Chapter 2

State of the Market

TRENDS IN INTERNET USE

This chapter looks at the state of the market and current trends in Internet use. The discussion includes a description of the market, an overview of the state of e-commerce, and a look at specific trends in music sales online, including digital downloads.

Who’s Using the Internet?

According to the Pew Internet Project’s research in 2010, 79% of U.S. adults use the Internet, up slightly from 75% in 2007. Among the millennium generation, Internet use is at 95%, up from 93% in 2008 and from 92% in 2007. In 2011, Pew reported that two-thirds of U.S. adults had high-speed access at home, up from 47% in 2006. Point-topic.com puts U.S. broadband penetration at 77.5% of households in 2011.

Figure 2.1 Internet usage among age groups

(source: Pew Internet Project)

Figure 2.2 Percentage of Internet users engaged in online activities by age group

Ninety-three percent of teens use the Internet, yet it is the millinials who are more likely to use it for email, social interaction and to watch videos. Teens are the most predominant users for sending instant messages, playing online games and reading blogs. According to the PEW 2010 Generations and Technology study, “when teens do use email, they tend to use it more in formal situations or when communicating with adults [rather] than to communicate with friends” (Zickuhr, 2010). This is an important trend to remember when planning a marketing campaign aimed at teenagers.

Among adults, email and search engine use were the most popular of all online activities, with 92% of online users, according to a 2011 Pew research study (Purcell, 2011). Sixty-three percent of all adults have made an online purchase (not just online users). Fifty-one percent have listened to music online, up from 34% in 2006. And 27% have downloaded music files. An equal number (27%) state they have shared files from their computer with others.

Trends in e-Commerce

Many products are sold online as retailers shift some marketing efforts from retail stores or mail-order catalogs to online stores. Online commerce is just an extension of the mail-order business that has been around since the days of the first Sears-Roebuck catalog. In the 1960s and 1970s, credit cards and toll-free numbers helped to expand the mail-order industry. In the mid-1990s, as online became a household word and Internet use skyrocketed, consumers were still somewhat reluctant to purchase products online for a number of reasons: credit card security, lack of trust in the online retailers, inability to see the product before ordering, and clunky, complex storefronts and shopping carts.

Figure 2.3 Activities by age group 2010

In 1992, CompuServe offered its users the chance to buy products online. In 1994, Netscape introduced a browser capable of using encryption technology, called secure socket layers (commonly referred to as SSL), to transmit financial information for commercial transactions online. Then as shopping interfaces improved, more established stores began an online presence, alternative payment methods evolved, and consumers became more comfortable with making purchases online. In 1995, two online retail giants, Amazon and eBay, were introduced.

In January 2008, Nielsen Online reported that globally, 875 million consumers had shopped online, which is more than 85% of web users. This was up by 40% from 2006. South Korea had the highest percentage of online shoppers, with 99% of Internet users, followed by the United Kingdom, Germany, and Japan, all with 97%. In the United States, 94% of Internet users purchase products online according to the Nielsen report.

U.S. retail e-commerce sales reached $165.4 billion in 2010, up 14.8% from $144.1 billion in 2009 and $142 billion in 2008. This now makes up 4.3 percent of total 2010 retail sales according to the U.S. Census Bureau, (2011). Forrester measured it at $176 billion in 2010. E-commerce sales are expected to rise in the U.S. to $279 billion by 2015 (Forrester, 2011). The top-selling online retailers for 2010 were Amazon, Wal-Mart, eBay, Best Buy, JC Penney, Kohls, Target, Macys, and Sears.

Table 2.1 shows the most popular products to purchase online.

Figure 2.4 U.S. e-retail sales 2009–2015

Table 2.1 Most popular online purchases 2010

| Software, books, music, videos and flowers | 26% |

| Travel | 21% |

| Computer hardware, consumer electronics and office supplies | 16% |

| Apparel, footwear, jewelry and linens/home decorations | 13% |

| Health, beauty, and food and beverages | 8% |

| Toys, video games and sporting goods | 7% |

Source: EstoreFrontGuide

Online shoppers have become savvy. For the 2010 holiday shopping season, 58% of smartphone owners used the Internet and phone applications such as RedLaser to compare prices (CreditSense, 2011). Online consumers also rely on customer product reviews, with 57% stating in 2010 that they rely on customer reviews for their purchase decisions (Nielsen, 2010). According to Nielsen, shoppers tend to stick with shopping on sites they are familiar with, and 60% said they buy mostly from the same site. This information is important to consider for a small business as they decide how and where to sell their music online. Sixty percent of online shoppers used a credit card for purchases in 2007, whereas 25% had used PayPal. By 2011, PayPal’s market share was up to 18% of sales (Williams, 2011a).

Mobile ecommerce transactions are on the rise. Juniper Research stated in 2011 that over 100 million people globally were using mobile money services (transactions, balance check, transfer of funds, and so forth). This is expected to rise to 200 million by 2013, with much of the growth coming from Africa and the Middle East (Williams, 2011b). Mobile commerce will be addressed in Chapters 14 and 15.

Figure 2.5 Most popular gadgets

(source: Pew Center)

Music Sales Trends

Music is a dream product for e-commerce—it is one of only a handful of products that can be sold, distributed, and delivered all via the Internet. Of course, this is a double-edged sword. The ease with which music can be transferred over the Internet has also led to the continuing crisis of illegal file sharing. In an effort to monitor recorded music sales and determine trends and patterns, the industry in general and SoundScan in particular have come up with a way to measure digital album sales and compare them with music sales in previous years. When SoundScan first started tracking digital download sales, the unit of measurement for downloads was the single track, or in cases where the customer purchased the entire album, the unit of measurement was an album. But this did not give an accurate reflection of how music sales volume had changed, because most customers who download buy songs à la carte instead of in album form. In an attempt to more accurately compare previous years with the current sales trend, SoundScan came up with a unit of measurement called track equivalent albums (TEA), which means that 10 track downloads are counted as a single album. Thus, the total of all the downloaded singles is divided by ten and the resulting figure is added to album downloads and physical album units to give a total picture of “album” sales. Here is an example of how this works from Billboard. biz.

When albums are tallied using the formula of 10 digital track downloads equaling one album, the 582 million digital track downloads last year translates into 58.2 million albums, giving overall albums a total of 646.4 million units. The overall 2006 total of 646.4 million is a drop of 1.2% from 2005’s overall album sales of 654.1 million.

Ed Christman, Billboard, January 4, 2007

Figure 2.6 U.S. album sales in millions

(source: SoundScan)

Having established the TEA as a new unit of measurement, industry trends show the following: U.S. album sales have continued to slide every year from a high in 2000 of 785 million units to 443.4 million units in 2010 (including TEA). (Without the addition of the TEA, album units in 2010 were 326.2 million.) This represents a drop of 9.5% from the 2009 overall album sales of 489.8 million.

By the close of 2010, total album sales were down 12.7% from the previous year and down 10% for the holiday season. With track-equivalent albums factored in, the slide was 9.5% from 2009. The one bright spot has been digital album sales, which rose 13% in 2010. Meanwhile, retail stores continued to reduce the amount of shelf space they devoted to recorded music as online sales and digital downloads continued to erode at the physical unit market share. Sales of physical albums fell by nearly 19%, down to 240 million physical units. Digital album sales reached 86.3 million in 2010, a 13% increase over 2006. Digital album sales accounted for 26% of total album sales (without TEA included). Labels have been making an effort to convert singles buyers into digital album buyers, sometimes by not making à-la-carte tracks available and sometimes by deep discounting the album compared to the individual tracks. When pricing albums, the DIY musician should consider a similar pricing strategy.

In the United States, digital music accounted for 46% of all unit purchases in 2010, up from 40% in 2009 and 32% in 2008. More than 1.172 billion digital tracks were sold in 2010 (SoundScan) up from 1.16 billion in 2009 (a mere 1%). When all music formats are included (music videos, singles, albums, digital, etc.), the U.S. industry fell 2.4% in 2010. Year-to-date digital tracks for November 2011 were up 10% over the same time in the previous year as the industry overall showed a slight uptick for 2011.

U.S. Historical Trends

In 2004, catalog products accounted for 46% of all digital music sales compared with 35% for physical products. This was at a time when the replacement cycle for CDs was at an end. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, labels enjoyed record profits as consumers sought to replace their vinyl and cassette music collections with the improved digital CD format. As a result, catalog sales ran as high as 50% of units sold. Although the conversion from CD to MP3 or other portable format has generated some interest in catalog sales, consumers are not repurchasing music they already own on CD. Instead they are rounding out their catalog collection by cherry-picking songs they want in their library. The digital downloading format has, however, allowed major record labels to reissue recordings that previously had been deleted from the active catalog because, now, the cost of making them available is low.

Digital stores offer consumers a far greater virtual shelf space than the largest traditional brick and mortar stores. This means that a broader range of repertoire, including specialist, vintage or hard-to-find recordings is now available to fans.

IFPI Digital Music Report (2008)

The switch from CDs to digital downloading varies when separated out by genres. According to Nielsen SoundScan, digital album sales for 2010 were as follows: the genres of alternative, rock, soundtracks, and electronic showed an active downloading market, with fans of these genres more likely to select to download an album rather than buy the CD. Fans of country, R&B, Latin, and gospel are more likely to buy CDs than download albums. The DIY musician may want to take this under consideration when ordering the production of physical product, however sales at live shows continue to be dominated by physical product. This may change as mobile devices become more sophisticated and smartphones are more widespread.

GLOBAL DIGITAL MUSIC SALES

The International Federation of the Phonographic Industry’s (IFPI) Digital Music Reports for 2010 outlines some trends in global online music sales, including the following highlights:

• More than 400 licensed digital music services are available worldwide.

• Globally, digital music sales were up 9.2% in 2009 (IFPI). In 2010, digital sales continued to grow to account for about 29% of global sales, up from 15% in 2007.

• The increase in the value of the digital music market from 2004 to 2010 was 1000%.

• In 2010, the global digital music sector was worth an estimated US$ 4.6 billion, up six per cent on 2009.

• iTunes has sold more than 10 billion downloads since it was established in 2003.

• Digital album sales increased more sharply than singles in 2010, and accounted for 17.5 per cent of all album sales in the UK and 26.5 per cent in the U.S.

• A new business model for subscription-based services provides a two-tiered service for customers: a free, advertiser-supported version, and a paid, “ad free” subscription version and is now known as the “freemium” model.

Figure 2.7 U.S. album sales by format for CD and digital

(source: SoundScan)

Sales of music downloads have continued to grow, although that growth is slowing from the rapid pace of just a few years earlier. In 2007, digital sales in the United States accounted for 30% of all music sold according to the IFPI (2008), but only 23% according to SoundScan. In 2010, SoundScan reported digital album sales of over 26% of albums sold in the U.S. (NARM, 2012).

The number of licensed tracks available for sale online increased from 1 million in 2003 to more than 6 million in 2007. By 2010, that was up to 13 million licensed tracks according to the IFPI. Digital sales, especially album sales, have been stronger for catalog titles than their CD counterpart. In 2008, The Wall Street Journal commented:

[D]igital-album sales have consistently been more weighted to catalog and “deep catalog” items (generally speaking, releases more than 18 months old) than sales of physical CDs, and catalog and deep-catalog sales have shown stronger growth.

Fry (2008)

Figure 2.8 Mobile music revenue breakdown, global market worth US$14.4 billion in 2010

(source: Informa Telecoms and Media, 2011)

The South Korean market continues to lead the way in music shopping trends. In 2009, digital sales accounted for over 55.5% rising to 61.7% in 2010. According to Music and Copyright, the South Korean government has made a push for it to be the “most wired country in the world” (Music & Copyright, 2011).

Some countries are showing stronger sales of music via mobile devices than in the U.S. In Japan, digital music sales via mobile devices have topped 90% of all digital sales since 2007. Brazil reported 80% of digital sales via mobile devices in 2009; China reported that mobile sales comprised 90% of digital music sales in 2010 (Lai, 2011).

The sale of digital music via mobile devices was a growing field for several years but suffered a surprising slowdown in 2010, with a 28% drop in the U.S. due to the sharp decline in ringtone sales (Peoples, 2011). Declines for 2010 were also reported in France, Italy, Japan and Spain (Buskirk, 2011), now that the ringtone market has subsided.

Business Models

À-la-carte downloads have been the dominant business model for the first seven years of the digital music business, with iTunes leading the way. In the United States, iTunes surpassed Amazon and Target in 2007 to become the third largest music retailer, behind Wal-Mart and Best Buy. By early 2008, iTunes had moved to first place among music retailers. Lack of interoperability between services and devices hampered the development of the digital music market at first.1 Labels were resistant to license digital downloads for fear it would increase piracy. The industry overcame this concern by offering digital rights management (DRM) downloads. In 2007, iTunes and other digital retailers began to abandon DRM, first on a trial basis and then a larger rollout, to address consumer complaints of the lack of compatibility between hardware devices.

Table 2.2 Business models for monetizing recorded music

| Physical product | Sale of physical CDs in physical retail storesWalMart, Best Buy | Sale of physical CDs onlineCD Baby, Amazon |

| Digital sales | Sale of digital tracksiTunes, then Amazon | Sale of digital tracks stored on serverAmazon, then iTunes |

| Advertising-based | Advertiser-based userinfluenced radioPandora, Last FM | Advertiser-based on-demand listeningSpotify |

| Subscription-based | Subscription-based user-influenced radioPandora, Slacker | Subscription-based ondemand streamingRhapsody, Spotify |

The current business models for digital music income include: (1) the sales of digital tracks downloaded to consumer devices, (2) the sale of digital tracks stored on a central server (cloud computing) and available on demand, (3) advertising-based user-influenced radio streaming, (4) advertising-based on-demand listening, and (5) subscription-based on-demand streaming.

Labels, artists, and services have been experimenting with offering free, advertiser-supported music, either for streaming or downloading. Subscription-based services struggled early on in the digital realm, accounting for only 5% of global digital revenue (although these services grew 63% from mid-2005 to mid-2007). Now they are beginning to gain some ground with the rollout of mobile-device-based services and “freemium” tiered services. Freemium services offer a free, advertiser-supported limited functionality version of streaming “radio.” These services range from user-controlled on-demand playlists (such as Spotify) to user-influenced playlists (such as Pandora). The freemium business models appear to be more popular with consumers than either the free advertising-based model or the paid subscription-only model.

Unlike its predecessor SpiralFrog, which offered only the advertising-based on-demand model, Spotify, which made its debut in the U.S. in 2011, has based its business model on providing entry-level advertiser-supported on-demand music, with efforts to upsell to the subscription version.

Headway has been made in streaming radio, providing ad-supported free versions and subscription services through services such as Pandora and LastFM. In January 2008, CBS-owned LastFM announced it had licensing agreements with all major labels and 150,000 indies to provide full-track streaming music to fans. Pandora is a playlist-based streaming radio service with a tiered system, (much like Spotify), and playlists are determined by collaborative filtering, a process that uses statistical analyses to identify and categorize music.

TRENDS IN MUSIC DELIVERY AND MARKETING

The trends in the industry continue with music sales moving away from the CD and toward a variety of web-based music services. The attraction for digital downloads for consumers is in the à la carte or cherry picking that consumers prefer over purchasing an entire album. However, this is now changing: record labels are starting to bundle digital songs so they cannot be purchased separately for newly-released albums.

For 2010, paid song downloads in the U.S. jumped to 1.172 billion units, up from 1.159 billion in 2009 and from a mere 581.9 million in 2006. Nine individual songs exceeded 2 million in download sales for 2007 with that number jumping to 37 in 2010. Five songs broke 4 million in sales.

For 2010, downloads:

• The top-selling digital artist based on digital tracks from July 2004 to the end of 2010: Taylor Swift with 34.269 million tracks sold.

• The most downloaded track: “California Gurls” by Katy Perry, with 4.398 million tracks.

• The most downloaded album: Recovery by Eminem, with 852,000 units.

In the first edition of this book, a list of 14 trends in digital music for 2008, based upon the Stuart Dredge article in Tech Digest offered notable developments in the coming years. A glance back at those trends reveals that many of them have been adopted and/or deserve further discussion:

1. Advertiser-funded music. Spotify and Pandora, MOG, Rdio and We7 are gaining ground, although Dredge’s initial example SpiralFrog is no longer in business. Imeem has also vanished after being purchased by MySpace (Wray, 2010). The notion of giving away a track in exchange for exposure to an advertising message has been replaced with advertiser-supported streaming services—the same model commercial radio has used for decades. Spotify uses a unique method for delivering music to its subscribers; instead of relying on servers, Spotify uses a peer-to-peer network of subscribers that works like BitTorrent (Krietz & Niemelä, 2010). Less than 10% comes from their servers. MOG and Rdio both rely on integration with Facebook to drive revenue.

2. Music search engines (collaborative filtering). Collaborative filtering (CF) is the process of using large amounts of data to determine patterns of relevance. Wikipedia describes it as “a method of making automatic predictions (filtering) about the interests of a user by collecting preferences or taste information from many users (collaborating). The underlying assumption of the CF approach is that those who agreed in the past tend to agree again in the future.” Programs like Apple’s Genius use data from perhaps millions of users to determine and make recommendations of similarly liked songs. Programs like Pandora, with its music genome project, and LastFM depend on collaborative filtering to determine what songs to play next for each listener. Amazon makes extensive use of collaborative filtering to recommend specific products to each unique visitor.

3. Record labels taking on iTunes. Whether driven by labels or not, Amazon, and other retailers have made only slight inroads into the digital music market share. Despite the failed attempts of Doug Morris of Universal Music Group a few years ago to break Apple’s stronghold on retailing digital downloads, Apple still dominates the market with over 63% of the share. With the launch of their cloud player and by dropping prices, Amazon has moved up to 10–12% of the market (Wilson, 2011; Keizer, 2010), but at the expense of other retailers more so than Apple. In 2011, WalMart shuttered their MP3 store (Albanesius, 2011).

4. DRM-free music. Ubiquitous. All digital music providers have dropped much of their DRM music, so this is no longer an issue among consumers.

5. Music identification goes interactive. Shazam is a smart-phone-based music identification application that is available for most mobile phones. It uses an audio fingerprint to match a song it detects with its database. The user holds the microphone near the music source and the system will return the results in less than a minute. Shazam also connects users to online retailers to purchase songs identified by its users. Gracenote is a program originally designed to supply track information to users who ripped their personal copies of popular CDs. A connection to Gracenote through iTunes will download the track information to be included for song playlists. Gracenote has now extended their services to include music recognition and music recommendation (gracenote.com).

6. The rise of mobile music. Smartphones allow for music purchases to be downloaded directly to the device. Pandora, Spotify and others offer apps for consumers to listen to streaming audio, rather than download music (see item #5 under new trends). In April 2011, Sprint introduced Sprint Music Plus, a partnership with RealNetworks to offer mobile music downloads and streaming. Verizon teamed up with Rdio to offer a cloud-based music library of 8.5 million songs (Ankeny, 2011).

7. Bands giving away their music for free. Distribution via the Internet has allowed bands to share sample tracks with fans without incurring much expense. In 2008, Nine Inch Nails followed Radiohead’s lead to offer some tracks for free from its “Ghosts I-V” album. But both those bands already had a fan base in the millions (Netherby, 2008), a big factor in their success with music giveaways. In 2011, several bands experimented with giving away free song downloads to fans with smartphones at concerts via Bluetooth (Ehrlich, 2011). In 2011, the music blogs were alive with conversation debating the merits of giving away music with no agreement on the horizon.

8. The Net Neutrality policy is challenged. The FCC adopted rules in 2010 to protect net neutrality, but protects only lawful Internet traffic (Kang, 2010). The issue of neutrality is still to be addressed by legislators and the courts.

9. Music-based widgets. Widgets have made it easy for web users to transfer content from one web service to another in a simple, yet professional way. Instead of cutting and pasting, copying, or writing code, widgets provide the web user with a seamless, automated system for posting that interesting YouTube video on Facebook, dubbed “link and sell.” In his music blog, Chris Bracco states “the ‘web widget’ is an extremely effective application musicians use to make social networking easier” (Bracco, 2009). His article lists some uses of widgets, including: (1) uploading music for sale, (2) linking visitors to other social network sites featuring the artist, (3) syndication of information, and (4) collecting names for a mailing list.

10. Social networking goes musical. Social network sites have long realized the powerful role music plays in social interaction. Earlier entrants, such as imeem and iLike focused on music as the bond that brings users together. The next step has been how to monetize that opportunity. iTunes created Ping, allowing users to share their music tastes with friends. Others include iLike and BuzzNet. Facebook launched Facebook Music in fall 2011. Several streaming music providers (Spotify, Rdio, and MOG were ready with seamless integration. The goal for these services is to convert users to the subscription level.

11. Ticket sales go mobile. Mobile ticket sales are becoming popular for concerts, clubs, sporting events and other live entertainment events, accounting for 10% of ticket sales in 2011 (eTicketNews, 2011). (More on this in Chapter 15.)

To the trends discussed above, the following new trends are added from various sources and observation:

1. Cloud computing. Cloud computing is defined as hosted services for storing and delivering personal content over the Internet. In other words, software or your content that would normally be posted on your computer is, instead, hosted on a server and accessed by your computer via the Internet. What makes this a new trend is the fact that Amazon, iTunes and others are now offering consumers the option to store their music collections in the cloud so they can be accessed from remote locations. Ironically enough, back in 1999, My.MP3.com was an earlier player in the cloud game, offering consumers the option to store their music “in the cloud.” They were sued by the record labels and dropped the idea.

2. Digital mobility at home and on the go. The combination of systems such as Apple’s AirPlay, Airfoil and others has made it possible for various computer units in the home to communicate with one another, sending content back and forth. The introduction of the tablet format for computers had further hastened the way some consumers use computer-based services, especially media consumption. Movies and music can now be streamed from one device to another in the home and via Wi-Fi connections outside the home.

3. Marketing with QR codes and Microsoft tags. Quick response codes and Microsoft tags use an advanced version of barcode technology to implant the codes into print media. Smartphone applications allow the phone to “read” the barcode and respond as if it was a hot link to the web page. Smartphone users are instantly directed to the web page address encoded in the tag. (See Chapter 14.) The tags are available at no cost to anyone with a web site to promote. Search under “QR tag generators” or visit “Microsoft Tag” online. Tag providers also offer analytics of tag usage by consumers.

4. Nearfield communications (NFC). NFC allows for simplified transactions, data exchange, and wireless connections between two devices in close proximity to each other, usually by no more than a few centimeters (NFC, 2011). It is anticipated that the technology will be used for mobile transactions, in addition to “sharing and pairing.” It has been compared with the EZ Pass devices used at highway toll booths, except that it is two-way (Nosowitz, 2011).

5. Internet Service Providers (ISP) and mobile service providers teaming up with on-demand or downloadable music services. In 2010, several partnerships were formed between ISP providers and branded music services such as Spotify. In other instances, ISPs created their own branded music services offering a combination of streaming on demand and downloads. Mobile service providers such as Melon in South Korea, Vodaphone in Europe and Slacker in the U.S. began offering subscription-based music streaming services.

CURRENT ONLINE ENVIRONMENT FOR ENTREPRENEURS

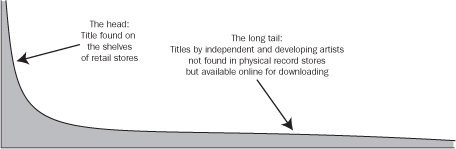

Chris Anderson, in his book The Long Tail, describes how new Internet applications, including collaborative filtering, are moving the market away from the “head” consisting of the top-selling artists, writers, movies, and so forth and moving members of the market “down the tail” by allowing them to discover new, less popular products easily that would have, under previous circumstances, gone unnoticed in the marketplace.

The “leveling” effect that technology has created is resulting in lowering the barriers of entry for many small businesses in many areas. Costs associated with advertising, distribution and retailing have been reduced. Geographic barriers are melting. Access to business knowledge and contacts is more readily available. David Ingram from Demand Media states:

The Internet has all but leveled the playing field for small-business marketers competing against established businesses. With advanced video and graphics editing software, small-business owners can create professional marketing materials that reach thousands or millions of viewers online. Entrepreneurs can take advantage of cost-efficient web marketing tools such as Google AdWords to spread targeted marketing messages to a broad audience or a select niche. Several small businesses can share expensive advertising space online through banner- and traffic-swaps.

David Ingram, The Impact of Information Technology on Small Business

Figure 2.9 The head and the long tail

The development of social networking sites dedicated to discovering and sharing new music brings hope that the millions of unsigned musicians who have recently acquired the technology to create high-quality recordings will now be able to achieve a moderate level of success, creating a middle class of professional entertainers that has been missing in the previous decades. A “record deal” with a major record label may no longer be necessary to enjoy the success of having a large fan base to purchase recorded music, concert tickets, and artist memorabilia. Several chapters in this book are dedicated to outlining how to make this happen.

In other words, the self-promoted artist and those on small independent labels now have several outlets through which they can promote and sell music to a wider market than in the past, basically lowering the barrier of entry into the music business. Not only are these small enterprises able to promote and distribute music at a fraction of the previous cost, but the newer, sophisticated techniques for music discovery via search engines, collaborative-filtering software, and music networking sites make it easier for music fans to discover and find some of these lesser-known artists that appeal to them. The merits of the long tail theory have been challenged but the concept remains: the barriers to entry have been leveled. Small businesses now have access to many of the same tools used by large media corporations and can make inroads into their market share. Technology has impacted the music business in three ways:

1. The production of music. Desktop recording has enabled musicians to create a commercially viable recording.

2. Promotion and distribution. The Web and social networking have provided a means for the DIY musician to promote their recordings without the large expenses associated with major labels.

3. Consumers can find new music. Many new features, such as iTunes’ Genius, have enabled consumers to seek and discover music they otherwise would have no knowledge about.

CONCLUSION

The Internet continues to siphon off recorded music sales and is accounting for a larger percentage of total retail sales in many sectors. Record labels are finding new, creative ways to sell music as the role of the CD as the primary source of revenue for recorded music diminishes. New business models are being developed that generate revenue from advertising on music-related sites, advertiser-sponsored music downloads and streaming, and using music as a promotional tool to sell other products such as concert tickets or portable music devices. Record labels have instituted something called a “360-degree model,” where they are responsible for and share in all revenue streams in an artist’s career. Then the music can be used as a tool to generate revenue elsewhere that is shared between the artist and the label. The DIY artists and small indie labels have always operated under the “360” model. As these models develop and as record labels scramble to remain relevant, recorded music is beginning to generate profits in new and unusual ways.

Glossary

Collaborative filteringSoftware applications that offer recommendations to consumers based on that consumer’s pattern of behavior and consumption and drawn from analyses of the consumption behavior of a large aggregate of consumers.

Digital rights management (DRM)Copyright protection software incorporated into music files so that they cannot be shared freely with peers or copied to more than the maximum number of specific portable devices.

ExclusivesCDs or special versions of albums available only in that chain’s stores.

Internet service providers (ISP)An ISP (Internet service provider) is a company that provides individuals and other companies access to the Internet and other related services.

Loss leaderProducts are sold at below wholesale cost as an incentive to bring customers into the store so that they may purchase additional products with adequate markup to cover the losses of the sale product.

Music-based widgetsA portable chunk of code that an end user can install and execute within any separate HTML-based web page without requiring additional configuration. End users use them to install add-ons such as iLike and Snocap to social networking pages.

SideloadingThe act of loading content on to a mobile communication device through a port in the device rather than downloading through the wireless system.

Track equivalent albums (TEA)Ten track downloads are counted as a single album. All the downloaded singles are divided by ten and the resulting figure is added to album downloads and physical album units to give a total picture of “album” sales.

Notes

1 Initially, labels sought to protect their music by including copy protection on music provided to legal downloading services so that the files could not be copied and shared with other consumers. As a result, different standards and platforms were developed that prevented the seamless transfer from one type of platform (such as ipod) to another (Zune). This process is referred to as digital rights management.

Bibliography

Albanesius, Chloe (2011). Walmart shutting down MP3 store. PCMag.com. http://www.pcmag.com/article2/0,2817,2390854,00.asp

Ankeny, Jason (2011). Mobile music remixed: Operators tune in new features and services. FierceMobileContent. http://www.fiercemobilecontent.com/special-reports/mobile-musicremixed-operators-tune-new-features-and-services

Bracco, C. (2009). A widgets primer and useful ones for musicians. http://tightmix.wordpress.com/2009/03/02/a-widgets-primer-useful-ones-for-musicians/

Buskirk, Eliot Van (2011). Mobile carriers are doing it wrong, music-wise. evolver.FM. http://evolver.fm/2011/06/13/mobile-carriers-are-doing-it-wrong-music-wise/

Christman, Ed (2007, January 4). Nielsen SoundScan releases year-end sales data. Billboard. http://www.billboard.biz/bbbiz/content_display/industry/e3iXZLO0IdrWuAOeIRwz3vtYA%3D%3D

CreditSense (2011). 2010 Online e-commerce sales skyrocket during holiday season. CreditSense. http://www.creditnet.com/blog/credit-news/2010-online-e-commerce-sales-skyrocket-duringholiday-season.

Dredge, Stuart (2008, January 4). 30 trends in digital music: the full list. Tech Digest, http://techdigest.tv/2008/01/30_trends_in_di_6.html.

DMW Daily (2008, January 3). U.S. album sales down 9.5%, digital sales up 45% in 2007, www.dmwmedia.com/news/2008/01/03/u.s.-album-sales-down-9.5%25,-digital-sales-45%25-2007.

E-Commerce as a revenue stream. http://newmedia.medill.northwestern.edu/courses/nmpspring01/brown/Revstream/history.htm.

Ehrlich, Brenna (2011). Band plans to give fans free music via bluetooth during concert. Mashable.com. http://mashable.com/2011/08/08/data-romance-bluetooth/

ETicketNews (2011). Report: mobile ticketing accounts for 10 percent of total ticket sales,mobile commerce in 2011—will see a boom in the near future. http://www.euticketnews.com/201103231155/report-mobile-ticketing-accounts-for-10-percent-of-total-ticket-salesmobile-commerce-in-2011-will-see-a-boom-in-the-near-future.html

Forrester (2011). U.S. online retail forecast, 2010 to 2015. http://www.forrester.com/rb/Research/us_online_retail_forecast,_2010_to_2015/q/id/58596/t/2

Fry, Jason (2008, January 27). Beyond the album: 2007 brings new signs that the era of a beloved musical form is ending. Wall Street Journal.

IFPI Digital Music Report (2008). www.ifpi.org.

Ingram, David (n.d.). The impact of information technology on small business. Demand media. http://smallbusiness.chron.com/impact-information-technology-small-business-5255.html

Kang, Cecilia (2010). FCC passes first net neutrality rules. The Washington Post. http://voices.washingtonpost.com/posttech/2010/12/fcc.html?wpisrc=nl_polalert

Keizer, Gregg (2010). Apple controls 70% of U.S. music download biz. ComputerWorld. http://www.computerworld.com/s/article/9177395/Apple_controls_70_of_U.S._music_download_biz

Kreitz, Gunnar and Fredrik Niemela, (2010) Spotify – large scale, low latency, P2P music-on-demand streaming, Proceedings of IEEE P2P. Royal Institute of Technology, and Spotify, Stockholm, Sweden. http://www.csc.kth.se/~gkreitz/spotify-p2p10/

Lai, Herman (2011). China’s online music sales up by 14 percent. MicGadget. http://micgadget.com/11733/chinas-online-music-sales-up-by-14-percent/

Los Angeles Times (2011). Pandora posts loss as revenue increases 117%. August 25, 2011. http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/entertainmentnewsbuzz/2011/08/pandoras-earnings-beatexpectations-drives-shares-up.html

Music-on-Demand Streaming. White Paper. http://www.csc.kth.se/~gkreitz/spotify-p2p10/spotifyp2p10.pdf

Music & Copyright (2011). South Korea continues to develop as a model for future recorded-music markets. Music & Copyright. http://musicandcopyright.wordpress.com/2011/03/10/south-koreacontinues-to-develop-as-a-model-for-future-recorded-music-markets/

National Association of Recording Merchandisers (NARM) (2012). The Nielsen Company & Billboard’s 2011 Music Industry Report. News release January 5, 2012. http://narm.com/PDF/NielsenMusic2011YEUpdate.pdf

NFC Forum (2011). What is NFC? http://www.nfc-forum.org/aboutnfc/.

Netherby, Jennifer (2008). More bands embrace the option of giving away music. Reuters News Service. http://www.reuters.com/article/2008/03/15/us-free-idUSN1543936020080315

Nielsen (2010). Global trends in online shopping: A Nielsen global consumer report, June 2010. http://hk.nielsen.com/documents/Q12010OnlineShoppingTrendsReport.pdf

Nosowitz, Dan (2011, March 1). Everything you need to know about near field communication. Popular Science Magazine.

Peoples, Glenn (2011). Mobile sales plummet, subscription revenues slip in RIAA 2010 year-end stats. Billboard. http://www.printthis.clickability.com/pt/cpt?expire=&title=Mobile+Sales+Plummet%2C+Subscription+Revenues+Slip+in+RIAA+2010+Year-End+Stats&urlID=451884727&action=cpt&partnerID=81056&fb=Y&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.billboard.biz%2Fbbbiz%2Findustry%2Fdigital-and-mobile%2Fmobile-sales-plummet-subscriptionrevenues-1005160832.story

Pew Internet and American Life Project. www.pewinternet.org.

Point-Topic.com. World broadband penetration rankings by household. http://www.websiteoptimization.com/bw/1107/

Purcell, Kristin (2011). Search and email still top the list of most popular online activities. Pew Internet and American Life Project.

Williams, P. (2011a). PayPal’s market share increases to 18% as more people use ecommerce,HostWay Global Web Solutions. http://www.hostway.co.uk/news/ecommerce/paypals-marketshare-increases-to-18-as-more-people-use-ecommerce-800400807.html

Williams, P. (2011b). Ecommerce could rise after report says mobile money users set to double by 2013. HostWay Global Web Solutions. http://www.hostway.co.uk/news/ecommerce/ecommercecould-rise-after-report-says-mobile-money-users-set-to-double-by-2013-800394957.html

Wilson, Renee (2011). Amazon drops song prices to take market share from iTunes. Digital Journal. http://digitaljournal.com/article/306183

Wray, S. (2010). We7 shows ad-funded model can work for online music. The Guardian. April 28, 2010. http://www.guardian.co.uk/media/2010/apr/28/we7-online-music-service/print

U.S. Census Data (2011). Estats.

Zickuhr, Kathryn (2010). Generations 2010. Pew Internet and American Life Project.