CHAPTER FIVE

Competitive Advantage

Delivering the Creative Value Proposition

ONCE THE PRINCIPLES of people management and executive leadership are in place and the workforce and top team are prepared and engaged, the India Way points toward building organizational architecture, company culture, and fresh approaches to reaching customers into creative value propositions. Building on people management and executive leadership, this chapter focuses on the distinctive ways in which Indian business leaders find competitive advantage and on how they succeed through creative value propositions.

We often think of strategy formation in large U.S. corporations as an analytical exercise, based on customer research, competitor intelligence, industry analysis, and perceived or documented firm-level advantage or disadvantage. The goal of a typical American company is to find the attractive opportunities and then do what is necessary to acquire or cultivate those customers, restructuring the company if necessary to develop the products or services that customers want. Doing so requires a full-time staff devoted to finding and then targeting good opportunities.

A company’s competitive strategy provides a kind of template for day-to-day business decisions but is not itself subject to short-term alteration. Carefully thought through—the raison d’être for high-end consulting firms like Bain, Booz & Co., and McKinsey—the template creates a framework for engaging in the market and guiding operational decisions. It sets forward a view on how best to compete over the next three, five, or even ten years. Indeed, competitive strategy is sometimes seen as defining the essence of what company leaders do, representing the unique value they bring to high office in return for significant compensation packages. And the unambiguous U.S. yardstick for defining successful strategy is how it translates into compelling financial results, the foundation for quarterly results and well beyond.

Being good at strategy and finance is thus a central foundation of American business leadership. Aspiring business leaders—our MBA students, for example—see strategy and finance as their ticket to the top. Over half (528 of 1,022) of the majors of the Wharton graduating MBA students in May 2008 were in strategic management or finance. After graduation, many were hoping to start at McKinsey for strategy, Goldman Sachs for finance, or their respective competitors—a career ladder that would lead to leadership roles overseeing strategy, finance, and a diverse array of other key company functions and operations, and finally to the top of the heap itself.1

Indian business leaders saw the situation quite differently, especially where strategy was concerned. They were not ready to farm out that role. Indeed, in response to our interview and survey queries, they reported that their most important personal priority was to remain the chief driver of their company’s strategy. Such a statement sounds like a recipe for disaster. Who wants the head of a large corporation meddling in the technical details of a complex process under the direction of a professional staff? It also sounds like what one would see in smaller, start-up companies. Is this a residue, then, of a time when these business leaders, many of whom were company founders, were trying to run ever-larger and more complex corporations as if they were more intimate, entrepreneurial operations?

Perhaps that plays a minor role, but another interpretation is more consistent with what we heard from the Indian executives and other observers of Indian business. They told us that the process of creating strategy is different in these firms from what we are familiar with among American companies. Strategy in these Indian firms has an emphasis on the enduring capacities, architecture, and culture of their organizations. When these executives described their business plans to us, they generally characterized their intended strategies as based on long-term, stable competencies—required in part to respond to the intensifying competition from abroad.

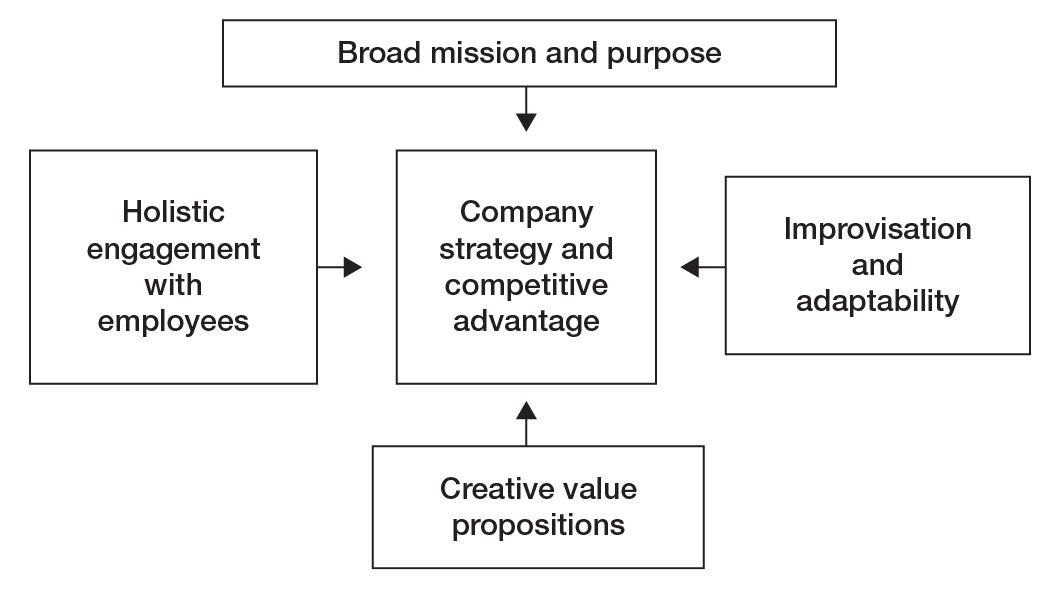

Strategy in the India Way companies comes from competencies developed within the firm and is based on the operating principles we described in chapter 1: engaging the energy and commitment of employees, in part by having a social mission and purpose for the business; improvising and adapting to find ways around tough problems, illustrating the principle of jugaad; and coming up with creative value propositions to meet the persistent needs of long-term customers. Here we see how India Way companies turn those principles into strategies that give them a competitive advantage in the marketplace.

Assigning Priorities

Time might not be money, but its allocation tells a lot about what people value. We offered Indian business leaders a list of tasks typically considered important for top executives, and asked them to rank the tasks in relative importance based on how much time they devoted to each. The rankings by Indian business leaders are shown in table 5-1. We also asked the top human resource executives in the same companies to answer the identical question about their chief executives’ priorities. Those answers were virtually identical; the only difference was an inversion of items 3 and 4 in table 5-1.

Indian business leaders’ priorities

| 1. | Chief input for business strategy |

| 2. | Keeper of organizational culture |

| 3. | Guide or teacher for employees |

| 4. | Representative of owner and investor interests |

| 5. | Representative of other stakeholders (e.g., employees and the community) |

| 6. | Civic leadership within the business community |

| 7. | Civic leadership outside the business community |

Strategy among the Indian corporations we examined was deeply rooted within the firms, supported by a set of attributes and practices that helped drive their strategies. Building strategy meant building these capabilities and stressing alignment within the organization, ensuring that many separate practices were consistent with one another and mutually reinforcing. In this context, being the “chief input into the strategy process” did not imply that the executives were meddling in a staff function. It suggested instead that they were monitoring and maintaining the infrastructure of their organization, the firm’s architecture and culture.

The difference with Western, and particularly American, priorities is substantial. Chief executives in publicly held American companies usually hold maximization of shareholder value as their most important priority. Shareholders for Indian executives were almost always well down the list—below the company’s customers, below the company’s employees, and below the broader Indian society. No Indian business leaders in our conversations placed shareholder value as the top company priority or advanced the view that investors were the most important stakeholder, a notable omission given that many of executives were major holders of their company shares.

Percentage of Indian business leaders identifying leadership capacities as critical

| Question: “What are the top two leadership capacities most critical to your exercise of leadership over the past five years?” | |

| Leadership capacities | Percentage of executives |

| Visioning capacities: articulating, envisioning, strategic thinking, change | 61 |

| Architecture and culture capacities: organizational structure, core values | 43 |

| Individual capacities: inspirational, accountable, entrepreneurial | 57 |

| Human capital capacities: talent selection, grooming, alignment | 52 |

| External capacities: understanding competitors and markets; outside relations | 22 |

| Note: Percentages do not add up to 100 because participants listed all the capacities they thought were most significant. | |

What the Indian business leaders were interested in, decidedly, was creating strategy. When we asked Indian business leaders to identify the two capacities that have been most critical to their exercise of leadership over the past five years (see table 5-2), they placed their greatest stress on four internal capacities—visioning, architecture and culture, personal qualities, and human resource issues. This suggested that the leadership capacities they saw as important were connected to the development of enduring capabilities for the future.

Organizational Architecture and Culture

Strategy can only be executed in a suitable organizational architecture and cultural context. The relationship between strategy and organizational architecture has been studied in detail in the United States context. In his 1962 classic of American business history, Strategy and Structure, Alfred D. Chandler explored how large U.S. corporations had emerged during the twentieth century. Focusing in great detail on four icons in four industries—DuPont in chemicals, General Motors in autos, Standard Oil in petroleum, and Sears, Roebuck in retail—Chandler concluded that the rise of the corporate form could be traced to inventive strategies and wellaligned corresponding structures. Leaders of the big four had adopted a clear and comprehensive business strategy and fashioned a customized organizational architecture to support it. That formulation remained much the American business hymnal for the remainder of the twentieth century and even the start of this century.2

Strategy drives structure, in Chandler’s formulation, and the Indian business leaders we interviewed were in wholehearted agreement. But for achieving their strategy, they viewed two key components of structure—the organization’s architecture and its culture—as vital foundations to be created, built, nurtured, and certainly not taken for granted. Many of these leaders spoke from long and arduous personal experience: they had been forced to create organizational architecture and culture out of whole cloth because so many of the fledgling businesses they launched or acquired initially had so little of either.

For executives working at well-established American firms, the divisions and layers and mind-sets that they inherited on joining the company had been fashioned years or even decades earlier. The health-products company Johnson & Johnson, for instance, dates to 1887. Its well-known “credo,” a 303-word statement that has helped define company culture since being crafted in 1943 by founding-family descendent Robert Wood Johnson, is carved in granite at company headquarters, as Abraham Lincoln’s 273-word Gettysburg Address is carved in marble on the Lincoln Memorial. And just as young Americans are sometimes called upon to memorize the Gettysburg Address—or feel impelled to do so—so new Johnson & Johnson employees master the credo.

Though Indian civilization is ancient—the Indus Valley Civilization dates back to 2600 BC—few of India’s biggest companies carry a century-old lineage like Johnson & Johnson, General Electric, or J. P. Morgan. Indeed, of the dozen largest Indian companies, as measured by the Forbes Global 2000 Ranking for 2007, only two—the State Bank of India (1806) and Tata Steel (1907)—have ancestries that predate independence from Great Britain. The thirty-four largest Indian companies on the Forbes annual list have a median founding year of 1955, compared with 1888 for the thirty-four largest U.S. companies.

Especially in the technological fields, many Indian firms are so new that their founding figures are still the presiding executives, and they have had to invent their own architecture and culture along the way. That required extra work, but as we saw in earlier chapters, it also liberated Indian business leaders in many cases from the burdens of legacy structures, whether in personnel practices or in the company pyramid, though it should be noted that state-owned companies and some in the extractive sector did carry forward preexisting structures and union histories. But in less than two decades of economic liberalization, many Indian firms have had to invent their own new structures to work with their fresh ways of creating value.

Freed of the need to accommodate new conditions to old structures, companies were able to evolve organization and strategy as conditions dictated. This was especially valuable for some of India’s most rapidly growing companies in newer industries: Wipro, for example, with a workforce of more than 72,000 in 2008, up from 14,000 in 2002 (greater by a multiple of 5.1); Bharti Airtel with 25,000 workers, up from 3,400 in 2002 (a multiple of 7.4); and Infosys with 94,000, up 10,700 in 2002 (a multiple of 8.8). Even some traditional manufacturers had displayed pronounced employee growth. Tata Steel employed 84,500 in 2008, nearly twice its workforce of 46,350 only six years earlier, at a time when the steel industry in most countries had been in sharp decline. In most cases, organizational architecture and company culture—far from being drags on growth (as per American giants like General Motors)—had come to be deemed the vehicles through which their leadership of and strategy for their fast-expanding firms could be extended and exercised.

A Committed Top Tier

Indian business leaders viewed building their top tier of managers as the single most important component of company architecture. A set of able, energetic direct reports was viewed as key, and most important of all was a commitment to the company’s vision and strategy.

Executive chairman Mukesh Ambani of Reliance Industries said that building a “transformational business model” was the first step in structuring his organization, but with that in place, “aligning the leadership team to have loyalty to the vision is the next step.” It was “very important,” he explained, “that everybody understands the execution pieces and stays on the same page. Especially in a fast-growth economy like India, where talent has huge amounts of opportunity, it is important that we create loyalty to the cause.” And then he added a thought rarely heard among western CEOs but commonly expressed within his Indian peer group: “For us, it has always been that the cause is much greater than making pure financial returns.”

Once the top team was in place, business leaders emphasized the importance of pinpointing responsibilities, providing the resources to perform, and then holding team members responsible for results without micromanaging the process. For S. Ramadorai, managing director and chief executive officer of Tata Consultancy Services Ltd., for instance, empowering his staff has been vital to aggressively growing his company. A. K. Balyan, executive director of Oil and Natural Gas Corporation, reported that as a result of the “highly decentralized decision-making” pyramid that he had created, his “key executives have to function as virtual CEOs of their divisions.” Fewer decisions come up to the chief executive since key executives take on their own decisions and are empowered to make them.

No Risk, No Reward

If product and service decisions were certain and risk-free, there would be no errors, but since the tumultuous Indian environment was anything but certain, Indian business leaders “have a much higher capacity to handle ambiguity in business situations,” in the words of Motor Industries Company Ltd.’s (MICO) M. Lakshminarayan, and thus “are very, very flexible in handling” problems.

The executive chairman of Shree Cement, B. G. Bangur, told us he considered creativity so critical to his company’s competitiveness that he had been explicitly working to ensure that his managers were comfortable with a certain error rate in their decisions. “If managers feel that failures will be a blot on their career, then most of the [innovative] projects die down because they want a very high rate of success.” In “our company we are saying that innovativeness in itself is success, whether you proceed and the project succeeds or not.” When a new project does not pan out, he said, “we never say it is a failure. We still say that we have learned one more way how the things will not work, and start all over again.”

For Zee Entertainment’s Subhash Chandra, decentralization of decision making and a tolerance for decision error had become building blocks of his company’s culture. “So far we have been a very entrepreneurial group in which we did not have the corporate hierarchy or divisions or that kind of a thing,” he said. Managers are encouraged to call executives for decision approval in the middle of the night, but they are also “encouraged to take decisions by themselves, without any kind” of formal authorization. That has been “the competitive advantage of our building the business so far,” Chandra said. When managers make a decision “that has resulted in losses, they have never been punished or asked to leave the job.” But, he added, “We do say, ‘Hey, don’t repeat the same mistake.’”

Pushing Decisions to the Front Lines

At some companies, tolerating errors in the name of risk taking was coupled with an architecture that pushed decisions out from under the shadow of headquarters, right into the hands of frontline employees. Nakul Anand—chief executive for the Hotels Division of ITC Ltd., one of India’s largest conglomerates, with interests in food, agriculture, and tobacco—had come up through the organization and knew from personal experience how stultifying the hierarchy can appear from below. His aim as division chief, he said, “had been really to make headquarters not a control body but the ‘help desk’ because the biggest competitive advantage are the ideas that flow from the field.”

Ajai Chowdhry, executive chairman of HCL Infosystems, India’s largest personal computer maker, likewise looked to his operating units for the formulation of competitive ideas. At monthly meetings of the heads of all the HCL businesses, Chowdhry observed, “we don’t discuss numbers, but we discuss breakthrough objectives.” For such meetings, he said, “each and every part of the business is encouraged to come up with its own new breakthrough objectives and strategies for this year and the next three to five years.” Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw, chairman and managing director of India’s first biotechnology start-up, Biocon, had built risk taking into her company’s culture through her own modeling—consistently pursuing biotechnology commercialization opportunities that looked exciting but also very risky.

From Risk to Speed

When uncertainty is high and risks abound, decision making can slow down due to fear of irreparable errors or career-ending blunders. To balance out that equation, several companies stressed the importance of timeliness in decision making. In the words of Anil Khandelwal, chairman and managing director of Bank of Baroda, “I think speed itself is a competitive advantage because I am competing with twenty-seven public-sector banks. Speed should become a competitive advantage—my capacity to do things faster, to execute faster, to come out with new products faster.”

The delegation of authority, devolution of responsibility, tolerance of errors—all built into a culture of frontline risk taking and innovation—brought disadvantages too, many of the Indian executives warned. Managers in such a regime acquire a built-in permission to make decisions that might not be fully in compliance with the company center, and inept or rogue managers can make a mess of things. On balance, though, most of the Indian business leaders had concluded that the decentralization of decision-making authority had become an essential foundation for making risky decisions in India’s inevitably unpredictable and fast-changing environment—a step, we should note, that is becoming the global norm in a flattened and competitive marketplace. Rather than India’s business norms converging on traditional Western standards, odds are that Indian methods are already where the world is now heading.

Customer Centricity, Indian-Style

Like their Western counterparts, Indian business leaders talked of a laserlike focus on customers, but with a subtle national twist. Traditionally, market-driven business strategy relies on research to identify the best customers who offer the highest profit margins, and the goal of companies is to move in that direction. The India Way companies took a very different approach. In many firms, leaders relied instead on their company’s culture to focus employee attention on customer service.

Consider, for example, the experience of Kishore Biyani, managing director of Pantaloon, India’s largest retailer, with more than a thousand stores across the country. The culture at Pantaloon asked all employees to put themselves in the shoes of grassroots customers and imagine the company and the shopping experience from their perspective, not just as potential buyers but as potential Indian buyers.

“Our biggest competitive advantage,” he said, “is our sense of Indianness in whatever we do, because we believe in India as a very different country, emerging in a different era.” He sought to foster “everyone’s ability to think as a customer at the caste and the community level.” The practical result had been to develop retail outlets (under names like Blue Sky, aLL, and Top 10) and products that were closely tuned to the interests of various segments of Indian customers and unlike the merchandising of their international competitors. Pantaloon worked “on the Indian ethos and Indian values,” he concluded, “and all our promotions are very Indian-like.”

Biyani’s emphasis on tailoring company culture to a specifically Indian market might seem like nothing more than an old chestnut—Who is against fostering company culture? Who does not want to meet their customers where they live?—but once again, the difference is a matter of degree, not kind, and it emerged as one of the more striking thematic differences.

Moving Sideways

The intense focus on customers carries a corollary. A company’s direction is set as much by what works with customers as by a preexisting strategy for what should work. Rather than moving linearly forward, then, many of the executives reported that they move more sideways. ICICI Bank’s deputy managing director, Nachiket Mor, expressed the concept well. “We are not great strategists,” Mor offered bluntly. “If you were to ask me, did we know in 1996 what we were going to do in 2006, I would say we hadn’t a clue. With hindsight we could always construct a story, but by foresight we hadn’t a clue. And if you were to ask me where we are going to be in 2016, other than describing it in kind of general terms of asset size and capital base and all of that, I wouldn’t be able to give you a more precise answer.”

Indeed, ICICI’s trial-and-error approach isn’t the sort of strategy a traditional consulting team is likely to recommend. Rather than moving linearly toward a preordained set of objectives, the bank has sidled into adjacencies where opportunities seemed to open. For that, ICICI needed more than a grandiose business plan; it required executives who could see and then seize those possibilities. The big objectives of fast growth and full services were clear; getting there was anything but.

Strategic planning for a distant future was sure to be quickly outdated by the market’s rapid progression, Mor explained. In “complex environments like India, where you know the environment changes fairly dramatically and fairly quickly,” there’s little benefit to “extremely long-term thinking.” His time frames for building and judging company programs ranged from three to six months, not twelve to eighteen. “The animal I like to compare ourselves with is more like a crab rather than a tiger or a leopard that moves quickly towards a very prespecified destination. We move sideways because the environment is too uncertain; it evolves too rapidly.” The bank did not spend much time, he said, “agonizing about core competency and what is the purpose of our business,” but it moved instead to simply and quickly “seize the opportunity.” The sideways movement was a product of necessity. “If you try to build a long-term plan around a certain model of the customer,” he warned from experience, “it is possible it could be completely wrong.”

The bank’s mind-set and pay scheme reinforced this thinking through an internal rewards system “geared towards people who can quickly spot immediate opportunities and capitalize on them. There aren’t a lot of rewards for people who do long-term strategic thinking. We are just much more short-term people.”

Given twenty potential initiatives for ICICI, Mor would try all twenty rather than bet on what seemed the best two or three. His preference was to “fail fast” and discover through trial and error what succeeded, logic Mor put to work in building a microfinance capacity for the bank. The plan was to expand rapidly—from 20,000 clients to 4 million clients and from a million dollars lending to a billion dollars in only three years. Mor tried a host of tactics at the same time: opening branches, partnering with nonprofit organizations, even buying another bank. Since most of the clients were borrowing for the first time, he had “no idea what they would do when given the money”—whether, for example, they would want health insurance or need rainfall guarantees. In general, he observed, it was “completely unknown territory.”

Not knowing precisely what the microfinance customers really needed, Mor sought to create a bank presence no more than 10 kilometers from any rural customer. Poor decisions were made, but they tended to be tactical errors. “There are clearly things that we did wrong,” Mor told us, “because we focused on what we saw rather than on what we might have seen.” At the same time, investors were relatively unconcerned about the sideways approach, giving the bank leeway that would be rare in the United States. Both domestic holders and international funds sought to understand how the top management team, and the CEO in particular, operated, but the lack of a specific strategy or a long-term plan did not seem a vexing concern for investors so long as they heard a company story that made sense and produced year-on-year double-digit growth. Much the same had been true of the bank’s relationship with its regulators.

Unlike in American management models, product decisions may have been opportunistic, but continuity was built into enduring relationships among ICICI executives. “American companies don’t really have long-term executives,” Nachiket Mor told us. As a result, “relationships with their own company, and therefore with the rest of the world, seem very transactional, very much day to day.” By contrast, in India, “we are going to be dealing with [the same] person for the next ten years, so no conversation is just one conversation.” Consequently, in dealing with a subordinate, colleague, or superior, personal anger and harsh language are best avoided, as are any actions that can cause humiliation or a loss of face. And indeed, long-term supportive and trusting relationships among the bank’s executives have proved an essential ingredient to its sideways strategy.

Innovative Structure and Strategy

Taken together, organizational architecture, company culture, and competitive strategy lie at the operational heart of the India Way. And they do so in ways and combinations that creatively respond to the market conditions and opportunities at home and abroad.

In some industries, such as information technology services, Indian firms created competitive organizations with operations based in both India and the countries of their customers. Firms such as Infosys, Wipro, and Cognizant Technology Solutions Corporation emerged as global organizations that happened to originate in India. In wireless telephone services, several Indian firms leapfrogged several generations of technology to adopt the latest mobile telephony and designed lean organizations to provide quality service at far lower costs than their counterparts in developed countries. Innovative mobile-phone firms such as Bharti Airtel and Reliance Infocom, though largely focused on the Indian market at the outset, invented new strategies that could work for companies in any geographic setting. Although Bharti Airtel was an early mover into mobile telephony, it was a later entrant, Reliance Infocomm (now Reliance Communications) that revolutionized the mobile telephony market by investing in a new network and bringing down the price of a local call to “less than what it cost to send a postcard,” the exhortation of Dhirubhai Ambani to his sons Mukesh and Anil. Bharti Airtel and others had no choice but to respond, and the low-cost mobile market in India took off. Still another set of firms found ways to service the needs of the vast Indian market by capitalizing on low-cost production and catering to the specific needs of underserved domestic groups. As noted earlier, Tata Motors developed a “people’s car” with very high fuel efficiency and extremely low cost to reach the subcontinent’s millions of motorcycle, scooter, and bicycle riders.

To appreciate the innovative combinations of strategies and structures among the companies led by those we interviewed, we focus on three pioneering approaches: Bharti Airtel’s groundbreaking reverse outsourcing of its mobile-telephone network; Cognizant’s development of information technology services with an onshore quality and offshore price; and Hindustan Unilever’s adoption of rural self-help groups to promote fast-moving consumer products in the countryside.

The three company studies below each illustrate how strategy comes from the principal practices of the India Way described in chapter 1: Bharti Airtel illustrates improvisation and adaptability, Cognizant demonstrates the importance of creative value propositions, and Hindustan Unilever shows the role of mission and purpose.

Bharti Airtel: Reverse Outsourcing for Scale and for Speed

If America’s perception of Indian business is defined by any single image, it surely is of rows upon rows of young Indians populating customer call centers in Bangalore and elsewhere in the subcontinent under contract with American companies, including some of the great technology names such as Apple, Dell, IBM, Intel, and Microsoft.

The 2006 U.S. film Outsourced opened with the manager of a Seattle-based call center learning that his entire order-fulfillment department was being outsourced to India. Adding insult to injury, the newly displaced manager was asked to visit India to help the replacement operation get on its feet. Indeed, American business outsourcing to India—now well beyond call centers, to encompass architectural drawings, legal briefs, equity analysis, even medical diagnosis—has been a growing feature of cross-border business for more than a decade.

In 2004, though, Bharti Airtel turned that pattern around—via what the Wall Street Journal termed reverse outsourcing—to solve an architectural problem occasioned by its explosive growth.3 Sunil Bharti Mittal founded Bharti Telecom Ltd. in 1996 and later renamed it Bharti Airtel. He and his company caught the wireless wave in the early part of the decade and rode it to become the country’s largest telecom-service provider, with 75 million customers by late 2008—and an expected 125 million by 2010. Along the way, however, Sunil Mittal concluded that he simply could not ramp up the organization fast enough to meet its accelerating customer demand. Nor did he feel that, as a “very, very hands-on” manager, he would be able to effectively lead a far larger enterprise properly. At the same time, Mittal was facing formidable competition from archrival Reliance Infocom. His solution to surviving the multipronged challenges facing his company: concentrate on the top line, act fast to secure an early-mover advantage, and swallow the risks that always come with speed.

“One of the burning things in my story has been [to grow] the top line as fast as you can,” he said. “I have always believed that bottom line will come if there is a top line.” As a result, “speed and always speed has been what we have done: launch things in the marketplace, get ahead of competitors, be there, get the market share, get top line.” Moreover, “given that we had very limited resources, we did not have the luxury to spend too much time on the drawing boards and fine-tuning what we were doing.” If “you are caught between speed and perfection,” Mittal urged his managers, often to their surprise, “always choose speed.” Manoj Kohli, who became Airtel’s CEO in 2007, added, “We will always be a start-up venture in our mind in terms of our hunger [and] passion to win in terms of agility.”

Winning by Losing

To achieve both scale and speed, Mittal shocked the telecommunications industry in 2004 by farming out the operation of his entire phone network in a $400 million contract to Ericsson, Nokia, and Siemens. He would no longer have to acquire and maintain equipment. He would instead simply pay a lump sum to the European vendors, according to the traffic they handled and the quality they provided. He also contracted out most of Bharti Airtel’s information technology services, ranging from customer billing to the company’s own intranet, in a $750 million deal with IBM. So comprehensive was the outsourcing that it left virtually no IT staff on Bharti Airtel’s payroll—though information technology is the very foundation of wireless telephony—and even Mittal’s own desktop computer was given over to IBM management.

Mittal appreciated the risk in outsourcing his firm’s core capabilities to larger and more powerful multinational companies. But he viewed the contracting firms as “the Rolls-Royces of the industry,” and in any case he had signed outsourcing contracts for renewable two-year periods with exit clauses if the providers ever turned “rogue.” He also concluded that the forecast growth of Bharti Airtel’s subscriber base was so great that the incentives for Nokia and IBM to continue their mutually advantageous relationship with Bharti would outweigh any temptation to exploit Bharti Airtel by withholding new equipment or ratcheting up fees.

Mittal also met directly with the IBM chief executive because of the risks involved, and the IBM CEO assured Mittal that he would personally monitor the project. Our “partners are actually a very, very important part of our future,” Manoj Kohli said, and “therefore being respectful of them, being transparent with our dealings” with them, “and of course having full faith in them is important.” The new arrangement also required fast creation of a capacity to both oversee and collaborate with their partners, which Kohli frankly admitted they did not have at the outset.

Radical Outsourcing

Beyond doubt, Bharti Airtel’s outsourcing moves defied conventional logic. Since core competencies are widely viewed as the value drivers of a firm, peripheral functions ranging from property management to employee benefits—so goes the reasoning—could, and should, be handed over to other firms for which such functions are their core competencies. But in outsourcing its telephone network and customer infrastructures, Mittal appeared to be placing Bharti Airtel’s value drivers outside the company. “People gasped in horror,” he told a reporter. “I got calls from around the world saying, ‘You’ve gone nuts! This is the lifeline of your business, something you can’t afford to lose!’ ”4

A major European CEO telephoned Mittal to warn, “You’re giving your life, the very heart of your business, into the hands of outsiders. You’ll regret this because nobody has ever done it and nobody will ever do it.” In response, Mittal noted that, while Bharti Airtel so far had hired only 237 people into its information technology operation, the company of the caller employed 8,000. Mittal suggested to the European executive that his 8,000 staffers would never allow him to outsource his IT function even if he wanted to do so later on. But Mittal could still do so now given his far smaller number of IT staffers, and swift outsourcing was necessitated in any case, Mittal concluded, by the imperative of scale and speed.

Managing Rampant Growth

As Sunil Mittal explained to us, a key driver in his reverse outsourcing was the constrained human resource position in which the company found itself as it was rapidly ramping up. Bharti Airtel’s initial “in-house” business model had been targeting 25 million customers, but after comparing his company’s operations with the few companies worldwide that were already servicing 25 million customers, Mittal doubted he could build the structure fast enough to service that large a base.

“We clearly saw that the way we were structured and the way we operated would not allow us to satisfactorily come to that point.” With few employees and a still modest user base, you could “practically run the company the way you wanted,” he said, but hiring the 30,000 employees he estimated to be requisite for servicing 25 million customers required a far larger and more complex structure.

Even worse, Mittal anticipated reaching 75 million to 100 million users within several additional years. In some months, Bharti Airtel was already signing up a million or more customers. Airtel could not have hired, he concluded, the more than 10,000 required employees technically trained in network and information technologies and then retain them, since other companies, like Infosys and Wipro, were also exploding in size and were often proving to be more attractive destinations for engineers than Bharti Airtel. After meeting with several large European mobile-phone companies, including Vodafone and T-Mobile, to learn how they operated, Mittal told a reporter, “I saw that these were huge companies, hugely resourced. And it began to dawn on me: I have to be like them. But could I afford to be like them? Did we have the resources to do that? Were we the best company to attract that kind of talent? The answer, clearly, was no.”5

Moreover, it had become a convention in the Indian telecom industry to build out 30 to 40 percent excess capacity on any new network to anticipate further short-term growth. Given its burgeoning scale, that meant that Bharti Airtel would have to spend another $300 million to $400 million over the next several years to create its extracapacity networks. Worse, Reliance Infocom, the brainchild of Anil Ambani, planned to enter the cellular market, and Mittal feared that it would choose to jump-start its services by offering extremely low rates that would have been “unthinkable” until then. Because such rock-bottom prices posed the potential of slowing or even shutting down Bharti Airtel, Mittal recalled, the possibility sent “shivers down the company’s spine.” Time was in short supply, too: “Given that we had about eighteen months to figure this out and compete with Reliance, we had no time to induct ten thousand people, train them, and make them think our way.”

Innovating on the Value Chain

To compete on price, Bharti Airtel would have to ensure that its cost structure was held tight and would not inflate with customer growth. To compete on time, the company would also have to find some way of radically expanding in an extremely competitive labor market for telecom specialists. Thus, Mittal turned to reverse outsourcing to keep Airtel’s up-front investments low, since he would not have to build more capacity than it needed at the moment, and to keep its recruitment at realistic levels, since it did not have to find the thousands of engineers who would otherwise be required. By circumventing capital spending and hiring constraints, Mittal found he could then focus the company on understanding customer preferences, regulatory barriers, and emerging markets, ranging from BlackBerry service to digital television.

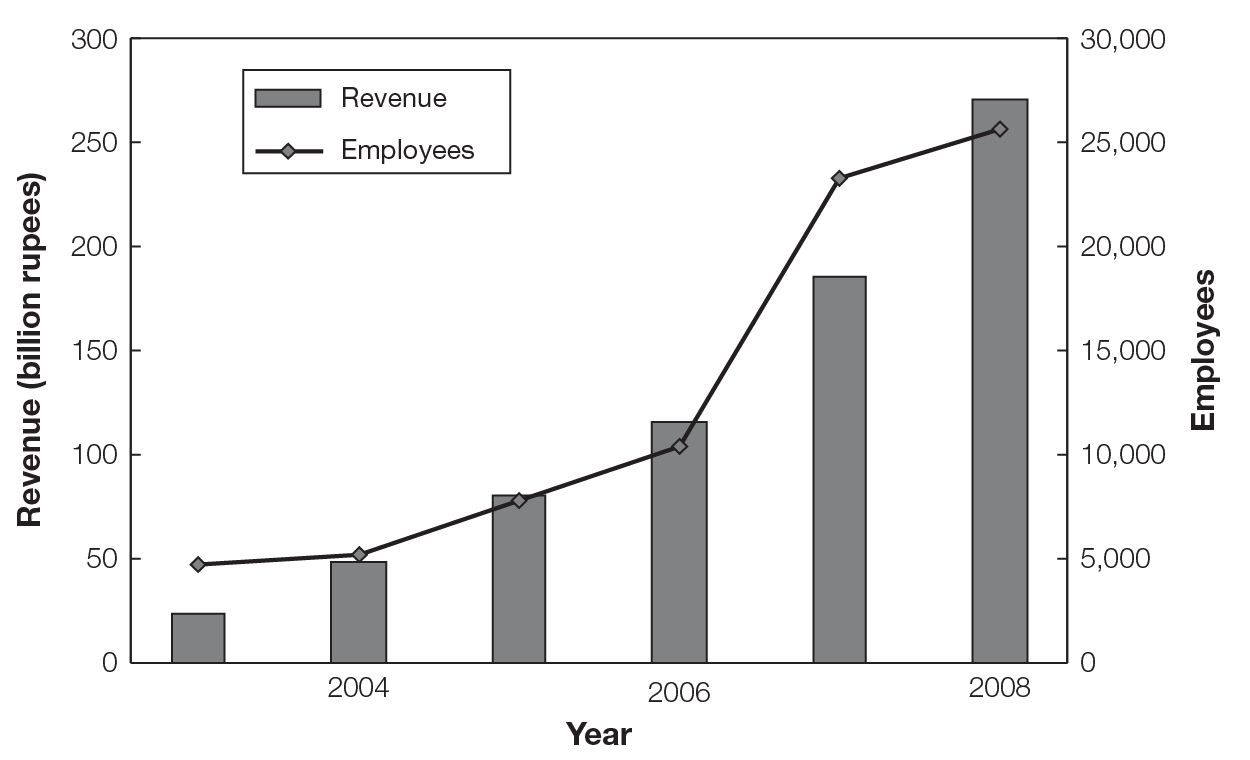

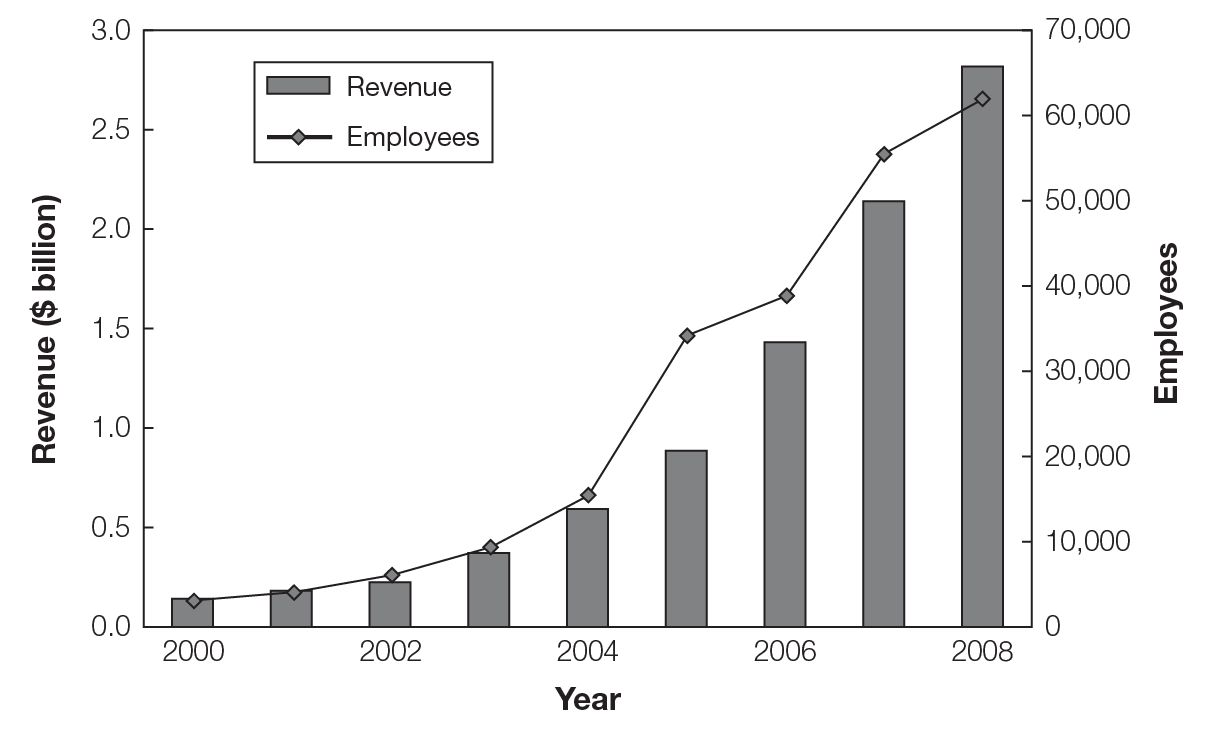

As shown in figure 5-1, the result borders on a miracle: the company slowed its own hiring without retarding its customer expansion, making it India’s number one telecom provider by 2008, with more than 75 million customers, up from none a little more than a decade earlier. With revenues of $6 billion, Bharti Airtel had come to lead the pack in the Indian wireless industry, outselling its closest (and once feared) competitor, Reliance Infocom, by over 40 percent. Airtel alone accounted for more than 40 percent of the Indian wireless market share and nearly 60 percent of the market capitalization of the country’s telecommunications service industry.

Improvisation and Adaptability

Bharti Airtel’s massive reverse outsourcing brought another, more personal advantage, Sunil Mittal confessed. He and his brother, Rajan Mittal, also in top management, used to sit down during the company’s annual budget review to decide how much to allocate to network and information technology. The “techies” already on board were “just making us look silly in those discussions because we were both incompetent to discuss those issues,” Mittal said. Contracting with the outside parties eliminated the necessity of having to endure such an unhappy annual budgeting ritual. Even more important from his point of view, outsourcing meant he could still run the company in a hands-on fashion.

Unable to build an organizational structure of the usual kind that would properly service the strategy that he was bent on pursuing, Mittal transformed his strategy and organization, opting to create value and defeat rivals through company brand and customer relations rather than through his own technologies. Improvising and adapting along the way, he proved that sometimes structure is not determined by strategy, but quite the opposite, with organizational constraints resulting in a redefined strategy.

Cognizant: Creative Value Propositions for New Customer Segments

One of the more ironic claims of modern management is the solemn declaration that a company is about to become client focused or even customer centric. After all, are not companies defined by providing a service or product that clients and customers want and are willing to purchase? But the claim, of course, is a matter of degree and of company structure, whatever the strategy.

Consider Cognizant Technology Solutions Corporation. Initially created as a division of American parent Dun & Bradstreet (D&B) in 1994, Cognizant got on its own feet in 1998 with an initial public offering and a shot in the arm from a surge of Y2K work at the turn of the century. By 2008, this U.S.-listed and -headquartered company with a sizable Indian back-end operation supported mainframe computers and client servers at more than five hundred organizations worldwide in industries from banking and insurance to manufacturing and retail. Among its clients: Aetna, Citigroup, MCI, and RadioShack in the United States, and France Telecom, Nestlé, Nokia, and SAP in Europe.

Life, though, was not always so good. At the start of the decade, Cognizant faced a fiercely competitive global landscape. Some seven hundred Indian-based companies were providing information technology outsourcing services, many at rock-bottom prices. At the other end of the spectrum, the American “Big 5” system integrators—Accenture, BearingPoint, Capgemini Ernst & Young, Deloitte, and IBM Global Services—provided greater value-added services at higher prices. Lakshmi Narayanan, then chief operating officer of Cognizant and later chief executive, and Francisco D’Souza, a fellow executive and later also the CEO, opted to create a structure that in effect combined first-class service with rock-bottom fees. “We wanted to give the customer a Big 5 experience at an offshore price,” explained D’Souza, an example of a creative value proposition that is at the heart of the India Way.6

Onshore Service, Offshore Cost

The first important decision Cognizant made was to steer away from acquiring new customers. The alternative strategy was to develop deeper relationships with fewer customers. To pursue that end, Cognizant converted the concept of global outsourcing into a combination of on-site service and international work. Cognizant jettisoned the conventional model of Indian IT outsourcers with headquarters in India and satellite offices near client locations in the United States and elsewhere. Instead, the company opted to be headquartered in New Jersey. Narayanan explained: “We felt that since there are a number of India-based companies who are providing these services, to differentiate ourselves we’ll flip the model and be closer to the customers that we serve.”

To reinforce the U.S.-centeredness, he listed the company on NASDAQ and hired many people in the United States. At the same time, he kept Cognizant an essentially Indian company, with the bulk of its software engineers and other employees still working on Indian pay scales. Of its 60,700 employees at the end of 2008, up from a handful in 2000, more than 70 percent were still based in India, including three-quarters of its engineers (see figure 5-2).

Cognizant Technology Solutions Corporation, annual revenue and number of employees, 2000–2008

Source: Company records.

Compared with its Indian competitors, Cognizant’s initial margins were thinner because it delivered more premium services, but over time that served to build enduring rather than spot relations with clients, relationships that in turn became a driver of sustained growth. Rapid expansion in turn became a magnet for quality talent. “When we go to market and hire talent,” said Narayanan, we “emphasize that we are the fastest-growing company. ‘If you come to our company, you will grow faster than anywhere else.’” The result, according to Narayanan: Cognizant was able to attract “the best and the brightest talent,” and the superior talent meant superior service.

The Charlie’s Angels Dilemma

Cognizant also devolved more power and responsibility into the hands of the managers who were geographically closest to its customers. This was required by the market, Narayanan explained, because sourcing projects was becoming more complex, requiring more sophisticated and responsive contracting managers who appreciated the industry’s and clients’ unique requirements. Still, most of the work was performed by employees in India, and that created a new challenge for the customer-facing on-site managers. The latter were increasingly working late into the night—India is ten and a half hours ahead of New York and thirteen and a half hours ahead of San Francisco—to resolve issues with the Indian-based bulk of their teams. “It was a little bit like Charlie’s Angels” for the U.S.-based managers, recalled Francisco D’Souza. When “you wake up in the morning, a voice on the phone tells you what to do.”7

To reduce the “Charlie’s Angels” factor, the company created a new structure to bridge the time-geography divide, formally capturing what had already emerged informally. Cognizant instituted a “comanager” scheme in which two equally responsible managers led the sourcing team, one close to the customer and one close to the employees in India. Though separated by more than ten time zones, the comanagers were held equally to task for services results, customer satisfaction, and project revenue. The joint leadership deliberately ran against management orthodoxy positing that responsibility should be pinpointed in a single office, and Cognizant watched to make sure that the traditional tenets did not get in the way. With a new development office in Shanghai, the company even began experimenting with “three in a box” teams, with equally powerful managers at the client site, in India, and now in China as well.

At the same time, Cognizant sought to build a “global mind-set” throughout the company to support its international strategy, with new customers coming from outside India and the United States. “We changed the model,” explained Narayanan. “We started expanding into Europe. One of the key things that we learned during our formative years working with D&B was to get a global mind-set,” which required us “to think about people, to think about anything that we do from a global perspective and not specifically a U.S. perspective or an Indian perspective.” To drive a broader perspective deep into Cognizant’s makeup, the company recruited managers from many countries and assigned them to work in many other countries. In Narayanan’s view, this became a key competitive advantage for the company.

Bringing the Board on Board

The company also built a culture that placed a premium on intense and enduring relations with customers. Part of that strategy involved turning away a certain number of prospective customers in favor of deepening partnerships with existing clients, and that in turn proved to be a platform for lateral expansion. “If you have delighted your customer, they will be willing to try you out in other areas, which means they will buy other service areas and other products that you produce,” Narayanan told us. “Customers participating in industry seminars will say, ‘We have succeeded in partnering with Cognizant, [and] I would encourage you to partner with Cognizant.’”

So strong had the culture become, that Cognizant’s board of directors increasingly wanted to hear about customer satisfaction and retention rates rather than revenue growth and profit figures. The directors could see that those two parameters drove the firm’s financials, and they sought to know more. As Narayanan told us, “We have a unique event every year [where] we review the strategy of the company, and the board invites certain customers to come and participate and give the board and the senior management team direct feedback. They spend some time exclusively with the board and tell us, should we continue on the strategy, [or] should we change the landscape?”

Cognizant’s strategy drove its structure, but with a pioneering twist. Differentiating itself from both high-end outsourcing providers in the United States and low-end providers in India, it sought to combine high-end services with low-end costs, creating in the process an appealing value proposition. But to achieve that seemingly contradictory duality, it devised a bifurcated architecture that invested coequal authority in two managers, one outward facing and the other inward managing, and it instilled a culture that channeled energy in both directions. Together, they provided for an innovative way of creating value and “allowed us to extend the business model for the changing business environment,” D’Souza concluded.8

Hindustan Unilever: Architectural Innovation and Creative Value Propositions

One of the unique aspects of the India Way has been the capacity of the nation’s business leaders to find a competitive advantage where no one else was looking. They have often built and followed radically different structures and strategies than the Western norm, yet the practices that have flowed from those decisions have frequently proved applicable to business in other markets. Hindustan Unilever’s Project Shakti, a system for selling products through rural self-help groups, is another case in point.

Out of the 4 billion people on the planet who make less than $2 a day, more than 750 million live in India, four-fifths of the populace.9 The dominant assumption among large corporations is that the bulk of the India population has no purchasing power and thus does not represent a viable market. Although this assumption is largely incorrect, as C. K. Prahalad argues in The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid, the problems of accessing this enormous but mostly latent customer base are still huge.10 Nonetheless, this was the challenge Hindustan Unilever (HUL) took on with Project Shakti.

In one sense, it was only natural for the company to do so. Hindustan Unilever is well known in India for its leadership in rural marketing, and its legendary brands and products are featured regularly in case studies at Indian business schools. What’s more, over the decades, HUL has not only greatly benefited from the economic expansion of India but also contributed considerably to the nation’s development. HUL has consciously woven Indian policy imperatives into the company’s strategies and operations, linking business interests with national interests. Doing so inevitably has caused the company to look past Western business models that use standard marketing and supply-chain practices. All that said, though, Project Shakti was a step beyond anything HUL had tried before.

Creative Value Propositions: Selling Beyond the Media’s Reach

Manvinder Banga, the former chief executive of Hindustan Unilever, observed that one of the greatest challenges for selling in India is that the conventional media reaches only half the population, thus leaving more than 500 million people largely in the dark about a company’s product or brand. The rural population is scattered in some 600,000 villages that are not connected to urban centers by newspapers, electronic media, rail, or even, in more than half the cases, by road. Consequently, companies that want to grow beyond urban and semiurban India to access rural customers have had to devise innovative ways to get their attention.

Enter Project Shakti, launched in 2000. (The name references strength, power, or empowerment in several Indian languages.) At the time, Hindustan Unilever was already engaged in price wars with Procter & Gamble in product markets such as fabric wash and personal care; the growth of urban markets was slowing; and the company realized that long-run survival would require opening new markets. To this end, it developed its Shakti initiative to reach fresh customers in the fast-moving consumer goods market where competition was most pitched. The concept was to draw upon women’s self-help groups that had already been set up by various nongovernmental organizations and rural agencies in India. Typically comprising ten to fifteen women from a single village, these self-help groups operated as mutual thrift societies. They would combine small amounts of cash toward a common pool. Microcredit agencies such as rural development banks would then offer additional funds to finance approved microcommercial initiatives.

Hindustan Unilever built upon this infrastructure by offering entrepreneurial opportunities for group members to sell HUL products directly to fellow villagers. Shakti entrepreneurs would borrow money from their self-help groups, apply it to the purchase of HUL products, and then resell them to their neighbors. Because most of the women in the self-help groups had no prior sales or business experience, HUL hired rural-sales promoters to coach the nascent entrepreneurs. For the first several months, the Shakti villagers were rewarded with cash incentives for making a certain number of home sales calls, regardless of the amount actually sold. HUL also arranged for local banks to provide the Shakti groups with microcredit, with the proviso that the first installment toward repayment of loans did not begin immediately. The company also worked with local government departments to build acceptance of Shakti as an economic opportunity benefiting the entire community.

Broader Social Purpose and Business Growth

With Shakti, Hindustan Unilever sought to achieve its dual objectives of social impact and business growth. The self-help-group entrepreneurs worked as social influencers, increasing local awareness and changing attitudes toward usage of various products, mostly those targeted for women. At the same time, Shakti provided sustainable livelihood opportunities for the rural women. Hindustan Lever first piloted the project in fifty villages based in the state of Andhra Pradesh, and it has since extended Shakti to fourteen other states, with forty thousand new entrepreneurs as part of the program by the end of 2008. By 2010, the company planned to recruit more than a hundred thousand Shakti entrepreneurs covering five hundred thousand villages, touching the lives of more than 500 million people.

By devising a new and self-sustaining channel for reaching Indian countryside masses, Hindustan Unilever has been able to open a new market for its long-standing products. Again, a creative combination of a new structure with a fresh strategy allowed the company to achieve what conventional wisdom would have doubted. Just as with Bharti Airtel’s reverse outsourcing, Hindustan Unilever’s Project Shakti made the counterintuitive intuitive. And in doing so, it contributed to a mission far broader than simply its own bottom line, providing fresh livelihood to large numbers of underserved women in the countryside.

From Strategy and Structure to Competitive Advantage

The leaders of Bharti Airtel, Cognizant, and Hindustan Unilever combined innovative strategies and structures that generated creative value propositions and unique competitive advantages. In the case of Airtel, Sunil Mittal brought a vision of providing very low-cost telecommunication services to a very large population of customers. And his value proposition was that a cell-phone call should cost little more than one cent per minute—at a time when the lowest cost anywhere in the world was more than ten cents per minute.

Though Mittal’s vision and value proposition were clear, he had no resources to build a structure to readily achieve them. This forced his radical rethinking of the capabilities of the firm and a transforming of the value chain. Instead of finding value in unique technologies, he would draw it from the customer interface. The resultant outsourcing of virtually all operations except marketing and customer contact proved an innovative model that yielded the lowest cost per minute for telephone service anywhere in the world. Airtel’s archrival, Reliance Infocom, was also able to achieve very low-cost mobile services, and together, they pioneered a new, transformative way of doing business. This resulted in explosive growth in the use of cellular telephones, catapulting India into the second-largest market in the world, behind China, with almost 350 million subscribers.

The Cognizant strategy also represented the delivery of a vision in which clients would receive high-end services for low-end costs, and it achieved that through introduction of its comanagement organization and creation of a global mind-set. Other rising firms in information outsourcing, such as Infosys, Wipro, and Tata Consultancy, pursued similar ends, but each sought to do so through its own distinct architecture and culture. By inventing new ways for moving into high-end services at low-end costs, Cognizant and its Indian brethren were able to challenge well-established global firms such as Accenture and IBM.

Hindustan Unilever executed a strategy based on a vision of delivering products to traditionally underserved populations, those of modest or little income. Hindustan Unilever’s Shakti project brought fast-moving consumer products to the rural poor through self-help village groups whose members would personally prosper from the process.

The common thread through all three companies’ experience was a leadership vision that stressed enduring service to established customers and long-term gain by solving the challenges of reaching hard-to-reach customers. The companies also built organizational capabilities that went well beyond the simple exploitation of their firms’ comparative advantage of low labor costs. Becoming competitive with large, seasoned firms based in advanced economies required the creation of a creative value proposition, innovation in the value chain, construction of appropriate architectural and cultural capabilities, and exploitation of distinctive aspects of the Indian environment.

Continued focus on the value proposition while building new capabilities—strategic use of technology, innovative architecture and culture, recruiting and developing talent—was not easy, and short-term results were often not quickly forthcoming. And here is where the distinctive holdings of Indian companies proved invaluable. A significant fraction of the ownership of these firms remained in the hands of the founding managers (as noted in the next chapter), and they were able to live with the trade-off of sacrificing short-term profits to long-term gain more comfortably than were leaders of publicly traded firms in the West.

Drivers of company strategy and competitive advantage in India

Figure 5-3 shows the forces and processes by which these and the other Indian executives whom we interviewed focused on building competitive advantage.

When we asked the Indian executives to identify key sources of competitive advantage in building their firms, their responses, displayed in table 5-3, pointed to the importance of three of the four major drivers of the India Way. Many of the business leaders stressed the importance of building their competitive advantage by combining several or all of these sources.

Adi Godrej, executive chairman of the Godrej Group, an industrial firm with interests ranging from precision equipment to food processing, explained that his company’s growth came from a simultaneous use of several foundations of competitive advantage. His group had emphasized a value proposition in the form of branding, an innovative value chain in the use of advanced technologies, and capability building in terms of business processes that the group had, in Godrej’s phrasing, “honed and developed over the years.” The Godrej Group had earlier also benefited from joint ventures with American companies such as General Electric, Procter & Gamble, and Sara Lee.

Sources of competitive advantages reported by Indian business leaders

| Question: “How have you built competitive advantage in your businesses?” | ||

| Source of advantage | Key elements | % |

| Holistic employee engagement | Transforming the organization; building the culture | 28 |

| Talent development; building the top team | 21 | |

| R&D/technological innovation | 19 | |

| Creative value propositions | Customer intimacy and focus | 36 |

| Improved differentiation | 24 | |

| Outsourcing, building supplier base | 23 | |

| Efficiency seeking, cost reduction | 23 | |

| Innovative value chain | 14 | |

| Broad mission and purpose | Vision, long term, transcendent | 24 |

| Sharing corporate and groupwide resources | 27 | |

Similarly, Azim Premji, executive chairman of Wipro, reported that his company had focused on delivering high-quality processes and services. He had introduced the management method of Six Sigma, which applies detailed statistical methods to the identification and elimination of errors; but he had also emphasized acquiring and applying feedback from his customers. “Customers love us most for our humbleness,” he said. “I believe, as a company, we listen carefully and are willing to learn.” By combining capability building with Six Sigma and a value proposition with customer focus, Wipro under Azim Premji had become one of the country’s leading technology-service firms, and a great personal and corporate success story. In 1964, at the age of twenty-one, Premji had taken over the small firm, then a vegetable oil producer, from his father. By the end of 2008, his company employed some 95,000 people in many countries.

Fresh Ideas, Long-Haul Thinking

Humility, innovation, counterintuitive thinking—none of them are guarantees of success, nor is present success a guarantee of future earnings. Circumstances change; operational steps have to be effectively executed. But when it comes to competitive advantage, large Indian companies are giving birth to fresh business ideas that combine a transcendent company vision, fresh value propositions for reaching new customers, innovative value chains for producing and distributing products and services, and a strong emphasis on building architectural and cultural capabilities for the long haul.

Like those in most national settings, Indian business leaders placed a premium on strategy. Yet they viewed strategy as a general set of enduring principles for competing, an approach to business that they deeply encoded in the architecture and culture of the company. Since so many of the executives had helped drive a meteoric growth in their firm—overseeing workforces at the time of our interviews that were sometimes larger by a factor of five or more, compared with those in the early part of the decade—they had come to view both architecture and culture as the necessary vehicles through which their leadership could be exercised and their strategy realized as their firms continued to expand.

The most important component of the architecture, the company executives said, was their top team, which they saw as an extension of their own leadership. The company culture constituted a further extension, allowing the executives to reach and align the thousands of employees on the payroll that they and their top team could no longer personally direct. Each company had developed its own unique blend of values and norms that defined its culture and its own unique way of organizing its work, but three distinctive themes in culture and organization stood out.

First, leaders emphasized a broader mission and purpose that enhanced both corporate agendas and development of the Indian market. Company leaders tended to downplay a focus on investors and shareholders, eschewing a short-term drive for quarterly results in favor of building innovative strategies and structures for longer-term growth, as evident in Hindustan Unilever’s outreach to the rural countryside. Second, company executives brought substantial innovation to the value proposition, as seen in Cognizant’s quality service at moderate cost. And third, the Indian business leaders emphasized holistic employee engagement with customers, a mind-set by which frontline employees would hear and provide what customers really sought, as shown by Bharti Airtel’s placement of mobile phones at low prices into the hands of millions of new consumers. This is the India Way.