CHAPTER 19

Designing Simulation Stories from Tacit Knowledge

The idea of creating a learning simulation to teach the tacit knowledge of military leadership was employed in all three projects that Paramount Pictures did for the U.S. Military. But it was most explicitly employed in the final of the three projects, Leaders, which was developed for the United States Army in conjunction with the Institute for Creative Technologies of the University of Southern California. Looking at the methodology used in this project can give a good illustration of ways to develop simulations for leadership and other skills that rely heavily on tacit knowledge.

STORYDRIVE SIMULATIONS

StoryDrive simulations are those that follow the classic structure of a Hollywood story complete with hero, arc, goal, and obstacle. The participant takes on the role of the hero and sets off on a quest to fulfill that goal. As Robert McKee (author of Story) explains, every step toward the goal should be born out of conflict. To impose even greater demands on that model, especially for pedagogical purposes, we can now add the concept that the simulation should be outcome driven. Outcome driven simulations require that the steps that the hero takes be based on pedagogical objectives that move him or her not only toward the goal, but also toward better and better skills honed through the challenges of the simulation. It is the task of the author of the simulation then not only to construct the best possible, most dramatic story, but also to construct one that provides the challenges and opportunities needed to acquire and develop skills that refect the pedagogical goals. How do you do that?

© 2010 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-240-81343-1.00001-7

Identifying Tacit Knowledge

Stories are one way to identify correct performance. An easier way may be to find people who are really good at something and just follow them around with a notebook writing down everything they do. Debriefings after each session can then help zero in on the specifics of the tasks and may lead to a correct prescription of correct performance. But tacit knowledge in skills such as leadership and management are hard to identify when you see them and harder to define once you’ve found them. That is how stories can help. Asking an experienced leader to define leadership might get you a lot of nonconclusive ramblings, but asking that same person to tell a valuable story about leadership can draw out much better, more specific data.

Roger Schank, the noted AI researcher, suggests that people understand the world because they form mental models of it. These internal world pictures are continually revised as they discover new things. The major revisions in people’s mental models are so important that they tend to remember the details of what happened when they were surprised enough by something that it made them change their world view. The day the universe changed for them actually becomes a story that they tell their friends, and Schank and others have described the telling of these stories as a mechanism for collective learning. The day we were surprised to find out a very important secret of management we immediately told our fellow managers and we all learned. We keep telling that story and more people learn.

So a good way to learn about important skills like leadership is to go to a number of people who understand it and ask them to tell stories. Within the stories will be the essence of the surprise that changed their worldview. Within the stories will also be an implicit explanation of the old view that was changed when the revelation occurred. As a result of all this you should be able to learn two things:

- The naive, expected view of the way something should be

- The informed, experienced, and true way.

The process of building outcome driven simulations begins when you collect numerous stories about a subject which largely consist of tacit knowledge, and which involve the moment someone learns something about it, which was true even though up until that moment he or she was convinced that it was false. Here is a formula, which helps clarify that point.

Initially you would expect X.

But, with experience, you learn that the truth is Y.

Or to put it more simply:

Expectation = X

Truth = Y

So you have arranged a series of interviews with experienced leaders, you have pressed them for stories of situations where they were surprised by something that taught them a valuable lesson about leadership. Then you and the rest of your team have transcribed the interviews, analyzed them, and determined what was the expectation and what was the truth behind each story. The next step is to turn those stories into decision points based on the underlying lesson of the story. If you believed the lesson then you would do what the lesson said to be true, otherwise you would do the expected thing. Or, put another way,

If you were in a situation

And you believed the lesson of the story

You would do Y (what the lesson says is the truth)

Otherwise you would do X (what a novice would expect to do)

Here is an example from the Leaders scenario.

Situation: You are Captain Young and you have taken over the command of a food distribution operation in Afghanistan. Your subordinate officers have come up with a mission plan that they are very proud of. Later you are talking with an experienced officer outside of your command and he suggests that a different plan might be slightly better.

Novice choice: Accept the plan of the more experienced person and tell the subordinates that this is what they should do.

Expert choice: Stick with the plan developed by your subordinates.

Interestingly here, the key word in all of this is “slightly.” Since the proposed plan will only be slightly better, it makes more sense to give your troops the motivational lift they will get from carrying out a plan that they designed and selected themselves.

Sorting Out The Story

Once you have completed your interviews and boiled down the scenarios into decision points, organize them according to topic areas. Then validate the decision points by having them reviewed by highly experienced personnel in the positions that you are trying to teach. If there are stories that just don’t ring true or cannot be condoned no matter how true they may be, throw them out. In the case of the Leaders project we were fortunate to have two highly regarded members of the military training community reviewing our work and commenting on its accuracy and believability We were also able to cross check the work against the literature on the subject. Sternberg’s Practical Intelligence in Everyday Life had already documented an extensive study of the military and we were able to verify our data with the Integrated Framework for Tacit Knowledge in the Military that was part of the work. We were gratified to see that the 63 anecdotes that we had collected covered all the categories of tacit leadership knowledge spelled out in the framework.

Once your content has been sorted into groups and verified, you need to organize it into four to six chapters of equal size putting most of the situations relating to specific topics into the same chapter. In the Leaders project, the 63 decision formulations that were made by the creative team were sorted equally into five chapters that represented the five components of the mission: establishing a relationship with subordinates, mission preparation, dealing with threats, coordinating with superior officers, and successfully executing the mission.

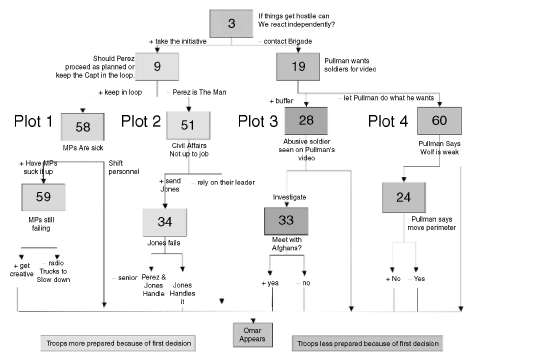

Building the Narrative

What we have created with the decision formula we have described is a binary system of choices where every decision requires that you make one or the other. These then lead to another choice between two points, which then lead to another choice. These choices can be assembled into a graph or flowchart that takes you from one choice to the next. Given the 63 original decision points and five chapters, we built a simulation that consisted of 12 to 15 choices per chapter. To round out the number of choices needed we sometimes repeated decision points, rewriting them so that the situations and the details of the situation were different. Figure 19.1 shows the structure of the graph for chapter 2 of the simulation.

Figure 19.1 Graph of chapter 2 of the Leaders simulation.

In the graph the first choice should be the most important instructional point in the chapter. This should happen for a number of reasons. First, the participants going through the simulation will all encounter this important point. If they go through the simulation again, they will always get this point again, so it is imperative that it be worth it. Second, this point leads to a major division in the action of the chapter, so right and wrong consequences of this choice can be most dramatic. Third, the challenge of this point will hit the participants when they are fresh in the chapter, most clear headed, with the least baggage from previous decisions. It is the most highly focused moment in the chapter, the best chance for undivided attention and dedicated response. Fourth and finally, this is the point by which the participants will judge the entire chapter. The quality of the insight gained at this point can motivate the participants to carry on through the rest of the exercise.

Once the initial point has been made, the decision points that follow should be arranged in clusters based on their content and the personalities involved in the decision. Events should be chosen that match the kind of decision required by the point, and they should be grouped together so that the same characters and location can be featured. As we talk about developing characters we will point out how complex personalities can add great value to story-based simulations. The trick is to recognize opportunities to use the same character to deal with a specific point. Then find decision points that would ft in logically with the situation presented in the simulation. One way to handle this is in brainstorming sessions with a number of participants: a writer, an interactive designer, a subject matter expert who can mix and match decisions with situations and personalities. It is generally not necessary to retell the story on which the decision point is based, but rather to look at the new scenario and try to figure out what kinds of events within the scenario could put the hero into a situation where this particular kind of decision would be necessary. Then review the other decisions and see if there is one that can build on the previous decision with the same characters and location, but with new events and revelations. It ends up being like assembling a jigsaw puzzle, but one where you are creating the pieces as you go along. Once a good event is developed it may not be a perfect follow-on to the previous decision point. If that is the case, set it aside and hold it for a more appropriate moment later in the simulation.

As noted previously, Leaders was based on a film about a food distribution operation in Afghanistan. That was the framing device for all the decisions that would follow. In Leaders, an initial meeting with Executive Officer (XO) Lieutenant Perez at the start of chapter 2 tests the Battle Captain’s ability to handle the first challenge to authority. Perez wants to run the operation. If the participant gives in to Perez, why not let Perez come back and challenge the Battle Captain even further? We found two important decision points about challenges to leadership authority among our 63, staged them at the same place and time, and put them into the hands of Lieutenant Perez. In the process, we made the simulation more interesting, the characters stronger, and the skills more highly exercised.

Dead Ends And Shared Outcomes

Two well-established techniques used in branching storylines are Dead Ends (if there is no outcome to a decision, simply say, “Sorry you’re wrong. Go back and try again”), and Shared Outcomes (decisions can lead to many outcomes, not just the two pre-planned outcomes specified in the flowchart). Dead Ends provide immediate feedback for the participants, but they destroy the sense of story flow and immersion. For that reason we did not use them in Leaders. Shared Outcomes give the participant more choices, but they disrupt the clustering of content that we have just described. The net effect is less dramatic tension and a decreased ability to add levels of meaning that result from highly structured exchanges extended over several decision points. For this reason Shared Outcomes were also not used.

Once the design team creates the basic structure of each chapter, the writer takes over and writes the script for the entire chapter, composing character conversations that present decisions and offer feedback. It is also important to write bridging material: additional scenes featuring other characters that set up each decision point and its problem and later comment on its success or failure.

A sample of the final script follows. It builds on the example that we cited earlier involving the decision regarding implementation of a plan put together by Captain Young’s subordinates.

Begin decision point 24

EXTREME LONG SHOT of distribution area showing terrain, converging roads, and position of troops setting up food distribution and security areas.

COMMAND POST

CLOSE UP: COMMAND SERGEANT MAJOR PULLMAN Pullman

looks down toward the roads.

PULLMAN

Look, I don’t want to go stepping on any toes, but I was looking over your terrain. I’m sure this site got chosen because of the road access. But it’s sure got some problems.

He points toward the perimeter.

I would encourage you to bump your security perimeter eastward, and put more distance between the wire and the road. Even after you’ve checked a vehicle through, damn thing could surprise you. That extra distance between the road and the perimeter could make the difference.

He points toward a rocky overhang.

PULLMAN

I’d also advise you start setting up the space under that overhang, in case it rains.

JONES

Captain, myself along with the XO and Second Platoon, we put a lot of thought into this configuration. Not saying the Command Sergeant Major has an inferior plan. But company personnel collaborated very closely in strategy and tactics.

PULLMAN

Captain, your First Sergeant heads a great team—but if you make these changes, it’ll pay off. Just give it some thought.

Pullman

leaves the Command Post. Jones turns to the Captain.

JONES

Would the Captain like changes made to the security perimeter?

Figure 19.2 Final Leaders simulation scene showing Jones and Pullman addressing Captain Young while Perez looks on.

SUMMARY

In this chapter we have shown how tacit knowledge can be acquired by collecting anecdotes about hard-to-defne skills like leadership. We also talked about how these anecdotes can be turned into teaching points, validated, and organized into chapters. We offered insight into the creative process that takes teaching points and turns them into story events and script elements. Finally, we showed examples of decision points set in a story context by providing examples from the Leaders simulation (Figure 19.2).

In the next chapter we will consider how to begin giving the participants a greater sense of free will within the context of the simulation story.