CHAPTER THREE

Changing the Organization

IN THIS CHAPTER, THE ORGANIZATION learns how to take the fundamental Workforce Asset Management (WAM) vision and principles, and build its own individual, scaled model. Beginning with the preliminary step of creating a business case for WAM, this chapter covers other essential stages of preparation such as planning for and assessing return on investment (ROI), discussing different financing methods for workforce management (WFM) technology and equipment, and leading negotiation efforts. After the initial transformation of the workforce, direction on how the workforce management office (WMO) takes on the responsibility of maintenance and upkeep of WAM infrastructure and practice is given. The leadership role of the workface asset management professional (WAM-Pro) is described as the organization encounters new requirements and evaluates new investments in WFM solutions.

- Recognize the basic components of the WAM business case and how to position it to top management.

- Define and track budget requirements, goals, and objectives needed to make investment decisions, calculate expenditures, and identify ROI.

- Evaluate the common sources and potential alternatives for workforce management (WFM) equipment financing, as well as the criteria, benefits, and risks associated with the different financing options.

- Identify the positive practices and strategic roles of negotiation from buyer and vendor perspectives.

3.1 DEVELOPING THE BUSINESS CASE

When considering a new or enhanced WFM solution, it is critical to develop a business case. The process will help assess whether a new system—the processes and technology—makes sense for your organization and the threshold at which new technology will both meet your business needs and deliver an acceptable ROI. The final business case document should enable you to articulate your plan to senior management, supporting not only the funding decision but also helping to secure buy-in for the changes at all levels of the organization as you implement.

A business case is not simply an argument to proceed. A well-executed assessment takes an honest look at the needs and opportunities in the context of what is happening within the organization, and it determines whether the organization is ready or has the necessary infrastructure to make things workable. It should involve specific research that identifies the need, the investment, the potential obstacles, and the potential gains, both financial and functional. It should involve a careful assessment and mapping of the as is process so that gaps and inefficiencies can be identified. This may mean going to the shop floor level to understand where and how employees do their jobs as well as conversations with executives around what is needed to move the organization forward.

Proceeding to assess or implement a system without benefit of a clearly developed business case can create problems; not only in obtaining buy-in and needed support throughout, but also in putting the organization at risk of developing or purchasing a solution that may not meet the present needs fully, or that may not be sufficient as the company evolves.

When properly constructed, a business case should accomplish these five core goals:

(a) Selecting a Team to Develop the Business Case

The business case will be strongest if input can be incorporated from key stakeholders and prospective team members. This might include IT, payroll, accounting, and operations. Ascertain what each stakeholder hopes to achieve and seek to establish early agreement on overriding goals for the solution. The goals should be a focused few and at a high level—sufficiently succinct for the team to be able to remember easily as their guiding principle(s).

At a minimum, assign the following roles. Note that one person may fill multiple roles particularly in smaller organizations:

- Project sponsor. A high-level, primary stakeholder in the business area who will benefit most from a successful outcome. The sponsor should be someone in a position to provide direction and set priorities throughout development and implementation, allocate needed resources, and monitor that the project receives proper organizational support. The sponsor will likely be less involved on a day-to-day basis.

- Business owner. The leader of the area that will eventually take ownership and maintenance responsibility for the new system. This would likely be the WMO director or officer, a payroll, human resources, or a shared services director. In organizations not yet forming around a WMO, the traditional owners are finance, payroll manager, and human resource information systems (HRIS) and IT at times.

- Project manager. An employee responsible for leading the project from inception to completion, including concept development, design, testing, training, and delivery. The project manager (PM) will also develop and manage the charter, scope, budget, and schedule for the project.

- Product manager. The employee who will take the lead on selection of a vendor and system to be purchased.

- Business analyst. The person who will facilitate bringing multiple groups together to define the scope of the system, gather requirements from the subject matter experts (SMEs) and other stakeholders, use analysis skills to document as is and to be processes, and communicate methods for closing the gaps and achieving ROI.

- (Optional): External subject matter specialists. It may be advisable to engage an outside consultant with the experience and technical skills to assist the internal team in assessing needs and solutions. Although internal staff can recognize business and operational requirements, a good external consultant will understand which technologies and strategies can best support the project objectives, and will also help the team anticipate gaps or glitches that might undermine achievement. External specialists also evaluate conditions without being influenced by politics or organizational history giving the process objective input. Specialists with a considerable background in WAM can also provide a measure of reasonableness and viability to the business case based on past experience.

(b) Preliminary and Final Business Cases

Development of the business case will typically occur in two stages: a preliminary brief and a second, detailed summary of the proposed solution. These stages are described in the following sections. Note that in some organizations development and documentation of the business case will be incorporated into the overall systems development life-cycle process (SDLC).

i. Phase 1: The Preliminary Executive Brief

The first step is a preliminary, informal executive brief that introduces the problem and helps to garner corporate buy-in for further action. This document begins the process of socializing the concept internally. Although the preliminary brief will be broad, it should, at a minimum, identify the business or operational problem, explore the possibilities for improvement, and outline the general range of appropriate technology options. The successful preliminary brief will generate decision-maker approval to proceed with additional research, planning, and vendor/system selection.

Senior management may not be thinking about WFM as a problem let alone as a solution. Be prepared to educate management by articulating the challenges, explaining the options, demonstrating unfamiliar interdependencies between WFM, and outlining potential benefits (using examples, as may be necessary). A detailed and organized business case can improve the likelihood of rallying support for a WFM initiative. Therefore, the initial briefing may include a vision statement and efforts to socialize new concepts in management and organization as well as new technologies. This brief should also address the age-old question of What's in it for me?—in other words, why management should take this initiative.

ii. Phase 2: The Formal, Published Business Case

The formal business case is a structured document that presents the problems in deeper detail and documents the proposed solution in concrete, specific terms. The formal business case articulates the recommended course of action, actual costs, and preferred vendor and system. It should also detail expected results and quantify benefits (who will benefit and how).

More important, the formal business case document is developed only after the solutions are known. It is not suggesting but presenting conclusions about a course of action.

A business case should serve as the road map to guide the scope and maintain focus on objectives for implementation. It should also serve as a reference point to guide implementers should there be confusion or disagreement on direction as the project gets under way. The business case may go through a final acceptance stage with senior leadership where prioritization and financial disbursements are decided.

(c) Techniques to Define the Problem

The business case should elevate the need for a WFM system beyond a single department or group and link it directly to the strategic, operational, and financial goals of the organization. It helps to begin by identifying the problems causing the most pain in the organization as well as the company's larger business objectives, whether these seem to be directly related to time and labor management.

Explore how the proposed solution might address these needs, recognizing that labor management technology will have an impact on issues from costs, staffing, and productivity to risk and revenue. During research, get buy-in from all levels. Do not limit conversations to upper management. Seek ground-up input and honest buy-in from colleagues from every level of corporate infrastructure. This will be especially important in helping to refine initial assumptions.

The research tools discussed in the following sections help to conduct an analysis in logical and time-efficient stages. These tools are helpful when defining the overall business case.

i. Feasibility Study

Typically used when formulating the executive brief, this is a high-level review of problems, opportunities, constraints, and directives related to the current system. The study helps to determine whether there is, indeed, a business need for the system. It considers not only performance but also information management, economics, efficiencies, and control—keeping in mind all stakeholders.

ii. System Study/Summary Analysis

If the feasibility study results require continuation, the next step is a system study. This will typically occur once the executive brief has been vetted and the project has been given the go-ahead. Findings from this deeper dive study will be used to inform the selection of a system and vendor.

The system study establishes a baseline understanding of current approaches and infrastructure, examining technologies and processes, both. The goal is to ascertain what is rather than focusing on solutions. The system study will review and measure the materials, systems (manual and automated), and processes in the current time management infrastructure. Include deeper assessments of problems and strengths (what is working/what is not) and consider these in the context of where the company or organization is headed in the coming few years. It helps to utilize root cause analyses (see “Are You Solving the Right Problem?”) to uncover trouble spots that may not be readily apparent.

System study summary: Include a summary analysis of the current systems and a recommendation for next steps, including an explanation of how the organization should plan to acquire a solution.

iii. Requirements Analysis

Once a system study is evaluated and the approach is confirmed, then the requirements analysis will document the features and functions required in the new solution, including:

- Existing functionality to maintain.

- Features necessary to address the problems identified in the system study.

- New capabilities to help the organization meet its strategic goals.

- Wish list add-ons that may not require additional expenditure but that might be available as part of a package arrangement (but be careful not to let the business case lose credibility by overfocusing on unneeded bells and whistles). Focus on meeting the summary statement goals.

(d) Create the Business Case

With the feasibility study, the system study, and the requirements analysis you should be able to begin the process of establishing the rationale for an upgrade, a new solution, or a full organizational transformation around a technology. This is a formal business case. It should also include an assessment of benefits, efficiencies to be gained, and return on investment.

Include the following information categories:

- Executive summary

- Purpose

- Background

- Project officers

- Business requirements:

- Strategic

- Operational

- Justifications

- Project goals and objectives

- Scope of project

- Manpower needs

- Costs and time frame

- Business risks and mitigation of those risks

- Project risks and mitigation of those risks

- Alternatives

- Economic assessment

- Costs and cash flows

- ROI (NPV/MIRR)

- Funding source

- Recommendation

- Clearly communicates the goals, mission, or vision of this project and how it aligns with the organization's objectives.

- Provides clear directives and defined roles and responsibilities for team members.

- Offers a reference point for team members to keep track of efforts and an opportunity to check and realign when necessary.

- Demonstrates reasoning behind giving this project priority.

- Displays the potential gains and measures the gap between the current and desired state.

- Establishes a reliable and measureable target for project team members.

- Sets the expectation for what the project will secure or achieve; outlines the impacts—cost, timing, resources, and so on—of the project.2

- During disagreement over the direction of the project, pace of the work or priorities.

- For project status check-ins or updates, use as a guide or measuring tool.

- When new information prompts consideration of the scope of the project. Should new activities, budget, or resources be added?

- To prioritize remaining resources when there are cost overruns before project completion.

- To direct/redirect resources or assign/reassign responsibilities at the beginning or midway through the project.

- When communicating with leadership and end users to maintain focus on the vision for the new systems and practices.

- If a product upgrade is suggested, review the charter for the defined reasons the system is in place and whether new functionality aligns with the charter sufficiently to justify additional investments.

3.2 FINANCIAL PLANNING AND RETURN ON INVESTMENT6

When organizations have a WFM project that may require substantial funding, management is interested in what the return on investment (ROI) will be for that project. Or in plain words, the amount of financial compensation the organization will receive from investing in the project. Whereas operational and strategic benefits may also be derived from the investment, ultimately these impact the organization's bottom line and must be a worthy diversion of available funds and assets. The financial benefit or return that a project provides will likely be the deciding factor whether the project is approved or denied. This is especially true with workforce management systems where there are usually many upfront costs and business process changes that may occur related to that implementation.

However, many organizations either have difficulty determining the ROI or develop an ROI that is inaccurate or misleading. The lack of accuracy can be viewed as incompetence or malfeasance with the intent of getting the project approved regardless of benefit for the organization. No matter the reason, an inaccurate ROI can be detrimental to the organization and the careers of those who developed and presented the ROI to receive approval for the project. Lack of a clearly defined ROI can also allow the implementation to become sidetracked by objectives that may impede the system's ability to drive the expected benefits.

This section provides a background on developing an ROI when implementing WFM systems. There are also guidelines to prevent bogus, contrived, or faulty approaches that may mislead the organization or cause an embarrassing situation that could inappropriately impact the organization and investors negatively. However, this section is not a course in finance or accounting. The intent is not to teach finance, but rather, to enable the WAM-Pro to manage and support the process that leads to calculating an ROI and considerations on how to develop a more complete ROI.

(a) Developing a Return on Investment for Small versus Large Companies

When addressing ROI concerns, the real question is: Will the organization achieve a financial payback that equals more money than what was paid? The only way to get an accurate answer for this is to do an ROI analysis to help make the decision about purchasing or modifications.

With large companies spending substantial amounts of money on a new WFM system, there should be significant efforts to determine the ROI and selecting which system will produce the best ROI. Larger companies will have more complex issues to address and usually many policies and processes that impact the organization and how it does business. However, what about the small business that does not need a large or complex WFM solution? What is the best approach for them to determine an ROI for WFM system implementations?

A question asked by small business and many of their vendors is, What type of ROI calculation is really needed? The answer may be fuzzy with a lot of “it all depends.” There is no specific answer to this question. However, there are some general guidelines presented here to help with that decision. They are not all inclusive, but do assist with determining an approach for calculating ROI.

The ROI approach outlined in the main part of the section is scalable and can be used for large and small businesses. Larger organizations will need more information for the calculations than small organizations will need. Nevertheless, the approach is the same. The primary recommendation for organizations, regardless of size, is that a detailed ROI be completed. It protects the organization from investing in products or functionality they may not need, and coordinates how expenditures are managed and reported financially. So, the real question is not about doing an ROI for a WFM system, but it is more about how big an effort should be undertaken.

(b) Considerations for a Smaller Business WFM System ROI

The following are some considerations for the small business when calculating a WFM ROI:

- What is the size and scope of your organization? If your business is small and operations are limited (for example, if there are less than 25 people in the entire business and the company produces a narrow set of products or services), the amount of effort should be less than with a larger, more complex organization. It will be easier to calculate time savings and there will be less hardware, software, communications devices, training, and other support items to purchase. The overall expense and savings are easier to calculate and the amount of funds to purchase the needed items will be less.

- Have you defined your WFM system-related problem? As a business, the problems related to WFM or other processes need to be identified. Is it a system, compliance, competitive advantage, or a manpower issue? The reasons for purchasing a new WFM system should be specific and be addressed by the WFM solution.

- Are your WFM needs straightforward and limited to time collection and reporting? If the reason a new WFM system is needed is due to having limited time to complete the WFM processes, then the justification is easy but still needs to have some metrics associated with the problem. The WAM-Pro can provide metrics about how much time it is currently taking timekeepers, employees, and managers as well as payroll and reporting personnel to complete routine activities and troubleshoot and correct problems. These metrics are compared to time saved when the system relieves personnel from these tasks. Having that information gives the organization measures of how this manual work is diverting precious resources and how much that costs. It may help avoid having to hire additional personnel to complete the work.

- Have you talked with vendors who have WFM products or services that could address your problems? If you have defined your problem, then vendors with solutions to the business problem can be approached to determine how they will solve the problem and how much it would cost. Care is needed to prevent purchasing WFM systems and features that are not needed. However, most systems come with bundled features, so some functions that are not needed will still be included with the solution to the business problem. In general, the smaller and less complex the system, the fewer the bundled functions. The calculations should be based only on the features that are needed to solve the problem today, unless significant growth in size and complexity are anticipated. Those bundled but unused features could be important not too far into the future, and buying early could avoid having to repeat the purchasing process down the road. The WAM-Pro can help determine if the system needs to be something the organization can grow into.

- Do you have staff that can perform the ROI calculations? Quite often a business is not interested in doing a detailed ROI because they do not have the time, manpower, or knowledge on how to do the calculations. In this situation, the WAM-Pro should have an accounting firm assist with the calculations or temporarily hire someone to help with the calculations. Not having the time, the manpower, or the knowledge to do a proper ROI analysis is a poor justification for putting a business at risk from a faulty purchase.

- Do you have an accounting firm that can perform the calculation? If a business cannot do an ROI calculation, then there are many accounting firms, business schools, and WAM-Pros that can assist with the effort without much cost.

- Do you really care or does it matter to your organization what the ROI is? In some cases small businesses do not really care about what the ROI is, and only need the help of a new WFM system to complete their work and meet compliance requirements. Although not recommended, if organizations do not care about a calculated ROI, then they do not necessarily need to do one beyond documenting the cost estimates and why they feel they need the WFM system.

- Are you just completing a ballpark ROI? In some cases only a nondetailed ballpark ROI is needed by a small business. This means that only the tangible cost of the WFM system or service is used in the calculation against a rough estimate cost savings. This approach may not be accurate and does not portray the actual ROI or show the real costs or savings. It does provide a rough idea as to whether the purchase is worth it to the organization. If the WFM system cost and implementation is considered as inexpensive to the organization, it may not matter that ROI details are not developed. However, if a business is struggling to survive, it may be necessary to develop the ROI information in detail to reduce financial risks and the possible selection of a system or service that is not needed.

- How should you use vendor calculators and cost-saving estimates? A word of caution about calculators provided by vendors to determine the ROI and savings from a WFM system purchase: Many of the calculators use limited information and do not consider intangible items and impacts on the organization. Generally, they are based on what the system will cost, and an estimated number of hours that will be saved. In effect, this is the ballpark ROI calculation and should be used with the understanding that the calculation is limited and does not have many of the other items that may incur a present or future cost or savings. Examples of this include training and training materials; support; telecommunications; maintenance and repair; upgrades; interface development; impact on, and rework of, related systems and other hardware; networking; and supplemental software. Savings examples beyond efficiencies include reducing the amount of premium pays or absences, for example.

(c) Estimating Cost Savings

A simple approach for determining cost savings is to use a spreadsheet to do the calculations for a rough ROI. The calculations are comprised of categories and factors. The list is not all inclusive and there may be additional direct labor efforts that also experience time saved by using the WFM system. Some of the categories include the following efforts in time saved:

- Data entry

- Manual calculations of hours and payments

- Reduced human error

- Budget forecasting (e.g., overtime, premium pays)

- Sharing information between business functions

- Auditing and correcting time records

- Creating time reports

- Creating and managing leave reports

- Lost or inflated time

- Filing of paperwork

- Scheduling workers and assigning shift work

The factors that may be used for the calculation may include:

- Number of employees

- Minutes saved per effort

- Total minutes saved

- Total hours saved

- Estimated average hourly rate

- Estimated labor savings per pay period

A more complex approach would include cost savings expected from improvements in lower labor spending, such as overtime, premium pay, agency or contract labor, or savings from improved attendance or reduced benefit costs. However, these types of savings estimates require a much more thorough understanding of policy, occurrence, and technology and the specific organization's data. These detailed assessments avoid taking general areas of savings, such as overtime and projecting savings, out of context or without understanding the root cause. For smaller organizations, the cost of such an estimation effort may be prohibitive.

(d) Calculation Tables

A simple calculation table using the categories and factors shown earlier can be used to complete the savings estimate. Note that each category will have a separate table with results that will be added to create a total. Example numbers are shown in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1 Example Limited ROI Calculation Table

| Individual Category—Data Entry | Weekly Pay Period |

| Factors | Estimates |

| Number of employees | 100 |

| Minutes saved per effort | 6 minutes |

| Total minutes saved (100 employees x 6 minutes) | 600 minutes |

| Total hours saved (600 minutes = 10 hours) | 10 hours |

| Estimated average hourly rate | |

| (An average rate can be used) | $25 |

| Estimated labor savings per pay period | |

| ($25 × 10 hours) | $250 |

| Number of pay periods per month | 4 |

| Total amount of savings per month | $1,000 |

| Total Category Savings | |

| Factors | Estimates ($/month) |

| Data entry | 1,000 |

| Reduced human error | 250 |

| Reporting | 200 |

| Auditing | 50 |

| Time reporting | 125 |

| Leave reporting | 25 |

| Lost time | 300 |

| Scheduling | 150 |

| Total savings per month | 2,100 |

| Total savings per year | 25,200 |

| Cost of WFM System | |

| Total cost of WFM system | 12,500 |

| Savings per year | 25,200 |

| Payback (12,500/25,200) | 5 Years |

| ROI in two years (25,200 × 2 = 50,400 — 12,500) | 37,900 |

Behind each of the factors in Table 3.1 is a metric and a simple calculation of the savings per item and the number of occurrences per month. The sample calculations shown are only to demonstrate the formula to provide the answer to the basic question: Will the proposed WFM system pay for itself? Again, the recommendation is to complete a detailed ROI analysis on any major purchase. However, the ballpark approach does provide some simple answers, especially about moving forward with a purchase or modification.

(e) ROI for All Organizations—Scalability and Due Diligence

As discussed earlier, scalability and due diligence are also linked to the process of developing an ROI. There are many excuses for not calculating ROI and doing the associated work that goes along with it. These excuses include: We are only a small shop, so we do not need to do it; We do not have time to do it; We do not have the expertise to do it; We have a good gut feel and are experienced so we do not have to do it; and many more. Common excuses for not going through the processes to select and purchase the appropriate system that fits the requirements and budget of a company are related to “We just do not feel like doing it.” If the reason for not going through the process is actually “We do not know how to do it” then there are independent consultants and contractors available in the marketplace who can be hired for short-term engagements to help with the process.

All processes that are discussed in this and other related chapters are scalable based on the size of the company, the requirements, and the expected budget. The developed documentation will not be the same for each company. A small company may have less documentation because their requirements and operations environment are small. A large corporation may have substantial documentations due to complex hardware, software, and operational environments.

When debating whether to do the ROI effort, remember that making the effort to fully analyze the workforce's needs and the impact of a WFM system on current operations will reduce the project's risk by preventing the purchase or investment in an inappropriate or overly expensive system that is not needed. When a company's individual culture, size, work process, risk acceptance, and current and future state is taken into consideration, the actual selection of a vendor and system is generally more in line with business and cost expectations. And, making the effort to determine ROI up front demonstrates that those responsible for the selection have used a due diligence process to protect their company, the investors, and themselves from an expensive mistake.

(f) Involving the Appropriate Persons

As with most projects, one of the key steps to success is making sure that the appropriate persons are involved in developing the ROI. This is especially true with finance. Although many other projects and system areas can be learned quickly, this approach should not be used with finance or with calculating the cost of a WFM system and the return on investment. Each organization should use a trained and experienced finance representative to help calculate and verify that the cost and return estimates are complete. Most large companies have a chief finance officer or a finance representative who can direct the approach and information development to make the calculations. If a company does not have a financial person they should use an independent certified public accountant with experience in calculating ROI for projects.

Project managers, business analysts, department heads, and project sponsors should be involved and support the development of ROI. Subject matter advisors likely also contribute to the development of ROI by combining their experiences with the current system and the processes and identifying gaps that may increase legal or cost exposure. However, the persons who should manage and control these calculations are the financial specialists in the company. These persons are typically in the finance and accounting departments who have the skills and experience to perform the ROI calculations and determine what, where, and how the assembled financial numbers need to be used.

It is important that the assessment of ROI be objective and supported by facts. An independent consultant can help to achieve that. Further reasons why others should not have control of the ROI financial calculation include assumed minimal experience in completing these calculations and a perception of biased opinion on implementing the system that is not based on financial considerations. The important project members should be involved and be heavily familiar with the financial information provided to the financial advisor to complete the ROI calculations. However, they need to allow the finance specialist to lead the work of detailed calculations.

Other persons who should not be relied on as the sole source of final ROI information are vendors who provide products or services. They will not know the organizational planning for the investment, internal processes, and infrastructure and the actual goals and requirements of the company. Because they lack full insight into the buyer's situation, vendor estimates may be overly optimistic or may not consider costs that are not readily apparent or long term. While most vendors are honest with the intent of helping an organization complete calculations, they still have a vested interest in making the sale. Should something go wrong, their calculations will be scrutinized as being misleading or inaccurate. For both the organization purchasing a system and the vendor selling the system it is recommended that someone objective and internal at the company complete and assess the ROI calculations.

With vendors in mind, many have samples of ROI tables and calculations that are provided to help customers do their assessments and ROI. These samples should only be considered as samples and not a cookie cutter to do the ROI calculations. These generic ROI samples have limited cost and benefit information and are an average view that may vary widely from what a company may actually have when doing an ROI assessment. However, as a company does develop the estimated ROI it is beneficial to allow the prospective vendor to examine the financial estimates for feedback and an external perspective. It helps the vendor gauge whether the expectations for an ROI are overly optimistic for the type of system being implemented and assist with adjusting the expectations before the system is implemented.

(g) Planning and Identifying Company Goals

Before any steps are taken to select or acquire a workforce management system, a WAM-Pro should review previously defined goals, plan to identify and assess the new company goals, evaluate the actual need for a system, define budget status and available funds, and determine the high-level benefits to the company. If these plans do not exist, this effort can be executed by an assigned business analyst as a project management activity.

The questions and directives that the business analyst will help answer include: Does executive management feel that there is a need for a workforce management system or do they feel that they can purchase and implement the system at the current time or in the future? And: If the system is proposed does it fit existing strategic planning? If the answer is yes, then the project to move toward a WFM system is likely to be accepted. If the answer is no, then significant work needs to occur to explain the need for the WFM system, as well as to determine high-level estimated costs and highlight impacts on the business environment if the system is not implemented.

If the goal is to have a WFM system implemented, then the efforts will go toward a detailed plan with cost estimates and ROI expectations. If the goal does not have a workforce system included, then the focus will be on providing information to executive management demonstrating the need and benefits of a WFM system to the organization.

Addressing organization goals is paramount. Some workforce management system implementations fail because executive management does not fully support or understand the importance, impacts, and potential cost and financial returns associated with the implementation. If there is a lack of understanding there will be fuzzy or unrealistic expectations with the benefits and ROI. This in turn may lead to canceled implementations or modifications of the implementation where the usage of the system becomes inadequate and does not meet the needs of the organization.

(h) Requirements and Solutions Verification

One of the most tedious efforts for any project is the development of requirements to meet the mission, goals, and needs of the organization. These requirements should consider the business, cultural, technical, and financial issues. The requirements are defined and documented in the analysis phase of the project by the business analyst assigned to the project. Determination of the requirements takes time, requires organizational agreement, and needs to be documented. With WFM systems, defining the requirements is highly important due to the variability of timekeeping, reporting, and analysis that occurs with companies.

An ROI determination ultimately begins with requirements. The requirements lead directly to the appropriate solution. The appropriate solution leads to a development of the total cost of ownership and identification of the source of financing, in effect, whether it will be funded internally or externally. The cost assessed against the financial benefits will lead to the ROI.

The reader may ask why this write-up about requirements has been placed in the ROI section. The answer is that appropriate requirements should be assembled and used to calculate the ROI, or else the calculations are only a rough guess with minimal validity. Unfortunately some projects get off track at the beginning because the requirements are poorly defined or unrealistic. This is especially true with WFM systems. It is imperative that a formal process is used, as defined in other sections of the Workforce Asset Management Book of Knowledge (WAMBOK), to determine the requirements. This process should be done with internal resources and unbiased external consulting assistance if needed.

One common debate by employers is when to bring in the product vendor to participate in requirements gathering. The financial analysis process should precede any introduction of a vendor into the process because by its nature, the financial analysis is an assessment of fundamental project feasibility. The outcome may be that the time is not right for a technology investment or the funds are so limited that certain product solutions simply will not be a good match. In fairness to the vendors, who will invest considerable time and energy into helping the employer, their participation in requirements gathering is better done when the organization is ready to commit to an investment and understands which vendors may qualify based on the early financial picture. The initial financial analysis will keep the organization focused on the projected financial returns that are driving its selection. When vendors participate at the right time, they will be less likely to drive employers toward features and functions that over- or undersupport those objectives. Vendors will be less likely to waste time and effort with a client if a new WFM system is not currently feasible. This is a win-win because both employer (buyer) and vendor (seller) will be aligned around product requirements and financial benefit in a way that will support the eventual pricing and product selection.

Overall an organization should do an independent analysis to determine requirements and approaches to address the needs of the organization. If the company opinion is that vendors will be needed to research what is available in the marketplace, then other approaches at research are needed to identify the approaches, solutions, and potential vendors. If there are no resources inside the company, then an independent professional business analyst with experience with a workforce management background should be engaged.

The requirements determination process includes:

- Creating and defining a problem statement that lists functions and capabilities that are lacking in the organization and current workforce system or existing processes.

- Determining the processes and features that work effectively with the existing system whether manual or automated so they are included in a new system.

- Determining the features and functions that are needed to address the problems, goals, and requirements of the organization.

- Assembling the above into a requirements document that is used to research and locate a vendor and product or service that will address the defined requirement. The requirements document is used in a request for proposal or checklist when negotiating with the vendor.

- The requirements definition is essential to determining the size, scope, and cost for the WFM solution. This forms the investment side of the equation. Scope items that may arise later in the process should be assessed against this initial slate of requirements, on which the business case for ROI was built. If the scope is allowed to creep outside the original requirements, then costs naturally rise, detracting from the originally estimated ROI.

- To establish the credibility of the ROI assumptions, requirements should be clearly defined and stated up front along with the expected return to the company from implementing the slate of requirements.

By having the requirements developed and documented in the manner listed the organization will be able to develop the ROI information. The ROI statement should include:

- Identifying and financially categorizing the benefits received from the requirements.

- Selecting a potential vendor, solution, and associated costs.

- Being able to allocate costs on specific areas of the requirements solution.

- Having features and requirements defined so they can be reduced or expanded as needed.

- Having formal documented requirements and calculations that can be compared during audits to show that the organization has used due diligence to select and purchase the appropriate system.

(i) Expenditure and Investment Return Expectations

The finance personnel in organizations should have information related to expenditure and investment return expectations. Most organizations will have internal and external financial information that is used to assist with decisions related to investing in projects and systems. The decision criteria should be based on what the organization considers to be reasonable costs and no less than minimal returns. If the cost is higher than what is considered reasonable, then it will most likely not be approved. If the investment return is under the minimal amount, then the project will also likely not be approved. Some examples of this type of information include:

- External versus internal investments. Companies will usually invest some of their profits in external investments. These investments are in generally noncompeting, different industry investments or through some form of pooled institutional type investments where an investment firm invests in a portfolio of trusted companies. For these types of investments there will be a set expectation on the return. For instance, depending on the risk factors the return expectation for a company may be as low as 3 percent or as high as 12 percent. When companies do have a reliable external investment expectation they will usually expect that internal investments, like a WFM system, match or be higher than the external investment return.

- Project portfolio. Within companies there are usually lists of projects that will require funding. These projects may be strategic by producing new products or tactics for doing business or they may be operational where the focus is on repair, maintenance, upgrade, or regulatory. Each project is listed in a portfolio that identifies the criticality, soft benefits, and financial benefits. The projects are then examined from various perspectives that show expected costs and returns. The selection process will consider a variety of issues, which does include total cost. If a project costs more than a company has in reserve to pay for the project it may not be approved even if the return on the investment is high. In addition, if the company needs the project to move forward in business it may need to borrow money that will need to be paid back. If the amount and cost of borrowing is considered outside the bounds, and the organization's finance authorities have determined the project may be scaled back, a different solution may be chosen, or the project will not be approved.

Based on the outcomes of assessing the financial impacts, a project may or may not be approved. Some companies with similar assessment results may approve a project while others will reject it. The difference is the expectations that companies have set according to their own financial conditions, products, market share, and projections.

There are no set standard criteria for expectation, as each company develops its own. This is part of doing business and what makes some companies successful while others are not. The development of the financial return expectation will generally follow ratios of investment to return. Ratios do not represent actual amounts of cost, only a percentage in the form of a ratio. For instance, a cost to return of $25 to $100 is a ratio of 1 to 4. A cost to return ratio of $25,000 to $100,000 is also a ratio of 1 to 4.

There are finance books available that do provide formulas to calculate financial return. Because finance books rarely take all issues into consideration for the decision, many companies use the external investment return as a basis for deciding on an investment.

Many companies face a dilemma about how to determine their actual investment expectation. The financial assessment uses a battery of calculations to assist with that determination, including: the net present value, modified internal rate of return (MIRR), payback period, hurdles rates, and borrowing rates. This is why it is important to have the financial authorities of a company manage the actual calculation using the information provided by those developing the project.

Expenditure levels are generally based on the current financial standing of the organization. If the company is profitable there will probably be money available for projects. If the company is not profitable there will be little funding available. The estimated ROI will do no good if there is no money available to fund a project. In many cases, the current financial standing will lead to an extrapolation that takes the current financial status into consideration for a long-term financial projection. Again, the better or worse the projection the more the organization will or will not spend on a project.

Usually a company will generally have a pool of funds from profits or reserves that are used to maintain current operations, budgets for future operations, and for selecting projects that bring the most benefit to the organization. The existing money is spread across a range of projects selected for their benefit to the organization. The à la carte approach means that often many smaller projects with lower costs are selected over a single project with higher costs. With this in mind, realize that any money approved for a project will go through a competitive analysis before it is allocated. The impact of this is that unless you know and understand the estimated project costs that are derived from requirements and vendor information you will not be able to compete for any available funds.

Within a single domain of business need, such as WFM, there may be small project requests that need to be evaluated for ROI and proper prioritization. The workforce management office is designed to begin the evaluation process and help sequence such requests.

After the requirements for the WFM system have been determined and the budget for the project has been approved, the search for a solution begins. The formal documentation created for the business case can be used to request a proposal or quote from a vendor. The solution provided by a vendor should match the requirements. The solution should have an identifiable cost for the delivery and implementation, such that the requirements are equal to the cost. If verified ROI is needed for funding the project, that will become an additional requirement.

(j) Assembling Cost Information

The assembly of cost information to make the ROI determination requires a team effort and collaboration between project team members internal to the company and the external vendor(s). A realistic ROI cannot be determined until after the requirements have been defined. ROI may be one of these requirements. To meet the requirement for ROI, a solution that meets the requirements should be selected. The solution and implementation will determine the costs. Therefore, the vendor will participate as a member of the team to specify the costs of the solution being proposed. Internally, project participants will need to assemble the activities, costs, and financial impacts (both positive and negative) that are due to the vendor solution implementation.

It should be noted that the solution quote or costs from the vendor should be exacting. Do not assume that any other related products or services are included unless they are documented in the proposal or quote. Also, undefined or unlimited costs that cannot be specified must be taken into consideration and have limitations and approvals associated with those items. It is common for implementations to have undefined time and material services attached to the project that can substantially inflate the overall cost above what was initially estimated. This inflation causes a gap between the original cost estimate and ROI and what actually occurs.

If requirements are not properly defined or documented in a manner that adequately identifies what is needed, there may be gaps in the original vendor agreement and what is needed on delivery. Gap costs are a major issue when it comes to realizing a planned ROI. The WAM-Pro can help elicit the business requirements. However, the information provided to the WAM-Pro will only be as good as the participants in the requirements gathering sessions. For this reason, once a vendor is engaged, it is recommended to carefully review and evaluate the requirements and costs again with the original participants (stakeholders, project team leaders, subject matter advisors) and with the vendor. This helps to map the requirements to the new (proposed) solution and identify potential changes.

Once the project team has done its best to close or record potential gaps, then the cost information should be assembled for management review and approval. Cost information can be organized in a variety of categories. It should be up to the organization's financial representatives to determine the categories and how they will be assessed. Some of these categories include:

- Hardware and office equipment purchases.

- Operating systems and software purchases.

- Custom reports and interfaces.

- Networking and telecommunications purchases.

- Consulting services.

- Project planning efforts.

- Communications and phone costs.

- Facility costs related to the purchases.

- Associated implementation costs for any purchases.

- Warranty costs for any purchases.

- Training materials and related costs.

- Internal manpower costs directly associated with the project.

- Contractor and temporary manpower hiring.

- General and administrative costs that can be allocated to the project.

- Taxes and interest.

- Vendor ancillary costs related to travel, lodging, food, and materials.

Although there may be other categories, these are the common ones that can occur with the implementation of the WFM systems.

Table 3.2 shows a summary listing of cost items for a project. Notice that there may be some expensed items as well as capital items that will become an asset for depreciation. Regardless of how the financial area of a company classifies an item, each will need to be listed as a project cost. Where items will be expensed, it may be useful to have the number of years over which the capital cost will be expensed.

Table 3.2 Sample Summary Project Cost Table

(k) Assembling Financial Benefits Information

The assembly of benefits information to do an ROI for the implementation of a WFM system can also be a challenge. Quite often those involved with assembling benefits collect intangible or unquantifiable items that do not provide a calculable metric that can be used to determine an ROI. Some of the intangible benefits include making things easier or more organized, raising morale, good public relations, replacing a system that is being sunsetted (allowed to go obsolete and then discontinued), improved reporting, having more control on things, and so forth. Although these items are important, if they are real they should be able to be converted into some type of metrics that can be used for the ROI.

Generally, benefits received from the implementation of the workforce management system need to be extrapolated from reports or time studies and converted into some type of metric. When looking for benefits, examine important areas such as time-saving process improvements, reducing or shifting of manpower, increasing productivity or retention, reducing employer obligations such as taxes and benefits, identifying and addressing payroll leakage.

To determine the benefit value of time saved with WFM solutions, time motion techniques can be used to do a comparison of the existing method or system versus the planned system. The time saved can be multiplied by using an average hourly rate to determine the actual savings or return. If this is applied to multiple people in the organization it can be a substantial sum. Time saved may create a reduced need for people such as contracted or agency help, temporary workers, or other types of nonemployee help.

Differences in administrative costs between the use of different systems or methods contribute to the benefits case. If a manual method in use requires three people, and a new system reduces manpower to one, the saving is in salaries and is easy to determine. Although the cost savings related to manpower is relative in that most of the manpower time being saved is usually shifted to other company areas (that is, the timekeeping business area may have reduced cost but the organization as a whole does not), the reallocation of human resources to more bottom-line impacting areas benefits the company.

A primary area of WFM benefits is related to the automated tracking of time and the analysis of the time being used by employees working and receiving pay. Often the use of the WFM system is limited to payroll and detailed analysis of the information does not occur. Due to a lack of awareness or training, the timekeeping information is not fully applied to business issues related to payroll leakage and operations inefficiencies.

One of the more useful benefits from the WFM system is the ability to identify compensation and scheduling problems and then come up with impactful solutions on how to reduce excess cost. Too often, current timekeeping systems focus only on meeting payroll requirements. But there is a shift in business today that requires organizations to manage the entire cost spectrum more effectively. The difficulty in converting this to a financial benefit is that accurate numbers are often not available and they have to be researched or developed. This means that to identify realistic cost savings, previous payroll and timekeeping information will need to be collected, analyzed, and then extrapolated into cost savings. If this is not feasible to do internally, outside consultants can perform an assessment or provide benchmark information available related to this research. Vendors who have done extensive research may have independent studies that they use to assist them with saving estimates that can be used. However, the preferred analysis is one conducted on the unique data of the specific employer as it cannot be known how closely average benchmarks and case studies apply.

Another area of financial benefit or cost is how the implementation impacts the assets of the company. Assets are the company worth. The acquisition of a system and the value of that system may increase the assets or value of the company depending on how the implementation items are categorized as capital or expense items.

How the new WFM system and the components are to be categorized can be complicated and will be based on documented rationale by the organizations' finance and accounting areas. The rationale usually comes from guidelines provided by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA). Due to issues related to software, statements of positions (SOPs) have been issued on how to account for software purchases and software developments.

An example of this is SOP 98–1 Accounting for the Costs of Computer Software Developed or Obtained for Internal Use. This guideline as well as other accounting guidelines will be used by the organization to determine what will become an asset and what will become an expense. This determination may directly impact the ROI calculations by having some items involved in the WFM acquisition capitalized while others are expensed.

The finance, accounting departments, and associated public accounting firms are familiar with the finance and accounting regulatory guidelines and should be able to take the rules into account to assist with the ROI calculations. Due to the complexity and regulatory responsibilities that accompany these decisions, the determinations need to be made by those with the appropriate authority in the company as outlined by the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002.

The assembly of financial benefits information is critical for the approval of a WFM system implementation. Without these numbers the ROI calculations cannot be made.

(l) Creating a Model to Calculate Investment Returns

ROI for a project is not a single calculation, but is instead a group of calculations and financial perspectives used to make a decision as to whether the project is worthwhile for the organization. An example of an ROI model may include the following calculations, which are nothing more than final results used to make the decision to move forward with the project:

- Payback period (PBP). Indicates how long it will take to recover the cost.

- Net present value (NPV). Focuses on the gains of the deliverable over the lifetime of the solution (software, hardware, etc.).

- Modified internal rate of return (MIRR). Focuses on the rate of return of the deliverable over the lifetime.

- Hurdle rate. Indicates whether the returns will be above the financial expectations of the organization.

- Return on investment (ROI). Indicates the expected amount of return in the short- and long-term period of the project deliverable.

Some of the other calculations listed later are used to assist with calculations that feed into the above model.

(m) Financial Formulas and Calculations Related to the ROI

There are a variety of formulas and calculations used to determine the ROI for a project. They provide different views and perspectives for an ROI assessment and decision to approve the expenditures for the project. When examining the formulas, recognize that there are numerous versions of the same format that can be used to derive the final calculation. Familiarity with the various formats is needed to do manual calculations. Nevertheless, it is recommended that automated financial software be used to make the calculations. Some of the most common components or calculations and a high-level definition for each follow.

Note: The formulas for the various calculations follow. The purpose of showing the formulas is to emphasize the complexity of the calculations and to get acquainted with the terms, processes, and tools used to determine value from a financial perspective. It is not expected that the actual formula be executed by the WAM incumbent. It is important to be aware of the calculation and how it is used. There are software applications and online Excel calculators used to make the actual calculations. In most cases, company financial advisors will do the calculations and may even modify them based on defined variables from the organization. Again, it is helpful to understand the definition and understand why each ROI calculation and components are important. It is also important to remember that if bad or inaccurate information is used, calculated results for a ROI are worthless. Let us start with an understanding of the components of ROI:

- Capital. Capital is the assets owned by the business. This may include collection device, computers, phones, tools, equipment, IT, hardware or software that is owned outright, goods for sale, and so on.

- Cost of capital. The cost of capital considers the cost of debt and equity (value taken from the company in a project). It is primarily concerned with the expenses incurred in borrowing money, accepting external investments, and using internal funds that could have been used on another project. The cost of capital is a comparison formula used to determine if another project would be a better investment by requiring fewer funds to gain the same level of benefits. An example of this may be contracting a vendor that provides or hosts WFM solutions rather than purchasing a WFM system. For example, some companies may find use of WFM services is lower than the investment and return on purchasing a WFM system. So, the cost would be much lower while still obtaining desired benefits. In this case, the service was selected because the cost was lower and brought the same value. The purchase would have provided the benefit, but would have cost the company more money. The cost of capital was higher with the purchase than with the service.

Note: When considering the financial benefits of SaaS or hosted solutions, the same calculations used for the lease as purchase can be used. There are some differences between purchase and lease items in the detail information. However, the costing totals for each are still used in the calculation. As long as the depreciation time period for the purchase is used for the lease, the calculations for comparison will be valid. What can be challenging is how to quantify the intangibles of ownership from purchasing versus the reduction of direct costs from lease or subscription. - Discounted cash flow (DCF). Cash flow is simply the movement of money into and out of an entity. The money in is the cash received by a company; the money out is the cash being spent on expenses. The entity is the company. The DCF is the calculation used to determine the adjusted value of a future cash flow as if they were current. Money in the future is generally more valuable. If the DCF shows that the value of the future money is higher than the current cost of the investment, it is considered beneficial.

The final result is the sum of each individual calculation for the financial periods being examined. In the formula, CF stands for the cash flow. The subscript with each CF is the financial period being calculated. The r is the discount rate or interest percentage. The superscript is the time period used for each calculation. The n stands for number of periods. The DCF computation will be in dollars. The formula for a DCF model is:

- Depreciation period (DP). The DP is the allocation of the cost of an asset, like a WFM system, spread over a period of time considered to be the useful life. Or, in plain words, the total value of the investment has a set amount deducted monthly until the value of the asset reaches zero in the company's accounting records. Other terms for the same calculation may include amortization schedule or depreciation schedule, solution, or expense.

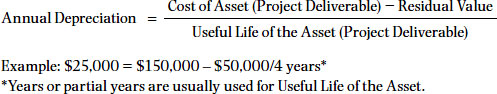

The depreciation schedule may use a straight line method or a declining balance solution depending on the organization's finance approach. Determining the depreciation tells the organization how long the purchased item will take to be reduced in value to zero. The DP calculation is used as a metric in decision making for the project. If the depreciation time is shorter than the time it takes to reach the expected return on investment it may indicate that the purchase is not a good investment. The annual depreciation will show the amount depreciated for each year. The number of years for the useful life of the asset is usually determined by standard accounting rules. The formula for depreciation is:

- Future value (FV). The FV calculation determines what the value of a current asset or money will be in a future time period. This determination often helps to decide whether a project should occur now or in the future. It also shows what the money being spent now will be worth in the future. In the formula shown below, the FV stands for future value. The PV is present value. The r is per annum interest rate and the t is for time in years.

The formula for FV is:

- Hurdle rate. The hurdle rate is the minimum expected return from an investment. These rates may vary based on risk, borrowing rates, length of project, lifetime of system, and other factors identified by the financial area of the company. If the project does not have a return higher than the hurdle rate it will likely not be approved. Financial authorities for each company will determine their hurdle rate based on their financial conditions and projections. There may also be different hurdle rates based on whether the project is strategic or operational.

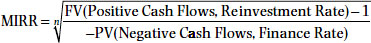

- Modified internal rate of return (MIRR). There are two rates of return calculations, the internal rate of return (IRR) and the MIRR. The IRR takes the discount rate used with the net present value of cash flows from a project equal to zero. The second calculation is the MIRR. Although the IRR calculates the cash flows as reinvested at the IRR, the modified MIRR calculates that positive cash flows are reinvested at the organization's cost of capital used for financing the project. MIRR provides a more accurate cost and profitability of a project. The higher the internal rate of return the more likely the project will be approved. The MIRR calculations state that the positive cash flow achieved from the investment is then used by the organization for other activities at the same rate as if they borrowed the money. For the formula the FV stands for future value, PV stands for present value, n stands for number of periods, and the overall calculation uses a square root derivative. The formula for MIRR is:

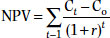

- Net present value (NPV). The NPV is the difference between the present value of the current cash inflows and the present value of current cash outflows. The NPV will also take into consideration future cash flows. The purpose of the NPV is to determine if and what the profitability is for a proposed project or investment. Project implementation is an investment for the company. NPVs are an important decision factor when there are projects that will require capital budgeting and impacts on the overall company assets. For the formula the ∑ stands for sum of the total, the C stands for cash flow, the subscript t stands for time, and the r is the rate. The formula for NPV is:

- Payback period (PBP). The PBP is the amount of time it will take to recover the total cost of the initial and recurring costs from the investment. The shorter the payback period the better the investment. The formula for PBP is:

- Return on investment (ROI). ROI is a calculation that estimates what the business receives of value as the result of an investment in a project or other asset being purchased or implemented for a company. The ROI is compared to other projects and investments to prioritize or select. The return is divided by the cost and then usually shown as a ratio but can be shown as dollars. If the ratio is not positive the proposed investment is usually not approved. The formula for ROI is:

(n) Calculations and Decisions

The information that is developed for costs and savings are fed into the selected financial assessment model, and calculations are used to determine ROI based on appropriate information from the company and the problems being addressed. The model is a grouping of selected formulas that give financial perspectives to show pertinent financial impacts, pros, and cons that the system implementation will have on the organization. The formulas are based on the calculation components listed previously. The components included in the calculations will provide the information to create multiple perspectives related to the financial benefits associated with the implementation of the workforce system. Included in the calculations will be tables with multiple years that usually go beyond the payback and depreciation periods.

Although purchasing cost information may be easier to develop, there is a tendency to leave out items that can become significant over time. There is also a tendency to inflate the cost benefits and value that a new system will bring to the organization. Care and realism are needed to produce an accurate depiction of what the return on investment will be to a company.

Ultimately the decision to purchase a WFM system comes down to the ROI. Demonstrating a strong ROI above the hurdle rate increases the chances that the system will be approved.

Assembly of the final calculations that will assist with the selection of a WFM solution is demonstrated in Table 3.3. This is a sample of how final calculations can be assembled to assist with the selection of the appropriate project solution. In this example, Projesct/Solution 1 is the choice. In this case the NPV is the highest of the three choices. The MIRR (17.59 percent) is greater than the cost of capital (15 percent) with an 18 percent hurdle. It has the highest overall return of the three options, and the ROI is higher than the cost of the project.

Table 3.3 Sample Decision Table

Project/Solution 2 was second in the selection because it had lower numbers than Project/Solution 1. Project/Solution 3 was not chosen because it had the lowest financial return and it did not make the hurdle rate.

Table 3.3 is only a sample of the type of chart that is used to assist with project selection. Different organizations will use different style tables and select the calculations that they feel are the most appropriate for their company and their use cases. The table enables management to get a quick look at a summary of the final results of calculations. For this reason, it is critical that the processes for gathering requirements and calculating cost and benefits be controlled, independently reviewed, and as accurate as possible. If the information used to make the calculation is flawed, the table with the financial information will also be flawed.

(o) Tracking and Assessing the Short- and Long-Term Outcomes

So, what happens to the ROI assessment assuming that your project is approved and is implemented? The ROI expectations form the basis for metrics, key performance indicators (KPIs) of the success of the implementation. Tracking subsequent performance of an implemented new process and system is an activity that many companies avoid or simply do not do. However, it is a critical step to make certain that the solution is meeting your original goals and to understand where some tweaking of a process or a system may be necessary to further improve ROI. Management will be acutely aware if the solution has issues, higher than anticipated costs, or does not seem to be achieving what was promised in the business case. The WAM-Pro and the WMO have a responsibility to stakeholders, investors, board of directors, executive management, and owners of the company who accepted the investment into the WFM system based on financial returns. In particular, the system may need to pass an audit by internal and/or external auditors especially with publicly held companies, who examine the accounting information and expenditures to determine that financial malfeasance has not occurred. The metrics or tracking information should be assessed throughout the life of the system. Again, it will likely take financial knowledge to determine if the value the system was what was expected. It will also take the active engagement of those managing the processes and systems to provide constant feedback and to execute system reports that demonstrate the performance from the same angles that were included in the business benefits case. In other words, are your proposed benefits being achieved?

Many small companies feel that the tracking and assessing are a burden. However, the actual purchase was based on scale. In general, the smaller the company, the smaller the purchase; the larger the company, the larger the purchase. So, tracking should follow the same pattern and be scalable. Although smaller companies may not have a board of directors, they may still have investors or owners who will be interested in the profits or losses of the company. Even if the company is owned by one person with no other persons involved, decision tracking is important.

The other aspect about smaller companies that causes concern is who does the financials tracking and assessment. Small company employees wear many hats and often do not have the time to track and assess. Unfortunately time needs to be made, as it is part of business survival. However, when dealing with the financial aspects companies can use their accounting firms to assist with the assessments as part of their yearly tax process. Although a small company may not be interested in the details of financial success, the IRS will want to know about the investments, tax write-offs, asset shifts, and company value.

Overall, the tracking and assessment process is not difficult to do if original costs and financial benefits were identified and documented in a manner that produces realistic metrics. The same information used during the approval process will be used for the tracking and assessment. There will also need to be calculation decisions for when financial benefits are no longer counted, when newly discovered benefits are added, and when business and technical environment changes may invalidate the old models so new ones need to be developed. This tracking effort is well suited for assignment to the workforce management office (see Chapter 2, Section 2.3).

(p) Capital Budgeting Process

A question commonly asked during project planning is when do the calculations need to occur and when are they presented to management. In general the sequence of events to presenting the project financial estimates are:

- Requirements are defined and given to vendors for solutions and costs.

- Cost items for the project are identified or estimated.

- Financial returns for the project are estimated.

- ROI is calculated.

- Findings for the projects are then presented during the yearly capital budgeting process to select and approve projects.

- Findings may be presented at a special capital budgeting meeting that focuses on single projects at any time during the year.

The capital budgeting effort is usually a yearly event where the organization lists and then determines which requested projects, such as the implementation of a WFM system, is profitable in the long term and worth pursuing. Cash inflows and outflow are analyzed to provide a baseline expectation for financial return. Requested projects and investments are prioritized by profitability and business need. Those at the top of the list are approved and those less profit are approved based on remaining funds. Those that are not profitable or do not meet the minimal financial return expectations are not approved.

It is important to be aware of the capital budgeting process and schedule that occurs. WFM project assessments should be started early enough to be able to meet the deadlines for the process or the project may have to wait until the following year's capital budget process.

(q) ROI: The Multistep Process

When people talk about ROI they often think of one calculation to define return on investment. However, there are usually many calculations and results that are developed to provide multiple perspectives and that assist with making the decision to purchase a workforce management system. The formation of the calculations begins with the defined requirements that help identify a solution. The solution is priced by the vendor. Other financial costs and impacts are identified and quantified by the company that wants to implement the system. This generated information is then fed into the calculations that provide the final information as to whether the implementation is worth the investment. Ultimately, an ROI analysis should tell the organization whether they should purchase the workforce management system and whether to continue to support or enhance it on an ongoing basis.

(r) ROI Process Flow

The WAM-Pro may find the following process effective for developing ROI for a workforce management system. The flow is based on good business practices found in formal project management and business analysis.

- Identify and engage the appropriate staff for the project.

- Determine company goals.

- Identify and document requirements.

- Research marketplace solutions.

- Invite vendors to compare their solutions with requirements.

- Determine the costs associated with the vendor solution.

- Determine the financial returns or savings associated with the vendor solution.

- Feed the costs and returns information into the ROI model established by the company.

- Complete the ROI model calculations.

- Compare the ROI calculations against the company financial expectations.

- Adjust or accept purchase.

- Schedule and execute recurring ROI validations.

Note: The ROI process flow will vary from company to company. The previous list is a composite average of what many companies do to determine their ROI. Additional steps may be added depending on the needs and policies of the individual company.

3.3 FINANCING WORKFORCE ASSET MANAGEMENT TECHNOLOGY7