Steve Burton is a high-powered senior vice president at a big Fortune 100 media company. You know the type—a motivated executive with a large, steady stream of income that continues to help fill his savings reservoir. Steve has worked since he was 16, and he’s done well for himself. He’ll be able to retire early, not simply because of his high income, but because he’s been a prodigious saver and is taking the necessary steps to be a member of the happy group.

For the last three years, Steve has been training to become certified in timepiece creation and repair. From the Rolex to the Bulova to all the other intricately designed time-telling devices, he’s on his way toward a three-year watch specialist certification. It’s actually called a CMW21 (Certified Master Watchmaker of the 21st Century), a fascinating designation I would have never known about if not for Steve. It’s amazing the things I continue to learn and be exposed to thanks to happy retirees.

But back to Steve. This executive loves watches. Picture Warren Buffett hunched over your mom’s Timex, an old but proud sign above his desk that reads, “It took a licking, but I’ll get it ticking.” It doesn’t matter that Steve works in a big fancy office and makes a lot of money. He loves the intricacies, the design, and the systematic genius of watches.

It’s become a core pursuit for him. And guess what? It’s part-time work. Once he retires from the stressful, high-powered job that’s allowed him to accumulate 3.5 million Delta SkyMiles, he’ll be ready to start cranking on the watches—no pun intended.

Steve will probably retire around 56 or 57 and work on watches three to four days a week—at his own leisure. He’ll make a decent living doing it, probably anywhere from $50,000 to $80,000 per year, to supplement the other financial steps he’s already taken to plan his retirement. All the more important: he’ll have fun doing it. Imagine that!

What Steve knows—and many others don’t—is that the more “rivers” or “streams” of income you have, the happier you’ll be. You need to start thinking about this now. Make “multiple streams of income” a mantra and repeat it often.

As usual, the proof is in the data:

• Eighty-five percent of happy retirees have more than one source of income.

• Nearly half of happy retirees have three income sources or more.

• Fifty-seven percent of unhappy retirees report only one source of income.

• The average number of income sources for happy retirees is 2.6.

• The average number of income sources for unhappy retirees is 1.85.

More rivers or streams of income equal happier retirees. It’s that simple. In this chapter, we’ll discuss how to go about making those rivers flow.

The More Rivers of Money, the Greater Your Reservoir

When it comes to generating income, you want to create as many tributaries as possible to come together in one new, predictable larger stream.

For example: A 63-year-old couple may have access to the following:

• Two monthly checks that come from social security (one for $1,750, one for $1,150)

• One small pension from a past employer for $560/month

• One part-time income from Home Depot for $1,100/month

• Investment income from a portfolio of $1,600/month

That’s a total of five different income sources that, in aggregate, equate $6,160 a month—or approximately $73,920 a year (pretax). None of these tributaries are enormous in their own right, but together they create a powerful cash flow of over $70,000 a year.

If money were water, would you think of it as a river or a lake? More often than not, I find the answer to this question is different for men than it is for women. A higher percentage of women look at money—savings, investments, income—as a lake. It’s a giant mass that has been created through previous actions. Men seem to think of it as a river—a more fluid entity that continues to flow and change.

Which mentality is the right one to have? They both are. Remember the following: Money is a river while you’re working and a reservoir once you retire.

Let me explain. While you’re working, you have one or two big paychecks flowing into a reservoir of “savings.” Not all of the money from these paychecks makes it into the reservoir because you need some of it to live, but every year you try to let in as much as you can. The hope is that when you’re 55, 60, or 65, you’ll have filled the reservoir up high enough to provide much of the drinking water you’ll need for the rest of your life.

If you retire from your full-time job, “Paycheck Rio Grande” stops flowing. Most likely your reservoir isn’t full enough to keep you hydrated by itself, so you have to figure out a way to begin collecting water from other sources. This is a big transition—both in thinking and in practice—and your willingness to make this transition is a key factor in your ability to become a happy retiree.

Moving Out of the Accumulation Phase and Into Distribution

The dynamics of money and income shift dramatically throughout our lifetimes. Most of our working years are part of the accumulation phase. We accumulate and expand our wealth in the attempt to “sock” money away for retirement.

We expect our money to grow, and that growth comes through appreciation and income generation. If we have mutual funds that pay dividends, those dividends (aka “income”) are reinvested and continue to grow and accumulate over time (aka “appreciation”). We’re in the accumulation phase from the day we start saving to the day we stop working: in other words, the day we stop receiving our paycheck (or “traditional means” of income)—W-2, 1099, ownership distributions, salaries, bonuses, commissions, fees, etc. So, we have this income flowing in while we’re 30, 40, and 50, but it’s really a source to facilitate our current lifestyle, and a resource to save for our future lifestyle.

But something drastic happens when we hit retirement. That consistent stream of money stops. In some cases it stops abruptly; in cases where one spouse keeps working longer than the other, it slows to a halt. The point is that in a very short period of time, your traditional income stops. The accumulation has been flowing like a giant river, but now the water has dried up.

Don’t panic. We’re going to stop thinking about a giant river and start focusing on ways to create multiple smaller tributaries.

This transition is dramatic, and there are few things that provoke as much anxiety as moving from one big river into several smaller streams. Many people began working in their teenage years and have lived most of their lives generating a steady paycheck. Whether they worked for a company or for themselves, they’ve been generating wage income as long as they can remember—and it can be scary to break that habit.

“I work and therefore money comes in” is the mentality. Now, in retirement, the strategy changes. Rather than grinding it out at the office, you’re relying on a variety of other factors to work in your favor. You’re moving out of accumulation and into distribution. You have to relinquish some control, but if you’ve prepared, that’s not going to be a problem.

Assuming your typical W-2 or 1099 paycheck is no longer flowing, here are some potential sources of income.

• Part-time work

• Social security

• Pension income (state, federal, nonprofit, corporate)

• Investment income

Now let’s look at each of these in detail.

Part-Time Work

Atlanta is the Home Depot headquarters of the world. I see many people, both men and women, who are ready to retire from their full-time career but decide they’d like to go work at Home Depot two to three days a week. Some of them are good at fixing stuff, and some love the garden section. For both groups, working part-time at Home Depot adds to their quality of life and brings in a relatively modest stream of income.

Home Depot is only one option. If the idea of part-time work appeals to you, consider the following:

• If you like retail, fill out at an application at Nordstrom, Ann Taylor, or another clothing store at a nearby mall.

• If you’re into cars, think about applying at Advanced Auto Parts or Pep Boys.

• If sports are your thing, try a sporting goods store like Dick’s or Sports Authority.

• If you enjoy books, apply to work at Barnes & Noble or a local bookstore.

• If you want something high-energy, try Starbucks or your favorite coffee shop.

• If you love your church or temple, see if there’s a part-time position available at your place of worship.

The options really are endless!

Some people take on part-time consulting gigs. What better way to make money and stay engaged and active then to continue being paid for some of the same things you were so good at before you retired?

Recently I’ve been working with Elaine Hill, a woman who was “downsized” from IBM and effectively forced to take early retirement at 59. IBM had been paying her a low to mid six-figure salary—in the ballpark of $130,000 per year. It was a good living but certainly “midrange” for IBM standards. Yet, because of all the benefits that went along with the position, Elaine was considered a “high-cost employee.”

As we all know, every so often companies go in and clean out the “high-cost” employees when the budget calls for it. Unfortunately for Elaine, she was the collateral damage of IBM’s spring-cleaning. On the upside, she barely had time to pour a second glass of chardonnay before IBM asked her to come back as an independent contractor. Essentially, they offered her the old job back, making an income sans benefits.

Elaine’s situation isn’t an uncommon one. Many retirees have the option to still bring in a supplemental paycheck once their main career comes to an end. It’s less tax efficient, less secure, and includes fewer benefits, but that’s okay. Remember: think many small streams, not one big river.

Social Security

Nearly all Americans (if you paid in during your working years) will receive social security payments at some point in their lives. According to the official website, 9 out of 10 individuals 65 and older receive social security benefits.1

The unfunded liabilities of the program are no secret—more money is promised to go out than the government has saved in the social security trust fund.

However, social security is not to be scoffed at in terms of your retirement planning. Even with potential changes on the horizon, it is one of the streams you want flowing into your reservoir. I have clients who get as little as $800 a month and others who receive more than $3,000 a month.

The great part about social security is that once it begins, you can rely on the numbers to generally stay about the same, with very modest increases tied to inflation. And whatever the amount, it’s still another stream. Remember: every income stream matters, no matter how small. The key to money secret #4 is adding as many as you possibly can.

Pension Income

If you have a pension, congratulations! Many of us don’t, including me. Pensions have both a wonderful and tragic history in this country. Is it a legal obligation for your company to pay the pension it has promised you? Yes, but what if the company goes out of business?

I agree with Roger Lowenstein, who wrote about this topic in a 2013 Barron’s article, in which he stated the tendency of companies to neglect the obligation to keep pension funds solvent “is a pity because, when properly run, pensions remain the best form of retirement plan. They do away with many of the risks born by individuals alone, such as outliving one’s savings or retiring at the wrong time.”2 Not to mention, he points out, most people don’t have enough expertise or time to manage their own portfolios successfully.

Yes, it’s unsettling, but luckily we have the Pension Benefit Guarantee Corporation (PBGC), a U.S. government agency that protects the retirement incomes of more than 40 million American workers in more than 26,000 private-sector defined benefit pension plans. The maximum pension benefit guaranteed by the PBGC is set by law and adjusted yearly. For plans that end in 2013, the maximum guarantee for workers who retire at age 65 is $57,477.24.3

In addition to that worry is the fact that one of the most well-documented issues in corporate America is the lack of funding of current pension obligations. There are plenty of examples of this. The same Barron’s article points out instances from Studebaker to General Motors to the State of Illinois to the city of San Bernardino, California. It seems the overpromise and underdelivery of pensions is almost more of an American pastime than the game of baseball.

Not all pension obligations are upside down, but there’s clearly a problem in America: we have underestimated how long people live. Pension programs were put in place decades ago when life expectancies were shorter, and it only stands to reason that with longer life expectancies, those old actuary tables aren’t going to add up.

Despite all this, the chances that a pension will change or default are actually very low (not to mention a backstop from the PBGC). So if you have a pension, it’s wonderfully useful and reliable, and we will gladly let it flow into that reservoir.

Rental Income

There are two approaches you can take with rental income.

1. Wait for retirement and then use a portion of your nest egg to invest in income-oriented properties.

2. Become an accumulator of rental real estate over time.

I saw a lot of individual investors use the first approach successfully in 2009 and 2010, when real estate prices were depressed. Home prices came down close to 30 percent over a three- or four-year period. Rental demand increased as fewer and fewer people were willing to take on mortgages, so it became financially productive and logical to buy a house for $100,000—if you could generate a monthly rent of at least $833 from it, equaling 10 percent per year on your money.

Does this interest you? Great. Below is a quick-and-easy how-to. You can do either of the following:

• Buy a house for $100,000—in cash, so there’s no mortgage payment—generating approximately $10,000 a year in gross rental income (a 10 percent gross yield on the cash you’ve invested).

• Put some money down (say, 20 percent) and borrow the remaining 80 percent from a bank. As long as you have a reasonable interest rate on the loan, you should still have decidedly positive cash flow from the property.

In both instances, you now have an income-producing property that will pay you monthly cash flow for as long as the house is still standing and you have renters. I have seen countless happy retirees use this methodology and turn a portion of their retirement nest egg into income-producing rental property. (Remember Nick and Katie Benjamin?)

This can be a very effective use for a portion of your retirement nest egg. Not only is it very effective at generating cash flow, it can give you a part-time job managing the properties if you have a few of them. Fixing broken toilets, scheduling air conditioner repairs, patching leaky roofs, making sure the lawn is mowed—all joyous work for those who love to be handy!

Some people really enjoy being a landlord. The Benjamins love it. I work with lots of happy retirees (and aspiring happy retirees) who love it as well. It keeps them busy and keeps another stream of income trickling into the reservoir. Furthermore, it helps solve for the strange, listless no-man’s-land some retirees experience when they go abruptly from full-time work to having nothing to do and no income to earn.

The second approach to rental income—and the better way to do it in my opinion—is to become an accumulator of rental real estate over time. The sooner in your life you start accumulating property that generates monthly rental income, the more significant it will be by the time you get to that age of financial independence.

Robert Kiyosaki’s New York Times bestselling book Rich Dad, Poor Dad puts a big focus on rental income. It was really popular in the decade of the 2000s because at that time real estate paid a nice income, and nearly all types of property steadily rose year after year in value. A lot of leverage was involved (meaning borrowed money) but it didn’t matter at the time because the real estate market was doing so well. If someone wanted to buy a million dollars’ worth of property, he could put down $100,000, borrow the other $900,000, and get all his rental property working for him, paying him a nice 5 to 10 percent in income.

Furthermore, all of the asset values were going up because all of the real estate prices were going up and up and up. Everything was great—until the financial crisis of 2007, 2008, and 2009 hit.

This was the first time in our generation that we saw real estate prices go down, and I don’t mean by small figures. Prices fell between 25 to 65 percent, depending on where you lived. Condos that were bought on spec in Nevada and Miami were down 50 to 70 percent.

[Note: Now that we’ve come through, to some extent, and arrived at the other side of the financial crisis, real estate prices have clearly stabilized. In fact, at the time of writing this book, home values across most of America have been on the rise for the better part of two years and are now comparable to home values in 2004. So, home prices have a long way to go to get back to the levels we saw in 2006–2007, but an environment of flat to slightly higher home prices (like we may be in for the next several years) makes favorable conditions for property owners and landlords alike.]

So taking the earlier example: if I buy a house for $100,000 and get a renter to pay $833 per month, that comes out to exactly $10,000 a year. That’s a nice 10 percent (gross yield) if I actually paid cash for it. (Yes, the net yield will be lower once I pay for maintenance and taxes and upkeep on the house.)

But if I get a loan from a bank, I’m only putting down $10,000 out-of-pocket and I’m getting $10,000 a year in income. I’m actually getting 100 percent return on the actual cash that was outlaid because the bank is fronting the money. In other words, I’m getting a 100 percent return on my “cash-in.”

That’s why rental real estate can be such a great option—as long as market prices don’t go down dramatically. Even if the market stays stable, without going up, it’s a great way to make money. I’m only putting 10 percent of my own money “in” and I’m getting 10 percent “out” (of the home’s total value). That equates to a 100 percent return on my actual cash invested. Where else can you get that? Nowhere. The only way you can do it is if you’re able to borrow the money—that’s the definition of leverage. If the investment goes well, it’s a very positive scenario.

However, if the investment doesn’t go well, that’s when the leverage works and compounds against you, like we saw with Lehman Brothers in 2007. They had borrowed (were leveraged) 45 more times than they actually had in cash.

This is the riskier part of the second approach to rental income. If you become overleveraged, small price fluctuations in your underlying assets (property prices) can mean huge divergences in your financial statement and balance sheet. That’s exactly what happened to a large portion of the country, as we found out when the financial crisis hit.

Not even the highly wealthy are immune. Let’s say a high-powered mogul named Tanner Schmidt III borrowed $1 billion to buy a swanky Manhattan skyscraper. If the value of that building decreased by just 5 percent, all of a sudden Tanner’s net worth changed by $50 million in an instant. Pretty soon we’re talking real money, right? Tanner just choked on his monocle. (Don’t worry, Tanner—this was just a hypothetical.)

I only point out the risk to make you aware. Borrowing money is still a great way to buy the right real estate and generate rental income—as long as you don’t overextend yourself. Make sure you only leverage what you can handle and not a penny more.

What do I mean by “only leverage what you can handle”? For retirees, imagine all of your real estate loans were called at once. Sure, you could sell properties (hopefully in a timely manner) and pay the loans off. But what if you could not? Think about the financial situation that would put you in. All of a sudden banks are demanding their money back, essentially “calling your loan.” If you don’t have the liquid resources to do so, and if your properties are illiquid, you can quickly become insolvent. So, keep this in mind before you take on too much leverage or debt.

Investment Income

In its simplest form, investment income is a combination of the income-generating power of all your accumulated assets—cash, stocks, bonds, mutual funds, exchange traded funds (ETFs), REITs, closed-end funds, master limited partnership stocks (MLPs), energy royalty trusts, etc.

Here’s the thing you need to know: that combination of assets has to grow over time so that one day, when you stop adding to it, it will do the work for you, generating enough income to supplement all of the other areas that I just described. So how do you put yourself into a position where it can? You spend much of your life building this lump sum by diverting and saving assets in your retirement reservoir; now it is vitally important that those assets use their own momentum to generate both growth (appreciation) and income (cash flow).

While you’re working, you should be accumulating wealth inside of your:

• 401(k)

• 403(b)

• 457 plans

• Roth IRAs

• Regular IRAs

• Investment accounts

• Savings accounts

Those are the multiple places you’re going to put your money in order to build the aforementioned reservoir. Now let’s talk about “growth” versus “income” when it comes to how your savings can grow.

People are very used to thinking about investment money in terms of growth, and that’s a good thing. The reservoir needs to get bigger. I want to buy stock at $10, and I want it to go up to $11 and then $12, and then eventually up to $20 and beyond. That is the definition of what’s called “capital appreciation”—also known as “growth investing.”

“But Wes,” you might be thinking. “Is there any other way?” Funny you should ask. There are hundreds of different ways to invest, but they all center around the growth of your capital.

Take, for example, an income-oriented approach. Let’s say you buy stock for $10, and each year that stock pays a $1 dividend. Over the course of 10 years, you end up with $20. Your original share price didn’t change—it stayed at $10—but the company paid a $1 dividend to you each year. (See Illustration 7.1.) You end up with the same amount as you would if, rather than paying a dividend, the stock price grew to $20 per share.

Illustration 7.1 Turning $10 into $20 Using Two Very Different Approaches

In this example, both all-growth and all-income investing get you to the same result—your $10 has become $20—but you get there in very different ways.

I use this example to explain the difference between income investing and growth investing to my clients and radio show listeners. Take a look at Illustration 7.1.

In the all-growth example, stock ABC goes up by $1 every year for 10 years—and your original $10, grows to $20. In the all-income example, stock XYZ stays totally level for 10 years and pays you $1 per year. So, you are left with $10 in the original XYZ stock price plus $10 in dividends, leaving you with $20. In both cases, you’re left with the exact same amount of money. But you have arrived at the same result in very different ways. That, in essence, describes the difference between growth investing and income investing.

Both methodologies can work, but I believe income investing provides more predictability and consistency when structured correctly. Imagine if every single component of your retirement portfolio (every stock, bond, mutual fund, ETF, etc.) paid you some level of consistent predictable cash flow. Think of 20 or 30 or 40 different components all doing some version of what stock XYZ does in Illustration 7.1.

Where do these 20 to 40 different components come from?

The DID Approach to Income Investing: Dividends, Interest, and Distribution

• Dividends come from stocks—usually large U.S. and international companies and real estate investment trusts or REITs.

• Interest comes from various types of bonds—government, municipal, corporate, high yield, floating rate, treasury inflation protected securities (TIPS), and international bonds.

• Distributions come from a whole host of other areas, including master limited partnerships (MLPs), closed-end funds (CEFs), and energy royalty trusts.

The key to income investing is to have multiple income-producing components all working for you in a harmonious balance. Using the DID approach allows you to have a highly diversified strategy of generating income and a highly diversified way to allocate your investments so that they are not in one basket or bucket. (I will delve deeper into the “bucket approach” to income investing in Chapter 8.)

Quite simply, the areas I described above add up to a cash flow, which is why I want to at least get them on your radar. What they all have in common is that they come to you (or get added to your investment accounts) as new money market funds—essentially cash, as if you had just received a paycheck. When you are in retirement, this cash income is an essential tributary.

At times, the cash flow can be as much as you were used to seeing from your W-2 paycheck. Of course, this depends on the size of the reservoir that you’ve built and your level of percentage yield (aka the level of cash flow that gets produced). One thing I love about this is that you start the year with a portfolio yield—cash flow divided by your overall portfolio value—and the result in actual cash flow is often very predictable. That means at the beginning of each year, if you know your portfolio yield, you will know with a high degree of accuracy how much cash flow your portfolio should generate for the coming year, regardless of how much “markets” go up or down in a given year.

For example: Let’s say I get $5,000 in cash flow on $100,000. That means I’m getting a 5 percent cash flow. That means that my portfolio yield is 5 percent. So, if I start the year out with a 5 percent yield, then that part of my portfolio experience is very predictable. The yield and cash flow should generally be the same for the next year (or more), and there’s a high level of comfort that comes along with that. A portfolio of $100,000 that has a yield, or cash flow, of 5 percent should produce $5,000 in new cash flow—and that’s just the cash flow—regardless of how much the overall portfolio value changes (appreciates or depreciates) in a given year.

• Good market example. $100,000 portfolio with 5% yield = $5,000 in cash flow. But the stock market had a good year, so in addition to collecting your $5,000 in cash, the portfolio value may also end the year higher, at $110,000.

• Bad market example. $100,000 portfolio with a 5% yield = $5,000 in cash flow. But the stock market had a bad year, so in addition to collecting your $5,000 in cash, the portfolio value may also end the year lower, at $90,000. But that’s okay because you’ve collected your $5,000, and you haven’t touched the “principal value” of the portfolio. You have only taken the cash flow and can now wait until the principal value has a chance to rebound in price (which may take time).

The important part to focus on here is separating your portfolio’s cash-producing ability from its overall ability to grow in value over time.

Yes, we want both income and growth—but in any given year only the cash flow part is highly predictable, so it’s the only stream we can count on.

The More Streams of Income, the More Freely Happiness Will Flow

Now that I’ve shown you the various types of income streams you can bring in, let’s talk about their correlation to happiness. Specifically, I want to answer a few very important questions.

• What is the amount of income you need?

• How are you going to get that income?

• Is happiness directly related to the number of income streams?

Let’s first figure out the amount of income you need. Refer to Illustration 7.2.

Illustration 7.2 Happiness by Current Income (Mean)

It probably won’t surprise you to see that higher income equates to more happiness. But look more closely, and you’ll see the plateau effect as happiness levels off.

The mean, or average, income for the happy group falls right around $82,770 per year, whereas the average income for the unhappy group lands at $55,370. What does this reveal? A lot!

More income equals more happiness—but only to a point. The place where the amount of income needed starts to level off shows yet another example of the “plateau effect.” I want you to understand this concept and the average level where it occurs so that you can have an inflection point to shoot for (Illustration 7.3).

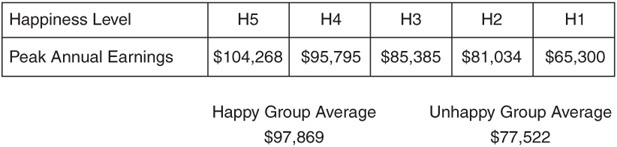

Illustration 7.3 Peak Annual Earnings for Each Happiness Level

This data reflects the “peak income” of people who are within 10 years of retirement or in retirement currently.

Now, for current retirees, what’s the magic number to reach in retirement income? I’m looking for an inflection point: the exact point where people begin to jump from “not” and “slightly” happy to “moderately,” “very,” and “extremely” happy. When I tabulate the data from these graphs, I get $72,277.

1. Assuming a 20 percent tax rate, let’s multiply $72,277 by 0.8, which gives us $57,281 per year.

2. Divide that by 12 months, which gives us $4,818 per month. In other words, to reach a sense of moderate happiness, the average retiree needs to have close to $5,000 of spending money per month.

My survey data tell me that a meager 15 percent of the happy group have only one income source. We can deduce it’s pretty hard to achieve happiness with only one source, right? You need more than that, obviously—but how many more?

Thirty-five percent of happy retirees have two income sources and 32 percent have three, but there’s a steep drop-off with four income sources—it falls all the way to 11 percent. That tells us it’s pretty tough to have four income sources. Still, if you can do it, go for it. You’re livin’ the dream.

If we look at the big picture here, we come up with one key point. The more (and different) income sources you can rely on in retirement, the more income stream diversification you will have. That leads to a higher sense of safety, security, and the cushion that is so important to our sense of well-being and happiness.

The Most Common Income Streams for the Happiest Retirees

What were the most common sources streaming toward the reservoir? Social security was the number one answer. Some retirees had social security and disability. Some had social security and a pension. Some had social security and investment income.

If you look at the moderately happy to extremely happy group, there are some interesting conclusions. The diversification of streams was higher for this group, which wasn’t surprising.

The extremely happy group mostly listed pensions first as their primary source, then dividend income after that. They also listed part-time work mixed with social security. Some other source combinations that came up were corporate pensions, teacher retirement pensions, social security, rental, and portfolio income. These people know how to diversify—and I love it!

These are the income streams many of the happiest people were receiving. I want you to see why it makes so much sense, because I want you to be just as happy as they are. I want you to focus on the importance of diversifying the money you live on. Ideally, I want you to start this at an early age, but the important thing is to start now. I know you can do it because you’re smart enough to be reading this book.

No One Is Perfect—Plan and Diversify Accordingly

There is no one perfect source of income. Even if you own a $20 million building free and clear that pays you a clean $1 million per year in net cash flow, it could be taken down by an earthquake (worst-case scenario). I’m exaggerating merely to show the importance of diversifying your sources so you can keep standing if one of them takes a hit.

For the Gen X- and Gen Yers reading this book, there’s a good chance your social security benefits will be reduced by the time you reach retirement. Don’t sulk. It’s the way it is, and you need to adapt by having an even higher income. You also need to sharpen your focus on creating your own income sources.

If you are a proud member of Gen X (the generation born after the baby boom, between the 1960s and the early 1980s) or a millennial (birth dates in the mid to late 1980s and onward), you need to save even more than your parents and grandparents did. Raise the walls of that reservoir so more water can flow in and you can generate more income through income investments.

Put a greater weight on a 401(k), 403(b), or 457 plan, depending on your specific situation. As a millennial, there will most likely be less financial support from your company and government in your retirement years by the time you get there.

It’s not your parents’ or grandparents’ fault. Don’t blame them. The system was built for a certain life expectancy and, put simply, people are living longer today than they used to. If the social security and pension architects had known the generation after my grandfather, who worked at DuPont until he was 64 and died at 74, was going to be full of people living until 85, they would’ve calculated for it and made the monthly pension payouts smaller.

Be glad your grandpappy and nana are still alive! Extra years of life for your loved ones are a positive thing, and worth the cost of having a little less extra money coming in from some Fortune 500 company. Sure, more of the onus is on you to provide for yourself, but that’s okay because you’re reading this book. You’re smart and resourceful. You’re the future. You’ll be able to retire sooner than you think!

I want you to find comfort as you head toward retirement, and one way to do that is by observing money secret #4: combining several different tributaries to form one significant income stream. Develop an income stream of three or four sources, not just one, and put yourself in the position to retire happy. Before long, you’ll be floating on top of your own financial reservoir, mai tai in hand, without a care in the world.