CHAPTER FOUR

Leading the Enterprise

Improvisation and Adaptability

IF PEOPLE MANAGEMENT constitutes a defining quality of the India Way, so too does a distinctive style of executive leadership. The unique approach derives from the India Way’s emphasis on broad mission and purpose, and it builds on the stress on improvisation and adaptability. Business leaders think broadly and act pragmatically, setting grand agendas and then testing through trial and error what works and what does not. While that approach has served Indian business leaders well, the global business community has remained remarkably unaware of its impact and unfamiliar with its most noted practitioners.

This was evident by exception in 2001, when on a balmy May afternoon in West Philadelphia, roughly one thousand MBA students assembled to hear a groundbreaking commencement address. For the first time in the Wharton School’s 120-year history, the graduation speaker—by overwhelming student demand—was the chief executive of an Indian company, N. R. Narayana Murthy of Infosys Technologies. Just six years later, this once rarest of scenarios would repeat itself, this time with Lakshmi Mittal, the chairman and chief executive of the world’s largest steel company, ArcelorMittal, addressing Wharton’s 2007 MBA class.

For years, Indian executives had attended American business schools. Mukesh Ambani of Reliance Industries and Anil Ambani of Reliance ADA Enterprises graduated from Stanford and Wharton, respectively. Adi Godrej of the Godrej Group graduated from MIT’s Sloan School of Management, while Rahul Bajaj—head of India’s largest maker of scooters, rickshaws, and three-wheelers—and Palaniappan Chidambaram, Indian home minister in 2009 and formerly finance minister, both earned MBAs at Harvard. Even those Indian leaders who did not attend American universities still studied the world’s best practices—multidivisional management, process reengineering, and flexible manufacturing—commonly taught and developed at U.S. business schools. ICICI’s K. V. Kamath, for example, learned U.S.—as well as Japanese and European—management techniques while at the Asian Development Bank in Singapore.

Why then—given the deep familiarity of Indian business leaders with U.S. management precepts, the growing Indian student presence at American business schools, and the explosive Indian economy—was it so rare to find a Murthy or a Mittal at the commencement lectern in the United States, until recently? That answer reflects a larger ideological battle—one that heavily favored American executives.

The Indian Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism

The relationship between capitalism and the power of ideas was most famously addressed in Max Weber’s The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Weber presented a compelling argument that the fuel of northern European capitalism came not from the magic of markets but from the religious ideology specific to that region. In Weber’s telling, Protestantism prescribed that individuals should accumulate and reinvest in their material creation, generating what might now be called a “powerful synergy” between ideas—religious ethics—and capitalist growth.

Later, Weber’s intellectual disciples Reinhard Bendix and Mauro Guillén offered kindred explanations for the drivers of executive behavior. In their respective books, Work and Authority in Industry and Models of Management, they argued the case for seeing business practices as a product of managerial ideologies, not just organizational necessities. Together, Weber and his academic progeny continue to remind us of the supremacy of ideas, even when we are engaged in the most material of human endeavors: building private enterprise.1

In recent years, the most popular and influential of these books have largely focused on American executives and their management techniques. Just as Indian business leaders were largely overlooked as graduation speakers, they did not author popular books on what constitutes good private enterprise leadership. Instead, those ideas largely came from the pinnacles of U.S. business experience—the titans who transformed fledgling enterprises into American powerhouses.

Early accounts by Alfred P. Sloan of his years at General Motors and AT&T’s Chester I. Barnard defined how executives around the world thought of themselves. In more recent years, the chronicles of Lee Iacocca at Chrysler and Jack Welch at General Electric had become exemplary accounts for many managers as well. So, too, had Thomas Peters and Robert Waterman’s In Search of Excellence, Jim Collins and Jerry Porras’s Built to Last, and Jim Collins’s Good to Great.2

For decades, Indians have been among the most avid readers of these books. Jack and Suzy Welch’s Winning spent months on the Times of India’s business best-seller list and, for a time, was generally available in the country’s business centers. Caught by a Mumbai traffic light, waiting drivers were often surrounded by street vendors with fresh pineapples, cheap umbrellas, and Jack Welch’s books.

For all its intensity, though, this flow of ideas has tended to be a one-way conversation. Even as Indian business continued to compete successfully on the world stage, there was very little recounting of Indian managerial models. One exception was C. K. Prahalad’s The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid, showing that there was a large, untapped opportunity in servicing low-income consumers in India and that emergent business models for doing so had much to offer managers from the West.3 Yet in mid-2008, the Wall Street Journal listed no best sellers on Indian business; all its titles focused on U.S. enterprise. Even more surprisingly, the Business Standard, India’s equivalent to the Wall Street Journal, reported that the ten best-selling business books during the same time period included eight on American business or by U.S.-based authors, including Sloan’s My Years with General Motors, first published in 1964, and Peter Drucker’s People and Performance. Only one Indian title, Business Mantras by Radhika Piramal et al., made the list.4

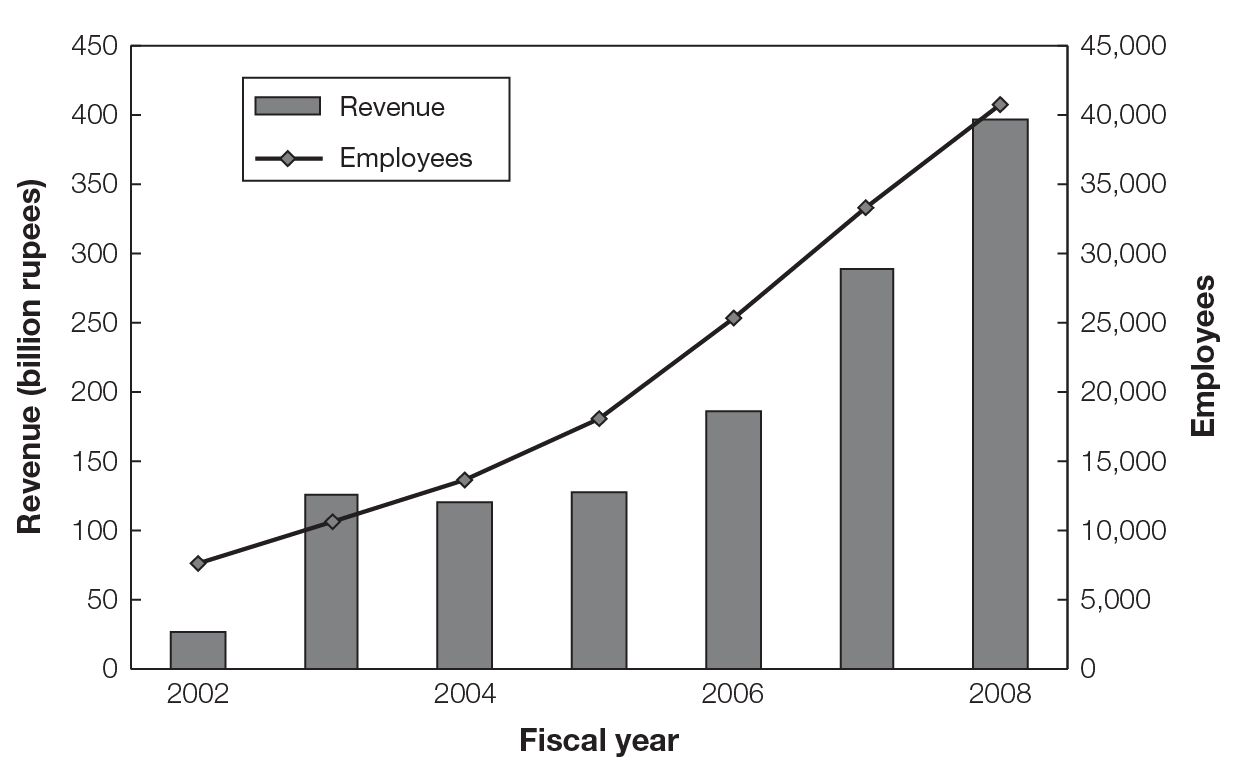

The overwhelming influence of U.S. business leadership and precepts could be seen in the number of foreign students seeking to enter American MBA programs. From a steady trickle in previous years, foreign admissions had grown to a torrent in the late 2000s, with Indian students leading the way. Just eleven Indian students finished the Wharton MBA program in 1990; by 2008, that number had grown tenfold, well ahead of China or any other nation (see figure 4-1).5

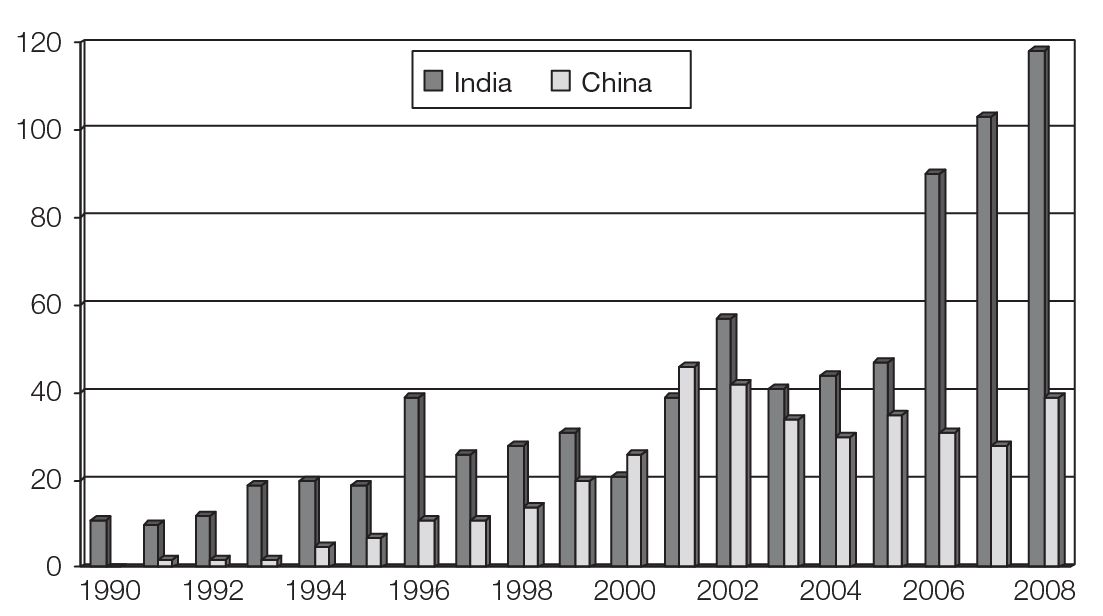

The number of Graduate Management Admission Tests taken during the 2000s, a necessary step for entry to most American MBA programs, showed the same pitched trend. GMAT test taking rose during the decade by 74 percent in Asia, by 161 percent in China, and by 341 percent in India (see figure 4-2). Not all of the test takers were heading for American business schools, but they were submitting 70 percent of their test scores to U.S. programs.6

Different Similarities

Given these trends, it comes as no surprise that many principles of business leadership are virtually identical in both the United States and India, and indeed are valued in virtually all countries.7 Managers worldwide are looking to absorb best practices from wherever they have been developed, and inevitably, the U.S. experience has served as a major source of ideas. But while Western management principles are well known, Indian executives report they are not necessarily emulated. Rather, over the past two decades, Indian business executives have evolved their own leadership style and developed ideas that reflect a unique cultural heritage and history.

Number of students completing Wharton School MBA program, 1990–2008

Source: Graduate Program, Wharton School, 2008.

Number of Graduate Management Admission Tests (GMAT) taken in India and China, 2000–2008

Sources: Graduate Management Admission Council, Asian Geographic Trend Report for Examinees Taking the Graduate Management Admission Test, 2002-2006 (McLean, VA: Graduate Management Admission Council, 2007); Graduate Management Admission Council, Asian Geographic Trend Report for GMAT Examinees, 2003-07 (McLean, VA: Graduate Management Admission Council, 2008); and Graduate Management Admission Council, Asian Geographic Trend Report for GMAT Examinees, 2004–08 (McLean, VA: Graduate Management Admission Council, 2009).

When Dale Berra, son of baseball icon (and legendary malapropist) Yogi Berra, was asked whether he was similar to his father, he replied no, their similarities were different. So it is with Indian business leaders. As similar as they are in many ways to American business leaders, their “similarities” are also different. Both sets of leaders, Indian and American, preside over demanding worlds, both bring a vision of where they want to take their enterprise, both are called on to make timely decisions, and both use much the same skill set. But at the same time, American and Indian executives have evolved distinct approaches to their positions—critical leadership distinctions that, in India’s case, have helped the nation’s businesses thrive. As ICICI’s K. V. Kamath summed up, “Time and again it has been proved that the Western model of doing business would not be a success here.”8

We identified the broad outlines of those “similar differences” in the opening chapter, and in this chapter we offer more specific assessment of the second of our four principal practices of the India Way. Emphasizing improvisation and adaptability, Indian business leaders stress sideways movements into areas with promising prospects and the building of a model of what should work by witnessing what does work. Utilizing a trial-and-error method, they draw upon the virtues of flexibility and resilience in the face of obstacles and challenges. We have found that this is also closely coupled with aspects of the fourth principle theme. Emphasizing broad mission and purpose, Indian business leaders also place special emphasis on personal values, a vision of growth, and strategic thinking.

Improvisation and Adaptability

Indian business leaders, we found, had no great desire to reinvent the wheel when it came to strategic thinking. For the most part, they would have been content to follow well-established Western practices, but the on-the-ground realities of establishing and nurturing companies in a dynamically changing and unique business climate left them little choice but to write their own how-to manuals. Rather than being imposed from above, their course involved making numerous operational bets, watching what worked, and then codifying the tangible successes into a more systematic framework : the trial-and-error path from good to great. In traveling this frequently tortuous and oft-changing path, they found that flexibility and resilience proved essential.

Trial and Error

Deepak Parekh, executive chairman of Housing Development Finance Corporation (HDFC), emphasized customer focus with a see-what-works approach. “Being the pioneers in housing finance in India for the middle class, we had no model to emulate,” he said. “So we adopted the ‘learning by doing’ philosophy.” Earlier in the decade, “most Indians were rather debt averse, but what we realized is that our customers didn’t need just money, they needed counseling—legal and technical advice on the property they were purchasing—and we provided it in-house. Each decision, whether on product development, pricing, or office automation and office layout, was oriented towards enhancing customer satisfaction. Understanding the customer’s needs was our key focus, and that’s where I think we made the difference.” Parekh characterized the process as iterative. His company’s direction must be “strengthened and nurtured by an analytical ability that assesses emerging environments and strategic alternatives and exploits opportunities as they emerge.”

Analjit Singh, cofounder and chairman of Max India, a company involved in information, health-care, and financial services, emphasized the necessity for flexible thinking as timelines shorten and tempos increase. “The time to make mistakes and learn over longer durations has been compressed,” he said. “If you put a strategy in place, you’ve got to be open minded enough as a management team to go back to the drawing board as often as you need to tweak it.” Planning, of necessity, is a work in progress, a product of what he termed strategy-based learning.

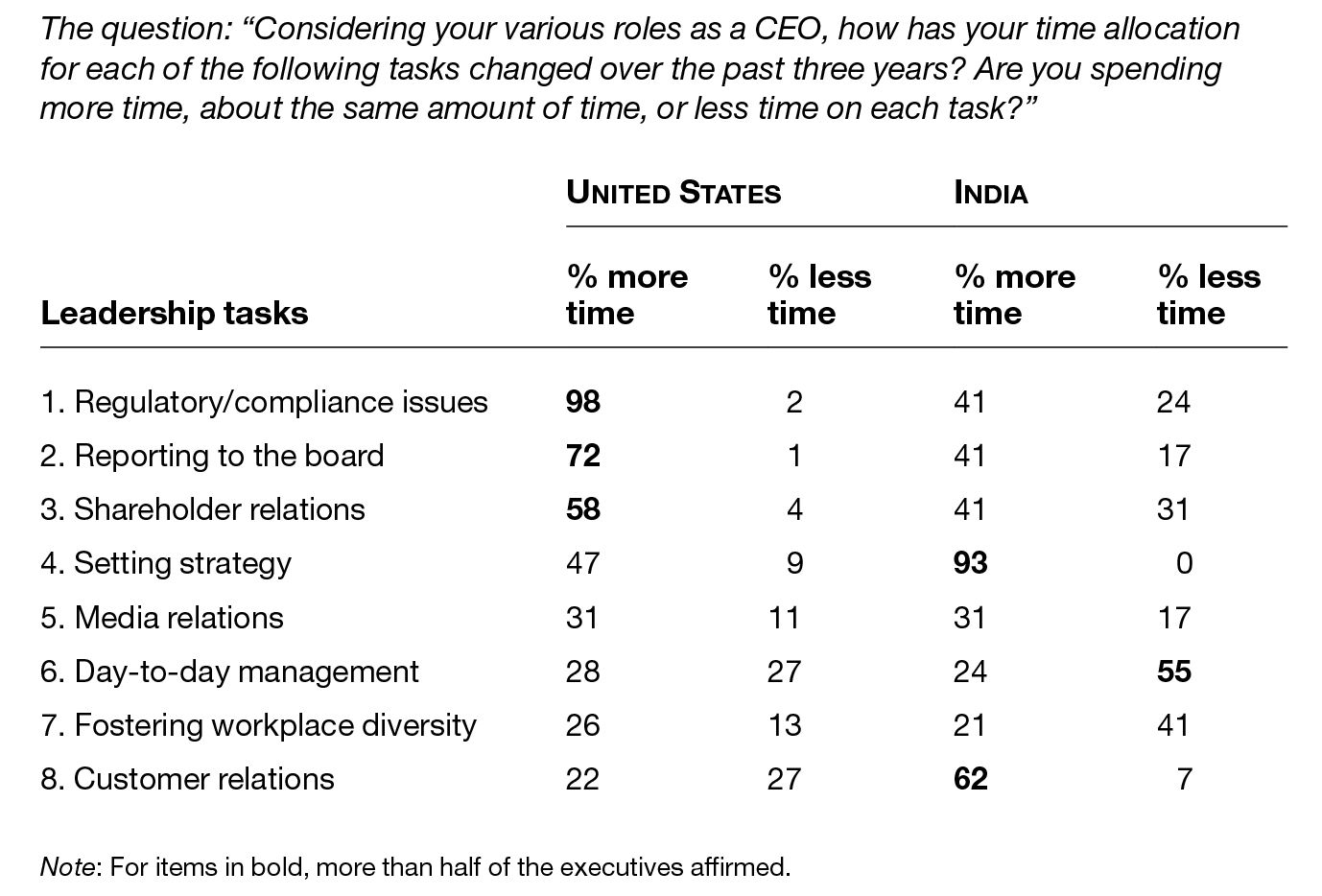

Is strategic thinking any less important to Indian business leaders than elsewhere? Hardly. If anything, it has become relatively more important in recent years, especially as compared with the United States. As table 4-1 shows, business leaders in both countries said they were devoting more time to just about everything.9 However, American business leaders reported the largest time-demand increases in areas of governance issues, including regulatory, board, and shareholder relations. Meanwhile, customer relationships were the only area seeing a net decline for American executives, while such relationships represented the second-greatest increase in demand for Indian executives, just behind “setting strategy.”

How Indian and U.S. business leaders have changed their allocation of time over the past three years

An even more telling discrepancy emerged in a 2007 Conference Board survey of chief executives worldwide. When asked to identify their most critical challenges from among several dozen, American executives ranked “consistent execution of strategy” considerably above “speed, flexibility, [and] adaptability to change.” Their Indian counterparts reversed the ranking.10

In setting direction, Indian executives have understandably developed a more inductive and customer-tested approach. Given the unknowns about what customers really want to purchase and given the convulsive growth in many Indian markets—the country had fewer than 11 million mobile-phone subscribers at the end of 2002 and some 347 million by the end of 2008—executives viewed their decision-making process as a matter of recurrently testing the waters.11 Through trial, error, and trial again, they built their product and service lines from the bottom up, focused on emerging customer demands and ever sensitive to the crosswinds moving customer preferences in one direction or another.

Flexibility and Resilience

When asked how they most differed from Western business leaders, a number of Indian executives reported being more adaptable, more flexible, and more resilient—characteristics partially explained by the prereform Indian business environment. Even today, after significant economic liberalization, India’s industrial infrastructure remains abysmal. When McKinsey asked senior managers at multinational companies to rate the infrastructure of sixteen countries, they placed India in a tie for last .12 In 2004, India devoted $2 billion to improving its roads, while China invested $30 billion.13

Yet the bureaucratic and structural problems that had been so vexing in the executives’ early careers also instilled a personal steeliness. “Professional Indian leaders,” Hindustan Unilever’s Manvinder Singh Banga observed, are “quite distinct from what I see anywhere else, and they are distinct primarily because they have been trained or groomed in an extremely fluid, dynamic, and uncertain environment. The business environment in India has all those dimensions of poor infrastructure, uncertain infrastructure, and challenges from the regulatory side and with labor relations. These multiple challenges are much more than the typical consumer- or trade-challenge that you face anywhere else in the world.”

As a result, Banga concluded, “Indian management is a much better-rounded management than people who have trained and evolved in more stable market places in the world.” For one, Indian business leaders “have a much greater ability to cope with uncertainty, they don’t get disturbed by uncertain events, they keep an even keel, and they are more balanced as they pick their pathway through.” Second, “they also tend to be more creative as a result because they have to face these sorts of untoward situations almost on a daily basis, and therefore they have to really stretch into creativity across the whole business model. They are creatively thinking about the whole business model and all the levers of business.”

In building an organization, Deepak Parekh of HDFC said executives must be energetic trailblazers. “Success in India is a struggle of the hurdle economy, where 5x energy is required to produce x,” he said. “This is quite the reverse in most modern societies. The true leader is one who can counter this framework and, like an icebreaker, cut through pack ice and create a channel for others to follow. Not only will he need a machine to undertake that task, but also the inspiration, patience, and optimism to drive it and the energy to sustain it over long periods of time.”

Vivek Nair, vice-chairman and managing director of Hotel Leela Venture Ltd., was reminded of the importance of personal resilience both during the aftermath of 9/11 and its devastating impact on the travel and hotel industry, and during the major rebound that followed several years later. The months after 9/11 proved extremely stressful for the hospitality industry, even in India, with suddenly empty hotel rooms necessitating drastic wage reductions and cost cutting. Not long after, though, business travel to India rebounded, with annual increases of 6 to 7 percent, and foreign tourism shot up by some 25 percent. In anticipation of the rebound, the company had invested $600 million in a set of new hotels, including one in Bangalore that has proved to be among the best-performing hotels in India. A vital capacity in weathering the storm, in Nair’s view, was his ability to flexibly respond to such huge swings in demand. During the downswing, it had been essential, he said, to “inspire confidence” among the hotel’s employees that “it was not the end of the world.” They could not understand, he found, “how things could change so radically in a matter of just one moment.” But he worked hard to reassure them, meeting with many individually and in groups. In time, the employees became more ready than would otherwise have been the case to get back on the hotel’s “high-growth path”—the path he sought and the one that the company returned to several years later.

Jugaad and Adaptation

An appreciation for the turbulent and often frustrating barriers to doing business is essential—but so too is active surmounting of them. Creative adaptation, not weary resignation, is the way.

Vijay Mahajan, chief executive of BASIX Group, a microfinance organization, argued for many in offering his appraisal of the power of jugaad, an ability “to manage somehow, in spite of lack of resources.” It constitutes a cornerstone of Indian enterprise, in his view, and the “spirit of jugaad has enabled the Indian businessman to survive and get by in an economy which was until the late 1990s oppressed by controls and stymied by a lack of widespread purchasing power. Adjust, of course, is the English word, but spoken in various local accents. It is used in a wide range of situations, usually with a plaintive smile. One can use it in a crowded bus, where three people are already seated on a seat for two, requesting them to ‘adjust,’ to accommodate a fourth person! Or it is used by businessmen when they meet government officials, seeking to ‘adjust’ various regulations, obviously for a consideration, to speed up the myriad permissions still required to do anything in India.” Mahajan’s ideas in many ways reflected the entrepreneurship that existed across business enterprises of all sizes—the ability to navigate a complex environment, find innovative ways to do business, and adapt to unfavorable business conditions.

Subhash Chandra of Zee Entertainment Enterprises said that in his experience Indian leaders seemed more adaptable than U.S. business executives. “We can bring our level of thinking down and meet with a truck driver and deal with him at his level,” he said, “and at the same time we can also bring ourselves up to the level of the head of the state if required and then deal with him at that level.

“I remember when I was starting my business career, I used to run an edible oil extraction plant in my hometown. I wanted to learn how to drive a truck, and so I befriended my company truck driver, and he taught me to drive the truck, and at the same time I used to run that business even as the CEO. Later, I could go to the chief minister of the state and request him to give me an electricity connection because that was the challenge in those days due to power shortage.” Now, he went on, this early experience with direct engagement had become an important asset for leading his business through market, rather than licensing, challenges.

Broad Mission and Purpose

Many Indian executives placed special stress on articulating a forward-looking vision while instilling shared values to anchor their companies. Many further emphasized the importance of aligning their vision with long-term company values, while still energizing and exciting the company’s current employees. Here the difference with American executives appeared to us to be more a matter of content than kind. Both offer long-term pictures of the path ahead, but rarely did the frequent U.S. mantra of double-digit growth in earnings per share appear in our interviews. For Indian business leaders, the long-term pictures were more a matter of reaching millions of customers with new kinds of products, or helping to lift vast numbers from poverty, or giving people of limited means what had only been available to the affluent, whether air travel, mobile communication, or auto transport. While such agendas may create equivocal or even adverse reaction among Western investors, Indian business leaders used them to help create unequivocal and affirmative allegiance among company employees.

Vision and Values

Subodh Bhargava, chairman of Videsh Sanchar Nigam Ltd. (VSNL, renamed Tata Communications in 2007), told us that the maintenance of “shared values and shared vision” was critical to his own leadership. The company has made many course corrections, even strategic changes, over the past twenty-five years, he said, but the values and vision always served as the “first anchor.” Bhargava emphasized the importance of his line managers “walking the talk”—living by those values and vision. Among the specific values held constant by him over the past quarter century have been personal integrity and ensuring that company decisions are apolitical, fair, and “secular.” He stressed “extensive communication and absolute transparency” within the company as a way of ensuring that those values are widely embraced by his managers.

Similarly, Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw, executive chairman and managing director of Biocon Ltd., emphasized the importance of communicating clearly and truthfully to help shape organizational values: “If you are honest and up-front,” she said, “people trust you and never lose that trust. I think people need to trust you to be inspired by you.” B. Muthuraman, managing director of Tata Steel Ltd., emphasized “being a visionary” as a vital leadership quality. “By being visionary,” he explained, “I mean somebody who is able to make people envision their future” and then “energize, enthuse, and empower them” to strive toward that goal.

Company Vision

Deepak Parekh, Executive Chairman

Housing Development Finance Corporation

Over the years, I have repeatedly been asked, “What has been HDFC’s guiding principle to being the vanguard of housing finance in India?” My reply is simple: you must get in first.

Straightforward as it may appear, it requires tremendous vision to do so. One must be able to visualize the future, anticipate emerging patterns, and spot business opportunities in them. One must have the ability to create mental maps of possibilities and the relevant conditions that enable things to happen.

If I had to put it in a single sentence, I would say that a leader must have the exceptional capability of visualizing and inventing the future—an uncanny intuitiveness for what lies ahead. Jonathan Swift, author of Gulliver’s Travels, put it so succinctly when he said that vision is the art of seeing the invisible . . .

All great organizations have a unique characteristic among their leadership teams. Not only do they have a clear vision of where they want to be in the future; they effectively convey this vision to their employees and get them to believe in it. A leader must have the ability to see in a way that compels others to sit up and take notice. People want a strong vision of where they are headed. And they want to be part of it.

For a leader’s vision to become a reality, his people must believe in it. To get your people sold on your vision, you must possess passion for it. Be hands-on. Get involved. Though I do not own HDFC, I have run it as if I do. All decisions of investment, lending, and dividend that I take make me feel as if I own 100 percent of my company. I do what I would have done if the company was owned by me. I have acted as an entrepreneur even though I am just a salaried employee.

Creating afresh requires leadership of an extraordinary dimension. Not only must the leader have the foresight to see the big picture before anyone else does but must also possess the ability to systematically break it down and zero in on its components.

A vision must never lie dormant. It must be consistently strengthened and nurtured by an analytical ability that assesses emerging environments and strategic alternatives and exploits opportunities as they emerge . . .

Never underestimate the importance of vision. You cannot be an effective leader if you don’t have a vision—either for yourself or for the organization. It is what one sees or feels before any systematic reasoning can be structured. A vision is like a map that guides one through a tangle of bewildering complexities.

Automaker Mahindra’s vice-chairman and managing director, Anand Mahindra, echoed that sentiment when he told us that, as a “business head in India, if you didn’t have some perspective or some road map or some vision of where you thought the company [was] going, and therefore what opportunities lay ahead, you would not have been able to position yourselves [during] the last fifteen years to take advantage of those opportunities. Where I have added the most value and where I have gone and made the most difference [is] in the ability to just have an idea in my mind as to what the future should look like in terms of everything: how the organization should look, which areas it should go down,” and what should be the appropriate “business model.” For Housing Development Finance Corporation’s Deepak Parekh, it is a matter of visualizing the future to anticipate the business opportunities ahead (see “Company Vision”).

Expansive Thinking

As both a corollary of shared values and vision and a technique to realize these overarching goals, expansive thinking was placed by many of the executives at the top of their personal list. Farsighted judgment springs from many sources: experience, intuitive judgment, as well as detailed analysis of the most promising opportunities ahead. Azim Premji, executive chairman of Wipro Ltd., described broad thinking as combining “intuitive judgment and professional evaluation” with an “ability to see around corners.”

For Manvinder Singh Banga, former chairman and CEO of Hindustan Unilever, India’s largest consumer products company, expansive thinking is a matter of synthesizing many contextual threads: “The most important role for a leader today,” he said, is being able “to make sense of all the different trends that are there in the market, so whether it is consumer trends, political trends, economic trends, technology trends—add them up and try to work out a searchlight that illuminates the path to sustainable profitable growth.” Such thinking then must be conveyed throughout the organization “to get everybody on the same page so that they understand the searchlight, the pathway, and see it as clearly as you do.”

Drawing on one of Star Trek’s catchphrases—“Dare to go where no man has gone before”—Rajesh Hukku of i-Flex Solutions, a provider of information technology services to the banking industry, defined farsighted judgment as “not just to think differently to show some difference, but think differently in terms of how you can change the lives of your customers.” Broad thinking, for him, required a search for innovation and “doing things that have not been tried before.”

Virtually all the leaders we interviewed stressed the importance of their own proactive roles in thinking broadly and evolving that thinking as experience dictated. Zee Entertainment chairman Subhash Chandra, for instance, emphasized the importance of transcending the immediate situation and then letting that larger picture guide his actions. When “considering some particular subject at the very, very micro level,” he said, he must at the same time “create a picture of the macro situation.” Conversely, he said, he must also be able to translate the macro situation back to the micro level. Chandra confessed to a tendency to get into the details of execution himself, but he also forced himself to stand back when he realized that he could “lose sight of the many issues that must be simultaneously considered” by a person in his leadership position.

Communicating Vision and Values

As important as it is to have a guiding vision and values, broadly communicating vision and values was seen as even more critical. On one hand, this would seem an obvious point: a leader’s values and vision must be known and appreciated throughout the company to be fully realized. Yet time and again in our research and observations, we have been surprised by how little the chief executive’s values and vision were appreciated or even understood by frontline employees.

Nowhere was this effort to communicate executive values and vision more important—and more challenging—than among companies that had previously enjoyed government-protected markets. Consider the uphill struggle R. S. P. Sinha, executive chairman and managing director of the government-owned Mahanagar Telephone Nigam Ltd. (MTNL), faced in 2000 when the New Delhi and Mumbai areas were thrown open to competition. His first order of business, Sinha said, was to craft a vision that could provide for sustainable advantage in a fast-moving market and then to instill it among sixty thousand employees who were accustomed to having the turf to themselves. To change this work culture and ensure the “clarity of our thinking and action and vision,” Sinha spent much of his time speaking face-to-face with throngs of employees.

Or consider the unique challenges faced by Subir Raha, former chairman and managing director of Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC), when he joined the company in 2001. Publicly traded but still majority owned by the Indian government, ONGC was responsible for more than three-quarters of the country’s oil and gas production. Though demand was up, ONGC was not. “The company was stagnating in every aspect of performance, operational [and] financial,” Raha observed. The firm’s results were negative, employees were demoralized, and its public image was poor.

Building Bank of Baroda

Once among the country’s most respected financial institutions, Bank of Baroda was increasingly seen as a socialist relic in postreform India. The national government controlled 51 percent of its shares. Bank of Baroda paid well below what private competitors did. The bank’s long-serving employees were highly resistant to change, but management couldn’t use wages or stock options as motivators. The ability to fire and lay off employees was even more constrained. As the 1990s moved into the 2000s, the bank found itself eclipsed by faster, more nimble private-sector competitors.

Enter Anil K. Khandelwal, who took over as chief executive in 2005.

Khandelwal began the bank’s transformation with his own version of a burning platform: meeting with bank managers and showing them financial-analyst reports recommending that investors not buy Bank of Baroda stock. Of course, the managers didn’t have stock options, so this was an appeal to mission—this is a bank that should be working for the betterment of India—and also to personal pride: it’s embarrassing to work in an organization of which experts think so little.

The next thing Khandelwal did was to revamp the bank’s branding with a new trademark and a new spokesperson. He then ran out a pilot program in which some branches would be open twelve hours a day, from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m.—an innovation that would be radical even at most U.S. banks.

Khandelwal had a vision of how to improve Bank of Baroda’s market position, but implementation relied on direct communication with staff. He called all the employees of these pilot branches to headquarters for a meeting—“from manager to messenger,” as he put it—and made a sales pitch about the need to change, at the same time asking for the employees’ help to do it. Because he had empowered his workers, rather than forcing change on them, they agreed to staff their branches from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. without any overtime pay or extra compensation. The next part of the transformation, and the most important, was to have these local branches design their own marketing events to announce the new schedule, leading to an explosion of creativity—parades, pageants, you name it.

The twelve-hour banking trial was eventually rolled out nationwide, but with each local branch taking responsibility for execution. Since then, the bank has introduced “twenty-fourhour human banking” in several locations, in which regular employees, not a faraway call center, staff the branch around the clock. Since branch employees took the lead in these rollouts as well, communication was critical. Khandelwal wrote employees letters every week, explaining the goals and the progress so far, and often met with the local branches to make the case for change.

Once the bank started to get public attention for these innovations, employee pride rose in the bank’s mission. This morale boost allowed Khandelwal to convince workers to accept as necessary massive investments in new technology that would cut and restructure jobs. Along the way, he also introduced such employee-relations innovations as a direct help line to his office for those facing crucial problems in their part of the organization and a talent-hunt program to find and develop high-performing employees within Bank of Baroda. He personally directs these programs, saying that human resource issues “cannot be delegated.”

Without using carrots or sticks, Khandelwal turned a stodgy, government bank into one competitive with leading private banks. He accomplished this by creating a sense of mission, communicating his vision, and persuading employees by empowering and engaging them. His job before becoming chief executive (to return to a theme of the previous chapter): head of human resources.

To remedy the situation, Raha set forward a new long-term vision for the company, with a set of accompanying benchmarks for as far out as 2020. “This created a perception,” he recalled, “among employees and external stakeholders that we intended to be around in the long haul and that we were not going to close out the company in three years or five years.” By going public with the goals on a twenty-year time frame, he said, “people had their confidence restored !” (See also “Building Bank of Baroda.”)

Transformational Leadership

The melding together of the Indian business executives’ exceptional stress on improvisation, adaptability, mission, and purpose had yielded a leadership style that resembles what is sometimes captured in the concept of transformational leadership—an approach different in tenor from what is often referenced as transactional leadership.14

Transactional leadership is described as striking deals with subordinates, almost like a transaction, where the leader matches the individual’s interests and needs to specific job-related outcomes: you want a promotion, meet these sales targets. Transformational leadership—or as it is sometimes popularly known, charismatic leadership—is a very different process through which the leader influences the interests and needs of subordinates, inspiring them to care about the goals of the organization: you should identify with the success of the company because its mission is important, and you should work hard because you care about that mission.

Leadership style is in part defined by the behavior of bosses toward their subordinates and the efforts made to motivate and influence those who report to the top, and we anticipated the possibility of a third style of leadership—what some might even call nonleadership: a more passive approach in which executives essentially leave subordinates alone and let the administrative systems manage their behavior. The most formal of the passive approaches is management by exception, where leaders intervene only to correct problems. Passive leadership makes sense with highly empowered employees, but it is not the only way to lead empowered subordinates.

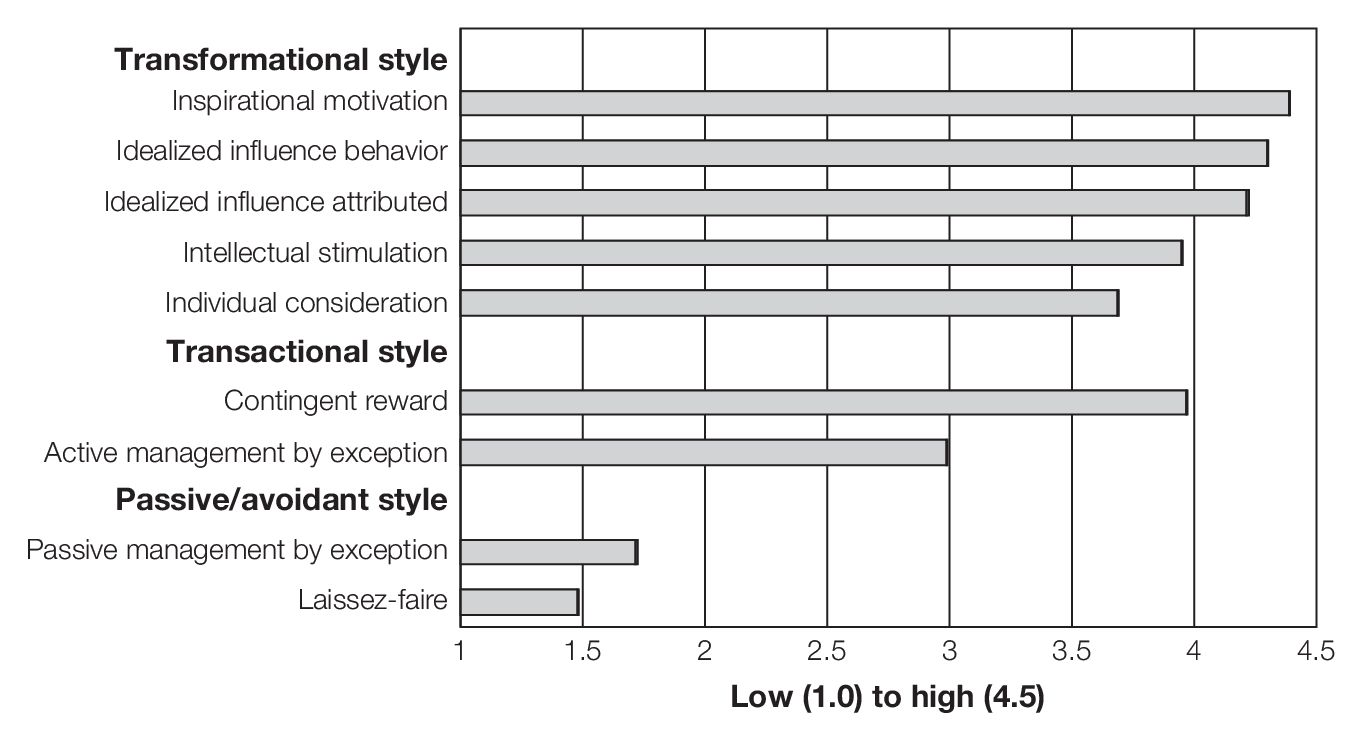

To examine the style of Indian executives, we used the most widely used assessment of leadership in the United States, the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ).15 We asked the directors of human resources at the companies whose executives we interviewed to assess the leadership style of their top bosses. (As part of the MLQ process, individual questions ask about specific leadership behavior and the responses are then gathered into more general practices.) Not surprisingly, given the picture of Indian business leadership already developed—actively engaged in building mission-driven organizations—the executives scored low on passive and avoidance practices, as seen in figure 4-3. Nor were we surprised to see that Indian business leaders ranked highest in practices that fall generally under “transformational style”: inspirational motivation, idealized influence, intellectual stimulation, and individual consideration. On the transactional side, Indian leaders, like their American counterparts, are quick to use contingent reward—that is, rewards based on performance—but less prone to manage by exception: look for mistakes.

When we compared these results with those from a sample of forty-eight chief executives of U.S. Fortune 500 companies, however, we found that the American leaders were significantly more likely to use transactional leadership styles than were our Indian executives. Another study of fifty-six American chief executives also suggested that Indian executives create a significantly greater sense of empowerment among employees, scoring higher, for instance, on the “intellectual stimulation” category. 16

Improvisation and adaptability, mission and purpose—together the foundation of a more transformational style—were repeatedly stressed in our interviews with the Indian business leaders. They were evident as well in the leaders’ narratives of how they had built their companies in the post-1991 era of liberalization. For illustration, we turn to India’s largest nonstate-owned financial institution, ICICI Bank, and the role of its long-serving transformational chief executive, Kundapur Vaman Kamath.

Leadership styles of Indian business leaders

Sources: Survey of Indian Companies; and H. L. Tosi et al., “CEO Charisma, Compensation, and Firm Performance,” Leadership Quarterly 15, no. 3 (2004): 405–420.

Leading ICICI Bank

In 1971, when K. V. Kamath began his career at the original Industrial Credit and Investment Corporation of India, the bank—created by the World Bank and the Indian government—had a relatively modest mandate: project financing for the private sector. Kamath stayed on for seventeen years before decamping for a stint with the Asian Development Bank. In 1996 he returned to a radically different ICICI as chief executive, overseeing the bank’s massive transformations in postreform India. Kamath’s ICICI career, in short, spans the “great divide” of the Indian economy, just as his bank is a powerful expression of the modern-day Indian business juggernaut. More to the point for our immediate purposes, the leadership principles that have evolved over Kamath’s long career neatly encapsulate the themes of this chapter.

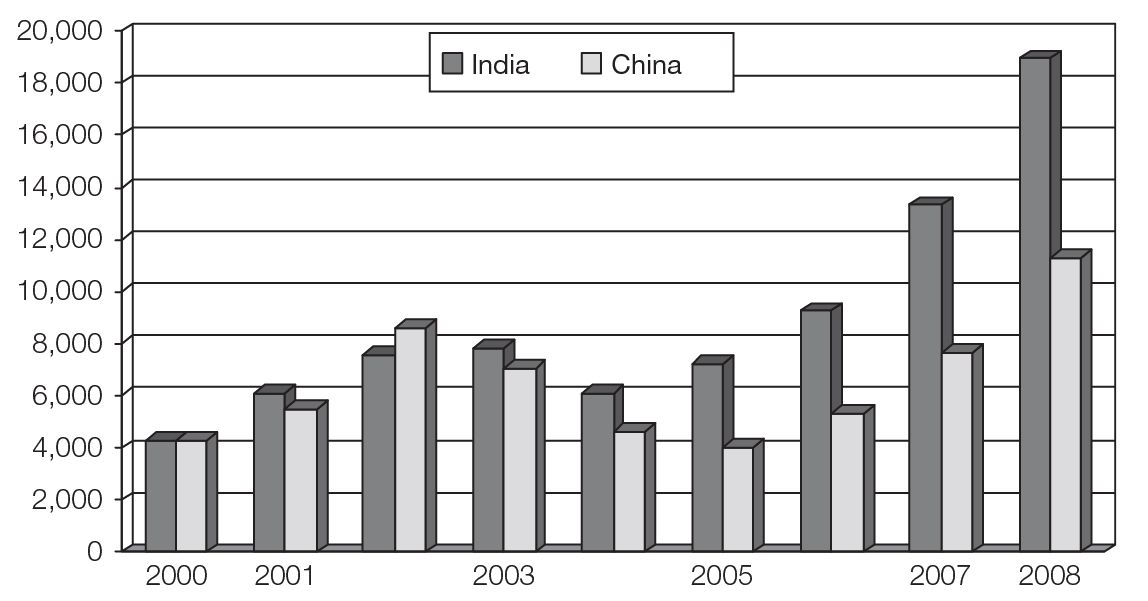

In 2000, four years into his new job, Kamath listed ICICI on the New York Stock Exchange, and it soon emerged as India’s largest privately owned bank. ICICI’s annual revenue of $625 million (27.2 billion rupees) in fiscal year 2002 rose to $9.1 billion (396 billion rupees) in 2008, and the company grew from 7,700 to 40,686 employees over the same period (see figure 4-4). In just seven years, the bank’s employees quintupled and revenue rose more than thirteenfold. With managed assets of more than $100 billion by 2008, it became the country’s largest private-sector commercial bank, investment bank, and insurance provider. ICICI ran India’s biggest online trading operation and managed India’s largest private equity and venture capital funds. It handled a quarter of all private remittances flowing into India, an especially significant figure since India is the world’s largest recipient of remittances.17

In guiding this explosive growth, Kamath worked closely with the long-serving nonexecutive board chairman and former CEO Narayanan Vaghul. Together, they created a vision of transforming the institution from a development bank into a corporate and retail bank, and then into a universal bank that could provide a full array of financial services, ranging from mobile and private banking to life insurance and venture funds. Yet the implementation of these goals—and the rapid expansion that followed—was largely accomplished without bringing in experienced banking veterans who could help ICICI adjust to new business opportunities. Instead, the bank’s leadership opted to combine expansive thinking about the new markets with a trial-and-error approach to finding what worked in largely untested markets.

Direct Involvement: Chanda Kochhar

One of ICICI’s primary movers into the new markets had been Chanda Kochhar. Without a road map to follow, Kochhar relied heavily on direct hands-on engagement to learn how to build businesses in four distinct areas of banking. She first joined ICICI’s corporate banking, then set up the bank’s financing for infrastructure projects, followed by retail banking, before moving on to the firm’s international banking operations. “On a personal level, it wasn’t always easy,” Kochhar recalled. “But as a leader, I think you need to be adaptable, so you can quickly understand and move forward in new business situations.”

When Kochhar joined corporate banking, she realized that each banking division dealt separately—and relatively passively—with its corporate clients. Inventing her way forward, Kochhar created a nine-person team that was drawn from investment banking, commercial banking, securities trading, and other product areas. Her goal was to learn the principles of integrated product selling and what she termed multifaceted leadership. That required rapidly absorbing from others what she initially knew so little about. “I learned it is possible to quickly share knowledge and ideas with each other, rather than sitting on a pedestal, saying, ‘I’m the boss, and I’m not here to learn from anybody.’”

Kochhar convened her top team every morning and evening to transform how she and her senior bankers conducted business with major clients. Rather than waiting for customers to make a specific request and then responding with a product offering, the bank identified which clients most likely needed what products, and then preemptively proposed an appropriate set of products. “Instead of sitting at our desks and waiting for clients to come and ask for products,” Kochhar said, “we had to get out there and market the products to our clients.”

After this success, Kochhar took a leap of faith when she joined ICICI’s retail banking sector. At the time, she was running the corporate business division that was responsible for almost half of the bank’s profits and assets; consumer credit was then less than 1 percent of the firm’s revenue. Not surprisingly, when CEO Kamath asked her to take it over, Kochhar initially balked. “Why should I move from handling 50 percent of the bank to handling 1 percent of the bank?” she asked. In his characteristic way of foreseeing a robust opportunity even without a sure way to exploit it, Kamath responded, “Because I want you to make this business more than 50 percent of the bank.”

Into the Unknown

ICICI’s Kochhar-led entry into retail banking was itself uncharted territory. The “consumer-credit market was very, very new for India and for ICICI,” she recalled. “I was trying to create something that was not just new for me but absolutely unknown to the organization and the country as a whole.”

Fortunately, it turned out that retail banking required a skill that Kochhar had developed: a personal process of learning to lead by doing. When ICICI finally entered the retail banking industry in 2000—offering automobile, two-wheeler, and commercial vehicle loans, along with home financing and credit cards—the market was still modest, but the bank was betting it would soon explode. “Let’s plan not for the small size the industry is today,” Kochhar thought, but “for what the industry is going to be five years from now.” Kochhar estimated that as India’s annual per capita income rose above $500, substantial numbers of consumers would begin to spend and borrow, and retail banking did indeed expand as anticipated, growing by more than 50 percent per year during the mid-2000s.

To take advantage of this future market, Kochhar developed her leadership cadre from the outside. “I had to create a team of people who had worked in this industry for other banks. What I brought to that team was ICICI’s strategic thinking, but when it came to domain knowledge or product nuances, I had to learn from the team. In that way, I was a kind of a leadership bridge between ICICI’s way of thinking on the one hand and the domain knowledge of the team on the other hand. I had to arrive at decisions not based on past experience, but on a mix of their domain knowledge and my gut feel.”

When Kochhar began her mission, the entire country had fewer than three hundred ATMs, but on the premise that success in retail banking depended on scale economies, ICICI opted to set up three thousand ATMs over the next two years (and now supports some four thousand, one of the largest networks in Indian banking). “This was a big decision,” recalled Kochhar, “for which we had no past experience to tell us whether it was correct or not.” It did prove correct, and within four years of entering the fray, the bank had moved from no share of a relatively small retail market to half of a substantial retail sector, making it the country’s largest player in the burgeoning consumer-credit business.

Chanda Kochhar successively learned to lead within each of the bank’s new areas of fast expansion. She did so through direct involvement, premised on a vision of rapidly ramping up a host of new products to transform ICICI from an industrial agency into a universal bank. Her approach entailed a combination of farsighted judgment about how that vision should translate within all of the markets, with an experimental approach to discovering what succeeded in each of them. “We need to start work with the idea that we’re going to learn every day. I learn, even at my position, every single day. Whenever there’s a challenge, I see an opportunity in it: you have to find a way of converting challenges into opportunities. That’s the way one learns and moves forward.”

A Team of Leaders

K. V. Kamath attributed his bank’s trial-and-error expansion to the ready-to-learn quality among his top executives and their teams of managers. “If you look at what we have done in twelve years, and more so in the last five years, the cornerstone of whatever success we have had is people.” The people whom he had in place or put in place during the late 1990s after his return from East Asia were the “talent that built the bank.” Even though at the time they did “not possess any of the core skills required to build or run a commercial bank,” they brought broad qualities to their jobs: intellect, entrepreneurship, resilience, adaptability, and a capacity to master what they must.

Placing significant resources in the hands of little-tested people meant, in essence, working without a safety net, but Kamath felt that he had no alternative since the country had virtually no bankers experienced in the areas he was seeking to build. “In hindsight,” he admitted, “it is now clear to me that we took a huge risk.”

The risks were doubled, at least, by the low-operating-cost model that rural banking in India required. Whereas a typical deposit in the West might be $10,000, a typical deposit in urban India was apt to be no more than $1,000—and in rural India only a tenth of that. That meant operating expenses had to be pared down proportionately: urban banking in India had to be conducted at one-tenth the cost of banking in the West, and rural banking at one-hundredth. “We need to be able to conceptualize how to deliver value to this market at an extremely low cost,” Kamath said. “That’s where the challenge is, as well as the opportunity and the excitement.”

Here, too, Kamath and his top team knew that they would have to invent their way forward if they were to successfully bank millions of unbanked villagers. A scaled-down urban branch model was still prohibitively expensive, so Kamath and his team turned to alternative, far less costly avenues for reaching the poor, ranging from nonprofit microfinance groups to local fertilizer distributors. Kamath was confident that his team could learn to profitably reach millions of poor customers through partnerships with a host of very low-cost, on-the-ground networks that already cut across rural India. “If we can do this—and we are fairly sure that we can—I think the rewards could be enormous.”

In selecting people such as Chanda Kochhar for leadership roles in such a risky environment, Kamath had drawn on five criteria:

First, I look for intellect or a high level of competence. Second, I seek out entrepreneurial leaders who have the ability to pick the right people. That means looking at how the person has performed in other contexts to build teams. People who have the ability to build and manage teams are very valuable. Third, the person must have a can-do attitude. What sort of reaction do you get when you talk to him or her about a challenge? Will he go for it or is it a problem? Fourth, the right people have the ability to withstand shocks without getting flustered or losing direction. Finally, whether this is an entrepreneurial quality or not, it is an important quality that I look for in people whom we pick as leaders: the ability to focus, focus, focus without getting diverted from the core business, and to correct your course when things start going offtrack. In executing any strategy, whether you are setting up a new business unit or trying to reach profit or budget targets, things never happen quite the way your models may have predicted. That is why you need the ability to correct your course as you go along.

For all this to cohere, the company’s vision and values proved the essential glue. “I think for me really the key is keeping the organizational culture right,” said Kamath. When asked what he would view as his most important advice to a successor, he said, “Make sure that the DNA of the organization is what it is, or if you think that it needs to be corrected, articulate it very clearly to make sure that it happens.” A central feature of the bank’s cultural DNA was the defining concept of entrepreneurship. “The key challenge is to look to new horizons,” offered Kamath. “Our growth so far has been based on our ability to identify opportunity horizons very early and build businesses to scale those horizons.”

Witness, for example, the determination of K. V. Kamath to have his bank, ICICI, India’s largest privately owned financial institution, join the ranks of international behemoths like Citigroup, Deutsche Bank, and Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ. “If there ever be an Ivy League of global banks,” Kamath said in early 2008, “in five to ten years we have to have a few banks from China and a few from India in that league.” His bank, he assured us, would count among them.18

A New Chief Executive

The unique Indian approach to achieving that growth was also evident in the way Kamath, who stepped down as ICICI chief executive in May 2009, went about choosing his own successor. Among the rumored possibilities was Aditya Puri, the widely respected managing director of archcompetitor HDFC Bank—a choice that would have been well in keeping with the U.S. model, where top talent tends to hopscotch among rivals (JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon had previously worked at Citibank; the last CEO of Merrill Lynch had come up through Goldman Sachs). But as is common among India’s leading enterprises, K. V. Kamath had been growing his own bench.

Kamath assigned a half-dozen high-potential managers to a series of varied and increasingly responsible jobs, and then he studied them as they prospered, and in some cases stumbled. He collected 360-degree feedback on their leadership qualities from twenty to twenty-five of each of their peers and subordinates and invited the best to take an active part in the bank’s board meetings and to accompany him to the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. In the end, he and the board opted for a seasoned insider, chief financial officer Chanda Kochhar.19

Invented in India

In thinking about the differences between Indian business leadership and that in other major economies, we oddly found ourselves reflecting on cars: how American companies mass-produced automobiles while Toyota used lean manufacturing techniques. These distinct production models meant that businesses like General Motors and Ford Motor Company traditionally emphasized detailed divisions of labor; short-term relations with employees, suppliers, and customers; producing large numbers of standardized products with long product cycles; maintaining large inventories of parts for assemblage; and seeking to make a good, if not perfect, automobile. Toyota, by contrast, stressed teamwork, deep long-term relations with stakeholders, making customized products with short product cycles, maintaining minimal inventories and buffers, and pressing for continuous product improvement. These differences largely emerged from the distinct production challenges auto executives faced: capital was scarce in postwar Japan, so Toyota was forced to minimize its parts inventories, leading to its now-famous operating principle of seeing all buffers as waste.20

By the same token, many of the differences between American and Indian executives were not accidental but can be traced to the distinct circumstances confronting company leaders. Among them is an Indian market environment that has been both chaotic and replete with hidden opportunities; a licensing and regulatory regime that resisted and tested the mettle of all who sought to build private enterprise (American CEOs who complain about excessive U.S. regulation could hardly comprehend what doing business was like in India prior to the 1991 reforms); and a traditional culture, rooted in Indian society, that places collective purpose above private gain.

Invented in Japan, Toyota’s flexible manufacturing methods have been adopted by automakers around the world—from Ford to Porsche—and have proved useful in improving product quality and lowering cost internationally.21 Similarly, though Indian business methods emerged as a logical product of the challenges their executives faced in an era of liberalization and growth, they are not necessarily limited to the Indian context. The India Way’s distinct combination of vision and values, trial-and-error methods, and adaptability is likely to find application by those building and leading enterprises wherever there is a market for growth that rewards expansive thinking and personal resilience. What’s more, Indian business leaders have consistently shown they share a drive to build and spread the model. Kushagra Bajaj, joint managing director of Bajaj Hindustan, the country’s largest sugar and ethanol producer, said from his own experience that compared with large American companies like Wal-Mart and General Motors, Indian companies “have that fire in the belly” and we “have the desire to go and prove ourselves to the world.”

Fully catching up with the West will require continued building on the India Way, said many of the executives, but also continued learning from all the world’s different business ways. For Mukesh Ambani, that learning dated back some three decades to his 1979 entry into the Stanford MBA program. Despite reaching the number five spot on the 2008 Forbes magazine annual roster of the world’s richest individuals, far outranking all American executives except Warren Buffett and Bill Gates, Ambani remained resolutely open to the best of what the West may still have to offer.22 “Managers from India’s private sector, multinational private sector, and the public sector are all learning from their counterparts from around the world,” he said. “They’re learning from experiences in different geographies and different sectors of the industry, and then applying them to the virgin opportunities that we have here” and abroad.

We will see whether executives elsewhere increasingly return the gaze, but we find it hard not to recommend that they do so. Of course, they should continue to draw on their own best methods—there is no reason to throw the baby out with the bathwater—but there is much to be learned from what executives in India have been inventing over the past two decades without anyone abroad quite noticing.