34. Adding a New Disk Drive to an Ubuntu System

One of the first problems encountered by users and system administrators these days is that systems tend to run out of disk space to store data. Fortunately disk space is now one of the cheapest IT commodities. In the next two chapters we will look at the steps necessary to configure Ubuntu to use the space provided via the installation of a new physical or virtual disk drive.

34.1 Mounted File Systems or Logical Volumes

There are two ways to configure a new disk drive on an Ubuntu system. One very simple method is to create one or more Linux partitions on the new drive, create Linux file systems on those partitions and then mount them at specific mount points so that they can be accessed. This approach will be covered in this chapter.

Another approach is to add the new space to an existing volume group or create a new volume group. When Ubuntu is installed with the logical volume management option selected a volume group is created and named vgubuntu. Within this volume group are two logical volumes named root and swap_1 that are used to store the / and swap partitions respectively. By configuring the new disk as part of a volume group we are able to increase the disk space available to the existing logical volumes. Using this approach we are able, therefore, to increase the size of the /home file system by allocating some or all of the space on the new disk to the home volume. This topic will be discussed in detail in “Adding a New Disk to an Ubuntu Volume Group and Logical Volume”.

34.2 Finding the New Hard Drive

This tutorial assumes that a new physical or virtual hard drive has been installed on the system and is visible to the operating system. Once added, the new drive should automatically be detected by the operating system. Typically, the disk drives in a system are assigned device names beginning hd or sd followed by a letter to indicate the device number. For example, the first device might be /dev/sda, the second /dev/sdb and so on.

The following is output from a typical system with only one disk drive connected to a SATA controller:

# ls /dev/sd*

/dev/sda /dev/sda1 /dev/sda2

This shows that the disk drive represented by /dev/sda is itself divided into 2 partitions, represented by /dev/sda1 and /dev/sda2.

The following output is from the same system after a second hard disk drive has been installed:

# ls /dev/sd*

/dev/sda /dev/sda1 /dev/sda2 /dev/sdb

As shown above, the new hard drive has been assigned to the device file /dev/sdb. Currently the drive has no partitions shown (because we have yet to create any).

At this point we have a choice of creating partitions and file systems on the new drive and mounting them for access or adding the disk as a physical volume as part of a volume group. To perform the former continue with this chapter, otherwise read “Adding a New Disk to an Ubuntu Volume Group and Logical Volume” for details on configuring Logical Volumes.

34.3 Creating Linux Partitions

The next step is to create one or more Linux partitions on the new disk drive. This is achieved using the fdisk utility which takes as a command-line argument the device to be partitioned:

# fdisk /dev/sdb

Welcome to fdisk (util-linux 2.32.1).

Changes will remain in memory only, until you decide to write them.

Be careful before using the write command.

Device does not contain a recognized partition table.

Created a new DOS disklabel with disk identifier 0xbd09c991.

Command (m for help):

In order to view the current partitions on the disk enter the p command:

Command (m for help): p

Disk /dev/sdb: 8 GiB, 8589934592 bytes, 16777216 sectors

Units: sectors of 1 * 512 = 512 bytes

Sector size (logical/physical): 512 bytes / 512 bytes

I/O size (minimum/optimal): 512 bytes / 512 bytes

Disklabel type: dos

Disk identifier: 0xbd09c991

As we can see from the above fdisk output, the disk currently has no partitions because it is a previously unused disk. The next step is to create a new partition on the disk, a task which is performed by entering n (for new partition) and p (for primary partition):

Command (m for help): n

Partition type

p primary (0 primary, 0 extended, 4 free)

e extended (container for logical partitions)

Select (default p): p

Partition number (1-4, default 1):

In this example we only plan to create one partition which will be partition 1. Next we need to specify where the partition will begin and end. Since this is the first partition we need it to start at the first available sector and since we want to use the entire disk we specify the last sector as the end. Note that if you wish to create multiple partitions you can specify the size of each partition by sectors, bytes, kilobytes or megabytes.

Partition number (1-4, default 1): 1

First sector (2048-16777215, default 2048):

Last sector, +sectors or +size{K,M,G,T,P} (2048-16777215, default 16777215):

Created a new partition 1 of type ‘Linux’ and of size 8 GiB.

Command (m for help):

Now that we have specified the partition, we need to write it to the disk using the w command:

Command (m for help): w

The partition table has been altered.

Calling ioctl() to re-read partition table.

Syncing disks.

If we now look at the devices again we will see that the new partition is visible as /dev/sdb1:

# ls /dev/sd*

/dev/sda /dev/sda1 /dev/sda2 /dev/sdb /dev/sdb1

The next step is to create a file system on our new partition.

34.4 Creating a File System on a Disk Partition

We now have a new disk installed, it is visible to Ubuntu and we have configured a Linux partition on the disk. The next step is to create a Linux file system on the partition so that the operating system can use it to store files and data. The easiest way to create a file system on a partition is to use the mkfs.xfs utility:

# apt install xfsprogs

# mkfs.xfs /dev/sdb1

meta-data=/dev/sdb1 isize=512 agcount=4, agsize=524224 blks

= sectsz=512 attr=2, projid32bit=1

= crc=1 finobt=1, sparse=1, rmapbt=0

= reflink=1

data = bsize=4096 blocks=2096896, imaxpct=25

= sunit=0 swidth=0 blks

naming =version 2 bsize=4096 ascii-ci=0, ftype=1

log =internal log bsize=4096 blocks=2560, version=2

= sectsz=512 sunit=0 blks, lazy-count=1

realtime =none extsz=4096 blocks=0, rtextents=0

In this case we have created an XFS file system. XFS is a high performance file system and includes a number of advantages in terms of parallel I/O performance and the use of journaling.

34.5 An Overview of Journaled File Systems

A journaling filesystem keeps a journal or log of the changes that are being made to the filesystem during disk writing that can be used to rapidly reconstruct corruptions that may occur due to events such as a system crash or power outage.

There are a number of advantages to using a journaling file system. Both the size and volume of data stored on disk drives has grown exponentially over the years. The problem with a non-journaled file system is that following a crash the fsck (filesystem consistency check) utility has to be run. The fsck utility will scan the entire filesystem validating all entries and making sure that blocks are allocated and referenced correctly. If it finds a corrupt entry it will attempt to fix the problem. The issues here are two-fold. First, the fsck utility will not always be able to repair damage and you will end up with data in the lost+found directory. This is data that was being used by an application but the system no longer knows where it was referenced from. The other problem is the issue of time. It can take a very long time to complete the fsck process on a large file system, potentially leading to unacceptable down time.

A journaled file system, on the other hand, records information in a log area on a disk (the journal and log do not need to be on the same device) during each write. This is a essentially an “intent to commit” data to the filesystem. The amount of information logged is configurable and ranges from not logging anything, to logging what is known as the “metadata” (i.e. ownership, date stamp information etc), to logging the “metadata” and the data blocks that are to be written to the file. Once the log is updated the system then writes the actual data to the appropriate areas of the filesystem and marks an entry in the log to say the data is committed.

After a crash the filesystem can very quickly be brought back on-line using the journal log, thereby reducing what could take minutes using fsck to seconds with the added advantage that there is considerably less chance of data loss or corruption.

Now that we have created a new file system on the Linux partition of our new disk drive we need to mount it so that it is accessible and usable. In order to do this we need to create a mount point. A mount point is simply a directory or folder into which the file system will be mounted. For the purposes of this example we will create a /backup directory to match our file system label (although it is not necessary that these values match):

# mkdir /backup

The file system may then be manually mounted using the mount command:

# mount /dev/sdb1 /backup

Running the mount command with no arguments shows us all currently mounted file systems (including our new file system):

# mount

sysfs on /sys type sysfs (rw,nosuid,nodev,noexec,relatime,seclabel)

proc on /proc type proc (rw,nosuid,nodev,noexec,relatime)

.

.

/dev/sdb1 on /backup type xfs (rw,relatime,attr2,inode64,logbufs=8,logbsize=32k,noquota)

34.7 Configuring Ubuntu to Automatically Mount a File System

In order to set up the system so that the new file system is automatically mounted at boot time an entry needs to be added to the /etc/fstab file. The format for an fstab entry is as follows:

<device> <dir> <type> <options> <dump> <fsck>

These entries can be summarized as follows:

•<device> - The device on which the filesystem is to be mounted.

•<dir> - The directory that is to act as the mount point for the filesystem.

•<type> - The filesystem type (xfs, ext4 etc.)

•<options> - Additional filesystem mount options, for example making the filesystem read-only or controlling whether the filesystem can be mounted by any user. Run man mount to review a full list of options. Setting this value to defaults will use the default settings for the filesystem (rw, suid, dev, exec, auto, nouser, async).

•<dump> - Dictates whether the content of the filesystem is to be included in any backups performed by the dump utility. This setting is rarely used and can be disabled with a 0 value.

•<fsck> - Whether the filesystem is checked by fsck after a system crash and the order in which filesystems are to be checked. For journaled filesystems such as XFS this should be set to 0 to indicate that the check is not required.

The following example shows an fstab file configured to automount our /backup partition on the /dev/sdb1 partition:

/dev/mapper/vgubuntu-root / ext4 errors=remount-ro 0 1

/dev/mapper/vgubuntu-swap_1 none swap sw 0 0

/dev/sdb1 /backup xfs defaults 0 0

The /backup filesystem will now automount each time the system restarts.

34.8 Adding a Disk Using Cockpit

In addition to working with storage using the command-line utilities outlined in this chapter, it is also possible to configure a new storage device using the Cockpit web console. To view the current storage configuration, log into the Cockpit console and select the Storage option as shown in Figure 34-1:

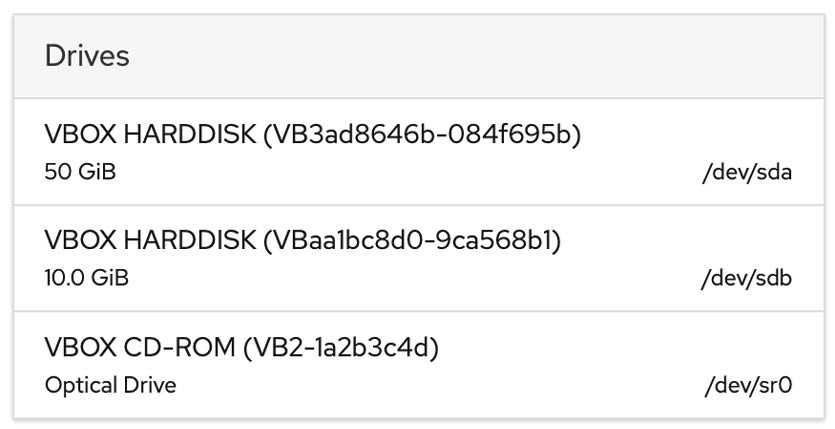

To locate the newly added storage, scroll to the bottom of the Storage page until the Drives section comes into view (note that the Drives section may also be located in the top right-hand corner of the screen):

Figure 34-2

In the case of the above figure, the new drive is the 10 GiB drive. Select the new drive to display the Drive screen as shown in Figure 34-3:

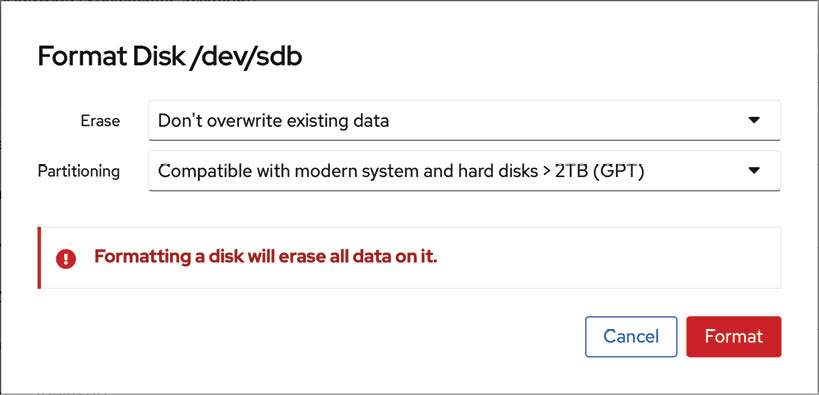

Click on the Create Partition Table button and, in the resulting dialog, accept the default settings before clicking on the Format button:

Figure 34-4

On returning to the main Storage screen, click on the Create Partition button and use the dialog to specify how much space is to be allocated to this partition, the filesystem type (XFS is recommended) and an optional label, filesystem mount point and mount options. Note that if this new partition does not use all of the available space, additional partitions may subsequently be added to the drive. To change settings such as whether the filesystem is read-only or mounted at boot time, change the Mounting menu option to Custom and adjust the toggle button settings:

Figure 34-5

Once the settings have been selected, click on the Create partition button to commit the change. On completion of the creation process the new partition will be added to the disk, the corresponding filesystem created and mounted at the designated mount point and appropriate changes made to the /etc/fstab file.

This chapter has covered the topic of adding an additional physical or virtual disk drive to an existing Ubuntu system. This is a relatively simple process of making sure the new drive has been detected by the operating system, creating one or more partitions on the drive and then making filesystems on those partitions. Although a number of different filesystem types are available on Ubuntu, XFS is generally the recommended option. Once the filesystems are ready, they can be mounted using the mount command. So that the newly created filesystems mount automatically on system startup, additions can be made to the /etc/fstab configuration file.