff throughout the enterprise. We’ll discuss this process and its stages in more detail in chapter 10.

This process can occur at the level of a significant business (like JCI’s seats business); it can also take place at the enterprise level of a larger, multibusiness company. In either case, the basic sequence is roughly the same (although, as we’ll see in chapter 10, there are some special considerations for the enterprise level).

Overcoming the Incentives for Incoherence

Once you make a choice and commit to it, you will set in motion a movement toward coherence, raising your most effective businesses, brands, and services in importance. There may be painful outcomes as well. For instance, the four big initiatives you had slated for next year may no longer make sense, given the capabilities you are now focused on. You may need to step in to halt them, along with other investments that are under way.

The tendency to relapse will be strong, and it’s important to understand where the incentives for incoherence come from. Some of them have to do with your history. Most companies of any size are complex. They evolved in messy and incoherent ways, dealing with ever-changing and inconsistent business environments as well as their own internal idiosyncrasies. The legacy of that evolution is a host of programs, processes, and imperatives, each with its own constituents. Many people have come to think of these incoherent practices as simply, “the way we do things around here,” a habit that has become etched into their neural pathways.2

FIGURE 3-1

Overview of a capabilities-driven strategy

Source: Strategy&.

Efforts to improve customer insight, for example, seem natural and laudatory—but they can lead a business unit leader at your company to propose bringing out a product line extension (“Consumers are asking for it”) without considering how it fits with your capabilities system. A benchmarking exercise might lead a functional leader to argue for new investment in distribution networks, because “our competitors have them” or “we must be great at this”—without recognizing that your existing distribution network, while it may not be the best, is more than adequate for your way to play, and the investment is better made elsewhere. Fear of getting left behind might lead another executive to say, “Our customers are going to digital media, and we have to figure out the new marketing model,” in a business where digital media is not a primary driver of demand. The need to size the potential customer base for a new offering might result in optimistic estimates that aren’t really applicable, because your company’s way to play will not succeed in that market.

Some incentives of incoherence—or, more accurately, disincentives to fight incoherence—can come directly from external stakeholders: regulators, suppliers, customers, and particularly Wall Street. To be sure, in the long run, capital markets channel their investment to more coherent companies. But in the short run, companies can often get higher valuations by making incoherent moves, like across-the-board cost cuts, that temporarily boost earnings. If you have been playing that game, your stock price may improve in the short term, only to decline over time. Conversely, outside stakeholders may object if you decide to divest some businesses that are highly profitable, but that do not fit your way to play or use the same capabilities. These stakeholders may not recognize the way they are distracting the rest of your business.

You may be tempted itself by opportunities that—while they don’t fit your capabilities system or way to play—seem like “sure bet” or “must-do” options for expanding into new geographies, products, or services. Some of these unnecessary activities might represent a hedge against the possibility that other things you try will fail. During good economic times, you may underestimate the risks of incoherence in these growth moves, because you don’t feel the penalty; its effects are masked by the general upswing.

These types of moves feel right, in part, because they historically conferred advantage. The first company to offer a new product or gain a particular asset had transient, first-mover advantage. The company with the greatest market share had economies of scale; indeed, this became part of the justification for growth, as companies vied to take advantage of scale in their back-office operations, customer reach efforts, and distribution channels. Similarly, the company that paid the closest attention to its customers, through methods such as market research and segmentation, could best offer them what they were looking for.

But the advantages of scale, and even of first-mover advantage, have diminished in recent years. Technology, cheap information, and outsourcing have conspired to lower the barriers to entry once erected and maintained by scale, and to dramatically reduce the minimum efficient scale point in many manufacturing businesses. Market-back approaches to strategy are today insufficient for success in most established industries. This doesn’t mean that companies should disregard market signals; all strategy is set within that all-important context. But companies should consider both external market prospects and the internal capabilities system required to exploit these prospects successfully and sustainably. The focal point of your strategy should be where these two perspectives intersect.

As you take the journey to coherence, you and your company will move away from all of these incoherent habits and toward full commitment to success in the activities that matter. Since some people—inside and outside your company—won’t intuitively recognize the logic of your strategy, you will have to clarify it for them. They may include the board and executive team, along with your employees, investors, customers, and suppliers. Learn to communicate your way to play and its rationale clearly and consistently, time and again, in the same language. Bring others in your company to a point where they can do the same.

Make the most of the coherence you already have. Every company we’ve ever seen has had pockets of coherence that can be exploited from day one. Procter & Gamble and 3M invested heavily in corporate R&D during the 2000s, precisely for this reason: each company’s innovation capability was already highly valued, but not widely deployed enough. By publicizing it (for example, with P&G’s Connect and Deliver program), they encouraged people within the company to think about applying their innovation systems to a broader range of products and services.

Use every growth program, cost-reduction effort, or functional strategy as an opportunity to reinforce your way to play. Set a policy, for example, that your company will only benchmark distinctive capabilities, relevant to your way to play—regardless of which industry you find them in. Think in terms of coherence every time you outsource: is it a distinctive capability that you should keep in-house or a capability that you can buy? Judge shared services the same way. Which functions are linked to distinctive capabilities and thus deserve the most investment? When you promote or transfer people, among other factors, consider the impact this will have on critical capabilities.

Find ways to recognize and unravel the incentives and habitual operations that steer your company toward incoherence. For example, empower your functional leaders to give priority to requests that are tied to the chosen way to play and capabilities system. Guard against the natural human tendency to label everything as connected to your way to play and capabilities system, so that it gets support or avoids the cost-cutting ax.

In Chapter 12, we’ll look more closely at your role as the leader. For now, it’s enough to remind yourself of Mahatma Gandhi’s famous quote: “We need to be the change we wish to see in the world.”3 If you are leading this effort, people will look to you to be an example of coherence. That will be your responsibility—and, you may find, it will also be your pleasure.

Getting Started

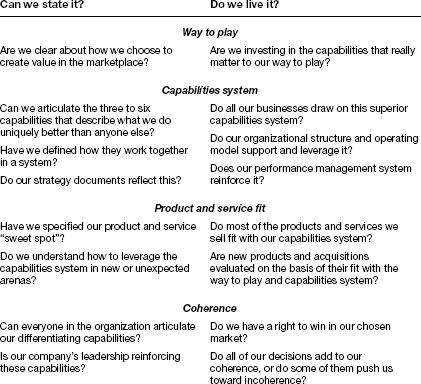

To begin with, complete a coherence test of your company (table 3-1) —a diagnostic assessment of the coherence that currently exists in the thinking and actions of your senior leadership. This diagnostic exercise will challenge your perceptions and those of your colleagues. You may be surprised by how your existing perceptions of your supposedly best products and services, your highest-growth markets, or your most significant competitors differ.

Table 3-1

The coherence test

In a small group, talk through the answers to these questions as candidly as possible. This exercise benefits from more than one person’s perspective. The two columns of questions reflect that incoherence has two sources—strategic and operational. The more questions to which you can truthfully answer “yes,” the more coherent your company.

Source: Adapted from Paul Leinwand and Cesare Mainardi, “The Coherence Premium,” Harvard Business Review, June 2010, 86–92.

This exercise will give you a more complete understanding of where you stand; keep it at the back of your mind as you read through the next six chapters, as we’ll revisit it in chapter 10. Use this diagnostic more than once—it’s a valuable tool to measure and track your company’s progress on your journey to coherence.

It’s difficult for individuals to objectively take stock of their capabilities—to assess what they’re good at and what they’re not—and it’s even more difficult for companies. Try to look as dispassionately at your company as a knowledgeable investor would. Be prepared for the coherence test to show that your senior team is not as aligned as you expected. We sometimes ask corporate leaders, “If we were to interview everybody in your management team and ask them to identify the capabilities that are most critical to the advantage in your business, would they describe the same three to six things?” There is always a moment’s pause—and then a recognition that the leaders are not as aligned as they would like to be. But there is also generally a recognition of the chance to focus, to eliminate distraction, and to move past consensus to a new type of choice.

Discovering the Elements

In the rest of this book, you will read about the choices needed to develop your own strategic elements: how your way to play, your capabilities system, and your lineup of products and services can all fit together. It is tempting to think of these as three separate elements, conceived individually. One could imagine selecting a way to play in light of your perception of your market, figuring out a capabilities system close to the one you already have, and then deciding which products and services to keep or sell.

But, as we’ve seen in this chapter, a capabilities-driven strategy doesn’t work that way. So as you read the next three chapters, imagine yourself entering your own discovery phase for each of these elements: chapter 4 on the way to play, chapter 5 on the capabilities system, and chapter 6 on the fit of products and services. Then in chapters 7 through 9, you’ll learn how a capabilities-driven strategy can drive value in your company. In chapters 10 through 12, you will learn how to lay the groundwork for the rest of your journey and how to live coherence in your company every day.