© 2004 by Ralph W. Lambrecht, all rights reserved

Presentation Is Everything

Mounting and Matting Prints

Solid steps to successful print presentations

In addition to supporting and protecting the print, the main function of the mount is to isolate the print and clear the immediate image surroundings from visual distractions (fig.1), thereby providing an aesthetically pleasing, neutral and complementary viewing environment, without any attempt to compete with the image for attention. A truly successful image can probably stand on its own, but even the best image benefits from appropriate presentation, if we want to portray its full potential. A properly mounted, matted and framed print has clear advantages over its loose counterpart, including focused communication, the perception of increased value, some protection against rough handling and optimized longevity. When processed to archival standards and competently mounted with quality materials, an appropriately stored and displayed print can be admired for several lifetimes.

Description

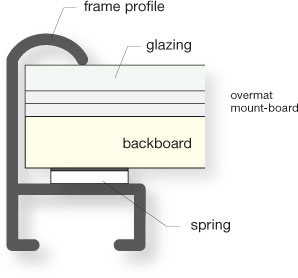

Fig.2 shows the basic components of mounted artwork ready for framing. First, the print is securely attached to the mount-board using dry-mount adhesive or suitable alternate means. Then, the mounted print is covered and protected with a window overmat, as well as supported by a backboard. The difference between mounting and matting board is in the way they are applied, either carrying or overmatting the print, but some manufacturers make significant material differences between the two. Unless, for creative reasons, you cannot live without a color or texture difference between mount-board and overmat, I suggest using the same material for both to give the print consistent protection and appearance.

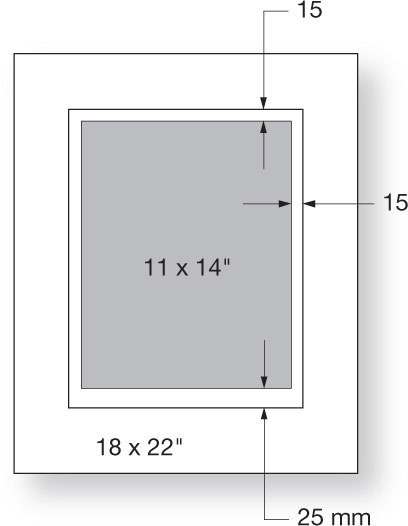

fig.1 The mount supports and protects the print, while clearing the immediate image surroundings from visual distractions, without competing for attention.

fig.2 The basic components of dry-mounted artwork ready for framing. The print is securely attached to the mount-board, using an adhesive tissue or film. The mounted print is then covered and protected by a window overmat, and supported with a backboard.

Mounting Styles

There are various mounting styles to choose from, the selection of which too often depends on the type of presentation and longevity requirements. They all differ from one another in the material choice, the size of the mount-board, the attachment method for the print, a preference for an overmat and the equipment required to put it all together. Some mounting styles aim for the most favorable print presentation and protection, while also providing best possible archival conditions; others just aim to improve short-term print presentation without any claims of permanence. This chapter offers an overview of several mounting styles but concentrates on archival mounting and professional print presentation.

When the print and mount-board are of the same dimensions, it is called a flush or bleed-mount style. This stiffens the prints but offers little protection around the edges. Bleed-mounting also completely fails to isolate the print from potentially disturbing surroundings, because no mount-board is left showing, and as a result, it makes for a rather lackadaisical presentation style. Having said that, I have used bleed-mounting successfully in assembling photographic aids, as shown in ‘How to Build and Use the Zone Ruler’. In all other cases, I prefer a rather wide border around the print, which is referred to as the border-mount style.

To attach the print to the mount-board, we have the option of creating a permanent bond or just loosely holding the print in place and securing its location later with an overmat. Both methods have pros and cons, so before we decide, let us explore each in more detail.

A permanent bond always requires some kind of an adhesive. Stay well away from liquid or spray adhesives. They are extremely messy, make a smooth bond a matter of chance and rarely have any archival properties. Dry adhesives are far better, and there is the choice between cold and hot dry-mounting, which both use an adhesive tissue or film. Dry-mount adhesive, once applied, creates an irreversible bond and acts as a protective layer between mount-board and print. This layer protects the backside of the print from any environmental contamination coming through the backboard and potentially being absorbed by the mount-board, leaving only the print’s image area exposed to air-born contaminants.

In cold dry-mounting, the adhesive is laid upon a release layer and then rolled onto the back of the print. Full adhesion only comes through the application of pressure. The adhesive does not come off on your hands and makes for clean, odorless working. However, the classic permanent bond is only accomplished through hot dry-mounting (see fig.14). It requires the use of an expensive dry-mount press, which securely sandwiches the dry-mount adhesive between the mount-board and the print under pressure, while applying enough heat to melt the adhesive. Some of the molten dry-mount adhesive is then absorbed by the surface fibers of mount-board and print, forming a permanent and waterproof bond between them, once the adhesive has been given enough time to cool and solidify. Dry-mounting makes for a perfectly flat mount with an unrivaled professional look. It is clean, dependable, fully archival, and every serious fine-art photographer is well advised to seriously consider this method. Unfortunately, some print materials do not react well with the heat, and then, the use of cold-mount adhesive might be the better option. Nonetheless, hot dry-mounting is my preferred choice for mounting FB-prints.

There might be one good reason not to dry-mount at all, if your prints are destined for a salon or gallery showing. The person in charge of the exhibition may simply not accept dry-mounted prints. Galleries often present the works of more than one artist and may insist on consistency of presentation between images. To ensure this, they need the flexibility of remounting and reframing your prints at will. The permanency of a dry-mounted bond does not allow this flexibility. To maintain the option of selecting a different mount in the future, we need to select a reversible mounting method. Two different methods are commonly used, hinge-mounting and corner-mounting.

To hinge-mount a print, a piece of tape is used as a flexible hinge; half of it applied to the mount-board and the other half directly to the print. Only use conservation or museum-quality, gummed, acid-free cloth tape with a water-soluble adhesive. Self-adhesive tape is not acceptable, as it can dry out and eventually fail. Of course, the print should feature a white non-image border to provide some room for the tape. The overmat then covers tape and border.

Mounting board, matting board and backing board are terms referring to the ‘raw’ stationery materials used.

Mount-board, mat-board and backboard are usable sheets, cut to size from the above stationery materials. Cutting a window opening into a mat-board turns it into a functional ‘window’ overmat or just a mat.

Mount is a general term, referring to the mounting style or the entire assembly but without the frame.

To corner-mount a print (see fig.16), small corner pockets of acid-free paper are taped to the mount-board, holding the print loosely at all four corners. As with hinge-mounting, the print should feature a white border, so the corner pockets do not infringe into the image area, and the overmat covers the corners, tape and border. Hinge-mounting is simpler, but for non-permanent mounting, I prefer corner-mounting, because it leaves no tape residue on the print and makes freeing it from the mount as simple as slipping it carefully out of the paper pockets.

If the print is dry-mounted and you prefer a plain mount, the mounting effort is finished at this point. Unfortunately, we need to consider that the mounted print has been raised off the mount-board by the combined thickness of the dry-mount adhesive and the print paper itself. This makes the print edges vulnerable to damage from handling and stacking. Therefore, before a mounted print is framed and put behind glass, an overmat with its window opening must be cut and placed on top of the mount-board. This will protect the print from irreparable damage and keep it from rubbing or touching the inner glass surface, allowing it to ‘breathe’ and circumvent the emulsion from sticking to the glass over time. Furthermore, to keep the overmat securely aligned with the print, it helps to hinge-mount it on one side to the mount-board, using acid-free cloth tape. The additional overmat raises the optical appeal of the print. Consequently, an overmat should be considered for both framed and unframed prints alike, in order to make for the finest print presentation possible.

fig.3 To enhance the print presentation and protect the print from physical damage, an overmat with its window opening is prepared and placed on top of the print and mount-board. For a dry-mounted print, the window is cut large enough to provide clearance on all sides of the print. Below the print, a bit more space is needed to allow enough room for print edition number, signature and date.

To give this mounting arrangement an even more pleasing look, it is customary to cut the inner window, exposing the print, with a bevel cutter. The resulting bevel joins the mount-board and overmat smoothly at an angle between 45° and 60°, eliminating harsh and distracting shadows, yet framing the print delicately. The size of the window opening depends on the type of print attachment used. If the print is hinge or corner-mounted, the window needs to be smaller than the image area of the print to cover the tape, corner pockets and print border, and to hold the print firmly in place. If the print is dry-mounted, you have some flexibility in choosing the window dimensions. I cut my windows large enough to provide about 5/8-inch (15 mm) clearance on the sides and on top of the print (see fig.3). Below the print bottom, I allow a bit more space, sufficient to add the print edition number, and to sign and date the print later. I find 3/4 to 1 inch (20-25 mm) to be adequate for that task.

Before deciding which prints to mount and what style to choose, consider that quality print mounting takes time, effort and money, and not every print deserves this treatment. However, if the value of an individual image was mirrored by your choice of print materials and was processed to archival standards, then it makes sense to continue this standard through the mounting and presentation steps. I only mount my best prints, which are targeted for exhibition or sale, and I do it just prior to these events, using only the best materials. It takes less space to store loose prints in archival boxes until they are needed. Mounting valuable prints is a presentation technique, not a storage method. I use RC paper only for preliminary work, such as artwork for magazines or as a give-away for model portfolios. Consequently, I do not mount RC prints. Nevertheless, it can be done if you prefer RC prints, and the techniques described in this chapter work for FB and RC prints alike.

Mounting Materials

Board is manufactured from different paper materials to support varying archival requirements and budgets. Regular illustration board or standard board is made of virgin cellulose fibers (wood pulp). It contains lignin, which forms the cell walls in plants. Untreated, this material contains acid (pH<7.0) and is, consequently, harmful to silver-gelatin prints. Over time, lignin and acid will degrade the artwork. Standard board discolors visibly within a few years, accelerated by temperature, humidity, pollution attack and exposure to light. This can typically be seen at the beveled edges first. Illustration or standard board is a low-budget material and not recommended for our treasured prints.

Conservation board is made of alpha-cellulose wood pulp, which has been chemically treated to eliminate acid and lignin. It gives artwork a higher degree of protection, and FB paper itself is made of this acid-free material. Conservation board is a good choice for photographic prints, providing a professional finish and a minimum level of archival protection. These benefits justify the increase in cost.

Museum board or cotton-rag board is made of 100% cotton fibers, which are naturally acid-free and lignin-free. The term ‘rag’ dates back to the time when cotton rags and cloth were the principal materials used for paper manufacture. Cotton is a time-tested, fade-resistant and durable material, offering the highest level of archival protection. It is used by museums and discerning photographers for the preservation of fine prints. The inherent expense should not stop us from using it for prints of high value.

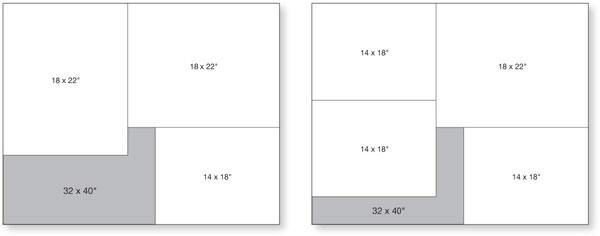

fig.4 Mounting and matting board comes in a variety of full-sheet sizes, with 32x40 inches being the most common dimensions. It is advisable to prepare cutting plans for your favorite mount-board dimensions to minimize waste. Two examples are shown here.

As an alternative to the choices above, some manufacturers offer ‘buffered’ boards. Buffering, or pH-balancing, is an additional fiber treatment to neutralize acid, which might be generated in the future from aging prints or boards, or from environmental pollution. A buffered board or paper has calcium carbonate added to the fibers, which provides an alkaline reserve (pH7.5-9.5), just waiting to counterbalance any potential acid attack in the future. Buffered materials are a good choice, although not in combination with some historic photographic processes, like Cyanotype, because the alkaline environment will actually damage these types of prints.

Dry-mount adhesive is an acid-free, dry acrylic adhesive, available as thermoplastic rolls or sheets in two basic compositions, as tissue or film. Dry-mount tissue has a center carrier of porous or non-porous tissue with adhesive applied to either side of the tissue. Dry-mount film has no carrier tissue at the center; it is pure, non-porous adhesive. Non-porous dry-mount tissue and dry-mount film may trap air or steam between print and adhesive during mounting. This will create objectionable bubbles with RC prints. With FB prints, on the other hand, trapped air has the opportunity to escape through the print. I prefer porous dry-mount tissue, because it works well with both RC and FB prints.

Backing board provides a stiff and flat print support, which is needed to securely frame the mounted artwork. It typically has a rigid foam core, sandwiched between two layers of paper. The foam center is made of extruded polystyrene, an inert and resilient plastic material, which keeps the board light and easy to cut. For archival mounting, the surface papers must be made of the same acid-free and lignin-free material as the mounting and matting board used in order to offer consistent protection. Otherwise, an optional acid-free barrier can be placed between mount-board and backboard, providing additional protection against environmental contamination. Some framers suggest using a sheet of inert plastic or glass as a barrier, but I am concerned that they create a potential humidity trap and recommend using an acid-free paper barrier instead.

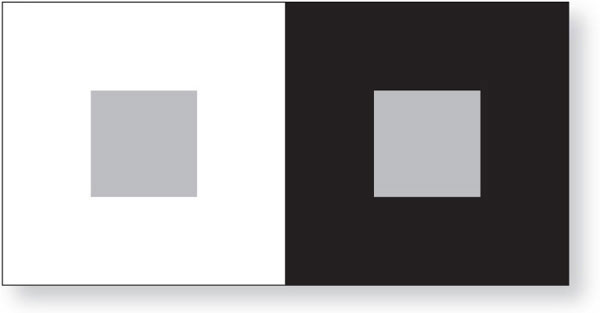

fig.5 Our subjective sensation of reflection density is noticeably influenced by the surroundings of the evaluated sample. A medium gray appears to be darker in the vicinity of white than when surrounded by black.

Sheet Size and Thickness

Many suppliers offer boards in either standard or custom sizes. The standard sizes are often too restrictive, and the custom sizes are quite expensive. If you have available storage space and the proper equipment, it is more flexible and more economical to purchase the boards in ‘full’ sheets and cut them to size yourself. Full sheets come in a variety of sheet sizes, with 32 × 40 inches being the most common dimensions, and it is advisable to prepare a cutting plan (see fig.4) to minimize waste. Nonetheless, do not turn prudence into false economy. Select a mount-board size that suits the image, your style and the intended presentation, not the one that gives you the least amount of scrap. Conveniently cutting four 16x20-inch sheets from one 32x40-inch board may illustrate efficient planning but little aesthetic consideration. No one will see your cut-offs, but many will notice an inappropriate mount size. I keep my cut-offs to create useful tools, jigs and spacers for studio and darkroom work.

Mounting and matting board comes in thicknesses of 2, 4, 6 and 8 ply, with 4 ply, which is equivalent to 1/16 inch or 1.5 mm, being the most popular. Galleries and museums often use the thicker boards for large mounts or special effect. Backing board is thicker and varies from 1/8 to 1/2 inch, but not all sizes are available in museum quality. Consider also, before you order expensive thick boards, whether your mat cutter can actually cut that thickness. For example, few cutters can handle bevel-cuts in 8-ply boards.

fig.6 It is commonly agreed that a print, centered on the vertical axis, appears to be too low on the mount. This print placement creates an optical illusion that the print is not equally spaced at top and bottom; the print seems to sag below the vertical center (a). To overcome this illusion, alternative print-placement techniques must be considered (b).

Color

Selecting an appropriate color for the mounting materials seems largely to be a matter of personal taste and preference. Nevertheless, a few facts should be considered before making a final color choice. As already stated, the mount needs to complement the print without becoming a distraction. As a general rule, this disqualifies the use of colored mounts for B&W prints. There may be the odd exception to this rule to support an intended mood, as I have seen in an exhibition of reenacted Civil War images, where prints were sepia toned and suitably displayed on a light tan mount to imply age. However, most B&W prints are presented on either white or black mount-board, and there have been heated debates as to which is the better of the two options.

Our subjective sensation of reflection density is noticeably influenced by the surroundings of the evaluated sample. The medium gray in fig.5 appears to be darker in the vicinity of white than when surrounded by black. In fact, all print tones are sensed to be darker on a white mount than they are perceived on a black mount. Consequently, a black mount brings maximum brightness to the highlights but fails to show the full potential of deep shadows. On the other hand, a white mount allows for rich shadows but at the risk of foggy highlights. Neither black nor white seem to be the optimum color choices for skilled B&W print mounting.

As we will see in ‘Fine-Tuning Print Exposure and Contrast’, the human eye is far more sensitive in detecting reflection density differences in highlights compared to shadows. This presents an obvious solution. Choosing mounting board slightly darker than paper-white creates enough variance for the highlights to be seen as true whites while this tonality change is too minute to detectably degrade the shadows. Selecting even off-white mounting board will improve highlight appearance over the use of bright-white mounts and mats. Although I discourage using black mounting board, I admit that it lifts the highlights of a print, when displayed in dimly lit surroundings, and improves the appearance of poorly printed images containing veiled highlights.

Mount Size

Assuming a border-mount style, the question of how wide the print-surrounding mount borders and, consequently, how large the whole mount-board should be, needs to be answered. The print mount and frame separates the image from the rest of the wall, adjacent images and the room, allowing the eyes to concentrate exclusively on the image. The dimensions for the mount are mainly a subjective consideration and an indication of the photographer’s style or an exhibition’s theme. The mount size, nevertheless, also must be a reflection of what is exhibited where.

I prefer some ‘breathing space’ around the print. Large mount borders seem to raise the visual importance of a print. Small borders offer a more economical look. Really hefty mount borders can look pretentious, but depending on the situation, it sometimes works well. A single 5x7-inch print mounted on an 18x22-inch board inarguably demands a certain level of respect and conveys preciousness. Large exhibition spaces with high ceilings also tend to suit larger mounts, even if the images are small. Brightly colored walls need larger mounts to separate the photograph from that potentially disturbing influence. Images that are not related to those hanging next to them require a substantial mount to convey separation. If the exhibition context is unknown at the time an image is mounted, you are less likely to go wrong with a good-sized mount. As a rough guide, consider a 3-inch mount border as a minimum and 4 inches as standard, but do not hesitate to claim 6 inches or more, if it suits the print and its presentation.

fig.7 To find a pleasing print placement, locate the ‘optical center’ (a), and place the print at that location (b). If this results in the print being too high or too low on the mount, slide it up or down until you reach a more attractive distribution of space, but always maintain a minimum, vertical print offset (c).

Print Orientation and Placement

Since it is one of the most important functions of the mount to visually isolate the print, optimum print orientation and placement consists of properly apportioning the space around the print. Most photographers, unless specializing in landscapes, produce the majority of their images in a vertical print composition. Generally, the presentation mirrors the print: vertical presentation for vertical prints and horizontal presentation for horizontal prints. Horizontal prints, however, can also be successfully mounted on vertical mount-boards, especially when exhibited within a panel, dominated by vertical prints on vertical mounts. Square prints call for a vertical mount-board orientation more often than not.

Unless you are aiming for a very special effect, there is little argument against placing the print centered on the horizontal axis of the mount. However, attractive print placement on the vertical axis requires a closer look into optimum print isolation and subjective preferences.

It is commonly agreed, and obvious even to the most untrained observer, that a print centered on the vertical axis appears to be too low on the mount. This print placement creates an unfortunate optical illusion that the print is not equally spaced at top and bottom (see fig.6a). In other words, the print seems to sag below the vertical center. To overcome this illusion, alternative print-placement techniques must be considered (see fig.6b).

One accepted technique involves placing the print near the ‘optical center’ of the mount (fig.7a-b). This makes for an attractive print placement in most situations. To find this optical center, align the upper left-hand corners of the print and mount-board in point ‘A’. Now, bisect the remaining spaces to the bottom and right of the print, creating lines ‘a’ and ‘b’, respectively. Then, connect point ‘B’ and ‘0’, creating line ‘c’, which intersects line ‘b’ in point ‘1’ (fig.7a). Finally, align the lower right-hand corner of the print (point ‘C’) with point ‘1’ on the mount-board (fig.7b). The print is now at the optical center of the mount.

This technique is only a good starting point, and not an automatic substitute for accomplished design or personal preferences. If placing the print at the optical center results in an unattractive, narrow border on top or bottom of the print, additional vertical adjustments have to be made. While making these adjustments, the bottom of the print must never lie below line ‘d’, or the print is in danger of suffering the illusion of sag (see fig.7c). Line ‘d’ reflects your individual, minimum, vertical print offset. Its location depends on your personal preference and style, but I suggest keeping line ‘d’ at least 10% above line ‘a’.

Let us summarize the method of finding an optically pleasing print placement. Locate the optical center (see fig.7a), and place the print at that location (see fig.7b). If this results in the print being too high or too low on the mount, slide it up or down until you reach a more attractive distribution of space, while always maintaining a minimum, vertical print offset (see fig.7c). In most cases, optimum print placement is achieved when the print is horizontally centered and its bottom edge is vertically located between points ‘1’ and ‘2’.

Mounting Tools and Recommended Practices

In addition to a clean, comfortable and well-illuminated work space, you need a few special tools and utensils to mount and mat your prints effectively. The most expensive item by far is a dry-mount press (fig.8). It holds mount-board, dry-mount tissue and print in place under pressure, while melting the tissue to form a permanent bond. With a bit of luck, a dry-mount press can be found secondhand, and they usually last a long time, before they might need a heating element or a thermostat replaced. You also need a good mat cutter, which ought to be large enough to cut 32x40-inch sheets in width (fig.9). Make certain that it can cut bevels into 8-ply boards and at least 1/4 inch (6 mm) thick backing board to size.

Continuing down the list of specialty items, we come to the tacking iron (fig.10). This is a miniature iron, obtainable from your mounting supplier, or often for less money, in hobby and craft stores. I prefer the adjustable type with the smooth Teflon finish. They do not get hot enough to melt the dry-mount tissue thoroughly, but they heat it just enough to tack it to the backside of the print and to the mount-board, keeping everything together and in place until the final bond is completed in the dry-mount press. In order for the dry-mount tissue to stick to the print and mount-board, but not the tacking iron, you need a sheet of release paper. This paper has a silicon coating on one side, which inhibits the adhesive from bonding to it. Your mounting supplier sells release paper by the roll, but the backing sheets of printer labels work adequately as a substitute. The last special mounting tool required is a simple burnishing bone (see fig.15f). It is used to give the bevel cuts in the overmat a final touch. They are also available from your mounting supplier.

fig.8 The most expensive mounting tool is a dry-mount press. It holds mount-board, dry-mount tissue and print in place under pressure, while melting the tissue to form a permanent bond.

fig.9 A good mat cutter is large enough to cut 32x40-inch sheets in width. It can also cut bevels into 8-ply boards and 1/4 inch thick backing board to size.

fig.10 A tacking iron is used to keep print, dry-mount tissue and mount-board temporarily aligned, until the final bond is made in the dry-mount press.

The remaining utensils required are minor items, and you probably have some of them already. They include a short and a long stainless-steel ruler to take a few measurements and to have a solid cutting guide; a soft brush to frequently dust things off; a couple of drafting weights to serve as an extra pair of hands; a small but sharp knife with replaceable blades to trim the print and dry-mount tissue precisely; lint-free gloves to avoid fingerprints on the print; a hard and a medium soft pencil to mark dimensions and to sign the artwork; and a calculator and a soft eraser to avoid and correct mistakes.

Physical print placement, with only the aid of a ruler, is certainly possible, but it can be tricky and cumbersome. It often necessitates many, continually decreasing adjustments until the print is precisely in the preferred location on the mount-board. If you plan to mount prints regularly, consider the acquisition of a mounting jig. There are different models available for purchase, but I made mine from a spare baseboard of my, now wall-mounted, enlarger (fig.11). It makes the horizontal alignment of mount-board and print centers effortless and keeps the print horizontal, while trying to find the best vertical location.

Finally, you need a large and rigid surface, free of obstacles, on which to work. For this purpose, I made myself a 3x8-foot table from birch wood. It has a comfortable working height and shelves to store supplies (fig.12). To protect the table-top from cuts, I use a 2x3-foot self-healing cutting-mat (obtainable from craft or fabric stores), or if more space is necessary, I just use a fresh piece of mounting board. The table is large and rigid enough to accommodate the long mat cutter (on the left) and to carry the heavy dry-mount press (on the right).

Another prerequisite for successful mounting is cleanliness. Fingerprints on fine photographs are totally unacceptable, but fortunately, they are also completely avoidable. For that reason, I strongly recommend always wearing lint-free gloves whenever handling, mounting, matting or framing prints.

Unfortunately, there are other gremlins, trying to spoil our print presentation. Always guard against small particles, coming from framing debris, paper trimmings, fabric fibers, hair or dust, just to name a few. If they get under dry-mount tissue or print, they are likely to show through the print surface and create an objectionable ‘pimple’. If such particle finds its way between the print surface and the upper plate, or the insertion board, of the dry-mount press, it may leave a visible imprint and unsightly ‘dimple’ on the print. Pimples are impossible to remove and ruin the already mounted print. Dimples cannot be completely removed, but first swelling the emulsion with a tiny drop of distilled water or alcohol, and then leaving it to dry, can reduce the indentation. Even so, dimples still cause unnecessary labor and needless frustration.

fig.11 If you plan to mount prints regularly, consider the acquisition of a mounting jig. Different models are available for purchase, or one can be made from a spare enlarger baseboard.

Always have the soft brush handy to frequently dust off all mounting and supporting surfaces to bring an end to pimples. For example, when preparing a print for dry-mounting, put it down, faceup onto a clean piece of mounting board, and dust off the image side. Then, pick the print up, dust off the mounting board and place the print facedown. Now, dust off the backside of the print, before applying the same procedure to the dry-mount tissue. This is an elaborate process, but it is the only way to steer clear of pimples. Occasionally, clean the upper plate of the dry-mount press, or replace the insertion board to prevent dimples, and never forget to wear the gloves.

fig.12 A self-made table offers a large and rigid surface to work at a comfortable height, while providing extra shelves to store supplies.

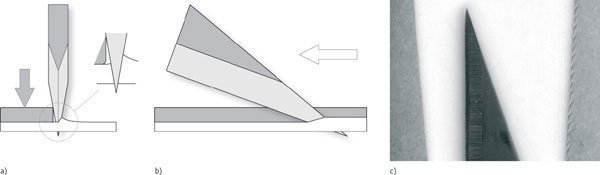

fig.13 During cutting, the wedge-shaped blade forces its way through the paper under a certain angle, pushing the upper paper fibers further aside than the lower fibers (a-b). This different displacement of interwoven fibers causes them to bulge, and occasionally rip, at the paper surface, unless fiber movement is somehow restricted. By sliding the cutting blade alongside a steel ruler, and pushing this ruler firmly down onto the paper during cutting, one side of the paper is constrained, while the other remains free to move. As a result, the side sandwiched between ruler and cutting-mat will have a reasonably smooth and clean edge, whereas the other side will be rough and jagged-looking (c).

Using exclusively fresh, truly sharp, cutting blades is another requirement to avoid disappointment. Trying to squeeze the last bit of performance out of a blade is definitely false economy. The sensitive cotton fibers of museum board, for example, demand the sharpest blades possible to guarantee a smooth and clean cut. If the blade is even remotely dull, it will rip the fine fibers more than cut them. For simply cutting boards to size, this might be tolerable up to a point. However, for delicate and forever-visible bevels of an overmat, anything less than a flawlessly clean cut is completely unacceptable. A less than perfect overmat must be discarded and replaced, before it gets a chance to spoil the entire print presentation and ruin the photographer’s reputation. At today’s material prices, the replacement cost for a new overmat is roughly equivalent to the cost of thirty new blades. A timely blade replacement proves to be a worthwhile investment!

When trimming prints, the cleanest cut is attained using a steel straight-edge or ruler, and a scalpel with a fresh, very sharp blade. However, handle these tools with extreme care. A sharp scalpel respects the toughness of steel as a guide, but it does not differentiate between paper and fingers. I strongly suggest using a ruler with a finger guard. Always keep the ruler on the print and not on the cut-offs. It is inherent to the cutting process that the material is divided, but unlike sawing, no material is lost or removed; it is just displaced. However, the displacement is not consistent. As the wedge-shaped blade forces its way through the paper under a certain angle, it always pushes the upper paper fibers further aside than the lower fibers (fig.13a-b). This different displacement of interwoven fibers causes them to bulge, and occasionally rip, at the paper surface, unless fiber movement is somehow restricted. By sliding the cutting blade alongside a steel ruler, and pushing this ruler firmly down onto the paper during cutting, one side of the paper is constrained, while the other remains free to move. As a result, the side sandwiched between ruler and cutting-mat will have a reasonably smooth and clean edge, whereas the other side will be rough and jagged-looking (fig.13c). Consequently, it makes for cleaner print edges to always trim print and dry-mount tissue with the ruler placed on the print and not on the cut-offs. Be sure that the steel ruler has no sharp edges or burrs, which could scratch the sensitive print surface.

Mounting and Matting (Step by Step)

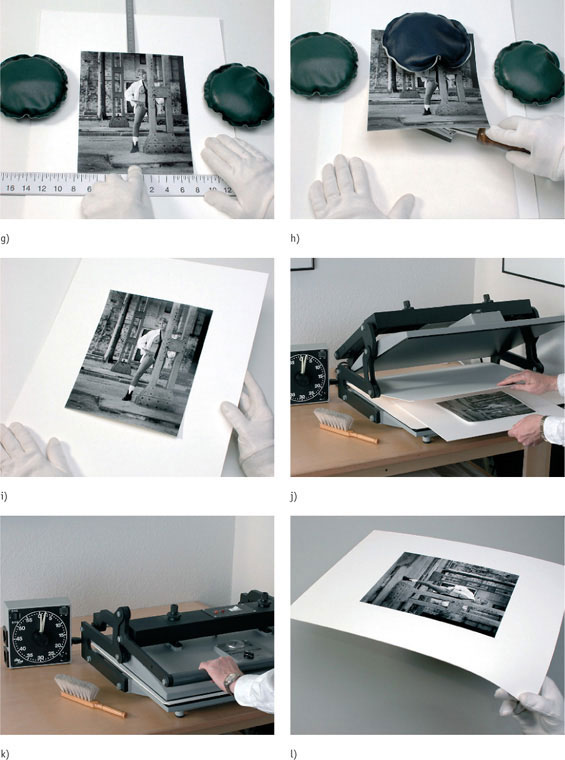

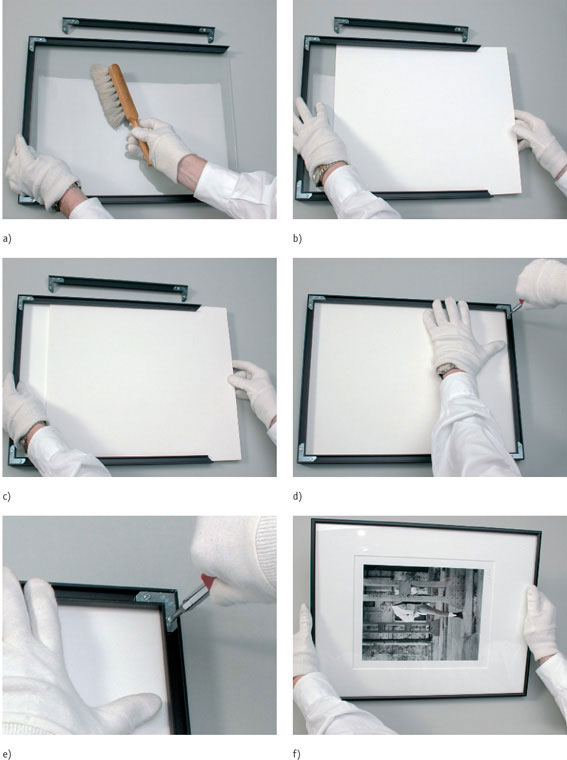

Dry-Mounting

Start by preparing a clean and well-lit work area, and get all tools and materials ready to go. Turn-on the tacking iron and the dry-mount press, select the appropriate temperature for the dry-mount tissue used, and leave them to warm up. Meanwhile, cut a mount-board, matting-board and a backboard to size, and put them aside for now. Do the same for the dry-mount tissue, unless you have the pre-cut sheets (see fig.14a). The tissue dimensions should be slightly larger than the untrimmed print (1.5 mm or 1/16 inch, on each side), to make double sure that the adhesive will reach the entire print periphery, even if it is slightly misaligned in the next step.

Cover the work surface with some spare, but clean, mounting board to have a smooth surface to work on. Dust-off work surface, print and dry-mount tissue well. Put the print facedown, cover it with the dry-mount tissue, and place a piece of release paper on top. Use one hand or a drafting weight to hold it all in place, and press the heated tacking iron onto the release paper (see fig.14b). Make certain that the flat surface of the iron rests evenly on the paper. Without pressing it down too hard, and while keeping the tacking iron in small circular motion, apply the heat for about 20 seconds, until the dry-mount tissue sticks to the print. Repeat in a second location, but stay on the same half of the print. We need the other half to be unattached, when we tack it to the mount-board later.

Turn the print and dry-mount tissue carefully around, and trim the edges, as appropriate for the print composition (see fig.14c). I suggest trimming off at least a millimeter or two, regardless of any artistic considerations. This way, all residual chemicals, which penetrated the print edges and were not washed out completely during print processing, are removed. After trimming, print and dry-mount tissue are precisely the same dimensions and are perfectly aligned to each other (see fig.14d).

Take the two pieces of already sized mount-board and critically inspect them front and back. Mounting board often has unavoidable minor flaws or imperfections. As tiny as some of them are, they will certainly catch the observer’s eye and create unwanted distractions. It is almost impossible to remove these flaws from the fibers, without leaving obvious telltale signs of repair work. It is far easier to leave them alone, but relegate minor imperfections to the back of the boards. If you find them on both sides of a board, hiding them becomes more difficult, although you may still have the opportunity to successfully conceal them with the print or the overmat, or better yet, you may be fortunate enough to lose them to the window cut-out of the overmat. Inspecting both boards prior to use will also help you decide which of the two pieces is more appropriately used as a mount-board and which as an overmat. Nevertheless, every once in a while, it seems impossible to lose or hide all board flaws. In that case, replace it with a fresh piece, and save the rejected board for a future application, hoping for the next print or overmat to cover or lose all imperfections.

Select which board is to be used as the mount-board, and save the other as the mat-board. Depending on the storage conditions of the mounting board used, you may elect to slip the mount-board into the dry-mount press for two minutes to dry it out before mounting the print. High initial moisture content of the mount-board can cause adhesion problems with the dry-mount tissue or may cause the board to bend or warp after bonding. Leave the board, for two more minutes, to dry and cool down.

Take the dried mount-board and select the most suitable mount orientation, considering print orientation and presentation style. Use two drafting weights, as an extra pair of hands, to keep the mount-board from moving around (see fig.14e). Then, use a jig, or a small ruler, to determine the optimum print placement on the board. The print should be centered left to right, and the bottom border should be larger than the top (see fig.14f-g). Start with the optical center, and work your way up or down from there, if needed.

Set another drafting weight on the print to secure its location, but be sure to put it on the side that is already attached to the dry-mount tissue. On the other side, slip the release paper between the print and the tissue. Now, place the tacking iron below the print but on top of the release paper, and tack the dry-mount tissue to the mount-board at one or, better, two places (see fig.14h). Remove the release paper. The print and the dry-mount tissue are now attached to the mount-board at the desired location, while still perfectly aligned to each other (see fig.14i), but the bond is still weak. Handle the assembly carefully, and do not hold it upright or the print might tear off.

It is important to choose an appropriate dry-mount operating temperature. If the temperature is too low, the bond is weak, and the print will delaminate at the corners and edges. If the temperature is too high, the print will get damaged, or if high enough, the adhesive will form bubbles and ruin the mount. The actual press temperature can be tested with a small thermometer, fitted into the press between two sheets of mounting board. FB prints can be exposed to fairly high operating temperatures (up to 225°F or 105°C). RC prints require lower temperatures (not more than 200°F or 95°C), otherwise the plastic layers on the paper will melt and ruin the print. Therefore, RC papers call for special dry-mount tissue, which melts at a lower temperature than the plastic on the paper does. I prefer porous dry-mount tissue with a low minimum operating temperature (175°F or 80°C), which is, consequently, suitable for both FB and RC prints, as well as other sensitive materials.

fig.14 a) Cover the work surface with some spare mounting board, to have a smooth surface to work on. Get the print and dry-mount tissue, and dust-off everything well.

b) Put the print facedown, cover it with the dry-mount tissue, and place the release paper on top. Put the heated tacking iron down flat, so it rests evenly on the paper. Apply the heat for about 20 seconds, until the dry-mount tissue sticks to the print. Repeat in a second location.

c) Turn the print and dry-mount tissue around, and trim the edges, as appropriate for the print composition, but trim off at least a millimeter. This way, all residual chemicals, which were not washed out completely during print processing, are removed.

d) After trimming, print and dry-mount tissue are precisely the same dimensions and are perfectly aligned to each other.

e) Take the mount-board and select the most suitable mount orientation to present the image. Generally, the presentation mirrors the print: vertical presentation for vertical prints and horizontal presentation for horizontal prints.

f) Use drafting weights as an extra pair of hands to keep the mount-board from moving around. Then, use a jig, or a small ruler, to determine the optimum print placement on the board.

fig.14 g) The print should be centered left to right, and the bottom border should be larger than the top, while not letting the top border to become smaller than the sides.

h) Set a drafting weight on the print to secure its location, and slip the release paper between the print and the tissue. Now, place the tacking iron below the print but on top of the release paper, and tack the dry-mount tissue to the mount-board.

i) Remove the release paper. The print and the dry-mount tissue are now attached to the mount-board at the desired location, while still perfectly aligned to each other, but the bond is still weak. Handle the assembly carefully, and do not hold it upright or the print might tear off.

j) Insert the print assembly between two sheets of clean mounting board and close the dry-mount press.

k) Keep the press closed for up to two minutes for RC prints and up to three minutes for FB prints, but follow manufacturer’s instructions for operating temperatures and times.

l) Take the mounted print from the press, and place it under glass for five to ten minutes. After it has completely cooled, check the print adhesion, by holding the mount-board at each edge without permanently bending it. Inspect all print corners to make sure that print and tissue are not delaminating from the mount-board.

Heat distribution in the dry-mount press must be even, without hot spots. I have two sheets of mounting board in my dry-mount press. The top sheet distributes the heat from the upper plate more evenly and reduces dimpling of the print surface. The bottom sheet keeps the lower foam pad clean. Insert the print assembly between the two sheets and close the dry-mount press (see fig.14j-k). Keep it closed for up to two minutes for RC prints and up to three minutes for FB prints, but follow the instructions of the dry-mount press and tissue manufacturer for appropriate operating temperatures and times.

Take the print from the dry-mount press, and quickly place it under a thick sheet of glass for five to ten minutes, which allows the molten adhesive to cool and solidify, without curling the print or warping the mount-board. Some printers recommend the use of an aluminum sheet instead, for improved heat dissipation, but for me glass works fine, is perfectly flat and inexpensive. After the print has completely cooled, you might want to check the print adhesion. To do so, hold the mount-board at each edge (see fig.14l) without permanently bending it. Inspect all print corners to make sure that print and tissue are not delaminating from each other or from the mount-board. If they are, simply return them to the press for more time, possibly at a slightly higher temperature.

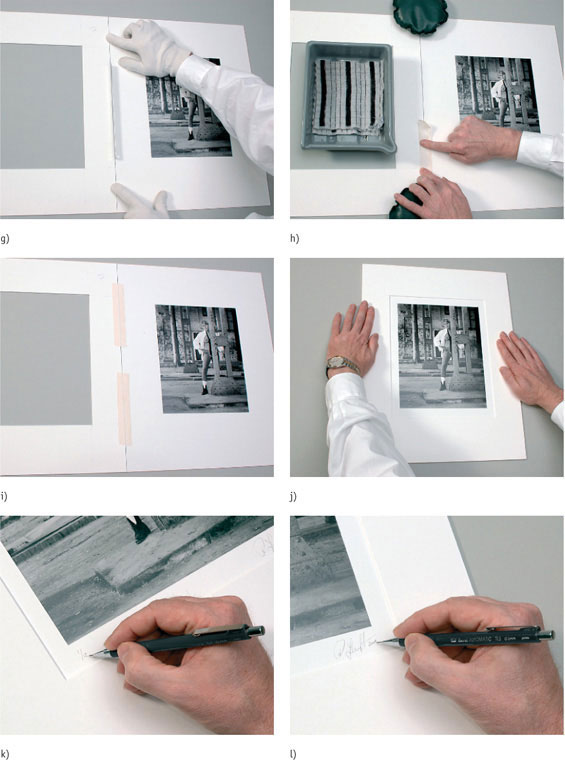

Matting

The only difference when cutting an overmat for a dry-mounted print or a corner-mounted print is the size of the window opening. When matting a dry-mounted print, as illustrated in fig.15, the window opening may be large enough to expose the entire print and some of the mount-board around it. The window opening for a corner-mounted print, however, needs to be small enough to secure and cover the print periphery.

Get the mat-board and inspect it for imperfections again, making sure that any imperfections either are on the backside or will be removed with the window opening. It is easier to mark the window cutting if a relatively large work surface is available, so the mount and mat-board may be positioned next to each other.

Put mount and mat-board down so that the print and the backside of the mat-board are facing you. With the help of a ruler, measure the distance from the print border to the edge of the mount-board on all four sides. Deduct 5/8 inch (15 mm) from the left, top and right measurements to derive the desired dimensions for the overmat window (see fig.15a). Draw soft, thin lines from edge to edge onto the mat-board at the respective locations (see fig.15b). Do the same for the bottom of the mat-board, but deduct 3/4 to 1 inch (20 to 25 mm) to gain more room below the print. You will need this extra space to identify the mounted print with your signature and an edition number. Mark the top-right corner of the mat-board as ‘top-left’ (see fig.15c). Remember, the mat-board is still lying facedown, so ‘left’ and ‘right’ are opposite! This will help to identify and maintain the correct mat-board orientation on the mount-board after cutting the window opening.

Refer to the instructions that came with your mat cutter for the correct procedure on how to cut the window opening into the mat-board, as this depends somewhat on your specific equipment (see fig.15d). However, some advice for efficient use of a bevel-cutter seems universal. Cut the short edges first, so the remaining edges give maximum support to the window cut-off. Over-cut all edges by about one or two millimeters, ensuring that the corners are cut all the way through. A window cut-off hanging from one corner can rip the fibers and ruin the entire mat-board. The cuts along all four edges must completely separate the window cut-off from the overmat.

Matching the ‘top-left’ marking on the backside of the overmat to the print’s top-left, place the overmat on the mount-board and verify that the window opening has been cut correctly (see fig.15e). The freshly cut bevels always have a slight burr on the show-surface of the overmat, no matter how sharp the blade is. Use the burnishing bone to smooth all four edges and the corners of the bevel (see fig.15f). To do this, run the bone across the bevels, with only light pressure applied. Using one of the bone’s edges, get deep into the bevel corners, and use the bone tip to smooth out the bevel over-cuts on the show-surface. A burnishing bone improves bevel appearance significantly.

Place mount-board and overmat next to each other, like two facing pages of an opened book, with the overmat still lying face-down. With the aid of a thin steel ruler, wedged between the two boards, create a thin, consistent gap between the two boards to provide room for a taped hinge (see fig.15g). Secure the position of the boards with two drafting weights. At a safe distance from the mounting area, get a clean, dripping-wet washcloth, fold it and put it into a 5x7-inch processing tray, large plate or dish. The set-up shown in fig.15h is purely for illustration purposes. I cannot recommend allowing water so close to your artwork, since it creates a significant risk of getting spills or drips onto the print.

Cut two pieces of the gummed, acid-free cloth tape of generous length. Four to six inches (100 to 150 mm) is about right. These will be used to create the hinge between mount-board and overmat. Take one of the two pieces of tape, thoroughly wet the gummed adhesive by pressing the tape onto the washcloth, and gently press the tape onto one half of the boards, trying to get the tape evenly onto both boards (see fig.15h). Repeat on the other half of the boards with the second piece of tape, and remove the drafting weights (see fig.15j). Before the water-soluble adhesive has a chance to dry, making slight adjustments impossible, close the assembly, and make sure the overmat and the mount-board are aligned correctly. If not, there is still time to tweak the arrangement (see fig.15j). After you are completely satisfied with the alignment, use the drafting weights again to keep everything in place for a minute or two, while the adhesive dries.

To finish dry-mounting and matting a print, make the artwork identifiable by adding an edition number on the left (see fig.15k), and by signing and dating the mount-board on the right (see fig.15l), just below the print. The dry-mounted and matted print is now presentable and ready for framing.

Corner-Mounting

Fig.16 illustrates corner-mounting, which is an alternative to dry-mounting. Both processes utilize the same tools and materials with the exception that a corner-mounted print is held, as the name implies, at the corners by plastic or paper pockets. The corner pockets can be purchased or self-made from acid-free paper. Since most purchased pockets, made of plastic (polypropylene), are backed with a self-adhesive of unknown origin, I prefer to make the corners myself from acid-free cotton paper.

Cut a 1x2-inch (25x50-mm) piece of acid-free paper, and fold it from the center of one of the long sides to both opposite corners, creating one large and two small triangles (see fig.16a, step 1-4). Unfold the paper, and ‘hollow’ out the large triangle, leaving only a small border of about 1/8 inch (see fig.16a, step 5-6). After turning the paper around, the newly made paper pocket is slipped over the print corner (see fig.16b).

Make a pocket for each corner, slip them over the print, place the print on the mount-board and secure it with a drafting weight (see fig.16c). Cut an overmat, with a window opening small enough that the corner pockets and the print borders are hidden. Place the overmat on top of the print, and check the window opening for size (see fig.16d). Hinge-mount the overmat, and adjust final print alignment if necessary (see fig.16e). Finally, cut four pieces of 2-inch (50 mm) long, gummed, acid-free paper or cloth tape, and firmly press the tape onto the corner pockets, avoiding contact between the tape and the print (see fig.16f).

The print is now corner-mounted and ready for framing. Do not expect the print to be as flat as its dry-mounted counterpart would be. This is a tradeoff for the flexibility of being able to remove the print from its mount with ease.

Print Identification

The final touch to a competently mounted and matted print is the full identification and personalization of the artwork. This not only provides future observers and prospective buyers with providence of the print, but it also increases the print’s potential value as a collector’s item and demonstrates the artist’s full commitment to the work accomplished. To follow the guidelines of not distracting from the image itself, print identification must be clear, but modest.

I prefer to have the print edition number, the date and my signature (but not the image title) readily available while looking at the image. Therefore, this information is entered just below the print onto the mount-board, where it is still exposed by the window in the overmat (see fig.15k-l). I use a medium soft and almost dull pencil, making clearly legible but delicate entries. A freshly sharpened or hard pencil will mar the surface and disrupts the smooth flow of writing. A pencil too soft, on the other hand, will make the writing far too dominant, demanding more attention than this secondary information deserves.

fig.15 a) Put mount and mat-board down so that the print and the backside of the mat-board are facing you. Measure the print borders and deduct the desired clearances to derive the dimensions for the overmat window. Leave more room below the print to have some extra space for signature and edition number.

b) Draw thin lines onto the mat-board at the respective locations.

c) Mark the top-right corner of the mat-board as ‘top-left’. Remember, the mat-board is still lying facedown! This will help to identify and maintain its correct orientation on the mount-board after cutting the window opening.

d) Refer to the instructions that came with your mat cutter, for the correct procedure on how to cut the window opening into the mat-board.

e) Matching the ‘top-left’ marking on the backside of the overmat to the print’s top-left, place the overmat on the mount-board and verify that the window opening has been cut correctly.

f) Use the burnishing bone to smooth all four edges and the corners of the bevel. Using one of the bone’s edges, get deep into the bevel corners, and use the bone tip to smooth out the bevel over-cuts on the show-surface.

fig.15 g) Place mount-board and overmat next to each other, with the overmat still lying facedown. With the aid of a thin steel ruler, wedged between the two boards, create a consistent gap between the two boards.

h) Secure the position of the boards with two drafting weights. Cut two pieces of gummed tape, four to six inches in length. Take one, wet the adhesive, and gently press the tape onto one half of the boards, trying to get the tape evenly onto both boards.

i) Repeat on the other half of the boards with the second piece of tape, and remove the drafting weights.

j) Before the adhesive has a change to dry, close the assembly, and make sure the overmat and the mount-board are aligned correctly. If not, there is still time to tweak the arrangement. Again, use the drafting weights to keep the boards aligned, and let the adhesive dry.

k) To finish dry-mounting and matting a print, make the artwork identifiable by adding an edition number below the print on the left.

l) Then, sign and date the mount-board on the right.

The mounted and matted print is now presentable and ready for framing.

fig.16 a) Cut a 1x2-inch piece of paper, and fold it from the center of one of the long sides to both opposite corners, creating one large and two small triangles (step 1-4). Unfold the paper, and ‘hollow’ out the large triangle, leaving only a small border of about 1/8 inch (step 5-6).

b) Slip the newly made paper pocket over the print corner.

c) Make a pocket for each corner, slip them over the print, place the print on the mount-board and secure it with a drafting weight.

d) Cut an overmat, with a window opening small enough that the corner pockets and the print borders are hidden. Place the overmat on top of the print, and check the window opening for size.

e) Hinge-mount the over-mat, and adjust final print alignment if necessary.

f) Cut four pieces of 2-inch long, gummed tape. Firmly press the tape onto the corner pockets, avoiding contact between the tape and the print.

The print is now corner-mounted and ready for framing.

It is clearly up to the artist whether to prepare limited-edition prints or to make an unlimited amount of copies. In the past, I limited my fine-art print editions to twelve copies of any size, after which I made no further prints from that negative. Other typical edition limits are 50, 100, or optimistic photographers may choose 250, 500 or even more. If you are uncomfortable with the potential confinement and the inherent commitment of limited editions, there are alternatives. First, you can just number your prints, starting with ‘#1’, instead of ‘1/250’, or you can prepare print editions like the publishing industry does for books. You will see more on this in the chapter ‘What Size is the Edition’.

Next to the signature, in very small print, I routinely add the year the image was taken. Dating the image is often considered necessary to create a meaningful association with a certain era or period, thereby putting the visual information into perspective and making the print more consequential.

Any additional information may be helpful but does not belong on the presentation side of the mounted print. A custom-made rubber stamp (fig.17), which contains the photographer’s full name, a copyright and quality statement, room for the date the image was taken and the print was made, as well as space for the print number and the edition, is a good way to record additional information. Stamp the backside of the mount-board and the backboard with acid-free ink, and complete the missing information using an acid-free pen (not a pencil) on both. Now, add the image title somewhere near the stamp.

I keep the image title on the back, rather than on the front of the print. An observer’s interpretation of an image is always filtered by personal experiences and current emotions. Therefore, an image is likely to provoke different responses in different people. By presenting the image title on the print, these individual responses are muted, because this title reflects the photographer’s image intent and is influenced by the photographer’s experiences and emotions. An untitled image is far more likely to provoke a genuine emotion and response in the viewer.

fig.17 A custom-made rubber stamp, which contains the photographer’s full name, a copyright and quality statement, room for the date the image was taken and the print was made, as well as space for the print number and the edition, is a good way to record additional information. Stamp the backside of the mount-board and the backboard, and complete the missing information using an acid-free pen.

fig.17a This is my old rubber stamp for when I limited my fine-art print editions to twelve copies of any size, after which I made no further prints from that negative.

fig.17b This is my new rubber stamp, after switching from ‘limited printing’ to ‘true editioning’. During each printing session, I usually make 1-4 prints. If I reprint on another day, it’s the next printing session. If I change the printing style for the image, it’s a new edition. This allows for an unlimited number of prints and still defines each print precisely for collectors and galleries.

Print Spotting

Closing in on perfection with a bit of cleanliness

Few freshly made prints are completely free of visual defects. Unavoidable dust and tiny scratches on the negative, plus the occasional emulsion damage and fingerprint, create unwanted spots, lines and other blemishes on the print. These imperfections must be concealed, because they spoil a clean presentation and distract from the image. Print spotting is the process in which unwanted spots are disguised by adjusting their tonality to match the surrounding tones.

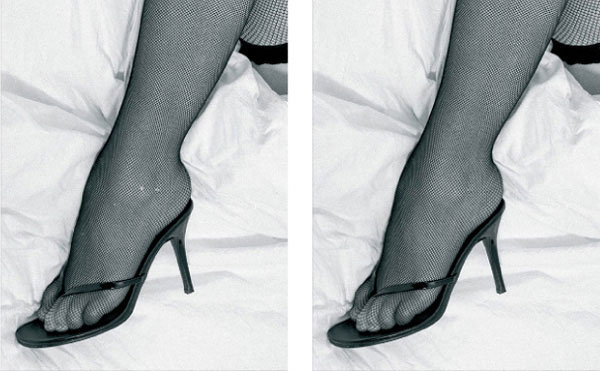

fig.1 There is usually a remarkable difference between unspotted and carefully spotted prints, especially when considering how minute the alterations often are. Print spotting removes disturbing visual defects, which disturb the print enjoyment and lessen its visual impact.

Print spotting is not just cosmetic. Its main function is to remove disturbing visual noise, which gets in the way of print enjoyment and lessens its impact. There usually is a remarkable difference between un-spotted and carefully spotted prints, especially when considering how small the alterations often are (fig.1). This makes spotting a highly effective and rewarding task, but it can also be a labor-intensive, time-consuming and sometimes frustrating task, particularly when it does not work as well as we had hoped. As always, prevention is better than repair, and consequently, it is best to eliminate the need for spotting as much as possible. The less spotting your prints require, the better off you are. The root cause for print blemishes is dirt and dust. To minimize the need for spotting, keep your negatives clean and handle them with care to prevent scratches. Make sure your entire camera equipment and darkroom are as tidy and dust-free as possible. Remove dust from work surfaces, cameras and film holders on a regular basis. Gently remove all loose dust from the negative and the enlarger’s negative holder with compressed air or an anti-static brush before printing them. Carelessly stored, ill-treated or much-printed negatives may benefit from a gentle wash prior to using them again.

White Spots and Black Spots

There are two types of print imperfections that require spotting, white spots and black spots. Most blemishes are much lighter than their surroundings. Most are caused by small dust particles stuck to the negative or to the glass of the negative carrier. They are highly distracting but easy to remove. Others are telltale signs of small fibers and hair, leaving thin, bright trails on the print. They need a bit more patience and practice to disguise. Dark spots are typically caused by dust on the film during in-camera exposure or by damage to the negative emulsion. Some literature recommends etching the print surface to remove blemishes that are darker than their surroundings. However, etching requires scratching and irrevocably damaging the print’s surface. I will demonstrate how this is completely avoidable when print spotting is combined with other retouching techniques.

Spotting Equipment and Materials

Print spotting is accomplished by using a small brush and repeatedly applying a darker dye to a lighter spot, line or blemish, until its shade closely matches the surrounding tones and blends into the rest of the print. The goal is not to eliminate the imperfection altogether, but to move it from attention-grabbing boldness to inconspicuous obscurity.

The ideal work area for spotting is dry, uncluttered and dust-free. It also provides bright and even lighting, has a good-size sturdy table and comfortable seating. Typical spotting tools include a large magnifying glass or extra-strong reading glasses, a set of very small, fine-tip, high-quality brushes, a pair of clean, lint-free nylon or cotton gloves, some blotting paper or a paper towel, a few spare pieces of mount-board and a saucer or porcelain palette to mix and dilute the spotting dye (fig.2). Make sure to also have a cup of distilled water and an eyedropper handy.

fig.2 Typical spotting tools include a large magnifying glass, a set of high-quality brushes, some blotting paper, a porcelain palette to mix and dilute the spotting dye, a cup of distilled water and an eyedropper.

Spotting Brushes

Your set of fine-tip brushes needs to include only the smallest sizes. Start with a #000 (3/0) brush for larger spots, and attack smaller imperfections with a #00000 (5/0) brush. Be sure to buy only the best, evenly shaped, animal-hair brushes available, or your spotting efforts will be more tedious and frustrating than necessary. A high-quality brush features enough bristles to readily absorb the spotting fluid, while still forming a fine-point tip and allowing full control over the fluid amount released by varying the pressure applied to the tip of the brush.

Spotting Dyes

The best-suited materials for spotting monochrome prints are light-stable, black dyes and pigments, which are suspended in a quick-drying, water-soluble solution. This way, the spotting dye can be diluted with water to create any shade of gray from a barely visible light tone to a deep dark black. Once applied to the print, the dye is absorbed by the paper emulsion and penetrates into the fibers without appreciably changing the surface texture or its reflectance.

One prominent brand of spotting dye was Spotone, made by Retouch Methods, Inc., but unfortunately, the company no longer exists. They produced dyes of various colors, and by mixing them, one could match any print color, regardless of paper brand or toner used (see fig.3a). You may still be able to acquire a bottle of Spotone through a secondhand source, in which case, you will be glad to know that a single bottle will most likely last you a lifetime. The most useful color in the Spotone line of shades is #3 (neutral-black base), which has a colorless, black tone. By mixing #3 with small amounts of #2 (selenium brown), the tonality can be changed to closely match the tones of a typical sulfide or selenium-toned print. Further color matching is possible with #0 (olive black) and #1 (blue-black), but most spotting needs are adequately covered with Spotone #3 and #2. Marshall’s manufacture an alternative line of spotting dyes, called Spot-All (fig.3b). It is available in neutral-black, selenium-brown and blue-black. As of this writing, they are still available and just as easy to mix and apply as the Spotone products. I would not hesitate to work with either of these ink-based materials. Conversely, I had little success with products containing egg white, shellac or other glazing agents and lacquers. Their ingredients are not absorbed by the print, but build a hard, shiny layer on top of the emulsion, similar to a coat of paint. They alter the surface reflection and make tonal blending far more difficult than with penetrating inks.

fig.3a Spotone is, unfortunately, no longer available, but it is still possible to acquire this once-prominent brand of spotting dye through secondhand sources. By mixing various colors, any print tone, regardless of paper brand or toner used, can be matched.

fig.3b Marshall’s Spot-All dyes are still available, very similar to Spotone and work on the same principle. The dye is readily absorbed by the emulsion and paper fibers without appreciably changing the surface texture or its reflectance.

fig.3c Going back to the very roots of ink making, grind some solid India or China ink, mix it with an equal amount of gum arabic and dissolve together in distilled water. Gum arabic promotes print adhesion and controls the gloss level of the spotting dye.

fig.3d Special opaque liquids are used to cover up small holes in the negative emulsion. This way, they convert hard to remove, dark print spots into bright white spots, which are much easier to spot and blend into their surroundings.

If you are concerned about photographic product availability in general and monochrome, fine-print products in particular, spotting dyes should be the least of your worries. In the absence of specially made retouching products, one is well-served with archival inks as they are used in drafting and calligraphic applications. You might even go back to the very roots of ink making and produce your own spotting dyes from solid India or China Ink sticks (fig.3c). Grind some ink off the stick, mix it with an equal amount of gum arabic and dissolve together in distilled water. Alternatively, fill an ink rubbing stone with some water, rub the ink stick against the stone until the water turns deep dark and add some gum arabic to it.

Gum arabic promotes the adhesion between spotting dye and print emulsion while also controlling the gloss level of the dye. Therefore, use more gum arabic for spotting glossy prints than for spotting matt prints, and always try to match the surface reflection of the surrounding print area. Gum arabic can also be applied to professional spotting dyes in order to increase their inherent gloss levels.

fig.4a A light dye is mixed and applied numerous times to carefully build up the tonality required to fill the spot.

fig.4b Using a small brush to repeatedly apply a slightly darker dye to a series of lighter spots, a blemish is disguised and blends into the surrounding tones.

fig.5 An initial enlargement of the print revealed numerous imperfections of different origins. On the left, typical white spots and lines, caused by dust on the negative, are joined by a dark blemish (arrow), which was actually a tear in the paper of the studio background. On the right, there are more dust spots, together with a large dark spot, caused by a small emulsion defect in the negative.

fig.7 After retouching the negative and turning the dark spot into a white spot (right), a new enlargement was made. The dark blemish, caused by the tear in the paper, was bleached with Farmer’s Reducer during wet processing until it was lighter than its surroundings (left). These actions eliminated the need for etching, and the print is now ready for spotting.

fig.6 After making sure that all print imperfections are lighter than their surroundings, the print was carefully spotted. The goal is not to eliminate the imperfections altogether, but to move them from attention-grabbing boldness to inconspicuous obscurity. The telltale signs of spotting are only visible upon close inspection and by knowing where to look for them.

Dark spots on the print create a unique challenge to retouching efforts. They cannot be covered up with spotting dyes, because the dyes are made to build up tonality in the emulsion and not to paint over it. One way to remove dark spots is to bleach the print locally, while still wet, until the area is slightly lighter than its surroundings and spot it back in when dry. This is rather difficult with dark spots approaching maximum black, in which case, the blemish is best removed by turning a black spot into a white spot first. This is done by covering the corresponding negative area with an opaque liquid on the substrate-side of the film. This way, what printed as a black spot now prints as a white spot and can be easily disguised through print spotting. Any damage to the print emulsion, which is an unavoidable result of etching, is prevented by this method. Special opaque liquids are on the market (see fig.3d), but any near-opaque ink will work as well.

fig.8 Print spotting is not limited to removing dust and other print blemishes. As this example shows, it can also be used to retouch image-based imperfections. A few tiny holes in the stockings have been successfully repaired by simply correcting the damaged stitches with a small brush and some spotting dye.

Print Spotting Process

Professional print spotting takes a lot of practice and experience, but it does not take too long to learn the basic steps and improve the appearance of a print significantly. The main challenge is to understand the need to resist the initial impatience. Print spotting is not something that should be done in a rush, or the results will look rushed.

I do all my spotting after print mounting, because this has the benefit of being able to work with a perfectly flat print. However, it has the disadvantage of potentially wasting a mount-board if something goes terribly wrong during spotting, a risk that gradually diminishes with increasing spotting skills.

Clean up your work area, and make certain that it is dry, uncluttered and dust-free. Provide for bright and even lighting and get a comfortable chair. Get a large magnifying glass or use extra-strong reading glasses in addition to your corrective eyewear. Have all your spotting tools and materials ready, put on your gloves and continue with the following general steps:

1. Place a single drop of undiluted spotting dye into the saucer or porcelain palette (see fig.2). Using a mixing brush and distilled water, dilute the dye and create several drops of decreasing strength.

2. Place a spare piece of mount-board on top of the print, close to an area that needs spotting. Start with the lightest spots and the weakest dye.

3. Dip the tip of your brush into a dilution significantly weaker than the spot seems to require.

4. Blot the wet brush tip gently against some blotting paper. You have more control over spotting with a dry brush than with a wet brush.

5. Carefully touch the print with the tip of the brush. Aim for the center of the blemish. Do not stroke the brush; you are spotting, not brushing.

6. Compare the first spot you made to the tone of the surrounding area. If it is darker, quickly blot off what you can before it dries, apply a drop of distilled water to what is left and blot that off too. Repeating this a few times will not remove the stain at all, but it will make it less obvious.

7. The first spot application should look significantly lighter than the surrounding area. The goal is to start with a light dye and gradually build up density. Spots that are too light are easily darkened, but spots that are too dark are hard to remove and can ruin an otherwise perfect print.

8. Once you have the correct tone of dye, hold the brush straight up, and keep spotting the rest of the blemish by repeatedly applying tiny spots until it is filled in. Again, do not paint, spot. Be patient, and give the dye time to dry between applications.

9. After the first blemish is completely filled in, examine the print for blemishes of similar tone, and spot them next. While working on increasingly darker spots, slowly increase the strength of the dye. Repeat this procedure until all print imperfections are sufficiently disguised.

Final Hints

By far the most common spotting mistakes are to work with too wet of a brush and to use too dark of a dye. Until a certain spotting proficiency has been obtained, work with an additional copy of the print to practice and fine-tune the tonality of the dye, before spotting the actual print. When you feel more confident, simply use the trimmed white borders of the print itself to verify the tonality of the dye.

Correcting large blemishes takes a lot of tiny spots and effort. Resist the temptation to make larger spots. It quickly turns professional spotting into amateurish painting, and results will be perceived accordingly.

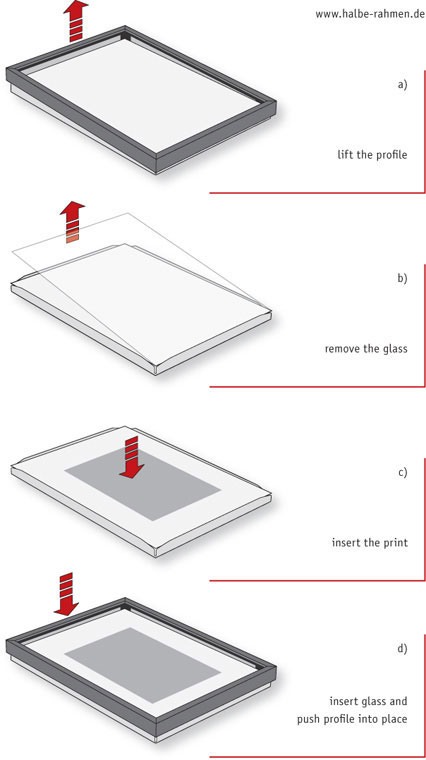

Framing and Displaying Prints

Fully protected and ready for the exhibition

A print’s appearance is improved significantly through mounting and matting, and subsequent spotting provides the cleanliness every good print deserves. However, framing a print behind glass is the ultimate aesthetic enhancement. No matter how much impact the print has on its own, if left unframed, it will always look inferior next to its framed counterpart. It takes a significant amount of time and money to frame a print professionally, but it is well worth the effort and expense for all prints going on display. Skillful framing gives our best prints the attention they deserve and us an opportunity to proudly exhibit our work.

The purpose of a frame is to isolate the print from its surroundings, enhance it aesthetically and protect it against dirt, dust and rough handling. Always select a frame design and color that complement the print without drawing any attention from it. A good frame supports the print without dominating it. Make sure to exhibit the print and not the frame.

The effort involved to turn a print into a framed print must not be underestimated. Mounting, matting and framing enough prints to fill a small exhibition can take a week or two of labor, and the materials alone might cost more than a camera. If you decide to frame your own prints, it certainly makes sense to be familiar with the materials and procedures available for framing and to find the best local sources for your supplies. But, even if you decide to take your prints to a professional framer, a little background on suitable framing materials and procedures helps to negotiate the best deal. A good frame will keep the print safe and representable for years to come.

fig.1 A frame isolates the print from the wall, enhances it aesthetically and protects it against dirt, dust and rough handling. Select a frame design and color that complement the print without competing with it.

Choosing a Frame

If we ignore all archival considerations, we are able to choose from an almost bewildering assortment of frame materials, including wood, metal and plastics. However, if we want to protect our photographs from harmful odors and fumes, the selection becomes much more limited. Wood contains aromatic oils, which vaporize over time and attack our photographs. Paints and varnishes emit harmful fumes, which do the same. The safest frame materials are chemically inert plastics and unpainted metals.

For aesthetic and chemical reasons, plastic frames are considered to be inferior and not suitable for high-quality framing. Mass-production plastic frames are often sold in combination with a cheap cardboard backing, which rules them out for archival reasons. This leaves us with unpainted metal frames.

Attention to weight, cost and corrosion issues make aluminum the professional frame material of choice. Extruded aluminum is light, relatively easy to cut and machine, and its smooth finish can be corrosion protected without paint. For all these reasons, I use anodized aluminum frames exclusively and committed to a personal standard of a matt black finish. The type of finish is a personal choice, but in my opinion, a thin black frame is the perfect companion for a white or light-gray overmat, creating enough contrast to clearly isolate it from the wall and quietly continue the style of the black and white photograph all the way to the edges of the frame. When a print is framed this way, and exhibited alongside others on a white wall, it always comes across as a well-coordinated, professional design concept that one can be proud of.

fig.2 Extruded aluminum profiles are the material of choice for professional framing. Here, the popular Nielsen & Bainbridge profile #15 offers enough room to comfortably fit one sheet of glass, two mat-boards and a backing board inside of it, while still leaving a gap to fit a number of springs, which later compress and securely hold the assembly in place.

A secondary consideration when choosing a frame is the selection of a suitable profile. Except for appearance of the exposed contour and a choice between smooth and sharp edges, this is mainly a matter of package requirements to fit the glass, mounted print and the backboard. Nielsen & Bainbridge, a well-known manufacturer of mounting and framing materials, offers a popular profile design called ‘#15’. It is about 1 inch tall and provides a 15mm pocket inside the profile to comfortably fit a 2mm sheet of glass, two 4-ply mat-boards and a 1/4 inch backboard, while still leaving a gap to fit a number of springs, which later compress and securely hold the assembly in place. Several framing material suppliers have copied this profile with only minor modifications.

fig.3 A print is put behind glass for protection, even though that degrades the print’s appearance, because it slightly changes the image color and reduces image contrast significantly.

Glazing Considerations