CHAPTER SIX

Company Governance

Fulfilling Broad Mission and Purpose

THE GOVERNING BOARD of Western companies has traditionally been viewed as the owners’ eyes and ears, ensuring that company executives take prudent risks to optimize investor value and engage in no self-serving behavior or malfeasance while doing so. But drawing on the broad sense of mission and purpose that defines the India Way, Indian directors have become more deeply engaged in guiding company directions with less of an eye or an ear on the shareholders and more of a concern for the community and the country.

The conventional American model of corporate governance is notable for its formal clarity and conceptual simplicity. Company directors are elected by the firm’s stockholders—one share, one vote—to pursue and protect investor interests. Drawing on the principal-agent academic theory, directors are required to monitor the managers on behalf of the owners, but they are proscribed from managing the managers. The Business Roundtable, an association of the chief executives of America’s largest firms, stipulated the behavioral path as clear as any. “The board of directors has the important role of overseeing management performance on behalf of shareholders,” it declared; “directors are diligent monitors, but not managers, of business operations.”1 Directors are in the boardroom to keep executives’ feet to the owners’ fire, the American model asserts, and they must not become directly engaged in the company’s business practices.2

The failures of Enron, WorldCom, Tyco, and other firms in 2001–2002 were partly attributed to the failure of their directors to even monitor their managers, let alone manage them.3 In the wake of that evident malfunction, the U.S. government and the New York Stock Exchange sought to strengthen the monitoring function through the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 and new listing requirements in 2003. The first required that directors create an audit committee comprising independent nonexecutive directors; the second, that directors establish a compensation committee and a governance committee also composed of independent nonexecutive directors. Both initiatives tightened the definition of independence. The New York Stock Exchange further pushed for the creation of a “lead” independent nonexecutive director who would serve as a monitoring counterweight to the common American practices of fusing the roles of chief executive and board chair. The boards of virtually all major publicly traded American companies had by 2008, according to one annual survey, created the three stipulated committees of independent nonexecutive directors and appointed either a nonexecutive chair or an independent nonexecutive lead director.4

In theory, at least, these measures strengthened the monitoring hand of the board. Still, in 2009, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) announced that it would investigate the governance failures at a host of financial institutions. Regardless of that outcome, the American model of independent, nonexecutive boards vigorously overseeing managers on behalf of shareholders has become not only a Wall Street convention but a global model, promoted heavily by international investors and multilateral institutions such as the World Bank and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development.5

Many countries, including India, have been swayed by that influence. The Indian counterpart to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, the Securities and Exchange Board of India, commonly known as SEBI, promulgated a new set of rules in 2004 under the rubric of “Clause 49.” Among the most important features was a requirement that closely reflected U.S. thinking: the number of independent nonexecutive directors should constitute at least half of the board. The implication for the oversight function was obvious: more independent nonexecutive directors would strengthen the monitoring of managers.

Riding the Tiger

As in the United States, India has had its share of monitoring failures in the wake of Clause 49, most notably in the case of Satyam Computer Services, the country’s fourth-largest information technology outsourcing firm. Satyam’s founder and chief executive, Ramalinga Raju, asked his board in December 2008 to approve a $1.6 billion acquisition of two other companies, and after some debate, the board unanimously supported the proposal. Institutional holders, however, revolted against the plan, dumping Satyam’s stock in such a frenzy that the company lost half its market value in a single day’s trading. Their complaint: the targeted companies were founded by the CEO’s sons. Both firms carried the name Maytas—Satyam spelled backward—and both operated in the unrelated industries of infrastructure and real estate, building shipping ports and auto roads, not information highways. Chief executive Ramalinga Raju backed off from the acquisitions, but his reputation was fatally compromised, and several prominent nonexecutive directors resigned, their reputation for vigilance severely damaged.6

The story did not end there, though. Just three weeks later, Satyam’s chief executive unloaded a far larger bombshell. In a January 7, 2009, letter to the Bombay Stock Exchange, Raju candidly admitted to phony accounting, inflated earnings, and a claim of more than $1.1 billion in cash, when in fact the company held just $66 million. “What started as a marginal gap between actual operating profit and the one reflected in the books of accounts continued to grow over the years,” he explained, and then it “attained unmanageable proportions as the size of company operations grew.” The gap between the real and the reported extended even to employment numbers: the company had publicly claimed that it employed 53,000, but the actual number evidently was some 10,000 less. In the end, said Raju, it was “like riding a tiger, not knowing how to get off without being eaten.”7

Raju’s disgrace and Satyam’s fall were fittingly termed “India’s Enron” by many observers. But as spectacular as the collapse was—on both the personal and the corporate fronts—it is more the exception than the rule. Malfeasance charges did not sweep across the Indian business landscape, and the obvious failure of the Satyam board to do even minimal monitoring did not emerge as the Indian norm. Moreover, as much of the developed world plunged into recession, Indian business remained relatively resilient. What some had deemed a liability—India’s distinctive approach to governance—might have even proved an asset.

Ownership and Governance

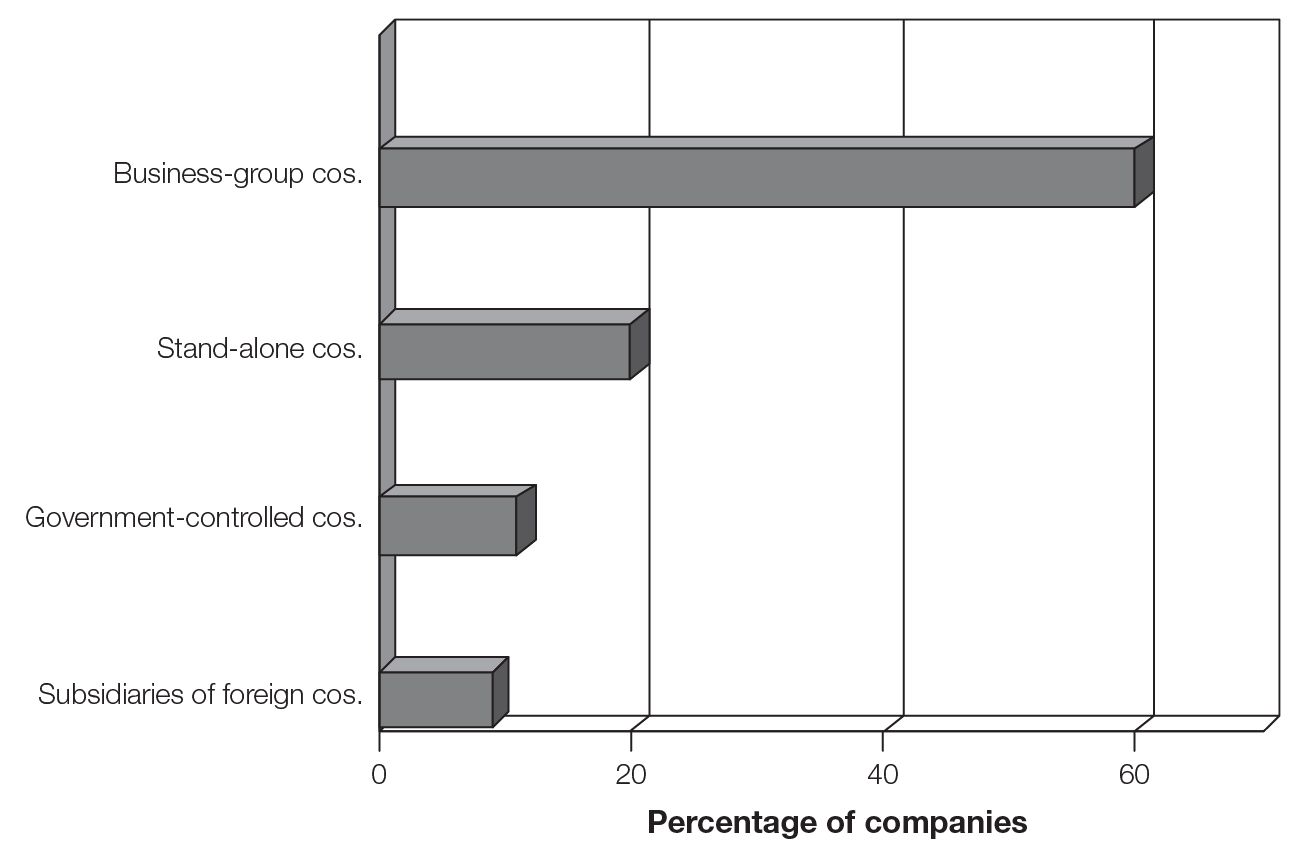

Corporate governance in India differs substantially from that of the United States in the ownership structure of its firms, with many firms operating under the umbrella of business groups, and a significant number of infrastructure firms owned by the government. The roots of the distinctive way of Indian corporate governance can be traced in part to the very different ownership structures of its largest companies. Most were publicly traded, but the ownership of many remained concentrated in the promoter family’s holdings.8 While most large American firms had ownership profiles with a large number of institutional investors each holding a sliver of the firm’s stock—which, taken together, constituted a substantial majority of shares—the ownership of large Indian companies generally fell into four distinct patterns.

A first group included publicly traded companies that had a majority share of their ownership in the hands of a business group, which was in turn controlled by a founding family. Among the most prominent of the business groups were those of Aditya Birla, Godrej, Anil Dhirubhai Ambani, Reliance Industries, and Tata. Most of these groups had established operating companies in disparate industries ranging from software and steel to retail and telecommunications. 9 A very few of America’s more notable corporations fell in the general category of family control, often exercising authority through a separate class of stock, as at Ford Motor Company, The New York Times Company, and The Washington Post Company, but none of the American companies operated as a business group in the full Indian sense.

A second group of Indian companies consisted of stand-alone, publicly traded companies such as ICICI Bank—a model far more familiar to American investors. A third group was made up of what might become an increasingly familiar American type as global ownership spreads: publicly traded subsidiaries of multinational corporations, such as Hindustan Unilever. The fourth group, largely unfamiliar to those in Western settings until the financial crisis of 2008–2009, encompassed publicly traded but still largely government-owned companies, such as the State Bank of India, a legacy of the pre-1991 centrally planned economy.

Just as Indian companies differed in ownership structure from many American firms, so did they differ in how owners sought to exercise their rights. For the most part, the largest owners of America’s premier corporations were institutional investors, whose holdings rarely exceeded 2 or 3 percent of total outstanding shares and who, in any event, had proved generally reluctant or unable to exercise their ownership rights.10 Instead, the U.S. model was premised on an active market for corporate control that imposed an external discipline on the directors’ monitoring of managers. Companies whose boards failed to fulfill their fiduciary duties found themselves subjected to unwanted takeovers in an active and independent equity market, and poor company governance was often punished by hostile acquisition or proxy battles to replace underperforming directors.11

Business-group companies constitute the dominant Indian form, as seen in figure 6-1, and they have often set up long-standing “shadow” boards comprising family-dominated operating committees. As one might expect, the role of the formally appointed boards of such companies was largely diminished in comparison to U.S. boards. Yet we found that whatever the ownership structure, Indian executives generally placed less weight on the board’s monitoring function than was common in the West—at least in part because Indian firms and their directors faced a less active market for corporate control than did their U.S. counterparts. 12 But to note that Indian boards as a rule monitor less than American ones is not to say that they have a less significant influence on the companies they serve. In this as in so many other aspects of corporate life, the India Way simply conceives of a director’s role in more holistic terms.

Ownership and control of 500 large Indian companies, 2006

Source: Rajesh Chakrabarti, William Megginson, and Pradeep K. Yadav, “Corporate Governance in India,” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 20, no.1 (2008): 59–72.

Values-Based Governance

A first indicator of the distinct Indian governance path came when we asked business leaders, “What are the two most distinctive aspects of corporate governance practices in India compared to the U.S.?” As seen in table 6-1, only a handful of the executives—just six of the more than one hundred we interviewed—saw little or no difference in the governance practices of the two countries. Substantial numbers, by contrast, viewed Indian governance in a state of transition or as a distinctive product of the country’s regulatory regime or ownership structure.

Executives’ perceptions of distinctive Indian corporate governance practices compared with those prevalent in the United States

| Question: “What are the two most distinctive aspects of corporate governance practices in India compared to the United States?” | |

|---|---|

| Distinctive characteristics of Indian corporate governance practices | Percentage |

| In a state of transition | 24 |

| Product of India’s regulatory regime | 23 |

| Related to family or promoter ownership | 11 |

| Lack of director independence | 11 |

| Lack of regulatory enforcement | 8 |

| Inconsistency across companies | 6 |

| Long-term focus (compared with short-term focus in the United States) | 6 |

| Importance of other stakeholders, such as employees and communities | 6 |

| Not much difference between India and the United States | 6 |

The transitional state of Indian governance was well captured by Rahul Bajaj, the chief executive of the Bajaj Group and chair of a committee established by the Confederation of Indian Industry in 1996 to propose governance guidelines. 13 “We are behind the U.S.,” he observed, adding that Indian companies were still in the process of borrowing from abroad. At the same time, many of the companies were developing indigenous solutions to the challenges of effective governance in India, and a common theme in their solutions was an emphasis on what some have termed a values-based governance system in contrast to a rules-based approach. 14 The first is premised on a set of shared values and norms among directors, executives, and regulators on what constitutes good governance. The second is predicated on the assumption that common values and norms are not sufficient and specific rules are therefore required. American governance increasingly became more rules based in recent years, while India followed the values trail.

Compliance Versus Entrepreneurial Boards

The two approaches to governance were nicely delineated by Thomas Perkins, founder of the Silicon Valley venture capital firm Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers. A nonexecutive director of Hewlett-Packard from 2002 to 2006, Perkins resigned in protest over the board chair’s handling of an investigation of unauthorized disclosures by board members. From that unhappy experience, Perkins drew a distinction between what he termed a compliance board and an entrepreneurial board. The former described the Hewlett-Packard board he had served on, while the latter should, in his view, characterize how boards actually operated. Directors serving on the first primarily saw their role as enforcing regulatory rules and strictly monitoring management. Directors serving on the second primarily viewed their role as a partnership with management to create new products and services. 15

B. Muthuraman, the managing director of Tata Steel, drew a similar, sharp distinction between boards that focus on rules and those that focus on values. “The Tata Group is less rules based and more values based,” he observed. “We have always believed you really cannot frame rules for corporate governance.” Recognizing the inherent limitation of relying upon formal rules, he and other Tata executives and directors had thus opted for building the values-based model: “The spirit of corporate governance and the value systems” that they brought to the boardroom were far more critical for governance in the Tata Group, he said, than what he saw among American firms, where boards, in his own experience, were “less spirit based and far more procedural.”

Nonexecutive directors in Indian boardrooms take up more of a strategic partnership role with company executives, akin to Perkins’s role of working with management to create and market new products and services, and comparatively less of a shareholder-monitoring or rules-based role, in keeping with the American approach. Instead of functioning solely as the eyes, ears, and enforcers for absent owners, many directors had taken on the additional role of working with company executives to set the right direction for the company. Protecting shareholder value was not ignored, but Indian directors incorporated the concerns of a range of constituencies—just as Indian executives do—in reaching board decisions in partnership with management.

Socially Responsible Governance

The single most distinctive feature of corporate governance across the Indian companies we studied was this determination to balance the interests of the firm’s diverse stakeholders, all the groups that have a claim on what the company does, including employees, customers, and community. What was especially striking was the emphasis on the broader community, which extended from the immediate vicinity of the business out to encompass the entire nation.

At an international forum in 2006, the chief executive of a well-known American corporation declared proudly that its headquarters happened to be in the United States, but since its manufacturing and sales were worldwide, he did not consider either his company or his leadership role as distinctly American. Few, if any, Indian executives and directors would wrap themselves in such a countryless banner. Though publicly traded and often global in operations, Indian companies were governed in ways that also pointed their decisions toward national purpose rather than eschewing it.

Consider the chairman of the Godrej Group, Adi Godrej. His group’s governance, he baldly stated, was “directed towards the good of the company and not necessarily the good of one or the other of the shareholders.” He added that the Securities and Exchange Board of India, the Indian equivalent of America’s SEC, was properly concerned with protecting minority shareholders—those who were not part of the founding family or the primary owner—from exploitation by the dominant owners. But aside from meeting that obligation, the governing board’s role was to optimize the company’s success, broadly defined. “I think the most important thing in the Indian situation,” he concluded, “is to ensure the corporate governance practices are directed towards the good of the company. If the corporate governance practices promote the good of the company, then all stakeholders benefit.” In keeping with that sentiment, the Godrej Group had constructed schools, medical clinics, and living facilities for employees on a massive scale unknown among American companies, where directors and executives were far more likely to see employee welfare as a drag on shareholder value rather than an asset for company growth.

A Long Tradition of Social Engagement

The focus on social responsibility was particularly evident among promoter-led or family-owned businesses, some with social engagements dating back decades. Jamnalal Bajaj, the grandfather of Rahul Bajaj, chairman of the Bajaj Group, had served as a vigorous supporter of Mahatma Gandhi’s movement for independence and an unswerving proponent of viewing business as devoted to a cause, not just the owner’s enrichment. In the family memory of grandson Rahul Bajaj, Jamnalal Bajaj was known by Gandhi as the “merchant prince” for insisting that companies place honesty over profits and that they serve all parties to the enterprise, not just the owners. 16

The predecessor of Tata Steel, the Tata Iron and Steel Company, had constructed an entire town in the state of Bihar, with schools, hospitals, roads, and other infrastructure around its steel-making facilities to create a fully supported living environment for its employees. As independent nonexecutive director of the Tata Group J. J. Irani put it, the firm has a responsibility to a triple bottom line that “constitutes its environmental obligation, its social responsibilities, and its financial bottom line.”17

Even among Indian companies with little history, executives and directors pointed to the importance of serving the nation, not just the stockholders. Mallika Srinivasan, a director of Tractors and Farm Equipment Ltd., a Chennai-based manufacturer established in 1961 with annual revenue in 2008 of more than $750 million, spoke compellingly of the obligation of executives and directors to look well beyond shareholder value. Almost anywhere companies operated in India, she said, they were encircled by throngs of destitute people. Infosys, for example, maintained a first-world campuslike facility just feet from the impoverished masses of Bangalore, and the same for the surrounds of Tractors and Farm Equipment locations. Concerns about “corporate social responsibility and good governance are related to the state of development of the country,” Srinivasan said. “We are seeing all these islands of prosperity surrounded by so much poverty.” Social needs were stark, governmental interventions were inadequate for meeting them, and firms and their directors were thus duty-bound to step forward.

Doing Well by Doing Good

The focus on social responsibility transcended company self-interest, but executives and directors found material value in it nonetheless. The immediate costs were balanced by the promise of long-term financial advantage, a luxury that many American executives and directors had been unable to embrace, given the pressure from Wall Street for quarterly results.

Managing director B. Muthuraman of Tata Steel, for instance, saw his company’s costly engagement in the community as a motivational benefit for the firm’s eighty thousand employees. The Tata name, he said, had become a “very powerful brand,” and it, along with the respect that the Tata Group had built in the broader community, had proved invaluable for recruiting and retaining employees at Tata Steel. Short-term a loss, but a long-term gain.

The Ambivalence of Governance

One of the prices of India’s booming economy and increasing worldwide presence has been pressure to conform to global norms on multiple fronts, including corporate governance. Accordingly, SEBI moved in the direction of stronger rules for protecting shareholder rights. But the changes have not been entirely welcome. While Indian executives generally want to be viewed as world-class players, they are often reluctant to see their boards—and their businesses—become more rules oriented.

At the time of India’s independence, four stock markets were already in operation, though their turnover was tiny by today’s standards. Still, they had established listing and trading requirements, and subsequent legislation further strengthened shareholder protection and financial disclosure. The Companies Act of 1956, for example, held that a company’s financial statements were the responsibility of the governing board, and it made directors accountable for ensuring that the company complied with contemporary accounting standards. But it was not until the reforms of 1991 that India moved toward formalization of its governance system. Driving the effort were both the need to attract foreign investment, which required even greater transparency in financial reporting, and the partial privatization of banking, which also placed a premium on reliable disclosure by borrowing firms. The rapid growth of companies in the wake of the reforms and their own burgeoning need for equity and debt added still another force for formalization.

Securities and Exchange Board of India

In 1992, at the outset of the reform movement, the government created the Securities and Exchange Board of India to oversee corporate governance and capital markets. Eight years later, in 2000, SEBI put forward a set of corporate governance guidelines that included specific requirements for board composition and the roles of the chief executive, board chair, and key committees. If the positions of the chief executive and board chair, for instance, were held by different individuals, at least 33 percent of the board must be independent nonexecutive directors; if the two roles were instead combined, at least half the board should consist of independent nonexecutive directors. The board’s audit committee was to have at least three outside board members, all with financial experience and expertise. The rationale behind the reforms was straight from the rules-based view of governance. Strengthening the role of the nonexecutive independent directors would make for stronger monitoring of managers and better protection of shareholder rights. 18

Since the strengthened governance provisions were added to the forty-ninth section of the Listing Agreement, it came to be known as Clause 49, and it specified a host of governance requirements, including disclosure of directors’ fees and addition of a section on governance in the annual report. In 2002, SEBI constituted a committee chaired by Infosys’s Narayana Murthy to improve Clause 49’s requirements, and the revision, issued in late 2004 and implemented at the start of 2006, further tightened the definition of independent directors, strengthened the role of the audit committee, and enhanced the accountability of the chief executive and chief financial officer. Companies were required to establish risk management controls and issue a governance code of conduct, and officers were henceforward required to certify the efficacy of all internal controls, ranging from manufacturing to sales, legal, and even human resources. The parallels with the thrust of the U.S. Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 were evident, including training for company directors, more specific guidelines for the financial literacy of audit committee members, and annual performance evaluations for nonexecutive directors by their peers.19

Sarbanes-Oxley, Like It or Not

As stringent as they were, the Clause 49 guidelines remained more lax than those found in the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, especially regarding financial disclosure and transparency. But many Indian corporations anxious to list internationally made up for the difference by adopting Sarbanes-Oxley rules despite their lengthy and expensive requirements. Some companies went all the way and listed directly on the New York Stock Exchange. Among the eleven that had done so by 2009 were several prominently mentioned in these pages: Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, HDFC Bank, ICICI Bank, Tata Motors, and Wipro. The rush to adoption, though, was not always done with a smile.

HDFC’s Deepak Parekh, for one, described as a mixed blessing the heightened governance vigilance that came with full Sarbanes-Oxley compliance. “We have to follow Sarbanes-Oxley, whether we like it or not,” he said. “We know it is very onerous, we know the reporting requirements are strenuous, and we have an army of people involved in that, but the worry we have is that we don’t know, when we make a mistake under Sarbanes-Oxley, where we will be hauled up.” HDFC did not draw more than 10 to 15 percent of its capital from the U.S. equity market, but even for that, Parekh had concluded that the burdensome listing in New York was worth the price. Others have been migrating in the same direction. “I think we are slowly moving towards the rest of the world,” said Sarthak Behuria, chairman of Indian Oil Corporation. He and many other Indian companies, he said, were looking to list their companies in the U.S. as American Depository Receipts—a device that allows investors in the United States to trade in non-U.S. securities without engaging in cross-border transactions—to access the large capital markets that were simply unavailable at home.

While the Indian leaders we interviewed almost to a person described the SEBI requirements for listing companies in India as onerous, and the same for SEC requirements for listing firms in the U.S., many also conceded that the new rules might actually have facilitated the nation’s economic expansion, as suggested by a research finding that good corporate governance has generally led to stronger economic growth and better performance of companies during a financial crisis.20

“By and large, I think the shift in the last ten years in governance has been dramatic,” said ICICI’s K. V. Kamath. “In a developing country context, it was thought to be impossible.” But the “entire process of the way the SEBI has structured governance, the way they have heightened reporting and heightened best practices, and the way industry went ahead embracing this and how it has been popularized will all become good case studies for other countries.”

Still, the diffusion of rules-based governance is far from complete. One survey of Indian companies in early 2007, for instance, reported that 57 percent had still not brought their boards into compliance with some of Clause 49’s stipulations. Another study, this one in 2004–2005, found that 70 percent of a sample of 1,255 companies had complied with 80 percent or more of Clause 49’s seventeen major codes.21 As Jagdish Khattar, managing director of Maruti Suzuki, India’s leading car maker, told us, “There is a lot of talk about it, but I think that we have a long way to go” to achieve full compliance.

Recruiting Independent Nonexecutive Directors

The thrust of Clause 49 has been to strengthen the oversight role of independent nonexecutive directors by increasing their numbers on the board, expanding their influence over audit and compensation, and making their role more transparent. Ideally, this should spawn boards devoted to monitoring company managers and protecting shareholder rights. The reality, though, is that Indian board members, more so than their American equivalents, tend to be recruited for almost anything other than their monitoring potential.

When it comes to monitoring management, the thrust of a rules-based approach, independence of thought, should be among the leading criteria, but as displayed in table 6-2, it ranked far down the list in our surveying, with business experience, personal reputation, and professional expertise far ahead of it. Conversely, for values-based governance, with its emphasis on entrepreneurship and collaborating with management, experience and expertise should rank high up on the list, just as they do. While the SEBI regulations pressed for strengthening the nonexecutive directors’ oversight function, the Indian executives reported that when they recruited nonexecutives to their board, they used the opportunity to strengthen the directors’ capacity to work in partnership with them. These attributes of directors were also closer to the entrepreneurial model referred to by Hewlett-Packard director Thomas Perkins rather than the compliance model that Perkins feared had come to pervade the American landscape.

Executives’ criteria for selecting nonexecutive directors for the governing board

| Question: “What are the two most important criteria you have used in selecting nonexecutive directors?” | |

| Criteria for selecting nonexecutive director | Percentage |

| Professional experience, diversity of experience | 38 |

| Reputation, credibility, track record, stature | 26 |

| Domain or functional expertise | 15 |

| Independence of thought | 10 |

| Integrity and character | 5 |

| Commitment to serving on the board | 6 |

When asked to describe the role that nonexecutive directors play in the boardroom, the Indian executives—many of whom also served as nonexecutive directors of other firms—consistently stressed their value in providing substantive guidance on business issues and virtually never referenced their monitoring function.

“We’d Be Stupid Not to Use His Skills”

The nonexecutive component of Mahindra & Mahindra’s board provides an example of how these survey results play themselves out in practice. Of the twelve directors, eight are independent, and they bring extensive background in banking and finance (Deepak Parekh, chairman of HDFC Ltd., and Narayanan Vaghul, chairman of the board of ICICI Bank Ltd.); manufacturing (Nadir Godrej, developer of the animal feed, agricultural inputs, and chemicals business of Godrej Soaps and other associated companies); technology and research (M. M. Murugappan, a member of the supervisory board of the Murugappa Group of companies, responsible for technology and research); consumer products (A. S. Ganguly, chairman of Hindustan Unilever Ltd. from 1980 to 1990 and a member of Unilever’s main board from 1990 to 1997); law (R. K. Kulkarni, senior partner of Khaitan & Company, one of India’s leading law firms); strategy consulting (Anupam Puri, thirty years with McKinsey & Company); and insurance (Thomas Mathew, managing director of Life Insurance Corporation of India).

None of these nonexecutive board members brought to the post special experience or expertise in monitoring management for shareholder value. What they added, instead, was broad and substantive knowledge of the business world generally and of special niches in particular. “It’s not because we structured it that way,” said Anand Mahindra. “It just happens to be the particular skill sets of the people we have on the board.” He singled out two directors to substantiate his point: one, Anupam Puri, was an ex-director and senior partner of McKinsey who had started up McKinsey in India. “We’d be stupid if we didn’t use his skills,” explained Mahindra, “particularly since it cost a lot less than actually hiring him. He heads up an investment committee that we have, and that includes a fairly aggressive process that looks through a lot of the major investments or new ventures or acquisitions that we are considering in the parent company.” A second director, A. Ganguly, was not only exchairman of Hindustan Unilever; he also had headed Unilever’s worldwide R&D and still served on the board of British Airways. “A person like that brings a huge maturity and perspective,” offered Mahindra, “so we’ve actually used him a lot, too.”

Key Decisions

In our interviews, we also asked the Indian business leaders about the value that their nonexecutive directors had brought to key company decisions in the areas of acquisitions, divestitures, and strategic alliances, arguably among the most important issues that come before a board.22 The responses, shown in table 6-3, point to the value of such directors as partners with company executives in reaching strategic decisions. The nonexecutive directors provided diverse inputs and insights, offered independent assessment of proposed actions, posed challenging questions, and contributed special expertise to strategic decisions. No one we interviewed said that their nonexecutive directors contributed much in the way of a monitor’s vigilance to the company’s decisions on acquisitions, divestitures, or alliances.

Value of nonexecutive directors for company decisions on acquisitions, divestitures, and strategic alliance

| Question: “When it comes to acquisitions, divestitures, and strategic alliances, what value have nonexecutive directors brought to the decisions?” | |

| Value of nonexecutive directors | Percentage |

| Diverse inputs and insights into strategic planning and decision making | 40 |

| Independent views providing checks, balances, and restraints | 21 |

| Challenging questions and playing devil’s advocate | 15 |

| Functional expertise in areas of finance, legal, tax, regulations, and mergers and acquisitions | 19 |

| Limited value | 5 |

| Monitoring shareholder value in acquisitions, divestitures, or alliances | 0 |

The Indian executives repeatedly stressed the importance of their nonexecutive directors for reaching key decisions, seeing them more as discussion partners than adjudicating monitors. Adi Godrej of the Godrej Group said that his nonexecutive board members “brought tremendous value” to his management team’s decisions on transactions. Pantaloon Retail’s Kishore Biyani offered much the same assessment. He had brought a number of acquisition and alliance proposals to his board, and the directors had pushed back against a substantial fraction. “The key role our board members have played in terms of decision making on these issues has been very, very major,” he said. Out of ten proposals over a given period, they had on average rejected three. “Whenever there has been a discussion on a particular alliance or an acquisition, I think the outside board members have been well positioned and aware of the facts about what we are getting into. Everybody has a point of view in terms of the company’s evolution—what one should and should not do—and I think they have played a key role in forcing us to think through what we are doing.”

In one instance, Biyani recalled, his outside directors had rejected a proposal after they concluded that the acquisition would require too much of Pantaloon’s capital. In another, the directors rejected a proposed acquisition because of the quality of the company at the top, finding that the target’s governance did not meet Pantaloon’s standards. The content of his board’s dialogue and its decision-making criteria were focused on the business issues in the proposed acquisitions and alliances, not their potential for creating or damaging shareholder value, though the former always has implications for the latter. In the American boardroom, by contrast, immediate impact on shareholder value is typically a far more dominating concern.

Part-Time Service

Indian business leaders warned against overinterpreting the worth of the values-based decision-making partnership with the nonexecutive directors. Nonexecutive directors by definition can devote only a small fraction of their work year to the company and are thus inherently limited in the depth of what they know or the time they can take to render informed guidance. Rahul Bajaj said that for some companies, governance meant little more than “filling up the boxes, ticking them off to show that they have met all the requirements. In most Indian companies, that is the spirit of the thing, so these independent directors don’t get much time to provide value even though they have the capacity to do so.” After directors meet their board committee requirements, “very little time is left for strategic input” into “strategic discussions.”

Still, the picture that emerged from our interviews was one of values-based governance, with a focus on guiding good strategic decisions more than appraising management performance. Nonexecutive directors were largely chosen for the professional knowledge and business experience that they would bring to the firm’s strategy development and key actions. Their place in the informal networks of Indian business and society did not appear to be a primary consideration in selecting them, though the preference expressed by some of the business executives for nonexecutive directors of reputation and stature no doubt partly reflected that consideration. Nor was there evidence that the business leaders sought prominent figures primarily for their symbolic value rather than their strategic contributions to the key decisions—a practice common with outside directors in the U.S. To guide the right strategic decisions, then, the nonexecutive directors played a check-andbalance role, raising questions and providing guidance before important decisions were finalized, focusing more on the long-term development of the company than on short-term growth in shareholder value.

Convergence of East and West?

One side of a long-standing academic debate contends that governance practices of large companies worldwide are likely to converge on a set of shared practices. As large companies in major economies search for capital, goes the rationale, they will increasingly enter a worldwide equity market, where they will encounter equity investors increasingly global in scope. Regardless of their originating nation, the major players will acquire a set of shared principles and norms for good corporate governance. The other side of the debate expects only modest convergence at most. Distinct country traditions and national regulations are likely to thwart the global equity-market pressures for convergence, the argument contends, preserving much that is unique and effective in the respective national governance systems. In the end, major players such as China, India, and the United States will each sustain their own ways of governing.23

As seen in table 6-4, the Indian business leaders were in substantial agreement with the first side of that debate. Asked “Will your governance practices eventually converge with those of the U.S., or will they remain distinct?” slightly more than half concurred with the convergence forecast. Smaller fractions anticipated convergence with the governance models of the United Kingdom or other countries, and just one in ten forecast no convergence at all.

Convergence of Indian governance practices with those of the United States

| Question: “Will your governance practices eventually converge with those of the United States, or will they remain distinct?” | |

| Convergence with U.S. governance? | Percentage |

| Yes | 51 |

| Convergence more expected with U.K. or other national models | 19 |

| Yes, but with some modest differences | 13 |

| No | 10 |

| Movement toward a middle ground or hybrid | 7 |

Though a majority of the business leaders anticipated convergence with the U.S. model, some forecast that the U.S. model would at the same time move toward the Indian model as well. One in five of the executives foresaw convergence around a different end point, a global best-practices model, which would include practices from the United States, India, and elsewhere. Not surprisingly, the companies that most anticipated convergence of Indian governance with U.S., U.K, or other non-Indian models were those whose revenues came heavily from international clients. Overall, however, nearly half of the executives believed that Indian corporate governance would retain some of its most compelling features, including its relative emphasis on a values-based approach, and its stress on the worth of human capital as much as stockholder capital.

B. Muthuraman of Tata Steel spoke for many: “I’m not a great admirer of the U.S. corporate governance practices at all. By framing rules, you cannot improve corporate governance. You lay down more rules, and they get broken more.” By contrast, in India, in “improving your value system, you can improve the corporate governance practice.” Many concurred with the call for a continued strengthening of values-based governance norms rather than an imposition of more rules.

No Guarantees

On the surface, the spectacular executive fraud at Satyam Computer Services would suggest that India’s preference for a value-based board approach imperils shareholder interests. Surely, a board more attentive to rules and monitoring compliance would have heard warning bells going off. Yet a close inspection of the Satyam board reveals—as with the Enron board—a relatively strong set of independent nonexecutive directors whose composition and outward appearance would appear to meet SEBI standards for rules-based governance compliance. The board included a majority of independent, nonexecutive directors who brought strong and diverse experience to the boardroom, including expertise in venture capital, corporate governance, and public affairs. So evident was the rules-based compliance with the principles of good governance that just months before its chief executive confessed to massive fraud, the World Council for Corporate Governance presented Satyam with its Golden Peacock Award for Excellence in Corporate Governance. Similarly, the Enron board had been dominated by highly experienced and independent nonexecutive directors just before the fall, and the board had even separated its chair and chief executive roles.24

The moral, then, is an old one: in business as in life, there are no guarantees. If the rules-based approach helps focus attention on protecting and growing shareholder values, as ample research has demonstrated, it is no assurance against improper executive behavior if the boss’s values are flawed.25 Moreover, a laserlike focus on rules and compliance inevitably must direct attention and energy away from the other stakeholders that Indian executives and directors have generally avowed to benefit along with shareholders. Throughout Indian society and the business community in particular, corporate social responsibility is a compelling goal, and balancing diverse interests is a prescribed responsibility of company leadership.

Delivering Value

The stakeholder-informed model of governance that the Indian business leaders have embraced stands in stark contrast to the principal-agent model that has dominated so much of the American approach to governance in recent years. The latter focused executive attention exclusively on the singular objective of delivering value to shareholders. Governing boards accordingly designed compensation packages for their executives that were intended to align decisions almost entirely around the delivery of shareholder value.

The prevalence of promoter- and family-controlled companies in India and their leadership in the community is particularly important in this context. Because some of the executives at these companies are also large owners or members of owning families, they need little special incentive to look after ownership interests and are more able than their counterparts in the United States to take a long view about what is good for their company. With that longer view, it becomes possible to see more opportunities for the interests of the company and the interests of the broader society to coincide.

Short-term, mutually exclusive trade-offs between acting to advance the company and spending to benefit the community are less pronounced in the longer run, where it becomes more evident that charitable giving and community outreach can build brand value and reputational capital, both of ultimate but little immediate benefit to companies and their owners.

Governance at Infosys Technologies

To illustrate many of these themes and to see how they interplay with one another, we briefly consider the governance of Infosys Technologies. While the company clearly met international standards for rules-based governance—it listed itself in both India and the United States—it managed at the same time to build a values-based governance model, and it has worked to draw the best from both models. The Infosys board, for instance, placed a premium on both the independence and the competence of its directors. Independence provided for director monitoring of management; competence provided for director dialogue with management. Directors could thus both hold executives’ feet to the fire and serve as advisers and sounding boards for executive decisions. By virtue of Infosys’s American listing, the board of directors also served to bolster company credibility with investors and customers outside of India.

Infosys Technologies early adopted a rules-based approach to governance. After the Confederation of Indian Industry put forward a set of good governance rules in 1999, Infosys was one of the first companies to embrace them. As a part of a commitment to global best formal practices, Infosys decided also to comply with the Euroshareholders Corporate Governance Guidelines of 2000 and those of the U.S. Conference Board Commission on Public Trust and Private Enterprise. Infosys embraced the UN Global Compact and the governance guidelines of six countries—Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, and the United Kingdom.26 In the same spirit, it adopted the U.S. generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) well before most other Indian companies, and in listing itself on NASDAQ, it embraced Sarbanes-Oxley as well.27

Infosys’s governance as a result became exemplary by any set of international rules-focused standards. For instance, Crédit Lyonnais, the French financial services company, ranked Infosys as having the best corporate governance of 475 companies that resided outside North America, Western Europe, and Japan. On a 100-point overall scale gauging such issues as reporting transparency and board independence, Infosys scored 91, while the average company scored only 58.28

In keeping with the rules-based model, Infosys also acted to increase its own operational transparency by reporting revenues separately for its major segments, and it brought its board into compliance with SEBI’s Clause 49 requirements. Eight of Infosys’s fifteen directors were independent nonexecutives. The audit, compensation, investor grievance, nominations, and risk management committees were all composed of independent directors.

But Infosys has also been a practitioner of the values-based approach to governance. The directors, for instance, reflect a wide range of expertise from academe, consulting, and industry, with both domestic and international experience.29 “The major value” of the nonexecutive directors, said chairman Narayana Murthy, has been in “asking questions that make us rethink our assumptions. That makes us look at issues we may have missed and think about alternatives.” At a recent board meeting, for instance, the executives and directors debated the synergistic merits of several acquisitions and alliances for the better part of three hours. The board went back and forth on the strategic issues—what were the downsides to combining different company cultures? Would management have the “bandwidth” to manage a proposed acquisition? If it were completed, would the two firms be able to cross-sell their services to each other’s customers?

Infosys Technologies

Board of Directors, 2009

EXECUTIVE DIRECTORS

N. R. Narayana Murthy, founder, chairman, and chief mentor. N. R. Narayana Murthy founded Infosys in 1981 along with six other software professionals and served as the CEO of Infosys for twenty-one years. He obtained his BE (electrical) from the University of Mysore in 1967 and MTech (electrical) from the Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur, in 1969. Several universities in India and abroad have conferred honorary doctorate degrees on him.

Nandan M. Nilekani, founder and cochairman. Nandan Nilekani has been cochairman since 2007, and prior to that he served as CEO and managing director. In 2006, he was given the Padma Bhushan, one of the highest civilian honors awarded by the government of India. He received his bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering from the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Bombay, in 1978.

S. Gopalakrishnan, founder, CEO, and managing director. S. Gopalakrishnan has been serving as CEO of Infosys since 2007. He is currently the chairman of the Indian Institute of Information Technology and Management (IIITM), Kerala. He holds MS (physics) and MTech (computer science) degrees from the Indian Institute of Technology, Madras.

S. D. Shibulal, founder, COO, and member of the board. S. D. Shibulal has been serving as chief operating officer since 2007. Prior to that, he served as group head of worldwide sales and customer delivery. He received a master’s degree in physics from the University of Kerala and an MS in computer science from Boston University.

K. Dinesh, founder and member of the board. K. Dinesh is head of quality, information systems, and the communication design group. He completed his postgraduate degree in mathematics from Bangalore University and was awarded a doctorate in literature by the Karnataka State Open University in 2006.

T. V. Mohandas Pai, member of the board and director of human resources. T. V. Mohandas Pai joined Infosys in 1994 and has served as a member of the board since 2000. He leads efforts in the areas of human resources, education, and research. He holds a bachelor’s degree in commerce from St. Joseph’s College, Bangalore, and a bachelor’s degree in law from Bangalore University, and is a Fellow Chartered Accountant (FCA).

Srinath Batni, member of the board. Srinath Batni joined the board in 2000 and is responsible for delivery excellence across the company. He received a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Mysore in 1975 and a master’s degree in mechanical engineering from the Indian Institute of Science in 1979.

INDEPENDENT NONEXECUTIVE DIRECTORS

Rama Bijapurkar. Rama Bijapurkar has worked at McKinsey & Company, MARG Marketing & Research Group, Hindustan Unilever, and MODE Services. She is recognized for her expertise in market strategy and consumer issues. An alumna of the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, she is also a visiting professor at her alma mater and serves on its board of governors.

David L. Boyles. David Boyles built a career in senior leadership positions at large multinational corporations including

American Express, Bank of America, and Australia and New Zealand Banking Group (ANZ). Boyles earned an MBA degree from Washington State University and an MA and a BA in psychology from the University of Northern Colorado at Greeley.

Omkar Goswami. Omkar Goswami is the founder and chairman of CERG (Corporate and Economic Research Group) Advisory Ltd. From 1998 to 2004, he served as chief economist of the Confederation of Indian Industry. He received his master’s degree in economics from the Delhi School of Economics in 1978 and earned his PhD from Oxford in 1982.

Sridar A. Iyengar. Sridar Iyengar previously was a senior partner with KPMG in the United States and U.K. and served for three years as chairman and CEO of KPMG’s operations in India. He has served as an adviser to several venture and private equity funds with an interest in India. Iyengar has a Bachelor of Commerce degree from the University of Calcutta and is a fellow of the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales.

Jeffrey Sean Lehman. Jeffrey Lehman is professor of law and former president of Cornell University. He is currently a senior scholar at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C. At one point he served as a law clerk for John Paul Stevens of the U.S. Supreme Court. Lehman earned an AB in mathematics from Cornell University and Master of Public Policy (MPP) and JD degrees from the University of Michigan

Deepak M. Satwalekar, lead director. Deepak Satwalekar has been the managing director and CEO of HDFC Standard Life Insurance Company Ltd. since 2000. He has been a consultant to the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank, and the U.S. Agency for International Development. He holds a bachelor’s degree in technology from IIT, Bombay, and a master’s degree in business administration from The American University in Washington, D.C.

Claude Smadja. Claude Smadja is the president of Smadja & Associates, a strategic advisory firm he founded in 2001.

He joined the World Economic Forum in 1987 as a director and member of the executive board. He is a graduate of the University of Lausanne, Switzerland, and serves on the International Board of Overseers of the Illinois Institute of Technology.

Marti G. Subrahmanyam. Marti Subrahmanyam is the Charles E. Merrill Professor of Finance, Economics, and International Business in the Stern School of Business at New York University. He serves as an adviser to international and government organizations, including the Securities and Exchange Board of India. He holds degrees from the Indian Institute of Technology, Madras; the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad; and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Source: Infosys Technologies Ltd., Members of the Board, 2009, http://www.infosys.com/about/management-profiles/default.asp.

As the box, “Infosys Technologies Board of Directors, 2009,” shows, five of seven of the executive directors are also cofounders of the company, and two are former chief executives, a practice not well received in the rules-based governance model but ideal from the values-based standpoint because they bring the personal commitments to company values that one expects in founders. Murthy reported that the board’s original design and its many decisions since then have followed the same set of principles that he and his cofounders had used in creating the company to begin with, including the following:

- The softest pillow is a clear conscience.

- When in doubt, disclose.

- Don’t use corporate resources for personal benefit.

- Put long-term interests ahead of short-term ones.

- A small slice of a large pie is better than a large slice of a small pie: the company’s growth depends on management’s sharing profits with all employees.30

The Distinctiveness of Indian Governance

As with human resource decisions, company leadership, and competitive strategy, so with corporate governance. India’s top executives follow a path similar to, yet different from, that of their counterparts in the United States and other countries. Indeed, Dale Berra’s “our similarities are different” might serve as a mantra for the entire U.S.–India business interface.

Among the more notable differences are a stronger sense of social mission, a weaker commitment to investors—especially in responding to their short-term demands—and a higher value on employees and culture. In looking upon their company’s governance, these executives put values at the forefront, with a shared sense of social responsibility that calls for incorporating the interests of all the firm’s stakeholders. The role of family-promoted business groups is particularly distinctive. Those who lead them combine the roles of primary owner, company leader, and prominent citizen, and their firms and their social outreach have served as models for new companies and aspiring leaders.

We can see here an important source of two principal practices of the India Way: the focus on broad mission and purpose, and the holistic engagement with employees. With a greater relative emphasis on values-based governance, Indian business leaders have been less constrained by investor insistence on steadily increasing shareholder value. Greater executive attention thus can be devoted to their company’s contributions to the community and the country, not just their investor returns, and to building their workforce, not just cutting labor costs.

Encouraged by both international investors and the Securities and Exchange Board of India, many Indian firms in recent years have accepted the rules-based model so prevalent in the United States, and with good and practical cause. An early-2000s study found that development financial institutions lent more and mutual funds invested more in companies well governed by SEBI standards.31 Yet at the same time, these firms have also embraced the values-based model that has emerged indigenously within India. As the case of Infosys Technologies shows, the two models are not mutually exclusive and indeed should be seen as compatible.

To be sure, adopting the values-based approach without the accompanying discipline of a rules-based model runs the risk of improper management exploitation of shareholders other than the founding family or the primary owner—the temptation, say, to “tunnel,” or transfer cash among companies to prop up a languishing firm within a business group. As in the U.S. and other economies, Indian business can make no claim to being malfeasance-free. But the leaders interviewed for this project make a persuasive case for viewing good corporate governance as a healthy balance of rules-based and values-based principles—a model of India’s own making.