The tourism product

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

divide tourist attractions into four major types and their attendant subtypes

appreciate the diversity of these attractions

discuss the management implications that pertain to each attraction type and subtype

identify the various attraction attributes that can be assessed in order to make informed management and planning decisions

explain the basic characteristics of the tourism industry’s main sectors

assess the major contemporary trends affecting these sectors

describe the growing diversification and specialisation of products provided by the tourism industry

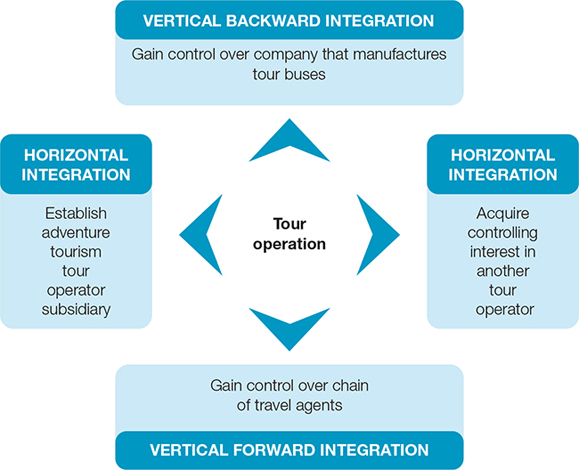

discuss the implications of the concepts of integration and globalisation as they apply to the tourism industry.

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

The previous chapter outlined the ‘pull’ factors that stimulate the development of particular places as tourist destinations, and described the tourism status of the world’s major regions in the context of these forces. Chapter 5 continues to examine the supply side of the tourism system by focusing on the tourism product, which can be defined as the combination of tourist attractions and the tourism industry. While commercial attractions such as theme parks and casinos are elements of the tourist industry, others, such as generic noncommercial scenery, local people and climate, are not. For this reason, and because they are an essential and diverse component of tourism systems, attractions are examined separately from the industry in the following section. We then follow with a discussion of the other major components of the tourism industry, including travel agencies, transportation, accommodation, tour operators and merchandise. The chapter concludes by considering structural changes within the contemporary tourism industry.

TOURIST ATTRACTIONS

TOURIST ATTRACTIONS

The availability of tourist attractions is an essential ‘pull’ factor (see chapter 4), and destinations should therefore benefit from having a diversity of such resources. The compilation of an attraction inventory incorporating actual and potential sites and events, is a fundamental step towards ensuring that a destination realises its full tourism potential in this regard. There is at present no classification system of attractions that is universally followed among tourism stakeholders. However, a distinction between mainly ‘natural’ and mainly ‘cultural’ phenomena is commonly made. The classification scheme proposed in figure 5.1 adheres to the natural/cultural distinction for discussion purposes, and makes a further distinction between sites and events. Four basic categories of attraction are thereby generated: natural sites, natural events, cultural sites and cultural events. The use of dotted lines in figure 5.1 to separate these categories recognises that distinctions between ‘natural’ and ‘cultural’, and between ‘site’ and ‘event’, are not always clear. The use of these categories in the following subsections therefore should not obscure the fact that many if not most attractions are category hybrids. A national park, for example, may combine topographical, cultural, floral and faunal elements of the site. Moreover, although it is a site, it may also provide a venue for various cultural and natural events.

The following material is not an exhaustive treatment of this immense and complex topic, but rather it is meant to illustrate the diversity of attractions as well as management issues associated with various types and subtypes. One underlying theme is the likelihood that most places are not adequately utilising their potential range of attractions. A related theme is the role of imagination and creativity in transforming apparent destination liabilities into tourism resources, reflecting the subjective nature of the latter concept.

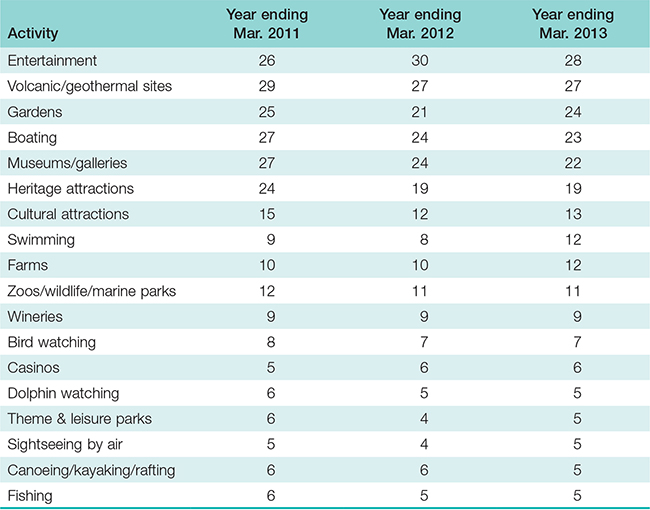

Natural sites

Natural attractions, as the name implies, are associated more closely with the natural environment rather than the cultural environment. Natural site attractions can be subdivided into topography, climate, hydrology, wildlife, and vegetation. Inbound tourists are strongly influenced to visit Australia and New Zealand by natural sites such as the ocean, botanical gardens, zoos and national parks. In the case of New Zealand, ‘walking/trekking’ (also known as ‘tramping’) — the third most popular reported specific type of attraction or activity amongst inbound tourists — is largely 119pursued in natural settings, as are land sightseeing and lookouts or viewing platforms, the fourth and fifth most popular activities, respectively (see table 5.1). Destinations have little scope for changing their natural assets — for example, they either possess high mountains, or they do not. A challenge, therefore, is to manipulate market image so that relatively ‘unattractive’ natural phenomena such as grasslands can be converted into lucrative tourism resources.

FIGURE 5.1 Generic inventory of tourist attractions

TABLE 5.1 Top twenty activities by inbound tourists to New Zealand 2011–13, by percentage reporting participation in activity

Source: New Zealand Ministry of Business, Innovation & Employment 2012

120

Topography

Topography refers to geological features in the physical landscape such as mountains, valleys, plateaus, islands, canyons, deltas, dunes, cliffs, beaches, volcanoes and caves. Gemstones and fossils are a special type of topographical feature, locally important in Australian locations such as Coober Pedy in South Australia (opals), O’Briens Creek in Queensland (topaz) and the New England region of New South Wales. The potential for dinosaur fossils to foster a tourism industry in remote parts of Queensland has also been considered (Laws & Scott 2003).

Mountains

Mountains illustrate the subjective and changing nature of tourism resources. Long feared and despised as hazardous wastelands harbouring bandits and dangerous animals, the image of alpine environments was rehabilitated during the European Romanticist period of the early 1800s, and in a more induced way by the efforts of trans-continental railway companies in North America to increase revenue through the construction and promotion of luxury alpine resorts (Hart 1983). As a result, scenically dramatic alpine regions such as the European Alps and the North American Rockies emerged as highly desirable venues for tourist activity, and have been gradually incorporated into the global pleasure periphery. With regard to markets, Beedie and Hudson (2003) describe how remoteness fostered an elitist ‘mountaineer’ form of tourism until the latter half of the twentieth century, when improved access (a pull factor) and increased discretionary time and money (push factors) led to the ‘democratisation’ of alpine landscapes through skiing and mass adventure tourism. Some remote areas, however, continue to fulfil the complex motivations of elite adventure tourists 121(see Breakthrough tourism: Adventure tourism and rush). Lower and less dramatic mountain ranges, such as the American Appalachian Mountains, the Russian Urals and the coastal ranges of Australia, are also highly valued for tourism purposes although arguably they did not undergo the elite-to-mass transition to the same extent. Previously inaccessible ranges, such as the Himalayas of Asia, the South American Andes, the Southern Alps of New Zealand and the Atlas Mountains of Africa, are now also being incorporated into the pleasure periphery.

Certain individual mountains, by merit of exceptional height, aesthetics or religious significance, possess a symbolic value as an iconic attraction that tourists readily associate with particular destinations. Uluru (formerly Ayers Rock) is the best Australian example, while other well-known examples include Mt Everest (Sagarmatha), the Matterhorn, Kilimanjaro (Tanzania) and Japan’s Mt Fuji, which is notable as an almost perfect composite volcano.

breakthrough tourism

![]() ADVENTURE TOURISM AND RUSH

ADVENTURE TOURISM AND RUSH

Travel motivation is a more complex construct than travel purpose, as demonstrated by the adventure travel industry. Various studies identify thrill, overcoming fear, exercising and developing specialised skills, achieving difficult goals, staying fit, and facing danger as commonly expressed motivations for participating in adventure experiences. However, Buckley (2012) describes a ‘risk recreation paradox’ where for most participants operators provide only the semblance of risk to avoid client injury, litigation costs and negative publicity. Among skilled participants in particular, Buckley identifies ‘rush’ as a more prevalent motivation. Many who experience rush claim that it cannot be fully appreciated or accurately described by those who do not experience it, although Buckley drew upon his own emic (insider) experiences as a skilled adventure tourist to formalise the concept. He regards it essentially as something that may emerge during the successful performance of an adventure activity at the limits of one’s individual capacities. Analytically, it is a rare, unified, intense and emotional peak experience that entails both thrill — an adrenalin-filled physiological response — and flow — being intensely absorbed both mentally and physically in the activity. Rush is both addictive and relative; that is, it can be experienced by a veteran or a novice (e.g. a first successful surfing experience), and in either case stimulates a stronger desire for a repeat sensation, usually at a higher level of engagement. Risk and danger, according to Buckley, are unavoidable aspects of rush, but are not motivations in their own right. At the very highest levels, places that have the potential to provide peak sensations of rush, such as remote high mountains or offshore waters which generate exceptionally high waves, define a very special and elite geography of iconic destinations. However, rush is potentially accessible to less experienced participants in a greater variety of settings, and is in fact a definable concept that is invaluable for better understanding human behaviour in general and the environments that foster different behaviours.

122

Beaches

As with mountains, beaches were not always perceived positively as tourist attractions. Their popularity is associated with the Industrial Revolution and particularly with the emergence of the pleasure periphery after World War II (see chapters 3 and 4). Currently, beaches are perhaps the most stereotypical symbol of mass tourism and the pleasure periphery. Not all types of beaches, however, are equally favoured by tourists. Dark-hued beaches derived from the erosion of volcanic rock are not as popular as the fine white sandy beaches created from limestone or coral, as the former generate very hot sand and the illusion of murky water while the latter produce the turquoise water effect highly valued by tourists and destination marketers. This in large part accounts for the higher level of 3S resort development in ‘coral’ Caribbean destinations such as Antigua and the Bahamas, than in ‘volcanic’ islands such as Dominica and St Vincent. Nevertheless, many beach settings that by Australian standards would be considered far too cold and aesthetically unappealing have given rise to major coastal resort cities such as Blackpool (United Kingdom) that appeal primarily to nearby domestic markets (see chapter 3).

Climate

Before the era of modern mass tourism, a change in climate was a major motivation for travel. There was a search for cooler and drier weather relative to the uncomfortable summer heat and humidity of urban areas. Thus, escape to coastal resorts in the United Kingdom and the United States during the summer was and still is a quest for cooler rather than warmer temperatures. The British and Dutch established highland resorts in their Asian colonies for similar purposes, and many of these are still used for tourism purposes by the postcolonial indigenous elite and middle class. Examples include Simla and Darjeeling in India (Jutla 2000), and the Cameron Highlands of Malaysia. This impulse is also evident among the small but increasing number of Middle Eastern visitors to Australia during the torrid summer of the Arabian Peninsula.

With the emergence of the pleasure periphery, temperature and seasonal patterns were reversed as great numbers of snowbirds travelled to Florida, the Caribbean, the Mediterranean, Hawaii and other warm weather destinations to escape cold winter conditions in their home regions. These migrations are having economic and social effects on an expanding array of emerging economies, as illustrated by the growing seasonal enclaves of retired French caravan owners being formed on the Atlantic coast of Morocco (Viallon 2012). A snowbird-type migration is also apparent on a smaller scale from Australian states such as Victoria and South Australia to the coast of Queensland.

Some areas, however, can be too hot for most tourists, as reflected in the low demand for equatorial and hot desert tourism. Essentially, a subtropical range of approximately 20–30 C is considered optimal for 3S tourism, and this is a good climatic indicator of the potential for large-scale tourism development in a particular beach-based destination, provided that other basic ‘pull’ criteria are also present (Boniface, Cooper & Cooper 2012). The one major exception to the cool-to-hot trend is the growing popularity of winter sports such as downhill skiing, snowboarding and snowmobiling, which involve a cool-to-cool migration or, less frequently, a warm-to-cool migration. Whatever the specific dynamic, cyclic changes in weather within both the origin and destination regions lead to significant seasonal fluctuations in tourist flows, presenting tourism managers with additional management challenges (see chapter 8).123

Water

Water is a significant tourism resource only under certain conditions. For swimming, prerequisites include good water quality, a comfortable water temperature and calm and safe water conditions. Calm turquoise waters combine with warm temperatures and white-sand beaches to complete the stereotype of an idyllic 3S resort setting (figure 5.2). For surfing, however, calm waters are a liability — which accounts for the emergence of only certain parts of the Australian coast, Hawaii and California as ‘hotspots’ for surfing aficionados (Barbieri & Sotomayor 2013). Oceans and seas, where they interface subtropical beaches, are probably the most desirable and lucrative venue for nature-based tourism development. Freshwater lakes are also significant for outdoor recreational activities such as boating, and for the establishment of second homes and cottages. Extensive recreational hinterlands, dominated by lake-based cottage or second home developments, are common in parts of Europe and North America. The Muskoka region of Canada is an excellent example, its development having been facilitated by the presence of several thousand highly indented glacial lakes (i.e. the destination region), its proximity to Toronto (i.e. the origin region) and the existence of connecting railways and roads (i.e. the transit region) (Svenson 2004).

FIGURE 5.2 An idyllic beachscape of the Caribbean pleasure periphery

Rivers and waterfalls

Waterfalls in particular hold a strong inherent aesthetic appeal for many people, and often constitute a core iconic attraction around which secondary attractions, and sometimes entire resort communities, are established. Niagara Falls (on the United States–Canada border) is a prime example of a waterfall-based tourism agglomeration. Other examples include Victoria Falls (on the Zimbabwe–Zambia border) and Iguaçú Falls (on the Brazil–Paraguay border). Much smaller waterfalls are an integral part of the tourism product in the hinterland of Australia’s Gold Coast (Hudson 2004).

An important management dimension of freshwater-based tourism is competing demand from politically and economically powerful sectors such as agriculture (irrigation), manufacturing (as a water source and an outlet for effluents) and transportation (bulk transport). Such competition, which implicates the importance of water as an attraction in itself as well as a facilitator of other attractions such as golf courses, is likely to accelerate as freshwater resources are further degraded and depleted by the combined effects of mismanagement and climate change (Becken & Hay 2012). As with skiing, such issues are especially acute in Australia, where major waterways such as the Murray and Darling rivers are modest affairs by European or Asian standards, with precarious water supplies subject to intense competition for access.

Geothermal waters

As discussed in chapter 3, spas were an historically important form of tourism that receded in significance during the ascendancy of seaside tourism. Contemporary demographic and social trends, however, favour a resurgence in this type of resort (see chapter 10). Germany may be indicative, where an ageing but health-conscious 124population supports over 300 officially-recognised spas which collectively account for about one-third of all visitor-nights and over 350 000 jobs. Combining geothermal waters with health food, meditation and other ‘wellness’ products is a growing trend in the European spa industry (Pforr & Locher 2012).

Wildlife

As a tourism resource, wildlife can be classified in several ways for managerial purposes. First, a distinction can be made between captive and noncaptive wildlife. The clearest example of the former is a zoo, which is a hybrid natural/cultural attraction. At the opposite end of the continuum are wilderness areas where the movement of animals is unrestricted. Trade-offs are implicit in the tourist experience associated with each scenario. For example, a visitor is virtually guaranteed of seeing the animal in a zoo, but there is minimal habitat context, no thrill of discovery and no risk. In a wilderness or semi-wilderness situation, the opposite holds true. Many zoos are now being reconstructed and reinvented as ‘wildlife parks’ or ‘zoological parks’ that provide a viewing experience within a quasi-natural and more humane environment, thereby compromising between these two extremes. Tiger-related tourism demonstrates the trade-offs and ambiguities that occur between the captive and non-captive options. In India, noncaptive semi-wilderness settings provide a favourable natural environment for tigers but foster an unsustainable form of tourism due to relentless tourist harassment of these animals. In contrast, zoos are a less-than-ideal ecological setting but provide captive breeding and educational opportunities that may ultimately save the species from extinction as native wildlife habitats disappear (Cohen 2012).

Consumptive and nonconsumptive dimensions

Wildlife is also commonly classified along a consumptive/nonconsumptive spectrum. The former usually refers to hunting and fishing, which are long established as a mainly domestic form of tourism in North America, Australia, New Zealand and Europe (Lovelock 2008). Related activities that have more of an international dimension include big-game hunting (important in parts of Africa and North America) and deep-sea fishing, which is significant in many coastal destinations of Australia (Bauer & Herr 2004). Because of the consumptive nature of these activities, managers must always be alert to their effect on wildlife population levels. In Australia, hunting is valued as a management tool for keeping exotic pest species such as feral pigs in balance with environmental carrying capacities (Craig-Smith & Dryden 2008).

In many areas ‘nonconsumptive’ wildlife-based pursuits such as ecotourism are overtaking hunting and fishing in importance (see chapter 11). This is creating a dilemma for some hunting-oriented businesses and destinations, which must decide whether to remain focused on hunting, switch to ecotourism or attempt to accommodate both of these potentially incompatible activities. Such conflicts are evident in eastern North American settings where white-tailed deer are valued for very different reasons by recreational hunters and ecotourists (Che 2011). One criticism of the ‘consumptive/nonconsumptive’ mode of classification is that both dimensions are inherent in all forms of wildlife-based tourism. The ‘nonconsumptive’ experience of being outdoors for its own sake, for example, is usually an intrinsic part of hunting and fishing, while ecotourists consume many different products (e.g. petrol, food, souvenirs) as part of the wildlife-viewing experience. Maintaining an inventory of observed wildlife, as many avid birdwatchers do, can also be regarded as a symbolic form of ‘consumption’.125

Vegetation

Vegetation exists interdependently with wildlife and, therefore, cannot be divorced from the ecotourism equation. However, there are also situations where trees, flowers or shrubs are a primary rather than a supportive attraction. Examples include the giant redwood trees of northern California and the wildflower meadows of Western Australia. In parts of Australia and elsewhere, a specialised interest in orchids is notable for having conflicting nonconsumptive (e.g. photographic) and consumptive (e.g. collection) dimensions (Ballantyne & Pickering 2012). The captive/noncaptive continuum is only partially useful in classifying flora resources, since vegetation is essentially immobile. For managers this means that inventories are relatively stable, and tourists can be virtually guaranteed of seeing the attraction (although this does not pertain to weather-dependent attractions such as autumn colour and spring flower displays). However, these same qualities may imply a greater vulnerability to damage and overexploitation. The carving of initials into tree trunks and the removal of limbs for firewood are common examples of vegetation abuse associated with tourism and outdoor recreation. The ‘captive’ flora equivalent of a zoo is a botanical garden. These are usually located in larger urban areas, and as a result consistently rank among the top attractions for inbound tourists in countries such as Australia. Accordingly, they function as important centres for public education (Moskwa & Crilley 2012).

Protected natural areas

Protected natural areas such as national parks are an amalgam of topographical, hydrological, zoological, vegetation and cultural resources, and hence constitute a composite attraction. As natural attractions, high-order protected areas stand out for at least four reasons.

Their strictly protected status ensures, at least theoretically, that the integrity and attractiveness of their constituent natural resources is safeguarded.

The amount of land available in a relatively undisturbed state is rapidly declining due to habitat destruction, thereby ensuring the status of high-order protected areas as scarce and desirable tourism resources.

Protection of such areas was originally motivated by the presence of exceptional natural qualities that are attractive to many tourists, such as scenic mountain ranges or rare species of animals and plants.

An area having been designated as a national park or World Heritage Site confers status on that space as an attraction, since most people assume that it must be special to warrant such designation.

For all these reasons, protected natural areas are now among the most popular international and domestic tourism attractions. Some national parks, such as Yellowstone, Grand Canyon and Yosemite (all in the United States), Banff (Canada) and Kakadu, Lamington and Uluru (Australia) are major and even iconic attractions in their respective countries. This is ironic given that many protected areas were originally established for preservation purposes, without any consideration being given to the possibility that they might someday be alluring to large numbers of tourists and other visitors. However, as funding cutbacks and external systems such as agriculture and logging pose an increased threat to these areas, their managers are now more open to tourism as a potentially compatible revenue-generating activity that may serve to pre-empt the intrusion of more destructive activities (Tisdell & Wilson 2012) (see chapter 11).126

Natural events

Natural events are often independent of particular locations and unpredictable in their occurrence and magnitude. Bird migrations are a good illustration. The Canadian province of Saskatchewan is becoming popular for the spring and autumn migrations of massive numbers of waterfowl, but the probability of arriving at the right place at the right time to see the spectacular flocks is dictated by various factors, including local weather conditions and larger-scale climate shifts. Many communities have capitalised on these movements by holding birding festivals during predicted peak activity periods, often using them as occasions to educate attendees about environmental issues facing the target species (Lawton 2009).

Solar eclipses and comets are rarer but more predictable events that attract large numbers of tourists to locations where good viewing conditions are anticipated (Weaver 2011a). Volcanic eruptions (which appeal to many tourists because of their beauty and danger) are generally associated with known locations (thus they are sites as well as events), but are often less certain with respect to occurrence. Lodgings have been established in the vicinity of Costa Rica’s Arenal volcano specifically to accommodate the viewing of its nightly eruptions, while the predictable volcanic activity of Mt Yasur is the primary attraction on the island of Tanna in the Pacific archipelagic state of Vanuatu.

A natural event associated with oceans and seas is tidal action. To become a tourism resource, tidal activity must have a dramatic or superlative component. One area that has taken advantage of its exceptional tidal action is Canada’s Bay of Fundy (between the provinces of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick), where ideal geographical conditions produce tidal fluctuations of 12 to 15 metres, allegedly the highest in the world. Extreme weather conditions can produce natural events, as for example when abundant rainfall replenishes the usually dry Lake Eyre basin in South Australia, creating a brief oceanic effect in the desert. This is a good example of an ephemeral attraction.

Cultural sites

Cultural sites, also known as ‘built’, ‘constructed’ or ‘human-made’ sites, are as or more diverse than their natural counterparts. Categories of convenience include prehistorical, historical, contemporary, economic activity, specialised recreational and retail. As with natural sites, these distinctions are often blurred when considering specific attractions.

Prehistorical

Prehistorical attractions, including rock paintings, rock etchings, middens, mounds and other sites associated with indigenous people, occur in many parts of Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the United States and South Africa (Duval & Smith 2013). Many of these attractions are affiliated with surviving indigenous groups, and issues of control, appropriation, proper interpretation and effective management against excessive visitation therefore all have contemporary relevance (Weaver 2010a). A distinct category of prehistorical sites is the megalithic sites associated with ‘lost’ cultures, which are attractive because of their mysterious origins as well as their impressive appearance. The New Age pilgrimage site of Stonehenge (United Kingdom) is a primary example. Others include the giant carved heads of Easter Island and the Nazca rock carving lines of Peru.127

Historical

Historical sites are distinguished from prehistorical sites by their more definite associations with specific civilisations or eras that fall under the scope of ‘recorded history’. As with ‘heritage’, there is no single or universal criterion that determines when a contemporary artefact becomes ‘historical’. Usually this is a matter of consensus within a local community or among scholars, the assessment of a particular individual, or simply a promotional tactic. Historical sites can be divided into many subcategories, and only a few of the more prominent of these are outlined below.

Monuments and structures

Ancient monuments and structures that have attained prominence as attractions within their respective countries include the pyramids of Egypt, the Colosseum in Rome and the Parthenon in Athens. More recent examples include Angkor Wat (Angkor, Cambodia), the Eiffel Tower (Paris, France), the Statue of Liberty (New York, USA), the Taj Mahal (Agra, India), the Kremlin (Moscow, Russia), Mount Rushmore (South Dakota, USA) and the UK’s Tower of London. Sydney’s Harbour Bridge and Opera House also fall in this category. Beyond these marquee attractions, generic structures that have evolved into attractions include the numerous castles of Europe, the Hindu temples of India and the colonial-era sugar mills of the Caribbean.

Battlefields

Battlefields are among the most popular of all tourist attractions, which demonstrates, ironically, that the long-term impacts of major wars on tourism are often very positive (Butler & Suntikul 2012). Battle sites such as Thermopylae (fought in 480 BC between the Spartans and Persians), Hastings (fought in 1066 between the Anglo-Saxons and Normans) and Waterloo (fought in 1815 between the French and British/Prussians) are still extremely popular centuries after their occurrence. The emergence of more recent battlefields (such as Gallipoli and the American Civil War site at Gettysburg) as even higher profile attractions is due to several factors, including:

the accurate identification and marking of specific sites and events throughout the battlefields, which is possible because of the degree to which modern battles are documented

sophisticated levels of interpretation made available to visitors

attractive park-like settings

the stature of certain battlefields as ‘sacred’ sites or events that changed history (e.g. Gettysburg as the ‘turning point of the American Civil War’ and Gallipoli as a catalyst in the forging of an Australian national identity)

personal connections — many current visitors have great-grandparents or other ancestors who fought in these battles. Indeed, World War Two battles such as D-Day (the day in 1944 when Allied forces landed in France), Stalingrad (the high water mark of Germany’s Russian invasion) and the Kokoda Track campaign in Papua New Guinea are still being attended by surviving veterans.

Other war- or military-related sites that frequently evolve into tourist attractions include military cemeteries, fortresses and barracks (e.g. the Hyde Park Barracks in Sydney), and defensive walls (e.g. the Great Wall of China and Hadrian’s Wall in England). The Great Wall attracts an estimated 10 million mostly domestic tourists per year (Su & Wall 2012). Battlefields and other military sites are an example of a particularly fascinating phenomenon known as dark tourism, which encompasses sites and events that become attractive to some tourists because of their associations with death, conflict or suffering (Dale & Robinson 2011). Other examples include 128assassination sites (e.g. for John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King), locations of mass killings (e.g. Port Arthur (Tasmania), the World Trade Center site, and Holocaust concentration camps) and places associated with the supernatural and occult (e.g. Dracula’s castle in Transylvania, and ‘haunted houses’). Holocaust sites are particularly intriguing because of the extent to which these have been developed as major tourist attractions not just in the Eastern European places where the Holocaust occurred (Podoshen & Hunt 2011), but also as ‘Holocaust museums’ in many cities around the world with no direct association to those events (Cohen 2011).

Heritage districts and landscapes

In many cities, historical districts are preserved and managed as tourism-related areas that combine attractions (e.g. restored historical buildings) and services (e.g. accommodation, restaurants, shops). Preserved walled cities such as Rothenburg (Germany), York (England), the Forbidden City (Beijing) and the Old Town district of Prague (Czech Republic) fall into this category, as does the French Quarter of New Orleans, USA. The Millers Point precinct of downtown Sydney is one of the best Australian examples, with its mixture of maritime-related historical buildings, small hotels, public open space, theatres and residential areas. Rural heritage landscapes are not as well known or as well protected. An Australian example is the German cultural landscape of the Barossa Valley in South Australia. Other rural regions, such as Australia’s Outback and the southern provinces of China, are developing heritage tourism industries that focus on the traditions and lifestyles of indigenous residents who still live there and often constitute the majority population. Such destinations usually generate controversy and raise questions as to the place and status of these people in their respective countries (see Contemporary issue: Experiencing a different China in Yunnan Province).

contemporary issue

![]() EXPERIENCING A DIFFERENT CHINA IN YUNNAN PROVINCE

EXPERIENCING A DIFFERENT CHINA IN YUNNAN PROVINCE

The culture of indigenous people in southern China has become a major attraction for domestic as well as international tourists, and this exposure has had profound implications for the affected ethnic groups. This is illustrated by the World Heritage-listed town of Lijiang in Yunnan Province (Zhu 2012). Dominated by the Naxi people, Lijiang is a tourism ‘hotspot’ that in 2009 attracted 7.6 million visitors to its ethnic performances and heritage sites. Tourists are drawn to ‘traditional’ cultural displays, the ‘authenticity’ of which is seemingly confirmed by the use of old male Naxi musicians in traditional costumes playing ancient-style instruments. A rustic stage setting completes the timeless effect. Such performances, however, are carefully choreographed illusions with substantial Han Chinese influence. Developed deliberately over a long period to meet the expectations of mainly Western audiences, the highly commercialised theatrical performances are strongly supported by government because ethnic minorities who preserve and 129celebrate their ‘own’ culture are seen to be thriving under the embrace of the Socialist Motherland. To this extent, ethnic tourism in Lijiang and elsewhere is a projection of China’s soft power, especially to international audiences. For the Naxi, benefits do derive from an improved material standard of living and from opportunities to preserve some aspects of their traditional culture. However, associated costs include the reinforcement of stereotypes, with some performances emphasising a happy-go-lucky and simple lifestyle dominated by drinking and singing. Also disconcerting has been the influx of Han Chinese migrants to meet the demands of the tourism industry as Lijiang is increasingly integrated through tourism into the national economy. The mobilisation of tourism to achieve higher levels of ethnic autonomy and empowerment, as is evident in some parts of Australia and New Zealand (Weaver 2010a), has not yet occurred in southern China.

Museums

Unlike battlefields, museums are not site specific, and almost any community can augment their tourism resource inventory by assembling and presenting collections of locally significant artefacts. Museums can range in scale from high-profile, internationally known institutions such as the British Museum in London and the Smithsonian complex in Washington DC, to lesser known city sites such as the National Wool Museum in Geelong, Victoria, and small community museums in regional towns such as Gympie in Queensland. That museums differ widely in the way that items are selected, displayed and interpreted is an aspect of these attractions that has important implications for their market segmentation and marketing. Recent trends include the movement towards ‘hands-on’ interactive interpretation as a way of accommodating a new and more demanding generation of leisure visitors (Kotler, Kotler & Kotler 2008).

Contemporary

Most contemporary attractions have some historical component, and it is even becoming increasingly common to describe phenomena from the latter half of the twentieth century as contemporary heritage, which further blurs the boundaries between past and present. To this category can be added the few remaining motels in North America and elsewhere built during the 1950s and 1960s in the futuristic ‘Googie’ style of architecture, which are the objective of much interest on the part of preservationists and historians of modernism (Hastings 2007) (see the case study at the end of this chapter). Ethnic neighbourhoods and gastronomic experiences, similarly, embody at least some history/heritage element as part of their attractiveness, but still situate comfortably as contemporary phenomena for classification purposes.

Ethnic neighbourhoods

Large cities in Australia, Canada, the United States and Western Europe are becoming increasingly diverse as a result of contemporary international migration patterns. This has led to the emergence of neighbourhoods associated with particular ethnic groups and their reinforcement through explicit or implicit policies of multiculturalism (Collins & Jordan 2009). For many years such areas were alienated from the broader urban community, but now the Chinatowns of San Francisco, Sydney, Vancouver, New York and Toronto — to name just a few — have evolved into high-profile tourist 130districts. This trend has been assisted by the placement of Chinese language street signs and the approval of Asian-style outdoor markets and other culturally specific features, such as gateway arches. The effect is to provide tourists (as well as local residents) with an experience of the exotic, without having to travel far afield. A surprising development has been the transformation of ghetto neighbourhoods such as Soweto, South Africa, into destinations that are attractive to white visitors whose negative images of such vibrant places are subsequently challenged (Booyens 2010, Frenzel, Koens & Steinbrink 2012).

Food and drink

While taken for granted as a necessary consumable in any tourism experience, food is increasingly becoming an attraction in its own right, as illustrated by the experience of all the ethnic urban neighbourhoods mentioned above and numerous other destinations (Hall & Gossling 2012). In places such as Singapore, culinary tourism is encouraged not just to compensate for the lack of iconic attractions but also to reinforce the country’s desired image of harmonious multiculturalism (Henderson 2004). For any place, food and drink are means by which the tourist can literally consume the destination, and if the experience is memorable, it can be exceptionally effective at inducing the highly desired outcomes of repeat visitation and favourable word-of-mouth promotion. Increasingly prevalent are strategies to feature distinctive local food and drink, thereby emphasising the destination’s unique sense of place while simultaneously encouraging economic, cultural and environmental sustainability (Hall & Gossling 2012).

A particularly well-articulated form of culinary tourism in some destinations is wine tourism (Croce & Perri 2010). Scenic winescapes are the focus of tourism activity in well-established locations such as the Napa Valley of California, the Hunter Valley of New South Wales, the Clare and Barossa Valleys of South Australia, the Margaret River region of Western Australia and in emerging locations such as Canada’s Niagara Peninsula (Bruwer & Lesschaeve 2012). The more established regions have all benefited from a pattern of producing reliably high quality wines, a strong and positive market image, well-managed cellar door operations, and exurban locations. However, while tourism seems to be highly compatible with the wine industry, attendant challenges include:

internal competition among producers that impedes collective marketing and management

increasing competition from new regions that diverts visitors and dissuades repeat visitation

difficulties in concurrently managing the tourism and production aspects of business

increased urbanisation and exurbanisation that reduce the winescape’s aesthetic appeal and relaxed lifestyle.

Economic activity

‘Living’ economic activities such as mining, agriculture and manufacturing are often taken for granted by the local community, and particularly by the labour force engaged in those livelihoods. However, these activities can also provide a fascinating and unusual experience for those who use the associated products but are divorced from their actual production. At a deeper level, the widespread separation of modern society from the processes of production in the postindustrial era, and the subsequent desire 131to participate at least indirectly in such activities, may help to explain the growing popularity of factory, mine and farm tours.

Canals and railways

Recreational canals and railways provide excellent examples of functional adaptation (the use of a structure for a purpose other than its original intent). As with factory, mine and farm tours, such adaptations are associated with the movement from an industrial to a postindustrial society, in which many canals and railways are now more valuable as sites for recreation and tourism than as a means of bulk transportation for industrial goods — their original intent. England is an area where pleasure-boating on canals is especially important, as the Industrial Revolution left behind a legacy of thousands of kilometres of now defunct canals, which have proven ideal for accommodating small pleasure craft (Fallon 2012). A similar phenomenon is apparent in North American locations such as the Trent and Rideau Canals (Ontario, Canada) and the Erie Canal in New York State.

Specialised recreational attractions (SRAs)

Of all categories of tourist attraction, specialised recreational attractions (SRAs) are unique because they are constructed specifically to meet the demands of the tourism and recreation markets. With the exception of ski lifts and several other products that require specific environments, SRAs are also among the attractions least constrained by context and location. Their establishment, in other words, does not usually depend on particular physical conditions. SRAs are in addition the attraction type most clearly related to the tourism industry, since they mostly consist of privately owned businesses (the linear SRAs discussed below are one exception).

Golf courses

Golf courses are an important SRA subcategory for several reasons, including:

the recent proliferation of golf facilities worldwide (more than 30 000 by the early 2000s)

the relatively large amount of space that they occupy both individually and collectively

their association with residential housing developments and integrated resorts

their controversial environmental impacts, especially in water-scarce destinations such as Cyprus (Boukas, Boustras & Sinka 2012)

their status as major event venues (e.g. golf tournaments, wedding receptions).

In addition, high concentrations of golf activity, in areas such as Palm Springs, California, and Orlando, Florida, have led to the appearance of golfscapes, or landscapes where golf courses and affiliated developments are a dominant land use. The Gold Coast is the best Australian example of a golfscape, with some 30 courses available within council boundaries, and others approved but not (yet) constructed.

Casinos

For many years, casinos were synonymous with Monte Carlo, Las Vegas and few other locations. However, casinos have proliferated well beyond these traditional strongholds as governments have become more aware of, and dependent on gaming-based revenues. Casinos are now a common sight on North American Indian Reserves, in central cities (e.g. Melbourne’s Crown Casino and Brisbane’s Treasury Casino), and as Mississippi River-style gambling boats in the American South and Midwest. One resultant economic implication of this proliferation is the dilution of potential markets. 132An interesting development is the transformation of Macau, China into the Chinese version of Las Vegas (Wan & Li 2013). Increasing competition has prompted the Las Vegas tourism industry to erect ever larger and more fantastic themed casino hotels (e.g. Excalibur, Luxor and MGM Grand) which increasingly blur the distinction between accommodation and attraction. The concurrent development of fine dining opportunities is an additional attempt to attract new visitor segments. Though ideally intended to attract external revenue, casinos such as Jupiters Casino on the Gold Coast are also attractive to local residents, and their presence is often therefore controversial due to the possibility of negative social impacts (see chapter 9).

Theme parks

Theme parks are large-scale, topical and mostly exurban SRAs that contain numerous subattractions (e.g. rides, shows, exhibits, events) intended to provide family groups with an all-inclusive, all-day or multi-day recreational experience. The Disney-related sites (e.g. Disneyland at Anaheim, California; DisneyWorld at Orlando, Florida; and Disneyland Paris) are the best known international examples, while the Gold Coast theme parks (e.g. Dreamworld, Sea World and Warner Bros. Movie World) are the best known Australian examples. Theme parks provide a good illustration of social engineering in that they purport to offer thrilling and spontaneous experiences, yet in reality are hyper-regulated and orchestrated environments that maximise opportunities for retail expenditure by visitors (Rojek 1993). It is largely for this same gap between perception and reality that many of the indigenous villages in China’s Yunnan Province have been described as ‘ethnic theme parks’ (Yang 2010).

Scenic highways, bikeways and hiking trails

Linear recreational attractions are sometimes the result of functional adaptation, as for example canals (see above) and bicycle and walking trails that are constructed on the foundations of abandoned railway lines. The Rails to Trails Conservancy is a US-based organisation that specialises in such conversions. In other cases linear SRAs are custom built to meet specific recreational and tourism needs. The Blue Ridge Parkway and Natchez Trace are US examples of custom-built scenic roadways, while the Appalachian Trail is a well-known example of a specialised long-distance walking track (Littlefield & Siudzinski 2012). A variation of the road theme is the multipurpose highway that is designated, and modified accordingly, as a scenic route. A nostalgia-focused US example that illustrates the concept of contemporary heritage is the old Route 66 from Chicago to Los Angeles, which was the main way of travelling from the north-eastern United States to California in the 1950s (Caton & Santos 2007). Australian examples include Victoria’s Great Ocean Road and the Birdsville Track from Marree (SA) to Birdsville (Qld).

Ski resorts

More than most SRAs, ski resort viability is dependent on the availability of specific climatic and topographical conditions, although the invention of affordable snow-making technology greatly facilitated the spread of the industry into regions otherwise unsuitable. Famous ski resorts such as Vail and Aspen (Colorado, USA), Zermatt and St. Moritz (Switzerland) and Whistler (Canada) attest to the transformation of formerly remote and undesirable alpine locales into popular pleasure periphery destinations. A process of consolidation, however, is now evident, with the number of ski areas in the United States declining from 745 to 509 between 1975 and 2000 (Clifford 2002). Concurrently, the average size of resorts has increased and 133corporate ownership has become prevalent. As with golf courses, the profitability of the contemporary ski megaresort is increasingly dependent on revenues from affiliated housing developments, in which case the actual ski facilities serve primarily as a ‘hook’ to attract real-estate investors. A longer-term issue that may affect the survival of many ski resorts is climate change, especially in areas of already marginal snow cover such as the Australian Alps (Pickering 2011).

Retail

Under certain conditions, retail goods and services, like food, are major tourist attractions in their own right, and not only an associated service activity. Singapore and Hong Kong are South-East Asian examples of destinations that offer shopping opportunities as a core component of their tourism product. In cities such as Kuala Lumpur (Malaysia), shopping malls are built into large hotels to create an integrated accommodation–shopping complex. In New Zealand, shopping competes with dining as the main activity undertaken by inbound tourists (see table 5.1).

Mega-malls

The ‘mega-mall’ phenomenon has historically been associated with North America, where the West Edmonton Mall (Canada), the Mall of the Americas (Minneapolis) and other complexes vied to be recognised as the world’s largest shopping centre, often through the display of a theme park environment. In recent years, East Asian malls have competed exclusively for this title. As with theme parks and large casinos, mega-malls are composite attractions that contain numerous individual subattractions, all designed to maximise the amount of time that visitors remain within the facility and the amount of money they spend. Similarly, they are usually contrived in character, incorporating fake Italian townscapes, ski slopes (as in Dubai) or exotic South Pacific themes.

Markets and bazaars

‘Colourful’ Caribbean markets and ‘exotic’ Asian bazaars are generic tourism icons of their respective destination regions. The ability to compromise between authenticity (which may repel some tourists) and a comfortable and safe environment for the conventional tourist is a major challenge for operators of market and bazaar attractions. Within Australia, country or ‘farmers’ markets in communities such as Mount Tamborine and Eumundi (Queensland) are major local attractions, especially for domestic tourists.

Cultural events

Cultural events can be categorised in several ways, including the extent to which they are regular or irregular in occurrence (e.g. the Summer Olympics every four years versus one-time-only special commemorations) or location (the British Open tennis tournament held at Wimbledon versus the changing Olympics site). Cultural events range in size from a small local arts festival to international mega-events such as the football World Cup. In addition, events may be ‘single destination’ (e.g. Wimbledon) or ‘multiple destination’ in space or time (e.g. the Olympics sites spread over a region or the circuit-based Tour de France bicycle race). Finally, thematic classification assigns events to topical categories such as history, sport, religion, music and arts. For tourism sites such as theme parks and historical destinations, periodic events are an important supplementary attraction that add to product diversity and offer a distraction from routine. They may also serve as a management device that redistributes visitors 134in a more desirable way both in time and space. As with museums, communities have the ability to initiate cultural events by creatively capitalising on available local resources.

Historical re-enactments and commemorations

The re-creation of historical events can serve many purposes in addition to its superficial value as a tourist attraction. Participants may be primarily motivated by a deep-seated desire to connect with significant events of the past, while governments often encourage and sponsor such performances to perpetuate the propaganda or mythological value of the original event, especially if the recreations or commemorations occur at the original sites. Re-enactments associated with the landings of Captain Cook featured prominently in the 1988 Bicentenary commemorations in Australia, although their association with the post-1788 Aboriginal dispossession injected an element of controversy. The period from 2011 to 2018 is an especially active one due to commemorations associated first with the 150th anniversary of the American Civil War (1861–65) and the centenary of World War I (1914–18).

Sporting events

The modern Olympic Games are the most prestigious of all sporting events, although the football World Cup is emerging as a legitimate contender for the title following highly successful recent events and the status of football as the unofficial global sport. That the World Cup and the Olympics do not take place in the same year is a deliberate attempt to avoid competing mega-event hype and coverage. Major sporting events are exceptional in the degree to which they attract extensive media attention, and the number of television viewers far outweighs the on-site audience. These events are therefore additionally important for their potential to induce some of the television audience (which may number several billion consumers) to visit the host city, thereby creating a post-event ripple effect.

The fierce competition that accompanies the selection of host Olympic cities or World Cup nations is therefore as much about long-term image enhancement and induced visitation as it is about the actual event (Hinch & Higham 2011). The 2000 Sydney Games were highly symbolic because of their occurrence at the turn of the millennium and their role in positioning the host city as a globalised ‘world city’. The 2008 Beijing Games were unofficially seen as heralding China’s emergence as a world sporting (and economic) power, and the 2012 London Games were credited with a revitalisation effect for the host city as well as the host country.

World fairs

While less prestigious than the Olympics, world fairs (designated as such by an official organisation similar to the International Olympic Committee, or IOC) also confer a significant amount of status and visibility to host cities. Expo 2010 in Shanghai, China, for example, attracted an estimated 70 million mostly domestic visitors and was touted as confirming Shanghai’s status as a major world city (Xinhua English News 2010).

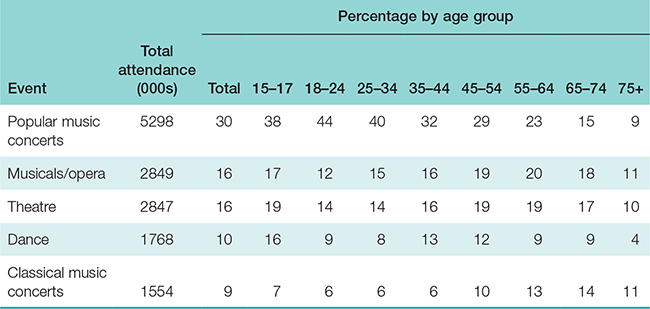

Festivals and performances

Most countries, including Australia, host an extremely large and diverse number of festivals and performances. Attendance by Australians at various cultural performances attests to their magnitude and broad levels of appeal to different age groups (see table 5.2). As mentioned earlier, destinations have considerable ability to establish 135festival- and performance-type events, since these can capitalise on anything from a particular local culture or industry to themes completely unrelated to the area. Examples of the unrelated themes include the Elvis Festival held annually in the central New South Wales town of Parkes and the highly popular Woodford Folk Festival, held annually in the Sunshine Coast hinterland of Queensland. The latter festival could just as easily have been located on any one of a thousand similar sites within an easy drive from Brisbane. In other cases, festivals are more associated with particular destination qualities. The Barossa Vintage Festival in South Australia is a well-known Australian example that capitalises on the local wine industry, while the Queensland town of Gympie leveraged its strong rural identity and lifestyle to cultivate a major country music festival (see Managing tourism: Building social capital with the Gympie Music Muster).

managing tourism

![]() BUILDING SOCIAL CAPITAL WITH THE GYMPIE MUSIC MUSTER

BUILDING SOCIAL CAPITAL WITH THE GYMPIE MUSIC MUSTER

The Gympie Music Muster, a major country music event held every year since 1982 in the Queensland country town of Gympie, demonstrates how local cultural and economic capital — in this case ‘countryside capital’ — can be harnessed to create an enduring tourist attraction that in turn contributes social capital to the community (Edwards 2012). Gympie (population 18 000) is not only an important agricultural service centre, but also the home of the prominent country music artists the Webb brothers, who held the first Muster on their cattle property after having been involved in various local country music events since the 1940s. In 1993, 47 000 people attended the Muster, including many grey nomads from nearby south-east Queensland. By then, it had been moved to a permanent site in a nearby State Forest Park to accommodate the growing attendance, and was recognised as a nationally important event. Since its inception, the local community has played a prominent role, providing 1500 volunteers a year from 50 local non-profit organisations. These organisations have been strengthened through payments generated by entry fees and other visitor expenditures, as well as their own fundraising activities during the event. Volunteers also benefit from seeing and meeting the performers free of charge. A second way in which new capital has been developed has been through the sense of community and unity generated from collaboration among the organisations and from the pride created by the popular festival. Volunteers are regularly consulted in event planning and feel a sense of ownership and common cause. These first two forms of capital create a third level of exchange — ‘social capital’. This comprises the social networks and trust created within the community that facilitate ongoing cooperation. Social capital, for example, has used the Muster as leverage to create two permanent country music institutions, the Australian Institute of Country Music (established in 2001) and the Country Music School of Excellence (established in 2003), both of which generate their own tourism activity throughout the year.

TABLE 5.2 Attendance by age group at selected cultural events in Australia, 2009–10

Source: Data derived from ABS (2010)

Attraction attributes

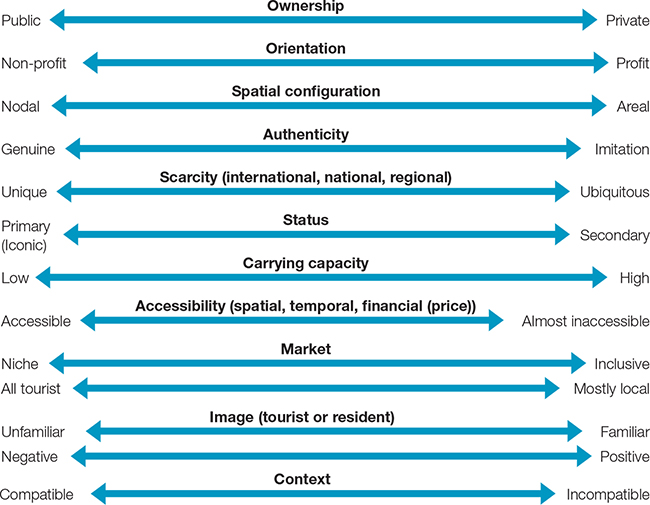

Destination managers, as stated earlier, should compile an inventory of their tourism attractions as a prerequisite for the effective management of their tourism sector. It is not sufficient, however, just to list and categorise the attractions. Managers must also periodically assess their status across an array of relevant attraction attributes to inform appropriate planning and management decisions (see figure 5.3). A spectrum is used in each case to reflect the continuous nature of these variables. Each of the attraction attributes will now be considered, with no order of importance implied by the sequence of presentation. Image is an important attraction attribute, but is addressed elsewhere in the text in some detail (see chapters 4 and 7).

Ownership

The ownership of an attraction significantly affects the planning and management process. For example, the public ownership of Lamington National Park, in the Gold Coast hinterland, implies the injection of public rather than private funding, a high level of government decision-making discretion and the assignment of a higher priority to environmental and social impacts over profit generation. Public ownership also suggests an extensive regulatory environment and long-term, as opposed to shorter-term, planning horizons. It is for this reason that researchers differentiate between public and private protected areas, with the latter becoming increasingly important as vehicles for conservation and recreation as funding for public entities continues to stagnate (Buckley 2009).

Orientation

An emphasis on profitability is affiliated with, but not identical to, private sector ownership. Revenue-starved governments may place more stress on profit generation, which in turn modifies many management assumptions and actions with respect to the attractions they control. Among the possible implications of a profit reorientation in a national park are the introduction of higher user fees, an easing of visitor quotas, greater emphasis on visitor satisfaction, outsourcing of basic management and 137maintenance tasks, and increased latitude for the operation of private concessions. The national park, in essence, becomes a ‘business’ and its visitors ‘customers’ who must be satisfied.

FIGURE 5.3 Tourist attraction attributes

Spatial configuration

Geographical shape and size have important managerial implications. Spatially extensive linear SRAs such as the Appalachian Trail (United States), for example, may cross a large number of political jurisdictions, each of them having some influence therefore over the management of the trail. In addition, long-distance walking trails in particular pass through privately owned land for much of their length, which renders them susceptible to relocation if some landowners decide that they no longer want the trail to pass through their property because of security, liability or vandalism concerns. In the United Kingdom, the status of public walking trails on private property has become a highly contentious and politically charged issue. Linear SRAs are also likely to share extensive borders with adjacent land uses — such as forestry, military bases and mining — that may not be compatible with tourism or recreation. There is potential for conflict and dissatisfaction from the fact that these trails, roads and bikeways rely to a large extent on the scenic resources of these adjacent landscapes, yet the latter are vulnerable to modification by forces over which the attraction manager has no control. Planting vegetation to hide these uncomplementary modifications may be the only practical management option under such circumstances.

In contrast, a circular or square site (e.g. some national parks) reduces the length of the attraction’s boundary and thus the potential for conflict with adjacent land uses. 138This also has practical implications in matters such as the length of boundary that must be fenced or patrolled. The classification of a site often depends on the scale of investigation. For example, a regional strategy for south-east Queensland would regard Dreamworld as an internally undifferentiated ‘node’ or ‘point’, whereas a site-specific master plan would regard the same attraction as an internally differentiated ‘area’.

Authenticity

Whereas ownership, orientation and spatial configuration are relatively straightforward, ‘authenticity’ is a highly ambiguous and contentious attribute that has long been the subject of academic attention (Cohen & Cohen 2012). An exhaustive discussion is beyond the scope of this book, but it suffices to say that authenticity is concerned with how ‘genuine’ an attraction is as opposed to imitative or contrived. This is not to say, however, that contrivance is necessarily a negative characteristic. For example, the 40 000-year-old Neolithic cave paintings at Lascaux (France) were so threatened by the perspiration and respiration of tourists that an almost exact replica was constructed nearby for viewing purposes. Whether the replica is seen in a positive or negative light depends on how it is presented and interpreted; if the tourist is made aware that it is an imitation, and that it is provided as part of the effort to preserve the original while still providing a high quality educational experience, then the copy may be perceived in a very positive light. Similarly, the mega-casinos of Las Vegas offer a contrived experience, but this is not usually problematic since patrons recognise that contrivance and fantasy are central elements of their Vegas tourist experience (see chapter 9).

The issue of authenticity is associated with sense of place, an increasingly popular management concept defined as the mix of natural and cultural characteristics that distinguishes a particular destination from all other destinations, and hence positions it as ‘unique’ along the scarcity spectrum. Sense of place is strongly associated with place attachment and place loyalty behaviour (e.g. repeat visitation) in diverse settings — for example, South Australian dive sites (Moskwa 2012).

Scarcity

An important management implication of scarcity is that a very rare or unique attraction is likely to be both highly vulnerable and highly alluring to tourists as a consequence of its scarcity, assuming that it also has innate attractiveness. At the other end of the spectrum are ubiquitous attractions such as golf courses or theme parks; that is, those that are found or can be established almost anywhere.

Status

A useful distinction can be made between primary or iconic attractions and secondary attractions, which tourists are likely to visit once they have already been drawn to a destination by the primary attraction. A destination may have more than one primary attraction, as with the Eiffel Tower and Louvre in Paris, or the Opera House and harbour in Sydney. One potential disadvantage of iconic attractions is their power to stereotype entire destinations (e.g. the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Swiss Alp villages, the Pyramids of Egypt, or the Great Wall of China). Another potential disadvantage is the negative publicity and loss of visitation that may occur if an iconic attraction is lost due to fire, natural forces or other factors, prompting managers in some cases to try to resurrect such sites as ‘residual attractions’ focused, for example, on commemorations, re-creations, a dedicated museum, or a memorial trail (Weaver & Lawton 2007).139

Carrying capacity

Carrying capacity is difficult to measure since it is not a fixed quality. A national park may have a low visitor carrying capacity in the absence of tourism-related services, but a high visitor carrying capacity once a dirt trail has been paved with cobblestones and biological toilets installed to centralise and treat tourist wastes. In such instances of site hardening, managers must be careful to ensure that the remedial actions themselves do not pose a threat to the site or to the carrying capacity of affiliated resources such as wildlife (see chapters 9 and 11). It is crucial that managers have an idea of an attraction’s carrying capacity at all times, so that, depending on the circumstances, appropriate measures can be taken to either increase this capacity or reduce the stress so that the existing carrying capacity is not exceeded.

Accessibility

Accessibility can be measured variably in terms of space, time and affordability. Spatial access only by a single road will have the positive effect of facilitating entry control, but the negative effects of creating potential bottlenecks and isolating the site in the event of a flood or earthquake. Another dimension of spatial accessibility is how well an attraction is identified on roadmaps and in road signage. Temporal accessibility can be seasonal (e.g. an area closed by winter snowfalls) or assessed on a daily or weekly basis (hours and days of operation). Affordability is important in determining likely markets and visitation levels. All three dimensions should be assessed continually as aspects of an attraction that can be manipulated as part of an effective management strategy.

Market

Destination and attraction markets often vary depending on the season, time of day, cost and other factors. One relevant dimension is whether the attraction appeals to the broad tourism market, as theme parks such as Disney World attempt to do, or to a particular segment of the market, as with battle re-enactments or hunting (see chapter 6). This dictates the type of marketing approach that would be most appropriate (see chapter 7). A second dimension identifies sites and events that are almost exclusively tourist-oriented, as opposed to those that attract mostly local residents. Because of the tendency of clientele to be mixed to a greater or lesser extent, the all-encompassing term ‘visitor attraction’ is often used in preference to the term ‘tourist attraction’. Positive and negative impacts can be associated with both tourist-dominant and resident-dominant attractions. For instance, an exclusively tourist-oriented site may generate local resentment but contain negative impacts to the site itself. The mixing of tourists and locals in some circumstances can increase the probability of cultural conflict, but can also provide tourists with authentic exposure to local lifestyles and opportunities to make new friends (chapter 9).

Context

Context describes the characteristics of the space and time that surround the relevant site or event and, as such, is an attribute that considers the actual and potential impacts of external systems. An example of a compatible external influence is a designated municipal conservation area that serves as a buffer zone surrounding a more environmentally sensitive national park. An incompatible use might be houses hosting domestic pets and exotic plants that may undermine native biodiversity in an adjacent park. The influence of temporal context is demonstrated by a large sporting event that 140is held shortly after a similar event in another city, which could either stimulate or depress public interest depending on the circumstances.

THE TOURISM INDUSTRY

THE TOURISM INDUSTRY

The tourism industry, as described in chapter 2, includes the businesses that provide goods and services wholly or mainly for tourist consumption. Some but not all attractions belong to the tourism industry (or industries). It is worth reiterating that some aspects of the tourism industry are relatively straightforward (e.g. accommodation and travel agencies), but others (e.g. transportation and restaurants) are more difficult to differentiate into their tourism and nontourism components. In addition, commercial activities such as cruise ships and integrated resorts do not readily allow for the isolation of accommodation, transportation, food and beverages, and shopping as distinct components since they usually provide all of these in a single packaged arrangement.

Travel agencies

More than any other tourism industry sector, travel agencies are associated with origin regions (see chapter 2). Their primary function is to provide retail travel services to customers on a commission basis from cruise lines and other tourism sectors or on a fee basis from customers directly. Travel agents in addition normally offer ancillary services such as travel insurance and passport/visa services. As such, they are an important interface or intermediary between consumers and other tourism businesses. Often overlooked, however, is the critical role of travel agents in shaping tourism systems by providing undecided consumers with information and advice about prospective destinations. Furthermore, travel agents can provide invaluable feedback to destination managers because of their sensitivity to market trends and post-trip tourist attitudes about particular destinations and services.

Disintermediation and decommissioning

All these traditional assumptions about the role and importance of travel agents within tourism systems have been challenged by the ongoing phenomenon of disintermediation, which is the removal of intermediaries such as travel agents from the distribution networks that connect consumers (i.e. the tourist market) with products (e.g. accommodations and destinations). This is associated with the rise of the internet, which allows hotels, carriers and other businesses to offer their products through ecommerce directly to consumers in a more convenient and less expensive package (cheaper because it eliminates the agent’s commission). The internet, in addition, has spawned the creation of specialised ‘e-travel agencies’ such as Travelocity and Expedia. By 2010, it was estimated that more than one-half of all leisure trips and 40 per cent of all business trips were booked online, for an estimated value of US$256 billion or about one-third of all travel and tourism sales (WTTC 2011).

An added challenge has been the process of decommissioning, which began in the mid-1990s, wherein airlines no longer pay a standard commission (often 10 per cent) to travel agents in exchange for airfare bookings. Disintermediation and decommissioning have combined with the market uncertainty that followed the 2001 terrorist attacks to create an era of unprecedented challenge for conventional travel agencies in certain countries, although some businesses have performed exceptionally well despite these adverse circumstances. In the United States, where both processes are more 141advanced, successful travel agencies tend to emphasise personalised customer service, employee enrichment initiatives, peer networking and the fostering of a climate of learning among employees as part of a broader strategy of continuous relationship building (Weaver & Lawton 2008). Most have also embraced internet-based technologies as an effective way of facilitating these strategies and complementing quality face-to-face interactions with clients (Lawton & Weaver 2009).

Transportation

The overriding trend in transportation over the past century (see chapters 2 and 3) is the ascendancy of the car and the aeroplane at the expense of water- and rail-based transport. The technological and historical aspects of these trends have already been outlined in earlier chapters, and the sections that follow focus instead on contemporary industry considerations.

Air

As a commercial activity, air transportation is differentiated between scheduled airlines (with standard and budget or low-cost variants), charter airlines and private jets. The last category is by far the smallest and most individualised. The major difference between the first two is the flexibility of charter schedules and the ability of charters to accommodate specific requests from organisations or tour operators.

Airline alliances

A distinctive characteristic of the airline industry is the formation of alliances such as the Star Alliance, oneworld and SkyTeam. As of 2013, these alliances accounted for about three-quarters of all major airlines. Purportedly established on the premise that individual airlines can no longer provide the comprehensive array of services demanded by the contemporary traveller, these alliances offer:

expanded route networks

ease of transfer between airlines

integrated services

greater reciprocity in frequent flier programs and lounge privileges (Fyall & Garrod 2005).

However, more frequent code-sharing (i.e. two airlines sharing the same flight) also means fewer flight options, higher prices (because of reduced competition) and more crowded flights for consumers.

Deregulation

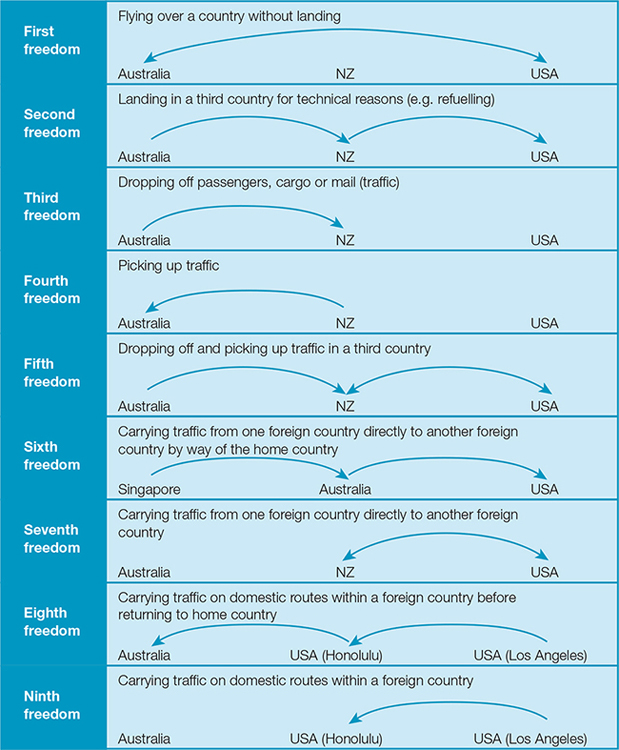

Deregulation (the removal or relaxation of regulations) is intended to introduce or increase competition within the air transportation sector. Associated with deregulation is the increased application of the so-called seventh, eighth and ninth freedoms of the air, which respectively allow a carrier based, for example, in Australia to carry passengers between two other countries and to carry passengers on domestic routes within another country (see figure 5.4). Illustrating the ninth freedom is Ryanair, a low-cost Irish airline that maintains an extensive network of routes within Italy. Although not aimed at this level yet, the open skies aviation agreement signed in February 2008 between Australia and the USA effectively ended the trans-Pacific monopoly of United Airlines and Qantas by allowing the market rather than government to dictate the most efficient structure of the air transit network that connects the two countries.142

FIGURE 5.4 Freedoms of the air

Privatisation

Privatisation, or the transfer of publicly owned airlines to the private sector, is a trend closely related to deregulation. This can be undertaken (a) as a wholesale transformation, (b) as a partial measure achieved through the sale of a certain portion of shares, or (c) through the subcontracting of work. The main rationale for privatisation, as with open skies agreements, is the belief that the private sector is more efficient at providing commercial services such as air passenger transportation. One potential concern in such developments is the increased likelihood that privatised airlines will eliminate unprofitable routes vital to regional or rural destinations. In contrast, national carriers are usually mandated in the broader ‘national interest’ to operate such marginal routes despite their unprofitable returns.

143

Low-cost carriers

The emergence of low-cost carriers (also known as ‘budget’ or ‘no-frills’ airlines) is another consequence of deregulation and one that has posed a substantial threat to the traditional full-service airlines as they account for a growing proportion of all passenger loads. Low fares, unsurprisingly, are the main reason why almost one-half of travellers cite a preference for low-cost carriers, which eliminate many traditional services (e.g. meals, free baggage allowances), tend to focus on short-haul routes, and rely heavily on internet bookings (Yeung, Tsang & Lee 2012). Some traditional airlines have responded by forming their own low-cost subsidiaries. Scoot Airlines, for example, was established by Singapore Airlines in 2011 to compete in Asia with more established low-cost carriers such as AirAsia and Jetstar.

Road

Only certain elements of the road-based transportation industry, including coaches, caravans and rental cars, are strongly affiliated with the tourism industry. Coaches remain a potent symbol of the package tour both in their capacity as tour facilitators and as transportation from airport to hotel. Caravans remain popular because of their dual accommodation and transportation functions. This mode of transport is highly appealing to grey nomads, or older adults who take extended recreational road trips during their retirement (Patterson, Pegg & Litster 2011). The car and the aeroplane in many contexts are seen as competing modes of transportation. However, the rental car industry (e.g. Hertz, National, Avis, Budget) has benefited from the expansion of air transportation, as many passengers appreciate the flexibility of having access to their own vehicle once they arrive at a destination.

Railway