CHAPTER ONE

Indian Business Rising

The Contemporary Indian Way of Conducting Business

AT 9:20 P. M. on Wednesday, November 26, 2008, ten terrorists launched a shockingly violent attack on India’s main business center, targeting a hospital, restaurant, railway station, Jewish center, and two luxury hotels, all in Mumbai. As the world watched in horror on live television, bystanders ducked bullets, and flames devoured a landmark. The three-day rampage—what some have termed India’s “26/11”—ended with the death of more than 170 people, including 28 foreigners, the chief of Mumbai’s antiterrorist squad, and the chairman of Yes Bank.

We watched these events unfolding with special interest. Our ties to India and the Indian business community ran deep, our concerns were many, and we were, after all, in the midst of writing a book about the Indian business juggernaut. But we had a more immediate concern, too. One of India’s most prominent business leaders, Anil D. Ambani, executive chairman of Reliance ADA Enterprises, was scheduled to address a ceremony at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School on Monday, December 1, only days after the attack ended. The occasion was the dedication of a lecture hall to his late father, who had founded a company that Anil Ambani and his brother, Mukesh, had now transformed into two of India’s largest conglomerates.1 Would he be able to make the dedication?

In fact, the ceremony had to be deferred, but the delay came not because Anil Ambani’s firm had been significantly affected. Rather, the country’s prime minister, Manmohan Singh, asked him to remain in India to serve, in the words of our dean’s announcement of the postponement, “as a visible beacon of national stability.” Anil Ambani heeded the call, and in a well-publicized event, the veteran marathoner jogged with several friends near a scene of the carnage just hours after it had been secured, in what one newspaper termed “a symbolic display of the resilience for which Mumbai is widely admired.”2

In America, the financial crisis of 2008–2009 had shattered public confidence in corporate leaders ranging from the executives of Lehman Brothers and Fannie Mae to those of Merrill Lynch and General Motors, a confidence already weakened by bonus payments, company jets, and golden parachutes. Financial institutions were reeling, factories were shuttering, unemployment was climbing to levels unseen in most lifetimes. Far from being able to claim a mantle of national leadership, U.S. executives had plummeted in virtually every measure of public esteem.

In India, by contrast, big business leaders had come to be emblematic of national achievement and fortitude. Firms that had been the scene of horrible events were springing back to life in time frames almost unthinkable by post-9/11 standards. The Taj Mahal Hotel, devastated by the attacks, needed only three weeks to reopen for business. And the world had taken notice. When Hillary Clinton visited India a half year after the terrorist attack, the U.S. secretary of state began her stay in Mumbai, the country’s business capital, not New Delhi, its political capital. Taking up residence in the by then fully restored Taj Mahal Hotel, she opted to meet first with Indian business leaders, including Mukesh Ambani, executive chairman of Reliance Industries, and Ratan Tata, head of the $62 billion Tata Group.

“India’s booming economy has turned some business executives into rock stars,” the New York Times correspondent wrote of the meeting, and it was thus “not surprising” that the secretary of state “would stop first in India’s commercial capital for a power breakfast with bankers and billionaires.”3

Mukesh Ambani, whose estimated personal wealth exceeded $19 billion at the time of the meeting, told Hillary Clinton of the need for technological innovation to curb emissions, a creative solution to an emerging tension between developed and developing nations. Ratan Tata, whose companies are ubiquitous throughout the subcontinent, explained to the American emissary how his enterprise was providing nutrients to children across India through the enriched milk it delivers.

This melding of business and national leadership is central to the Indian way of doing business. Many business leaders are deeply involved in societal issues, and they deem it entirely appropriate—even requisite—to voice their views on subjects ranging from climate change to child nutrition. Some of this has to do with the imperatives of development: many Indian firms believe that national growth is essential for their own profitable expansion. Some derives from a long-standing tradition of business largesse, with many companies committed to social goals through philanthropic giving and infrastructure investing near production facilities. Yet the melding goes well beyond private profits and public charity, with national purpose as much a part of the business mind-set as financial results and reputational gain.

This mind-set can be seen in the willingness of the cochairman and former chief executive of Infosys Technologies, Nandan Nilekani, to accept the call to direct India’s mammoth national effort to provide a unique digital identification number to all of its 1.1 billion citizens, deemed essential for effective delivery of social services across the country.4 It is found in the personnel mantra at HCL, the fast-growing international IT service firm: “Employee First, Customer Second.”

Principal Practices of the India Way

- Holistic engagement with employees. Indian business leaders see their firms as organic enterprises where sustaining employee morale and building company culture are treated as critical obligations and foundations of their success. People are viewed as assets to be developed, not costs to be reduced; as sources of creative ideas and pragmatic solutions; and as bringing leadership at their own level to the company. Creating ever-stronger capabilities in the workforce is a driving objective.

- Improvisation and adaptability. Improvisation is also at the heart of the India Way. In a complex, often volatile environment with few resources and much red tape, business leaders have learned to rely on their wits to circumvent the innumerable hurdles they recurrently confront. Sometimes peppering English-language conversations, the Hindi term jugaad captures much of the mind-set. Anyone who has seen outdated equipment nursed along a generation past its expected lifetime with retrofitted spare parts and jerry-rigged solutions has witnessed jugaad in action. Adaptability is crucial as well, and it too is frequently referenced in an English-Hindi hybrid, adjust kar lenge—“we will adjust or accommodate.”

- Creative value propositions. Given the large and intensely competitive domestic market with discerning and value-conscious customers, most of modest means, Indian business leaders have of necessity learned to be highly creative in developing their value propositions. Though steeped in an ancient culture, Indian business leaders are inventing entirely new product and service concepts to satisfy the needs of demanding consumers and to do so with extreme efficiency.

- Broad mission and purpose. Indian business leaders place special emphasis on personal values, a vision of growth, and strategic thinking. Besides servicing the needs of their stockholders—a necessity of CEOs everywhere—Indian business leaders stress broader societal purpose. The leaders of Indian business take pride in enterprise success—but also in family prosperity, regional advancement, and national renaissance.

The mind-set is embedded in Hindustan Unilever’s Project Shakti, which has used the principles of microfinance to create a sales force in some of the subcontinent’s most remote regions. It reveals itself in community hospitals and grade schools and virtual universities built across the country by name-brand businesses. Most significant, what we have come to term the India Way expresses itself in an economy that even in perilous global times remains a dynamo, driven by big companies bent on growing at prodigious rates and competing globally.

The India Way

The India Way comprises a mix of organizational capabilities, managerial practices, and distinctive aspects of company cultures that set Indian enterprises apart from firms in other countries. The India Way is characterized by four principal practices: holistic employee engagement, improvisation and adaptability of managers, creative value delivery to customers, and a sense of broad mission and purpose (see “Principal Practices of the India Way”).

Bundled together, these principles constitute a distinctly Indian way of conducting business, one that contrasts with combinations found in other countries, especially the United States, where the blend is centered more around delivering shareholder value. Indian business leaders as a group place greater stress on social purpose and transcendent mission, and they do so by devoting special attention to surmounting innumerable barriers with creative solutions and a prepared and eager workforce.

Purpose, pragmatism, and people aptly capture much of the essence of the India Way, but allow us to stress at the outset that we are writing about generalized qualities. To travel any distance in India is to experience firsthand the maddening bureaucratic delays that remain an endemic though diminishing part of everyday Indian life. Nor do Indian firms and their leaders have a monopoly on virtue. Corruption and malfeasance can be found in the Indian business community as surely they can be found in all business communities. Note, for instance, the scandal involving Satyam Computers and its CEO, Ramalinga Raju, who sits in an Indian jail as we write.

Not all Indian business leaders, in short, are saints or sages, just as not all American CEOs are focused laserlike on delivering shareholder value while ignoring larger societal concerns. That said, the attributes of the India Way we describe in these pages appear often enough and especially among the most successful companies that they have come, we believe, to constitute a clear and distinctive model. Drawn from the voices of Indian business leaders, and from our observations of Indian leaders and companies in action, the set of four attributes above captures much of the modern Indian way of conducting business.

Why It Matters

When Westerners think of India, names like Bajaj Auto and Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories are hardly the first to come to mind. The Taj Mahal’s beauty and Calcutta’s squalor are far more defining, with the vale of Kashmir and bustling bazaars of Chandni Chowk in New Delhi not far behind.

Yet increasingly, India is also a world leader in business, with everything from medical procedures to investment banking either migrating from the United States and elsewhere to India or springing up from within. Simultaneously, Reliance, ICICI, Infosys, and hundreds of India’s other top companies have been clambering onto the world stage to compete directly against Western multinationals in virtually all sectors. In mastering the art of high-quality and efficient production—and in developing unique ways of managing people and assets to achieve it—Indian executives have delivered growth rates that would be the envy of any Western executive. During much of the 2000s, India’s gross domestic product (GDP) had been rising by better than 9 percent per year—several times that of the United States and nearly that of China. That 9 percent–plus GDP growth, we should note, represents Indian businesses as a whole (additional indicators of India’s fast growth can be found in appendix A). Many of the nation’s premier companies—the focus of our inquiry—reported that they were growing at twice the rate of the general economy, or more. Chairman Subhash Chandra of Zee Entertainment Enterprises—India’s largest media and entertainment company—told us, for instance, that his company had grown from $400 million in annual revenue six years earlier to $2 billion at the time of our interview with him. Managing director G. R. Gopinath of Deccan Aviation said before his acquisition by Kingfisher Airlines in 2007 that he had been adding a new aircraft every month to the fleet, growing from one to forty-five planes in less than four years. Infosys Technologies’ chairman Narayana Murthy had presided over a company that employed 10,700 and drew $545 million in revenue in 2002; seven years later, his company employed 104,900 and earned revenue of $4.6 billion.

We have come to believe that undergirding the rapid expansion of the Indian economy—and above all the stunning growth of its largest companies—is an innovative and exportable way of doing business, but we did not approach this project with that conclusion in mind. In fact, we had expected much the opposite: with the triumph of American-style capitalism, at least until it came under a cloud during the financial crisis of 2008–2009, managers around the world had often sought to understand the leadership secrets of U.S. companies like Apple Computer and General Electric. In commencing our study of Indian business leaders, we had anticipated a cross-national convergence on American terms, with Indian companies looking to adopt the management methods of Steve Jobs, Jack Welch, and other leaders of American enterprise.

What we found instead was a mantra of “not invented there.” Though well aware of Western methods, Indian business leaders have been blazing much their own path. And though rooted in the traditions and times of the subcontinent, the value of their distinctive path can, we believe, transcend the milieu from which it arose. When Indian companies, for instance, take over publicly traded American firms—such as Tata Motors’ acquisition of Ford’s Jaguar and Land Rover divisions in 2008—research confirms that the acquired firms increased both their efficiency and their profitability.5 Rather than appreciating the value of the India Way only upon acquisition, Western firms might be well advised to learn from the Indian experience in advance. Indeed, we believe that understanding the India Way and its drivers has become vital for business managers everywhere.6

In completing this study of Indian business leaders, we were repeatedly reminded of the remarkable impact that Japanese business leaders and the Toyota Way have had on the auto-making world and far beyond. The methods of lean production pioneered by Eiji Toyoda and his company—treating all buffers as waste and seeking continuous improvement in all aspects of production—originated in the cultural traditions and austere times of postwar Japan. But the methods have proved powerful drivers far beyond that context, enhancing both quality and productivity in everything from Porsche manufacturing in Germany to hospital processing in the United States.7 With a model originally built in Japan, Toyota has become the world’s largest automaker, and its methods have come to be widely emulated by managers far beyond Japan.

Much the same applies to the India Way. It was born of the circumstances facing Indian business during the past two decades, but like the Toyota Way, it is also a model that can readily transcend its origins, providing a template for Western business leaders to reinvigorate their own, often sluggish growth rates. Think of it pragmatically: if applying the principles of the India Way were to generate even a single extra percentage point in yearly growth—say, increasing the annual growth rate from 3 to 4 percent—over the next five years, the 4 percent–rate companies would see their value doubled, compared to 3 percent–rate firms. Over ten years, they would triple their worth, compared to the slower-growing companies.

Who We Interviewed

India is a vast economy with a wide variety of practices and arrangements across its more than seven hundred thousand companies. To understand the company capabilities and leadership capacities that have constituted a vital factor in the nation’s growth, we focused on the country’s largest firms—those that have played a leading role in India’s rapid development and have come to serve as models of business enterprise for entrepreneurs and managers throughout the nation. Our approach has been to interview those at the top of the pyramid, the leaders of India’s largest firms. That is where the critical decisions of the nation’s most important companies are made, particularly those strategic choices that have helped define India’s distinctive approach to business.

We approached a hundred fifty of the largest publicly listed companies by market capitalization, and we secured time with more than one hundred of their executives. We asked what leadership qualities they saw as most vital to their success. We probed how they worked with their boards of directors, what their directors brought to the table, and where they saw convergence with or divergence from Western practices. We inquired about their methods for recruiting talent and managing teams, and asked what lasting legacies they hoped to leave behind when they stepped down one day from their executive suites.

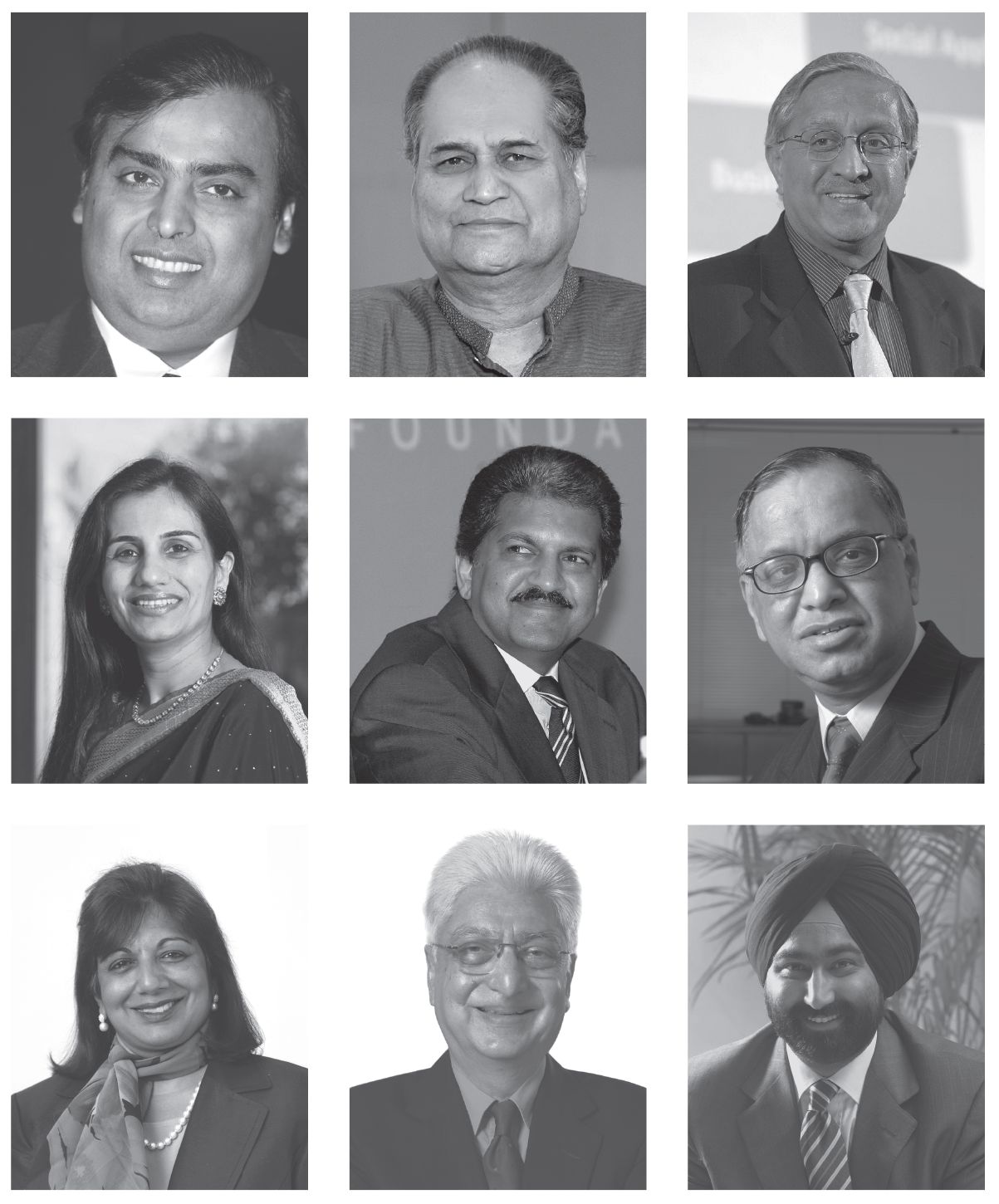

We cast our net broadly, interviewing executives who produced steel, managed airlines, and manufactured pharmaceuticals; those who were entirely self-made, the Horatio Algers of Indian business; and those whose company fortunes were inherited, the Fords and Rockefellers of Indian dynasties. Among those we interviewed are Reliance Industries chief executive Mukesh Ambani, ICICI Bank CEO Chanda Kochhar, Bajaj Auto chairman Rahul Bajaj, Infosys Technologies chairman Narayana Murthy, and even the former and now disgraced and imprisoned Satyam CEO, Ramalinga Raju. We have sought to let Indian business leaders speak for themselves, to characterize their leadership experience and philosophy in their own words as very well-placed participant-observers. All are immersed in the phenomenon in ways that outside observers can never be. Nine of those who are living and defining the India Way—its active proponents and daily reinventors—are displayed in figure 1-1, and the others are described in appendix B.8

“We Think in English and Act in Indian”

The essence of the India Way is embodied in the thinking and perceptions of the business leaders themselves. We “think in English and act in Indian,” observed R. Gopalakrishnan, the executive director of Tata Sons, the holding company of the Tata Group, a set of companies dating back to 1868—some ninety-eight enterprises in all, employing 290,000 and booking annual revenue equal to 3.2 percent of the nation’s GDP. By comparison, Wal-Mart Stores, America’s largest company with more than 2 million employees, drew annual revenue in 2007 equivalent to 2.7 percent of the U.S. GDP.

“For the Indian manager,” Gopalakrishnan explained, “his intellectual tradition, his y-axis, is Anglo-American, and his action vector, his x-axis, is in the Indian ethos. Many foreigners come to India, they talk to Indian managers, and they find them very articulate, very analytical, very smart, very intelligent—and then they can’t for the life of them figure out why the Indian manager can’t do what is prescribed by the analysis.”

Business leaders living and defining the India Way

Indian business leaders (left to right, top to bottom): Mukesh D. Ambani, managing director of Reliance Industries; Rahul Bajaj, executive chairman of the Bajaj Group of companies; R. Gopalakrishnan, executive director of Tata Sons; Chanda Kochhar, CEO and managing director of ICICI Bank; Anand Mahindra, vice chairman and managing director of Mahindra & Mahindra; N. R. Narayana Murthy, the joint chairman and chief mentor of Infosys Technologies; Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw, executive chairman and managing director of Biocon; Azim Premji, chairman of Wipro; and Malvinder Mohan Singh, managing director and CEO of Ranbaxy Laboratories

Sources: Ambani—The India Today Group/Getty Images; Bajaj—Bajaj Auto India; Gopalakrishnan—Tata Sons Ltd.; Kochhar—ICICI Bank India; Mahindra—AFP/Getty Images; Murthy—The India Today Group/Getty Images; Mazumdar-Shaw—Biocon Ltd.; Premji—Wipro Technologies; Singh—Religare Enterprises/Fortis Healthcare. Used with permission.

Compared with the West, he said, Indian executives are more respectful of seniority, government, and tradition. They rely more upon their intuition than their Western counterparts. Viewpoints are indirectly expressed; silence is sometimes golden. A European executive who had recently met with the Indian prime minister marveled at how quiet the nation’s leader was—but also how powerful his words were when finally spoken. Compare that to the clamor of a gathering of the Business Roundtable—the lobbying arm for the chief executives of America’s largest corporations—and you’ll have some idea of how different “acting in Indian” can be.

The emergent Indian model revolves around basic questions that all companies face whatever the national setting: How can they best compete? What steps are required to prosper in a highly competitive marketplace? Are there sustainable advantages? Such questions go to the very heart of business strategy and often evoke similar responses from business leaders almost everywhere.

One of the distinguishing aspects of the India Way, however, has been the capacity of the nation’s business leaders to find a creative advantage where no one else was looking. They have often built and followed structures and strategies radically different from the Western norm, though the practices that have flowed from those decisions have frequently proved applicable to business in other markets, including the United States, even if the applicability has not yet been widely recognized. The Tata Nano, the pint-size car built by Tata Motors—India’s largest maker of automobiles and trucks, with 60 percent of the market—is a case in point. In its development can be seen the defining themes of acting in Indian.

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, U.S. car makers, the global industry’s most established incumbents, directed their attention to trucks and sport-utility vehicles (SUVs), and indeed, the best-selling vehicles for American companies for many years were full-size trucks, not cars. This strategic focus derived from sophisticated business analysis driven by marketing information on both consumers and competitors. Market analysis had revealed less immediate competition in the truck and SUV segments than in conventional cars since Japanese auto producers, the most important foreign makers in the American market, were still working their way up the value chain from autos to trucks. Producing trucks and SUVs was thus a market segment that offered the opportunity for the greatest immediate profit margins.

At the same time, Tata Motors was moving in the opposite direction, pushing ever deeper into its traditional market segment of small inexpensive cars. This is the most competitive, lowest-profit-per-car segment in the world auto industry, one that runs up directly against the strongest Japanese competitors. Still, Tata Motors decided to stay with its existing customer base. Realizing that India’s mass market hungered for even lower-cost transportation, Tata set out to engineer an automobile whose price would be not just marginally lower than the lowest-end existing products but radically lower, not 10 percent but 75 percent below the lowest-end. Tata Motors knew that it would have to do the engineering largely on its own, without the benefit of the research and development that one might find in universities and government laboratories in other countries. It knew, too, that, like all its products, the Nano would have to be developed on a shorter life cycle. “We can’t have forty-eight or thirty-six months to bring out the new products,” offered Tata Motors executive director for finance Praveen Kadle; now it’s just “twenty-four or eighteen months.”

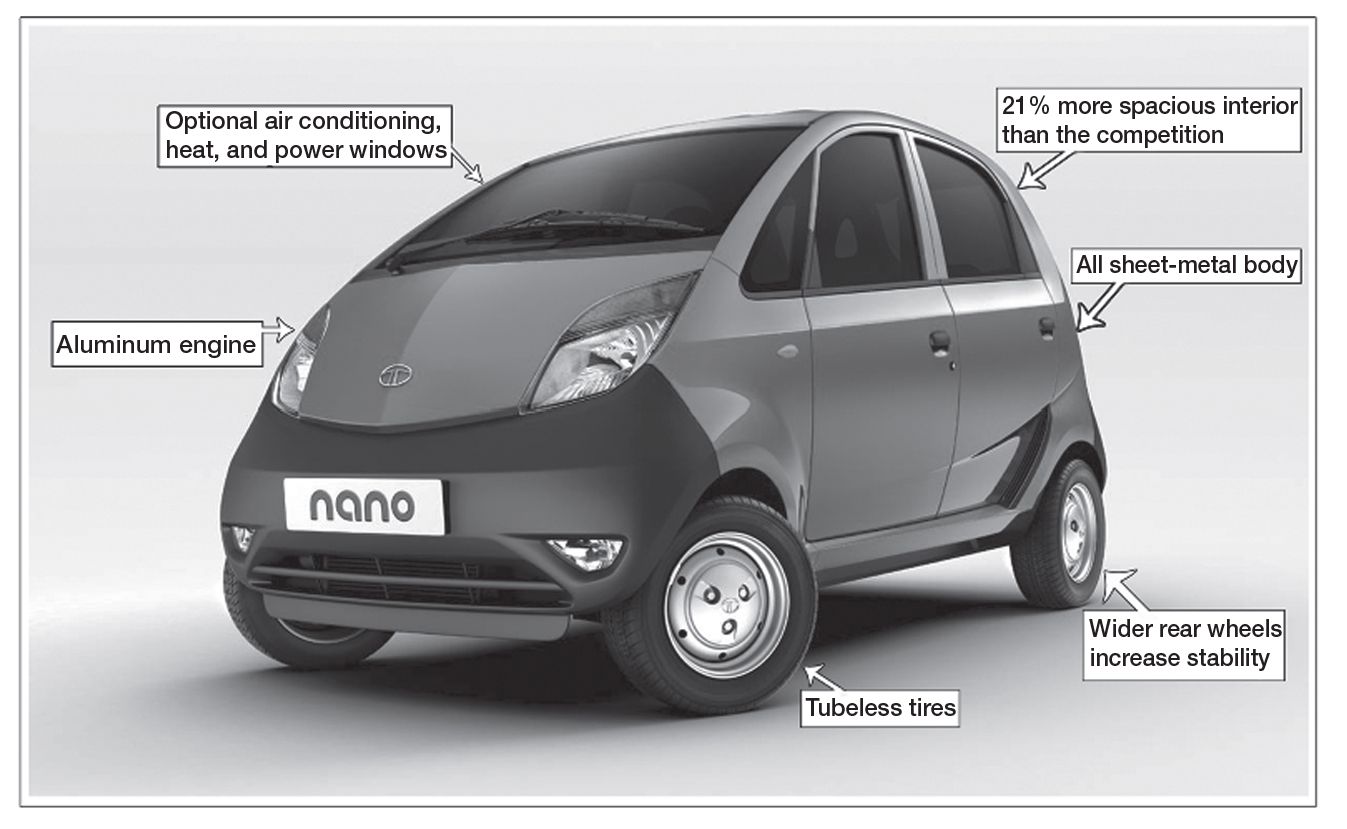

With all that in mind, Tata Motors swiftly designed the Nano from a clean sheet of paper to meet what appeared to be an impossibly low price point: 100,000 rupees per car, about $2,500 at the time. The sticker price of the Nano, presented as the world’s most inexpensive car when unveiled in January 2008 by Ratan Tata, chairman of the Tata Group, was to be on a par with the cost of a DVD option in luxury Western autos.9 (See figure 1-2.)

How could Tata sell the Nano at less than half the price of its closest competitor in India, the Maruti 800? The answer was not in any radical technological innovation, but in a completely new design based on what some analysts have dubbed Gandhian engineering principles—deep frugality and a willingness to challenge conventional wisdom—and a single-minded determination by Tata’s top managers to work through the many constraints and challenges of operating in the Indian environment. They designed everything in the Nano from scratch, and they deleted many features that were taken for granted by car makers, including air-conditioning, power brakes, and radios. Although the Nano is smaller in size than the Maruti 800, it offers some 20 percent more seating capacity as a result of an intelligent design that moved the wheels to the extreme edges of the car. By using an aluminum engine and lightweight steel, the designers were able to build a car that was significantly lighter than anything else on the road with four wheels and could achieve a fuel efficiency of 50 miles to the gallon.

The Tata Nano

Source: Tata Motors Corporate Communications/Wharton. Used with permission.

The Nano’s other important feature is its modular design. Kits of components are to be sold en masse for assemblage and distribution by local businesses. Ratan Tata has talked about “creating entrepreneurs across the country that would produce the car.” That, he said, is “my idea of dispersing wealth.”10 Tata even anticipated providing the tools for local mechanics to assemble the car in existing auto shops or new garages created to cater to rural customers. Termed open distribution innovation by BusinessWeek, the method could create not only the world’s least expensive automobile but also its largest-selling one. For proponents of the “bottom of the pyramid” approach who stress the importance of developing innovative models to tap the vast potential of the lower end of emerging markets, the Nano would seem to be the answer to a prayer: a cheap but sturdy product that could spawn a whole network of support businesses.

To be sure, production and distribution of the Tata Nano ran up against a host of constraints and challenges, from safety concerns (readying the car to meet British standards, for example, would double the price) to environmental and political ones: in October 2008, violent protests forced Tata Motors to abandon a controversial production site in the Indian state of West Bengal. Add to those problems the economic woes emanating from a global financial crisis, and realizing the Nano’s full potential will depend much upon the continuing resilience and tenacity of Tata’s top management—but, of course, those are the very skills that brought the car into existence in the first place.11

Ratan Tata created an entirely new class of car targeted at the great multitude of Indians who could not afford to buy a conventionally conceived automobile. Getting there was a matter of “pushing the organization to think very differently,” said Satish Pradhan, executive vice president for group human resources at Tata Sons. The class of car also targeted the competition. “Tata Motors has built up a position,” said Gopalakrishnan, “where international car companies are not able to compete with us.” And that, in essence, is a large part of what the India Way is all about: a strategy of focusing the energy and attention of company managers on the hard and persistent needs of their customers, achieving outcomes that break through traditional standards of products and services.

The Promise of the Book

The insights offered by our diverse group of Indian business leaders is the spine of this book and the foundation for our fleshing out of the India Way. We have added our own voices as well, our own interpretation of what they collectively said and implied. The four of us, all colleagues at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, have long studied U.S. companies and managers, authoring a range of articles and books on American business and its leaders. But two of us also grew up and studied in India; a third spent the better part of two childhood years there; and all of us have frequently traveled to India for teaching, research, consulting, board meetings, and family visits. With this dual heritage, we have drawn on our joint experience to examine what is unique about Indian business leadership and to better understand what can be usefully learned by Western managers and executives.12

As directors of three Wharton research centers—the Mack Center for Technological Innovation, the Center for Human Resources, and the Center for Leadership and Change Management—we have also drawn upon diverse information networks and funding sources in preparing this account. In collaboration with the National Human Resource Development Network, India’s premier human resource organization, we gained ready access to the highest circles of Indian business. And as faculty members, we have extensive contacts with the companies and executives that are at the heart of the India Way. We are also personally familiar with a broad array of American, European, Latin, and Asian companies and executives that serve as useful points of comparison. In building our portrait, we have drawn as well on a host of academic and industry studies of Indian business leadership. Our project was facilitated by India’s long-standing democratic and Anglo traditions that make the experience of Indian business leaders exceptionally accessible and applicable to Western management.13

If business leadership around the world is converging, we have concluded, it may come to be as much on Indian terms as on those from the West. Company managers everywhere can usefully learn from India’s example the power of cause, culture, and consultation; the advantage of creative value propositions and rapid decision making; the value of employees as assets instead of liabilities; the utility of building for the era, not only the quarter; the benefit of company loyalty over shareholder value; and the advantage of national mission over private purpose.

The principles are not so unique to the Indian context that they could work only there. Simply put, if Indian business leaders can build their distinctive methods so rapidly, over just the past two decades, and if they can learn to manage diversity so effectively in one of the world’s most complexly diverse societies, other business leaders in other countries can surely do so as well. The model in the pages that follow is there and waiting. We begin with the nation’s decision in the early 1990s to liberalize the economy and dismantle the license raj, a foundation for so much that has emerged. We then turn to the principles by which Indian business executives manage their people, lead their firms, define their culture, create their value propositions, and draw upon their governing boards.

Whether it is a good moment to invest in the subcontinent, we leave to those more versed in the ways (and caprices) of financial markets. What we do believe wholeheartedly is that the time is both ripe and right to better understand what is driving the Indian economic powerhouse: that blending of practices we call the India Way.