CHAPTER TEN

Scheduling Drivers and Design1

IN THIS CHAPTER, THE FUNDAMENTALS of workforce scheduling are explored, including types of schedules, how schedules are created, and how that translates into WFM scheduling system design and deployment. Historically, the science of scheduling has not been studied, taught, or institutionalized in many organizations. Scheduling methods are often individual art forms, designed around interpersonal relationships, and frequently executed with little consideration of the resulting labor costs. Today's WFM systems enable organizations to incorporate the key business drivers into the process of forming and adjusting schedules in real time. The right WFM scheduling application depends on the highly specialized schedule demands and constraints of the organization which determine how the workload can be assigned.

- Explain the concepts of workforce scheduling.

- Explain the scheduling process and its breakdown.

- Select the appropriate scheduling process for different business types.

- Interpret business operations to identify key elements that influence a schedule.

- Select the appropriate key performance indicators (KPI) that support scheduling decisions.

- Collect and document key scheduling requirements for a scheduling software targeting different business types.

Workforce scheduling is a complex process that assigns working hours to the workforce. Although scheduling is crucial to business operations, it is often misunderstood or undermined. Organizations from different industries operate differently and therefore schedule for their particular needs using industry-specific terminology. But the basics are the same: meet business demand at low cost and high productivity. A workforce schedule is the match between business demand and workers. At a high level, scheduling is often seen as an operational problem that should be solved within operations. But reality shows that management levels within many departments of a business have some sort of influence on the workforce schedule: Human resources will dictate constraints (maximum hours of work per day, per week, maximum number of consecutive night shifts, etc.); finance will impose a budget; sales will propose an earlier deadline to a customer; and so on. These facts will funnel to the frontline manager who maintains the schedule to the best of his or her ability. That frontline manager is held accountable for cost and productivity; yet the constraints with a direct impact came from departments in and outside of operations.

In addition, a workforce schedule has one major varying component: the workforce. Employees can be productive one day and less productive the next day. Employees need rest, breaks, training, and so on. Employees have concerns outside of their job that influence their productivity and availability. These variables changing through time for each individual employee make the outcome of a schedule uncertain until it has actually been worked.

A schedule is therefore a plan, an intention, that dictates who does what, when, and where. These dimensions impose an ongoing decision-making process. One decision (e.g., shift start time) will open or close possibilities for the next decision (that shift's end time and who is available to work that shift). The result is an exponential number of possibilities, where each decision has an impact on the final schedule and therefore on its cost and productivity.

The complexity of scheduling also comes from its dynamic perspective. The notion of time is obviously essential in the scheduling world. Not only because a schedule is based on time, but also because a schedule is based on changing information over time. When a planner starts creating a schedule, the decisions are based on certain inputs (business demand, employee availability, etc.). The planner, by experience, knows that this information has a high probability of changing in the future. For example, when a schedule is created, a planner has a list of employees to schedule. That list of employees may change between the time the schedule is created and the time the schedule actually starts (e.g., a new employee is hired, another employee resigns, another employee has a promotion).

Schedules are part of the future until they are worked and become part of the past. The present is only the frontier between the past and the future and a multitude of external events influence that future. Scheduling is therefore a forever changing plan until it has completely crossed into the present frontier. As Greek philosopher Heraclitus said: “Change is the only constant.”

This chapter explains the different concepts and perspectives that are part of a schedule. The first section explains the three major concepts required in a schedule (workload, constraints, and workforce) and the scheduling process. This section documents the theory, but also focuses on the key elements that influence the selection of a scheduling process that fits a business model.

The second section offers different perspectives and examples from different industries. This section documents how each industry schedules and which process and terminology is generally in use. This section also highlights the peculiar operational situations in various industries that make scheduling problems different.

10.1 WORKLOAD

The definition of workload is the cornerstone of scheduling. A scheduling problem starts with breaking down the business demand into assignable hours of work. There are three parts to a workload:

(a) Identification

Identification begins with categorizing the activities and tasks by type and segmenting the work effort into simple terms.

i. Activity Breakdown

To get started, business demand must be broken down into words that can define an employee's intervention or activity. The selection of the vocabulary used for the breakdown is essential. The breakdown must be simple (one verb with one noun) and must relate to the business. The selected verbs need to relate to an action or an activity that an employee can perform (“Be productive” or “Make profits” are not action-based).

For example, a store's business demand can be expressed as serve customers. Breaking down serve customers would result in “Answer customer questions” and “Checkout”; Checkout would result in “Process payment” and “Bag items,” as shown in Figure 10.1.

Figure 10.1 Breakdown Example

Breaking down the business demand into activities can go at a very detailed level. A few rules of thumb can be followed to avoid going too low:

- Stop at the level where factual data is available. In the previous example, the store may be able to measure the amount of time it takes to check out a customer using its point-of-sales data but it may not be able to clearly state how much time is required to process the payment versus bagging items. This would make Level 3 too detailed.

- Stop at the point where the same person will perform all activities. In the example above, if the cashier performs both activities of Level 3 (process payment and bag items), that level is probably not required even if you have factual data. On the other hand, if the store would be a grocery store, Level 3 would be required because two different employees perform the activities of that level.

ii. Activity Type

Each activity listed has a relationship with time. The activity's occurrence in time will determine its type.

(A) Demand Driven

A demand-driven activity is required to happen at a specific moment in time. It is driven directly by an external event that requires immediate attention. Most of these activities have a direct relationship with business demand and fluctuates in time accordingly. For example, when a customer goes to the cash register to make a purchase, the expectation is to be served at that precise time.

A demand-driven activity is also one that needs to offer response capabilities or capacity at all times. Even though the actual time of executing the activity cannot be foreseen, the activity requires employees present and able to respond (e.g., law enforcement, first responders).

The demand-driven activities are the most common, and most scheduling software products are built around this type of workload.

(B) Task Driven

A task-driven activity is required to happen within a short time span but is not required to happen at a moment dictated by an external event. The definition of the short time span is usually within the same shift or day. Tasks will be handed out to employees at the beginning of their shift and the employee will perform the tasks when the business demand is lower (e.g., stocking shelves, completing a report, cleaning hallways).

Some industries keep track of these activities through work order systems. Most businesses that own buildings or equipment will have a maintenance department that manages work activities through work orders.

This type may also imply precedence where an activity is required to be completed before the next activity can occur. If precedence is required, the activity will generally be classified as Project Driven; activity precedence within scheduling processes increases the complexity and should be used cautiously.

(C) Project Driven

A project-driven activity is required to happen by a certain deadline. These activities are usually at a high level and have a low requirement for scheduling. The activity is assigned to an employee with a deadline date. It is the employee's responsibility to complete the activity by the deadline date and report on the activity's completion.

Although this type of activity is mostly used in an office environment, it does come up in scheduling processes when employees are assigned to special projects. If a highly skilled employee is taken out of operations to participate in a higher level initiative, this employee needs to be replaced and may remain part of the schedule if his or her assignment on the project is on a part-time basis.

(b) Quantification

Quantification starts with a measure of business demand. Any business demand has a unit of measure: customers, patients, work orders, and so on. A business can have many business demands and therefore many units of measure.

Each unit of business demand has a time precision or a time span on which the measure is available: X unit per Y hours.

Examples:

The available precision of business demand often dictates variables during the scheduling process. If an hourly breakdown is available, the related schedule could establish shift start times for every hour of the day. But if the precision is only available on an eight-hour time span, the schedule may be established on the same time spans and will therefore only have three different shift start times.

i. Forecasting

A schedule is produced for a future time span where in most cases the business demand for that time span is not known with certainty. This is the step where a crystal ball is required.

Forecasting is the projection of future business demand. These projections will be expressed in the same units and with the same time precision as the ones that were measured.

In most industries, forecasting is an art, and planners depend on their experience to determine what will be required for that future schedule. Other industries use high-end software to calculate projections based on past data.

In both cases, the business demand for a future time frame remains an estimate. The schedule produced is based on that estimate. A perfectly balanced schedule can be produced, but if the estimates are too high by just a fraction, actual productivity will be impacted.

ii. Labor Standards

Each unit of business demand implies one or multiple activities that are performed by one or more employees. Each activity therefore requires an estimated amount of time to serve or complete one unit, more commonly known as a Labor Standard or Labor Rate (not to be confused with Labor Standards used in legislation for employee working conditions). Using our store example, processing payment may take 90 seconds and bagging items may take 12 seconds on average for each customer. This example oversimplifies the concept but illustrates the goal of quantification: transform business units into time units.

Determining labor standards can be extremely detailed and complex. There are many different techniques to study work in order to break down and measure the steps of manual and repetitive tasks. These techniques, also referred to as predetermined motion time systems (PMTS), were initially put together in manufacturing environments. These techniques break down tasks to basic human motions (e.g., turn, grab, move). This breakdown is used not only to measure time for specific tasks, but it can also be used to rearrange the repetitive motions employees perform. Employee productivity is not only about time, but also about the value of the work that is done.

There are a multitude of techniques that exist (e.g., MTM: Methods-Time Measurement, MODAPTS: MODular Arrangement of Predetermined Time Standards, MOST: Maynard Operation Sequence Technique). Each business applies the one that corresponds to their goals. In most techniques, a coding standard is used for each motion an employee performs that is put together in a sequence. Using predetermined times for each motion (depending on the technique), the sequence becomes the labor standard.

The available software implementing these techniques can be precise, but also require trained specialists. If such a system is not in place in an organization, the first method of establishing a labor standard can be simple observation with a stopwatch. This method can at least give a ballpark value, but can go wrong quickly if some basic pointers are not followed:

- Be mindful of the goal that is to establish a workload for scheduling purposes. These measures should therefore be used in that context only. The numbers may not necessarily represent a specific study of optimal time or defined breakdown of tasks.

- Make sure that measuring takes place at different times of the day, on different days of the week, and with different employees.

- Measure from a distance so that the employees' performance is not influenced (positively or negatively) by the fact that they are aware of the measuring procedure.

The obvious downside to this approach is that the actual average measured time becomes the standard. There is no comparison to other businesses or to industry productivity standards.

In some contexts, labor standards are calculated from actual measured values available in other systems. For example, retail stores can determine the average time to process a customer from the cash register data. Although this avoids the manual stopwatch observation, it shares the same downside where the actual measure becomes the standard and does not necessarily compare to industry standards.

If a PMTS is in place, it should integrate to the WFM by sending the appropriate labor standards for each activity and/or task that requires scheduling. The planner can therefore rely on the same numbers established by the business. If the scheduling system is disconnected from the PMTS, the planner may depend on different standards to produce the schedule. The productivity calculated with the WFM system may be compared to expected productivity calculated with data from the PMTS. However, this would be comparing on two different bases and one may conclude that the planner produces bad schedules when the problem is the underlying data source. In some contexts, labor standards used for scheduling are particular for different operational reasons (union agreements, scheduling simplification, etc.). In these cases, management simply needs to be aware of the situation to avoid possible confusion on productivity measurement.

It is also important to note that if a PMTS is in place, a forecasting tool should also be in place. A very precise labor standard has limited value if the business forecast uses a rough estimate when scheduling. Since the quantification of workload is based on the multiplication of the business forecast with a labor standard, the result is at the lowest precision level of one of the multipliers. For example, if bagging items has a precise labor standard of 11.87 seconds but the forecast jumps by increments of five customers because it is manually determined (i.e., 90, 95, 100 customers), the workload is 1,068.3 seconds for 90 customers or 1,127.65 seconds for 95 customers. There is almost a full minute of workload between a forecast of 90 and a forecast of 95. The available precision in the labor standard is lost because of the lack of precision in the forecast.

This multiplication will provide the number of hours of work required during a selected precision time span. Although, as mentioned earlier, a schedule generally follows the same precision as that by which the business is measured, labor standards can rely on distribution patterns to allocate the calculated hourly volume differently within the time span and therefore result in a more precise time precision.

For the following steps, it is assumed that the business volume time span is equal to the resulting time span. For each activity, the business volume is multiplied with its related labor standard to produce the workload requirement:

Workload = Business Volume × Labor Standard

To determine the number of employees required during this time span, the time volume is divided by the time span:

Employees required = Workload/Time Span

Using our store example:

Forecast projects 100 customers between 7 p.m. and 8 p.m. on Thursday next week.

This translates into 150 minutes (100 customers × 1.5 minutes) of Process Payment and 20 minutes (100 customers × 0.2 minutes) of Bag Items for that time span

There is a requirement of 150 minutes of work within a 60-minute time span for the process payment activity.

The number of employees required, when dividing 150 minutes by 60 minutes, results in 2.5. When the scheduling process starts, a planner may elect to schedule two employees or three employees. But the fact that half of the employees cannot be scheduled forces rounding to occur. These rounding rules or guidelines have an important impact on the number of employees that will be scheduled:

- Combine activities. The organization section explains the combining of activities into jobs or functions. This allows scheduling to occur at a higher level and therefore reduce the impact of rounding. For example, if activities Process Payment and Bag Items are combined and scheduled at the higher activity Checkout Customers, the number of employees required becomes 2.83 (170 minutes [150 minutes + 20 minutes] divided by 60 minutes). This would result in scheduling three employees that can perform both activities.

- Round once only and at the last calculation. Rounding can occur at any step mentioned earlier. The labor standard could be expressed in minutes instead of seconds, which would therefore lead to a two-minute transaction in our example, and result in 200 minutes of workload instead of 150. Therefore, at each step, keeping a high level of precision as long as possible will reduce the impact of rounding. Since rounding the number of employees required during a time span is the most common approach, any other rounding performed earlier impacts workload accuracy. For example, if the labor standard is rounded to two minutes for Process Payment and to one minute for Bag Items, the workload for Checkout Customers becomes 300 minutes and therefore results in five employees instead of three.

- Don't round. Rounding is not mandatory. If planners know when the fractional part needs to occur, knowing the exact workload requirement leaves planners in control. In the example above, the 0.5 employee fraction could be scheduled at the end of someone's shift (shift ends at 7:30 p.m.) or at the beginning of someone else's shift (shift begins at 7:30 p.m.). A planner could also elect to have employees go on break during this time. Therefore, depending on the operational environment, workload can remain as a fractional expression.

iii. Task Management

Task management, from the workforce management perspective, represents the management and dispatch of task-driven activities (see “Task Driven” section). Task management includes task definition, quantification, recurrence, dispatch, tracking, and evaluation

Tasks can be more about a to-do list than about continuous repetitive work. For example, a bagger at a store has a base continuous activity of bagging items. The bagger also has a to-do of cleaning shopping carts every Monday. On Monday, the bagger will clean carts when there are no customers at the cash register. The task of cleaning carts does not need to be done at a specific time, but at any time in the day on Monday.

When deciding if an activity is a specific task or is part of the daily routine, a few key points can help:

- Quantification. How long does the task take? Usually, a task is broken down at a level where it can be completed within one hour. Longer tasks are difficult to fit within an existing schedule.

- Recurrence. Is the task required every day? A daily task may be simpler to add to the recurring workload where a weekly or monthly task needs to be specific since it is not part of a shift routine for the employee. Any activity that is tied to special nonrecurring events is in most cases a task. However, recurrence of an activity could create a significant volume of repetitive task work enough to shape a discreet role for workers with limited abilities.

- Dispatch. Is the task assigned to someone in particular within the pool of employees? If everyone within the same job needs to perform the activity, it may be easier to add the work to the recurring workload. In universal design a shared task could be dispatched to a single worker.

- Tracking. Is there a manager who needs to keep track of the completion level of these tasks? For example, security guards need to complete rounds and inspect the premises every hour. It is part of their daily routine, but someone wants to make sure the inspection round is completed.

- Evaluation. Is the employee feedback required on completion? Will a manager inspect the result for each task instance? If not, the task may not necessarily require specific identification.

Task management is often useful in large organizations where the head office may dispatch specific additional tasks to each site. Head office may want to keep track of progress on these specific tasks and evaluate the quality of the result. For example, a large retail chain has a promotional event for every store in a region. The region would send promotion material to each store and send tasks with instructions on how to get the store ready for the event.

An additional financial dimension is sometimes added to tasks. Workload can be constrained by a budget (see “Rules and Constraints”), so additional tasks may not fit within that constrained workload. In the previous example where head office sends new tasks to sites, these tasks would also include additional budget for each site. It is therefore important to keep tasks separated from the standard workload so that they can be easily identified.

The additional workload represented by tasks is important to the planner. This additional workload is usually distributed between peaks of recurring workload. A planner may also elect to create the schedule first on recurring workload only and then dispatch the tasks and adjust the schedule accordingly. This allows the planner to dispatch tasks when the workload is less than the employees present.

The planner may also elect not to dispatch the tasks when the schedule is created. If the task is short, it will be dispatched by the manager present at the time. The planner will only have to make sure there is enough staff to perform both the recurring workload and the additional tasks.

Task management systems are useful for identifying, tracking, and communicating tasks to managers and employees. When included in a WFM system, tasks can influence the shape of the workload. It is important to link recurring workload to task workload when a schedule is produced, but it is also important to keep them in a distinct view for easier daily scheduling decisions.

The major challenges around task management are mostly based on scope:

- Estimate. Is the time estimated for the task appropriate? Nonrecurring tasks are difficult to estimate and the schedule may not provide enough staff if the estimate is not sufficient.

- Level of detail. To which level of detail should tasks be tracked? An organization that is new to tasks should start at a high level and test the flow of communication and tracking first. Once the organization is comfortable, breaking down tasks to a finer level of detail usually encounters less resistance.

- Communication. How are tasks communicated? Task management has a big communication aspect. From the initial requester of the task to the employee performing the task (or part of it), information is key. In the previous example, the employees may have the instructions to set up the store for the promotional event but may not have received the posters. If employees don't know who to contact, the store may not be ready for the event.

- Tracking. How are tasks measured? How long did the tasks really take? Most organizations that start to track tasks require a status on each task and its actual cost. Actual time for a task will benefit the next time an estimate is required for tasks.

(c) Organization

Organizations need to structure responsibility, work, and information. When work becomes too much for one person, jobs are created and organized to stay productive and efficient. A structure grows and changes as a business evolves in time.

Organization structures are used for multiple purposes and depend on the perspective in play:

- Financial perspective. Accountants associate costs to certain categories or cost centers. They will organize these cost centers in a way that makes sense from an accounting and a management perspective at their appropriate level of detail. For example, a scheduler may need to know the section of a store where a cashier will work, but accounting doesn't need that level of detail.

- Management perspective. Human resources have an organizational chart detailing who reports to whom. This structure is important from an HR perspective and may be very different from the financial structure. For example, a new site opens in a country where a business did not operate before. If this site is an office with multiple activities (legal, HR, etc.), the head of each activity may report to someone different at the head office. Yet, from a cost center perspective, the new site is a whole different structure since employees are paid in a different currency. Thus, employees report into an existing department from an HR perspective, but employees from the same department may have different cost centers (one per country).

- Operational perspective. Operations have yet a different structure because it is mostly based on the required work at hand. For example, a new building is under construction and requires different skilled labor (e.g., electricians, plumbers). There is only one supervisor for the construction project and that person dispatches the work to the employees. Yet each employee, from an HR perspective, reports to a different supervisor (one supervisor for electricians, one for plumbers, etc.). The structure in this case is based on the work to be done and has a project perspective.

It is therefore essential to understand the business at hand before designing an organizational structure for scheduling purposes. In most cases, trying to design a single structure for all three perspectives leads to difficult situations where one structure exists, yet fails to answer each perspective's needs.

For the purpose of scheduling, the operational perspective is required. Workload breakdown needs to be organized in jobs, functions, sections, departments, and so on. An organization structure needs to reflect the operations of a business as much as possible.

Once activity breakdowns are complete, they are categorized within jobs. These jobs, functions, positions, and so forth usually represent the job titles employees are hired into. In the previous example, there would be two jobs: one job for a salesperson (Activity 1.1) and one job for a cashier (Activities 1.2.1 and 1.2.2).

Scheduling can occur at the activity level but in most cases will be done at an employee job level. The most common situation where scheduling would occur at the activity level is when employees are cross-trained and activities can be performed by multiple jobs. A schedule at the activity level allows employees to work on different activities depending on the workload required. A business would then be in a position to react to business volume changes by scheduling an already trained workforce in the areas where they are needed.

The workload should be organized in a way that reflects the operations at all times. The key indicators to consider when setting up an organization are:

- Location. Where is the work performed? The location of the employee indicates, in general, a point where the organization needs explicit levels. The locations can be sites, departments, stores, floors, and so on. Although the breakdown of the organization is essential to scheduling, it is important to keep the whole process flow in mind. The organization breakdown for scheduling practices also influences time captures and time approvals. Once the schedule is created and posted, it has to be worked and affirmed by frontline managers. The time approval process for these managers has to remain simple; having too much breakdown imposes a complicated process for them. For example, if a large store has two exits on each side, it may be wise to break down the organization cashiers into Exit 1 and Exit 2. This way, if different frontline managers are in charge of each exit, the process flow may be easier for them.

- Team. Which job requires another? If some jobs require other jobs in order to be performed appropriately, these jobs should be categorized together within the organization. For example, a bagger needs a cashier in order to bag items. Both these jobs should therefore be at the same level and within the same grouping.

The organization should reflect the organization of the work, not the workers. In any organization, workers may be qualified to work multiple jobs and may be scheduled in multiple areas. An organization based on employees and who they report to is exposed to frequent changes as organizations restructure and workload demand and location change regularly. However, the work often remains the same and the organization changes will occur if new sites open or process reengineering occurs.

10.2 RULES AND CONSTRAINTS

Most rules and constraints around the schedule creation and maintenance processes are either time-based or volume-based and apply to the workload, the workforce, or the organization. This section breaks down the different constraints a planner needs to deal with.

(a) Workload Constraints

When calculating workload, constraints coming from external factors influence the final shape and number:

- Presence constraint. Some activities are required even if there is no business volume. A minimum number of employees are therefore required during certain time spans. For example, a cashier requires a minimum of one resource during store opening hour; at least two first responders are needed per ambulance; and so forth.

- Resource constraint. Capacity issues need to be considered. If equipment is required to perform an activity, then a maximum number of employees can work simultaneously on that activity. For example, a store would have a constraint based on the number of cash registers; first responders are limited to the number of ambulances; and so forth.

- Budget constraint. Some industries like healthcare have strong financial and operational constraints. Even though a workload may indicate the need for six nurses, staffing requirements may dictate a minimum of seven nurses, and budget guidelines may suggest five. A budget constraint is not necessarily applied on the same precision as the volume demand. For example, stores have a budget constraint that applies on a weekly basis; the planner may have some flexibility on the actual times where the constraint is applied during the week.

Workload that has constraints sometimes gets lost in translation and becomes the workload per se. Organizations therefore have difficulty measuring the difference between the actual business need and the actual productivity.

For example, if business volume dictates that six cashiers are required but only four cash registers are available, the workload is constrained and turns out to be four cashiers. This ends up in reduced capacity for serving customers and although employees will be very productive, the service level to customers may suffer.

The same applies to the budget constraint example in healthcare: workload is six nurses (not five). Yet, the schedule is produced according to five nurses even though projected patient care requires six nurses.

Because the schedule is produced against the constrained workload, transparency to the real workload is often lost. The difference between the real demand and the constrained demand is a key indicator that the constraint requires analysis. This key indicator is calculated in the following way:

Demand ratio = (Real demand - Constrained demand)/Real demand

A demand ratio of zero indicates that the constrained demand is the same as the real demand. On the other end of the spectrum, a demand ratio of one indicates that the constraints remove all the demand. A ratio of 0.5 indicates that half the required staff will not be scheduled.

It is essential to express the difference in a ratio. A simple subtraction would not tell the whole story. In the healthcare example, the demand ratio would be 0.167 ([6 – 5]/6) because one nurse is constrained. The same unit but on another day may have a real demand of 10 nurses but be constrained to nine. The difference is still one nurse less, but the ratio is 0.1 instead of 0.167. The ratio indicates the impact of the constraint: the higher the ratio, the higher the impact.

(b) Workforce Constraints

Also commonly known as scheduling rules, workforce constraints are derived from the fatigue element of humans. Anyone who does work needs rest prior and after that work. There are a multitude of terms and definitions around rules or constraints but all of them represent the same concepts of work, work sequences, and rest.

Most workforce constraints are calculated against a measuring time span. This time span is simply a defined span of time against which hours or occurrences of events are compared. For example, an employee who has a maximum of 40 hours a week has a measuring time span of one week. This time span requires a specific weekday and start time to be precise. Constraints are established on different measures and the definition of these time spans is required to measure correctly. There should be no room left for interpretation. For example, if a week is determined to be from Sunday to Saturday, a shift starting at 10 p.m. on Saturday and ending at 6 a.m. on Sunday can belong to the week of the Saturday (shift belongs to the day it starts) or the Sunday (shift belongs to the day it ends). Even the criteria to determine where these hours should fall can get complex: shift belongs to the day where the majority of hours fall, shift hours are split between both weeks, and so on.

The measuring time span is therefore accompanied with a list of definitions that detail the rules required to count time correctly. These definitions ideally need to line up consistently. The defined end of a day should align with the defined end of the week so that the hours are counted in the proper day and week and that time allotment is in agreement. A day defined as starting at the start of third shift (11 p.m.) combined with a week that begins on Sunday at midnight would be considered an inconsistent definition of time.

i. Work Spans

In general, work starts when an employee begins work and ends when they stop working. The work span, or presence at work, or shift, is also broken down into smaller parts divided by breaks and/or job changes. Although most industries have their workforce go home after their daily shift, some industries have much more complex definitions of work span. For example, airline crew members can go on a multiday work span across the world before coming back home. This type of work span will carry different terminology and will also be broken down with rest time between blocks of flying hours. Although the crew stays overnight in a city, they are still within a work span dictated by rest rules within that span (see “Rest” section).

It is important to note that work hours are not necessarily equivalent to paid hours. The constraints on the work span are only a minimum and maximum duration from start (arriving at work) to end (leaving work for home). (Reference Chapters 6 and 7 for FLSA, and Wage and Hour rules around compensable time. Consider that schedules may need to include work time that is compensable such as prep or cleanup work, but not de minimus time.)

(A) Work Span Duration

The work span (shift) is constrained by a minimum duration so that an employee does not come in for work for only one hour, and a maximum duration to control total work span duration away from home, fatigue, cost, or productivity.

It is important to distinguish the duration of the work span and the amount of work. A work span of nine hours may result in eight hours of compensable work if a meal break is inserted in the middle of that span.

The exception to this rule relates to on-call or standby duty. When employees are on standby, they are usually home but they must remain available to come to work at a moment's notice. Although the employee is not at work per se, the employee is constrained, tied to the workplace, and usually compensated for this time. Standby may therefore be considered on the same level as any other job and be part of work span calculations and costs.

(B) Amount of Work

Constraints also apply to the amount of work hours within a measuring time span. The work hours represent the sum of what an organization defines as work. A nine-hour shift with a one-hour unpaid lunch would count as eight work hours. There may be two 15-minute paid breaks included in these work hours. Although this 30-minute total is paid but not worked, many organizations keep things simple and consider the paid breaks within the worked hours so that the work span is not impacted.

In order to illustrate the combination of work hours and measuring time span, here are a few common examples:

- Shift hours. Minimum and maximum work hours within a work span (work span is usually the same as the measuring time span).

- Daily hours. Minimum and maximum work hours within one day or 24-hour period (measuring time span of midnight to midnight, for example).

- Weekly hours. Minimum and maximum work hours within one week (measuring time span of midnight Sunday to midnight Saturday, for example).

- Pattern or rotation hours. When employees work a predetermined schedule that does not fit a standard week, the minimum and maximum hours are established within that horizon. For example, a 10-day pattern of work and rest days can have a maximum of 50 hours on 10 days. The measuring time span requires a time start, but also a fixed date that dictates when the 10-day pattern starts rolling.

These measured time spans often dictate how overtime is calculated. Overtime is generally established by work hours that go above the applied maximum hours on a measuring time span. Overtime can therefore be on shift hours, daily hours, weekly hours, or any other measuring time span that is applied by the organization.

(C) Work Span Occurrence

The occurrence of a work span can be counted within a measuring time span. One work span (shift) counts as one occurrence and the sum of these occurrences are compared to minimums and maximums within the measuring time span.

To illustrate the combination of occurrences and measuring time span, here are a few common examples:

- Shifts per day. Maximum number of work spans per day. Although most employees work one shift per day, a split shift would be considered two occurrences within the same day (measuring time span of 24 hours).

- Shifts per week. Minimum and maximum number of work spans per week.

- Days per week. Minimum and maximum number of work day occurrences within one week. In this example, note that the occurrence count is based on another measured time span (day). If an employee has two shifts on the same day, that day counts as one occurrence.

- Evening work. Minimum and/or maximum number of work spans overlapping an evening time span. For example, a work span overlapping an 8 p.m. to 1 a.m. span is considered an occurrence of evening work. A constraint can apply to a maximum of these occurrences in a measuring time span of a month, for example.

- Weekend work. Some industries need to distribute weekend work fairly across employees, either to maximize weekend work (because of higher pay) or to minimize weekend work (for better work-life balance). In both cases, weekend work needs to be measured according to precise definitions of what is the weekend time span and which work overlap counts toward a weekend. Some would count hours, others would count occurrences. In both cases, a weekend that is categorized as worked counts as an occurrence within a monthly time span, for example.

ii. Work Sequences

The work span constraints are about counting events or hours within a certain time span. Work sequence constraints are about the precedent and subsequent work events that constrain one another. Usually, work sequence constraints are represented by consecutive events of a similar type. For example, a maximum of two consecutive nightshifts would be considered a work sequence constraint.

In general, there is no time span related to sequence constraints and they are broken by events of other types like rest days. A few examples of work sequence constraints would be:

- Job or task sequence. When working a shift, certain jobs may be more difficult than others. These jobs may not be scheduled back-to-back in the same shift to avoid injuries.

- Shift sequence. Some shifts may be controlled in the way they can be sequenced one after the other. For example, an employee can only work two evening shifts in a row and must have worked at least a one-day shift prior.

- Consecutive work days. Minimum and maximum consecutive work days an employee can be assigned before a rest day.

iii. Rest

Unlike work hours, rest is rarely counted as an amount. Rest is measured with duration or a time span. The rest time span is not necessarily constant and may vary depending on preceding work constraints. For example, rest may be established to be 48 hours after four consecutive days of work but is extended to 72 hours after two consecutive night shifts. A few examples of rest constraints would be:

- Breaks. When working a shift, an employee will require breaks and meals depending on the shift duration.

- Minimum rest. The minimal duration between the end of a work span and the start of the next.

- Minimum number of consecutive rest days (or days off). If the employee does not work on a day, it is considered a rest day. A minimum number of consecutive rest days when one rest day occurs could be applied. Although this constraint is commonly expressed in days, it could also be expressed in a minimum rest span after a block of consecutive workdays. A minimum rest between two blocks of workdays could be set to 60 hours, which would guarantee a full two days off to an employee.

- Sleep shifts. (See Chapter 6.) Requirements around sleep and uninterrupted sleep exist in certain industries.

Like work spans, rest can also be counted against a measured time span. For example, instead of distributing weekend work, an organization could decide to measure and distribute equitably weekends at rest. From a scheduling perspective, a weekend work measure would in most cases be compared against a maximum whereas a weekend at rest would be compared against a minimum.

Rest is an active part of employee productivity and all time spans not worked. This includes vacation or paid time off. In most cases, employees take their entitled time off but minimums may be enforced on a yearly basis. (See Chapter 9, Section 9.1.)

(c) Coverage Constraints

Workforce constraints are the rules that apply to one single employee. When creating the schedule, the dimension in play is only that employee's timeline and the workforce constraints are all about one employee at a time.

On the other hand, coverage constraints, or organization constraints, are about multiple employees and putting together a schedule that makes sense from a moment perspective. For any moment within the schedule the coverage constraints apply.

Coverage is commonly referred to as the amount of employees scheduled and present versus the workload required at the same moment. If workload dictates three cashiers and only one is scheduled, there is under coverage of two cashiers. The same workload but with four cashiers scheduled generates over coverage of one cashier.

Thus, coverage constraints are generally caused by operational constraints and can be explained because of equipment restrictions, safety procedures, work processes, and so on. For example, in the previous workload constraints, a minimal workload of two first responders is applied because an ambulance must have two employees on board all the time. Although the workload says minimum of two, that constraint is also a coverage constraint where the schedule must have two people scheduled or else the ambulance does not operate.

The same applies to a manufacturing environment where three different jobs are required to operate a production line; if one of these jobs is not present, the line does not run.

The same concept applies to on-the-job training. When new employees arrive, they are matched with an instructor to go through training or orientation. Although two people are scheduled, only one is counted as productive at that moment. The new employee's status prevents counting toward workload (as if he or she were not there) yet the workforce constraints all apply.

The work within the organization may also dictate preparation time. If employees are required to wear special gear, they may need to be scheduled 10 or 15 minutes ahead of time to give them appropriate preparation time. The same applies for the end of a shift where a cashier would need some extra time to close the cash register.

10.3 WORKFORCE

From a scheduling perspective, the workforce represents the people that contribute to the workload. These people can be employees, external employees (temporary staff from external agencies), volunteers (a schedule is not reserved for paid staff), managers, and so on.

Regardless of their status, employees bring different skill sets and are scheduled according their potential contribution to the workload. But because each person's professional profile is different, scheduling does not commonly occur at that level of detail.

Employees are hired into jobs or positions where each position describes the requirements (person profile required) and the contribution or responsibility (what workload does it cover). Therefore, an employee who holds a position is considered competent to fulfill the expected outcomes of that position.

(a) Person Profile

Each person has a set of attributes that defines his or her abilities and his or her potential contribution:

- Qualifications and skills. The skill set a person has gathered through formal education, experience, on-the-job training, and so on. This includes recurring certifications, refresher trainings, and the like. Usually, people are in charge of their skill set and are responsible to keep them up to date. Some businesses will monitor key certifications to make sure that their employees keep the certifications they need for their position to keep the organization in compliance and provide quality service and product.

- Capacity. The capacity represents the number of work hours a person can contribute. This is usually expressed as a number of hours on a certain time span (see “Rules and Constraints” section). This capacity is not necessarily the same value as the constraint because it may represent a desirable value for the person. For example, a part-time employee would have a capacity of 24 hours a week, but a constraint of 40 hours a week to avoid overtime. This may also be referred to as standard hours representing the agreed on number of hours an employee is expected to work.

(b) Defining Positions

From a scheduling perspective, the most important factors to define are:

- Activities. A position/job needs to identify which workload activities will be covered when a person is scheduled to this position. Depending on the industry, a person may hold a position, be scheduled on a specific activity, and be dispatched to precise tasks on a day-to-day basis with all three levels using different terminology. Although this seems complex, most industries correlate activities to a job name and use that same job name to represent the position. This reduces some levels of abstraction and simplifies the scheduling process. For example, a workload activity would be expressed as Registered Nurse, therefore the person is scheduled as a registered nurse and the position the person is hired into is named registered nurse.

- Location. A position needs to be based at a certain location. For example, a registered nurse is usually located and hired for a department in a specific hospital. The location itself is not necessarily the lowest level; a nurse can hold a position that is based at the hospital. This would indicate that nurses are not dedicated to a certain department and that the position they hold is one that is designed to assign them to specific departments as needed when the schedule is created or the demand changes. Roles that are not tied to a specific department are sometimes called floaters.

- Work contribution. A position needs to establish the work contribution the person will provide. This contribution has multiple aspects:

- Hours. A position establishes the amount of hours to be contributed to a workload on a defined time span (e.g., 40 hours a week is expected as a full-time registered nurse in a certain department).

- Distribution of workload. One key detail that is often overlooked is the distribution of the workload, or how the hours are assigned among several workers. If a total of 160 hours of work are required in a week, one may quickly conclude that four full-time employees are required (160 hours/40 hours per week = four employees). But if that amount is not spread evenly across the week and the workload dictates that six employees are needed from 5 p.m. to 9 p.m. on Thursday evenings, that requirement breaks the four full-time employee model.

- Schedule. The contribution can also be expressed directly as a schedule (for example, 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday to Friday). It can be a mix of minimum and maximum hours combined with predetermined days on and off.

- Availability. A position may require minimal availability (in hours or specific time spans) from the person holding it. For example, a part-time position of 24 hours may request minimal availability of one day per weekend and a minimum of 50 hours of availability a week. Note that availability only indicates when someone is considered available for work, not the minimum number of hours they must work. Some organizations expect their employees to be available all the time. In these cases, the contribution indicates a maximum number of unavailable hours (if permitted).

- Effective dates. Some positions are created on a temporary basis and are therefore applicable only for a determined date span. At the end of the span, the position is terminated. This if most commonly used in seasonal businesses (e.g., ski resorts) or for replacements when absenteeism is high (e.g., to cover for summer vacations).

To determine the position mix a business unit requires, it is helpful to produce a fictitious schedule using blank rows or positions. Considering each row one or more persons, a planner can go through the scheduling process (see “Scheduling Process” section) and evaluate the quality of the resulting schedule. A planner can then modify each position's definition and determine the preferred mix for the business. - Determining and defining the right positions can be a challenge not only because of the business demand, but also based on other factors:

- Demographics. Demographics have a major influence on the position definition. For example, the pool of employees available to a business near a college campus is mostly students wanting to work part time. If the business only posts full-time positions, there may be a challenge in filling these jobs. Therefore, the business may change from four full-time positions to eight part-time positions.

- Predictability. Positions can express their contribution in many different ways (hours, days on-off, specific schedules, etc.). When deciding how to express the position's contribution, the key factor to examine is the workload predictability. If the established workload is fairly regular and rarely changes from week to week for example, then a position could go as far as specifying the exact schedule. But if the workload changes from week to week, then it may be better to simply indicate a number of hours over a defined time span (see “Scheduling Process” section).

(c) Position Types

Although position definitions may vary, the most common ones are related to the number of hours within a position:

- Full time. Usually represents a position with a contribution that is the equivalent of the maximum number of hours defined in the scheduling constraints. The number of hours expressed within this type of position is also used as a measuring base commonly called a full-time equivalent (FTE).

- Part time. Usually represents a fraction of one FTE. For example, 0.5 FTE would translate to 20 hours a week if one FTE is described as 40 hours a week. Note that the FTE measure is also used as an indicator for eligibility to benefits within the organization. Although the eligibility does not influence the scheduling process per se, planners may use this measure to minimize, balance, or maximize the FTE value attributed to employees.

- Seasonal. A seasonal position refers to employees working only during a certain portion of a year, but on a regular yearly basis. For example, a ski resort operates every winter and therefore has seasonal positions usually held by the same persons. Seasonal positions can be full time or part time as well; the seasonal aspect does not influence the recurring contribution during the season.

- Temporary. A temporary position refers to employees hired for a specific period of time (full time or part time) that is not recurrent. This is usually to respond to very specific events or situations like maternity leave, special ad campaign that increases business volume, and so on.

- Agency. Agency positions are commonly used as a last resort. Contacting an agency to fill a position is mostly for urgent and short-term needs. This is to cover for unexpected absences, unexpected increase in demand, and so on. Sometimes, agency use may reflect the need to open new positions on a permanent basis. It may also be due to very rapid business growth where filling positions does not happen fast enough to fulfill the demand or due to high turnover rates where people leave and the positions constantly remain open. There are many factors that influence agency use and any related measure or indicator should be carefully analyzed to determine the exact cause of this use. On a final note, agency use is not necessarily to be avoided at all costs; it must be examined within the operational context of the business and the various costs involved versus opening new positions and hiring more people.

10.4 SCHEDULING PROCESS

Scheduling is a recurring process that assigns blocks of work to persons while respecting defined constraints and covering business demand.

This section explains how to move from workload to a final schedule and identifies key decisions that have a major influence on the process.

(a) Workload Breakdown

In a demand-driven context, the first step in the scheduling process is to break down the workload into work spans (shifts). Depending on the industry, this step is either essential or not required altogether. For example, most manufacturing businesses mostly have predetermined shifts of 8- or 12- hour durations with fixed start times. In this industry, the workload breakdown is not required because the workload precision is at a shift level already and that resolution is the same as the shift start and end times.

But businesses like retail carve their shifts up to a 15-minute precision level with varying start times and durations.

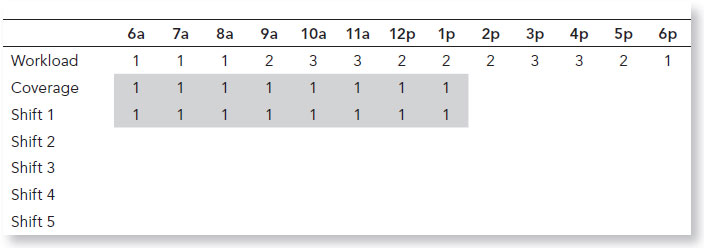

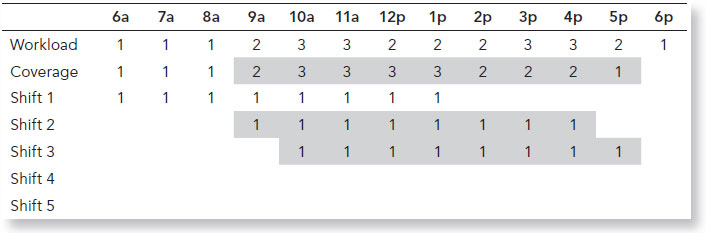

The example illustrates different decisions and the impact on coverage (each column represents a unit of precision—one hour in this case—and each row represents a potential shift). The workload is expressed in number of employees required represented in the “coverage” row.

Decide on shift duration. The first step is to pencil in fixed shift durations starting at the earliest time. For this example, eight-hour shifts are penciled in (from 6a to p).

Continue with next start times. Continue to pencil in more shifts of the same duration but starting at points where coverage is required. In this example, this would mean 9 a.m. and again at 10 a.m.

Complete with short shifts. The previous step called for a shift at 3 p.m. but the workload stops at 7 p.m. Therefore a four-hour shift is penciled in.

In the example, the resulting coverage is fine except for the noon to 2 p.m. period where one extra person is scheduled. In light of this information, a planner may take the following steps:

Key point: The total hours of the workload in the previous example is 26 hours. It is essential to note that four shifts of different start times and durations are required to cover a demand of 26 hours for one day. If only looking at the total number of hours, one may conclude that three shifts of nine hours would be sufficient to cover that day but may produce unwanted coverage. This shows that trying to determine a number of positions required using only totals may lead to wrong conclusions.

In a real context, workload can produce up to 20 or more shifts per day and can cover 24-hour periods, seven days a week. Here are a few tips on how to break down workload manually:

- Identify the lowest and longest span of workload. This is usually during the night. It might also be a weekend. It is recommended that night shifts be minimized and determined first since they are most commonly disliked by employees and are known to disrupt sleep patterns and cause additional fatigue.

- Identify the real peaks. Workload variance can go from a demand of 10 persons to a demand of 15 the next hour and back down to a demand of 10 the next hour. These types of peaks can disrupt a schedule especially if the precision level is very low (15 minutes). To identify the real peaks, a demand must be steady for a meaningful duration (i.e., relative to the shift durations). The demand increase must also be meaningful. For example, a demand of 20 employees increasing to 21 employees has much less impact than a demand of two employees increasing to three employees. Once the peaks are identified, shifts start times are penciled in at the beginning of the peak and other shift end times are penciled in at the end of the peak. This way, multiple shifts overlap their start and end times to cover the peak and reduce the total number of shifts.

- Merge shifts. Once all shifts are penciled in, a planner may elect to merge short shifts into longer shifts to reduce the total number of required shifts for the day. This decision usually depends on the pool of employees available. For example, if the pool of employees is mostly part-time workers with low individual availability, a planner would keep the shifts short. On the other hand, if there is a shortage of employees, a planner would merge shifts to reduce the shift count.

(b) Context Decisions

There are many different approaches to work assignment that can be categorized into three contexts:

Cyclical Schedule

Businesses can apply a mix of the three contexts within the same schedule by having a rotational schedule for the basic recurrent demand and a nonrecurrent additional schedule for the varying demand.

Key decisions on the scheduling process usually happen at this stage. The workload profile is analyzed, a sample of shifts is available on a daily basis, and the base and/or recurrence of the workload is known. The decisions required before moving to the next steps are:

- Recurrent positions. If shifts are always the same start-end times, the selection of either cyclical or rotational schedules is probably the leading practice. If cyclical and/or rotational schedules are selected, they need to apply to the recurring shifts that are constant over the year. If the number of shifts varies over the year, then the cyclical/rotational schedules are built around the lowest point of the year. The other positions would contain only a contribution of hours with no predetermined schedule.

- Schedule time span. A schedule requires a certain time to create and maintain. A planner can create a schedule for one week, two weeks, four weeks, one month, and so on. The selection of this time span is determined by the expected variation of the workload and the expected variation in employees. The higher the variation in either, the shorter the schedule time span should be. For example, if all employees have been in the department for many years and all these employees are on a rotational schedule, then the schedule time span can be very long because changes would most likely occur for absences and vacations. On the other hand, if employees are students who change availability or jobs regularly, then the schedule time span should be one week or less.

- Posting notice. The posting notice is the minimal amount of time required between the moment the schedule is posted to employees and the moment the schedule starts. For example, a schedule starting Sunday morning at 6 a.m. posted on the previous Thursday at 6 p.m. gives a posting notice of 60 hours. The posting notice is important for employees especially in a nonrecurrent context. In this example, employees can't plan for the weekend until Thursday evening because they will not know if they are working Sunday or not until the schedule is posted. For a business, the probability of a schedule change is higher the farther out the schedule is posted.

- Employee input deadline. In certain businesses, employees can inform the planner of their availability or their preferred shifts for the upcoming schedule. Because a planner requires a minimum amount of time between the employees' input and the posting notice, the deadline has to be established from the planner perspective. How long does it take to gather the input? How long does it take to assign the work? How similar is the schedule from week to week? How many employees is the planner scheduling? The answers to these questions and more determine the amount of time required to create the schedule and therefore establish the deadline for a planner to start working.

(c) Employee Input

In the scheduling process, employees commonly have the opportunity to provide information about personal constraints and preferences that would influence the planner's decisions.

i. Absences

Planned absences (i.e., vacation for most cases) usually follow a parallel process that allows the employees to request an absence. Absences are planned longer in advance and are therefore already set when the planner gets to create the schedule.

The usual way to plan absences is to compare against a certain capacity. Since the actual workload and the detailed schedule are not known at the time of approving absences, a planner has to rely on a capacity measure rather than a coverage measure.

The most common and easiest way to control absence approvals is through quotas. For each week (or day) of the year, a department dictates the maximum number of employees that can be absent on the same day. This quota is usually shared with employees so they know when there are still available days for them to request.

Quotas are not necessarily equivalent throughout the year. The quota can change relatively to the workload so that when business demand is highest, paid time off (PTO) approval is lowest.

The absence approval process can also vary by absence type. For example, requests for vacation can follow a yearly selection process with a weekly quota whereas requests for personal time off can follow a weekly process with a daily quota (both quotas being distinct or merged).

The important point to remember is that absences take away from a planner's capacity to assign work. It is therefore important to approve and/or refuse absence requests prior to assigning work.

ii. Availability

Employee availability can take different forms in terminology but normally represents the same concept: the time frame the employee is available to work or not.

Depending on the business context, employees can be considered unavailable all the time and it is the employees' responsibility to provide their availability if they are to be scheduled. However, other business contexts consider the employees available all the time and it is still the employees' responsibility to provide their unavailability to avoid unwanted work hours.

In both cases, measures are sometimes put in place so that there is some fairness in the distribution of unwanted work hours. For example, if employees dislike night shifts, they may have to provide availability for a minimum of one night shift per week.

Each department probably has different measures and different terminology for employees to express availability:

- By shift name. The shift terminology of a department is usually what is used to communicate (D for day shift, E for evening shift, etc.). Employees therefore know what general time span a shift represents even though the actual start and end times may vary. Employees therefore express availability through the shift name.

- By shift duration. Some businesses allow employees to mention availability using shift durations. For example, an employee may elect to be available only for shifts that are six hours or longer (or vice versa).

- By weekday. Employees can mention which weekday they are available to work. This is mostly used in contexts where employees are signed up for formal education.

- By department. Employees can mention which department or location they want to work in. Even though they would be qualified to work different locations, they express the fact that they are only available for a subset.

- By job. Employees can mention which job they want to work. Even though they would be qualified to work different jobs, they express the fact that they are only available for a specific job.

- By pay. Employees can mention that they are available for work only if it pays overtime. This type is mostly used in contexts where the employees have positions with cyclical or rotational schedules.

Employees in some contexts are allowed to be precise on availability and combine one or more of these factors. For example, employees may sign up to say they are available for the evening shift on Monday for the cashier job only if it pays overtime.

It is important to understand that information provided under the availability terminology means that it is considered factual information that is applied to the schedule. For example, if an employee is available for a day shift, that employee will not be scheduled for an evening shift.

The amount of latitude given to employees has an influence on the perspective of the schedule result. The more employees have an opportunity to express detailed availability, the less capacity the planner has to complete the schedule. The mix of availability details allowed for employees requires careful analysis within each operational context.

iii. Preferences

Employees can express preferences in exactly the same way as they would express availability. The difference between availability and preferences is the interpretation given to the information. A preference represents a wish or something the employee prefers. A preference does not prevent a work assignment that does not match that preference.

For example, if an employee prefers day shifts, that employee may still be scheduled for an evening shift.

In some industries, preferences are expressed in a multitude of ways and some are ranked or weighted in order to determine which preference is more important than another. Usually, these industries use high-end software to maximize these preferences and create the schedule optimally and automatically.

iv. Self-Scheduling

Some industries operate with a method called self-scheduling (most often used in healthcare). This method revolves around the fact that employees will select their own shifts to work and pick from an available workload. In this method, the employees view the required workload and sign up for shifts when workload is required.

The first employee to sign up has an open field of choices whereas the last employee will only be able to pick shifts that cover the remaining workload.

The selection process is managed by rules that the business needs to establish. If employees need to share unwanted shifts, then rules governing self-scheduling would include a minimum number of night shifts, weekend shifts, and so on. The self-scheduling process does not have to be complete. Organizations may elect to establish a process where only the unwanted shifts are picked up through self-scheduling. The remainder of the schedule is completed by the planner.

(d) Work Assignment

A planner can assign work to either positions and/or employees; both follow the same process. A schedule prepared with positions is usually done to determine the number of positions required and the contribution of each. In this case, the planner starts with a first set of positions and iterates within the work assignment process until a schedule is satisfactory.

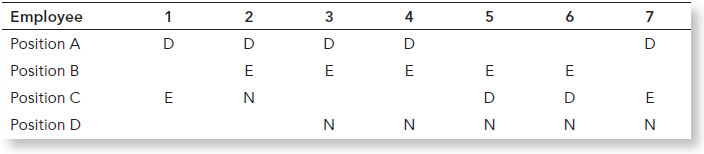

A schedule prepared with employees has more preparation time as the planner needs to organize the input that came from employees. That input needs to be written in the schedule in a form that is readable to the planner. An example is not provided intentionally because each industry and each department has valid terminology and annotations that are different from one another. This section concentrates on the process of attributing shifts to employees only considering availability on a daily precision.

When assigning shifts to employees, the planner needs to look at two key elements for each day of the schedule:

These measures are explained previously as being per day, but they can be at the required precision. For example, the measures could be per shift and would therefore show capacity versus requirement on a per shift basis. In this case, a planner would probably elect to schedule the most unwanted shift (generally the night shift).

These two measures are focused on the vertical constraints of the schedule. The planner must also be aware of horizontal constraints that impact employee capacity. For example, when employees get to their maximum number of hours, the days that no shifts are assigned become unavailable and impact the vertical capacity measure.

Although there are two dimensions to keep an eye on, the vertical constraint is usually the starting point for a schedule. The general idea is to assign the shifts that only have one potential position or employee. For example, if there is a requirement for one night shift on Tuesday evening and only one person is qualified and available for that shift, it should be assigned first. One shift to one employee is an easy example, but a day with three shifts and three employees available would also be a day to start the schedule with.

The next step is to analyze the difference between the number of shifts required per day and the capacity for that same day. The focus should be on the days that have equal or lower capacity than the required number of shifts. A planner can consider the days with capacity higher than the required shifts as the days that are used to adjust the schedule horizontally. When the capacity is higher than the number of shifts on most remaining days, then planners can tip their focus and look at the schedule more horizontally than vertically. It is also good practice to schedule adjacent days and not skip days in between.

It is important to note that these are guidelines only. Each operational context requires a different analysis. For example, horizontal constraints can dictate the next move for a planner regardless of coverage. If a constraint says that after an evening shift, there is a mandatory night shift the following day, then the planner should start by scheduling evening shifts first so that night shifts are scheduled promptly after (or vice versa where the night shifts are scheduled and the evening shifts are placed on the previous day).

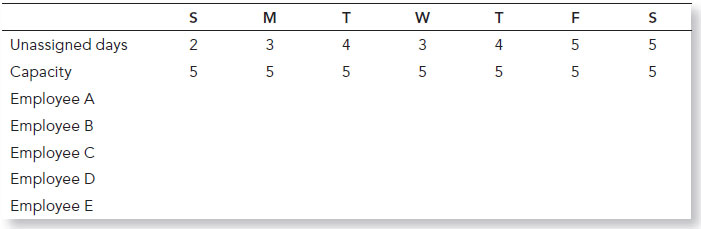

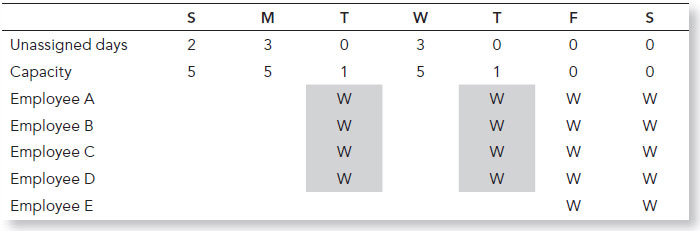

To illustrate the steps, the following example shows a simple schedule that requires the assignment of days on (W) and days off (O). The only constraint is a maximum number of five days of work within the week.

Step 1: Identify the days where capacity is equal to or lower than the workload (Friday and Saturday) and pencil in everyone for these days:

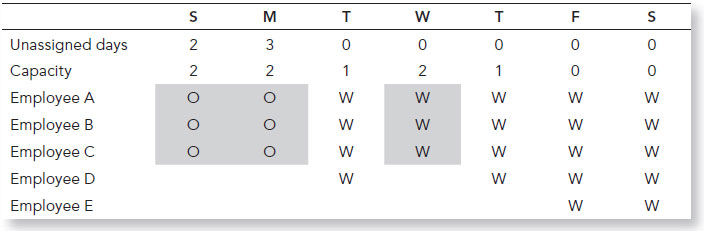

Step 2: Tuesday and Thursday are the next highest days:

Step 3: Wednesday is the next day and also completes the first three employees with days off:

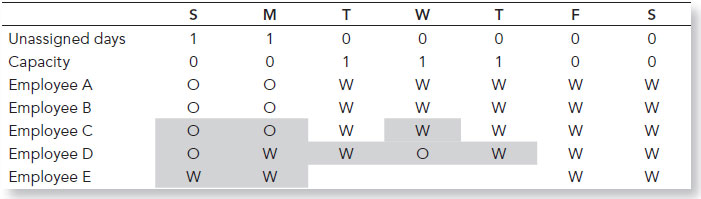

Step 4: Complete the schedule by assigning Sunday and Monday. Notice that the final result leaves two unassigned days and leaves Employee E with the capacity to be scheduled on one more day. This is usually an indicator that some movement of assignment should occur and that a horizontal constraint was not examined at the proper time.

Step 5: Stepping back, the planner should have completed the first three employees' schedule and kept scheduling the adjacent days from a horizontal perspective instead of skipping over Wednesday.

Step 6: With this approach, the planner can now see that Sunday and Monday should be completed prior to Tuesday and complete the schedule of Employee D.

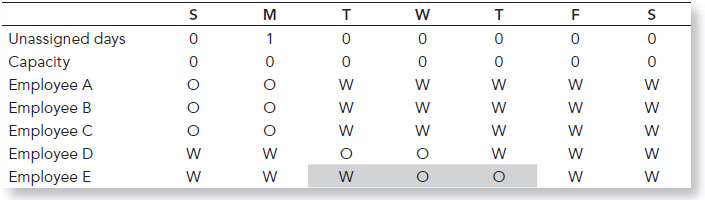

Step 7: The Tuesday shift can now be assigned to Employee E and have a full schedule for each employee and only one unassigned shift on Monday (versus two unassigned shifts in step 4 above).

Although this example is for a small group of workers, it shows how easy it is to create a schedule that generates overtime. In the above examples, any unassigned shift that is later assigned and exceeds 5 per employee per week becomes an overtime shift. In step 4 there would have been two overtime shifts but by step 7 the problem was corrected and there was only 1, which is expected. There were 26 shifts and 5 people who can work 5 shifts each (a total of 25 shifts). The 26th shift for this group will be an overtime shift. Step 4 shows how costs can rise if the details and mechanics of building a schedule are misunderstood or neglected.

There are many ways to create a schedule but all are based on the same principles seen above. Each industry applies these principles differently in order to support their operations.

The critical element for planners is to be aware of how the business operates and adapt their scheduling process to these operations.

(e) Schedule Maintenance

Once work assignment is complete, a schedule is posted to the employees. As soon as that posting occurs, the planner generally has much less flexibility on the changes that can occur. Posting, to a certain extent, represents a commitment from the organization to the employees that this is when they will work. In return, the employees show up at the posted times.

An organization needs to choose the level of detail to post. The minimal information employees require is the start and end times of their shift. Even if a planner has scheduled all breaks and the precise locations and jobs, it is not necessarily recommended to post the complete information. The more information that is posted, the less flexibility a planner has to make changes after posting.

Changes still occur after posting but are mostly due to external events:

- Change in business volume. Depending on the industries, planners can send people home early or extend their shifts to accommodate varying business volumes. Other businesses are committed to the schedule that is posted even if business volume drops dramatically.

- Unplanned absence. A planner usually needs to react when someone does not come in for work. The planner that needs a replacement would first go to the standby employees (if there are any), then examine the part-time employees who still have regular hours, then move on to overtime.

- External factors. Weather, emergencies, equipment breakdowns, and so on are all uncontrollable factors that generate a change in a schedule. Again, the changes depend on the business and its operations.

As a last step before a shift actually starts, a planner, or a supervisor, has to dispatch the employees to specific places or jobs. For example, a cashier in a grocery store is expected to start at a certain time but needs to be dispatched to a specific lane number. That last decision was not identified in the schedule.