Retire.

Few words in the English language carry as much weight as this one.

In a baseball game, if a pitcher retires the side quickly, that means he shut the other team down. He’s an ace! On the other hand, if the team retires his jersey, that jersey is no longer worn—it no longer functions. They hang it up in the rafters, or in a musty locker room that smells of sweat and dirty socks.

Even when I was young, I remember thinking retirement was a good thing. As far as I could tell, retirement meant you could just stop working, and that was good, right?

Or is it? When our heart stops working, we die. So what happens when we stop working?

Over time, as I’ve thought about this more, I’ve realized it’s not really that we want to retire. It’s that we want to be in the position to retire. There’s a big difference. We don’t want to stop working, but we do want to stop working with our annoying boss, or our lazy coworkers, pushy vendors, expensive lawyers, or demanding clients. We don’t really want to stop everything and make shuffleboard or mah-jongg the highlight of the day. We just want to be in the financial position to not have to grind it out at a job we no longer love, or maybe never loved.

We want the option. We want the freedom. This is America!

As our economy has taken its lumps over the past decade, I’ve gotten the sense that more and more Americans view a happy retirement as an elusive or even unattainable goal. So they work harder, logging more hours and losing more sleep, striving tirelessly toward the notion of a happy retirement. Their logic is simple: work more, save more, be happier. Makes sense, right?

Wrong. It doesn’t always work that way.

Today the paradigm has shifted. It’s not always about working longer or harder; it’s about making smart choices with your money and your life. Some of the old strategies still work, others don’t—and you have to know what to keep and what to discard.

I’m here to tell you: you can create your own definition of retirement—and you can do it sooner than you think. I don’t just want you to retire. I want you to retire happy. And now you can.

What Makes a Retiree Happy?

I don’t claim to be a doctor of happiness, but I do claim to have done my research. In my comprehensive survey of more than 1,350 retirees across 46 states, I was ruthless in my quest for answers. I asked retirees the questions no one else was asking. Sure, I asked about net worth and income, total assets and home value. But I asked them other questions, too, about their overall quality of life.

First, I asked them: How happy would you rate yourself on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 is not happy and 5 is extremely happy? Then I invited them to tell me about their lives. Where did they shop? What kind of cars did they drive? How many vacations did they take each year? Were they married or divorced? Did they have children? If so, how many? What activities and interests did they pursue? How would they define their purpose in life?

Once the data was crunched, I went to the Georgia Tech Department of Mathematics and had the data’s “confidence and significance” verified by the former president of the GA Tech Math Club, along with one of her former math professors. I used the data to create a series of graphs and charts, which you’ll see throughout this book.

The more I looked at the survey data, the more things I found that surprised me. Happy retirees hate fast food and love steak. They avoid cheap chains but don’t overindulge either—Ruth’s Chris Steak House and Olive Garden rank among their favorite restaurants. They shop at Macy’s and Kohl’s. They don’t drive BMWs, though unhappy retirees often do.

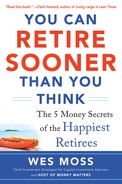

Happy retirees have busy social schedules. They play sports and volunteer, whereas unhappy retirees tend to prefer hunting and reading. They have at least two kids, and three seems to be the magic number. The happy folks have at least 3.5 core pursuits—the activities and interests they love to do. (More on core pursuits in Chapter 4.) And lest you think retirees are homebodies: take a look at Illustration 1.1. Happy retirees average 2.4 annual vacations, while retirees in the unhappy group take only 1.4. One vacation may not seem like a big deal, but it can mean the difference between being happy and being miserable.

Illustration 1.1 Average Number of Vacations per Year

Once a year, happy retirees are out rock-climbing in the Grand Canyon or swimming with sharks in Aruba, while their unhappy friends are stuck at home, reading.

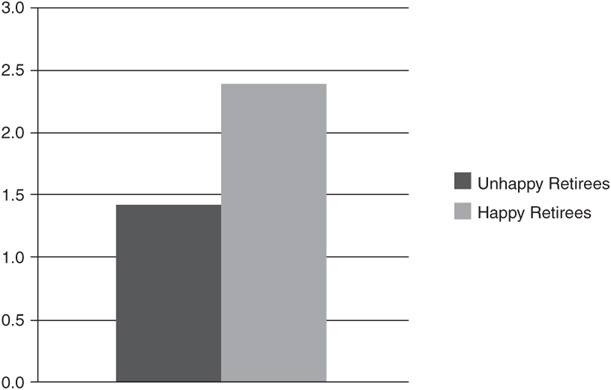

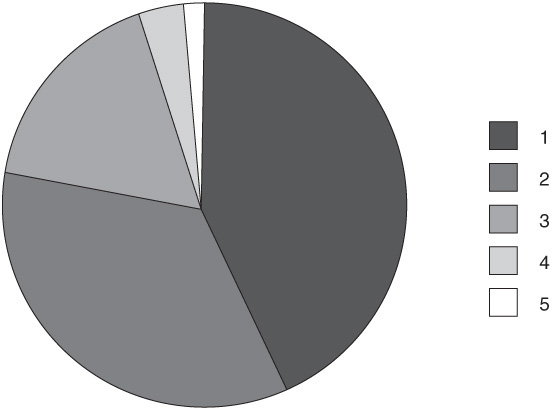

In addition to the fun stuff, I pinpointed certain financial signifiers that showed up repeatedly among the happy retirees. They lived in homes with a value of at least $300,000. They didn’t have a mortgage; if they did, their payoff was in sight. They had a liquid net worth of at least $500,000, and they spent at least five hours per year planning for retirement, usually more. They also had at least two or three different sources of income in retirement, including social security, pension income, income from investments, income from rental properties, part-time work, and government benefits (Illustrations 1.2 and 1.3). In Chapter 7, we’ll go into more depth on how having diverse sources of income can lead to greater happiness.

Illustration 1.2 Happy Retirees’ Number of Income Sources

Illustration 1.3 Unhappy Retirees’ number of Income Sources

The vast majority of happy retirees have two or three income sources, while the majority of unhappy retirees have one or two.

Have you noticed one theme that keeps repeating itself? Overall, the happiest retirees live in the “middle.” When it comes to home values, vacations, restaurants, cars, and shopping, happy retirees have found the sweet spot in the middle. Nothing low-rent, but not high-end either. They’re not spending lavishly—but they’re also not depriving themselves. They’ve struck the balance that’s right for them.

I’d like to help you strike the balance that’s right for you.

On the 1-to-5 happiness scale, I want to see you at a 4 or 5. I want money to facilitate that happiness, not create it. Start thinking of money as a way to support being happy, rather than manufacture it. If you can make that subtle shift, you’re well on your way.

In the following pages, I’ll introduce you to a number of happy retirees who have applied these principles with great success. I don’t have to look far for people in the happy group—my client base is chock-full of them. These are people who, for the most part, have done things right. They’re not all millionaires and multimillionaires, but they have made smart choices with their money and are able to reap the benefits.

I’ll also introduce you to some of the families I work with who haven’t retired yet. These are men and women in their thirties, forties, and fifties who are making smart decisions now that will pay off later. Take, for example, Nick and Katie Benjamin.

The Benjamins Will Retire Sooner than You Think

Nick and Katie are one of my favorite couples. Both come from parents whose retirements were completely crushed by their respective companies. Both vowed never to let that happen to them.

Katie’s dad worked for Chicago Bridge & Iron. They laid him off a year prior to his full pension eligibility, so his pension got whacked down to 20 cents on the dollar. He didn’t really have a 401(k) because that just wasn’t a standard benefit during his era. In other words, he got a bum deal.

That means Katie felt the financial brunt as well. A lot of kids have to move back in with their parents early in adulthood, but it’s not usually because the parents need financial help. In this case, Katie’s parents needed her to pay rent in order to stay solvent on their mortgage!

Nick’s dad worked for Eastern Air Lines, a big airline in Atlanta that went out of business in 1991. It took him a long time to find work again. Like Katie’s dad, his pension got severely hit and he ended up with miniscule savings. Now, both of their parents are in their seventies and barely scraping by. Nick and Katie are going to have to help support them.

It’s easy to see the genesis of a mentality that has taken hold in Nick and Katie. It’s been apparent to me ever since they started working with me a decade ago. Their determination set them on a course of making razor-sharp financial decisions. It kept them from sinking money into a house they couldn’t afford or cars they shouldn’t drive. If they stay on course, Nick and Katie may be able to retire in their midfifties. Do I have your attention yet? Good.

Nick and Katie both work, and they each make around $150,000 to $175,000 a year. Not a bad chunk of change, especially in Atlanta. But they haven’t always had this powerful double income—and they’re certainly not one of the much-discussed “1 percent,” which in 2011 required a minimum household income of $516,633. For many of their first years of marriage, they were both averaging around $75,000 a year, both as consultants in the technology industry. So despite their new relatively high double income, Nick still drives a 1995 Nissan Maxima with 200,000 miles on it. Katie drives a 1998 Nissan Maxima with 300,000 miles on it. They do have a used 2001 S-Class Mercedes, which is pretty nice but reasonable.

They aren’t on financial lockdown, either. They aren’t total stiffs. I wouldn’t be writing about them if they were. They go out to dinner, they eat what they want, and don’t have to worry about the little stuff because they know they are nailing it on the big fundamentals. Because they are pound-wise, they can afford to be penny-foolish at times.

The most important big-ticket item is their housing situation, and it almost didn’t go in the right direction. Like many, Nick and Katie were at a crossroads and nearly took the wrong turn. They made a deposit on an expensive house that would’ve basically depressed them financially—for years if not decades. Everyone else was doing it. Why not them?

But then they thought long and hard about what they were doing. Taking a small penalty, they decided to get their deposit back on the house and instead live in a two-bedroom apartment for the next two to three years. They took that deposit ($30,000) and used it to pay down student debt.

That gave them the momentum to continue making smart choices. They began to live by a rule of maxing out their 401(k)s every year, no matter what. Though they were both bringing in salaries, they decided to live on just one salary—the lower of the two. They had vacation time, but kept it regional, often opting for the “staycation” to avoid huge out-of-pocket costs.

When I met Nick and Katie in 2004, right after I finished my run on NBC’s The Apprentice, they were 34 and 32 years of age, respectively. They had $50,000 total in savings. Today they have over $450,000 in retirement assets saved. They own their own home, on which they owe less than $200,000 of its $250,000 value, and it will be paid off by the time Nick is 50 years old.

That’s not all. They own seven single ranch home rental properties, all in the $100,000 to $150,000 range. Sure, they made a few mistakes along the way, such as buying a couple of houses right before the housing bubble burst in 2007. However, they learned from those mistakes. They were able to do some financing through a government program called HARP 2, which essentially gave them a way to refinance and get better interest rates even on some of their properties that were “underwater” (properties that were worth less than they owed). Submarine financing, if you will.

Nick and Katie lowered their interest rates, which stopped the bleeding that was their $1,800 a month of net negative cash flow. From there, they began to break even, and they then bought a couple of other smaller places in 2009 and 2010 that finally provided a positive cash flow.

The Benjamins will have their mortgage paid off by age 50, and they’ll be able to do the things they want to do. They’ll have a real purpose behind their money. Katie will work part-time in real estate without any pressure. She’ll teach spin classes rather than just going to the gym. Nick will play more golf. They will travel more. They are currently pregnant, having decided to have a child later in life. Since my studies have shown that the more kids you have (up to three), the happier you are, this was music to my ears.

Nick and Katie lived and still live slightly below their means, which is key. We all know how to do it, but we get caught with our hands in the consumer cookie jar. Ever since the days of “Mad Men” in the 1950s, marketing campaigns in America have been extremely adept at convincing Americans to buy whatever they want to buy. Madison Avenue has made us feel financially invincible.

We aren’t.

But if we live like the Benjamins, we don’t have to be. With judicious decisions and hard work, you too can retire early. You don’t need $5 million to do it. You may not even need $1 million. The Benjamins have less than half of that (though they’re well on their way to having a good deal more). Thanks to their singular focus and smart financial choices, they’re on track to retiring a lot sooner than their friends and coworkers.

Wouldn’t you like that to be you?