CHAPTER 13

Interactive Media and the Writer

CHAPTER OVERVIEW

This chapter defines important terms and explains the key concepts relating to interactivity, including:

- Interactivity vs. control

- Thinking interactively

- Linking

- High-level design

- Interactive devices

WRITE IT ALL!

Writing for multimedia and the Web may be the most challenging work you will ever do.

- Writing great prose text is not enough!

- Creating engaging video scripts is not enough!Writing audio like a radio pro is not enough!

- Making characters come alive with snappy dialogue is not enough!

As a writer for interactive media, you have to do all these things and more.

To be truly effective in this field, you will have to do more than write great text. The most exciting programs today go beyond click-and-read. This includes the latest generation of Web sites, as well as computer games, educational programs and other cutting edge interactive media.

To develop powerful interactive content, you will need to understand how to tame the complex structure of interactive media and write for video, audio, animation, and online applications. And, most of all, you will have to understand intimately each program’s users and the impact of their interactions on your content.

© 2010 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-240-81343-1.00001-7

Based on my experiences on nearly one hundred projects and on interviews with dozens of top experts in the interactive media field, I will describe how to master these skills and give examples from detailed case studies of successful programs. The case studies include professional interactive scripts, charts, and other documents that can serve as models for your own interactive writing assignments.

DefininG interaCtive multimeDia anD the interaCtive writer

Defning a Few Terms

Why “Multimedia and the Web” in the title of this book? I know the word police will complain that this doesn’t make sense, because multimedia is actually a common type of content on the Web. The words “multimedia” and “Web” are not mutually exclusive, I know. I agree, but many users still think of the Web as a place of mainly static pictures and text, while multimedia is the more interactive and media rich world of computer games, edutainment programs, and the like. I wanted to make it clear that this book is addressing the broad spectrum of interactive media content development.

Before we go forward, I should define how we will use the terms “multimedia” and “interactive media” in this book.

DEFINING MULTIMEDIA

As used in this book, “multimedia” and “interactive multimedia” are defined by four basic characteristics:

- Combination of many media into a single piece of work. Combining several media or modes of expression into a single integrated program or piece of work is one aspect of multimedia. Video, text, audio, and still pictures are all examples of different media or modes of expression.

- Computer mediated. In multimedia, a computer is used to mediate or make possible the interaction between the users and the material or media being manipulated. “Computer” is used here in the broadest sense, including computers in cell phones, game consoles, and other devices, as well as ttaditional PCs. No computer involved = no multimedia. A book with pictures is not multimedia.

- Media-Altering Interactivity. User interactivity in multimedia is best defined as “the ability of the user to alter media he or she comes in contact with … Interactivity is an extension of our instinct to communicate, and to shape our environment through communication” (Jordan). Blowing up an alien in a computer game is altering the media. Customizing your broker’s Web page so that it presents only the financial information you want is altering the media, as is visually creating your dream car on an automaker’s site. Shopping on television does not qualify as interactivity under this definition.

- Linking. Linking allows links or connections to be made between different media elements. This can be the menu links connecting different sections of a Web page, or the narrative links in a computer game that are triggered by the actions you choose for the character.

To sum it up, multimedia is a combination of many media into a single work where media-altering interactivity and linking are made possible to the user via the computer. This definition includes all the disc- and cartridge-based (CD, DVD, Xbox, etc.) programs and most of the Web sites in this book.

DEFINING INTERACTIVE MEDIA

“Interactive media” has ttaditionally been a much broader term than “multimedia.” “Interactive media” is used to describe all media with interactivity. It usually refers to computer-delivered interactive media, including both multimedia programs and non-multimedia interactive programs, such as click-and-read Web sites that have limited interactivity and no animations, video, or sound. This is how the term interactive media will be used in this book.

In short, interactive media is computer-delivered media or modes of expression (text, graphics, video, etc.) that allows users to have some control over the manner and/or order of the media presentation.

“MULTIMEDIA” AND “INTERACTIVE MEDIA" IN THIS BOOK

Based on the above definitions, I will generally use the terms “multimedia” or “interactive multimedia” in this book to indicate my major focus is on computer games, E-learning, training programs, Web sites, and other projects that use a combination of computer mediated rich media, complex interactivity, and linking. I will use “interactive media” to refer to all types of computer-delivered media with interactivity, including multimedia, such as computer games, AND simpler interactive media, such as pictures-and-text Web sites.

Types of Interactive Multimedia

The Web is a growing platform for multimedia. Material is presented on sites through multiple media, including pictures, text, video, audio, and animation. The user controls the flow of information and/or performs complex tasks. Examples of Internet rich media applications include interactive animated presentations explaining a product; financial calculators with opportunities to input data and see visual presentation in charts and graphs; product searches with text, audio, and visual elements that allow the user to see how their search terms affect product choices; E-learning courses with exercises, examples, and student-teacher interactions; and online games of all types.

In addition to the World Wide Web, multimedia is presented on local networks, such as corporate intranets; computer hard drives, such as museum kiosks; interactive television, such as MSN TV; dedicated gaming systems, such as PlayStation and Xbox; mobile devices, such as PSPs (Play Station Portables), iPods, and phones; and discs, such as CD-ROMs and DVDs. Interactive multimedia has dozens of uses, with the most common being marketing, sales, product information, entertainment, education, training, and reference material.

If you are completely new to multimedia and the Web, and feel you need additional basic information on these subjects, you may want to review the Background section of this book, which is available at http://booksite.focalpress.com/companion/Marx

The Role of the Interactive Writer

The interactive writer may create:

- Proposals

- Outlines

- Sitemaps

- Treatments

- Walkthroughs

- Design documents

- Scripts

- Other written material that describes a multimedia or Web site project

This can include developing the information architecture, on-screen text, overall story structure, dialogue, characters, narration, interface, and more. The key difference between writing for linear media, such as television and movies, and writing for interactive media is interactivity, which allows the user of the program to have control over the flow of the information or story material.

INTERACTIVITY VS. CONTROL

Potential Interactivity

Interactivity means that the user can control the presentation of information or story material on the computer. The potential interactivity of multimedia is awesome. It is possible to interact not merely by screen or page, but by controlling the presentation of individual objects within a screen, such as a single character’s actions in a scene, the color of a part of an image, or the presentation of a line of text.

Limits to Interactivity

There are practical limits to the potential of a particular user’s interactivity. The viewer’s equipment has to be powerful enough to support the level of interactivity. And even if the viewer has the best system in the world, if the source material is a CD-ROM, a DVD, or some other closed system, the player is working with a finite number of options. He or she can access only what the makers place on the disc. This limitation disappears when multimedia is delivered online, through the World Wide Web or an online service, which allow users to link instantly to thousands, or perhaps, millions of other sources throughout the world. However, for Web surfers who still use a modem, the slow download speed can make the online multimedia experience sometimes frustrating.

See the “Playback/Delivery Systems” article in the Background section of this book for a detailed discussion of this issue. The Background section is available at http://booksite.focalpress.com/companion/Marx

Is unlimited interactivity the most effective way to communicate with multimedia, if technically possible for the user? It depends to a great degree on what your goals are. If, for example, you are trying to tell a story, such as the interactive narrative Voyeur, the degree of interactivity you can allow and still create believable characters, intriguing plot, and suspense will be far less than if you are simply creating a world for viewers to inhabit, such as SimCity 3000. Similarly, a Web site with the focused goal of getting you to buy a car will have far less interactive options than an online encyclopedia that wants you to explore its information. Voyeur designer David Riordan echoes the feeling of many multimedia developers when he says that: “Infnite choice equals a database. Just because you can make a choice doesn’t mean it’s an interesting one.” He says that the creators of multimedia must maintain some control for the experience to be effective.

THINKING INTERACTIVELY

Thinking of All the Possibilities

The stumbling block for most new interactive writers is not limiting interactivity and maintaining control over the multimedia experience. Most new writers have the opposite problem of overly restricting interactivity and failing to give users adequate control over the flow of information or story material. This is because limiting options is what most linear writers have been trained to do. In a linear video, film, or book, it is essential to find just the right shot, scene, or sentence to express your meaning.

In writing for interactive media, “the hardest challenge for the writer is the interactivity—having a feel for all the options in a scene or story,” says Jane Jensen, writer-designer of the Gabriel Knight series. Tony Sherman, writer-designer of Dracula Unleashed and Club Dead agrees. Unlike a linear piece in which it is crucial to pare away nonessentials, in interactive media, the writer must “think of all the possibilities.”

Viewer Input

It is difficult to predict how the viewer will interact with all the possibilities in a piece. Jane Jensen warns that this can sometimes make multimedia “a frustrating and difficult medium … You have this great scene, but you have to write five times that much around it … to provide options. When your focus is on telling the story, that can feel like busy work and a waste of time.”

For example, you have a telephone in one scene that your player must dial to call his or her uncle and find out who the murderer is. This is near the end of the game and getting the telephone number itself has been one of the game’s goals. The writer needs to anticipate all the things players might try to do with that telephone. What if players get the telephone number from having played the game earlier, and they then jump ahead to the telephone scene? What should happen when they dial? Should they get a busy signal? What if they dial the number after they have gotten it legally in the game, but they don’t have all the information they need, such as knowing that the one who answers is their uncle? Should the writer give them different information in the message? What if they dial the operator? What if they try dialing random numbers?

This can be equally complex in an informational multimedia piece where you must anticipate the related information that the viewers will want to access and all the different ways they may want to relate to the key information. Compton’s Interactive Encyclopedia, for example, allows users to explore a particular piece of information through text, pictures, audio, videos, maps, definitions, a time line, and a topic tree. The design of the program allows all of these different approaches to be linked together if the viewer desires. This means that students studying Richard Nixon can mouse-click their way from an article about Nixon to his picture, to an audio of his “I Am Not a Crook” speech, to a video about Watergate and Nixon’s resignation, and finally to a time line showing other events that happened during his presidency.

Knowing the User

A key way to anticipate users’ input is to know as much about them as possible. This is also important in linear media, but it is even more crucial in interactive multimedia, because the interactive relationship is more intimate than the more passive linear one. Knowing the audience is absolutely essential. Knowing what the user considers appealing and/or what information they need will affect every element of a production, from types of links to interactive design.

On most multimedia and Web projects, considerable effort is put into researching the user. Some sources for user information include customer support lines, customer surveys and interviews, bulletin boards, salespeople, user groups, trade shows, and bulletin boards. This information is usually put together in a document called a User Scenario or a Use Case. A Use Case first describes the user and his information and entertainment needs. Then the user’s most common paths through the program to get information or complete a task are charted. This helps the designers understand how they need to present the content to meet the user’s needs. Before a major project is released to the general public, it is tested with small groups of users in usability studies. The feedback from these studies allows the developers to refine their information design.

LINKING

Links are the connections from one section of an interactive media program to another section of the same program or, if online, to a totally different program. When the information for a program or site is stored in a database, then the linked material can be even smaller or more granular. It is possible to link users’ actions to single program elements, sentences, or even words. The simplest link is a text menu choice that the user clicks to bring up new information. When writers develop links, they must make a number of decisions:

- What information, program elements, pages, chapters, or scenes will connect with other sections of the program?

- How many choices will the user have?

- Which choices will be presented first?

- What will be the result of those choices?

- Will the links be direct, indirect, or delayed?

Immediate or Direct Links: An Action

In an immediate or direct link, the viewer makes a choice, and that choice produces a direct and immediate response that the viewer expects. For example, on an investment company’s Web site, when the user clicks on the “Rolling Over Your 401(k)” link in the menu, they expect to and will get a page of information about 401(k)s.

Indirect Links: A Reaction

Indirect links, also called “if-then” links, are more complex. Users do not directly choose an item, as in the example above. Instead, they take a certain action that elicits a reaction they did not specifically select. The following example is taken from the walkthrough for the computer game The Pandora Directive. The walkthrough describes the program’s story and the main interactive options for the user. At this point in the story, you, the user, are trying to escape with the woman Regan, but you have been cornered by the villains Fitzpatrick and Cross.

Excerpt from the Pandora Directive Walkthrough

You get the choice of shooting Fitzpatrick, shooting Cross, or dropping the gun. If you try to shoot Fitzpatrick, you get trapped alongside Regan and Cross; then everybody dies, safely away from Earth. If you try to shoot Cross, he kills you before you ever get into the ship. If you drop the gun, you get to the spaceship.

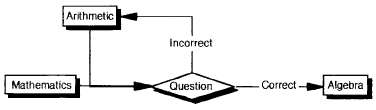

An example of an indirect link in an informational piece is a student who fails a test in a certain subject area and is automatically routed to easier review material, instead of being advanced to the next level. The student did not make this direct choice. It is a consequence of his or her actions. Figure 13.1 shows how a student who could not answer an arithmetic question in a math tutorial is sent back to an arithmetic review module as opposed to being advanced to the more diffIcult material. A number of educational multimedia programs work this way.

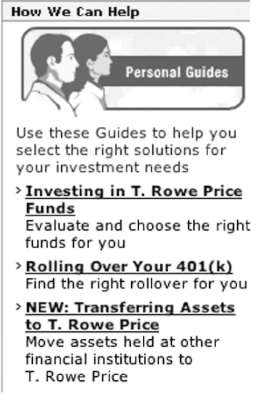

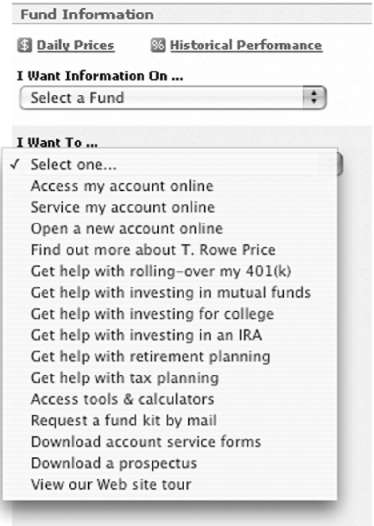

Indirect links can also cause multiple things to happen when the user clicks one choice. This is most common in a program or Web site where the information is dynamic because it is stored in a database. What this means is that the information is not static in large sections, like the pages and chapters of this book or a traditional HTML Web page. If this book was a database-generated Web site, every paragraph or sentence in it would be a separate piece of information. Depending on what actions the user took on the Web site, these separate pieces of information could be sorted, organized, and displayed in the order requested by the user. For example, on the T. Rowe Price investment company Web site, users can fIll out a form and establish the list of mutual funds and stocks that they are most interested in. After they have done this once, when they log on to the site in the future, they are activating a program that searches out the most current data on their topics in the database, organizes this data, and presents it to them.

In the T. Rowe Price example, the multiple actions (sorting, organizing, etc.) are finally displayed in one location, but a single indirect link can also create multiple actions throughout a site or program. For example, on a well-designed Web site for an auto dealer, when a salesperson sells a car and enters the fnal sales form into the system, the car is automatically removed from the display on the public Web site and from the dealer’s inventory list. The site might also automatically generate an email message to the customers thanking them for their business.

figure 13.1 A reaction to user input.

Intelligent Links or Delayed Links: A Delayed Reaction

Intelligent links remember what choices the user made earlier in the program or on previous plays of the program and alter future responses accordingly. These links can be considered delayed “if-then" links. In a story, intelligent links create a realistic response to the character’s action; in a training piece, they provide the most effective presentation of the material based on a student’s earlier performance.

In The Pandora Directive, for example, you as the player are a detective who is trying to get in touch with Emily, a nightclub singer. You meet Emily’s boss, Leach, well before you meet her. If you are rude to him, he mistrusts you. Later in the script when you try to rescue Emily, he will block your entrance to her room, and she will be strangled. If, however, you are nice when you first meet him, he lets you in, and you save her.

Certain Web sites record every click you make and gradually define your preferences. This allows these sites to personalize their presentation to you so that they only show you information and products of interest to you. One example is Amazon.com’s recommendation of new book titles to repeat users based on past purchases. The most sophisticated sites might also personalize the way the information is presented. For example, a user who always jumps right to the online videos would be presented with pages containing more multimedia.

HIGH-LEVEL DESIGN AND INFORMATION ARCHITECTURE

The complexity that interactivity and linking add to a multimedia project demands strong high-level design and/or information architecture for the program to be coherent and effective. High-level design determines the broad conceptual approach to the project, including the structure, interface, map, organizing metaphors, and even input devices. Information architecture or interactive architecture is the term usually applied to Web sites for the overall grouping of the information, design of the navigation, and process flows of online applications.

Structure as an Interactive Device

The overall structure of a piece is one of the main ways interaction can be motivated in a narrative. In the computer game Half-Life 2, scientist Gordon Freeman is on an alien-infested Earth and he must rescue the world from the evil he unleashed in the first Half Life. The player’s main interactions, which are motivated by this story, are exploring the barren futuristic world and (of course) blowing away bad guys. In another game, Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas, you play the role of Carl “CJ” Johnson who is returning home to find out why his mother has been killed. It’s not long before you/Carl are rebuilding your street gang in order to get to the bottom of the problems and set things straight. In the narrative informational piece A la rencontre de Philippe, the player is motivated to learn about Paris through the role of helping Parisian friends find an apartment. In another narrative information piece, The Oregon Trail, your task is to outfit a wagon, join a wagon train, and make the journey safely across the country. This basic premise inspires a whole series of user interactions with the program from buying supplies, choosing a team of animals for the wagon, and shooting deer for food on the trail.

The overall structure and navigation of a non-narrative informational multimedia piece is called the information or interactive architecture. Poorly structured information will cause the user either to fail to interact with the program at all, or to get confused and give up part way through. For example, good information architects know what information to put on the top level of the interactive program, such as a Web site’s home page, to engage the user’s interest. After hooking the user, this top-level information has to lead the user logically to the information that the user wants.

Interface Design

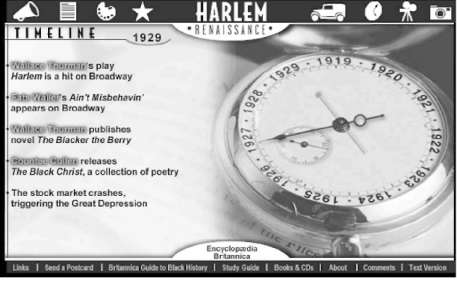

Another way to help users find their way through the complex structure of an interactive media production is through good interface design. The interface is simply the “face” or basic on-screen visualization of the information or story material in a program. The interface governs how we will interact with multimedia. An interface can be as simple as a list of words in a clickable menu that organizes the information into content categories. The interface can also be more graphical, such as the time clock and icons from the Harlem Renaissance site in Figure 13.2.

The interface can also be much more complex, such as the interface for the computer game Nancy Drew: Secret of the Old Clock computer game, which allows the user to interact with the story material in a variety of ways using items in the bottom tool bar and items in the main screen (Figure 13.3). From the bottom bar players can bring up the tools and clues they have found, consult their notebook, track their money, and get help. There are many more options in the main interface, including walking, driving the car, talking to people, solving puzzles, and using the telephone.

The amount of input the writer is allowed to give regarding the interface design depends on the designer and the project, but the writer must consider the overall interface design and information architecture when they are writing. Interface design is crucial in deciding how multimedia content will be organized. It affects the structure of the script for the writer and dictates how the viewer will interact with that content.

Figure 13.2 Timeline and icons from the Harlem Renaissance Web site. Copyright Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc.

Figure 13.3 Interface for Nancy Drew: Secret of the Old Clock computer game. Copyright Her Interactive, Inc.

The interface also affects the navigation of the piece—how the viewer can travel through the information or story and the order in which the information will be presented. The navigation is often demonstrated through flowcharts and diagrams, such as this flowchart from the Nancy Drew game (Figure 13.4)

The U.S. White House Web site (http://www.whitehouse.gov/) uses a simple hierarchical menu for navigation in which users can first choose from a number of global links in the top navigation bar. By clicking the link “First Lady” the user is taken down a level to the First Lady’s page, on that page you have a number of options including “Press Releases and Speeches.” Clicking that link will lead to a list of actual speeches, which you can click to read the speech “The First Lady’s Remarks After the Christmas Day Lunch.” So this is an example of a hierarchical menu where you had to drill down four levels to get to the First Lady’s speech you were interested in: White House Home Page —> First Lady Main Page —> Press Releases and Speeches Menu —> “The First Lady’s Remarks After the Christmas Day Lunch.”

Figure 13.4 A portion of the writer’s flowchart for Nancy Drew: Secret of the Old Clock computer game. Copyright Her Interactive, Inc.

Map or Sitemap

An element of good interactive design is a sitemap or map that represents the overall structure of a piece in a concrete manner. A sitemap illustrates how the player should interact with the interface and navigate through the program. It can be as simple as a text menu that lists all the key pages of a Web site, broken down by categories. Sometimes the map is a flowchart of the entire production, as in the Oakes Interactive training piece for Fidelity Investments retirement counselors. In this program, a student can bring up the flowchart of the whole program and access any area of it by clicking on one of the labeled boxes. The sitemap can even be a literal map, as in Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas, in which the player can consult a map of the cities that make up the island of San Andreas to get oriented and decide where to go next. (The actual interface of the game is a 3D animation of the town’s buildings and citizens, with whom the viewer can interact.)

Metaphors

For software developers, the metaphor is a concrete image or other element that represents an abstract concept, making it clear and comfortable to the user. Perhaps one of the best-known software metaphors is the desktop. Windows PCs and Macs present the abstract concepts of computer files, directories, and software as file folders and documents that users can arrange and work with on the desktop.

Metaphors are also used to design individual screens and navigational aids. According to designer Aaron Marcus, “consistency and clarity are two of the most important concerns in developing metaphors” (Marcus, 1995). Familiarity to the viewer is a third item that could be added. Consistency means that users should not use buttons as the main navigational tool on one screen and then suddenly have to switch to a different approach, such as clicking on pictures, in the next screen. Both of these are valid metaphors for linked information, but they are confusing when mixed. Consistent placement of the same types of information in the same place on the screen is also important.

Creating familiar metaphors ties into knowing your audience. A valid metaphor for the structure of an elementary school education CD-ROM or Web site might be a street in a town. This is something students are familiar with. It makes sense for them to click on a library to get information or a movie theater to see a film. On a micro level, a common metaphor is a book that opens. Click a dog-ear to turn a page. Click the table of contents to go to a chapter. Sometimes a metaphor can add to the mood of a piece. The Harlem Renaissance Web site uses a tourist metaphor to help make the user feel that they are visitors to another era. The metaphor is strengthened with items such as street maps, email postcards, and evocative full-page visuals. A common metaphor on many Web sites, including the latest version of the Prudential Verani site, is a stack of file folders with tabs that can be clicked on to access the content of another “fle folder” of information (Figure 13.5). All of these examples are concrete objects or concepts that help make accessing information more usable.

Familiar metaphors help orient viewers, but this certainly doesn’t mean that metaphors have to be clichéd or boring. Certainly a designer who can push the envelope without losing the audience should by all means go for it. There is lots of room to be creative. It is important to make even the minor elements of a production work well. For example, one of the frustrating things in multimedia is the “wait-state” image. Many programs are content to give the standard clock or hourglass, but there is no rule that the wait-state image cannot be fun. A.D.A.M. The Inside Story, an anatomy program, shows a skeleton with a cup of coffee. Some children’s programs have scurrying animals.

Figure 13.5 Home page for Prudential Verani Realty, showing file folder tab navigation metaphor. Copyright Prudential Verani Realty.

Input Devices

Writers might also consider how the users will input their responses to the program. Standard choices include the keyboard, mouse, game controller, guns, writing text on screen, and touch screen, but sometimes the input device can be integrated into the material. Instead of a mouse, the Guitar Hero game has a guitar you can play that helps you become a rock star, complete with visual action at six different locations, from basement parties to sold out stadiums. Redbeard’s Pirate Quest uses a model pirate ship loaded with electromagnetic sensors. Speech recognition is also finally coming of age, and this could have a major impact on interactive narratives. Even more exciting are the potential applications for multimodal interaction. “Multimodal systems process combined natural input modes—such as speech, pen, touch, hand gestures, eye gaze, and head and body movements—in a coordinated manner with multimedia output” (Oviatt, 1999). For interacting with complex multimedia programs, such as virtual worlds populated with intelligent animated characters, a multimodal system will be far superior to the conventional Windows-Icons-Menus-Pointer (WIMP) interface.

INTERACTIVE DEVICES

In addition to the high-level design elements, the designer and writer must develop specific interactive devices that will make users aware of the interactive possibilities they have created. These devices include icons, on-screen menus, help screens, props, other characters, cues imbedded in the story or information, and more.

Icons

In computer usage, an icon is a symbol that represents a command or an ongoing action. For example, the floppy disc image in the toolbar of many software programs indicates the Save function. An hour glass icon indicates that the computer is doing a process and the user must wait. Various types of icons are used for interactive devices. In Voyeur they are used to inspire viewers to look into the rooms of the mansion that are visible from the voyeur’s apartment. If the voyeur moves the camera over a room in which there is action to view, an eye icon appears. If there’s something to hear, an ear appears. If there is evidence to examine, such as a letter, a magnifying glass appears. Clicking on the icons causes the material to be presented. The Nancy Drew games do something similar with the magnifying glass glowing when an item is clickable.

In Britannica.com’s Harlem Renaissance Web site, icons are used to efficiently indicate the main sections of the site in the Web site’s navigation bar (Figure 13.2). The megaphone is for leadership, the page is for literature, the palette is for art, and so on. The meaning of the icons is clarified through the use of rollovers that show text labels when the mouse passes over one of the icons. In the Oregon Trail, icons on the bottom of the screen let the player/ traveler check the status of supplies and health for the group. The supplies icon shows a bag of four and some containers; the health icon has a medicine bag and medicine.

Be careful not to overuse icons or rely on obscure icons. Many icons benefit from a text label, and sometimes it’s better to skip the icons altogether and rely on text alone.

Menus and Other Text

The text menu and the navigation bar are traditional and still effective ways to access material in informational multimedia. In addition to static text, menus can also be presented as popup or drop-down menus that take less screen space (Figure 13.6). They only appear when the user clicks on them. Text links can also be highlighted directly on a page within the body text, as in Figure 13.2, where the names of important figures of the era are links to additional information.

Although text menus can work well in an informational piece, they can disrupt the flow of a narrative. However, some designers are willing to accept that disruption to achieve a high degree of interactivity. In Under a Killing Moon, written by Aaron Conners, menus allow the player a wide variety of action options, including look, get, move, open, and talk. The player can even choose the tone of the lead character’s dialogue by picking menu choices such as “Rugged Banter,” “Indignant,” and “Reeking of Confdence.” Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas will also use text to indicate actions for the user. Text will appear on the screen at key moments with tips, such as “Ride the bike.” or “Keep up with your buddy.”

Sometimes words on the screen are optional. In Under a Killing Moon, players can pull down an optional hints window. This helps orient them in the game and tells them their interactive options. Sometimes written material is integrated into the story itself. Shannon Gilligan’s Who Killed Sam Rupert? includes an investigator’s notebook that keeps track of what the detective/player has done so far in the game. The Nancy Drew games use a similar device. Many online transactions, such as an online account opening for a bank, also have optional help text or product information that the user can decide to access or not.

Figure 13.6 Drop-down menu from the T. Rowe Price Web site. Copyright T. Rowe Price Associates, Inc.

Props

Props are a popular interactive device. In Under a Killing Moon, the character can click on objects in the room to get information. Depending on the object, a player might hear a voice-over wisecrack about a painting, or even see a full-motion video flashback that shows the detective’s relationship with the object. In the educational CD-ROM Sky High, users can click on various props in a scene, such as toy helicopters and birds, to bring up additional information related to that aspect of fight.

Props that a character can actually use as they might be used in real life are particularly effective. In the educational game Zoo Vet, the player can use a wide variety of medical instruments to help sick zoo animals. The game Half Life 2 has a wide variety of props that the user can manipulate, which encourages interaction. For example, in one scene, the character has to pile a group of boxes a certain way to climb out of a window.

Characters

Characters are another way to guide interactions. Sometimes this is the primary function of the character. In the Nancy Drew games, telephone calls from her friends and father nudge her in one direction or another and give additional clues. In the same games, talking with most of the main characters inspire additional actions. The investigators in Who Killed Sam Rupert and Gabriel Knight both have assistants who remind them of appointments, give them telephone messages, or suggest people to talk to. Other characters, who are not primarily information givers, might say things that suggest a location to visit or a person to interview. This is often used in Half Life 2.

A character can also be used as a guide to lead the viewer through the material. This can be successful in both narrative and non-narrative pieces. For example, children’s educational programs frequently have characters that suggest what actions to take and what information to explore. The veterinary assistants in Zoo Vet perform this function by telling the player/veterinarian when their diagnosis and treatment is off track. Many training e-learning programs will have an expert guide you can call upon for advice when you are trying to complete a task. This guide is usually represented as video, graphics, text, and/or audio of a specific person who can be called upon for help and advice as if they were a live consultant. In the narrative videogame Astronomica, the daughter of the doctor who disappeared approaches you, the user, directly by banging on your bedroom window and asking you to help find her father. She leads you to her father’s lab, where she works on the main computer, and sends you into the exploratorium to solve the problems there. She also appears now and again on a small communications monitor in the exploratorium to give you tips and encouragement.

Challenge of the Interactive Device

The challenge of the interactive device is to design something that will motivate interaction without radically disrupting the flow of information or story material. A well-designed interactive device will not pull us out of the dream state of storytelling or disrupt our train of thought as we pursue information. In short, interactive devices must be well integrated into the material.

CONCLUSION

This chapter has provided a broad overview of some of the key interactive issues the writer must consider when developing a multimedia informational or narrative program. Although the elements discussed above, such as interface design, are not always under the control of the writer, the writer must understand these concepts if he or she is to write effectively for interactive media.

REFERENCES

Davenport, G. (1994). Bridging Across Content and Tools. Computer Graphics, 28, 31-32.

Halliday, M. (1993). Digital Cinema: An Environment for Multi-threaded Stories. Master’s thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

The Harlem Renaissance. (1999). Web site http://www.britannica.com/harlem.

Jensen, J. Telephone interview with the author, July 1994.

Jordan, K. Defining Multimedia. NOEMA Web site. http://www.noemalab.org/sections/ideas/ideas_articles/jordan_multimedia.html.

Marcus, A. (1995). Making Multimedia Usable: User Interface Design. New Media, 5, 98-100.

Oviatt, S. (1999). Ten Myths of Multimodal Interaction. Communications of the ACM, 42, 74-81.

Verani, P. (1999). Web site http://www.pruverani.com.

Riordan, D. Telephone interview with the author, June 1994.

Sherman, T. Telephone interview with the author, July 1994.

Rowe Price, T. (1999). Web site http://www.troweprice.com.