As I mentioned previously, Ektachrome slide film is coming back, and soon a true tungsten slide film may again be available to stage photographers. That said, I’m not sure I could or would ever go back to the old days now that I’ve become enamored of some of my DSLR’s features, such as auto-bracketing and white balance. Ten years ago, digital photography wasn’t nearly as advanced as it is now, and I look forward to seeing where it goes in the next 10 years. I’m sure there will be great strides in terms of pixel count, ISO sensitivity, and maybe even the reduction of depth-of-field concerns. Focus and metering will certainly become more flexible and adept, and all of these wonderful new things will come with appropriate price tags attached. Until that time, we have some amazing technology available to us, and the potential to create exciting and vibrant images.

As I said, I don’t attribute my success to anything beyond a determination to work hard at gaining the skills needed to be fast, efficient, and competent during a photo-call. There are three things that you can do to rapidly improve your abilities and portfolio.

- Practice often.

- Immediately sort and evaluate your photos.

- Back up everything.

I’ve already mentioned several times the costs and time-lines associated with slide film. Often, I would be thrilled if I ended up with six or seven slides worth saving, maybe one to two of which were worth turning into 8 × 10 prints. With modern DSLRs, you can “preview” the shot on the back of the camera and reshoot if needed. The preview screen may not be totally accurate when it comes to color, but I can easily tell if I have committed some of the cardinal sins of photography, including bad framing, over-exposure, or blurry focus. With auto-bracketing, you can take quite a number of images all at once. All of this is just costing you storage space, which is quite cheap and plentiful. So, I suggest that you shoot as often as you can, even if it’s not your design. Shoot for friends or volunteer for other local theatres. Once you have the equipment, it is now essentially free to practice, so there is no reason not to get out there as often as you can. This will allow you to become very familiar with your camera and all its settings. It will allow you to anticipate what settings you might want for an upcoming shot, giving you a chance to change those settings without holding up the photo-call. You should become so familiar with your camera’s major settings (the ones mainly accessed by dials and buttons, not buried in software menus) that you can make changes on the fly, in the dark, without having to look at the settings. While still in school, I often shot photo-calls for friends as long as they covered my film/processing costs, and I let them have unrestricted rights to use the results for their portfolios, as long as I could use the photos in my photography portfolio as well. On many occasions, I shot for more than one area, requiring me to work with two different cameras. This also involved a lot of running up and down the aisles. A fast, high-quality zoom lens might have done me some good there, but at the time the costs associated with that kind of glass were just too high. Regardless, the practice has paid off in spades, and now that the costs to do so are measured only in time and storage, there is far less of a barrier to you than there was for me. Even if you are working with borrowed equipment, you are training your eye and brain to pay closer attention to framing and composition. The relationship between all the variables that govern exposure are the same from camera to camera; you just need to learn which buttons and dials do what you need. Lastly, the more you shoot, the more confident you will become in your anticipated results, and the easier it will be for you to plan out what you need to do to get the best shots possible.

When it comes to backing up, you need to become a bit obsessive. Back up your shots immediately. Even if you don’t have time to label and sort them all, at least ensure that you have a secure and reliable backup of the files right away. I recommend a two-tier system. You should have a reliable, stable, hardware backup, and a reputable cloud backup. In the slide age, I kept my slides in a safety deposit box, so they were safe from anything, but as I shot more and more, I ran out of space in the box, so I bought a fire-proof file cabinet. This won’t protect against every possible situation, but it was a good start. At least there was a chance they would survive if the apartment building I was in went up in flames. Not happy to think about, but I know more than one person who has lost their portfolio or photographs to a house fire. Now that we are in a digital age, it’s easy and free to make copies of the file – in fact the photos in this book are all digital copies of the original files.

By having a physical copy and a virtual copy, you are protecting yourself from local disasters, such as fire, flood, tornado, or theft. If any of those things happen, you still have the virtual copy, which should remain on the servers of your backup company of choice for years to come. Depending on your situation, the physical or virtual copy might be easier to access, but you now know that they are identical files, so it shouldn’t matter which one you use. Many people choose to use services like Dropbox, Carbonite, iCloud, Mozy, or Symantec, to name a few. I have Dropbox set up on mine to automatically back up any photo device I connect to my laptop, without having to think about it. Even my phone is set up to do this, and it will back up automatically over Wi-Fi without having to remember to connect it. This is an exceedingly useful feature if you end up using your phone to capture in-process images of your work. Choose one with excellent reviews and a solid reputation. Hopefully the cost will be within your reach, but keep in mind that if you lose these files, you can’t ever recreate them, so consider this part of your job security. The same goes for the physical media that you use for your hard backup. If you are solely relying on the tired, old hard drive in your laptop, then you are really running the risk of losing everything. Laptops can get stolen; hard drives can crash and eat all the data. Use a high-quality external storage device that can be unplugged and locked up somewhere safe. This keeps the data physically secure, but also separates the data from your computer, so that it can’t get corrupted by a virus or locked down with ransom-ware. You might be able to use a USB key to start with, as they are available in high-capacity models that are quite reasonable now. If you shoot a lot, however, you will eventually need to move to some sort of external hard drive that can be plugged into your computer, or perhaps a network-attached storage device (NAS) plugged into your router. Seagate, Crucial, and SanDisk have proven to be pretty reliable, but check the reviews to see if this changes from model to model. If you have a Mac, you can take advantage of its built-in Time Machine for local backups to an external hard drive, or better yet, link to a Time Capsule and have your router and NAS bundled together in one device.

No matter which way you go, be sure to go home and download your photos right away. Here are a few things that have tripped me up in the past:

- If you are downloading directly from the camera to the laptop, make sure your batteries are recharged, or plug your camera into a wall outlet to keep it on. I’ve had my battery die in the middle of a download that ended up taking far longer than I thought, which caused the memory card to get corrupted, since it turned off in the middle of the download and wasn’t “ejected” properly from the computer.

- Download right away, and at least put them all in a labeled folder with show and date. One time, I didn’t do this, and it bit me. I needed a shot immediately for someone doing publicity on the show, so I just downloaded the one shot I needed, and figured I’d go back and take care of the rest later. I forgot that I hadn’t ever downloaded the rest of the shots, and the next time I used the camera I reformatted the card at the start of the call. As I hit the “OK” button, I suddenly realized what I’d done, but it was too late. So, all I have from that entire show is one shot, which is a shame.

- Once your photos are all copied over to your laptop, eject the chip from your computer or otherwise properly disconnect your camera. Once it is disconnected, double check that all the photos are present in the new folder you created. One time I got ahead of myself and thought that the computer was done, popped out the chip, and didn’t check on this. It turned out that half of the photos were still uploading, and I almost lost them. Luckily, I was able to go back and re-download the missing files.

Even if you have taken care to do this right away, sometimes things happen and a file gets corrupted. I have no idea what happened to this particular shot, which I found had been damaged at some point when I was sorting through everything to label them. Luckily, the RAW version of the file was still intact, and I had other bracketed versions of the exposure, so I was covered.

Figure 19.1: Corrupted file. This was the JPEG version of the shot.

Preferably you should sort, label, and evaluate your shots right away, but if you have to wait, don’t wait too long. One of the great things about digital photography is the ease with which you can generate 200 or 300 photo files in a night. If you are generating both JPEG and RAW image files, with a five-shot bracket, that’s 10 files per button press. Since it’s so quick to do this, I will even take multiple bracket sets of one stage look, perhaps to cover myself with slightly different framing or composition. Or perhaps I saw an actor move a bit, and I gave them a pause and had them hold again, and then I reshot. Through all this, I could end up with 10 times as many files to look through compared to that single, 36-exposure roll of film I used to be limited by. This is all great news, but it means that you have a lot more to go through. When I got my box of slides back from the developer, I used to sit at my light table, sort through all of them, and discard the ones that were too over-exposed to be of any use. The under-exposed ones might be able to be used for a print, but the ones that were blown out were pointless to keep. You need to decide for yourself if it’s worth keeping the files that are similarly over-exposed. You don’t have to worry about storing and moving boxes and boxes of physical slides any more, but you do have to deal with storing them somewhere digitally. I haven’t thrown out the files I don’t see using yet, mainly due to time. I pick through and identify the ones I want to use in my portfolio, and mark them specially or keep them in a special “Use These!” subfolder. I don’t want to have to wade through several hundred images again the next time I need a shot from my library of images.

Depending on your computer’s operating system, your file system may not be able to preview the RAW versions of your files. If you are taking pairs of shots, then the file system will display them adjacent to each other, since they will be numbered the same with a different file extension.

In this case, the file in the screenshot is named DSC_0038.JPG, and the RAW version is right after it in the list, and labeled DSC_0038.NEF. The current MacBook OS is able to support the display of thumbnail images of both JPEG and RAW files versions, so it’s easy to look at anything in the file folder. If you can’t see a thumbnail of the RAW version, then having the JPEG version adjacent to it lets you quickly and easily cull through to decide which ones you might want to open up in Photoshop for a closer look, and which ones you can discard or archive. There are many ways to sort, especially on a Mac, including the thumbnails page or the cover-flow page. Use whatever method makes the work go quickly and efficiently for you, and that will help you stay on top of cataloging everything. Once you’ve identified what you plan to keep, you can rename all the files, or just the ones that are important if you like. I tend to leave them with their original numbering, just as they came out of the camera, but use carefully labeled folders to eliminate confusion.

Figure 19.2: Sorting photo files on a MacBook Pro.

I wrote in Chapter 16 about the rules and laws that may govern a photo-call. Generally speaking, if you are using the shots for your portfolio, and are not selling them, then you should be fine with taking them for “archival” purposes. If, however, you are planning on using them in a commercial situation, then you will likely need to obtain a waiver or release. I have found the stage management team to be very helpful in this respect. I give them enough copies for the entire cast several days in advance, and they are usually able to catch all the performers when they arrive for the rehearsal or show call the next day. Don’t wait until after the call; it’s too late to deal with any issues that might arise from the request at that point, and you might have a tough time tracking everyone down.

Several of the examples I’ve used, however, date back several decades, and whereas I’ve made a good-faith effort to locate and contact the individuals in the photographs, often I’ve run out of luck. Your legal situation, and projected use, may or may not require this, but you should make every effort to respect the right of all the artists involved. Generally, everyone I’ve worked with has been very cooperative and participatory, and usually the performers are happy if they can get a copy of their own of some of the shots.

Figure 19.3: This is an example of what a release might look like. This is what I used to obtain permissions for the photos in this book.

Only one time in my career have I ever had a run-in with another photographer. I was working on a show, and my travel schedule just didn’t allow for a photo-call to happen outside of the technical rehearsals I was available for. I thought maybe I would step aside during a few cues and take a few shots from the tech table so that I at least had a bit of a record of the show, even if it wasn’t what I had hoped to get. A commercial photographer, hired by the venue, was also there shooting the final dress, and came by to angrily inform me that only he had rights to take pictures during the show, and that I wasn’t allowed to take any pictures. I pointed out that the producers were aware that I was taking pictures, I was only taking archival shots for my portfolio, and that I hadn’t been able to arrange a separate photo-call to satisfy those needs. The other photographer stood his ground, stating that I was interfering with his rights to be the sole person documenting the show for the company. I tried to be as polite as possible, but didn’t have time to debate this issue with a dress rehearsal going on. I pointed out to him that as one of the visual artists involved in the creation of the stage looks he was capturing, he was in turn violating my rights as an artist by not asking my permission to document the lighting design work I had created. Suddenly he realized the extent of the situation, and we parted friends with the verbal agreement that he could take all the pictures he wanted of my lighting design, as long as he shared a copy of the shots he took so that I could use them in my portfolio. Everyone walked away happy, and I got more shots of the show than I would have otherwise. Be clear about your intended uses, and polite when you ask for permissions, and everything should work out fine.

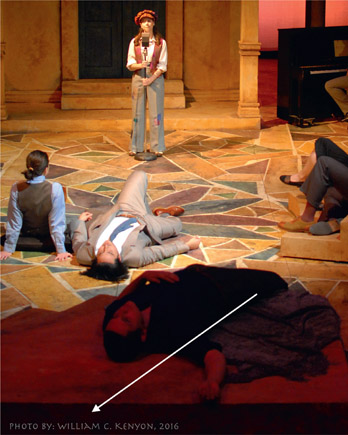

When you use another photographer’s work in your portfolio, you need to cite their work. When you get permission from the photographer to use the work, ask how they would prefer to be cited. Usually a discrete label on or near the photograph is sufficient. I usually ask my students to cite my work this way:

Photo by William C. Kenyon.

If you are using several photos from the same photographer on the same set of portfolio or web pages, you could instead say:

All photographs by William C. Kenyon.

What’s important is that the credit is clearly connected visually to the photo. A semi-transparent watermark is a great way to go, and is something fairly easy to do in Photoshop.

I just added a layer to the image, added a text box, and set the text box to a layer opacity of 50 percent. You can then copy this layer and add it to other files as needed.

Purchasing and maintaining your camera and lens collection can be a stressful and time-consuming task, not to mention the potentially significant costs involved with photography. Cameras are available at many different levels of quality, ability, and feature-sets. What you can afford as a student or freelance professional may limit the options available to you. I chose to invest a larger amount of my available income in cameras than most, partly because it is something that I really enjoy, in addition to something that I needed to get very good at in order to promote my abilities as a designer. You will have to make the decision for yourself as to how much money you put toward this endeavor, but I truly hope that what you have learned from this book will go a long way toward helping you get the best gear you can afford, and squeezing the most value out of that gear.

Figure 19.4: Note the watermarked photo credit in the lower left corner. Twelfth Night, Penn State University, Nov. 2016.

Figure 19.5:

Close-up of Photoshop – adding layer with text for photo credit.

There are three broad categories of camera and estimates of costs:

- Consumer Grade (under $1,000)

- Prosumer Grade (from $1,000 to $2,500)

- Professional Grade (over $2,500)

Many, but not all of the Consumer Grade cameras will be good for this type of photography – you will have to look very closely at all the options available, and determine which ones you can live without if they aren’t all there. Don’t forget to look at how easy it is to change settings…are they easy-access buttons and dials, or are they buried in a multi-layer software menu? Be wary of cameras that are all auto-everything. This is especially true for cameras that only do auto white balance. You will recall from Chapter 8 how important it is to be able to have some control over this setting, and how the “auto” part may not function as needed. Most of the Prosumer Grade cameras are going to do everything you need, and do it quite nicely, but they are a commitment. If you can afford a Professional Grade camera, or otherwise know where to borrow one, that’s great, but I imagine this is probably out of the reach of most theatre practitioners.

All I can say is do your research, ask around, borrow or rent if you want to try before you buy, and you should come out just fine. There are some great resources in the back of this book that should help you in your search. Once you have decided on a platform (brand and camera sensor size), then you can delve into the world of lenses. I bought my Nikon D200 camera body as a “kit,” which paired it with an extra battery, some accessories, and a Sigma-brand lens with a Nikon mount. The kit with the Sigma lens was less expensive than buying the equivalent Nikon lens by a good bit, but I was ultimately very disappointed in the lens, which broke after about two years of fairly easy use. If going this route gets you into a better camera, then great, but just be sure to plan for replacing the lens with something more suited to your needs in the nearer future. These inexpensive “kit” lenses tend to be slow lenses with a medium-zoom range, so they are okay for most things, but not great at anything. As I mentioned before, I stayed in the Nikon family in order to be able to continue to use my older Nikon lenses, although they don’t have the same level of options, especially autofocus, that the newer ones do. I have started to collect a few newer lenses built for the DSLR market, but like the ability to still employ some of my favorite glass from the earlier generations.

Once you start to invest in some good gear, it is important to take good care of it. Here are a few things you can do to prolong your gear’s useful life:

- Don’t leave batteries in the camera during long-term storage. Especially alkaline and “button” or “coin” batteries…they can rupture and leak over time, ruining your camera. If you plan to put the camera on the shelf for a few months, pop the batteries out, put them in a Ziploc bag, and secure the bag to the camera with a rubber band or just keep it nearby.

- Your camera should come with a “body” cap that covers the mirror if you have the lens off. Most theatres are really dusty environments, so even if you are just taking the lens off for a few minutes, the body cap is essential.

- Lenses come with caps for both ends, and any time you have the lens off the camera, you should cap the body end of the lens. Don’t just put it in the box or bag it came with, as it can also get dusty, and then you will transfer that dust right into the body of the camera if you aren’t careful. Of course, always use the front lens cap whenever you aren’t using the camera.

- You should also protect your awesome new favorite lens with an inexpensive ultraviolet (UV) filter. Since we don’t tend to need to use filters for anything else in our world, you can obtain a plain UV filter, which is essentially clear glass with a UV coating, and put it on your lens. It won’t affect your shots at all, and is an excellent bit of extra insurance to help keep your nice lens from getting dirty or scratched and broken. If the filter takes a hit, replace it for less than $20, which is cheap insurance compared to repairing or replacing a good lens.

Figure 19.6: Nikon camera lens with UV filter and lens cap. Note that the UV filter has no effect on the color or sharpness of the fabric it sits on.

- Hot weather is very bad for quality electronics, as I’m sure you know. Be very careful to never leave your camera in a hot car, where the temperatures can rise to well over 130° on a hot day. Even if it’s only 70° outside, interior car temperatures can easily hit the 100° mark. This can have a permanent and damaging effect on the life of the battery, the small motors in the camera and lens, and the image-sensing chip. Your owner’s manual will most likely give you more specific details about your particular camera and what temperature extremes it can handle.

- Extreme cold weather can be equally bad, especially if you don’t let your camera warm slowly back up to room temperature. Parts can become brittle in extreme cold, and glass can crack. Rubber seals can fail, and your battery may prematurely drain. The other major concern is condensation. If you bring a cold camera into a warmer and more humid environment, it will exhibit the same tendency for condensation that you see when you take a can of soda out of the refrigerator. If I’m in a situation where I know this is possible, I try to keep my camera zipped up in its bag for a while so that it can warm up slowly, and the bag helps to keep the moisture in check.

- Most manuals suggest that you avoid pointing your camera directly into the sun. While this is useful advice, you might be thinking this doesn’t matter, since we are indoors for what we do. This is true, but you should also avoid looking directly into the beam of any arc lights that might be in the rig. Some of the higher-wattage moving lights out there are quite powerful, and can potentially damage your image sensor, not to mention hurt your eyes if you look directly at them.

- There are many camera bags out there, but you should try to invest in one that has some thick foam padding protecting the contents. Make sure the bottom and exterior sides are good and solid, and that you have some thick, padded interior dividers. Many bags are lined with Velcro so that you can move the dividers around to customize the bag to your preference. You may even end up with several sizes, for different travel situations.

- I talked a good bit about tripods in Chapter 6, but I just want to revisit this briefly. Quality tripods feel solid; cheap ones feel flimsy. This isn’t the be-all, end-all of advice I can offer, but it certainly is a reasonable start. You might also want to look for adjustable feet. Many tripods have a spike at the end of the leg that can be used in softer surfaces, but the good ones also have a rubber foot that covers over the spike, which is better for smooth surfaces like tile.

- If your camera takes regular batteries, like AAs or AAAs, check and see if you can use the newer rechargeable ones, or the super-long-life lithium batteries. Your owner’s manual will tell you what is permissible for your particular camera. If you can use the lithium batteries, that can be a real bonus at photo-call for two reasons: weight and lifespan. They are so much lighter weight that it makes a noticeable difference in the weight of the camera over the course of an hour. They also last far longer, which is great if you are using the camera constantly over the course of the hour. Just be aware that most of the newer battery types run at full charge until they drop off completely, as opposed to the older alkaline batteries that fade over time, giving you a heads-up that they are nearing the end of their charge. No matter what, ensure that you have spares in your bag, already cut out of the blister packaging, so they are ready to toss in and get you back to shooting.

- If your camera takes a rechargeable battery pack, be sure you have a spare, and be obsessive about making sure yours is charged. The main battery in my Nikon is now about 10 years old, but it still holds a full charge when I charge it. It loses that charge when you store it over time, though, and now over less time than when new. I always plug it in to recharge in the morning of the day of a shoot, and it has proven to be very reliable and has the ability to last a full and busy shoot. I do keep the charger with me in the bag, though, in case I need to toss one on the charger while I use a backup. If you can plug your camera into a wall outlet, it would be good to have that cable with you, and know where an extension cable is so that you can run power into the seats. This is certainly a clunky solution, but might be the only thing that keeps you shooting.

- Cleaning supplies are essential, and should include lens-cleaning solution, lens paper, a small can of pressurized air, and a lens brush. The paper and lens solution is essential for getting oils off your lens, such as a finger-print, whereas the air or brush do a great job with dust and lint, and require less scrubbing of delicate coated lenses. If you are using the UV filter I mentioned, and are careful with the body caps, this will significantly limit any cleaning you have to do to the surface of the filter, which again is a more “disposable” item if it gets damaged or can’t be cleaned. Microfiber cleaning cloths are also very popular and useful now, but must also be cleaned every so often if used a lot. Keep your cleaning cloth stored in a pouch or Ziploc, so it doesn’t pick up grit from the inside of your bag or pack, which can then transfer to the lens and possibly scratch it. Avoid the temptation to use your shirt sleeve or other clothing article to wipe down a lens…some fabrics, especially organic ones, can be more abrasive to a coated lens than you might realize. Additionally, you might also have dirt on your sleeve that gets transferred over to the lens surface. Specialized soft lens brushes are great for getting at dust or lint, especially if it’s stuck on for some reason. You might even find one that has a little pad on it that you can wet down with lens-cleaning solution. Check your owner’s manual for additional information about your particular camera and lens.

- The canned air I mentioned is great, but comes with some cautions. If you are blowing lint off a lens, that’s one thing, but if you have gotten dust on the internal mirror or image sensor, that can be another issue entirely. Canned air, especially at close range, can damage some of the tiny springs in the mirror/shutter curtain mechanism. The air is blowing the dust around, and could make things worse instead of better. Finally, if you’ve used canned air often, you may have had an experience where you get some propellant that shoots out as well, either due to major temperature differences between the can and the surrounding air, or due to a depleted amount of air left in the can. Lastly, if you accidently turn the can sideways, you might also get some propellant instead of air. This material is very cold, and can permanently stain or damage your image sensor. A safer alternate is a blower brush, which has a little rubber squeeze bulb that gives you a puff of air, and you can control the pressure. This is often the preferred method if you have to clean the image sensor. Avoid wiping the sensor with anything, as it is extremely delicate.

- Some cameras are equipped with a self-cleaning image sensor, which can “shake” the dust off. This only moves the dust off the sensor to a “trap” in the camera, which eventually needs to be cleaned professionally. Nonetheless, this can be a very useful solution if you have the option available to you. In the end, you may need to have your camera professionally cleaned at some point. Overall, if you are careful to begin with, all the cleaning issues should be pretty minor. I’ve never had to deal with anything more than a little bit of dust and occasional fingerprint on the UV filter.

- Make sure you have an extra memory card handy, formatted, empty, and ready to go in case your card dies on you or gets full. Cards are cheap now, so it’s easy to pick up an extra one after the pain of buying the initial camera rig has passed.

In addition to buying gear new, there is a vibrant market for used camera gear out there. Depending on where you live, you might even still have access to a camera shop, but these are getting rare. If you are in a large city, though, check around and you might find some resellers that offer used equipment. You really need to be careful though, with any used equipment, since there are things that are obvious, such as dents and dings on the outside of a lens or camera body, but it’s very hard to determine the state of the internals. This is much like buying a used car, so go somewhere with a good reputation, make sure there is a return policy or warranty, and as soon as you buy it, go put the gear through its paces and make sure it performs as expected.

Deals may be found locally on Craigslist.org or other local social-media sites, and of course there are many deals on eBay and other auction sites. Local auctions are also often good places for finding deals on used gear. Again, go into this with your eyes wide open. You might get a real steal, but you need to know what you are looking for, and be sure that whatever you are buying is compatible with your other equipment (if that is a concern). Especially with online sellers, do your homework, especially with companies that are “click-thru” sellers on otherwise reputable sites like Amazon.

Visit my website for discussions and questions and I invite you to share your work there as well. As the world of digital photography is changing at an ever-increasing rate, there is no way for me to predict what equipment will be out by the time this book is published. This is a topic that I have found many people to be passionate about, and I look forward to hosting a vigorous conversation on the art of theatre photography there.

Best of luck, and I truly hope that this book has helped you to be successful with your photographic endeavors.