8

8

Shaping the Creative idea: Accessing the Reason Brainset

… from the wheel to the skyscraper, everything we are and everything we have comes from one attribute of man—the function of his reasoning mind.

—AYN RAND, THE FOUNTAINHEAD1

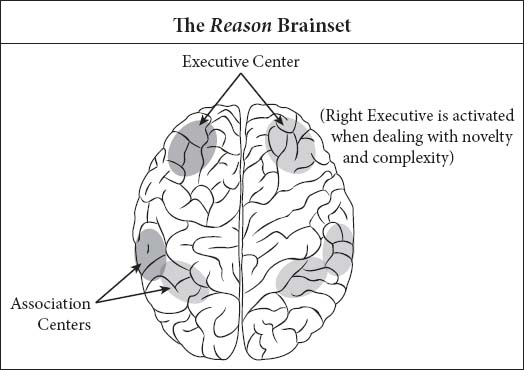

IF THE CONNECT BRAINSET is the activation pattern for divergent thinking, the reason brainset is the activation pattern for convergent thinking. In the reason brainset, your executive center in the prefrontal cortex solves convergent, logical problems, with all the resources of your stored memory, knowledge, and learned skills at its disposal. Thinking in the reason brainset is conscious, deliberate, and sequential. And regardless of whether you're arranging flowers in a new way, writing poetry, or developing a new rocket to put humans on Mars, you will have need of the brain activation pattern of the reason brainset as you complete your creative project.2

For many people, the reason brainset comprises their mental comfort zone. Here mental life is orderly and transparent, with no unpredictable surprises seeping or leaping in from the back rooms and subterranean regions of the unconscious. The reason brainset allows you to control what thoughts inhabit your mental workspace. If you don't like what you're thinking, you just banish the thoughts and go in another direction.

For other people, though (including many artists and musicians I have worked with), the reason brainset is foreign territory. A substantial number of artistic individuals spend much of their time in what I am calling the transform brainset, perilously riding waves of emotion and reacting to their environment rather than consciously acting to guide their mental ship (see Chapter Ten). If you fall within this category, please pay special attention to this chapter. You do not have to become Mr. Spock to take advantage of the benefits of the reason brainset. Your emotions will survive intact; they just won't be steering the ship.

Likewise, if the connect, absorb, or envision brainset is your mental comfort zone, you need to read this chapter carefully. You'll get some tips on how to engage in the logical, step-by-step thinking that will help you get past the idea-generation stage and into the action stage of making your creative dreams come true.

While the reason brainset is modeled as the seat of convergent thinking, your brain is not limited to thinking convergently when it is in the reason mode; it can also tackle ill-structured or open-ended problems. However, it does so by generating one possible solution at a time and using trial-and-error techniques rather than by the rapid generation of multiple solutions that we see in divergent thinking. The reason brainset is the principal activation mode for the deliberate pathway to creativity (discussed in Chapter Four). While we've heard about many highly creative people who prefer the insights and “ahas!” of the spontaneous pathway (accessed through the absorb brainset), there are probably an equal number of creative luminaries who have preferred the deliberate process.

Many innovators (certainly Thomas Edison and other inventors) prefer to work toward solutions using a logical trial-and-error method. Likewise, many composers, such as Bach, have used a logical approach to writing music, in which new compositions—I've already mentioned the Brandenburg Concertos—are developed by following explicit conventions. Art in the styles of Realism and Trompe l'Oeil is also generated primarily through the reason brainset.3

However, even if you prefer the spontaneous pathway to creativity, you will need to spend considerable time in the reason brainset as you revise, elaborate, and implement your creative ideas. One of the most controversial cases of reason improving on spontaneous insight is that of Samuel Taylor Coleridge's classic poem fragment Kubla Khan. According to the Coleridge, as he woke from an opium-induced sleep (opium was not illegal then and was prescribed for a variety of ills—apparently the Romantic poet was suffering from an anything-but-romantic bout of dysentery at this time), the vision of Kubla Khan came to him spontaneously. He experienced it simultaneously as both a visual image and a verbal description (which he subsequently wrote down) without any sensation of consciousness of effort.4 The essence of pure spontaneity!

David Brega's Colors (1999–2000) is an example of Trompe l'Oeil art that uses logic and information from the science of optics and perception to fool the eye into seeing a three-dimensional representation.

PHOTO CREDIT: Photograph by Rick Kyle/5000K Inc.

However, critics who don't believe in the spontaneous pathway (yes, there are such individuals even among creativity researchers) have pointed out that the published poem is quite different from the version written down by Coleridge after his so-called vision. Apparently, he did considerable rewriting and editing of the vision material. Why would anyone, the critics ask, mess with a vision?5 Isn't this evidence that there was, in fact, no spontaneous production? However, my response to such criticisms is this: A creative idea can arrive spontaneously and appear to be quite complete; that doesn't mean it can't be improved with a little reason brainset activity! Even my songwriter from Chapter Five, who claims she gets her songs from the angels, edits some aspects of the music. The point is that no matter how you come up with your original idea, if it is worth creating, then it's worth improving, reworking, and elaborating … and that all happens in the reason brainset.

Defining the Reason Brainset

The reason brainset is the brain state that you access when you engage in everyday problem solving. You use this state to plan your day (pick up the dry cleaning, attend the conference, pick up the dog from the groomers, stop for Chinese takeout, and so on). You also use it to make decisions (study for the bar exam tonight versus watch reruns of Lost; watch CNN versus watch Fox News), and to solve problems (what shall I serve for the dinner party on Saturday; how can I get little Britney to do her homework).

However, the reason brainset does more than perform these daily housekeeping functions. It is also the mental home of philosophers, mathematicians, and scientists who follow ideas to their logical conclusions. In other words, this brainset is active when you are consciously thinking things out, from the mundane to the earthshaking. It is the brain activation pattern you access when you are thinking intentional thoughts.

Before I continue, let me clarify what I mean by the words “reason,” “rational,” and “logical.” These terms are used more or less interchangeably in modern parlance, although they do have specific meanings in the field of philosophy. I will use them interchangeably as well. What I mean by “reason” is a type of thought in which you arrive at hypotheses and conclusions based on observations and knowledge that you believe (correctly or incorrectly) justify those conclusions. This can include both deductive and inductive reasoning. Reason also employs cause-and-effect thinking. Things don't just happen without pattern or purpose in a reasonable world. Reason assumes that every effect has a cause, even if the cause is unknowable at the present time. Therefore, much thought that is reasonable is an attempt to determine either causes or effects.

Let me give an example from the research of my friend and former office mate at Harvard, Susan Clancy. Clancy studied the memory patterns of individuals who believed they had been abducted by aliens from outer space. Many of these people, she found, were very reasonable. They held good jobs and had friends and secure family relationships. They were not, as a rule, psychotic. In her book Abducted: How People Come to Believe They Were Kidnapped by Aliens, Clancy states, “Alien-abduction beliefs reflect attempts to explain odd, unusual, and perplexing experiences.”6 In other words, abduction beliefs were an attempt to use reason to find the cause for unusual effects. These unusual effects included waking in the night with large-eyed strangers bending over their beds, being paralyzed and unable to move but still able to perceive, awakening in the morning to find strange marks and bruises on their bodies, strange compulsions to drive to remote spots out in the country, unexplained nosebleeds, and unexplained feelings of violation, terror, and helplessness. Just as a scientist collects data and fashions a hypothesis to explain the data, Clancy's subjects collected data in the form of unusual experiences and fashioned a hypothesis to explain them. Reason dictates that there is a cause for these effects, and the alien-abduction hypothesis fits the data. Reason doesn't always lead to truth. But, hey, the Truth is out there!

The reason brainset, then, reflects a type of thinking in which hypotheses and conclusions are formed on the basis of evidence (in the form of past experience or knowledge). Likewise, ideas, decisions, and plans for the future formed in the reason brainset are also based on evidence from your bank of past experience and knowledge.

Three factors define the reason brainset: conscious and intentional control of thought processes, realism or practicality, and sequential processing. Let's look at each factor separately.

Conscious Control of Thought Processes

Cogito ergo sum (I think therefore I am)

—RENE DESCARTES7

Descartes’ famous one-liner was originally written as evidence that we exist. Thought exists (it must because I am thinking, he reasoned). Thought cannot be separated from me, therefore, I exist. Pretty cool. Such thinking about thought is called metacognition. Conscious direction of thought is presumably a human characteristic (although see Irene Pepperberg's cognition work with Alex the grey parrot to change your mind about what it means to be a bird brain!).8 However, creativity is also a human characteristic and, as we've seen, one of the keys to entering brainsets often associated with creativity—including the absorb, the envision, and the connect brainsets—is the willingness to relinquish conscious cognitive control to allow ideas to enter consciousness uncensored (or at least only partially uncensored). What you are striving for is the ability to switch between brainsets that allow uncensored ideas into awareness and those in which you are actively controlling thought. (See Reason Exercise #1 for practice in controlling the flow of uncensored thoughts.)

Realism or Practicality

When you're in the reason brainset, you tend to think in realistic and practical terms. This state is not characterized by flights of fancy (note that Susan Clancy's alien subjects only settled on the alien abduction hypothesis after other more practical explanations failed to explain the data);9 rather, you look at things analytically. Your thoughts are pragmatic; you think in terms of what will or might work rather than how you would like things to work. This does not mean that you ignore fanciful or imaginative ideas. In fact, the reason brainset is the perfect place to take a fanciful idea to flesh it out and make it practical.

Remember the example of talking trash cans from Chapter Five? Well, I have no idea how the innovative folks at Solar Lifestyle came up with that idea, but once they had it, they were able to couch it in a sensible and realistic business plan that appears to have worked well for the people of Berlin. Solar-powered talking trash cans are now common in many cities throughout the world. Trash cans in Shanghai not only thank people for throwing their trash away, but they have built-in solar trash compactors for easy trash pickup (they also direct pedestrians to the nearest public restroom, although no one is sure what that has to do with trash disposal). Finnish trash cans sport voices of Finnish celebrities, and they even throw in some political commentary when passersby deposit their rubbish.10 Talking trash cans have the very practical outcome of keeping the city streets clean. This is just one example of how a fanciful idea—perhaps conceived in a different brainset—can be “practicalized” in the reason brainset.

One of the greatest examples of how an imaginative idea (originating in the envision brainset) can be elaborated by reason is the work of J.R.R. Tolkien. He invented the fantasy world of Middle Earth, which has captivated several generations of readers with tales of hobbits, fairies, elves, and wizards. Yet the details of Tolkien's fantasy world are so realistic as to astound his followers. He created entire languages for the species of his world, each with its own rules of syntax and grammar. He created detailed maps of his world, and his characters have observable and consistent (one would assume genetically endowed) temperamental characteristics.11 In short, the elaboration of Middle Earth and its inhabitants is incredibly realistic and practical, even though Middle Earth itself is a fantasy.

One of the practical functions of the reason brainset is problem solving. Although most people have figured out effective methods for solving problems on their own, other people—often highly creative individuals—seem to have difficulty solving problems in reasonable ways. One chef I interviewed related that he solved problems by throwing a temper tantrum. That works … for a little while. Although many people find anger very uncomfortable and will bend over backwards to assuage anger in others, they will eventually start avoiding the angry person, who will then be left—like my chef—wondering why their coworkers abandon them. A musician told me that she solves problems by bursting into tears; then either her husband or her manager will take care of things. Other people have told me their strategy for dealing with problems is to get drunk! These coping mechanisms are ultimately not practical. They either don't solve the problem or they throw your problems onto someone else. It's amazing how much more productive you'll be if you have a reasonable strategy for solving problems. (See Reason Exercise #2 to practice steps in practical problem solving.)

Sequential Processing

You think sequentially when you're in the reason brainset.12 That's because you can really only consciously focus your attention on one thing at a time. Okay, I know that it feels like you're focusing on three or four things at once sometimes. One of my best friends claims she can talk on her cell phone, paint her fingernails, and drive on I-95 at breakneck speed all at the same time. Brain research indicates that you can, in fact, have several motor programs running simultaneously (stepping on the accelerator, applying nail polish, and moving your mouth to talk), but you can only focus your conscious attention—your thought—on one thing. What feels like mental multitasking is really a sequential shift of attention back and forth among several streams of thought and action.13 (My friend with the nail polish shall remain nameless so as not to alert the state troopers.)

Not only does the conscious brain think sequentially, it plans sequentially. Being able to plan for the future is one of the great accomplishments of the executive center in your prefrontal cortex. Because time is experienced sequentially and appears to proceed in a straight line (at least until we are able to build a workable time machine), the executive center makes plans sequentially. Planning for the future is basically just setting goals, and the executive center of your brain sets hundreds of goals for you each day.14 When you wake up in the morning (something the executive does not have control over … unless it has directed you to set an alarm clock), the executive sets a goal that you will get out of the bed without falling over and make it to the bathroom to prepare for the day. Each willful act you perform is a goal accomplished, from brushing your teeth, to getting to work, to eating dinner. Of course, the executive can plan much loftier goals as well. Perhaps your executive is planning law school for you or planning for you to become a millionaire or to get through the year without smoking.

Goal setting is the act of making a sequential plan for the attainment of an action or state that is important to you. Goals are essential to creative work. However, again, if you are someone who is more comfortable in the absorb, envision, connect, or transform brainsets, you may not give much conscious thought to setting goals. Yet here are some of the things that goal setting can do to help you achieve your creative objectives:

- Motivate action

- Help you manage time

- Increase chances for success

- Increase self-confidence

- Increase sense of control over your life15

The trick is to have written and specific goals, and you achieve this in the reason brainset. (For practice in setting written and specific goals, see Reason Exercise #3.)

Neuroscience of the Reason Brainset

Exactly what does your brain look like when you access the reason brainset? The main finding is that the part of the brain we have dubbed the executive center and the circuits attached to it are highly active. This activation is especially apparent in the left hemisphere, because for all right-handed and many left-handed people, the language production center is located in the left frontal cortex. Even if you're not speaking out loud, this area is activated when you're thinking with words.16

While many people consider themselves visual thinkers, they are generally still using verbal thoughts in conjunction with visual thoughts. Therefore, the use of language and the use of the left hemisphere predominate when you are directing your thoughts consciously. However, your right executive center may be recruited if the information you're thinking about is quite complex.17

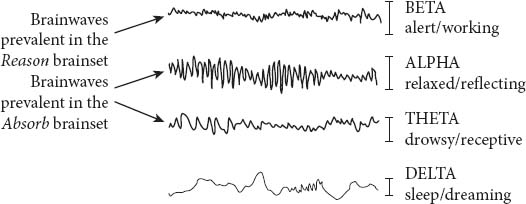

When people are solving problems in the brain scanner, the executive center and the left association areas light up. Conscious problem solving is also associated with increased high frequency/low amplitude beta wave activity in the prefrontal cortex and decreased alpha and theta wave activity. This pattern of brain waves indicates that the prefrontal cortex is more active during purposeful thinking than it is during rest. Note that while beta waves predominate during the reason brainset, it is the slower waves that characterize the absorb brainset. Again, this may be indicative of the prefrontal brain activation and deactivation that accompany these brainsets.18

Finally, the reason brainset is an active brainset (as opposed to a resting brain activation pattern). Therefore, it requires a certain level of physiological and mental arousal. There is an increase in the so-called arousal neurotransmitters, including glutamate, dopamine, and norepinephrine. There are a number of methods you can use to effect this arousal. The most effective and important is moderate physical exercise. Taking a walk will reliably activate the frontal lobes of your brain.19

What else? We mentioned caffeine in the last chapter. That works … but watch out for the dose-dependent “jitters.” And what about classical music—the so-called “Mozart Effect”? Well, it looks like Mozart may be good for waking up your brain and putting you in a better mood—if you like Mozart. Does it make you reason better? A study by Edward Roth and Kenneth Smith of Western Michigan University found that listening to Mozart significantly increased scores on a portion of the standardized GRE exam; but so did listening to traffic sounds. Basically, any noise will increase your arousal level, which in turn increases the activation of the prefrontal lobes and your executive center.20 So if your favorite nonvocal music doesn't distract you too much, it may be helpful in getting you into the reason brainset. (For other methods of accessing the reason brainset, try Reason Exercises #4 and #5.)

Freud, Reason, and Neuroscience

Because Freud's theories figured prominently in early twentieth-century thinking about creativity, I want to bring him into our discussion here. I was taught in grad school that “serious” cognitive scientists didn't discuss Freud (concepts like “the unconscious” were considered untestable and therefore unscientific). He has, however, regained some respect among scientists as we are finding out more about the mental processes that occur below the level of conscious awareness (yes, there is an unconscious aspect to brain function, and, as suggested by Freud, that is where a lot of the action is going on!). I will no doubt be criticized by both Freudians (who will feel I'm oversimplifying extremely complex psychoanalytic material) and by brain researchers (who will say I am conflating questionable theory with actual neuroscience findings). However, I see Freud's thinking as a precursor to some of the ideas we've been discussing, so with apologies all around, here goes:

Freud's ideas of “primary process” and “secondary process” thinking were quite descriptive of what neuroscientists now refer to as the spontaneous and deliberate pathways. According to Freud, secondary-process thinking includes rational, sequential, and realistic thinking that is actively controlled by the ego (the reality-based conscious part of the personality). Secondary-process thinking is precisely the type of thinking that occurs in the reason brainset. This is in stark contrast to primary-process thinking, which is primitive, irrational, nonsequential, unrealistic, imaginative, and controlled by the id (the fantasy-based unconscious part of the personality that strives for self-gratification).21

Primary-process thinking, according to Freud, is evident in very young children, whose brains and ego defenses have not developed sufficiently to allow secondary-process rational thinking. After the full development of the ego, primary process can be accessed only through dreams, drug-induced mental states, psychotic episodes, and high fevers. For the most part, the mature ego is protected from primary-process material; however, every once in a while, primary-process content makes an end run around the ego defenses and careens into conscious awareness.

This sounds very much like a bolt of insight from the spontaneous pathway to creativity, doesn't it? In fact, Ernst Kris, in his 1952 book Psychoanalytic Explorations of Art, suggested that creative individuals are prone to primary process thinking that explodes into consciousness. He believed that creative individuals have the ability to switch between secondary-process and primary-process thinking more easily than their less creative counterparts; he called this switching into primary process “regression in the service of the ego.” The “regression” process involves two parts: (a) the ego withdraws its control and allows the psyche to slip into the more childlike and imaginative state of primary-process thinking where material wells up from the unconscious (this corresponds to the “insight” stage of the creative process), and (b) the ego resumes control and works with material generated in the primary process (this corresponds to the “verification” stage of the creative process; see Chapter Four).22

Regression in the service of the ego approximates the process that Coleridge went through with the Kubla Khan fragment. And, in fact, it also approximates what neuroscientist Arne Dietrich of the American University in Beirut believes actually happens in the brain during insight and verification: the executive centers in the prefrontal cortex momentarily and purposely deactivate to allow material to feed forward from TOP association areas into conscious awareness. (Dietrich refers to this as the Transient Hypofrontality Hypothesis.) The prefrontal lobes then reactivate to work with this new material.23

Thus Freud, long criticized by scientists for his decidedly non-scientific, non-verifiable theories, may prove to have been prescient in his explanation of brain mechanisms. Indeed, a whole branch of Freudian psychology, called neuro-psychoanalysis, is devoted to mapping Freud's theories onto current knowledge of brain functioning.24

When to Access the Reason Brainset

Although the other brainsets that we've looked at so far (absorb, envision, and connect) get billing for being the “creative” brain activation patterns, the truth is that the reason brainset is, as Ayn Rand put it at the beginning of this chapter, where “everything we have comes from.” Our ability to reason, to plan, and to make decisions directs any creative efforts in which we may engage.

By careful observation of your environment, you can determine practical new areas that are ripe for change. This will help you find problems that can benefit from creative input.

Next, the reason brainset is crucial in the deliberate pathway to creativity. You can come up with creative ideas through reason, and through trial and error. Sometimes taking your creative problem and “thinking it through” will yield an original and useful solution.

Think about the creative act of writing a paper for your business or telling others about your work. Both writing and speech involve creativity as you choose how to arrange the words in an orderly progression. Although the idea you talk or write about may be inspired, your grammar and syntax are organized by the reason brainset. Others couldn't understand what you're saying if it weren't for this organization.

Once you have obtained a creative idea, you will find that you need the reason brainset to decide what to do with it. If the idea passes the muster of evaluation, then you will need to revise and elaborate it. You will need to implement it in some way so that it can be available to others. All of this will take your best reason brainset thinking.

The take-home message of this chapter (and one of the main points of this book) is that, however creative inspiration occurs, whether through the spontaneous or the deliberate pathway, the reason brainset, and its reliance on the executive center in the prefrontal brain, is a necessary and vital participant in converting an original thought into a creative accomplishment that can benefit yourself and others.

But we get ahead of ourselves—before you put the time and effort into elaborating and implementing your ideas, you need to check them for worthiness. Judging your ideas is the province of the evaluate brainset, and that is a different state of mind altogether. In the next chapter, you'll learn how to enter a brainset that is helpful for evaluating your work. You'll also learn how to handle evaluation and criticism of your work from others.

Exercises: The Reason Brainset

Reason Exercise #1: Conscious Control of Thought: Thought-Stopping25

Aim of exercise: To improve your ability to direct your thoughts consciously and help you stop unwanted thoughts that interfere with your ability to think logically. This technique, called “thought-stopping” is a behavioral tool used in clinical psychology to help patients control their angry or anxious thoughts. You will need a three-by-five index card and a writing utensil. It will take you about five minutes to prepare your thought-stopping card. You can practice using it whenever unwanted thoughts enter your mind. Try to do this for the next two weeks.

Procedure: In this approach, you will simply tell yourself to stop particular thoughts as soon as you notice them. You can do this through a set of verbal self-commands or through mental images that direct you to stop paying attention to thoughts that are upsetting or distracting. Let's look first at some verbal commands you might give yourself to stop negative or distracting thoughts.

“I need to stop thinking these thoughts.”

“Don't buy into these thoughts.”

“Don't go there.”

“Stop this thought now!”

“Mentally walk away.”

“Don't buy into this thought.”

“These thoughts won't help the situation.”

“I need to stop thinking these thoughts.”

- Imagine saying each of these commands to yourself when you're having thoughts you don't like. Select at least four that you think would be effective for you and write them on one side of your index card.

- Now take a minute to write down at least two other commands you could give yourself that would help you stop thinking negative thoughts. Write these below the commands you've already chosen. You should now have at least six mental commands you can use if negative or otherwise unwanted thoughts enter your mental workspace.

Some people prefer to use visual rather than verbal commands to stop unwanted thoughts. These could include visualizing:

A stop sign

A red stop light

A hand raised in the Stop position

The words “negative thought” with an X through them or with a superimposed international “no” sign (a circle with a diagonal slash)

An arrow directing you to a calming vision such as a waterfall

A person listening to soothing music through headphones

- Imagine visualizing each of these image commands when you're having thoughts you don't like. Select at least three that you think would be effective for you and write them on the opposite side of your index card.

- Take a minute to write down at least two other things you could visualize that would help you stop negative thoughts in their tracks. Perhaps an image of the bad thought scrolling across the screen of your mind and breaking up into tiny crystals and falling out of sight.

- Each time an unwanted thought pops back into your mind, use a thought-stopping command or visual, and keep doing this until the negative thought runs out of steam. This could take as long as fifteen minutes or so. But be persistent: Refuse to let the negative thoughts regain control of your attention.

If you are using the token economy incentive, give yourself one reason token for creating the thought-stopping card and one token each time you use the technique successfully.

Reason Exercise #2: Steps in the Problem-Solving Process26

This process is straightforward and produces results. The more you practice problem solving, the more easily you will be able to apply this skill to both your personal and your creative problems. The following problem-solving process is adapted from work I did with the afterdeployment.org project. If you have trouble meeting your problems head-on—and especially if your mental comfort zone is in the envision, connect, or transform brainset—you should find this process quite helpful.

Step 1: Recognize when you have a problem. One of the clearest signs that you have a problem is the presence of negative emotions. When you feel stressed, anxious, ashamed, or depressed, it may signal that a problem needs to be addressed.

Step 2: Define the problem. Decide what the problem actually is and be very specific about what has caused (or is causing) it.

Step 3: Set a goal. Set a very specific goal for dealing with the problem. Make sure that this goal is something that is within your power to achieve.

Step 4: Brainstorm possible solutions. Use a little connect brainset and brainstorm possible solutions to the problem that will satisfy the goal you have set. Open your mind and get really creative about possible solutions. When you brainstorm, do not judge any of the solutions you come up with, just let them flow. Even if some of your ideas seem ridiculous, write them down without judging them.

Step 5: Evaluate possible solutions. Use a little evaluate brainset and make a list of the pros and cons for each of the possible solutions from Step 4.

Step 6: Choose the best solution based on pros and cons. Once you have looked at the pros and cons of all reasonable solutions, choose the best one. (Note: Problem-solving experts suggest giving special consideration to the solution with the least cons rather than the solution with the most pros.)

Step 7: Make a plan to implement the solution and try it! You now need to create a specific plan to implement your solution. You may need to divide the plan into steps. Set a deadline for the completion of each step. (See more about this under Reason Exercise #3: Steps in Achieving Your Goals.)

Step 8: Assess success. After giving your solution a fair try, the next step is to decide if your solution worked. Did you meet the goal you set in Step 3?

Step 9: If the first solution didn't work, try another! If your solution worked, your negative feelings should be diminished. If it did not work, you can always try the second and then the third solution from Step 5 until you find one that will work for you. Make sure to create a specific plan and give it adequate time to work!

Problem solving is a skill. And, like all skills, it needs to be practiced before it becomes mastered. Practice meeting your problems face-to-face and using this process. You will soon become a master at coming up with reasonable and practical solutions.

If you're using the token economy incentive, award yourself five reason tokens each time you solve a problem using the Steps in the Problem-Solving Process. (Note that the reward for this exercise is large because problem solving is such an important skill not only for creativity but also for all aspects of your life.)

Reason Exercise #3: Steps to Achieving Your Goals27

Step One: Write down a creative goal that is important to you.

- Give your goal some thought. Imagine what you'd like your life to look like five or six years from now. What would you like to have accomplished?

- Make your goal a positive statement rather than a negative statement.

- Make sure that your goal reflects your desires, not the wishes of someone close to you and not what you think society would expect you to do. In order to achieve its full effectiveness, your goal has to come from within.

- Make your goal as specific as possible.

- Make sure your goal is challenging but at the same time realistic. If your goal is too difficult, you'll feel anxious and frustrated. If it's too easy, you'll become bored and lose motivation. You want your goal to be a stretch but not impossible.

Example: Lorne is a talented sculptor. Years ago he had drawn a series of sketches that he thought would make great bronze garden sculptures, but he kept putting off doing anything about them. When he lost his job as a graphic designer due to downsizing, he decided to get busy on his old idea. He wrote his goal as follows:

“My goal is to produce and sell at least three of my garden sculptures within the next two years.” (Notice how his goal is positive, specific, and reasonable.)

Step Two: Create a plan for the attainment of your goal.

- First, write down all the intermediate steps, called mini-goals, that you will need to accomplish in order to make your main goal a reality. This may take some research.

- Once you have a list of mini-goals or steps toward your main goal, put them in chronological order. What sequence do you need to follow to arrive at the big goal?

Example: Lorne's mini-goals included: making models of each sculpture from his sketches, molding a cast for each, locating a foundry that could cast his statues with sufficient detail, having the pieces cast, and selling the sculptures.

- Next you need to get really specific. Again, this part of the step may take some research. Make a list of everything you need to do to accomplish each of your mini-goals.

- Then set up a timetable for the completion of each step in your first mini-goal. You may want to use a spreadsheet for this work.

Example: This is Lorne's timetable for one of his mini-goals:

- As you near the completion of your first mini-goal, you can work on setting up a timetable for the completion of the steps in the second mini-goal.

- Be sure to schedule in time for contingencies and setbacks. If you plan for snags ahead of time, they will not be so upsetting when they inevitably occur.

Step Three: Implement your plan.

- Begin as soon as possible, but pace yourself. Many people start off working toward their goals with a flurry of activity and at a pace that they can't maintain. Try to march slowly and steadily toward your goal.

- Schedule the time into your calendar on a regular basis to make sure the journey toward your goal remains a priority. Also, if an unforeseen obstacle crops up, you can go back and change the target dates on your goal plan. Don't let an obstacle squash the entire plan!

- Write down your goal and post it where you can review it daily. Each morning when you wake up, look at your goal and visualize it as though you had already completed it. Then each night, right before you go to bed, look at it again. Each time you make a decision during the day, ask yourself, “Will this take me closer to or further from my goal?”

- Reward yourself when you reach each of your mini-goals. And when you complete your goal, give yourself some time to savor your accomplishment, then set another challenging goal.

If you're using the token economy incentive, reward yourself with five reason tokens for writing out each of your creative goals and setting a timetable for its achievement.

Reason Exercise #4: Executive Center Activation: Memorization

Aim of exercise: To improve your ability to activate the prefrontal circuits associated with the executive center. (Note that the subcortical areas associated with learning—such as the hippocampus—are also activated with this exercise.) You will need copies of 10 poems that you enjoy and that you do not know by heart. Sources may include a book of poetry or the Internet. Copy the poems so that you have printed or handwritten paper copies to refer to. This exercise is variable in time commitment.

Procedure: As access to electronic information becomes more and more available (through computers and now Smartphones), the need to memorize material has decreased. However, memorization is an effective tool for activating brain circuits associated with learning and executive functions.

- First, make a stack of your poems in order of their length, with the shortest poem on top. This is your “poem of the week.”

- Memorize the poem over the course of one or two days. If you have chosen a poem of considerable length (for example, the “Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam,” which has some 100 verses), you may need to delegate more days to its memorization.

- Once memorized, recite your poem to yourself each day for seven days.

- Continue to learn and recite one of your poems each week for 10 weeks.

The acts of learning and memory retrieval will strengthen your cognitive skills and also get you into the reason brainset. In addition, you will have committed to heart work that inspires or moves you, which can in turn influence your own creative work.

If you are using the token economy incentive, give yourself two reason tokens for each poem you learn and recite for one week.

Reason Exercise #5: Executive Center Activation: Become an Expert

Aim of exercise: To improve your ability to activate the prefrontal circuits associated with the executive center. (Note that the subcortical areas associated with learning—such as the hippocampus—are also activated with this exercise.) You will need Internet access and a variable block of free time.

Procedure: Pick a topic that you know nothing about or would like to know more about. This should be a relatively restricted topic that you can get a grasp of without researching for a dissertation. Here are some topics chosen by others: tree-climbing lions, the life of Beethoven, the “lost wax” process, North American wildflowers, cell phone radiation.

- Use both Internet sources and scholarly sources to learn about this topic. However, be careful to stay on topic. If you start to get distracted by another topic while you're doing your research, make a note of it and return to your chosen topic.

- Take notes and make a computer file on your topic. Be thorough. You don't want all your information from one source. Your investigation should include a number of sources.

- Choose a new topic every two months.

- Keep an eye out for new developments in your chosen topic areas and periodically update and review your topics of expertise.

This exercise is fun to do with another person with whom you can share your acquired knowledge. Not only does this exercise activate the reason brainset, but it will increase your intellectual curiosity. Your newfound expertise will also make you a more interesting person and may also suggest areas for potential creative development. If you are using the token economy incentive, give yourself three reason tokens for each topic you research.