Chapter 5. Gettin’ Your Glass On: The lowdown on lenses

Captured with a point-and-shoot camera on the edge of the Sahara Desert, this shot’s wide angle helps convey the vastness of the sand dune.

Telephoto or wide? Zoom or prime? What about macro? What does it all mean, and who really cares?

For a lot of people, making the decision about what camera to buy is tough enough, but choosing a lens to go with it? Sheesh. Because they’re treading in unfamiliar territory, people often find themselves at the mercy of whichever salesperson is around, possibly leaving the store with little to no understanding of what they just bought, how to use it, or if it’s really what they were looking for. As it turns out, the lens you choose (or that comes built into the camera you buy) plays a more integral role in the look, feel, and quality of your images than the actual camera body itself does.

Wait—what? That’s worth repeating. The lens you choose can actually be more important than the camera body itself. It sounds crazy, doesn’t it? But it’s true—and learning what to look for in a lens (and what all those numbers on it mean) will serve you well. That way, you’ll understand what it is that you already have and can dream about what you might want to get the next time you’re in a camera store.

Tip

If you have a point-and-shoot camera and you’re thinking, “Lenses? This doesn’t apply to me... mine is built in,” you’re only half right. Be sure to check out the special section just for you at the end of this chapter.

What’s with all those numbers?

When you look closely at a lens, there’s a fair amount of numbers printed on either the front of the lens itself (Figure 5.1) or somewhere around the rim (Figure 5.2)—and though it may seem like a bunch of mumbo jumbo, it’s actually pretty important info and can tell you a lot about the lens and what it’s capable of.

Figure 5.1. Lens information is generally found around the front of built-in lenses.

Figure 5.2. Interchangeable lenses usually feature the lens information around the rim.

Focal Length

The first number, or set of numbers, you see on your lens refers to its “focal length,” measured in millimeters (mm). Roughly translated, focal length relates to how close up or far away objects will appear when viewed through the lens. Essentially, the bigger the number, the more up close subjects will appear, and the smaller the number, the farther away things will appear.

To give you a better idea of how this all plays out in real life, look at Figures 5.3–5.7 and note the various focal lengths used to create each image. Photographed from the same position, the only difference between each shot is the focal length.

Figure 5.3. Captured with an extremely wide focal length of 16mm, the scene appears very far away.

Figure 5.4. Shot at a focal length of 35mm, from the same position, the scene appears closer than before.

Figure 5.5. A focal length of 50mm brings the scene even closer.

Figure 5.6. The scene appears slightly closer again with a focal length of 70mm.

Figure 5.7. The same scene, captured with a telephoto focal length of 200mm, appears dramatically closer than before.

Lenses with focal ranges of 35mm or smaller are generally considered “wide,” and lenses with focal lengths of 85mm or more are often referred to as “telephoto.” A lens around 50mm is roughly close to the way we see things with our eyes and is generally considered neither wide nor telephoto. It is often referred to as “normal” or “standard.”

A single number, such as 24mm, represents what’s known as a prime or fixed lens, meaning that it’s not capable of zooming. Such a lens is designed and optimized for only a single focal length—in this case, 24mm.

Tip

The numbers on a point-and-shoot lens mean the same thing, but the scale is radically different, so don’t panic if your lens indicates a focal length range of 6–22.5mm (the equivalent of roughly 28–105mm).

A range of numbers, expressed with a dash such as 70–200mm, indicates a zoom lens, capable of different focal lengths—in this case ranging from 70mm to 200mm.

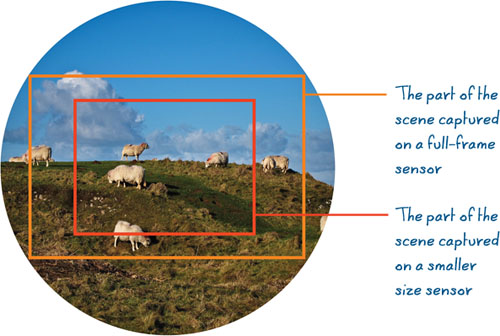

The bottom line? Depending on your camera body, you may be able to get the close-up shots you’ve always dreamed of without having to pay for a super telephoto lens. In some cases, your 200mm lens might behave like a 300mm lens. Now that’s some serious bang for your buck!

Of course, if your camera has a smaller sensor and you like to shoot at a lot of wider angles, the opposite would also be true. The 24mm lens you loved at the camera shop might behave like a 36mm lens on your camera body, meaning you’d need an ultra-wide lens to get a standard wide-angle shot.

To determine your camera body’s crop factor, you’ll have to read some of the techno babble in your user guide or jump online and look it up. Crop factor is typically listed among all the other tech specs related to your camera and usually has a value of something like 1.3, 1.5, or 1.6.

For the sake of example, let’s say your camera’s sensor has a crop factor of 1.5, and you’re curious how a 50mm lens would behave on it. To figure it out, take 50 (the focal length of the lens in question), multiply it by 1.5 (your camera’s crop factor), and you get 75. Thus, on your particular camera, a standard 50mm lens would behave like a 75mm lens.

It’s worth pointing out that some lenses are made specifically for cameras with smaller-sized sensors and have focal lengths that have already been converted. When in doubt, read the specifications or ask a knowledgeable salesperson.

Maximum Aperture

In Chapter 1, we talked about aperture and the role it plays in creating an exposure (keeping in mind that aperture is a function of the lens itself, not the camera body). Similar to the pupil of your eye, the aperture can dilate or constrict, letting in varying amounts of light and affecting the depth of field.

Appearing on your lens right next to the focal length, you will find a numerical expression representing the maximum (largest) aperture opening that particular lens is capable of, usually expressed as “1:” followed by the maximum aperture. For example, a lens described as a 24mm 1:2.8 would be a fixed lens with a focal length of 24mm, whose largest aperture setting is f/2.8. The lens is still capable of smaller apertures (like f/11), but the largest it would be capable of is f/2.8.

If you’ve spent time shopping for lenses, you may have noticed that a lot of zoom lenses feature not a single maximum aperture but, rather, an aperture range. If you have a lens that says 24–150mm 1:3.5–5.6, it means the lens is a zoom lens with focal lengths ranging from 24–150mm, whose maximum aperture varies depending on where you are within the zoom.

Depending on where you are within the zoom? What in the world does that mean? For example, if you’re zoomed all the way out wide to 24mm, you could achieve a maximum aperture of f/3.5. But once you zoom in, you lose the ability to open up your aperture all the way to f/3.5 as before and can then only open to f/5.6.

Lenses with larger maximum apertures (generally 2.8 or larger) are often referred to as being “fast” because the larger apertures allow more light to reach the camera sensor, letting you shoot with faster shutter speeds in low-light situations where you might otherwise need a tripod. (Remember, larger apertures are actually smaller numbers; thus, f/2.8 is a larger aperture than f/8.)

Tip

As you saw in Chapter 2, many point-and-shoot cameras feature a built-in macro function, enabling you to get away with some pretty impressive minimum focusing distances without a dSLR or dedicated macro lens. Cool!

Macro lenses

While some lenses may not be able to focus on anything closer than 18 inches (or more) from the front of the lens, “macro” lenses allow you to get much closer to your subject, helping you capture extremely close up and detailed shots (as seen in Figure 5.8 and Figure 5.9) that simply wouldn’t be possible otherwise. With a much closer “minimum focusing distance,” macro lenses can open up a whole new photographic world.

Figure 5.8. Flowers are popular subjects for macro photography.

Figure 5.9. The small minimum focusing distance of a macro lens allows you to shoot from a very close range, rendering images not possible with other lenses.

Now that you understand focal length, your camera’s crop factor (if it has one), and maximum aperture, you’re set to give the salespeople a run for their money the next time you’re at the camera shop!

Point-and-shoot lenses

Those of you with point-and-shoot cameras thought you got off easy on this one, didn’t you? Just because your lenses are permanently attached doesn’t mean there aren’t a few things worth knowing. Focal length, zoom, and the ever-troublesome digital zoom are all important factors to know and understand when comparing one point-and-shoot camera to another.

Focal Length and Zoom

Just as on the interchangeable lenses made for dSLRs, the focal length on your built-in lens is measured in millimeters, but the scale is dramatically different. The built-in lens likely has a focal range with smaller numbers than you would expect to find on dSLR lenses. For example, the focal length of the lens on one of my point-and-shoot cameras is 6–22.5mm (which works out to a dSLR equivalent focal range of something like 28–105mm). Because of the difference in scale, you can’t compare the numbers at face value, but the principles still apply. Smaller numbers mean wider focal lengths, and larger numbers mean more telephoto focal lengths.

What you’re really looking for when it comes to the built-in lens on a point and shoot, is the range between the two numbers. The larger the range, the more pronounced your zooming capabilities will be. The shorthand way of communicating this is by assigning your camera an “x” zoom number.

If the lens can zoom from 5–25mm, it’s said to have 5x zoom. Or, as in my point and shoot’s case, 6–22.5mm is the equivalent of a 3x zoom. The higher the x value, the greater the zoom range.

Digital Zoom-Just Say No!

TV crime dramas would lead us to believe that digital zoom is the cat’s meow. Even my beloved “Law & Order SVU” makes me giggle when super-zoomed, pixelated security camera footage shot from 300 yards away (in the dark) is analyzed, cropped even closer, then suddenly—as if truly touched by magic—becomes crystal clear, revealing an identifiable birthmark behind the criminal’s left ear (cue the music).

Manufacturers have been known to make desperate attempts to seduce you with seemingly impressive features like “digital zoom.” Nothing more than glorified in-camera cropping, it’s actually one of the worst things you can do to your photos, as you’ll see in Chapter 9, “Death by Cropping: Don’t Shoot the Messenger.”

Also measured with an x number (3x, 5x, or more), digital zoom picks up where optical zoom (what your lens is inherently capable of) leaves off, allowing you to zoom further than nature intended. To give you an example, I captured Figure 5.10 by zooming the lens as far as optical zoom would let me go.

Figure 5.10. These Colorado mountains were captured at the furthest extent of my point and shoot’s optical zoom capabilities.

Figure 5.11 shows how much closer digital zoom allowed me to get. A pretty dramatic difference, isn’t it? The trouble is it’s actually quite misleading.

Figure 5.11. This shows the same scene captured by maxing out my digital zoom. That’s a pretty ginormous difference, wouldn’t you say? As you’ll see in Chapter 9, it’s not healthy for your photos to be enlarged this way.

If you look at the metadata (digital photo guts) for this image on the computer (after downloading and opening it with photo software), you can see proof that both images were actually captured at the same focal length. Digital zoom only makes it look like Figure 5.11 was photographed at a greater focal length. In reality, it’s just a digital enlargement of the optical image captured by the sensor. Unfortunately, the quality is not the same as if the image had been captured optically, instead of with digital zoom.

Thankfully, many point-and-shoot cameras have the option to turn off digital zoom to avoid accidentally employing it. If your camera is one of these, I highly recommend it as digital zoom can be a serious-quality buzz-kill (especially if you continue the bad habit of further cropping your photos in post-production).

Shopping for lenses

In addition to focal length, maximum aperture, and minimum focusing distance, lenses can vary by size, shape, weight, the material they’re made of (plastic or glass), advanced features such as “vibration reduction” (to help with stabilization), and even their ability to auto focus (not all lenses can, so don’t assume). As you can see in Figure 5.12, lenses can also vary in color!

Figure 5.12. Various lenses range in size, shape, color, capability, and price.

Of course, all these variables also mean lenses can range dramatically in price, starting anywhere from around $50 to well over $25,000 each. Generally speaking, the larger the maximum aperture value and the greater the focal length, the more expensive the lens tends to be.

When trying to figure out which lens is right for you, ask yourself the following questions:

• What kinds of things do you plan to photograph? Do you like to shoot portraits, or are you more of a landscape person?

• What kind of environment will you most likely be photographing in? Do you tend to shoot in bright, outdoor situations? Or are you more often in darker, low-light environments?

• Do you need a collection of specialty lenses with very wide apertures or maybe a macro lens? Or would a more general, multipurpose lens be a better fit?

• Do you always find yourself zooming in and wishing you could get even closer? Or do you prefer the look of images shot at wider focal lengths?

If you tend to do a lot of shooting when you travel, be sure to consider the impact that carrying around multiple lenses might have on your mobility. I’ve found that, in many cases, the more gear I take with me on personal trips, the less I end up shooting because carrying everything around is often a royal pain (you may have noticed that most of the travel photos seen in this book were captured with a compact point-and-shoot camera).

Striking a balance between having the right gear for the occasion while still feeling comfortable is often the key.

Chapter snapshot

![]()

Next time you’re looking for a lens (or considering a point-and-shoot camera with a lens built-in), keep these things in mind:

• Focal length: Measured in milimeters, focal length relates to how close-up or far away a scene appears when viewed through the lens. Big numbers make things look closer; smaller numbers make things appear farther away.

• Wide-angle lens: Any lens with a focal length approximately 24mm or wider.

• Telephoto lens: Any lens with a focal length roughly 85mm or greater.

• Standard lens: A lens with a focal length around 50mm.

• Prime lens: Any lens with a fixed focal length.

• Zoom lens: Any lens capable of a range of focal lengths.

• Minimum focal distance: The closest distance at which a lens can focus.

• Macro lens: A lens capable of focusing very closely on subjects.

• Maximum aperture value: This refers to the largest aperture setting the lens is capable of. It may be a fixed number, like f/2.8, or it may be a range like f/3.5–f/5.6, indicating that the maximum aperture varies, depending on the focal distance. For example, a lens may be able to open up to an aperture of f/3.5 when zoomed all the way out but might only get to f/5.6 when zoomed further in.

• Optical zoom: The inherent zooming capabilities of your lens.

• Digital zoom: Simply an enlargement of the image from your camera sensor; consider turning it off.