CHAPTER FIVE

Workforce Management Devices and Functionality

IN THIS CHAPTER, A WIDE ARRAY of data collection and management tools are identified and their functionalities discussed. Today's workforce interacts with more technology than ever before; being able to wield the technology with prowess is increasingly vital to an organization's sustainability. This chapter introduces and briefly explains many of the biometric, mobile, and fixed devices in the market today. Yet more importantly, this chapter describes the methods and techniques of effectively managing these resources. The intention is to expand the organization's knowledge of what devices and functionality packages are available, and also to teach them what to expect and how to use what they already have. The more an organization can do with technology furthers their competitive advantage. This chapter, in effect, connects device functionality to return on investment (ROI).

- Anticipate the types of features that are often required within timecard modules and explain the processes that automated timecards facilitate.

- Define the various types of accruals and required pay rules and relate them to the Workforce Asset Management (WAM) system design.

- Understand the structural impact of automated workflows and how this shifts the responsibility of traditional roles.

- Recognize which types of data collection systems are better suited to which types of work models as well as general limitations to functionality.

- Explain the basic capabilities, potential benefits, and possible challenges associated with biometric and mobile resource management (MRM) devices on the current market.

- Develop methods and practices to mitigate common issues associated with biometrics and MRM systems.

5.1 TIMECARD FUNCTIONALITY

The timecard, or time record, is the focal point of workforce management (WFM) systems. It is simultaneously the repository, calculator, worksheet, notepad, reporting mechanism, and viewfinder for labor activity. This is where data comes into the system, is manipulated, reviewed, and moved to outside systems. The timecard is where employees and managers congregate to communicate about time worked. The timecard depends on inputs from collection devices, employees, managers, schedules, and payroll and human resources (HR) systems and personnel. Timecards depend on business rule setup in the pay rules, system access rule sets, user role design, interfaces, and WFM modules such as accruals, schedules, leave, and attendance. The Workforce Asset Management Professional (WAM-Pro) designs and monitors timecard activity to deliver high-integrity data to critical systems and operational areas and personnel such as to payroll, managers, compliance, reporting and business intelligence, staffing, finance, and product and customer satisfaction.

(a) Time Record Views

There are several common types of time record views, including the weekly or biweekly timecard view showing employee arrival and departure times and various details about where employees worked and what tasks or roles they fulfilled. This view is most like paper timesheets. Timecards can also be laid out to show durations or spans of work time without specific start and stop times visible. This project view is useful for professional service employees and people who work against project budgets or client accounts. It is sometimes used for exempt workers who do not punch in and out but merely report total time worked. Some systems use the first timecard view mentioned earlier, but limit the record to in and out times only, not computed amounts. These views are most often used when the hours are not computed inside the timekeeping system so that users do not get confused when actual payroll amounts differ. Another type of time report view is the calendar view. This view shows a larger set of time data—often a month at a time and can be color coded to reveal high level activity such as absences, total hours, or special comments. This view is helpful for audits, attendance reviews, and overall monitoring of work activity.

Timecards can be viewed via the computer, the collection device that is enabled with a display screen, smart phones, and handheld devices. However, granting access outside of employer systems such as via a home computer presents serious issues for consideration. How is confidential data protected? Who manages the network to these nonemployer systems? Is the time spent reviewing timecards on personal systems compensable and how can it be managed?

Timecards are used to make a number of business processes easier, more accurate, transparent, and efficient. Basically they are designed to allow the input and editing of work activity data, automate the calculation of time based on the data, allow managers or timekeepers to review and approve time, and facilitate the entry of corrections to present or historical time records. The timecard itself only reveals the calculations that are generated in the background of the system via the rules engine. Timecards may promptly update computed data when it is entered or require the user to save and process the data to improve system performance. Some systems allow users to do a trial calculation to make certain their entry produces the desired outcome. In this way their edits are not saved and tracked until they are final.

It is worth mentioning, too, that what users, particularly managers, are allowed to do to a timecard may not necessarily be the same for their own timecard. Different groups of users may have different rights as well. Exempt workers may be allowed to enter their own time off (e.g., vacation or sick) while hourly workers must depend on supervisors or timekeepers to do so. Professionals such as programmers may enter in their total hours worked, but store employees must use the time clock to report their arrival and departure times. The WAM-Pro considers each of these things when designing user access and functionality profiles.

All timecards do not have to be viewed daily; only those with exceptions such as missed punches and absences or special pays. However, they are certainly to be opened and reviewed weekly and at the end of the pay period for a careful review of the data for completeness and accuracy. WFM systems are increasingly designed to make exception management easier and keep records up to date. Errors in the timecard inhibit the system and user's ability to use timecard data to manage larger issues such as total time worked, overtime, attendance, staffing, and the like. Until exceptions and errors are fixed the data fed to notifications, reports, and analytics and even payroll is inaccurate and could be misleading. Timecards are the domain of the employee, a timekeeper, manager, and payroll. Although they have a close relationship to schedules, schedulers do not need the ability to edit timecards. Above the manager level, system users may want to use timecard data, but access should be restricted to viewing unless they are acting as the supervisor's proxy.

The WAM-Pro plans for timecard accessibility and efficiency by guiding the development of useful time record selection tools such as quick finds and filters. When managers need to look at time records they are generally focused on a specific set of tasks such as managing exceptions or approving records for payroll processing. Therefore, the manager needs to see what needs to be fixed and what is not ready for approval first. Designing the proper exceptions into pay rules, schedules, and timecards is crucial to achieving these efficiencies. Common exceptions include missing or unpaired punches, long breaks or shifts, short shifts, missed meal breaks, overtime, late or early arrivals, absences, and low or high total hours. These exceptions are aligned with policies and operational needs. Managers also need to be able to filter WFM data to locate employees who are on leave of absence or recently hired or terminated as these events often create problems or omissions in the timecard.

Timecards can be an easy portal to find out information about employees such as their job title, home department, pay rule assignment, or hours worked. The timekeeping system itself often houses more information such as phone number, availability, and supervisor name. This information, while not necessarily visible in the timecard, can be navigated to quickly when the WAM-Pro designs on-screen views of employee demographic data for this purpose. For example, it may be helpful to create links or display toggle buttons to allow the user to easily jump from one module to another to reference important information such as going back and forth between timecard and employee record.

Many supervisors and schedulers will want to compare timecards to schedules and vice versa. Some systems provide a snapshot of the week's schedule within the timecard view for easy reference. Others allow users to easily toggle back and forth between schedule and timecard. Timecard data may also be populated into schedule views to make scheduling easier.

Another important component of timecard review is the allocation of hours by location. Where the employee worked is important to properly attributing the cost of that labor to the business unit where the work was performed. Time can be allocated not only to a cost center but also to a project, client, or work order and these should be easily entered and visible in the timecard. Some employers split worker hours by percentage rather than by spans of time. Administrative assistants may be shared by two departments and thus have their weekly hours automatically divided based on a percent. Another way hours are allocated is via the schedule. When employees are assigned their shifts, the location, project, or other identifier can be assigned in the schedule. This way, when the employee clocks, in the system automatically transfers the hours to the appropriate accounting code and subsequently appears in the timecard.

Paper timesheets allowed almost unlimited capture of information from employees and managers. Comments about why something happened, adjustments, or who approved an exception were easily written right on the paper. Today's WFM timecards use comment features that append notes to data in the time record. A manager or employee can post a comment selected from a list of predefined terms to a punch time or transfer explaining what happened. Some systems also offer free-form text allowing users to type a short ad hoc description. The benefit of the predefined terms is that they become easily used for queries and tracking because they are consistent and limited. The WAM-Pro works to create a comment list that handles the important exceptions and events that the organization wants to capture while keeping the list manageable. Common terms listed in comment lists include illness, late-in-traffic, school meeting, travel day, clocking error, forgot to punch, inclement weather, bereavement, lost badge, meeting, doctor appointment, off-site training, approved overtime, missed meal approved, and flex time. These notes are time-stamped and serve to support audits and questions about time records or attendance.

(b) Timecard Edits and Entries

Employees will forget to punch and managers will make errors in the timecard. Basic functionality includes the ability to make corrections and adjustments in the present and past time records. Most systems track these changes in the audit trail. The WAM-Pro should make certain that the policies for timecard edits are clearly understood because of the serious consequences of noncompliant or unauthorized changes to employee time. Including this in recurring training, reminders on login screens when employees enter the system, and policy documents is an important practice. Many employers limit the ability to adjust prior period records to payroll personnel only. This prevents unauthorized or problematic entries to records, which have already been paid, and must synchronize with the proper payroll processing. For example, is an adjustment to a past timecard going to be included in the next cycle's paycheck or is a special off-cycle manual check going to be written? The timecard adjustment entry must be properly done to differentiate so that no under- or overpayments are made. Move amounts may be a feature that is available in the timekeeping system. However, the propensity of this feature to be misused should be carefully considered before turning on this capability for managers. Moving amounts from one pay code such as overtime to a lower paying pay code such as regular to manage overtime could be a serious violation of Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) regulations. Managers may also move amounts to defer cost to another business unit without proper authorization.

Supervisors of exempt employees use timecards to enter paid time off. Most exempt employees do not punch in and out or record their actual start and stop times. However, this trend is slowly changing as cultural barriers to punching diminish. The real-time capture from exempts can help with staffing, security, and proper reporting of time off. Also, there are few if any regulatory restrictions around requiring exempt employees to punch in and out so long as their salary status and compensation are maintained appropriately. Timekeeping systems can be configured to accommodate various forms of exempt punching, including one punch processes where the exempt worker only needs to report one time into the system each day.

Timecards can be populated with pay codes, comments, and allocations that may or may not flow to the payroll system. For example, managers may benefit from the system breaking overtime down into daily, weekly, unapproved, or holiday premium overtime. But these hours may roll up during the payroll export via the interface to payroll into a single wage-type overtime. Blended pay codes such as Overtime2 in the timekeeping system may be broken down into regular, Shift 2, and overtime premium hours for payroll purposes. Because of this the WAM-Pro is wise to maintain a pay code translation table that defines these conversions and preserves a record of how timecard entries change over time to support historical investigations and timecard troubleshooting as well as train new WFM system administrators. It is not uncommon for timekeeping systems to have dozens or even hundreds of pay codes the names of which are not easily decipherable without a translation tool.

(c) Timecard Reports

It goes without saying that timecard data will be used to generate reports throughout the organization. These reports can be built into the system and used by timekeeping users or supplied from data warehouse or business intelligence systems that upload timecard data and report it alongside other key business information. Some reports and systems need only the raw timecard data such as in and out times and other systems depend on the computed total hours that the timekeeping rules generate. WAM-Pros use their knowledge of the system to ask important questions about use of data so that the right data is passed outside the system. For example, if only raw punch data is needed, will it matter that the system will use rounded data to compute time and therefore produce potentially different total hours when compared to nonrounded time? Although both outcomes are accurate, if raw data is supplied without rounding and report users do not understand this difference, they may interpret the timekeeping system data as inaccurate and unreliable when they see differences from payroll and other reports.

WAM-Pros take their responsibilities seriously by instituting routine inspection of time records and system design for possible misuse. Having audit trail reports built into the system is helpful but their mere existence is not enough. The ability to demonstrate that audit trails are actively and routinely used to identify possible problems and take corrective action helps the employer defend any possible grievances about how time record data was handled.

(d) Advanced Timecard Functionality

Beyond these basic functions the timecard technology has evolved to provide for more advanced functionality. Later in this chapter automated workflow is described as allowing employee and supervisor to quickly and easily communicate changes that impact the timecard and schedule. Attestation is one of the latest developments in timecard functionality. The attestation feature was created in response to a growing need to record the employee's signoff of timecard data as a complete and accurate record of time worked. Attestation is typically designed to present a formal, electronic acknowledgment of the policy and regulation surrounding time reporting, reminding employee and employer that worked time must be reported, hours worked should not be suppressed or underreported under any circumstances, and employees know where to go if there are problems with their ability to report their time. The attestation feature also works to verify that employees were given the chance to take a meal break or voluntarily gave up their right in lieu of pay thereby helping to protect the employer from penalty for noncompliance on these issues and making certain that employees understand their rights.

Another advanced feature of timecards is multilevel approvals, allowing for more than one supervisor to review and approve the time record. There are also timecard analyzers, which provide a breakdown of how time was computed and which rules were engaged so that supervisors and employees can understand how complex pay rules and time were added up. This feature may reduce the amount of calls to the help desk as workers can see the methods used to count their hours on their own.

(e) Pay Rules

Timecards would be little more than basic spreadsheets without the underlying power of the pay rule engine inside each timekeeping system. Pay rules break down how time is counted and allocated to the proper pay code. There are several categories of rules, and without going into great detail on how to configure pay rules, this section provides a brief overview of some of the primary pay rule building blocks. Each timekeeping system has its own special way of putting pay rules together and this is not intended to describe any particular system or method of time computation. Some systems have more rules or greater flexibility in composing pay rules than others. Many rules use Boolean logic—If . . . Then . . . or qualifiers when x = y or when hours exceed—but can only handle a limited set of concurrent qualifiers before they become challenged to handle the highly complex conditions. The WAM-Pro takes inventory of pay policies, processing, time cycles, schedules, and data collection solutions to determine what systems can meet their pay rule and timecard requirements.

The following is a brief introduction to common pay rule criteria.

Some rules do not change for an employee week to week. These include the definition of the pay period, the delineation of the work day, the set of holidays the employer recognizes, what to do if a punch is missed, what to do if a timecard is not signed-off or if there are exceptions in the timecard, and how time is sequenced (count daily overtime before counting weekly overtime). To meet FLSA and regulatory requirements many of these rules must remain fixed.

Other rules are more variable and are specific to the job or the shift. Although overtime is a part of the FLSA rules, there are exceptions or an appropriate hierarchy of which overtime comes first. Pay is based on when the employee works, so there may be many zone rules that define how employees are paid by shift, by day, on weekends, or on holidays. The systems can treat hours worked during scheduled versus unscheduled shifts differently. Pay rules are often designed around combinations of rules—what happens when the employee qualifies for several different conditions for pay at the same time (e.g., working the evening, weekend shift on a holiday when in overtime).

Exception rules do not necessarily change time, but report variances in worker activity that are important to time and operations management. Exception rules can vary down to the employee, as with many rules, and it is common to find discrepancies among managers who create and enforce exception rules quite differently across the organization. The WAM-Pro works to understand which exceptions should be made standard, which should not be allowed, and which outliers are operationally important enough to be allowed.

Rounding rules are variable in that they may be different based on the type of worker. So long as the rule is applied consistently and not used to suppress time, workers on the shop floor may have their time rounded to the nearest quarter hour for each punch, but an office person may round the entire shift span. At the same shop, truck drivers may be paid minute to minute.

Depending on the state (state-specific details can be found in Chapter 7) the WAM-Pro knows that meals and breaks are handled differently. Some organizations are required to apply rules based on seniority or union contract and these require special rules for discreet groups of workers.

Pay policies dictate how some time computations work. A nurse who is training a new hire may earn preceptor pay for those shifts. This rule must be able to be applied when she arrives to work or attached to the schedule to generate a premium in the timecard for the hours worked for precepting.

In addition to pay rules there are rules designed to tell the clock how to handle employee inputs. Device rules dictate who can punch at certain time collection devices, when, and what type of data they can input. The rules tell the system how often to send updates to the clock, as well as how often to poll the clock and send the punch data collected back to the main database for viewing in the timecard. They can be used to restrict employees from clocking in too early or too late, or from using a device that is too far from their work station.

(f) Timecard Functionality beyond Straight Timekeeping

Time collection devices are a portal into the timecard. Increasingly they are used to collect and report more than just in and out punch times. Employees can report attendance at a meeting, training, or work activity that is eligible for a premium during that shift. Advanced devices allow users to enter in requests for time off, schedule changes, and viewing of their hours, last punch, and even messages to and from their supervisor. Some systems send notifications via the device about certifications that may be expiring or required training.

Managers need to know where work was performed and the integration with the accounting structure and codes facilitates the assignment of hours worked to the proper cost center that flows to the general ledger and accounting systems (see Chapter 8 for more detail on the general ledger). Timecards are tightly integrated with accruals and attendance. Basic timecard functionality usually includes simple timekeeping inputs. If the organization wants more capability than their basic WFM system provides, separate modules for additional features such as attestation, advanced accruals, optimized scheduling, analytics, and leave management may be added. These capabilities are discussed in other sections of the Workforce Asset Management Book of Knowledge (WAMBOK).

Timecards represent the basis of the timekeeping system. Their basic functionality is a necessary part of the timekeeping system and a helpful organizational management tool for managers and supervisors. Their design dictates much of what the organization can harvest from WAM systems in terms of detailed, credible, and timely information. From the basic timecard, organizations have the potential to grow in a variety of directions—it all depends on what their requirements and objectives are.

5.2 ACCRUAL RULES8

Workforce management systems have long played the role of reporting and managing paid time off, or benefit time, such as vacation, sick, personal, and leave. These benefit hours are dictated by human resource policy, which defines the eligibility, method of earning, and proper use of benefit time. Benefit policies come to life inside timekeeping and scheduling applications where the rules must be configured to appropriately capture and report paid time off. These rules are commonly called accrual rules.

Each type of benefit is assigned an accrual code. These codes are designed to hold the available balance of hours the employee has earned. An employee may be eligible for more than one type of accrual code or benefit type. Each type may have different rules and hours. The timekeeping system is used to report the date these benefits are used, enforce the use of the benefit, and track how many hours were used by event and who entered the data and when.

Accrual code setup often includes an anchor date—the assigned date for defining the rule. The WFM system is configured to establish an accrual policy for eligible workers and the anchor date tells the system when this policy starts. This may be January 1 for a system-wide policy or hire date for an employee-specific requirement. The WAM-Pro must understand how dates impact the accrual program.

Date patterns may be a design component of certain rules. Date patterns are cycles of time for when something should happen within an accrual rule. For example, monthly grant of hours, annual grant of hours, 90-day probation, quarterly earning maximums, or even rules to limit hours taken with a period.

It is not uncommon for employers to establish rules around a probationary period or a waiting period before an employee becomes eligible to participate in a benefit program. Probationary periods are periods of time when an employee cannot use benefit time—such as the first 90 days. The WAM-Pro can set up rules that establish the hire date, define the rules during probation, and the trigger for turning on the standard rules once the probationary period has been met. There may even be levels of eligibility such as within the first year but after the 90-day probationary period. These nested rules can also be configured but become much more complex. The benefit of WFM system is that enforcing nested rules is much easier in an automated system than a manual one.

Events may also be an accrual driver. Some employers award time-off hours based on working time. One example might be additional benefit time earned upon working a set number of consecutive days in a row. Or anniversary dates commonly play a part in determining when an employee is eligible for more time off.

Accrual rule setup will require defining limits for the accrual usage. There are several types of accrual limits that should be defined in the benefit policy.

- Taking limits are the number of hours that can be taken in a day, week, month, or year. For example, exempt employees may be required to take time off in full eight-hour day increments. Hourly employee policy may require that time off be taken in at least 15- or 60-minute increments.

- Earning limits are the number of hours that can be earned in a week, month, or year.

- Carryover limits are the number of hours that can be carried over from one period to the next. A common carryover limit is that a set number of hours can be carried over into the next calendar year. This helps an organization manage its benefit liability (cost). Some organizations have a use or lose policy that prohibits employees from carrying over any unused accrual balance. WFM systems can be set up to enforce these limiting rules to maintain fair and consistent application of benefit policy.

The number of hours in the employee's accrual bucket can be imported into the WFM system from another database, or the hours can be system-generated inside the WFM system. Imported balances generally come from the human resource information system (HRIS) where complex human resource (HR) policies are administered. Even if balances are not computed inside the WFM system, the WFM application may still be responsible for considerable management of the limits and reporting. Calculated accruals designed inside WFM systems work well when the policy requires the system to handle complex accrual-earning rules based on time worked, shift length, average hours, and other reported time and activity inside timekeeping systems. Set up can include grant rules, which establish how hours are distributed, or granted. These may be fixed—such as eight hours per month, or earned—such as number of hours times a factor of time worked.

These rules—limits, grants, and taking—can vary by employee group and many employers have more than one set of rules. The WFM systems are set up to put these rules together in any combination under the accrual policy. The accrual policy combines the particular set of rules into a set of hours rules to apply by accrual code. These policies can also be tiered where, based on tenure, the employee's accrual policy will change over time. In years one to five the employee's accrual policy may be designed around Combination A, in years five to eight around Combination B, and after eight years around Combination C. The goal is to make policy administration automatic and consistent with as little manual intervention as possible.

Finally, depending on the system, an employee who is eligible for multiple accrual types may have a profile that combines all available accrual benefits into a single profile. This way employees' jobs or departments can flag the system to assign the proper profile and automatically apply and enforce all of the applicable accrual policies to their bank of hours.

WFM systems can handle a multitude of complex accrual programs. The WAM-Pro needs to understand each of these discreet system features and company policies so that accrual costs are managed appropriately. Accruals are engaged within WFM systems via timekeeping, collection devices, scheduling, leave management, and analytics systems.

5.3 AUTOMATED WORKFLOW AND EMPLOYEE SELF-SERVICE9

The term automated workflow is often misunderstood. Some organizations fear that automated workflows in WFM systems will take away control. However, once the term is clearly understood the fear of automated workflows is alleviated and organizations begin to promote them as labor-saving processes. A description of an automated workflow in a WFM system follows.

Automated workflows in WFM systems are configured programs in the software that will automatically perform activities based on the user requirements. For example, someone fills out a timesheet that needs approval. The timesheet is filled out and submitted electronically. It is automatically and immediately forwarded to the person who has the authority to sign it. If that person indicates that he or she will not be able to sign it at that time it will then automatically go to the next person with authority for signature. Another example is automated time off requests. The employee submits the electronic request online. The system routes it to the appropriate approver who is promptly notified of the request. Once electronically approved, the system not only notifies employees of their accepted request, the system also updates both the timecard and schedule records so that proper staffing changes and payments are made. There is no paper, and minimal effort is exerted to deliver these messages to the right person for prompt approval. In addition, there are no overlooked steps and the systems are simultaneously changed with up-to-date information. There are a variety of workflows that can be configured in a WFM. These are described in the next paragraphs.

(a) Benefits of Workforce Management Automated Workflows and Employee Self-Service Tools

The following are a variety of benefits of an automated workflows and self-service tool. Not every organization will realize all of the benefits or use all the types of available workflows.

- Efficiencies for manager, employees and system functions. Workflow automation improves labor efficiency by having some work performed automatically by the computer. This increases productivity by allowing managers and workers to focus on other needed work.

- Timeliness (real time). Automated workflows allow immediate monitoring of work so modifications can be made as needed without the time loss and expense of delay.

- Ease of access and use. Workflow software is simple to use so the nontechnical employee can learn it quickly to view vital information such as scheduling coverage, work hours, paid time off (PTO) requests, and personnel information.

- Accuracy of data and schedules. Data entered into the system is real time, so the accuracy of the entered data is current at that point in time. This is particularly important for identifying and reacting to absences and schedule changes.

- Cost savings. There are a variety of cost savings from reduced staff hours and nonproductive worked time. This helps the organization to develop a more accurate, long-term budget plan and enact stricter policy enforcement.

- Flexible scheduling increases employee autonomy. Workflows aid in the implementation and management of flexible scheduling programs that increase employee autonomy, enabling employers to attract and retain the most highly recruited human-capital assets and be responsive to employee needs and circumstances outside of work.

- Green initiatives. Many companies have implemented a go green initiative to reduce paper. Employee self-service provides reports that are viewed and approved on screen rather than printed.

(b) Functionality of Automated Workflow System

Automated workflows provide impactful solutions to some of the common problems experienced by organizations. Again, workflows are optional and dictated by the business needs.

- Report, approve, and update time off requests. Employee-generated leave requests appear in a manager's e-mail inbox or software dashboard for review and include details such as the type of request, days and/or hours requested, and the employee's accrued PTO, sick- and/or vacation-accrued balances allowing a manager to view each employee's schedule for the amount of PTO requested to facilitate proper coverage, and a reply is then sent to the employee notifying him or her if the request was approved or denied.

- Generate and distribute reports. The system calculates, approves, and distributes data on employee activity and hours automatically and may include printed reports, e-mail, or software dashboard.

- Approve and escalate timecards. Often employees submit timecards for supervisor approval after their own approval. The next step is for the timecard to be sent to payroll for processing. With automated workflows, each of these steps is automatic with an audit trail to show if changes were made and who made the changes.

- Alert managers to exceptions. An exception report can be set in the workforce management software to alert a manager when data is not within expected parameters. Examples are tardiness, excessive lunch breaks, or early completion of work. Exception alerts can be e-mailed or posted to managers as they occur.

- Track absences, generate a report, and send the report for attendance tracking. Similar to exceptions, any variance to an employee schedule can be generated and sent to the appropriate parties. These reports can be auto-generated or polled from the database at any time. Some systems offer advanced attendance policy workflows that enforce point systems for absences, execute disciplinary instructions, and document the corrective action activities automatically.

- Sign up for a schedule. Workflows allow employees to select available schedules provided they meet the other requirements for those scheduled shifts and can be governed by employee seniority or by job classification title.

- Swap shifts. Employees can exchange shifts and provide a management audit trail to facilitate proper coverage.

- Review available balance of time off. Workflows can be set up to have multiple time-off policies with different configurations and rules assigned and reviewed by each individual employee.

(c) Considerations When Planning an Automated Workflow Process

When implementing an automated workflow in a WFM system there are several steps to take and parameters and processes to consider.

- Document the automated workflow process. Once requirements and rules for an automated workflow process are determined a schematic diagram should be created to provide a visual picture of what will occur. It shows the user how the solution will function and how employees and management will interact with the application.

- Time calculations. The workflow should take into account the total time it takes for a task to be completed and be broken down into the actual series of work tasks and nonwork time during the effort.

- Distribution options and backup. A workflow process should have redundancy at many levels, including management. To prepare for absences by people in the workflow, cross-training of peers is recommended for the instances they may need to assume the role of the absent manager. If there is not an acceptable peer replacement, a higher level manager can assume the duties temporarily. Automated workflow applications should have a place to assign a substitute or proxy in the event a position on the escalation tree is vacant.

- Inherited security. It is important that employee data is managed properly and securely within a workflow. Proper filtering of data by location, department, division, and manager is crucial to make certain critical and often confidential employee information is not viewed by unauthorized persons.

- Access. Some automated workflow processes allow activities beyond the normal working hours and while employees are not at work. Self-scheduling and the reporting of unplanned time off are two examples. Remote system access may become an essential part of the overall design and processes. Personnel may require special devices or networking not otherwise needed. Expectations around the timing of such interplay should also be determined. Should employees expect a response within a certain amount of time during off hours? Is activity performed during nonworked, off-site time compensable? Complex issues such as these may require involving areas such as the legal department (participants not normally included in routine WFM system design).

- Errors and lost data. Automated workflows may require contingency plans for reestablishing the process in the proper sequence, recovering data, and meeting operational timing requirements in the event of a system error or failure. These plans should include both technology recovery strategies as well as manual processes and personnel escalation plans to make certain operations and personnel are not negatively impacted. Mission-critical processes may require extra redundancies.

Automated workflows in a WFM system are beneficial to the business and employee by providing significant time-saving processes that are done without human intervention. If set up and controlled properly it allows managers and employees to perform other tasks so productivity is increased. And, the risk of using automated workflows is minimal because management designs and controls the automatic work being performed. Automated workflows also enforce policy and procedure guidelines and provide a useful audit trail of user requests and inputs instituting greater consistency and equity across the organization. The timing, business needs and benefits, and the participants involved in automated workflows should be carefully considered when implementing a WFM system.

5.4 DATA COLLECTION: WHO, WHERE, AND WHEN

A WFM system depends on two features: rich data and a platform on which to synthesize it. At its most basic, a data collection system should be able to capture information on who, where, and when. Put simply, the technology must be able to collect the right information at the right time, in the right location and in the right manner to meet the needs of the organization.

If well executed, a WFM system will reduce recording errors, enforce pay and attendance policies, minimize opportunities for fraud, assist in compliance with labor and leave regulations, and enable the organization to aggregate data for further analysis. When used to its full potential, it will enable improved efficiency and better decision making.

This does not imply that the most powerful systems will be right for every company. The decision of which system to purchase must incorporate the size, budget, technical requirements, and organizational structure of the company.

(a) After Hours: Moving beyond Timekeeping

In the past four decades the technology to collect data has evolved significantly, moving from simple wall-mounted time clocks to interactive touch screens and new mobile, handheld devices. At many companies, systems are linked to physical or cloud-based networks that support not only the payroll function but also a wealth of integrated workforce management decision support tools, including analytics and reporting.

Today, the devices used to document time and attendance may also be used by employees or employers to manage scheduling, monitor benefits accruals, enforce compliance (e.g., consistent application of work and pay rules, enforcement of complex Fair Labor Standards Act [FLSA] or union rules, monitoring of overtime pay or comp time), communicate messages, or control workplace access. They may be linked to GPS to enable employers of a mobile workforce to track and route employees as they move from one location to another and to affirm worker identity.

Systems can be configured to associate data with specific employees, tasks, or shifts for cost accounting and workforce optimization, and can link employee IDs with data such as rates of pay or work assignments. Importantly, they can also accept and track inputs as an employee moves from one task to another, from one project to another or from one location to another, making it possible for companies to obtain a more systematic understanding of project or product labor requirements.

Once collected, this data can be used to track business segment productivity, measure unit costs, and better understand the actual time required to perform certain operations.

(b) Data Collection Technologies

This section explains the primary types of data collection technologies. The easiest way to think about data collection technologies is to divide them into two categories: fixed location and mobile location.

For both, however, there are also software platforms that can be used to aggregate data for future analysis. With the continued evolution of scalable Web and cloud-based technologies and handheld computing devices such as tablets and smart phones, we can expect the lines between fixed and mobile technologies to continue to blur.

Where the data is collected—particularly its proximity to where the work is actually being performed—is a critical component of a successful WFM system. To minimize gaps between the time an employee clocks in and the actual start of work (time inflation), data collection should, ideally, occur as close as possible to the moment that work begins. Whether unintentional or purposeful and fraudulent, such time inflation can be costly. The ability to track it and minimize it becomes especially important when the role of the WFM system includes not only payroll but also other strategic and operational considerations. Enabling workers to report their activity as it occurs also reduces errors and omissions.

(c) Fixed-Location Data Collection

Fixed-location devices are used by employees of companies who report to work at the same site each day (as opposed to working on the road or in multiple worksites throughout a day). As the name implies, they are mounted in place, typically near entrances, work stations, or break areas. They might be found in factories, schools, offices, stores, hospitals, and so on.

i. Electronic Time Clocks

Historically, the most common fixed-location devices for the collection of time and attendance data has been electronic time clocks that feed information directly into a network and/or a database. Data from electronic time clocks is aggregated automatically via push or poll technology, described later. Depending on the system configuration, data can also be fed into payroll, HR, benefits, or even billing applications and vice versa. Data from these other systems can be fed back to the time clock device for rule enforcement and data retrieval by employees.

In most cases, vendors of time management technologies can furnish either software, hardware, or both.

Common features of fixed-location electronic time clocks include:

- Magnetic stripe badge scanners. Badge scanners read a magnetic stripe, typically located on an employee's ID card that communicates data to the time and attendance system via a network connection when the card is swiped. The stripe contains preprogrammed identifying data about the employee that can include not only employee ID, but also access control instructions, payroll records, labor management data, and other information.

Although these badges are among the most commonly used devices for corporations of various sizes today, this technology is now being replaced by radio frequency identification (RFID), key fob, and similar near-field technologies (described later) that do not require physical contact during the swipe and that are, hence, less vulnerable to use-related wear and tear.

When considering magnetic stripe badge scanners, it is useful to understand that the scanner component is most likely to be affected by friction in the read head, which reads the magnetic data into the system when a card is swiped. Magnetic stripe scanners are also susceptible to damage from dust, dirt, and small particles, which can reduce their effectiveness in manufacturing plants or in environments with high levels of particulate matter or grime. Magnetic stripe readers are available in vertical and horizontal configurations. If particulates are a consideration, the vertical mount reader is preferred to minimize accumulation. Regardless of the mounting configuration, the readers should have periodic cleaning with special cards to improve performance. - Bar code scanners. Employees use bar code scanners in a similar manner to magnetic stripe scanners in that they swipe a card across a reader. However, bar code readers use light (either direct or infrared) to read data rather than requiring physical contact with read heads. This makes them less vulnerable to friction-related wear and tear as well as to the effects of dirt or particulate matter. In general, bar code scanners are slightly more expensive than magnetic stripe badge scanners, although the reduced maintenance on these devices can offset some of the added cost.

Among the disadvantages associated with bar code technologies is the relative ease with which the bar codes themselves can be copied and reproduced. This replicability, which makes bar code scanners less effective at preventing buddy punches and less reliable for use in access control, is a primary reason that bar codes are not popular for tracking time, attendance, or security.

Scannable bar codes are, however, particularly effective for use in job costing and production management, and are used in many industries as a supplement to other time and attendance tracking devices. Department names, work orders, and actual numerical values themselves are representable by bar codes. By creating a job sheet that associates specific scannable bar codes with a project, product, or work phase and asking employees to scan these codes at the start or cessation of a task, employers can track and analyze time spent on particular tasks, restrict employees from punching into a job if not authorized to do so, monitor processes that are requiring excessive overtime, and so on. Significantly, bar code representation allows for greater data accuracy, because the information is captured mechanically and is not prone to transposition as a result of human data entry.

To better leverage the job-costing benefits of bar code technology, bar code scanners are sometimes used in tandem with other, more secure technologies. As a tool for overall time and attendance management, however, bar code scanners are waning in popularity.

ii. RFID Tags and Near Field Communications Device

RFID (radio frequency identification) tag and near field communication (NFC) device (which is like RFID but works in much closer range) are wireless, noncontact devices that workers can swipe to clock in or out or to track the beginning or end of a task. They can be inserted into a variety of formats such as a key fob, card, wrist band, and so forth.

Most companies that choose the proximity option do so to reduce transaction time. Because the read range is usually 4 inches to 7 inches from the electronic time clock, throughput is faster than a swipe clock.

Once considered too expensive for small- to mid-size businesses, the price of RFID and near field technology has dropped significantly and is now beginning to overtake magnetic stripe and bar code options for businesses of varying sizes.

Among their advantages, RFID tags have no moving parts and are less vulnerable to friction-related wear and tear or to dirt. This makes them well suited to office as well as manufacturing or lab-based settings.

However, RFID is still prone to buddy punching as someone could have their buddy take their card and punch them in or out. Using this technology also requires that employees always have their card on them. For those who perform the administrative duties necessary for RFID cards, there can be considerable inconvenience around losing and replacing employee cards.

As noted, there are several RFID applications:

- Proximity technology. An electronic key (magnetic stripe, bar code, and Weigand are examples of other electronic keys). The proximity electronic key is simply a medium through which to transmit information between two points. The proximity card (or key fob, wrist band, etc.) does not store any sensitive information within the credential. An example would be the validation transaction at the electronic time clock to the confirming WFM software. Notably, proximity technologies do not typically utilize passwords, which make them less secure if downloaded or stolen. WAM-Pros must weigh the need to maximize efficiency against the need for validation.

- Smart card. Another form of RFID credential is a smart card. Capable of holding large quantities of data, they can be used for time and attendance tracking as well as for access control, job tracking, and other purposes. Smart cards would be more applicable for larger settings such as university campuses, hospitals, or large institutions, where they can be used by employees who may use one card to access not only the WFM system, but also for cafeteria purchases, gift shop purchases, parking privileges, and so on.

- Biometric inputs. Identify employees by a specific biological identifier such a finger scan (slightly different from a fingerprint, this technology scans the topography of the finger or veins within the finger), hand geometry (which tracks the full size and shape of the hand), or face. Along with RFID technologies, biometric solutions are now a growing trend in the industry.

Biometric identifiers work by converting an image of the employee's feature into an algorithm, which becomes the baseline for future comparisons. Baseline images for hand and face recognition are usually recorded with two cameras to create a three-dimensional image. As technology improves and costs decline, many more biometric devices are being adopted in the workplace. The rising popularity of cameras embedded in cell phones make the use of facial recognition technologies particularly attractive for mobile workers as well.

Biometric readers for time and attendance are often used in conjunction with security and access control systems and to reduce opportunities for buddy punching or ghosting (any of a number of fraudulent arrangements that may entail nonexistent workers or workers who sneak away from the premises after clocking in). Biometric readers are especially useful in high-security or restricted access facilities such as hospitals, government sites, and schools.

As with magnetic stripe devices, it is important to consider the physical environment in which a scanner is to be used. This includes temperature, particulate matter, and surface grime (on the device or the employee's hand) as these may interfere with the device's ability to read an image fully.

Companies wishing to add biometric identifiers to existing hardware or software infrastructures can often do so, provided that the new software and existing hardware are compatible. (For more details on biometric devices, see the “Biometrics: Features and Functionality” section later in this chapter.)

iii. Computer (Desktop)

These applications enable employees to input hours worked and manage scheduling or attendance by logging in from their computers. This makes them popular for administrative workers as well as personnel in law, accounting, consulting, or architecture firms who must track billable hours by attributing work to clients or projects.

Logging in as opposed to clocking in makes desktop transacting more palatable for white collar workers. Desktop systems can be set up to allow employees to log in and out or log in only, using the time programmed into the company's server (which means that each individual employee cannot alter the time), or the employee can be given the freedom to enter lump sum hours, project hours, individual shifts, and so on (e.g., a lawyer might enter daily hours in terms of time billable to each client).

Companies with a mix of exempt and nonexempt employees will often use desktop systems in combination with more traditional time clock technologies to manage attendance or benefits for exempt staff. In these cases, the software system may be configured as a bolt on component to the primary timekeeping infrastructure. Computers can also incorporate biometrics and other forms of security to validate user identity.

iv. Devices for the Visually Impaired

Several options exist to accommodate the needs of visually impaired employees. Among these are interactive voice response (IVR) solutions, available through the telephone, which can link to various workforce management systems that can utilize voice recognition biometrics. Other options include terminals with larger screens, sound feedback for various functions, microphones and cameras for employee voice recognition interaction as well as Braille key indicators on the key-pad overlay.

v. Devices for the Hearing Impaired

Telecommunication services and devices for the hearing impaired can be used in combination with WFM telephony systems making them accessible to hearing impaired workers. In this way the worker can key in responses that are relayed to the employer WFM system. The voice activated system responses are fed back by an operator over a special machine that the worker can view to read the messages and respond. TTY and TDD services are discussed further in a later section.

(d) Mobile Data Collection

Mobile collection devices are used to aggregate information from workers who operate in the field, either in a single remote location during the day or in multiple locations throughout the day. This includes among others, telecommuters—home-based workers, who clock in not only to verify payment but to verify work completed or to establish other data, such as project attribution—and remote field workers who clock in and out of multiple job sites throughout the day or throughout the week. Remote field workers span a wide array of job categories such as construction workers, carpet cleaners, support technicians on multiple job sites, home health workers, couriers, and a host of others. Mobile devices, because of their ubiquitous presence in the market as well as their low cost and improving functionality, are sometimes replacing traditional time clocks even for workers who do not require mobility based on their location.

Mobile data location collection devices include:

- Telephony (via traditional landline). Phone-based technologies enable mobile workers to dial into a toll-free telephone number, and clock in or out by entering a PIN and/or a pay code. As needed, these systems can also validate the location of a landline via caller ID (telephones are preregistered with the employer for this purpose) or by geo-tagging to ascertain the location from which a call is made. If the number of preregistered phone numbers is not high or not subject to change frequently, this is a viable option. For certain industries, (e.g., home health workers who work with new clients every day) maintenance of the preregistered numbers can become a challenge. There are ways to automate this system. The first way uses IVR (interactive voice recognition) where anyone can use any phone to call into a central call database, which the vendor hosts. The worker can punch on arrival or departure to the office, to lunch, and so on. However, if caller ID is desired, it might be nearly impossible to keep up to date with a new work site/client locations. The other way for automating uses a smart phone with a GPS component. So if a mobile worker uses a smart phone to log in to the system, the employer will have the GPS coordinates for documentation and authentication purposes. Land-line telephone-based systems are useful for an employee base that may not have access to computers or cell phones. Technology add-ons can include:

- IVR (interactive voice recognition). Enables employers to verify employee identity through voice recognition. This technology is particularly popular in the home care industry, in building services, and similar industries.

- ANI (automated number identification). Recognizes the incoming phone number and determines whether it is on the system's list of valid phone locations. This technology prevents employees from calling in from a nonwork phone and can be used in conjunction with any phone line data entry (landlines, cell phones, etc.). ANI can be used to simply report or fully restrict incoming calls based on the incoming phone number.

- Text/SMS messaging. An option for cell phone users, text and SMS messaging enables employees to clock in and out by texting a message to a specified phone number. This option alone, however, cannot be used to verify location and employee identity.

- MMS (multimedia messaging service). Enables employees with mobile phones to take a photo and send it into a system with accompanying text. The MMS option can also include geo-location. Background images can be used to verify location and dress code can be verified.

- TTY/TDD (telephone-to-telephone typewriter. Also called a textphone in Europe or a Minicom in the United Kingdom). A telecommunications device that enables hearing impaired employees to report their work activity through telecommunications relay services that connect TDDs to the telephone system. Newer variations that leverage the Web can reduce the need for TDD. These can also include an Internet Protocol (IP) relay, video relay, and IP-captioned telephone service.

- Smart phone technologies. Smart phone applications can be configured to do nearly anything that a PC can do from basic clocking in and out to payroll and benefits-related reporting, schedule/shift management and verification, messaging, and even billing, among others, while accommodating the needs of a mobile workforce. Most companies use off-the-shelf WFM technology applications, although some larger companies will develop applications in house. Add-ons can include:

- Biometric capabilities. Smart phones can be equipped with some of the same biometric identifiers (finger scan, facial recognition) that are used in fixed data collection systems. Transmission of this data via wireless networks can present a challenge where connectivity is erratic. Availability of mobile phone biometrics using facial recognition is limited, as few vendors offer this feature at this time.

- RFID and near field capabilities. Smart phones can be configured to accept RFID and near field inputs.

- GPS. GPS overlays to cell phones—particularly when combined with biometric inputs—provide additional ability not only to affirm each employee's actual whereabouts as the worker clocks in, but also to improve the routing, scheduling, and dispatching functions by enabling real-time assessment of schedules and locations.

- Tablet computers. Whether wall mounted or mobile, tablet computers have begun to find their way into the industry. These devices are able to accommodate time clock functions, identifying employees using PIN entry, barcodes, touchpad entry, RFID badges, or biometric inputs while also collecting time and labor data. They are able to push information to relational databases established by the company as needed. Current technologies can monitor and alert employees to likely punch errors, communicate in multiple languages, enforce scheduling rules, and store data, among other features. One of the greater benefits to using a tablet computer is the possibility of either Wi-Fi or a data plan through a cellular network carrier, which can allow for remote or wireless connectivity in more locations.

- Mobile specialty hardware/personal digital assistants (PDAs). These portable devices include scheduling and time-management technologies that are often tied either to the Internet or to a centralized dispatch unit. They can be handheld, mounted in a vehicle, or located at a fixed, semipermanent job site (such as a construction site), and can have biometric identifiers as well as bar code scanners. They are common in the package delivery industry. Common challenges with these devices are upfront costs associated with purchasing and updating a specific hardware device.

- Data collection field terminals. These devices are most often battery-powered, and can communicate back to the host via cell modem and/or postworkday through a charging/communications cradle that sends data to the host software or by downloading transactions to a thumb drive to be uploaded then at the host computer.

(e) Push and Poll: Integrating Data into Time Management Systems

Data collected by a WFM technology system can be aggregated in two ways:

(f) The Future

The industry is moving increasingly toward Web-driven solutions with companies opting to host and aggregate data on open platforms integrated with HR and payroll. This trend will support applications that are more strategic and less transactional in their focus, enhancing companies' ability to track and meet key performance indicators and other productivity drivers.

Devices for the collection of data for time and labor management will focus increasingly on creating one avenue of input to feed multiple back-end uses, with increasing amounts of user-specific data (such as language, task, and employment data) linked to each employee's timekeeping device. Expect to see increasing use of touchless cards (Mifare) that can hold sizable quantities of data, streamlining the process of managing time, security, and so on, as well as the use of more real-time data. In the farther future, employee-centric systems may be available that will enable staff to link their payroll information directly to bill paying systems or similar. Some industry pioneers are even looking at devices to project software applications directly on users' own bodies, turning users themselves into input surfaces.

Nearer term, GPS tracking will continue to play an increasingly large role, particularly for tracking mobile employees. Technologies are already in place to provide breadcrumb trails to record employee whereabouts, vehicle speed tracking, tracking of vehicle idle time, mileage tracking, and smart fence technologies that notify employers when an employee crosses a specified geographic boundary (as small as a building or as large as a state). In the coming decades, it is possible that interior GPS and clip-on devices such as intelligent wrist bands may replace swipe technologies.

5.5 BIOMETRICS: FEATURES AND FUNCTIONALITY

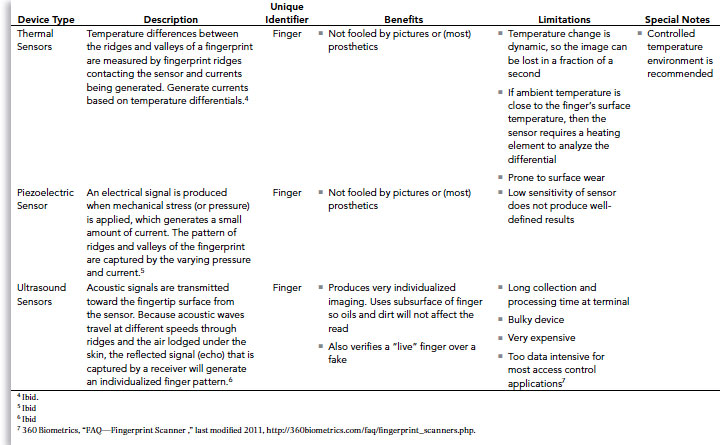

Biometric devices are one of the more controversial issues in the workplace today. Recently, biometric technology has become more available and affordable, and as a result has also become a more predominant feature in the workplace. Understanding the basic features and functionality can be mutually beneficial for both employer and employee. Table 5.1 provides further details on many of the biometric devices in use today. But before going into the specifics, it is important to look at the common challenges, benefits, and pitfalls of biometric devices and systems.

Table 5.1 Biometric Devices: Features and Functionality

http://www.wiley.com/WileyCDA/Section/id-816176.html

(a) Common Challenges of Biometric Systems

The following is a sampling of the common challenges faced by organizations when working with biometrics systems.

- Match threshold levels. Because verification is so integral to the biometric collection process, there must be a method to assess whether users are who they claim to be. The match threshold levels establish balance between false acceptance rate (FAR) and false rejection rate (FRR). FAR measures how often a nonauthorized user is falsely recognized and granted access to the system. FRR measures how often an enrolled and authorized user is denied access to the system. If the threshold is too strict or high, then security will increase. However, very few users will be able to access the system because they will not be able to pass the threshold. The opposite is true for a low threshold. In the case of FRR, if too many users are experiencing difficulty accessing their individual biometric identifier, it is recommended that the organization configure a 1:1 matching (i.e., users first enter their user ID, and then use their biometric feature for verification).1 When purchasing a biometric device, ask the vendor whether the technology can establish thresholds at the employee level for increased security, or if it will need to be more uniformly programmed.

- Sanitation and cleaning. Sanitation has consistently been a part of the conversation when it comes to biometrics. Many users are concerned about germs and cross-contamination when coming into contact with a device that other employees have touched. Although proper safeguarding procedures should be considered, contact with a biometric device transmits as many germs as touching a doorknob.2 However, proper cleaning methods should be followed with biometric devices in order to properly capture biometric data and decrease FARs and FRRs. Because touch screens and sensors are becoming commonplace in the workplace, understanding how to care and maintain these machines is critical. When cleaning a device, make sure to know and understand the following:

- Cleaning frequency

- Cleaning method (wet versus dry)

- Avoid magnetic objects

- Avoid static electricity

- Maintain clean hands/fingers

- Maintain stable power (voltage)

- Specified temperature range

- Handling (be gentle)3

To help mitigate concerns over the transmission of germs, it is often recommended to provide hand sanitizer next to the machine or locate the machine near a washing station.

- Space and placement. Before being swept away or sold on any special feature or function, an organization should consider the size of the device and if its placement would be feasible in the space they operate. A bulky device located in a main entrance or a small corridor that would create unnecessary congestion is not appropriate. The inconvenience that it will create may have the employees resenting it before they even learn how to use it, which hurts the overall functionality of the product. As a part of requirements gathering, the WAM-Pro should do walk-throughs throughout the building(s) to assess how much space is available and determine the preferred placement for the device(s). Considerations should include items such as user accessibility, security, proximity to a power source, and installation costs (e.g., distance from PC or networking equipment). Sounds (e.g., beeping) should also be considered to avoid disturbing employees who work nearby. They can also talk to employees to understand where the convenient and accessible spots are. Sensitivity to space and placement will increase the device's ability to perform and deliver expected results.

- Security and privacy. The term fingerprinting carries a negative connotation, as people assume that it is correlated to monitoring or investigating criminals. However, biometric devices used in the workplace are neither storing highly sensitive data, nor sending information to authorities. The scans and/or measurements are converted and stored in a template made up of data points (1s and 0s) directly on the machine or the software/service database. This biometric template is then read by the system to confirm that user. The mathematical representation (binary code) of the individual's biometric reading is not compatible with law enforcement systems.4

(b) Common Benefits of Biometric Systems

Biometric devices clearly have advantages in the workplace and help employers and employees accurately report their work activity. Below are some of the potential benefits:

- Significantly reduce payroll inflation (i.e., fraud, gaming, human error, buddy-punching, extra sick/leave days, reducing avoidable overtime).

- Increase the enforcement of correct and impartial pay rules.

- Increase the consistency and fairness of absence management tracking.

- Reduce payroll processing time because manual entry and verification are not necessary.

- Increase personal security (i.e., restricted entry for workplace on premises).

- Increase protection of employer during audits and against litigation and claims.

- Better management and authentication of mobile workforce.5

- Integration of payroll with other secure-access functions (e.g., gate/door access, PC access).

(c) Common Pitfalls of Biometric Systems

The following are some of the common pitfalls experienced by organizations when using biometric systems.

- Setup costs, including purchase/lease and installation.

- Maintenance costs.

- Time to train both users and payroll personnel.

- Labor union and religious objections.

- Technology glitches (reliability, power outage, etc.).

- Setting appropriate thresholds to capture biometric data (what passes and what does not).

- Staying ahead of the technology curve.

To make better decisions about selecting and using biometric devices or systems, it is important to know their specific features and functionality. Table 5.1 provides a basic overview of how the device operates and some details of what to expect.

5.6 MOBILE RESOURCE MANAGEMENT: FEATURES AND FUNCTIONALITY

Mobile resource management (MRM) has answered the call to provide real-time data for real-time organizations. The mobile workforce is a growing entity across many industries. No longer are all employees housed under one roof—they may not even be within the same country. Managing this new workforce is challenging, but MRM technologies provide transparency and may even be able to mitigate problems like: low productivity, inflated payrolls, on-premises staffing, or overbudget costs. It is an efficiency and visibility solution for organizations looking to mature.

Some MRM technologies in use today are:

- Bread crumb tracking. Using latitudinal and longitudinal data points, employers can have precise, real-time GPS maps of employee or product movement in a geographical area. This can include actionable data like clock in/out, meals, breaks, or different activities during the job. The GPS mapping can be set to the company's preference (i.e., update every 30 seconds, every 300 feet). Each time a GPS coordinate is captured, the mobile device will transmit latitudinal and longitudinal data points back to the server. The server can generate a physical address and create a trail. This real-time report can even monitor speeds at which vehicles are traveling across these points.

- Smart fence (geo-fence) technology. A boundary or parameter is set up around any location (i.e., construction site, neighborhood, building, geographical borough). Any time an employee enters or leaves this boundary or parameter, it would clock the employee in or out. When an employee clocks in/out, a notification can be sent to an office administrator or field manager (via text or e-mail), so that employers do not have to watch the fence, but are simply triggered when something happens. This technology can auto-populate a timesheet with exact times (i.e., clocked in at: 7:57 a.m.; clocked out at 4:59 p.m.).

- Speed and idle time triggers. A form of tracking service that can be set so that when a speed or time limit is violated, an alarm or notification is sent out to both the employee and the employer. It is often used for vehicles and transmits data wirelessly either through a cellular or satellite communication. Both speed and idle time triggers can have responsive actions associated with them (text message or e-mail letting employee and employer know that a trigger has been broken). Smaller businesses therefore do not need to invest their time watching the screen constantly, but rather just receiving notification when needed. The specific definitions of speed and idle time triggers follow.

- Speed triggers. For transportation and delivery industries, this can track how fast the vehicle was going and will notify when speed limit is broken (doing 45 mph in a 25 mph school zone).

- Idle time trigger. GPS monitoring that shows where the employee is at a specific time. This trigger would show if the vehicle/employee had been idle for 15 minutes, 1 hour, and so on, and at what location.

- Near field technology (NFT). Allows devices to communicate with one another when coming within physical contact of one another (i.e., cell phones with time clocks—two devices touch and transmit information; also contactless smartcards and RFID—radio frequency identification tags). Facilitates simple set up of wireless capabilities (Bluetooth, Wi-Fi, etc.), works with existing contactless cards, and has a short range (must touch or be within centimeters). This technology interacts with the N-Mark, an identifying tool for the NFT device.

(a) Benefits of Using Mobile Resource Management

Cost effectiveness is normally a primary concern for the buyers. But MRM devices and technologies could yield more than simply cost reduction or ROI. For WAM, it could be a step that pushes an organization toward maturity.

Because many of these devices interact with, or can be implemented on, already existing technologies (i.e., cell phones, mobile devices) MRM solutions can be very cost effective. Employees will not even be required to have advanced technology (smart) devices. Standard cellular and mobile devices can easily administer these technologies. The actual systems might only be a few dollars per month per employee, but the savings from increased employee productivity and accountability can make up for this. Real-time access to location and movement of resources can not only assist with productivity, but also lead to better efficiencies in travel time, map routes, and fuel usage. A WAM-Pro uses MRM tools to help the organization act more resourcefully and utilize assets to their full potential.

Moving an organization forward and going paperless can save money in supplies, but more importantly, it can help to avoid duplicate entries. Savings from this may even cover the cost of the service—it is a considerable benefit to ROI. Paperless systems, like MRM technologies, also reduce the potential for human error. Employees cannot forget to clock in or submit their timesheet. Managers and employers may be less likely to incur litigation or grievances because the automatic system tracks and analyzes time and attendance data, so there will be fewer possibilities for pay inaccuracies. The systems that can fully integrate with payroll systems will alleviate payroll from this tedious process and will create enhanced reports with more actionable data. This form of systematic documentation and automation reduces administrative costs, while continuing to maintain compliance with state and federal wage and hour laws.

(b) Challenges and Issues When Using Mobile Resource Management

One of the greater challenges for MRM today is coverage.6 If an employee is in a remote area (whether that be a mine in West Virginia, or the basement of a hospital in Washington, DC), it is difficult—if not impossible—to transmit or view data. Without a connection or with heavy interference, there can be no real-time value, which is a marked feature of MRM. To overcome this challenge, some vendors have created systems where the MRM device is mounted locally, such as in a car or on the actual mobile cellular device itself. In this case, timekeeping data could be stored and sent over the network later when the connection is restored. The data is still usable, just delayed.

This issue is related to another concern over coverage. When implementing an MRM system, it is important for employers to check connectivity and determine whether service providers can adequately cover the geographic territories that the employer operates in. For example, if a smart fence is set up in a construction zone on a major interstate, then not only will employees clock in and out when they come and go to work, but also whenever they use that road. Handling such exceptions could be troublesome.