CHAPTER 17

Interactive Multimedia Narrative and Linear Narrative

Portions of this chapter originally appeared in the Journal of Film and Video.

CHAPTER OVERVIEW

A narrative is what we commonly refer to as a story. An interactive, multimedia narrative allows the user to explore several variations of a story or stories. Interactive narratives are produced for game consoles, PCs, mobile devices, the Web and interactive TV. Interactive narratives share many elements with linear film and video narrative. Because of this, it is useful to understand the basic elements of linear narrative before exploring the intricacies of interactive narrative.

NARRATIVE AND INTERACTIVE NARRATIVE DEFINED

A narrative is what we commonly refer to as a story. A “story” is one of those terms that we intuitively understand but are hard pressed to define. Critics have written many books defining narrative, but for our purposes we will define a narrative as a series of events that are linked together in a number of ways, including cause and effect, time, and place. Something that happens in the first event causes the action in the second event, and so on, usually moving forward in time.

Narrative interactive multimedia involves telling a story using all the multimedia elements we’ve discussed in previous chapters, including the use of media and interactivity. In narrative multimedia, the player explores or discovers a story in the same way the user explored information in the programs discussed in the previous part of the book. Often the player is one of the characters in the story and sees action from that character’s point of view. But even if he or she is not a character, the player still has some control over what the characters will do and how the story will turn out. Interactive narratives can be used for pure entertainment or to present information in an experiential way.

© 2010 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-240-81343-1.00001-7

INTERACTIVE NARRATIVES VS. SIMULATIONS AND WORLDS

A narrative or story is an ancient form of communication, but multimedia can also utilize newer forms that are sometimes confused with narrative. These new forms are simulations and worlds structures. Game and Web designer David Riordan points out that an interactive narrative, a simulation, and a worlds structure are three distinct forms.

In a virtual world program, the player explores an environment. Examples include the classic Myst and the more recent online multiplayer games, such as World of Warcraft. The designers of a virtual world create a physical space, such as a mysterious island or an entire war-ravaged mythical world, where the player has the freedom to move about and interact with various elements, opening doors, examining objects, talking to other characters, and even completing noble quests against mighty enemies and monsters. Worlds programs are not narratives, even though some of the characters and locations may have background information presented about them.

In a simulation, such as The Nauticus Shipbuilding Company or Amped 3, a player explores all the different possibilities in an activity, such as building a ship or going snowboarding. Simulations are not narratives. Even if they have a script attached to them, if the elements in the program come up in a random pattern, they do not comprise a narrative.

In an interactive narrative, a player explores a story. Interactive narratives have beginnings, middles, and ends, even though each user may experience these elements differently. There is nothing unplanned in an interactive narrative. Someone who plays the program long enough will eventually see all the material the writer created. An interactive narrative essentially allows each player to discover the story in a different way. The Nancy Drew mystery games are excellent examples of interactive narratives.

Simulations, worlds, and narratives can, of course, be combined and that is the most common way they are currently presented. Dust: A Tale of the Wired West integrates a narrative into the virtual world of a desert town in the old West. Just Cause takes the same worlds approach by making the player a secret agent whose goal is to overthrow the government of the island of San Esperito. The island is a fully developed world that the player can explore and interact with. Amped 3 takes a different approach and combines simulations and narrative by adding story segment to the snowboarding simulation. Although the original Sims game was closer to a pure simulation of building a house and creating a family, Sims 2 creates a more elaborate world for the characters to inhabit and becomes a combination of a simulation and a worlds structure. Many shooter games such as Shadow of the Colossus will also add a little story to help set up the action. In the beginning of this game, you are told that the only way you can save your true love is to hunt down and destroy sixteen colossal beasts. Once the setup is in place, the vast majority of the rest of the game is shooting the monsters. All these combinations are valid entertainment, but in this book our focus will be on games where the narrative is the primary, or at least major, component.

COMPUTER GAMES AND VIDEOGAMES: DEFINING TERMS

One of the indications that the interactive media industry is still in its infancy is that even some of the most common terms are not clearly defined. For example, some writers use the phrase “computer game” to mean any game played with a computer involved. This would include all consoles (PlayStation, Xbox, etc.), PC computers, mobile devices, interactive TV, and arcade games. Clearly the Web site “Computer Games Online” uses the phrase this way, because their content deals with all types of games. Other writers, however, think “computer game” just refers to games played on PC computers and not consoles.

The phrase “videogame” has similar conflicting definitions. Some writers think of a videogame as any kind of game using a video display. This would include all consoles (PlayStation, Xbox, etc.), PC computers, mobile devices, interactive TV, and arcade games. Electronic Arts, one of the biggest publishers of electronic games, is using the phrase this way when they title their site, “EA—Action, Fantasy, Sports, and Strategy Videogames.” However, other writers think of “videogame” as just applying to console games that are played on the TV and do not include games played on personal computers or a mobile devices.

There is even a third phrase, “electronic games,” that also applies to all types of video and computer games. But this term is being used less than the other two terms so will not be used in this book.

In this book, I will use “computer games” and “videogames” synonymously to mean all types of electronic, computer powered games, including those played on consoles (PlayStation, Xbox, etc.), PC computers, mobile devices (phones, PSP, Game Boy, etc.), interactive TV, and arcades games. I think this makes good sense because many games can be played both on a console and on a PC. Having two different names for the same game makes no sense. If I wish to distinguish that a game is played on a personal computer, I will call it a “PC game.” If I want to point out a console game specifically, I will use “video game console” or just “console.” For games on mobile devices, such as phones, PDAs, PSP, etc., I will use “mobile game.” Just keep in mind that this is the usage in this book, but the final definitions of all these terms are still in flux and may be slightly different elsewhere. So be sure you know how the terms are being defined in a specific context.

INTERACTIVE MULTIMEDIA NARRATIVES

Interactive Multimedia Narratives Genres

Although, there have been some interesting interactive narrative experiments both online and with interactive TV (CSI Interactive, Homicide: Second Shift, etc.), currently the most sophisticated commercial interactive multimedia narratives are found in video games. But a distinction needs to be made between games that simply have story elements and those that have fully fleshed out narratives. Marc Laidlaw, the writer of the action-adventure games Half-Life and Half-Life 2, explains it this way:

If we distinguish stories from storytelling, I’d say that lots of games have stories, but not many games do a good job of storytelling. A story can be very simple, summed up in a screen or even a single line of text. You read it, forget it, and wade into the game. But storytelling is the deliberate crafting of a narrative, with attention to rhythm and pacing, revelation and detail.

The major types of games that include story elements are action games, role-playing games, and adventure games, with adventure games being the only genre primarily devoted to storytelling. The main focus of action games, such as the Doom, Quake, and Halo franchises, is speed and action that usually takes the form of shooting other characters or blowing things up. These games are also sometimes called shooters or FPS (first person shooters). Role playing games (RPG), such as the Baldur’s Gate franchise, involve a character taking on a role and exploring a world, usually as part of a mini quest with limited story interaction and development of other characters. A subgenre of this game is the Massively Multiplayer Online Role Playing Game (MMORPG), such as World of Warcraft, that can involve hundreds of thousands of people at one time via the Web.

As Aaron Conners, the writer of the games Amped 3 and The Pandora Directive explains, in an adventure game, telling the story is the primary focus. There are strong characters and sophisticated story development. Characters overcome obstacles to achieve a final quest. Puzzles are also an important element. Nancy Drew: Secret of the Old Clock, The Pandora Directive, and Dust: A Tale of the Wired West are all adventure games, with Nancy Drew being in the mystery subgenre. The appeal of the mystery and adventure story is clearly that they are strongly goal-oriented. The player has something to aim for, obstacles are easy to establish, and jeopardy is built into the genre.

The Current State of Interactive Narrative and Computer Games

After a golden age of story-based adventure games in the mid-1990s, adventure games fell on hard times. Some interactive narrative adventures were poorly done and perhaps deserved to fail. But a number of adventure games with sophisticated stories, such as Grim Fandango, were released to rave reviews and critical acclaim and still did very little business. Because of this, many game publishers turned their backs on interactive narrative to focus on action games. Fortunately for lovers of interactive narrative, one of these action games, Half-Life, became a smash hit by including more story elements than a typical action game. Although the Half-Life story is fairly linear and the game is more action game than interactive narrative, it did show that there was still a hunger for stories in the audience. Half-Life’s success made popular the hybrid genre action-adventure—a game that has extensive action elements and a story. Most action-adventure games of this period did not have the sophisticated stories of the classic adventure games of the mid-90s, but they at least pointed the direction for the creation of commercially successful interactive narratives.

The major elements of this new direction for interactive narrative were the combining of different game genres and including more mature content and story elements. But other factors in the industry have also helped strengthen the resurgence of interactive narrative. A key factor is the introduction of the latest generation of game consoles that are capable of presenting content in a more cinematic and realistic fashion. This new capability has helped improve the success of Hollywood and game tie-ins and increased the convergence of narrative film/TV and the game industry. Another factor in more successful interactive narratives, particularly those tied to specific movie properties has been the involvement in games of major film narrative talents, such as Peter Jackson and Steven Spielberg.

All of these factors have produced a new wave of computer games with extensive stories. Although many of the stories appearing in the current crop of games are fairly linear and allow limited interactivity for the user, there is at least a definite interest in including story in games and a growing willingness to experiment with narrative. A few examples from various game genres follow. The Chronicles of Narnia, Pirates of the Caribbean, and The Godfather are all tie-ins to successful movie stories. The controversial Grand Theft Auto franchise combines an elaborate urban world the user can explore with mature themes, violent action, and a narrative. (This author is not endorsing the violent content of the GTA games.) Half-Life 2 and later games in that series followed the direction set by Half-Life but with a more complex world and story. Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney successfully brought the point and click adventure game to mobile devices with great writing and humor. Amped 3 integrated story into a snowboarding sports sim. The Nancy Drew mysteries are based on the successful books of the same name and are aimed at a female audience. Indigo Prophecy (also known as Fahrenheit) has true multipath scenarios where the story changes depending on user choices.

Matthew Costello, the author of The 7th Guest, one of the most successful story-based games ever, agrees that there has been a renewed interest in adding story to games. According to Costello, game companies have realized that story, characters, and dialogue are important components. They are hiring more writers with a grasp of narrative, and they are starting early with the story script, instead of just adding story elements to a game after the fact. His own writing talents have been much in demand with contributions to Just Cause, Pirates of the Caribbean, Shellshock, Doom 3, and The Italian Job.

With the game industry in general looking healthy because of long-term growth in console and mobile games, the outlook for the production of more games with story elements and complete interactive narratives looks strong. There is even some hope that weaker areas of the industry will strengthen. PC gaming has been the one game area in decline, but Microsoft’s latest operating system is being billed by the company as the most game-friendly operating system ever. Microsoft has also vowed to put its muscle behind the creation of more PC game titles. And there is even hope that the perennial dark horse, interactive TV, will reach its potential. Digital cable, video on demand, and interactive television (iTV) services are now available at some of the largest cable providers. Now we just need iTV programming to match the technological advances.

Larger game budgets; more powerful consoles capable of a realistic, cinematic presentation; Hollywood convergence and story talent; blended game genres; a willingness to experiment with narrative in games; and broadband speeds on mobile devices and the Web, allowing presentation of video and animation all point to a promising future for the interactive narrative.

CLASSICAL LINEAR NARRATIVE ELEMENTS DEFINED

Although there are many different types of narrative, such as realist and modernist, successful interactive narratives have largely focused on classical narrative, the same type of narrative that dominates linear film and video. Because of this, interactive narrative shares many of the elements of narrative film and video. As these are forms that most readers are already familiar with, I will first review the basics of classical linear narrative in film and TV before diving into the intricacies of interactive narrative.

Character

Classical linear narrative film and video are character driven. It is the character who grabs our attention and whose situation we are drawn into. Most successful film and video today clearly define their characters early in the piece. Who are the characters? Where are they from? What do they want or need, and why do they want it? What the character wants usually provides the action story of the film or video; why they want it provides the motivation for the actions and the underlying emotional story.

As an example, the modern classic film trilogy The Lord of the Rings establishes the lead character Frodo as a sincere, loyal, innocent, and cheerful nephew of his more adventurous Uncle Bilbo. We learn all this information about Frodo through the simple clothes he wears, his interaction with friends, his own actions and statements, and the setting. The first time we see him, he is reading a book under a tree in a peaceful orchard. When he first hears of the power of the One Ring, he immediately wants to give it away to Gandalf. A little later he tells his adventurous uncle, “I’m not like you.” But when it seems that no one else is suited to be ring bearer, Frodo does reluctantly take on the role. What Frodo wants in the film (his action need) is to destroy the One Ring, forged by the Dark Lord. Frodo wants to do this to save the Shire, but he also would like to prove to himself that he has the internal courage to accomplish the task. If we are going to care about the story, it is important that we identify with this character and his needs. Identification can be achieved in a number of ways, including casting an appealing actor, creating sympathy for an underdog, and having the character do positive things. The best way to achieve identification, however, is to develop the character so that the audience clearly understands the character’s needs. The Lord of the Rings does all of these things to get us onboard with Frodo.

Structure

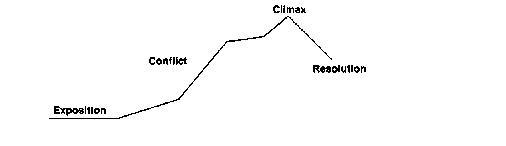

Once the character’s needs are established, the writer can begin to structure the script. The key elements of classical narrative structure are exposition, con-flict, climax, and resolution. Figure 17-1 lays out the basic structure of the vast majority of film and TV shows produced today.

Exposition or Setup

The beginning of the story must set up the lead character, the setting, and what the character wants—the goal to be achieved or the problem to be solved. Current films and videos tend to limit pure expositional sequences at the beginning and jump right into the story, integrating the story with the exposition. Some pieces open with an action scene and then slow down the pace in the next scene for exposition. However it is done, near the beginning of a script, the audience must learn who the character is, where he or she is, and what he or she wants.

Figure 17.1 Classical linear structure.

Conflict

Once the writer knows the lead character and his or her goal, then he or she can start the character on the way to achieving that goal. Of course, if the character achieves the goal in the first scene, it will be a very short story. To avoid this happening, the writer introduces conflicts or obstacles. There are three basic types of conflict:

- Person vs. person.

- Person vs. the environment.

- Person vs. self.

In The Lord of the Rings example, there are many “persons” who oppose Frodo, particularly Gollum, the orcs, Ring Wraiths, Lord Sauron, and all their minions. The environmental obstacles include mysterious forests, snowy mountains, labyrinthine mines, and much more. The last type of conflict, person vs. self, is a way of adding considerable depth to a piece. In the case of Frodo, he has serious self-doubts about his ability to carry the task to completion. These doubts are exacerbated by the evil power of the ring itself.

A number of writing critics, particularly Syd Field in Screenplay, point to a key plot point or event in the exposition that shoves the character out of the exposition and into the conflict. In Frodo’s case, it occurs at the secret council in the elf land of Rivendell when he takes on the task of carrying the ring to Mordor to destroy it. Once the conflicts begin, then each conflict or obstacle should be more challenging than the last obstacle so that the story rises in intensity.

Climax

Finally the story nears the peak of intensity, and a final event jacks it up to the climax, which is where the character either achieves the goal or not. In Frodo’s case, the final event is at the fires of Mordor when Frodo finally reaches his destination. However, because of the power of the Ring, Frodo has been corrupted and is unable to throw the ring into the fire. It is only by chance that another character, Gollum, tries to seize the ring for himself and ends up accidentally plummeting into the fire with the ring. With a little help from Gollum, Frodo has accomplished his physical goal of destroying the ring, but ultimately failed to accomplish his emotional goal of proving he has the strength to withstand the seductive power of the ring. This conflicted climax is one of the elements that adds power to this story. Typically in a Hollywood film, the hero accomplishes both his physical and emotional goal.

Resolution

The resolution wraps up the story after the climax. The resolution of The Lord of the Rings involves the return to the Shire and ultimately Frodo’s departure with the Elves to a land of peace.

In most stories, the character changes or travels a character arc, a character may start cowardly and by the end prove he is brave, or start the story unsure and by the end be full of confidence. Because Frodo never achieves his emotional goals and because he is so wounded by the evil power of the Ring, he also follows an arc. He travels from a point of carefree, innocence at the beginning to a point of being somber and restrained. Some critics see the journey of Frodo is one from innocence to experience or from childhood to adulthood.

Scenes and Sequences

A narrative is comprised of individual scenes and sequences. A scene is an action that takes place in one location. A sequence is a series of scenes built around one concept or event. In a tightly structured script, each scene has a mini-goal or plot point that sets up and leads us into the next scene, eventually building the sequence. Some scenes and most sequences have a beginning, middle, and end, much like the overall story.

Jeopardy

The characters’ success or failure in achieving their goals has to have serious consequences for them. It is easy for the writer to set up jeopardy if it is a life-and-death situation, such as being butchered by orcs in The Lord of the Rings. It is harder to create this sense of importance with more mundane events. This is accomplished by properly developing the character. In a well written script, if something is important to the character, it will be important to the audience even if it is not a life and death situation.

Point of View

Point of view defines from whose perspective the story is told. The most common point of view (or POV) is third person or omniscient (all knowing). In this case the audience is a fly on the wall and can fit from one location to another, seeing events from many characters’ points of view or from the point of view of the writer of the script. This is the point of view of The Lord of the Rings.

The other major type of point of view is first person or subjective point of view. In this case, the entire story is told from one character’s perspective. The audience sees everything through his or her eyes. The audience can experience only what the character experiences. Used exclusively, this type of point of view has numerous practical problems. The primary one is that we never get to see the lead character’s expressions except in the mirror. Because of this, stories that are told in subjective point-of-view narrative are sometimes told in third-person point of view in terms of the camera. This allows us to see the lead character. Voice-over narration is often used with subjective point of view.

Pace

Pace is the audience’s experience of how quickly the events of the narrative seem to move. Many short sequences, scenes, and bits of dialogue tend to make the pace move quickly; longer elements slow it down. Numerous fast-moving events in a scene also quicken pace. Writers tend to accelerate pace near a climax and slow it down for expositional and romantic scenes. A built-in time limit accelerates pace and increases jeopardy by requiring the protagonist to accomplish his or her task in a certain time frame. In The Lord of the Rings, Frodo had to destroy the Ring before Lord Sauron and his armies amassed the power to destroy all the good folks of Middle Earth.

CONCLUSION

The above has only scratched the surface of a complex topic, but it should be an adequate foundation for the multimedia narrative discussion that follows. A key issue we will be looking at is how the writing of multimedia narrative differs from writing linear narrative.

REFERENCES

Conners, A. Telephone interviews with the author, December 1995, October 1999, January 2006.

Costello, M. Phone interview with the author, July 1999, February 2006.

Field, S. (1982). Screenplay. New York: Dell Publishing.

Riordan, D. Telephone interviews with the author, June 1994, October 1995, December 1995, January 2006.