CHAPTER EIGHT

Compliance, Controls, Reporting, and Payroll Leakage

IN THIS CHAPTER, THE LEGAL and financial concerns surrounding or involving timekeeping and workforce management (WFM) systems are addressed. In many cases, an intelligent WFM system is the solution to effectively managing compliance, regulation, or other labor laws. It is also the primary conduit of an exchange of labor activity and cost information across the organization and a potential source of serious cost from fraud, abuse, and neglect.

Consistency should be an essential principle to many more of an organization's efforts and initiatives than simply those involving laws or legalities. A WFM system, along with appropriate Workforce Asset Management (WAM) tools and leaders, delivers such consistency. If issues do arise, then the WFM system is much easier to navigate and produces more meaningful results than paper-based records or systems. This chapter offers leading practices on data and system management and security, including tips on creating a legally defensible and easily auditable system, designing roles and accounting structures to facilitate monitoring and enforcement, safekeeping the proper records and data, and mitigating fraud, misuse, and leakage.

- List the general steps an organization should take when designing a legally defensible timekeeping system.

- Understand the different types of user roles and how they relate to or interact with WAM system processes, policies, or procedures.

- Identify places of higher vulnerability within the system and develop methods and plans to mitigate potential issues.

- Recognize key elements involved in configuring editing and creation capabilities, privacy settings, and password requirements.

- Understand how statistical examinations and valid timekeeping data play a role in the cases surrounding the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) and state wage and hour laws.

- Know which WFM technology tools support the audit process and how they are effectively used.

- Identify leading practices for creating the structure for accounting codes (relating to the chart of accounts) inside WFM systems: labor levels and organizational hierarchy and explain situations to consider when creating this structure.

- Understand vulnerabilities within WFM system practices and design and how to prevent the most common types of WFM system fraud, abuse, and leakage.

8.1 DESIGNING LEGALLY DEFENSIBLE SYSTEMS AND POLICIES11

Timekeeping and time-reporting policies and practices must be designed to correctly capture time worked by nonexempt employees and to help protect the employer against employees' potential wage and hour claims. The number of FLSA claims have been staggering in the past few years. In 2010 and 2011, lawsuits filed for FLSA claims hovered well above 6,000 per year.1

Many of the wage and hour claims against employers center on allegations that the employee worked time that was not captured by the timekeeping (and payroll) systems (i.e., work performed off the clock). In advancing such claims under the FLSA, an employee carries the burden of proving:

- Hours worked were not credited (or paid).

- Employer “suffered or permitted” the work to be done on its behalf (i.e., that the employer knew or had reason to know that such work was taking place).

- Uncompensated work constituted overtime (i.e., work in excess of 40 hours in the week it was performed) or that this work, when combined with the compensated work, brought the employee's average hourly wage below the federal minimum wage.

In off-the-clock cases, the employer's principal substantive defense is to show that the employee's claims of uncompensated work are not credible. To properly prepare for such a defense, the employer should maintain sophisticated and user-friendly policies and practices that make it unlikely (and unbelievable) that an employee would have engaged in off-the-clock work that was known to the employer. The employer should also maintain a timekeeping system that generates records that help to contradict employee claims. These matters are addressed in turn in the following sections.

(a) Leading Policies and Practices that Protect Employers

When it comes to policies and practices, employers should strive to be proactive. The cost for being unprepared, neglectful, or inconsistent—whether at the corporate level or individual manager level—can be steep. Employers should focus on (1) developing strong policies, (2) conducting frequent training, (3) monitoring compliance with their policies, and (4) enforcing policies, as detailed next.

Clear Written Policy Should State the Following:

- All work time must be reported.

- Employees must be paid for all time worked—no work can go unreported.

- Provide in written materials examples of work activities that constitute compensable time that may not be obvious (e.g., handling e-mails/texts off hours on handheld devices, business phone calls off hours, interrupted meal breaks).

- Managers/supervisors may not require employees to work unrecorded time.

- Managers/supervisors may not modify employee time entries without documentation signed by the employee whose time is being modified.

- Any concerns about pay or reported time should be raised promptly so that prompt correction can be taken.

- Time systems (described later) should contain affirmations by the reporting employee about the accuracy and completeness of the time records and an acknowledgment of the employee's understanding that any concern must be promptly reported.

Conducting Training

- Take appropriate steps to disseminate policies, including during initial employee orientation. This can include access to key policies within the timekeeping system at time of login or in the text of reports and forms.

- Obtain (and keep) written acknowledgment of receipt and understanding of policies (mere posting or inclusion in employee manual is not enough).

- Provide frequent refresher training for employees and managers alike—require and retain training class sign-in sheets (or electronic equivalents for computer-based training).

- Determine employee understanding of policies (e.g., with quizzes at the end of each topic reviewed via online training) and retain related records.

- Sensitize supervisors to tricky wage and hour issues such as interrupted lunches, work completed before/after shifts, employees taking work home to catch up, and train supervisors on zero tolerance for off-the-clock work.

- Train managers/supervisors on how to spot irregularities in time records and to report/fix them promptly—consistently document the training message and its delivery.

Continual Monitoring

- Inspect timekeeping system to identify irregularities. For example, inspections should look for changes to employees' time stamps (e.g., entry time or exit time, meal break times) that are undocumented; signs that employees are gaming the system by returning early from meal breaks; lack of employee approval of their time records; failure of supervisor to review and accredit employee time records; time entries that appear rounded (instead of reports of time to the exact minute); complete absence of overtime during busy periods, and so on.

- Provide easy—and well-publicized—ways to report any concerns or policy violations (even anonymously) (e.g., an ethics hotline). The steps to access these reporting mechanisms can be displayed prominently via the timekeeping system.

Consistent Enforcement

- Follow up on identified/reported violations or irregularities.

- HR or payroll personnel should question employee about accuracy of report.

- HR or management should question supervisor about suspected irregularities.

- Maintain records of investigations.

- Prepare action plan for correcting identified problems.

- Reminders from management (e.g., cascading e-mails from senior executives).

- If the problem is severe/widespread, organize supplemental training programs (and maintain records of such training).

Discipline Violators

- Employees who do not follow policies should be disciplined, up to and including termination.

- It is unhelpful to be portrayed as soft on wage and hour violators.

- Maintain records of discipline for wage hour violations.

- Prepare communications from senior managers about the discipline imposed on violators (without identifying them).

- Make sure that back pay is provided to impacted employees.

(b) Key Features of Timekeeping Systems That Protect Employers

The FLSA and applicable regulations do not mandate the use of any particular type of timekeeping system, so long as the system correctly captures employees' time worked. Lawful systems range from paper timesheets to traditional time clocks to minute-by-minute computerized timestamps entered by employees.

i. Record Keeping

Effective timekeeping systems keep positive time (i.e., time affirmatively entered by the employee), with exact start time (e.g., 8:34 a.m.), exact time for start and end of meal break, and exact stop time. Conversely, timekeeping systems (or time sheets) should not contain preset information based on employees' scheduled shifts and/or anticipated meal breaks.

Also, timekeeping system should avoid auto-deduct features for meal breaks. If auto-deduct is in place, then inspect the system regularly, propose and memorialize frequent training, and make it easy for employees to submit exception reports.

To safeguard against any unaccounted time, the system should provide a well-publicized and convenient way for employees to report any time worked while employees are away from the timekeeping systems (e.g., work at home).

Timekeeping systems should record—and prevent deletion—of any modification to employee time by a supervisor or manager. In other words, it is an acceptable practice to allow supervisors to make edits to employee time entries, but the edits must remain documented in the system to allow easy inspection of any action taken. Each request for modifications to time records should also be documented, and the documentation should be maintained. Employers that diligently inspect the modifications to employee time records—and discipline violators—will have stronger arguments against employee claims of time shaving (i.e., supervise modification to employee time records to reduce credited hours).

ii. Verification and Payment

The system should require employees to affirm their time records each week. However, this does not imply that payment should be withheld from employees who fail to do so. The verification process should include a signed affirmation by the employee that the time records are correct and reflect all time worked (including time worked away from the principal place of business).

System checks should identify employees who fail to affirm their time and supervisors who fail to regularly approve time records. Violators should be disciplined.

In addition, the system should provide an easy way to report any concerns they notice in the review of their time records, including ways to report without going to the immediate supervisor.

iii. Recording Meal Breaks

Systems should incorporate any break requirements set forth under state law. In addition, these systems should automatically treat as compensable any break of less than 30 minutes. Thus, if an employee clocks out for a meal break and clocks back in before 30 minutes have elapsed, the employee should be paid in full for what may be a short meal break or an interrupted break.

Employees should be advised to clock back in for work performed during a scheduled meal break. Thus if the employee goes out on break, clocks back in after 10 minutes for a 5-minute period, then clocks back out for another 15 minutes, the system will show no break of 30 minutes or more, and the interrupted meal break will be paid in full. Managers should be instructed that they are not permitted to modify short meal break time entries without written authorization from the employee.

However, employees should also be advised not to clock back in early unless required to do so for work. The employer should evaluate to determine that employees do not game the system by purposefully clocking in a minute or two early and thus getting paid for a meal break when they in fact were provided a break and were not required to interrupt it early. To reduce gaming, some organizations have considered restricting a return punch so that the employee cannot clock back in before 30 minutes. If the employee did have an exception, then he or she could file an exception form with the supervisor, who would later edit the punch. However, this idea is discouraged because it places the burden on the employee to take an additional step (i.e., filling out an exception form) to be paid correctly. Some employees may claim that they were discouraged from completing exception forms, even when it would have been appropriate to do so.

In California, the payroll system should generate a payment of one additional hour of pay for any day in which the employee did not record a 30-plus minute meal break within the time frames required by the Labor Code (the untaken meal break [UMB] penalty). Other such prominent requirements in California law include meal break waiver forms, untaken rest break penalty, timing and number of meal and rest breaks, and so on.

Note: Wage and hour rules are subject to change and the requirements identified here should be confirmed at periodic intervals.

iv. Rounding

Another automated process a timekeeping system should review and monitor is the rounding of employee time. If the system rounds time, make sure that the system rounds forward and backward so that the rounding does not consistently favor the employer. Be sure to notify employees of the rounding rules and policies, and maintain records of subsequent communications, policy statements, or additional training. Regularly inspect the system and analyze the data to confirm that the rounding appears neutral (i.e., sometimes it rounds up, sometimes it rounds down, and the rounding largely cancels itself out). Any discovery of inconsistent or unfair practice should be modified promptly.

v. Policy Publicity and Ethics Hotline

In the case of any employee confusion or concern related to wage and hour, it is helpful to provide statements of policy and the toll-free number of an ethics hotline. In an electronic timekeeping system, this might be found on the opening screen or homepage. In a paper timesheet system, the timesheet itself can contain the same preprinted information, for example, right above the place for the employee's signature. Periodically, the system should remind employees about existing policies and obligations, as well as the available mechanisms for reporting concerns.

Where possible, the system itself should incorporate the requirements set forth under state law. A state-by-state survey of such requirements is beyond the scope of this article, but the most prominent requirements exist under California law.

(c) A Look toward the Future

The modern workforce and upgraded technology (such as cell phones, smart phones, and tablets with e-mail capabilities) are blurring the lines between work time and personal time. Employers, employees, and lawmakers must evolve and adapt to these new challenges. Employers can reduce their risk by following the guidance of this section: document clear policies, design and conduct effective training—especially with managers and supervisors—repeatedly communicate a zero tolerance message (all time must be reported), monitor and inspect regularly, and punish when necessary. Employees can reach out to company ethics services, or the Wage and Hour Division within the Department of Labor. To design a legally defensible WFM system, the whole workforce should accept, participate in, and contribute to its mission. From the CEO who disseminates goals and objectives of the WFM system and monitors its implementation, to the manager or supervisor who enforces the policies, to the employee who follows policy guidelines and alerts higher management to any irregularities or illegalities, WFM involves everyone.

8.2 MANAGING ROLES WITHIN WORKFORCE MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS12

Two elements of successfully implementing and utilizing workforce management systems are an organization-wide effort to delegate responsibilities and a communication program related to user expectations. Responsibilities must be delegated and assigned via the proper system access to allow individuals to perform their duties. Each employee should have clear instructions on his or her role in the system.

During the initial design phase of a WFM system and subsequent upgrades and modifications, an assessment of user roles and system functionality should be performed. Consider performing periodic assessments of the set up of user access to make certain that new functionalities during an upgrade or modification are handled with the proper user controls. Create a detailed list of the system functions that will be turned on. Map each feature and functionality to the user or user group that will need access to the component. Describe each user group and understand how they will be identified (e.g., by job or department or name). Gain consensus on who will approve the user groups and security access assignments and how and where security access mapping will be documented, communicated, and stored.

Employees and managers should be trained on all features that are available to them in the system. In addition, it is imperative the instruction goes beyond system functionality. An organization should communicate, at many levels, the expectations around employee conduct, responsibility, and accountability. Everyone needs to understand the desired outcomes related to productivity, cost, and quality.

(a) Worker Population

The primary timekeeping functions for the general employee population include the proper method of clocking in/out, as well as any necessary job costing and location, task, or project tracking. To further maximize workforce productivity, employees should be fully competent in using self-service functions, which may include benefit accrual look-up, time off requests, viewing work history, schedule requests or look-up, and notifying a manager of missed punches, canceled meals, or other important work-related notifications.

Employees must thoroughly understand their role in compliance and repercussions for any misconduct. Timecard fraud may be serious enough to be grounds for dismissal. Examples of noncompliant behaviors include punching in for another employee, changing an employee's timecard data without authorization, reporting time that was not worked, working unapproved overtime, or failing to sign off on timecards in a timely manner.

(b) Management (Managers/Supervisors)

Management's role is both tactical and strategic. Workforce management systems automate the reporting and review of reported time as well as facilitate better planning and management of labor utilization. Managers execute the organization's decisions and plans for how it responds to labor supply and demand. The tactics employed manifest themselves in the user roles that proscribe what features and places the user can access to get the job done. These tactical assignments should be aligned with organizational success enabling the employer to achieve its objectives (selling, producing, servicing, delivering care, etc.) with the right person at the right place at the right time and for the right cost.

The strategic role of managers is not only focused on the business but also on its people. Organizations are increasingly learning that managerial tasks, such as balancing the needs of the employer with the needs of workers, are to everyone's benefit. Providing a suitable work-life balance for employees while getting quality work done on time and within budget is strategic in that it results in greater employee retention and satisfaction. Managers engaging WFM systems properly facilitate greater productivity and improved attendance increasing customer satisfaction, sales, and overall revenue.

The basic tactical duties of the manager/supervisor consist of reviewing and approving time records, accepting/rejecting time-off requests, entering absence information, fixing errors (such as missed punches), applying rules to compute special payments, and creating and managing schedules.

Managers also work closely with employees who use the system to promote appropriate usage. After the initial orientation, management will be the primary trainers for employees. Training should reinforce company policies and timekeeping procedures, as well as compliance and system functionality.

With proper data entering the system, management can then monitor the flow of workforce data. Managers use this information to make calculated decisions that align with organizational goals, reduce payroll costs, and minimize compliance risk. Actively managing employee activity by checking time reports and shift assignments will reveal opportunities to reduce overtime and optimize productivity through schedule changes and shift swapping.

Moreover, depending on the managers and supervisors' role in leave administration, management can also be responsible for reviewing leave activity. This includes planned, unplanned, incidental (partial shift absence), and many other types of leave.

It is helpful to note that managers can and should be performing both tactical and strategic duties as a delegate of a superior. Management is to be instructed and updated on the company's strategic vision for workforce optimization so that it will be able to focus on procedures that achieve the appropriate goals.

It is not uncommon for timekeeping systems to come with preconfigured user roles. These “canned” user profiles should only be used as templates and should not be deployed unless carefully scrutinized for appropriate access to system functionality. Some of the features that should be carefully considered before giving managers access include move amount giving users the edit capability to revise timecard totals and move chargeable amounts to different cost centers, accounting designators, or even unpaid buckets of time. Payroll is a reasonable place to allow unlimited move amount functionality among users.

Another feature that should not be turned on is the ability for users to edit their own timecard. Pay code entries to categories of time that should be computed based on punch time, such as regular time, should generally not be allowed at the manager or timekeeper level to avoid pay inflation. Yet another capability that some systems present is approved overtime. This function puts overtime hours into a holding bucket until a manager approves the time. The very implication that managers use discretion in paying overtime is problematic and sets up a red flag during compliance audits. There are other functions that can be used to monitor overtime and meet compliance requirements.

Beyond the timecard there are features that may create a greater demand on the system than is essential. Allowing users to create and run ad hoc queries based on more than basic query-building tools can bring a system to its knees in the hands of a rambunctious user population. Granting every user the ability to generate multivariable queries and run them against large sets of data should be avoided. This function is reasonable for well-informed WAM-Pros, payroll, and system administrator users who are cognizant of system performance issues and efficient data extraction. Many systems allow predefined queries to be built and made available to the general users sufficient to meet their general needs.

When designing user roles within WFM systems consider what it takes for users to do their job, system performance, compliance, and the manageability of a large number of unique user roles.

(c) System Administrators

System administrators must understand an extensive range of workforce management features and functions, as well as how the organization's timekeeping system operates and interfaces with other systems. They will be the first group trained on new workforce management system(s), and may be responsible for training the rest of the staff on their role in the system. System administrators oversee the system to determine if it is operating correctly. These users monitor system performance, security, data integrity, and integration between systems. They also tweak the system on an ongoing basis and may be called on when help desk and payroll personnel cannot resolve system issues.

System administrators may be asked to modify reports and generate reports for people who do not have access to the system. They are the technical support group. Their responsibilities also include managing the hardware and networks that support the WFM applications and devices.

It is suggested that an organization has, at minimum, two system administrators even if the role is part time. This provides a level of quality control and check and balance as no single person should work without oversight in an important financial system such as WFM applications. Administrators play an important part in making certain that the WFM system is regularly operational. Having a backup fully trained and with the proper user rights or ability to gain access via a proxy user profile is also essential to maintain business continuity.

The system administrators shoulder the day-to-day responsibilities for proper security control. This job function consists of the configuration of the application security controls and subsequent management of security profiles and assigning users access rights within the application and devices. These users generally need access to the technical side of the application—the configuration and setup, monitoring tools, log reports, ports, license setup, interface, and table maintenance. They generally do not need access to edit employee timecards or schedules but should be able to view all parts of the system.

(d) System Owners—WMO and WAM-Pros

The system owner, preferably a WAM-Pro, has responsibility for the successful design and implementation of company timekeeping and pay policies, as well as determines the security protocols for each group of users. Owners may need to work to adjust policy and submit proposed system design change requests for approval.

System changes stem from many sources. One source is compliance requirements. Changes to labor regulation and contracts or audit findings can result in adjusting how the company records, for example, hours worked. Other change requests may be the result of review and analysis of workforce data and job cost/project tracking. Therefore, owners need access within their user role in the system to review system design and understand how data is reported and to review all records, modules and interfaces, audit tools, reports, and analytical solutions. Ultimately they are responsible for the data and end results.

(e) Key Stakeholders (CFO, CIO, VP HR, Payroll Manager)

Human resources, payroll, and executive leadership should also be included in planning for system security and controls. These users may have important information about regulations, protocols, and policies to be followed. These users should have access to at least view pay rule configuration, security controls, and the design functions of user on-screen workspaces so that they can properly assess whether the design is taking advantage of functions that would improve processing, security, and compliance. Some of these users may need to review and possibly edit records but should have limited access to change underlying system design and controls.

(f) System Designers and Support Personnel

When user access is considered risky, one way to lessen the exposure is to give users such as programmers and external consultants access to a development environment of the system. This is a duplicate of the production system complete with all of the set-up and user data. It is not the live production system, so changes and potential mistakes made while working in this box will not impact operations and payroll. In this environment a user can be given a much wider range of functional access with less risk. It is not uncommon for outside consultant resources to work in these environments in order to reduce any concerns about security and system performance. Making a change in a WFM system can sometimes cause the entire system to recompute every unlocked time record. This type of workload can cause a system to slow to a crawl. Therefore, the development box allows users to work during normal office hours, test changes, make and correct mistakes, and preserve the integrity of the live WFM system. These users typically require super user access to the setup of the application as well as the time and employee records.

(g) Business/Workforce Analyst

The individual in charge of business analysis and/or workforce analytics and business intelligence (BI) uses the workforce management system's reporting capabilities extensively. The analyst will be responsible for creating global report templates in and outside the WFM application for the use of managers, supervisors, and administrators. He or she may also test new report configurations to produce better data or gain new insight on different aspects of the workforce. In addition to creating reports, an analyst would thoroughly review specific reports that can reveal areas of high and low productivity, as well as possible payroll leakage or other important business drivers. Here is where the analyst will be able to propose policy, data, and system changes and measure the effectiveness of specific system processes and design.

(h) Report Writer

Report writer responsibilities vary among organizations. Some organizations employ a highly skilled report developer with the technical skills to create original reports using specialized reporting tools and software applications. The specific applications are dictated often by the WFM software and what report solutions it is designed to support. It is also driven by the ease of use and whether the report developer must also understand the database and the table structure of a highly complex WFM system. These users may require system passwords and system administrator rights to do their job in addition to user rights to create and install new reports.

For organizations that rely on report writers to tweak and customize canned reports that are delivered with the WFM system, the role can often be filled with internal resources with less technical skills. Some application providers offer training and mentoring to educate about resources on these tools so that employers can be self-sufficient in creating reports. These users will require specialized user roles to open, copy, edit, and install new reports.

(i) Internal System Auditor

The internal system auditor is responsible for monitoring audit trail reports for problematic and potentially fraudulent activity. Suspicions of fraud, time theft, or suppression of paid time, may be the result of a supervisor's claim or an employee's grievance. The auditor must have sufficient system access to locate and analyze system records, and audit trails, and use the data in reports to investigate such claims.

Internal audits should be apprised of security design decisions and inspect for the proper procedures. Auditors need view access to employee records and manager inputs. They may need greater query functionality and could perform their work in a development environment. They may also need to run reports and view system error logs, adjustment or historical edit records, comments, and schedule changes. Calendar views are also helpful to give auditors a quick glance into patterns of activity.

(j) IT

The role of information technology (IT) in a timekeeping system depends on the system's architecture and delivery platform. There are three common types of workforce management systems:

When selecting a timekeeping system, IT will play an important role in selecting the system environment that best suits the organization's technological abilities.

The SaaS environment requires fewer internal technical resources. The system is hosted for the employer by the system vendor and can be accessed via the Web using a common Internet browser. The system vendor houses and maintains the system and interfaces and is expected to provide technical support.

The hosted environment may require some internal technical resources. In a typical hosted environment, software would be installed on a user's computer while the main system would be hosted by the system vendor or a third-party hosting company. IT would assist in deploying the software across the company, as well as establishing proper communication between the software on each PC or laptop and the hosted system. If there are communication problems, it would be IT's responsibility to repair those issues, as well as communicate problems with the system vendor and hosting company if necessary.

The client-based model is also known as on-premise, meaning that the system resides on the company's internal network. IT would be responsible to work with the system vendor to successfully install the system on the company's hardware and networks. It would then be the duty of IT to deploy the system's software on employee computers. Through the life span of the timekeeping system, it will be IT's responsibility to manage the system, making sure that it is effectively operating on the network and that there is successful communication between software on employee computers and the system. During this time, IT should be properly backing up the data in the system as well, as it is crucial for on-premise systems in case of any issues with the network. IT is also in charge of upgrades, patches, and internal system synchronization as well as database maintenance and troubleshooting problems with devices, hardware, and networks.

IT may play a role in the system's security management, especially in instances where sensitive data is entering and exiting the workforce management system. The data exchange could be integration with a third-party system, communication with clock devices, or the use of Web services and/or synchronizing system sign-on with network sign-on (i.e., utilizing Microsoft Active Directory for system sign-on). Distribution of WFM system data can also pose a security risk. Reports printed out in hard copy may contain sensitive information.

(k) Collection-Device Administrator

Also related to IT is the configuration and maintenance of data collection devices, such as time clocks or telephony systems. The majority of these devices can be configured by nontechnical employees; however, there sometimes are problems—such as with an organization's firewalls or phone lines—that may require the assistance of someone with an IT background. In certain organizations, an internal or third-party device administrator will be responsible for these tasks.

(l) Managing Roles: The Big Picture

This section has explained the different roles that an organization should consider putting in place to deliver the proper controls and pursue maximum value from a workforce management system. The roles—and their subsequent duties and responsibilities, both tactical and strategic—are the key to capturing proper data, minimizing compliance risk, increasing employee productivity, and reducing payroll costs. The WAM-Pro makes certain that user expectations and access rights are clearly documented, communicated, and routinely reviewed and updated.

8.3 UNIQUE ASPECTS OF TIMEKEEPING SECURITY AND CONTROL CONFIGURATION13

A workforce management system contains an abundance of information relating to an organization and its employees. Some of it may be sensitive and require added protections to secure the privacy of employer and personal information (for more, see Chapter 16, “Privacy and Security”). An organization must establish security controls to safeguard this data. Security controls must also extend to system functionality, as improper use (both fraudulent and accidental) will have a detrimental effect on the accuracy of payroll records, labor tracking, and other workforce-related data.

Each organization should recognize the seriousness of a potential data breach involving the timekeeping, HR, or workforce management systems, and properly protect itself from such threats. One successful breach may result in undesirable consequences, including employees losing trust in their employer, the organization's reputation may be tarnished if the security breach becomes public, and various legal liabilities and remediation costs.

(a) Securing Personally Identifiable Information

Workforce management systems contain Personally Identifiable Information (PII), which can be any information about an individual maintained by an organization, including: (1) any information that can be used to distinguish or trace an individual's identity and (2) any other information that is linked or linkable to an individual. (Chapter 16 covers PII in more detail.) From a configuration standpoint inside the WFM system, if PII data is absolutely essential there are ways to limit who has access to see or edit this information. The first step is to limit who can view the information by designing proper access rights in each user profile. The next is to make certain that those who can view can edit if and when it is required. Also review whether PII data is excluded from system reports, too, as on-screen access profile setup many not necessarily prevent PII inclusion in reports. Another area to be careful about is delegation or proxy assignments. PII data should not be shared during a time when a manager is temporarily filling in for another manager unless essential to the tasks they must perform in the manager's absence. Users should be informed and evaluated on the use of PII.

(b) Configuring Security

During the initial security configuration, the process is organized through the use of security profiles. Security profiles are a set of application-specific settings that will be applied to a specific group of employees. These settings manage different points of control.

i. View Access

The first point of control relates to the data the user will be able to view. Examples include timecard data, pay data (where dollar amounts are used), job cost/project tracking data, leave information, and personal employee information. The settings for these data sets will restrict what screens and reports a user can select, view on screen, and execute to print.

Questions based on viewpoints of control include: What types of employee information will the user have access to? Is there any reason the user would need to be able to view the employees' rate of pay or hire date? Does the user need to view information (such as personal, timecard, or leave data) for employees who are not in his or her home department?

View access can also be for administrative users who provide system support and may need to see information in the system to troubleshoot its performance. These users are given view access to timecard and personal data as well as information about how the system is set up.

Workforce management systems should be designed to assign very discreet view-access profiles that grant view access to a variable array of elements within the system based on the user's particular role.

ii. Edit Access

The second point of control consists of the functions the user will be able to perform—in essence, where a user can go and what a user can do in the system. Edit access allows the user to make changes in the system. These changes may be to timecard or employee data or to the system setup. For example, only a limited number of users should be able to create or change pay codes.

Questions based on functionality points of control include: What types of changes or edits does the user need to make? Will the user be able to edit his or her own records? Should the user be able approve timecards? Will the user be able to accept or reject time-off requests? What scheduling functions will the user be able to use? Does the user need access rights to change configuration within the application? Does the user need to make changes to how the system interfaces with other systems?

In general, points of control are dependent on the user's job responsibilities, as well as the user's assigned location, department, and what records the user needs to access. For an advanced level of security, limit the user's access rights to only include the data and functionality that is necessary for the user to fulfill his or her duties and avoid delegating rights to users required to fill more than one role.

(c) Flexible Controls

Workforce management system security design is not based on absolutes. Flexibility is important to accommodate the variety of situations and tasks that many users encounter. For example, in many instances a manager would not need to see information related to employees in other departments or groups. Instead of completely limiting the manager's ability to view all unrelated employees, consider specific instances when that control could cause problems. In this scenario, it may be helpful when approving or rejecting time-off requests that the manager can view company-wide who is scheduled to take time off for that particular day. In scenarios such as these, configure different security levels for specific functions. Security profile design is enhanced when the roles and tasks are fully understood, thus configuring access that supports decision making and goes beyond the primary set of data and functions required for the user's home group. Well-designed security profiles deliver requisite security without negatively impacting productivity.

(d) Change Control

Automated workforce management systems handle a continually changing set of labels, rules, data, and reports. Many offer considerable self-service functionality pushing system updates to the lowest level of users (employees and supervisors). After the initial installation of a system, it is not uncommon for the employer to take ownership of ongoing system maintenance, design, testing, and promotions from one environment to another. Audit trails capture much of what is changed, but there can be gaps in the history of edits to system setup and data.

Deciding which inputs should be distributed to end users and which changes should be limited to only a few system administrators depends on a number of factors:

- Is the change global—affecting all users?

- Does the system provide a detailed audit trail of the change?

- Would errors in the input cause significant problems?

- Can the change be removed once it is saved or used?

- Is it likely that users would add many similar inputs for the same purpose?

- Does the change affect the calculation of pay or benefits?

- Could the change impact running reports or the collection and assembling of data out of the system?

Some examples of changes include adding a new department code, creating a personal query, adding a permanent comment to the list, inputting a schedule pattern, editing a pay code label, requesting a day off, modifying an employee's time punch, inputting dummy timecard data to test a new work rule, or revising an accrual rule.

Any type of permanent system change should require an approval, a quality verification, and be thoroughly documented. Changes to individual timecard records or user-specific workspace settings may not require a quality check but these changes should be approved and documented in writing or electronically. Records should include details about the records before and after the changes, the reason for the change, each of the screens and set-up selections changed, the name of persons making the changes, the date, the system environment (test or production database), and the approving party. In many cases such as with pay rule setup, the change is not independent and requires additional changes in the system (prerequisite and subsequent changes). These should also be noted. For example, a new bonus work rule may require a new pay code be set up first and the new rule and pay code must be added later to the access profiles and report setup utilities.

Any change affecting how pay is calculated within a rule or system setting should be handled with at least two individuals verifying the quality of the work and the following of procedures. Formal guidelines establishing who can approve and outlining the hand-off of changes throughout the process reduce the risk to the organization of unauthorized or erroneous changes.

(e) User Passwords

The importance of user passwords should not be overlooked. To secure the system from password theft and password sharing, utilize password requirements. Recommended password requirements include:

- A minimum of eight characters and include at least one uppercase letter, one numerical character, and one special character.

- Automatic expiration at a set interval of time, varying based on the access level of the user (the greater the access level, the more frequently the password should be reset). A general leading practice is forcing a password change every 90 days.

- Verifying user identity before resetting a password (in the instance when a user forgets his or her password). The exact procedures depend on the setup of the organization.

Options for identity verification include:

- Requiring password reset requests to be made in person with the presentation of photo identification.

- Requiring the user's supervisor to call and affirm the request.

- Utilizing a self-service password reset tool that uses customized questions for the user.

*Note: System passwords are also an important source of control covered later in this chapter under “Fraud, Abuse, and Payroll Leakage.”

(f) Single Sign-On

Certain systems, especially those of the enterprise/on-premise mode, provide the ability to sync system sign-on to automatically occur when an employee logs in to a computer (syncing with Microsoft Windows' Active Directory is the most common example). The result is that the employee can only access the system when signed in on a designated work computer—which is a helpful way to protect password security and lessen the number of passwords employees must remember. In this scenario, system logon password security should follow the recommended protocols just described.

(g) Automatic Time-Out

Automatic time-outs are a standard security measure to protect software systems after a set period of inactivity. By means of locking the application or ending a system session, these automatic time-outs provide a defense against intruders if a user walks away from the computer or clock device.

Setting the period of inactivity before automatic time-outs occur should maintain a balance of convenience and data protection. Inactivity limits can vary based on the assessed risk of the location.

Automatic time-outs on clock devices have the strictest limits, usually 15 seconds of inactivity. This is because clock devices normally have multiple users, are frequently used, and have a short average session duration.

When the system is running on a computer (either through a Web page or software application), a leading practice is to have the computer lock or session time-out after 10 minutes of inactivity. This is because computers generally have a single user and an extended duration of use.

(h) Badge Information

Many organizations require employees to carry an employee identification card that is used for both swiping for timekeeping and for building access, such as opening doors or entering a parking lot. It is important that the WAM-Pro logically considers what information is embedded on these cards. Some companies have learned this the hard way, as employees discovered that their required, company-issued identification card was embedded with sensitive information, such as the social security number. The information on these cards can be easily extracted using a barcode scanner, which is now available on many mobile phones. Such misuse could subject the employer and employee to significant risk.

8.4 RECORD-KEEPING REGULATIONS14

Under the FLSA, every employer is required to keep certain records on file for each employee. The following is a list of the basic records an employer must retain:

- Employee's full name and social security number.

- Address, including zip code.

- Birth date, if younger than 19.

- Sex and occupation.

- Time and day of week when employee's workweek begins.

- Basis on which employee's wages are paid (e.g., $9 per hour, $440 a week, piecework).

- Total daily or weekly straight-time earnings.

- All additions to or deductions from the employee's wages.

- Total wages paid each pay period.

- Date of payment and the pay period covered by the payment.

- Hours worked each day.*

- Total hours worked each workweek.*

- Regular hourly pay rate (reference Chapter 6 for determining pay rate).*

- Total overtime earnings for the workweek.*

* = Only for nonexempt employees

According to the FLSA, each employer shall preserve all employee payroll records, collective bargaining agreements, and sales and purchase records for at least three years. Recorded materials such as timecards, work and time schedules, and records of additions to or deductions from wages must be kept for two years. However, because deductions from wages can be the basis of wage hour claims going back three years (federal) or longer (depending on state laws), the leading practice is to preserve time and labor management materials for the full length of time that other time or payroll records are kept.

Each state has the option to follow the federal requirements, establish stricter requirements, or even create lesser or no requirements. For example, New York has a six-year statute of limitations for claims under the New York Labor Law and requires that payroll records (showing hours paid, etc.) are kept for those six years. It would be prudent, however, to also have other backup materials for the entire length of the statute of limitations as well. In California, wage claims are often accompanied by a claim of violation of the state's Unfair Competition Law (Business and Professions Code § 17200), which has the effect of extending the statute of limitations from three to four years. The rule the state legislature creates does not have to match the federal laws. Nevertheless, as with all other wage and hour requirements, the stricter of the two (federal or state) laws is followed in the event of an audit. To determine their particular set of requirements, it is recommended that employers research their specific state record-keeping regulations.

For many employers, it is common practice to keep payroll records indefinitely. Most never destroy records, but simply transfer to electronic and keep. But retention time frame is not the only concern around record keeping. Due to the personal nature of the earlier listed information—some would be classified as sensitive or Personally Identifiable Information (PII)—secure data storage also becomes an issue. Monitoring user access and security controls for this data is critical for employee protection. (See Chapter 16, Section 16.2 for more detail.)

This section describes FLSA record retention requirements only. The IRC and other government regulations stipulate additional record retention requirements. Before deciding on your specific record retention plans, a full evaluation of all record retention requirements that could touch time records should be made.

8.5 LEGAL AND STATISTICAL ISSUES15

This section turns to the issue of labor resource management and the laws related to that exercise. It also examines the use of statistical analysis and skilled use of data, primarily in a litigation context, and the ways in which they help examine the issues related to those laws.

(a) Fair Labor Standards Act

Since 1938, U.S. workers have been afforded certain protections under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA). This Act was enacted because Congress found that,

[T]he existence, in industries engaged in commerce or in the production of goods for commerce, of labor conditions detrimental to the maintenance of the minimum standard of living necessary for health, efficiency, and general well-being of workers

The Act went on to establish a wage and hour division within the Department of Labor, the administrator of which would be appointed by the president. The Act established certain minimum federal requirements of work hours, wages, and overtime for full-time and part-time workers in the private (both profit and nonprofit), federal, state, and local government sectors. Specifically, the FLSA sets the minimum wage and overtime rates employees must receive for their work, requires record keeping by employers, places restrictions on the types of work and hours children can work, and mandates equal pay for equal work. The FLSA also identifies which workers are covered by the act and which workers are exempt from overtime provisions.

Although employees have been afforded these protections since 1938, it has only been since 2001 that there has been dramatic growth in the number of disputes over these protections making their way into the great battleground, the courts. Figure 8.1 displays the increasing number of FLSA-related filings since 2000.

Figure 8.1 FLSA Filings: U.S. District Courts

Source: Judicial Business of the Courts, “U.S. District Courts—Civil Cases Commenced, by Nature of Suit, During the 12-Month Periods Ending September 30, 2007 through 2011,” Table C-2A, 3; http://www.uscourts.gov/uscourts/Statistics/JudicialBusiness/2011/JudicialBusiness2011.pdf.

(Reference Chapter 6 for more information.)

Employers may also want to pay attention to geographic trends when it comes to labor law. Review of the Federal Judiciary shows that Florida and California face a higher proportion of labor lawsuits filed in federal court in 2011, 14.3 percent and 9.9 percent respectively. New York and Illinois also have a high proportion of labor cases at 14.3 percent and 9.3 percent respectively. However, the likelihood of facing employment scrutiny is not simply a function of being in a populous state. For example, Texas saw only 5.4 percent of labor cases and Georgia only 1.8 percent in 2011.4

Not only have the number of cases increased in the past few years, so too have settlement amounts. According to the Seyfarth Shaw Annual Workplace Class Action Litigation Report, the top 10 settlement amounts in 2008, 2009, and 2010 were a combined $252 million, $363 million, and $337 million respectively. These settlements cross over many types of FLSA claims from misclassification of employees as exempt from FLSA laws, to donning and doffing. They also cover meal and rest breaks, overtime, and subcontractor issues. These settlements also cover a wide range of employers and industries, including retail, financial services, and transportation workers.5 Figure 8.2 details a few of the large settlements from recent years.

Figure 8.2 Wage and Hour Settlements

Donning and doffing refers to situations in which employees are required to wear protective clothing or equipment, which they must take time to put on and take off prior to and after a shift.

The Wage and Hour Division of the Department of Labor also reports having collected $185 million in back wages for more than 200,000 workers in 2008, a 40 percent increase from 2001.6 These statistics underscore the importance of properly compensating employees.

(b) Wage and Hour Issues

So what exactly do FLSA issues consist of? Lawsuits filed under the FLSA, or a state statute, are commonly referred to as wage and hour cases and typically cover:

- Misclassification of employees as exempt from overtime compensation

- Misclassification of employees as contractors

- Off-the-clock work

- Donning and doffing

- Time shaving

- Missed, late, and short meal periods and rest breaks

- Improper calculation of overtime compensation

- Improper deductions in pay

This chapter discusses these issues with a litigation framework in mind. However, these issues exist for employers, regardless of whether litigation is pending (or threatened). In addition to the legal issues that must be considered by attorneys, there are economic and statistical aspects that employers must address to determine whether there is evidence of liability, and if so, the amount of potential economic exposure. Examining the economic and statistical aspects of wage and hour claims typically requires labor economists or statisticians to understand the process at issue for the specific organization involved and to determine what data is available to quantify the issue. What data is commonly available to economists to examine a wage and hour claim? Often, the data that measure the incidence of alleged violations of wage and hour laws, or their duration, are not generally maintained by employers. As a result, researchers seek indirect information that may be used to provide estimates of the occurrences of the alleged violations. In most instances, economists begin with the record of daily and hourly activities of the employees' timekeeping records. Many companies, but not all, have adopted computer-based automated timekeeping systems, as discussed in other sections of this text. The payroll systems in these companies have also been updated to accept and process these data directly from the timekeeping systems. In other cases, time records may be manual timecards. Regardless, most examinations will begin with timekeeping/payroll data.

The accuracy of the data that are collected in these devices is contingent on the quality of data that are collected by these systems. In addition, the applicability of these data to the issues may be questioned. For example, if the issue is whether or not management permitted certain rest breaks, the timekeeping data may not be an appropriate source of information since management permission is not recorded—only the actual activity recorded by the employee is recorded. It is also important to note that it is unlikely that these systems were intended to be used in this manner.

Perhaps more importantly, though, is the issue of the accuracy of timekeeping data. In many instances, timekeeping data are collected when employees swipe a badge or log in to a computer to record the start or end of a shift or break. Consequently, the accuracy of these data depends in large part on the actions of the employees. For example, if employees routinely forget, or choose not to, swipe or log in, then these data are inaccurate and may not be useful for examining these issues. Conversely, if the issue is whether or not employees failed to receive a paid rest break, the data may be correctly recorded, but does not properly reflect the two different situations, one in which the employee took a rest break and one in which the employee did not. Existing laws typically do not mandate this specific type of record keeping. If the data reflect both shifts with a missing rest break and also shifts in which the rest break was taken but the employee did not swipe their badge, and thus these two types of situations cannot be distinguished, then the timekeeping data may not be useful unless some measure of accuracy can be developed.

In many instances though, alternate data may be available that is useful in (1) verifying the accuracy of the timekeeping data or (2) supplementing the timekeeping data when certain types of employee actions are sporadically recorded, or not recorded at all. There are a variety of devices and systems that time-stamp employees actions and allow an examiner to determine if an employee was or was not working. These include:

- Electronic building or location devices that report when employees enter and exit an establishment.

- Computer applications that record log-in and log-off activity.

- Price scanning and inventory devices.

- Point-of-sale transaction data.

- Cash register assignment entry data.

- Restaurant tip reports.

- Charge-card receipts containing time stamps.

- Vehicle GPS devices.

- Cell phone text data.

- Cell phone call data.

- Cell phone application data.

- E-mail.

In addition to the previous list, affidavits, declarations, and depositions of the company's decision makers can help to examine questions of whether the employer has a common process. This type of information can often identify differences or similarities in behavior or policy across employees, jobs, departments, and so on. This information may be critical for designing an analysis and/or interpreting results of an analysis. Similarly, affidavits, declarations, depositions, and surveys of employees may be used to analyze whether there are individualized or common circumstances that help to guide statistical analysis design and interpretation. Testimony from employees may also assist in determining the potential size of a litigation class and its composition (perhaps it encompasses employees in particular jobs, departments, locations, etc.).

(c) Statistics

Before detailing a few of the types of uses of the data just outlined, it is first helpful to discuss the importance of having reliable data in the context of statistics. Statistics is the study of the collection, organization, analysis, and interpretation of data. Usually, statistical analysis begins with the formation of a hypothesis about the question being studied or the concept being measured. Statistical analysis allows us to determine if a measurement of the concept from the available data is consistent with the hypothesis. In a statistical analysis, a good measurement passes these two tests of validity and reliability:

- A measurement is valid when it measures what it claims to measure without a systematic bias.

- A measurement is reliable if multiple measurements will give you approximately the same result time after time.

These concepts are illustrated in the graphs provided here. The true measurement (which is unknown) of the concept is represented by the center of the target and the repeated measurements from the available data are represented by the small circles.

In Figure 8.3, the repeated measurements are concentrated at the center (true measurement of the concept) and in close proximity of each other. Figure 8.3 represents valid and reliable measurements. The measurements measure what they are supposed to as indicated by the concentration of the measurements around the true value (valid) and the different measurements are close together (reliable since repeated measures give similar results).

Figure 8.3 Valid and Reliable

A valid but unreliable measurement is shown in Figure 8.4 where the different measurements are scattered around the true value (valid) but some are farther from the true value than others (unreliable). In this case, there is not a bias or a systematic error because the measurements are not different than the true value in a consistent direction. This type of error is called random error. Random error is evidenced by measurements that are scattered randomly around the true value. The reliability of the measure depends on the degree to which the measurements accurately identify the true value.

Figure 8.4 Valid but Unreliable

A measurement is invalid but reliable, as shown in Figure 8.5, when the different measurements taken are very close to each other (reliable) but are far from the true value (invalid). In Figure 8.5, the repeated measurements are consistently away from the true value in one direction, rather than scattered around the true value. The measurements in this case appear to contain a systematic error or bias, as opposed to random error, because the measurements are consistently away from the true value in a particular direction.

Figure 8.5 Invalid but Reliable

Finally, a measure may be both invalid and unreliable when different measurements are not consistently scattered around the true measure but are consistently on one side of the true value (invalid or biased) and the measurements themselves are not very close to each other (unreliable) as shown in Figure 8.6.

Figure 8.6 Invalid and Unreliable

If, for example, the purpose of a statistical examination is to aid in determining how many times employees missed breaks or worked off the clock, then the estimates of the missed breaks or off-the-clock work from different data sources should (1) measure the variable of interest (be valid) and (2) be reasonably close to one another (reliable). If the measurements from one data source, say timekeeping data, provide for a different estimate than say, e-mail data, then one must determine which of the sources provide a valid and reliable measure and which suffer from bias. Statistical analyses help the fact finder to visualize and understand the strengths and weaknesses of the various data sources.

(d) Use of Data in Wage and Hour Cases

To assess whether a particular measurement is reliable, it is beneficial to have another measure for comparison. In the context of wage and hour issues, this is often, but not always, a comparison of timekeeping data to some other data source. The specific type of data used for comparison is likely to depend heavily on the issue(s) at hand and the type of organization. For example, in the case of meal and rest break issues involving retailers, point-of-sale data may very well be useful. When the issues involve off-the-clock work for salespeople, e-mail and cell phone data may well come into play. For donning and doffing cases, there may be building security entry records or possibly video records. Other examples may involve restaurant servers and off-the-clock work at closing time or meal and rest break issues. In that instance, credit card transaction time stamps may be useful. In the case of issues involving delivery drivers, one might expect that GPS or other vehicle tracking devices could be useful. Although these examples provide some guide as to the types of data that can be useful in different situations, there are no hard and fast rules. Often, professionals are required to use creative thinking both in terms of what data to use and exactly how to use it.

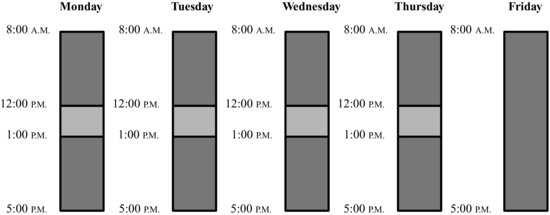

For example, assume a hypothetical examination of whether employees were systematically denied lunch breaks. A professional might first examine timekeeping data to determine if lunch breaks have been recorded and sees the following data detailing clock-in and clock-out times for a given employee (see Figure 8.7).

Figure 8.7 Timekeeping Data of Lunch Breaks

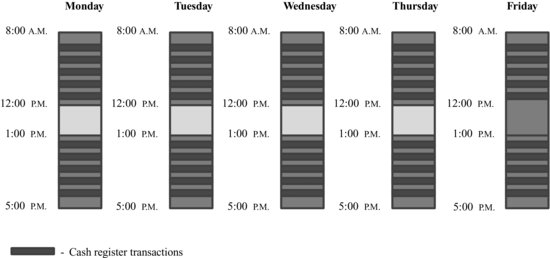

A professional might conclude that this employee received a lunch break of one hour each day Monday through Thursday, but did not receive his lunch break on Friday. The professional conducts a similar analysis on other employees and compiles statistics counting up the number of instances in which the timekeeping data do not show a lunch break. However, remember that timekeeping data only reflect time punches entered by the employee; they may not reflect what actually happened. A second professional examines the data and asks, What if the timekeeping data is inaccurate because employees forget to punch in and out sometimes? The professional then examines an alternate data source, for example cash register data. The professional sees the following data shown in Figure 8.8.

Figure 8.8 Cash Register Data

In this case, the professional sees the same pattern of data as before but has interlaced the timekeeping data with point-of-sale data. Like before, Monday through Thursday indicates a pattern of work followed by a one-hour break in which the employee punched out (and thus one presumes is not working) as well as a pattern of cash register transactions (point-of-sale data), which indicate a break (due to the lack of cash register data) during the 12:00 to 1:00 time period. However, Friday presents a conflicting set of data. According to the cash register data, the employee does not appear to be working between 12:00 and 1:00, just like on the other days. Alternatively, it may be that the employee was working but did not handle any transactions (which can be further examined by reviewing cash register assignment entry data). Regardless, there is clearly an incongruity between data sets that needs further examination. In this instance, the statistics from the timekeeping data alone may not be valid and it is important to examine other data sources to determine its validity.

It is also critical that professionals (or consultants in nonlitigation matters) determine whether particular claims are pervasive or limited to individuals in particular strata (job, department, location, etc.). Often, overall or company-wide averages mask the fact that a particular employment practice may be isolated to a particular group.

Again, assume a hypothetical example in which employees are denied breaks. Our first professional tallies the number of incidents of missed rest break swipes (from the available time swipe data) for all employees and concludes that missing rest breaks are prevalent among all employees. Our second professional enumerates the incidents by employee by store, and shows that the number of incidents of missing swipes varies substantially across individuals, stores, departments, and jobs. The distribution of the missed swipes can be tabulated by store to show the variations that may exist across these factors. For example, the distribution may show that missing swipes from a small number of stores accounted for a large portion of the total missed swipes (see Figure 8.9).

Figure 8.9 Percentage of Missed Rest Break Swipes

If the missed swipes were pervasive company-wide, the analyst would expect to see that roughly 20 percent of the missed swipes came from each quintile of stores. However, in this distribution, the stores with the most number of missed swipes account for 78 percent of the missing swipes, and 90 percent of the missed swipes are contained within the top 40 percent of offending stores. During the class certification stage, this is information that may lead a trier of fact (i.e., a judge or jury) to conclude that there is no company-wide class.

These types of examinations are not necessarily statistically complex. However, they do require that the person analyzing the data understand the nature of timekeeping systems and the other data that companies maintain. Often these systems, as described in other sections of this text, do not measure what they may have originally been designed to measure. In other instances, they measure exactly what they were designed to measure, but that measurement is different than what one seeks to explain, rendering the statistics invalid, unreliable, or both.

It is also important to understand that companies need not wait for litigation to arise before examining these issues. Implementing standard cross-checks of data systems and programming these systems to warn managers of violations when they occur, either through a reporting structure or in real time, are an important part of resource management. If companies do not maintain information that enables them to inspect the accuracy of their timekeeping data, it behooves them to find creative ways to ensure that they are FLSA compliant. Engaging outside experts to help in investigating these issues prior to litigation can save large amounts of attorneys' fees and reduce companies' exposure to punitive damages and bad press.

8.6 SSAE 16, SOC2, ISO, AND SOX16

Organizations need processes and controls in place to make sure that the products and services they deliver meet internal and industry standards. These may include compliance, service quality guarantees, security and confidentiality of data, transaction consistency, and a multitude of other performance criteria. To make sure that these processes and controls meet the requirements audits are typically conducted by third-party accounting firms to assess whether processes and controls meet an organization's objectives. Audits provide leading practice standards for a company to adhere to and offer a degree of confidence to current and prospective customers.

Some audits are regulatory, others are related to industry compliance and still others are voluntary events to address accounting and finance standards. Audit formats had been primarily developed for service organizations that support outsourced functions of client companies. For example, such organizations include application service providers, tax filing providers, payroll service bureaus, or credit processing organizations. However, today's employers are under increasing scrutiny to maintain compliance with a host of governmental, financial, and industry specific requirements. Organizations in public, nonprofit, medical, or government may be subject to regulatory requirements above and beyond what other employers experience.

Failure to establish and maintain suitable processes can have devastating consequences. Issues can range from having a company's technology infrastructure hacked to having data modified, stolen, sold, or taken advantage of. This section discusses three commonly known audit formats: Service Organizational Control 1 (SOC1), Service Organizational Control 2 (SOC2), and the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX), and relate how Workforce Asset Management professionals can make certain their organizations are doing things right.

(a) Audit Formats

SOC1, interchangeably referred to as SSAE16 (Statement on Standards for Attestation Engagements No. 16), stands for Service Organization Control Report. This audit standard supersedes the audit format known as SAS70. SOC1 is designed to consider whether a service organization has set up appropriate controls for financial reporting. This audit format can be suitable for private organizations providing payroll, tax compliance, or financial reporting.

The SOC2 audit format is designed to attest whether a service organization has set up and put in place the proper controls for determining the five principles associated with Trust Services, namely security, availability, processing integrity, confidentiality, and privacy. SOC2 is better suited for hosting companies and software platform or service providers.

There are two flavors of SOC1/SOC2 audits: Type 1 and Type 2. Type 1 is designed to attest whether a service organization has effective controls in place as of a given date. Type 2 attests whether a company has had effective controls over a time period, usually six months to a year. A SOX audit originated from the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 and is designed to confirm a similar set of principles as SOC1, but in the context of public companies. A SOX audit format is more rigorous than a SOC1 audit. Public company executives undersigned in the report may be found criminally responsible for errors and omissions. In addition, SOX compliance incorporates principles such as an auditors' independence and an analysts' conflict of interest, which may be outside of an audited company's scope.

(b) Audit Reports

Audit reports may be used internally by a company's board and auditors to assess the internal control risk for planning purposes and for executing other types of audits. Audit reports may also be used externally with current and prospective customers' auditors to get a more defined picture of a company's operating environment.

An audit may expose an exception in the design or effectiveness of control. For instance, one possible exception can be that a company's controls, designed to determine that security policy is adhered to by employees, are flawed.

Exceptions are reflected in the auditor's letter of opinion. Based on the nature of the exception and of the audited company's ability to remedy the exception, it may undertake the steps needed to fix it. Updates may be reflected in the body of a gap letter that the auditor team can provide between the formal audits. Consequences for failing to correct exceptions depend on the exceptions themselves. They can range from fines and management's criminal accountability to potential loss of clients and prospects.

(c) Audit Management

How organizations manage their audit processes depends on their size and type. Some may have compliance departments and teams dedicated to the audit process. Others may set up committees responsible for handling the process. Smaller organizations may appoint one or more people in a central portion of the organization to manage the process. This could be done via a corporate development team, COO, CIO, or WMO process. Finally, they can hire third-party consultants to manage the process for them.

(d) Role of the WAM-Pro

Workforce asset management professionals (WAM-Pro) experience direct exposure to many compliance-related processes and activities. The role of the WAM-Pro is to appropriately and consistently use Workforce Asset Management systems to make the compliance process easier and reduce employer risk.

The principal way to prepare for audits is to be organized. This means that policies must be kept up to date and reviewed annually. If changes are made, versioning can help in keeping track of ongoing development and improvements. Employee records must be consistent and current. Data should be digitized to make it easier to securely share with the auditor on request. The same message must be propagated across each level of the organization, as any inconsistency can raise red flags.