CHAPTER SEVEN

State Regulation1

IN THIS CHAPTER, STATE WAGE and hour guidelines are defined and explained. Unlike federal regulation, state regulations vary greatly among the states. It is critical for the organization to recognize and stay current on the differences. Many employers operate in more than one state and/or have individual employees who work in more than one state. This adds even more complexity that the Workforce Asset Management Professional (WAM-Pro) should consider during system design and administration. Workforce management (WFM) systems are the place where regulations materialize and influence how workers are managed and compensated. This chapter is an overview and discussion of some wage and hour topics, offering examples and configuration tips. In addition, there are exceptions to regulations, so employers should check with the state agencies that provide information on their rules to assess their individual compliance requirements.

- Recognize the differences between federal and state regulation, and know which should be followed during configuration.

- Know how to use wage orders as a source for determining state labor regulations.

- List the pros and cons of using weekly, biweekly, semimonthly, monthly pay periods.

- Describe the reasons why or why not to use automatic docking for meals or rest breaks.

- Identify how some states differ from the federal regulations on tracking time worked.

7.1 STATE WAGE AND HOUR GUIDELINES

In the United States, regulations regarding the payment of employees come from two main sources—the federal government and the state government. The previous section covered the federal requirements under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA). This section discusses the state requirements.

Each state can have its own set of laws in addition to federal requirements for such items as minimum wage, overtime, definition of hours worked. The state may match the federal standards, may be higher or lower than the federal requirements, or may even have no provisions governing a certain area of the law. It is strictly up to the state. There are also some areas of wage and hour law that the federal regulations do not cover and these areas are normally under the state's jurisdiction. These areas include meal periods, rest periods, and frequency of wage payments.

It is important to remember that when a conflict exists between state law and the FLSA, the law establishing the higher standard applies. Employers with collective bargaining agreements must also remember that such an agreement may contain wage and hour requirements that impose a higher standard than federal or state laws. In that event, the requirements of the collective bargaining agreement will prevail.

7.2 WAGE ORDERS

Unlike the federal regulations, which are contained within the Code of Federal Regulations, state requirements may be found in sources other than the state labor code. The most common source is known as a wage order. The state labor board for certain industries often issues wage orders or category of worker and its requirements can differ from the state's main requirements. To correctly pay an employee, it is necessary to determine if a state has any wage orders and which employees would be covered under its requirements. States that have some type of wage order include:

| State | Requirement |

| CA | The Industrial Welfare Commission (IWC herein after) issues the wage orders in California. The IWC wage orders govern wages, hours, and working conditions in California. The Division of Labor Standards Enforcement (DLSE) enforces the provisions of the wage orders. There are 17 Industrial and Occupational Wage Orders: #1. Manufacturing Industry #2. Personal Services Industry #3. Canning, Freezing, and Preserving Industry #4. Professional, Technical, Clerical, Mechanical, and Similar Occupations #5. Public Housekeeping Industry #6. Laundry, Linen Supply, Dry Cleaning, and Dyeing Industry #7. Mercantile Industry #8. Industries Handling Products After Harvest #9. Transportation Industry #10. Amusement and Recreation Industry #11. Broadcasting Industry #12. Motion Picture Industry #13. Industries Preparing Agricultural Products for Market, on the Farm #14. Agricultural Occupations #15. Household Occupation #16. Certain On-Site Occupations in the Construction, Drilling, Logging, and Mining Industries #17. Miscellaneous Employees |

| CO | The Colorado Minimum Wage Order (Number 28 for 2012) regulates overtime, meal and rest periods, tips and gratuities, uniforms, and record keeping for four major industries. These industries are: 1. Retail and Service 2. Commercial Support Service 3. Food and Beverage 4. Health and Medical The Colorado Division of Labor promulgates the Wage Order. |

| CT | Connecticut has regulations that cover specific industries. These include: 1. Mandatory Orders 7A & 7B which apply to the Mercantile Trade 2. Mandatory Order No. 8 which applies to persons employed in the restaurant and hotel restaurant occupations 3. Dry cleaning 4. Laundry 5. Beauty shops |

| DC | No longer in effect |

| NJ | New Jersey has seven wage orders for various industries. These include: 1. Wage Order No. 1 (MW 104) for First Processing of Farm ProductOccupations 2. Wage Order No. 2 (MW-72) Governing Employment in Seasonal Amusement Occupations 3. Wage Order No. 3 (MW 54) Governing Employment in Hotel and Motel Occupations 4. Wage Order No. 11 (MW 83) Mercantile Occupations 5. Wage Order No. 12 (MW 238) Beauty Culture Occupations 6. Wage Order No. 13 (MW 121) Laundry, Cleaning, and Dyeing Occupations 7. Food Serviced Occupations Regulations (MW 278) The Department of Labor and Workforce Development enforce the wage orders. |

| NY | New York has several wage orders for various industries. These include: 1. Hospitality Wage Order Covering Restaurant and Hotel Industries 2. Minimum Wage Order for Farm Workers 3. Building Services Industry Minimum Wage Order 4. Minimum Wage Order for Miscellaneous Industries and Occupations The provisions in the wage orders are enforced by the Department of Labor, Labor Standards Division. |

| WI | In Wisconsin there are minimum wage rates that apply specifically to camp counselors and caddies. |

7.3 DEFINITION OF OVERTIME

Each state may have its own method or regulations concerning the calculation of overtime. In addition, many states vary on the number of hours required to work before overtime must be paid. If the state has a less strict requirement than the FLSA, such as Kansas, which requires overtime to be paid after 46 hours of work in a workweek, an employer covered under the FLSA would ignore the state requirement and follow the FLSA. However, if the state has a stricter definition of overtime than what is required under the FLSA, the employer must follow the stricter requirement. The following states have overtime requirements that exceed the FLSA.

(a) Alaska

Under Sec. 23.10.060 of the Alaska Labor Code an employer who employs employees engaged in commerce or other business or in the production of goods or materials in the state may not employ an employee for a workweek longer than 40 hours or for more than eight hours in a day. If the employer finds it necessary to employ an employee for hours in excess of the limits, overtime compensation at the rate of one and one-half times the regular rate of pay shall be paid. When determining the number of hours worked per workweek, it shall be determined without including the hours that are worked in excess of eight hours in a day because the employee has or will be separately awarded overtime based on those hours. This section is considered included in all contracts of employment.

The overtime requirements do not apply to an individual working for an employer that engages less than four workers in the regular course of business.

The overtime requirements also do not apply to certain classification of employees, including but not limited to:

- Employees who handle agricultural or horticultural commodities for market or who make cheese, butter, or other dairy products.

- Employees engaged in small mining operations where there are 12 or fewer employees.

- Employees engaged in agriculture.

- Employee employed as a seaman.

There are other classifications of employees not listed here who are not covered under the overtime rule. The employer would need to inspect the employee's classification to determine proper payment of overtime. It is also permitted for the employer and the employee to enter into written agreement to permit a 10-hour day/40-hour week flexible schedule.

(b) California

In California, the general overtime provisions are that a nonexempt employee 18 years of age or older, or any minor employee 16 or 17 years of age who is not required by law to attend school and is not otherwise prohibited by law from engaging in the subject work, shall not be employed more than eight hours in any workday or more than 40 hours in any workweek unless he or she receives one and one-half times his or her regular rate of pay for all hours worked over eight hours in any workday and over 40 hours in the workweek. Eight hours of labor constitutes a day's work, and employment beyond eight hours in any workday or more than six days in any workweek is permissible provided the employee is compensated for the overtime at not less than:

- One and one-half times the employee's regular rate of pay for all hours worked in excess of eight hours up to and including 12 hours in any workday, and for the first eight hours worked on the seventh consecutive day of work in a workweek.

- Double the employee's regular rate of pay for all hours worked in excess of 12 hours in any workday and for all hours worked in excess of eight on the seventh consecutive day of work in a workweek.

There are, however, a number of exemptions from the overtime law. An exemption means that the overtime law does not apply to a particular classification of employees. There are also a number of exceptions to the general overtime law stated earlier. An exception means that overtime is paid to a certain classification of employees on a basis that differs from that stated earlier.

It is also permitted for employers and employees to agree to a flexible work schedule of 10 hours per day or 40 hours per week without the payment of overtime.

(c) Colorado

Employees who are covered by Colorado Minimum Wage Order (Number 28 for 2012) may, in certain circumstances, qualify for overtime pay. The following information only applies to nonexempt employees covered by the wage order:

Employees shall be paid time and one-half of the regular rate of pay for any work in excess of: (1) forty hours per workweek; (2) twelve hours per workday, or (3) twelve consecutive hours without regard to the starting and ending time of the workday (excluding duty free meal periods), whichever calculation results in the greater payment of wages.2

(d) Nevada

Generally, in Nevada, an employer must pay time and one-half of an employee's regular wage rate whenever an employee works more than 40 hours in any scheduled workweek. In addition, employees who are paid a base rate of one and one-half times the minimum wage or less per hour may be entitled to overtime if they work more than eight hours in any workday. There are a number of exemptions to this rule, and federal wage and hour rules may apply. See NRS 608.018 for more information on exemptions.

(e) Kentucky

Under KRS 337.050:

Any employer who permits any employee to work seven days in any one workweek shall pay the rate of time and a half for the time worked on the seventh day. For the purposes of this subsection, the term “workweek” shall mean a calendar week or any other period of seven consecutive days adopted by the employer as the workweek with the intention that the same shall be permanent and without the intention to evade the overtime provision set out herein. The above shall not apply in any case, in which the employee is not permitted to work more than forty hours during the workweek. It also does not apply to certain classes of employees, including: telephone exchanges having less than five hundred (500) subscribers, nor to stenographers, bookkeepers, or technical assistants of professions such as doctors, accountants, lawyers, and other professions licensed under the laws of this state, nor to any employees subject to the Federal Railway Labor Act and seamen or persons engaged in operating boats or other water transportation facilities upon navigable streams, nor to persons engaged in icing railroad cars, nor to common carriers under the supervision of the Department of Vehicle Regulation. It also does not apply to any officer, superintendent, foreman, or supervisor whose duties are principally limited to directing or supervising other employees.

(KRS 337.050 is the note for the law that this comes from: http://www.lrc.ky.gov/krs/337-00/050.PDF. The history noted on the PDF can be found here: Amended 1974 Ky. Acts ch. 28, sec. 1; and ch. 74, Art. IV, sec. 20(2). Recodified 1942 Ky. Acts ch. 208, sec. 1, effective October 1, 1942, from Ky. Stat. sec. 1599c-20.)

(f) Oregon

State law sets 10 hours as a maximum that employees may work in one day in mills, factories, or manufacturing establishments. The law, however, does allow for an additional three hours of work per day to be paid at one and one-half times the regular rate of pay. The maximum daily number of hours of work allowed may not exceed 13. Logging camps, sawmills, planning mills, and shingle mills are excluded from this requirement.

Adults working in canneries must be paid at one and one-half times their regular rate of pay whenever they work more than 10 hours per day or 40 hours in one seven-day workweek. Whenever overtime is being calculated on a daily basis, it also must be calculated on a weekly basis. The greater of the two amounts is the one to be paid.

(g) Multiple State Situations

When an employee performs work in two or more states it becomes necessary to make sure that regulations for the state where the work is performed are followed, especially if that state requires overtime different than the FLSA and/or other work states. For example:

- Employee S works in both California and Arizona for Company W.

- Monday and Tuesday of the workweek Employee S worked nine hours per day in California.

- Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday Employee S worked nine hours per day in Arizona.

- Saturday, Employee S returned to California and worked 13 hours for a total of 58 hours.

Under the FLSA the overtime premium would be calculated for 18 hours. Since Arizona follows federal law, no change there. But because California has different rules the time worked there follows the daily overtime/double time rules for California. The result would be calculated as follows:

The total time owed the employee would be: 40 straight, 17 OT, and 1 DT.

7.4 DEFINITION OF WORKWEEK AND WORKDAY

Under the FLSA the employer is permitted to set up the workweek, as it needs in order to meet the requirements of the business. It consists of 168 consecutive hours—seven 24-hour periods. It is fixed and finite. The states, if there is a regulation, will generally follow this same rule.

The definition of the workday under the FLSA is a little less clear. It states that there are seven 24-hour periods in the workweek so from that it can be inferred that a workday is one 24-hour period.

The state, however, may actually codify or provide a definition of workday. For example: Nevada defines the workday in NRS 608.0126 as a period of 24 consecutive hours, which begins when the employee begins work. But California follows the more generally accepted FLSA definition of workday in Labor Code 500(a), which defines workday as any consecutive 24-hour period commencing at the same time each calendar day. It is important to determine the definition of the workday when paying the employee.

7.5 FREQUENCY OF WAGE PAYMENTS

The pay date is defined as “the effective date of paychecks (not the day the payroll is processed, payments are transferred to bank accounts or checks are mailed).”

In the area of frequency of wage payments, there is no requirement under the FLSA. It is left strictly up to the states. There are four common frequencies that a state can choose to permit:

When the state permits multiple pay frequencies it is up to the employer to choose the frequency that best suits the needs of the company and its employees. There are various pros and cons for each type of pay frequency as explained in Table 7.1.

Table 7.1 Pay Frequency Pros/Cons Matrix

| Pay Frequency | Pros | Cons |

| Weekly |

|

|

| Biweekly |

|

|

| Semimonthly |

|

|

| Monthly |

|

|

Under the state laws, 44 states and the District of Columbia have a requirement that employees must be paid within a certain frequency such as semimonthly or weekly. Alabama, Florida, North Carolina, and South Carolina have no exact requirements. The laws of Alabama and Florida are totally silent on the issue. The laws of North Carolina have no specifications but do permit any frequency. In South Carolina the law requires an employer with five or more employees to establish a normal time and place of payment. In Nebraska and Pennsylvania the employer is permitted to choose the pay frequency.

Many of the states such as California, Michigan, or New York regulate the frequency of wage payments based on the occupation of the employee while some states such as Minnesota and Louisiana base it on the business of the employer.

No state forbids an employer from paying earlier than the requirements. For example, Delaware requires employees to be paid monthly. The state would not restrict an employer from paying its employees in Delaware on a biweekly or semimonthly payroll frequency.

For multistate employers, all states where it has employees located must be taken into consideration when determining the pay frequency used by the company. For example, a company with employees in Alaska and California would be in compliance by choosing the biweekly pay frequency since both states permit that. But if the company also had employees in Connecticut, which requires a pay frequency of weekly, that may pose a problem unless the employer were able to acquire permission from the Labor Commissioner in Connecticut to pay semiweekly.

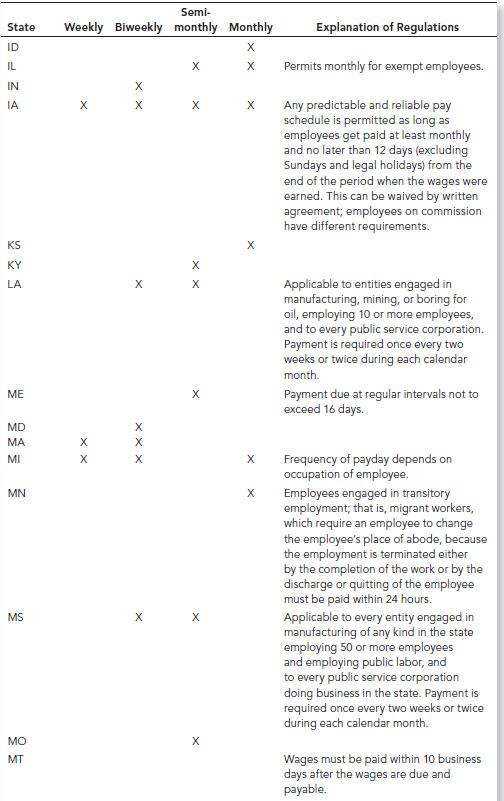

Table 7.2 lists the frequency of payment requirements for all 50 states and the District of Columbia.

Table 7.2 Pay Frequency Provisions by State

(a) Lag Time

In addition to payroll frequencies, the state may also regulate what is known as lag time. The time between the date the payroll is closed (timecards are completed for the pay period) and the date the employee is actually paid. This would be commonly viewed as the payroll processing time. Just because two states have the same payroll frequency does not mean they have the same lag time. For example, Tennessee, which requires a semimonthly pay frequency, dictates the following lag time:

- All wages or compensation earned and unpaid prior to the first day of any month shall be due and payable not later than the 20th day of the month following the one in which the wages were earned.

- All wages or compensation earned and unpaid prior to the 16th day of any month shall be due and payable not later than the fifth day of the succeeding month.

Tennessee therefore permits a 20-day lag or processing time for the employer. However, Ohio, which also requires a semimonthly pay frequency, states:

Every employer doing business in the state shall, on or before the first day of each month, pay all its employees the wages earned by them during the first half of the preceding month ending with the fifteenth day thereof, and shall, on or before the fifteenth day of each month, pay such employees the wages earned by them during the last half of the preceding calendar month.3

Based on this regulation Ohio, though still semimonthly, only permits a 15-day lag time for processing the payroll. It is imperative when implementing, maintaining, or changing the payroll frequency the employer must take into account the lag time requirements for each state where the employee is working to remain compliant.

(b) Changing Payroll Frequencies

Changing payroll frequencies is permitted by the states in most cases unless it is done strictly for the purpose of avoiding overtime already worked. It is an arduous task and should be approached with care and a tremendous amount of research and preparation. The compliance issues that need to be addressed before making the decision to change payroll frequency include:

- Does the state permit the frequency?

- Will the state allow the frequency based on the lag time between the end of the pay period and the pay date?

- Are there any employee notifications required prior to the change being made?

In addition to compliance issues, there are issues that deal with timing, systems, and employee earnings and fringe benefit accruals. For example, deciding when to implement the pay frequency can impact a myriad of issues. If it is done prior to January 1 what is the impact on issuing the Forms W-2? If not done on January 1 what will be the impact on salaried employees? Fringe benefits such as vacation or sick leave accruals are affected by a payroll frequency change if they are calculated based on a time frame such as per pay period. These items and many more must be addressed prior to implementing a payroll frequency change.

7.6 MEAL PERIODS

It is a common company policy to permit employees to take a meal periods during their shift. Therefore a common misperception is that a lunch period is mandated for all employees working in the United States. This is not true; under the FLSA no meal period is required for any employee. However, 20 states do have a regulation that requires the employer to give or permit the adult employee to take a certain amount of time off to eat lunch during the employee's shift.

The average time is usually 30 minutes and the time is usually unpaid or off the clock. Many of the states specify the meal period must take place after a certain passage of time in the shift. For example, Oregon and Tennessee require a meal period after six hours, while California and Colorado meal periods are after five hours. Table 7.3 contains the meal period requirements for each of the states that require one.

Table 7.3 Meal Period Requirements by State

| State | Requirements |

| CA | In California, an employer may not employ an employee for a work period of more than five hours per day without providing the employee with a meal period of not less than thirty minutes, except that if the total work period per day of the employee is no more than six hours, the meal period may be waived by mutual consent of both the employer and employee. A second meal period of not less than thirty minutes is required if an employee works more than ten hours per day, except that if the total hours worked is no more than 12 hours, the second meal period may be waived by mutual consent of the employer and employee only if the first meal period was not waived. Labor Code Section 512. There is an exception for employees in the motion picture industry, however, as they may work no longer than six hours without a meal period of not less than 30 minutes, nor more than one hour. And a subsequent meal period must be called not later than six hours after the termination of the preceding meal period. IWC Order 12–2001, Section 11(A) |

| CO | Employees shall be entitled to an uninterrupted and duty-free meal period of at least a 30-minute duration when the scheduled work shift exceeds five consecutive hours of work. The employees must be completely relieved of all duties and permitted to pursue personal activities to qualify as a nonwork, uncompensated period of time. When the nature of the business activity or other circumstances exists that makes an uninterrupted meal period impractical, the employee shall be permitted to consume an on-duty meal while performing duties. Employees shall be permitted to fully consume a meal of choice on the job and be fully compensated for the on-duty meal period without any loss of time or compensation. |

| CT | The half hour after the first two hours and before the last two hours for employees who work 7½ consecutive hours or more. Excludes employer who provides 30 or more total minutes of paid rest or meal periods within each 7½-hour work period. Meal period requirement does not alter or impair collective bargaining agreement in effect on 7/1/90, or prevent a different schedule by written employer/employee agreement. Labor Commissioner is directed to exempt by regulation any employer on a finding that compliance would be adverse to public safety, or that duties of a position can be performed only by one employee, or in continuous operations under specified conditions, or that employer employs less than five employees on a shift at a single place of business provided the exemption applies only to employees on such shift. |

| DE | All employees must receive a meal break of at least 30 consecutive minutes if the employee is scheduled to work 7.5 or more hours per day. Meal breaks must be given sometime after the first two hours of work and before the last two hours of work. Rules have been issued granting exemptions when: 1. Compliance would adversely affect public safety. 2. Only one (1) employee may perform the duties of a position. 3. An employer has fewer than five (5) employees on a shift at one location (the exception would only apply to that shift). 4. The continuous nature of an employer's operations, such as chemical production or research experiments, requires employees to respond to urgent or unusual conditions at all times and the employees are compensated for their meal breaks. Where exemptions are allowed, employees must be allowed to eat meals at their work stations or other authorized locations and use restroom facilities as reasonably necessary. |

| IL | Each hotel room attendant—those persons who clean or put guest rooms in order in a hotel or other establishment licensed for transient occupancy—shall receive one 30-minute meal period in each workday in which they work at least seven hours. |

| KY | Employers, except those subject to the federal Railway Labor Act, shall grant their employees a reasonable period for lunch, and such time shall be as close to the middle of the employee's scheduled work shift as possible. In no case shall an employee be required to take a lunch period sooner than three hours after the work shift commences, nor more than five hours from the time the work shift commences. |

| ME | Employers must give employees the opportunity to take an unpaid rest break of 30 consecutive minutes after six hours worked if three or more people are on duty. An employee and employer may negotiate for more or less breaks, but both must agree (this should be put in writing). |

| MA | No person shall be required to work for more than six hours during a calendar day without an interval of at least 30 minutes for a meal. |

| MN | An employer must permit each employee who is working for eight or more consecutive hours sufficient time to eat a meal. |

| NE | Any person, organization, or corporation owning or operating an assembling plant, workshop, or mechanical establishment employing one or more persons shall allow all of their employees not less than 30 consecutive minutes for lunch in each eight-hour shift, and during such time it shall be unlawful for any such employer to require such employee or employees to remain in buildings or on the premises where their labor is performed. This section does not apply to employment that is covered by a valid collective-bargaining agreement or other written agreement between an employer and employee. |

| NV | An unpaid meal period of 30 minutes of uninterrupted time shall be authorized for an employee working a continuous period of eight hours. |

| NH | An employer cannot require that an employee work more than five consecutive hours without granting a 30-minute lunch or eating period. If the employer cannot allow 30 minutes the employee must be paid if they are eating and working at the same time. |

| NY | 1. Every person employed in or in connection with a factory shall be allowed at least 60 minutes for the noonday meal. 2. Every person employed in or in connection with a mercantile or other establishment or occupation coming under the provisions of this chapter shall be allowed at least 30 minutes for the noonday meal, except as in this chapter otherwise provided. The noonday meal period is recognized as extending from eleven o'clock in the morning to two o'clock in the afternoon.An employee who works a shift of more than six hours, which extends over the noonday meal period, is entitled to at least 30 minutes off within that period for the meal period. 3. Every person employed for a period or shift starting before eleven o'clock in the morning and continuing later than seven o'clock in the evening shall be allowed an additional meal period of at least 20 minutes between five and seven o'clock in the evening. 4. Every person employed for a period or shift of more than six hours starting between the hours of one o'clock in the afternoon and six o'clock in the morning, shall be allowed at least 60 minutes for a meal period when employed in or in connection with a factory, and 45 minutes for a meal period when employed in or in connection with a mercantile or other establishment or occupation coming under the provision of this chapter, at a time midway between the beginning and end of such employment. |

| NY | 5. The commissioner may permit a shorter time to be fixed for meal periods than hereinbefore provided. The permit therefore shall be in writing and shall be kept conspicuously posted in the main entrance of the establishment. Such permit may be revoked at any time. One-employee shift: In two cases, it is customary for the employee to eat on the job without being relieved. This applies where: 1. Only one person is on duty. 2. There is only one person in a specific occupation. If the employee volunteers to accept this arrangement, the Department of Labor will accept these special situations as compliance with Section 162. However, an employer must offer an uninterrupted meal period to every employee who asks for one. |

| ND | A minimum of 30-minute meal period must be provided in shifts exceeding five hours when there are two or more employees on duty. Employees may waive their right to a meal period on agreement with the employer. Employees do not have to be paid for meal periods if they are completely relieved of duties and the meal period is at least 30 minutes in length. Employees are not completely relieved of duties if they are required to perform any duties during the meal period. |

| OR | Meal periods of not less than 30 minutes must be provided to nonexempt adult employees who work six or more hours in one work period. Ordinarily, employees are required to be relieved of all duties during the meal period. Under exceptional circumstances, however, the law allows an employee to perform duties during a meal period: When that happens, the employer must pay the employee for the whole meal period. With the exception of certain tipped food and beverage service workers, meal periods may not be waived and may not be used to adjust working hours. |

| RI | A 20-minute meal period must be given during a six-hour shift, and a 30-minute meal period must be given during an eight-hour shift. This does not include health-care facilities or companies employing less than three employees at one site during a shift. |

| TN | State law requires that each employee scheduled to work six consecutive hours must have a 30-minute meal or rest period, except in workplace environments that by their nature of business provides for ample opportunity to rest or take an appropriate break. |

| VT | Under Vermont law, an employer must provide its employees with reasonable opportunity to eat and use toilet facilities to protect the health and hygiene of the employee. Federal law mandates that if an employer provides a lunch period, it is counted as hours worked and must be paid unless the lunch period lasts at least 30 minutes and the employee is completely uninterrupted and free from work. |

| WA | If more than five hours are worked in a shift:

|

| WA |

Workers may give up their meal period if they prefer to work through it and if the employer agrees. Business owners please note: The Department of Labor and Industries recommends that you get a written statement from workers who want give up their meal periods. |

| WV | In 1994, the State Legislature approved and enacted Article 3, Safety and Welfare of Employees, (21–3-10a Meal Breaks). This section of the WV State Code states that “During the course of a workday of six or more hours, all employers shall make available at least twenty minutes for meal breaks, at times reasonably designated by the employer. This provision shall be required in all situations where employees are not afforded necessary breaks and/or permitted to eat while working.” |

In addition to the above requirements 33 states have separate provisions requiring meal periods for minors. Some of the states do not have a provision other than for minors. The states that have either a separate meal provision or a stand-alone meal provision that applies only to minors include: Alabama, Alaska, California, Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Hawaii, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Utah, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, and Wisconsin.

(a) Automatic Docking for Meal Periods

Regardless if the meal period is provided as part of the company policy or based on state law it is usually an unpaid period and must be tracked in the timekeeping system. Both state and federal law provide that if a period of 20 minutes or longer is given for a break it can be unpaid. In decades past the employee was required to punch out and punch in to demonstrate that the meal period had been taken. With the modern electronic timekeeping systems it is possible to program an automatic deduction for the lunch period to be recorded on the employee's timecard each day.

This is certainly a much more time-efficient method in tracking the hours. It takes care of the hassles of employees who forget to punch out and punch back in. But it is also an efficient way to underpay an employee who did not take the lunch period to begin with. Careful attention must be paid to lunch periods that are done automatically to make sure that the time was actually taken for the break. The employer must clearly define who is responsible for monitoring the lunch period—supervisors, employees, managers, or payroll—and make sure that if it is docked it was indeed taken.

(b) Interrupted Meals

In states that require a meal period, it normally requires that it be uninterrupted time. In other words, the employee must be free from all normal duties for the entire period. Under the FLSA the employer can only dock for the meal period if the employee is again free from all duties. So what happens if the employee who is on lunch is called back in to work, even for only a few moments?

Basically once the employee is required to perform his or her duties, no matter how slight or how quickly, the lunch period has ended and that employee is back on the clock and working. If a minimum of 20 minutes has not elapsed, the employer would then have the choice, if the state permits it, of simply paying the employee for a working lunch for that day. But many states do not permit working lunches—example California. If this were to occur in California the employer would be mandated to pay the employee an additional hour's pay for that day as a penalty for the employee skipping lunch.

If 20 minutes has indeed elapsed, the employer could dock the employee for that time and have the employee return to work as under the FLSA and states without a meal period requirement this would be permitted. However, because most states with a meal period requirement, such as Washington, require a minimum of 30 minutes, again under state law this would not be permitted. To facilitate total compliance the employer could permit the employee to begin the lunch period again. Not resume, but begin with a full 30 minutes or more (depending on state law or company policy) permitted.

No matter what the resolution to the interrupted lunch the employee must be sure to record the time returned to work for the interruption and the time returned to the meal period, if that occurs.

7.7 REST PERIOD

In addition to or in place of meal periods, nine states mandate that an employee be provided with a rest period or break during the day. And again, this is also a common company policy. But unlike meal periods, rest periods or breaks are usually of so short a duration (less than 20 minutes) that they must be provided on the clock or are compensated time. The break is usually 10 minutes net rest and is to be provided in the middle of the shift as possible. Table 7.4 lists the mandated breaks required by states.

Table 7.4 State Mandated Rest Breaks

| State | Additional Requirements or Applications |

| California | Not required if total daily work time is less than 3½ hours |

| Colorado | Applies to workers covered under wage order |

| Illinois | Applies to hotel room attendants |

| Kentucky | Must be in addition to meal period |

| Minnesota | Time to use the nearest restroom must be provided within each four consecutive hours of work |

| Nevada | Not required if total daily work time is less than 3½ hours |

| Oregon | Must be in addition to meal period |

| Vermont | Employees are to be given reasonable opportunities during work to eat and use toilet facilities |

| Washington | May not be required to work more than three hours without a rest period |

7.8 DEFINITION OF HOURS WORKED

As under the FLSA, the state may provide a definition of what it considers hours worked, time the employee must be compensated for. In most cases the basic definitions the state provides follows the FLSA. However, some states will require payment for what could be called specialty payments particular to that state or not mentioned under the FLSA. It is also possible that the state's definition of a particular type of payment is stricter than the FLSA due to either state law or court cases decided within that state's jurisdiction.

Because of this it is imperative that an employer determine the definition of hours worked and any specialty payments under each state jurisdiction when paying an employee for work performed in that state. It would be impossible to list all of the definitions of hours worked for all of the states within this manual. However, here are examples of payments that may be different or need research:

- Specialty payments such as reporting time pay, show up pay, or shift differential. Some states require that an employee who shows up for work when requested but is denied any work to perform must be paid for a minimum amount of time. In California, is this known as reporting time pay? The employee must be paid at least half of the normal shift the employee would have worked but no more than four hours and no less than two hours. This also applies when an employee is called back into work after completing a shift. The employee must either work a minimum of two hours or be paid a minimum of two hours when asked to return to work.

- On-call pay. The state may follow the federal rules or have their own requirements. This type of pay is very tricky as it depends on the actual facts of each case such as distance traveled, restriction on use of personal time, and so on. It may also depend on if the state has a history of court cases that affect the state's interpretation of the wage and hour law.

- Travel pay. The federal law on travel pay generally requires the travel time to occur or cross during the employee's normal working hours in order to be considered compensation. This is not necessarily the case on the state level. For example, again in California, it does not matter what time of day the employer required travel occurs; it is compensated time, as is the ride to the airport, check in, and the plane flight.

- Meetings and training. Any required meeting or training is going to be considered time worked on both the federal and state level. It does not matter if the training occurs live on the employer's premises, live at an off-site location such as a hotel meeting room, or remotely using the employee's home computer after normal working hours. Any time the employee is required to attend a meeting or training it is hours worked and must be compensated.

- Sleeping time. The FLSA usually determines if the length of the employee's shift compensates sleep time. If fewer than 24 hours, all duty time is probably hours worked even if the employee is permitted to sleep. If more than 24 hours then a bona fide sleep period of eight hours may be agreed to. The states usually follow this same situation when enforcing payment for sleeping.

- Shift work and its effect on timekeeping. Company policy usually dictates if an employee working on a second or third shift receives extra compensation. However, the difficulty for timekeeping as it applies to shift work usually occurs when attempting to determine which workday and/or workweek the hours should be applied to determine payment or especially overtime. Strict policies must be in place to explain how the workday and/or work is determined for employees whose normal shift crosses either the normal midnight delineation of a day or the employer's established definition of the end of the workday or beginning of a new workweek.

- Volunteering of hours. The states generally follow the federal definition of when and how employees may volunteer hours for charity work sponsored by the employer.

- Rules for telework or off-premises time reporting. Telecommuting is a new concept being applied to employees and the states are just beginning to address the issue. In most cases the main questions concern the taxation of the compensation—which state controls the withholding of income tax if the employee telecommutes between two states and whether a telecommuter could be classified as an independent contractor. But wage and hour laws are starting to be a concern as well. One of the first states to address the issue is Colorado, which states:

Telecommuting, or telework, is a work arrangement by which an employee performs job duties from an alternate location that is outside the traditional workplace. Telecommuters are still subject to the control and direction of their employer, and are classified as employees; the fact that a telecommuter does not report to an office is not sufficient to allow the employer to categorize the telecommuter as an independent contractor.

As with more traditional employees, telecommuters must be paid for all of the work they perform. Allowing non-exempt employees to telecommute may raise special issues for the employer. The employer should devise, install, or utilize some method to track employee work in an accurate and timely fashion. If the employer does not use a formal tracking system for time worked (for example, login time on a computer), then the employer may be obligated to pay for all time worked as recorded and submitted by the employee.

As Colorado points out, one of the greatest concerns with telecommuting employees is to determine that the hours are recorded correctly to make certain of proper payment, especially for overtime.

7.9 TRACKING HOURS WORKED

Under the FLSA the only requirement for tracking hours worked is to make sure that the employer keeps full and methodical timekeeping records. The states usually go further in this area by requiring that the employer keep specific records for each employee. For example, New Hampshire actually addresses electronic timekeeping systems and requires the following when it comes to recording hours worked:

- The time records show the time work began and ended, including any bona fide meal periods.

- The time records must not be altered unless the entry is signed or initialed by the employee whose record was altered.

- An employer may not make use of an automated timekeeping device or software program that can be altered by an employer without the knowledge of the employee or that does not clearly indicate that a change was made to the record.

- The employer must make such good records as shall show the exact basis of remuneration of an employee's compensation.

Likewise, California requires that the employer keep specific information showing when the employee begins and ends each work period as well as recording each meal period and split-shift intervals but does not discuss the type of system to be used. Wisconsin requires that employers record the beginning and ending of work each day and the beginning and ending of each meal period if it is to be deducted from work time.

Proper recording of the employee's time is an essential part of record keeping to make certain that the proper payment of hours worked and the states have and are addressing this issue. Careful research must be done for each state where the employer has employees to assist in full compliance. And as mentioned earlier the states are beginning to look at electronic timekeeping systems and the issues that are raised with their use.

(a) Salaried Nonexempt Employees

Fixed workweek: The states usually follow the same regulations as the FLSA when it comes to paying nonexempt employees a salary on a fixed workweek basis. However, because the employee is subject to overtime, accurate time records must be kept.

Fluctuating workweek: Not all states accept this method of paying a nonexempt employee on a salary basis. California does not permit employers to use this method whatsoever. An employer would need to verify if the state in question permits fluctuating workweeks for salaried nonexempt employees. But again, this type of employee is subject to overtime and specific timekeeping records must be maintained.

For example, Rhode Island has the following requirements concerning tracking hours:

An employer must keep an accurate daily and weekly (time in and out) record for all employees. No one, including employees paid on a salary basis, is exempt from this law. These records, along with payroll records, must be kept for at least three years.4

(b) Exempt Punching

States that address the issue of exempt employees may do so in the following ways: the state can follow the current federal rules, follow the pre-2004 federal rules, or have their own rules. No state prohibits employers from having exempt employees record working hours as long as the timekeeping is not used in direct connection with paying the employee.

The WAM-Pro relies on an understanding of both federal and state regulations and applies configuration tools to accurately compute and report work activity that states care about. For those WAM-Pros that manage WFM systems covering a multistate workforce, this job is even more complex when employees work in more than one state.

NOTES

1. Colorado Department of Labor and Employment, “Overtime: Overtime Hours,” last modified 2012, www.colorado.gov/cs/Satellite/CDLE-LaborLaws/CDLE/1248095305395.

2. Ohio Revised Code, “4113.15 Semimonthly Payment of Wages,” Title 41: Labor and Industry, Chapter 4113: Miscellaneous Labor Provisions (1974), http://codes.ohio.gov/orc/4113.15.

3. Rhode Island Department of Labor and Training, “Frequently Asked Questions about RI's Wage and Hour Law,” A Guide to Workforce Regulation and Safety Division Labor Standards. (Wage and Hour) Unit 1511, Pontiac Avenue, Cranston, RI 02920 Tel: (401) 462-8550, Fax: (401) 462-8530, www.dlt.ri.gov/ls; Wage and Workplace Laws Rhode Island, February 2011, www.dlt.ri.gov/ls/pdfs/wagehourbook.pdf.

4. This chapter was contributed by Vicki Lambert.